Merit (Buddhism)

Merit (Sanskrit: puṇya, Pali: puñña) is a concept considered fundamental to Buddhist ethics. It is a beneficial and protective force which accumulates as a result of good deeds, acts, or thoughts. Merit-making is important to Buddhist practice: merit brings good and agreeable results, determines the quality of the next life and contributes to a person's growth towards enlightenment. In addition, merit is also shared with a deceased loved one, in order to help the deceased in their new existence. Despite modernization, merit-making remains essential in traditional Buddhist countries and has had a significant impact on the rural economies in these countries.

Merit is connected with the notions of purity and goodness. Before Buddhism, merit was used with regard to ancestor worship, but in Buddhism it gained a more general ethical meaning. Merit is a force that results from good deeds done; it is capable of attracting good circumstances in a person's life, as well as improving the person's mind and inner well-being. Moreover, it affects the next lives to come, as well as the destination a person is reborn. The opposite of merit is demerit (papa), and it is believed that merit is able to weaken demerit. Indeed, merit has even been connected to the path to Nirvana itself, but many scholars say that this refers only to some types of merit.

Merit can be gained in a number of ways, such as giving, virtue and mental development. In addition, there are many forms of merit-making described in ancient Buddhist texts. A similar concept of kusala (Sanskrit: kusala) is also known, which is different from merit in some details. The most fruitful form of merit-making is those good deeds done with regard to the Triple Gem, that is, the Buddha, his teachings, the Dhamma (Sanskrit: Dharma), and the Sangha. In Buddhist societies, a great variety of practices involving merit-making has grown throughout the centuries, sometimes involving great self-sacrifice. Merit has become part of rituals, daily and weekly practice, and festivals. In addition, there is a widespread custom of transferring merit to one's deceased relatives, of which the origin is still a matter of scholarly debate. Merit has been that important in Buddhist societies, that kingship was often legitimated through it, and still is.

In modern society, merit-making has been criticized as materialist, but merit-making is still ubiquitous in many societies. Examples of the impact of beliefs about merit-making can be seen in the Phu Mi Bun rebellions which took place in the last centuries, as well as in the revival of certain forms of merit-making, such as the much discussed merit release.

Definition

| Translations of Merit | |

|---|---|

| Sanskrit | puṇya |

| Pali | puñña |

| Burmese | ကောင်းမှု (MLCTS: káʊ̃ m̥ṵ) |

| Chinese | 功德 (Pinyin: gōng dé) |

| Japanese | くどく (Rōmaji: kudoku) |

| Lao | ບຸນ (bun) |

| Tibetan | བསོད་ནམས (bsod nams) |

| Thai | บุญ [būn] (RTGS: bun) |

| Vietnamese | công đức |

| Glossary of Buddhism | |

Puñña literally translates as 'merit, meritorious action, virtue'.[2] It is glossed by the Theravāda Commentator Dhammapāla as "santanaṃ punāti visodheti", meaning 'it cleans or purifies the life-continuity'.[3][4] Its opposites are apuñña (demerit) or pāpa ('infertile, barren, harmful, bringing ill fortune'),[2][4][5] of which the term pāpa has become most common.[3] The term merit, originally a Judeo-Christian term, has in the latter part of the twentieth century gradually been used as a translation of the Buddhist term puṇya or puñña.[6] The Buddhist term has, however, more of an impermanent character than the English translation implies,[7] and the Buddhist term does not imply a sense of deserving.[8][9]

Before the arising of Buddhism, merit was commonly used in the context of Brahmanical sacrifice, and it was believed that merit accrued through such sacrifice would bring the devotee to an eternal heaven of the 'fathers' (Sanskrit: pitṛ, pitara).[10][11][12] Later, in the period of the Upanishads, a concept of rebirth was established and it was believed that life in heaven was determined by the merit accumulated in previous lives,[13][11][12] but the focus on the pitṛ did not really change.[10] In Buddhism, the idea of an eternal heaven was rejected, but it was believed that merit could help achieve a rebirth in a temporary heaven.[11] Merit was no longer merely a product of ritual, but was invested with an ethical meaning and role.[14][15]

In the Tipiṭaka (Sanskrit: Tripitaka; the Buddhist scriptures), the importance of merit is often stressed. Merit is generally considered fundamental to Buddhist ethics, in nearly all Buddhist traditions.[5][16][17] Merit-making is very important to Buddhist practice in Buddhist societies.[18][19][20]

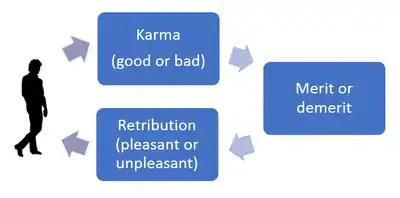

Merit is a "beneficial and protective force which extends over a long period of time" (B.J. Terwiel)—and is the effect of good deeds (Pali: kamma, Sanskrit: karma) done through physical action, words, or thought.[21][22][23] As its Pāli language (the language of Theravada Buddhism, as practiced in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Myanmar, etc.) definition indicates, this force is associated with goodness and purity of mind.[24] In traditional Buddhist societies, it is believed that merit is more sustainable than that of magical rites, spirit worship or worldly power.[25] The way merit works, is that acts of merit bring good and agreeable results, whereas demeritorious acts bring bad and disagreeable results. A mixture of the two generates mixed results in a person's life. This karmic correspondence (Pali: kamma-sarikkhatā) or "automatic cosmic reaction" (Brokaw) is a common idea found in Buddhist texts and Buddhist societies,[19][26] and explains why people are different and lead different lives in many ways.[18][27] Karma is self-regulatory and natural: it operates without divine intervention and human intention is fundamental to it.[8][6][28] Internally, merit makes the mind happy and virtuous.[29][30][31] Externally, present good circumstances, such as a long life, health and wealth, as well as the character and abilities someone is born with, arise from merits done in the past and vice versa, with demerits.[21][32][33] The merits and demerits a person has done may take a while to bear fruit.[34] Merit or demerit may cause a good or bad future respectively, including in the next lives to come.[6][32] A bad destination after rebirth may be caused by demerit, but merely a lack of merit may also lead a person to be born in an unhappy destination.[35] When someone is reborn in a happy destination, however, one can only stay there as long as merits last.[36] Thus, it is stated in the Tipiṭaka that people cannot take anything with them when they die, except for whatever merit and demerit they have done, which will affect their future.[37][38][39] Merit can be accumulated in different quantities, and stored up, but also has an impermanent character: it can run out.[22][40][41] Summarizing from the Buddhist text Milinda Pañhā, some scholars conclude that merit is inherently stronger than demerit.[42][43] Moreover, many merits together have the power to prevent demerits from having an effect, by pushing them "to the back of the queue" (Richard Gombrich), though demerits can never be undone.[44][45][46]

All these benefits of merit (Pali: ānisaṁsa; Sanskrit: ānuśaṁsa), whether internal or external, are the aim in merit-making, and are often subject of Dharma teachings and texts.[47][48] Thus, merit is the foundation of heavenly bliss in the future,[2] and in some countries merit was also considered to contribute to the good fortune of the country.[49][50] Because merit is understood to have these many beneficial effects, it is sometimes compared with cool water, which is poured or which is bathed in. This symbol is used in merit transfer ceremonies, for example.[51][52]

Discussion in traditional texts

General

Merit is not only a concept, but also a way of living.[53] The Pāli canon identifies three bases of merit (puññakiriyā-vatthu),[2][38][39] in order of difficulty:[54][note 1]

- giving (dāna-maya)

- virtue (sīla-maya)

- mental development (bhāvanā-maya)

In Buddhist texts and practice, giving is considered the easiest of the three bases of merit.[56] It helps to overcome selfishness and stills the mind; it prepares the mind for the practice of virtue.[17] It is also considered a form of saving, considering there is a rebirth in which people receive back what they have given.[57] As for virtue, this comprises three out of eight aspects of the Noble Eightfold Path, the path central in the Buddhist teaching: right speech, right action and right livelihood. Being the main criterion for moral behavior in Buddhism, virtue is mostly about the undertaking of five precepts,[17][58] although the eight precepts may be kept now and then.[59] The five precepts are part of many Buddhist ceremonies, and are also considered a merit itself, helping the practitioner to become strong and healthy.[17][60][61] The benefits of practicing the three bases of merits are also summarized as three forms of happiness (Pali: sampatti)—happiness as a human being, happiness in heaven, and happiness in Nirvana.[62] When people die, what world they will be reborn into depends on how intense they practice these three bases of merit. It is, however, only mental development that can take someone to the highest heavenly worlds, or to Nirvana.[63]

Post-canonical texts and commentaries[note 2] such as the Dhammasaṅganī and Atthasālinī,[64][65] elaborating on the three bases of merit, state that lay devotees can make merit by performing ten deeds. Seven items are then added to the previous three:

- Giving (Dāna-maya)

- Virtue (Sīla-maya)

- Mental development (Bhāvanā-maya)

- Honoring others (Apacāyana-maya)

- Offering service (Veyyāvaca-maya)

- Dedicating (or transferring) merit to others (Pāli:Pattidāna-maya; Sanskrit: puṇyapariṇāmanā)

- Rejoicing in others' merit (Pattānumodanā-maya)

- Listening to Buddha's Teachings (Dhammassavana-maya)

- Instructing others in the Buddha's Teachings (Dhammadesanā-maya)

- Straightening one's own views in accordance with the Buddha's Teachings (Diṭṭhujukamma)[2][64][66]

These ten, the Commentator Buddhaghosa says, all fit within the three first bases of merit: 'Giving' includes 'Transferring merit to others' and 'Rejoicing in others' merit' by extension, whereas 'Virtue' includes 'Honoring others' and 'Offering service'. The remaining items 'Listening to Teachings', 'Instructing others in the Teachings' and 'Straightening one's own views' are part of 'Mental development'.[64] Thus, in Theravāda Buddhism, merit is always accrued through morally (good) actions. Such good deeds are also highly valued in the other two Buddhist schools, that is Mahāyāna (China, Japan, etc.) and Vajrayāna (Tibet, Nepal, etc.). In some forms of Mahāyāna or Vajrayāna it is believed, however, that even more merit will accrue from certain ritual actions, sometimes called the 'power of blessed substances' (Standard Tibetan: rdzas). These are considered an addition to the traditional list and can help protect against calamities or other negative events caused by bad karma.[16][67]

A number of scholars have criticized the concepts of merit and karma as amoral, egoist and calculative, citing its quantitative nature and emphasis on personal benefits in observing morality.[47][68][69] Other scholars have pointed out that in Buddhist ethics egoism and altruism may not be as strictly separated as in western thought, personal benefit and that of the other becoming one as the practitioner progresses on the spiritual path.[70][71][72] Buddhist ethics is informed by Buddhist metaphysics, notably, the not-self doctrine, and therefore some western ethical concepts may not apply.[72] Besides, as Keown notices, moral action would not be possible if it was not preceded by moral concern for others, as is illustrated by the example of the Buddha himself. Such moral concern is also part of the Buddhist path, cultivated through loving-kindness and the other sublime attitudes (Pali: brahamavihāra).[73]

Accumulation and fruition

In post-canonical and vernacular Pāli literature, such as the Jātaka stories of the Buddha's previous lives, the Avadānas and Anisaṃsa texts, as well as in many Mahāyāna texts, merit is the main concept. It is regarded as something which can be accumulated throughout different lifetimes in the process of attaining Buddhahood, and is also instrumental in attaining it. The Bodhisatta intent on accomplishing Buddhahood and bringing other beings across the ocean of suffering, must do so by accumulating all sorts of merits, in this context also called perfections (Pali: pāramī; Sanskrit: pāramitā). This form of merit-making is always led by a vow for enlightenment (Pali: panidhāna; Sanskrit: praṇidhāna), and an intention to enlighten others as well, as well as the transferring of merits to all living beings to that effect.[74][75][76] Another aspect of meritorious acts, emphasized more in later literature, is the idea that a single meritorious act done will reap many fruits, as, for example, expressed in the Vimānavatthu. Not only is the quality of people's next rebirth affected by their merits, but also the circumstances in which they are reborn; not only in the next life, but also in adjacent lives after that. Wealth, lifespan, and position are all contingent on merit.[32][33]

In Buddhist texts further details are given in what way and to what extent a meritorious deed will bring results: this depends on the spiritual quality of the recipient, the spiritual attitude of the giver, the manner in which one gives and the object given.[77][43][66] If the recipient is a human, the gift yields more fruits than if the recipient is an animal, but a gift to a sāmaṇera (a young monk), a monk, many monks, and the Buddha yield even more fruits, in ascending order.[78][79] If the giver is motivated by greed or other defilements of the mind, the merit gained will be much less than if the giver is motivated by loving-kindness or other noble intentions.[80] Even the intention of going to heaven, though in itself not considered wrong, is not seen as lofty as the intention to want to develop and purify the mind. If the recipient is spiritually "not worthy of the gift", the gift will still be meritorious provided the giver's intention is good, and this is also valid the other way around.[81][82] Good thoughts must also be maintained after the good deed is done, as regretting the gift will also decrease the merit.[83] Whether the giver pronounces a certain wish or intention also affects the meritorious deed, as the power of the merits can be channeled toward a certain purpose.[84][85][86][note 3] The manner in which people give is also important: whether someone gives respectfully or not, and whether by giving someone is harming anyone. With regard to the size of the gift, a larger gift is usually more meritorious than a smaller one, but purity of mind affects merit more than the gift's size.[87] It is therefore recommended to give as much as you can afford, no more and no less.[88] Such care in choosing whom to give to and how to give, is called being 'skilled in merit' (Pali: puññassa kovidā).[89]

Puñña, kusala and Nirvana

A teaching that exists in both Mahāyāna sūtras and Theravādin suttas is the teaching on the Ten Wholesome Ways of Action (Pali: kusaladhamma). In Mahāyāna, this teaching is described as the way in which a Bodhisattva prevents "suffering in all evil destinies". These ten wholesome ways are:

- In giving up the taking of life, the practitioner will accomplish freedom from vexations;

- In giving up stealing, the practitioner will find security in life, economically, socially and spiritually;

- In giving up wrongful (sexual) conduct, the practitioner will find inner peace and peace in the family life;

- In giving up lying, the practitioner will attain purity of speech and mind;

- In giving up slander, the practitioner will be protected socially and spiritually;

- In giving up harsh language, the practitioner's words will be more effective;

- In giving up frivolous speech, the practitioner will become wise and dignified;

- In giving up lust, the practitioner finds freedom in life through contentment and simplicity;

- In giving up hatred, the practitioner will develop kindness and gentleness;

- In giving up wrong views, the practitioner will not falter in the good and spiritual path.[90][91]

These ten actions are described as akusala ('unwholesome'; Sanskrit: akuśala), and when abstaining from them it is called kusala ('wholesome'; Sanskrit: kuśala).[92][note 4] Moreover, kusala and akusala are depicted as having 'roots' (mūla). Akusalamūla are the roots of evil in the mind (the defilements), whereas the kusalamūla are roots connected with good qualities of the mind. Both of them are called roots because they are qualities that can be cultivated and grown in the mind.[94][95]

Puñña and pāpa are close in meaning to kusala and akusala. Both pairs are used for distinguishing between ethically right and wrong. However, even though the negatives akusala and pāpa have almost the same meaning, there are some differences between the positives, kusala and puñña. According to P. D. Premasiri, Kusala is used to describe a more direct path to Nirvana than puñña.[96][97] Damien Keown, however, believes they are merely different angles of the same concept: kusala refers to the moral status of an action, whereas puñña refers to the experience of the consequences of the action.[98] He further points out that in the Pāli suttas (discourses) mental development (bhāvanā) practices such as meditation are also included in the path of merit. It is unlikely that in the Tipiṭaka meditation would be regarded as an indirect path or obstacle to Nirvana,[99][100] and there are passages that directly relate merit to Nirvana.[101][102] Sometimes a distinction is made between worldly (Pali: lokīya) and transcendental (Pali: lokuttara) merit, in which only transcendental merit leads to liberation.[103][104] The Thai scholar and monastic Phra Payutto believes that merit and kusala are both used to describe the 'cleanliness of the mind' (RTGS: khwam sa-at mot chot). But whereas merit aims for the 'beautiful and praiseworthy' (RTGS: suai-ngam na chuenchom) aspect of such cleanliness, with worldly benefits such as wealth, praise and happiness; kusala aims for the 'purity' (RTGS: borisut) aspect of cleanliness, with enlightenment as its benefit. Phra Payutto does add that both need to be accumulated on the Buddhist path. In making this comparison, he says this only holds for worldly merit, not for transcendental merit. Collins equates transcendental merit with kusala.[105][106] In the earlier Pāli texts, kusala was much more commonly used than puñña, puñña mostly being used in the context of the practice of giving.[107]

In a widely quoted theory, Melford Spiro and Winston King have distinguished two forms of Buddhism found in traditional Buddhist societies, "kammatic Buddhism" focused on activities such as merit-making, and "nibbanic Buddhism" which focuses on the liberation from suffering and rebirth.[108] In this theory, called the "transcendency thesis" (Keown), Buddhism has two quite separate aims, which are pursued by separate groups, that is, laypeople (kammatic) and monks (nibbanic). This view has, however, been downplayed or criticized by many other scholars, who believe that kammatic practices are in many ways connected to nibbanic practices, and the aims of monks and laypeople cannot be that easily separated.[109][110][111]

This transcendency thesis has also been applied to scriptural interpretation. When discussing the path to the attainment of Nirvana, in some passages in the Tipiṭaka merit is rejected. For example, in the Padhāna Sutta, the Bodhisatta (the Buddha Gotama to be) is tempted by Māra to give up his self-torture practices to do meritorious acts instead. The Bodhisatta replies that even a bit of merit is no use to him (Pali: "anumattenāpi puññena attho mayhaṃ na vijjati"). Some scholars, supporting the transcendency thesis, have interpreted this to mean that merit can only lead to happiness and progress within Saṃsāra, but does not lead to Nirvana, and must in fact be discarded before attaining Nirvana.[112][113][114] Marasinghe believes, however, that the word merit in this passage refers to merit in the pre-Buddhist Brahmanical sense, connected with rituals and sacrifice, and the lay life.[115] Another example often quoted in this context is the simile of the raft, which states that both dhamma and adhamma should be let go of in order to attain liberation. Whereas the term adhamma in the text clearly refers to evil views, the meaning of dhamma is subject to different interpretations. Considering that no other similar passage can be found in the Tipiṭaka, Keown believes that only this passage is not enough to base the transcendency thesis on.[116]

In the Pāli Canon, an enlightened person is said to be neutral in terms of karma, that is, the person no longer generates karma, merit, or demerit.[5][117][118] Some scholars have interpreted this to mean that an enlightened person attains a state where distinctions between good and evil no longer exist. Other scholars have criticized this as making little sense, considering how the Buddha would normally emphasize ethics. The fact that an enlightened person is neutral in terms of karma, does not mean he is ethically neutral.[119][120] Indeed, the Buddha is quoted in the Tipiṭaka as saying he is foremost in 'higher morality' (adhisīla).[121] Keown attempts to overcome this problem by proposing that enlightened people are beyond the accumulative experience of good deeds (merit, puñña), since they are already perfected. They therefore do not need to accumulate goodness and the resulting happiness anymore. They no longer need to strive for a happy rebirth in the next life, because they have gone beyond rebirth. Their enlightenment is, however, an ethical perfection as well, though this is solely described as kusala, not as puñña.[122][123][124]

Field of merit

In pre-Buddhist Brahmanism, Brahmin priests used to perform yajñas (sacrifices) and thereby generating merit for the donors who provided gifts for the sacrifice. In Buddhism, it was the Buddhist monk who assumed this role, considered qualified to receive generosity from devotees and thereby generating merit for them. He came to be described as āhuneyyo ('worthy of offering'), by analogy with the Brahmanical term āhavanīya ('worthy of sacrifice', used in offerings to the ritual fire); and as dakkhiṇeyyo ('qualified to accept the offering'), by analogy with the Brahmanical dakśiṇā, the sacrificial offering itself.[126][127][128] The Sangha (monastic community) was also described as 'field of merit' (Pali: puññakkhetta; Sanskrit: puṇyakṣetra).[129][130][131] The difference with the Brahmanical tradition was, according to Marasinghe, that Buddhism did recognize other ways of generating merit apart from offerings to the monk, whereas the Brahmanical yajña only emphasized offerings to the Brahmin priest. That is not to say that such offerings were not important in early Buddhism: giving to the Sangha was the first Buddhist activity which allowed for community participation, and preceded the first rituals in Buddhism.[126]

The main concept of the field of merit is that good deeds done towards some recipients accrue more merit than good deeds to other recipients. This is compared with a seed planted in fertile ground which reaps more and better fruits than in infertile ground.[49][125][132] The Sangha is described as a field of merit, mostly because the members of the Sangha follow the Noble Eightfold Path. But in many texts, the Buddha and the Dhamma, and their representations, are also described as fields of merit. For example, Mahāyāna tradition considers production and reverence of Dharma texts very meritorious—this tradition, sometimes referred to as the "cult of the book" (Gregory Schopen), stimulated the development of print technology in China.[133][134][135] In other traditions a Buddha image is also considered a field of merit, and any good deed involving a Buddha image is considered very meritorious.[136][137] A meritorious deed will also be very valuable (and sometimes viewed in terms of a field of merit) if performed to repay gratitude to someone (such as parents), or performed out of compassion for those who suffer.[16][138][139] Deeds of merit done towards the Sangha as a whole (Pali: saṅghadāna) yield greater fruits than deeds done towards one particular recipient (Pali: pāṭipuggalikā dakkhiṇā) or deeds done with favoritism.[77][66][140] Indeed, saṅghadāna yields even more fruits than deeds of merit to the person of the Buddha himself.[78][141]

Practice in Buddhist societies

Thus the Buddhist's view of his present activities has a wider basis, they being but one group of incidents in an indefinitely prolonged past, present and future series. They are, as has been said, no mere train of witnesses for or against him, but a stage in a cumulative force of tremendous power. He and his works stand in a mutual relation, somewhat like that of child to parent in the case of past works, of parent to child in the case of future works. Now no normal mother is indifferent as to whether or how she is carrying out her creative potency. Nor can any normal Buddhist not care whether his acts, wrought up hourly in their effect into his present and future character, are making a happy or a miserable successor. And so, without any definite belief as to how, or in what realm of the universe he will re-arise as that successor to his present self, the pious Buddhist, no less than his pious brethren of other creeds, goes on giving money and effort, time and thought to good works, cheerfully believing that nothing of it can possibly forgo its effect, but that it is all a piling up of merit or creative potency, to result, somewhere, somewhere, somehow, in future happiness—happiness which, though he be altruistic the while, is yet more a future asset of his, than of some one in whom he naturally is less interested than in his present self. He believes that, because of what he is now doing, some one now in process of mental creation by him, and to all intents and purposes his future " self," will one day taste less or more of life's trials. To that embryonic character he is inextricably bound ever making or marring it, and for it he is therefore and thus far responsible.

C. A. F. Rhys Davids, A Study of the Buddhist Norm[142]

Merit-making

The ten bases of merit are very popular in Buddhist countries.[65] In China, other similar lists are also well-known.[143][144] In Thai Buddhism, the word "merit" (RTGS: bun) is often combined with "to do, to make" (RTGS: tham), and this expression is frequently used, especially in relation to giving.[145][146][147][note 5] In Buddhist societies, such merit-making is common, especially those meritorious deeds which are connected to monks and temples. In this regard, there is a saying in Burma, "Your hands are always close to offering donations".[18][146][149] Contrary to popular conceptions, merit-making is done by both monastics and laypeople alike.[150][151][152] Buddhist monks or lay Buddhists earn merit through mindfulness, meditation, chanting and other rituals. Giving is the fundamental way of making merit for many laypeople, as monks are not allowed to cook by themselves.[31] Monastics in their turn practice themselves to be a good field of merit and make merit by teaching the donors. Merit-making has thus created a symbiotic relationship between laypeople and Sangha,[77][66][153] and the Sangha is obligated to be accessible to laypeople, for them to make merit.[154]

Giving can be done in several ways. Some laypeople offer food, others offer robes and supplies, and others fund ceremonies, build monasteries or persuade a relative to ordain as a monk. Young people often temporary ordain as monks, because they believe this will not only yield fruits of merit for themselves, but also for their parents who have allowed them to ordain.[155][156][157] In China, Thailand and India, it used to be common to offer land or the first harvest to a monastery.[158][153][159] Also, more socially oriented activities such as building a hospital or bridge, or giving to the poor are included in the Tipiṭaka, and by many Buddhists considered meritorious.[112][151][160] In fieldwork studies done by researchers, devotees appreciated the merits of becoming ordained and supporting the building of a temple the most.[157][161] Fisher found that building a temple was considered a great merit by devotees, because they believed they would in that way have part in all the wisdom which would be taught at that temple.[162] People may pursue merit-making for different reasons, as Buddhist orthodoxy allows for various ideals, this-worldly or ultimate.[163] Although many scholars have pointed out that devotees often aim for this-worldly benefits in merit-making,[164][165] it has also been pointed out that in old age, people tend to make merit with a view on the next life and liberation.[165][166] Among lay people, women tend to engage in merit-making more than men, and this may be a way for them to enhance empowerment.[31][167][168] Very often, merit-making is done as a group, and it is believed that such shared merit-making will cause people to be born together in next lives. This belief holds for families, friends, communities and even the country as a whole.[169][170] In some cases, merit-making took the form of a community-wide competition, in which different donors tried to outdo each other to prove their generosity and social status. This was the case during merit-making festivals in nineteenth-century Thailand.[18][171] In modern Thailand, businesses and politicians often make merit to improve their public image and increase confidence among customers or voters.[172] In Burma, lay devotees form associations to engage in merit-making as a community.[173]

People were so intent on merit-making and giving, that in some societies, people would even offer themselves and their family to a Buddhist temple, as one high-ranking minister did in the ancient Pagan Kingdom (ninth until fourteenth century Burma).[175][176] On a similar note, in Sri Lanka, kings and commoners would offer slaves to the temple, and then donate money to pay for their freedom, that way accruing two merits at once. Even more symbolically, kings would sometimes offer their kingdom to a temple, which, returned the gift immediately, together with some Dhamma teaching. Also in Sri Lanka, King Mahakuli Mahatissa disguised himself as a peasant and started to earn his living working on a paddy field, so he would be able to gain more merit by working himself to obtain resources to give to Buddhist monks.[177] In some cases, merit-making was even continued after a person's death: in ancient Thai tradition, it was considered meritorious for people to dedicate their corpses to feed the wild animals after death.[178]

Rituals

Many devout Buddhists observe regular "rest days" (Pali: uposatha) by keeping five precepts, listening to teachings, practicing meditation and living at the temple.[179][180] Besides these weekly observances, ceremonies and festivities are yearly held and are often occasions to make merit,[29][181] and are sometimes believed to yield greater merits than other, ordinary days.[182] In Thailand and Laos, a yearly festival (RTGS: Thet Mahachat) is held focused on the Vessantara Jātaka, a story of a previous life of the Buddha which is held sacred.[181][174] This festival, seven centuries old, played a major role in legitimating kingship in Thai society. Making merit is the central theme of the festival. Since the period of Rama IV, however, the festival has become less popular.[183][184] Many countries also celebrate the yearly Kaṭhina, when they offer robes, money and other requisites to the Sangha as a way to make merit.[185][186] In Burma, the two yearly Light Festivals are typically occasions to make merit, as gifts are given to elders, and robes are sewn for the Sangha.[187] In South Korea, a Buddha Day (Korean: seog-ga-tan-sin-il) is held, on which Buddhists pray and offer alms.[188] Other kinds of occasions of merit-making are also uphold. A special form of merit-making less frequently engaged in is going on pilgrimage, which is mostly common in Tibet and Japan. This practice is highly regarded and considered very meritorious.[189][190]

Recording

In several Buddhist countries, it has been common to record merits done. In China, it was common for many centuries to keep record of someone's meritorious deeds in 'merit ledgers' (pinyin: gōngguò gé). Although a belief in merit and retribution had preceded the merit ledgers by many centuries, during the Ming dynasty, through the ledgers a practice of systematic merit accumulation was established for the first time. The merit ledgers were lists of good deeds and bad deeds, organized in the form of a calendar for users to calculate to what extent they had been practicing good deeds and avoiding bad deeds every day. The ledgers also listed the exact retributions of every number of deeds done, to the detail. Through these ledgers it was believed someone could offset bad karma.[191][192] In the fourth century CE, the Baopuzi, and in the twelfth century the Treatise On the Response of the Tao and the Ledger of Merit and Demerit of the Taiwei Immortal introduced the basics of the system of merit ledgers. In the fourteenth century CE, the Tao master Zhao Yizhen recommended the use of the ledgers to examine oneself, to bring emotion in harmony with reason.[193][194] From the fourth to the sixteenth centuries, many types of ledgers were produced by Buddhist and Tao schools, and the usage of the ledgers grew widespread.[195] The practice of recording merits has survived in China and Japan until the present day.[196] In Theravāda countries, for example in Burma and Sri Lanka, similar customs have been observed.[197][198] In Sri Lanka, a 'book of merit' (Pali: puñña-potthaka, Sanskrit: puṇyapustaka) was sometimes kept by someone for years and read in the last moments of life. This practice was based on the story of King Duṭṭhagāmaṇi, and was mostly practiced by the royalty and rich during the period of the Mahāvaṁsa chronicle.[199][200][201] More recent practice has also been observed, for example, as a form of terminal care.[202][203] or as part of the activities of lay merit-making associations.[204]

Merit and wealth

The association of wealth with merits done has deeply affected many Buddhist countries. The relation between giving and wealth is ubiquitous in vernacular Pāli literature, and many stories of exemplary donors exist, such as the stories of Anāthapiṇḍika and Jōtika.[205] In Buddhism, by emphasizing the usage of wealth for generosity, accumulating wealth for giving purposes thus became a spiritual practice.[15] But using wealth in unrighteous ways, or hoarding it instead of sharing and giving it, is condemned extensively. Taṇhā (thirst, desire, greed, craving) is what keeps a person wandering in Saṃsāra (the cycle of rebirth), instead of becoming liberated. It is the attachment to wealth that is an obstacle on the spiritual path, not wealth per se. Stories illustrating these themes in vernacular Buddhist literature, have profoundly influenced popular culture in Buddhist countries.[122][206][205] Several scholars have described merit as a sort of spiritual currency or bookkeeping system.[44][197][207] Though objections have been made against this metaphor,[203][208] it is not new. Similar comparisons have been made in the Milinda Pañhā, and in seventeenth-century China. Moreover, Schopen has shown that Buddhism has had strong connections with the mercantile class, and Rotman thinks that a mercantile ethos may have informed Buddhist texts such as the Divyāvadāna.[102][197] Gombrich objects to calling merit-making "dry metaphysical mercantilism", but he does speculate on a historical relation between the concept of merit and the monetization of ancient India's economy.[209]

Transfer

Description and origins

Two practices mentioned in the list of meritorious acts have been studied quite extensively by scholars: dedicating (or transferring) merit to others, and rejoicing in others' merits.[211] Transferring merit is a widespread custom in all Buddhist countries, Mahāyāna, Vajrayāna and Theravāda.[212][213][214] In the Pāli tradition, the word pattidāna is used, meaning 'giving of the acquired'.[215] And in the Sanskrit tradition, the word pariṇāmanā is used for transferring merit, meaning 'bending round or towards, transfer, dedication'.[216] Of these translations, 'transfer of merit' has become commonplace, though objected to by some scholars.[217][218]

Buddhist traditions provide detailed descriptions of how this transfer proceeds. Transferring merit to another person, usually deceased relatives, is simply done by a mental wish. Despite the word transfer, the merit of the giver is in no way decreased during such an act, just like a candle is used to light another candle, but the light does not diminish.[64][74][219] The merit transferred cannot always be received, however. The dead relatives must also be able to sympathize with the meritorious act. If the relatives do not receive the merit, the act of transferring merit will still be beneficial for the giver himself. The transfer of merit is thus connected with the idea of rejoicing.[220] The other person who rejoices in one's meritorious deeds, in that way also receives merit, if he approves of the merit done. Thus, rejoicing in others' merits, apart from being one of the ten meritorious acts mentioned, is also a prerequisite for the transferring of merit to occur.[43][219][221] The purposes for merit transfer differ. In many Buddhist countries, transferring merit is connected to the notion of an intermediate state. The merit that is transferred to the deceased will help them to cross over safely to the next rebirth.[222] Some Mahāyāna traditions believe that it can help deceased relatives to attain the Pure Land.[16] Another way of transferring merit, apart from helping the deceased, is to dedicate it to the devas (deities), since it is believed that these are not able to make merits themselves. In this way it is believed their favor can be obtained.[44][221][223] Finally, many Buddhists transfer merits to resolve a bond of revenge that may exist between people, as it is believed that someone else's vengefulness may create harm in one's life.[196][224]

Initially in the Western study of Buddhism, some scholars believed that the transfer of merit was a uniquely Mahāyāna practice and that it was developed only at a late period after the historical Buddha. For example, Heinz Bechert dated the Buddhist doctrine of transfer of merit in its fully developed form to the period between the fifth and seventh centuries CE.[225] Scholars perceived that it was discordant with early Buddhist understandings of karma,[213][225][226] and noticed that in the Kathāvatthu the idea is partly refuted by Theravādins.[227][228] Other scholars have pointed out that the doctrine of the transfer of merit can be found early in the Theravāda tradition.[214][229][230] Then there also scholars who propose that, although the transfer of merit did not exist as such in early Buddhism, early doctrines did form a basis for it, the transfer of merit being an "inherent consequence" (Bechert) of these early doctrines.[231][232][233]

The idea that a certain power could be transferred from one to another was known before the arising of Buddhism. In religious texts such as the Mahābhārata, it is described that devas can transfer certain powers (Sanskrit: tejas). A similar belief existed with regard to the energy gained by performing austerities (Sanskrit: tapas). Apart from these transfers of power, a second origin is found in Brahamanical ancestor worship.[74] In the period preceding the arising of Buddhism, it was believed that after a person's death he had to be transformed from a wandering preta to reach the blissful world of the pitṛs. This was done through the complex Śrāddha ceremonies, which would secure the destiny of the deceased as a pitṛ. In Buddhism, however, ancestor worship was discontinued, as it was believed that the dead would not reach heavenly bliss through rituals or worship, but only through the law of karma. Nevertheless, the practice of transfer of merit arose by using the ethical and psychological principles of karma and merit, and connect these with the sense of responsibility towards one's parents. This sense of responsibility was typical for pre-Buddhist practices of ancestor worship. As for the veneration of dead ancestors, this was replaced by veneration of the Sangha.[234][235]

Application in the spreading of Buddhism

Sree Padma and Anthony Barber note that merit transfer was well-established and a very integral part of Buddhist practice in the Andhra region of southern India.[236] In addition, inscriptions at numerous sites across South Asia provide definitive evidence that the transfer of merit was widely practiced in the first few centuries CE.[237][238] In Theravāda Buddhism, it has become customary for donors to share merits during ceremonies held at intervals, and during a teaching.[239][240][221] In Mahāyāna Buddhism, it is believed that Bodhisattvas in the heavens are capable of transferring merits, and will do so to help relief the suffering of their devotees, who then can dedicate it to others. This concept has led to several Buddhist traditions focused on devotion.[241][242][243] Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna Buddhists transfer merits as part of the 'Seven-part-worship' (Sanskrit: saptāṇgapūjā),[244][245][246][note 6] and there is almost no ceremony without some form of merit transfer.[23][248] Thus, merit transfer has developed to become a standard element in the basic liturgy of all main schools of Buddhism. Indeed, the transfer of merits has grown that important in Buddhism, that it has become a major way for Buddhism to sustain itself.[16] In Japan, some temples are even called ekōdera, which means a temple for merit transfer.[249]

Kingship

%252C_in_the_Guimet_Museum_(Paris).jpg.webp)

In South and South-East Asia, merit-making was not only a practice for the mass, but was also practiced by the higher echelons of society. Kingship and merit-making went together.[175][251] In the Tipiṭaka, ideas about good governance were framed in terms of the ideal of the 'wheel-turning monarch' (Pali: Cakkavatti; Sanskrit: Cakravartin), the king who rules righteously and non-violently according to Dharma.[252] His roles and duties are discussed extensively in Buddhist texts. The Cakkavatti is a moral example to the people and possesses enough spiritual merit. It is through this that he earns his sovereignty, as opposed to merely inheriting it.[253][254] Also, the Buddha himself was born as a prince, and was also a king (Vessantara) in a previous life.[214][255][256] Apart from the models in the suttas, Pāli chronicles such as the Mahāvaṃsa and the Jinakālamālī may have contributed to the ideals of Buddhist kingship. In these vernacular Pāli works, examples are given of royalty performing meritorious acts, sometimes as a form of repentance for previously committed wrongdoings. The emperor Asoka (Sanskrit: Aśoka) is featured as an important patron supporting the Sangha.[250]

Because of these traditions, kings have had an important role in maintaining the Sangha, and publicly performed grand acts of merit, as is testified by epigraphic evidence from South and South-East Asia.[216][251] In Sri Lanka, from the tenth century CE onward, kings have assumed the role of a lay protector of the Sangha, and so have Thai kings, during the periods of Sukhothai and Ayutthaya (fourteenth until eighteenth centuries). In fact, a number of kings in Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Burma have described themselves as Bodhisattas, and epithets and royal language were established accordingly.[175][257][258] In short, kingship in traditional Buddhist societies was connected with the Sangha as a field of merit: the king assumed an exemplary role as a donor to the Sangha, and the Sangha legitimated the king as a leader of the state. Both facilitated one another, and both needed each other.[259] In times of famine or other hardship, it was traditionally believed that the king was failing, and the king would typically perform meritorious activities on a grand scale.[197][260][261] In this way the king would be able to improve the kingdom's conditions, through his "overflow karma" (Walters).[262] A similar role was played by queens.[263]

In the last seven centuries in Thailand, the Vessantara Jātaka has played a significant role in legitimating kingship in Thailand, through a yearly festival known as the 'Preaching of the Great Life' (RTGS: Thet Mahachat). Merit-making and pāramīs (doing good deeds, developing good habits to become a Buddha) were greatly emphasized in this festival, through the story about Prince Vessantara's generosity. During the reform period of Rama IV, as Thai Buddhism was being modernized, the festival was dismissed as not reflecting true Buddhism. Its popularity has greatly diminished ever since. Nevertheless, the use of merit-making by the Thai monarchy and government, to solidify their position and create unity in society, has continued until the late twentieth century.[264]

In modern society

19th–early 20th century

Buddhists are not in agreement with regard to the interpretation, role, and importance of merit. The role of merit-making in Buddhism has been discussed throughout Buddhist history, but much more so in the last centuries. In the nineteenth century, during the rise of Buddhist modernism and the Communist regimes, Buddhists in South and Southeast Asia became more critical about merit-making when it became associated with magical practices, privileging, ritualism and waste of resources.[265][266][267][note 7] In pre-modern Thailand, a great deal of the funds of temples were derived from the profits of land that were offered to temples by royalty and nobility. During the period of religious reform and administrative centralization in the nineteenth and early twentieth century, however, Thai temples were no longer supported in this manner and had to find other ways to maintain themselves.[159]

At the beginning of the twentieth century, perspectives of merit-making had changed again, as merit-making was being associated with capitalism and consumerism, which had been rising in South and Southeast Asia.[270][271] Furthermore, in some Buddhist countries, such as Thailand, there is a tendency among teachers and practitioners to dismiss and even revile merit-making in favor of teachings about detachment and attaining Nirvana, for which L. S. Cousins has coined the term "ultimatism".[272][273][274]

From 1960s onward

Studies done in the 1960s and 1970s in Thailand, Sri Lanka and Burma showed that a great deal of time, effort and money was invested by people in merit-making, e.g. Spiro described Burma's rural economy as "geared to the overriding goal of the accumulation of wealth as a means of acquiring merit". In some studies done in rural Burma, up to thirty percent of people's income was spent on merit-making.[275] In 2014, when Burma ranked highest on the World Giving Index (tied with the United States, and followed by many other Buddhist countries), scholars attributed this to the Burmese habit of merit-making.[18][276] Studies done in Thailand, however, showed that in the 1980s merit-making was declining, and a significant group did no longer believe in karma—though this was not a majority.[277] Some scholars disagree with these findings, however, saying that Buddhist practices such as merit-making are still very widespread.[271] Similar observations have been made about Cambodia and even about Thai people in the United States.[278][279] As for Buddhist "converts" in the west, for example from the United Kingdom, the interest in merit is less than among Asian Buddhists, but they strongly appreciate the generosity and reverence as exhibited by Asian Buddhists.[280][281]

| Region | Baht/Person/Year |

|---|---|

| Bangkok Metropolitan Area | 1,512 |

| Central | 1,032 |

| North | 672 |

| Northeast | 492 |

| South | 516 |

| National average | 804 |

Discussion by scholars

Some scholars have suggested that merit-making may have affected the economies of Buddhist countries in a negative way, because spending savings on the local temple would prevent consumption and investment and therefore stunt economic growth. Other researchers have disagreed, pointing out that spending resources on a Buddhist temple does stimulate economic growth through the investment in goods for the temple.[29][282][note 8] It has also been suggested that even if the economy of Buddhist countries would be better off without merit-making, it would result in an economy that the majority of the population would not prefer. Another criticism often leveled at merit-making in modern times is that it prevents people from using their resources to help the poor and needy. Very often, however, temples do have many social roles in society, and offer help to many groups in society—resources are therefore redistributed widely.[284][285] Moreover, since merit-making is often done as a community, merit-making may strengthen social ties, which Walters calls "sociokarma".[286]

Scholars have often connected the notion of karma to the determinism in the caste system in India.[287] Just like in the case of karma, some scholars believe that a belief in merit can cause social differences to stay unchanged. This would be the case when the poor, who cannot make much merit, resign to their fate.[288][289] Other scholars point out that merit can be used to improve social status in the present, as in the case of someone ordaining as a monk for a few years.[214] And vice versa, if someone's social status quickly deteriorates, for example, due to quick changes in the bureaucratic structure, these changes might be justified in Buddhist societies because someone's store of merit is believed to have run out.[290] Someone's position in society, even in the cosmos, is always subject to the impermanent workings of merit and demerit. In traditional Buddhist societies, quick changes in position, status, or roles are therefore considered part of life, and this insecurity is a motivator in trying to improve the situation through merit-making.[291][292] Findly points out that in Buddhist ideals of merit-making, the earned value gained by doing good deeds is more important than the assigned value gained by social status at birth.[293]

Phu Mi Bun movements

The idea of merit is also at the basis of the Phu Mi Bun movements as has been studied in Thailand and other Buddhist societies. Phu Mi Bun are people who are considered to have much merit from past lives, whose influence morally affects society at large.[294][295][296] Phu Mi Bun are in many ways similar to people declared Bodhisattvas in Buddhist societies, and in fact, the word Phu Mi Bun is often used in traditional Thai texts about the previous lives of the Buddha. Besides the example of the king himself, certain monks and shamans have assumed this role throughout history. In Thailand, around the turn of the twentieth century, a millennialist movement arose regarding the coming of a Phu Mi Bun, to the extent of becoming an insurgency which was suppressed by the government.[297][298][299] This insurgency became known to Thai historians as the "rebellion of the Phu Mi Bun" (RTGS: Kabot Phu Mi Bun), commonly known in English as the Holy Man's Rebellion.[300] Several of such rebellions involving Phu Mi Bun have taken place in the history of Thai, Laos, Cambodia and Burma. For example, in Cambodia, there were Phu Mi Bun–led revolts against the French control of Cambodia.[301] Lucien Hanks has shown that beliefs pertaining to Phu Mi Bun have profoundly affected the way Thai people relate to authority.[40] Indologist Arthur Basham, however, believed that in contemporary Thai society the Phu Mi Bun is more of a label, and merit more of a secular term than a deeply-rooted belief.[302]

Merit release

One merit-making practice that has received more scholarly attention since the 1990s is the practice of "merit release". Merit release is a ritual of releasing animals from captivity, as a way to make merit. Merit release is a practice common in many Buddhist societies, and has since the 2010s made a comeback in some societies.[303] Its origins are unclear, but traditionally it is said to originate from the Mahāyāna Humane King Sutra, among other sources.[304][305] It often involves a large number of animals which are released simultaneously, as well as chanting, making a resolution, and transfer of merits.[306][307] Though the most common practice is the releasing of fish and birds back in nature, there are also other forms: in Tibet, animals are bought from the slaughterhouse to release.[308] However, the practice has come under criticism by wildlife conservationists and scholars. Studies done in Cambodia, Hong Kong and Taiwan have shown that the practice may not only be fatal for a high percentage of the released animals, but may also affect the survival of threatened species, create a black market for wildlife, as well as pose a threat for public hygiene.[304][309] In Thailand, there are cases where animals are captured for the explicit purpose of being sold to be released—often into unsuitable ecosystems.[310] Some Buddhist organizations have responded to this by adjusting their practices, by working together with conservationist organizations to educate people, and even by pushing for new laws controlling the practice.[311] In 2016, the Society for Conservation Biology (SCB) started discussing possible solutions with religious communities on how the practice could be adapted. According to the SCB, the communities have generally responded positively.[304][312] In the meantime, in some countries, laws have been issued to control the practice. In Singapore, to limit merit release on Vesak celebrations, people were fined.[305]

Despite its critics, merit release continues to grow, and has also developed new forms in western countries. In 2016, it was widely reported that the Canada-based Great Enlightenment Buddhist Institute Society (GEBIS) had released 600 pounds (270 kg) of lobsters in the ocean. The release was planned in agreement with local lobster-men.[313] In the same year, Wendy Cook from Lincoln, United States, bought fourteen rabbits from a farm to raise them under better conditions. The costly release, advertised on Facebook as The Great Rabbit Liberation of 2016, was supported by Buddhist monastics from Singapore and the Tibetan tradition, and was based on the idea of merit-making.[314] In a less successful attempt, two Taiwanese Buddhists released crab and lobsters in the sea at Brighton, United Kingdom, to make merit. They were fined by the authorities for £15,000 for a wildlife offense that could have significant impact on native species.[315]

See also

- Three Refuges

- Noble Eightfold Path

- Sukha

- Karma in Buddhism

Notes

- In the Sangīti Sutta ("Chanting together discourse," Digha Nikaya 33), verse 38, the leading disciple Sāriputta is described as teaching the same triad: dāna, sīla, bhāvanā.[55]

- See Digha Nikāya iii.218

- The announcing of a certain intention in reference to the actions someone has done (Pali: saccakiriya) is a common theme in all Indian religion [84]

- There is some discussion as to the best translation of kusala, some preferring 'skilful' or 'intelligent' instead.[93]

- However, the term merit-making may also originate from a translation of Pāli terms. In Pāli texts several of such terms were used.[148]

- There are also other forms that are practiced, varying from four to eleven parts.[247]

- From the 1980s onward, the communist regimes in Laos and Cambodia no longer viewed Buddhism as an obstacle to the development of the state, and many of the restrictions with regard to Buddhist practice were lifted. [50][268] In Burma, the former military government approached merit-making practices differently: they justified their forced labor camps by citing that the labor there yielded merit. At the same time, Aung San Suu Kyi referred to the struggle for democracy as meritorious.[269]

- Since the 2000s, studies in China have shown a growing interest among local government officials to promote merit-making activities, believing it to stimulate local economy.[283]

Citations

- Spiro 1982, p. 141.

- Rhys Davids & Stede 1921, p. 86.

- Marasinghe 2003, p. 461.

- Harvey 2012, p. 44.

- Nyanatiloka 1980b.

- Pye & Strong 1987, pp. 5870, 5873.

- Hanks 1962, p. 1247.

- Harvey 2000, p. 18.

- Cousins 1996, p. 155.

- Holt 1981.

- Marasinghe 2003, pp. 457–8.

- Premasiri 1976, p. 66.

- Shohin, V.K. (2010). ПАПА–ПУНЬЯ [pāpa–puñña]. New Encyclopedia of Philosophy (in Russian). Institute of Philosophy of the Russian Academy of Sciences, National public and Science Foundation.

- Norman, K.R. (1992). "Theravāda Buddhism and Brahmanical Hinduism: Brahmanical Terms in a Buddhist Guise". In Skorupski, Tadeusz (ed.). The Buddhist forum: Seminar Papers 1988–90. New Delhi: Heritage Publishers. pp. 197–8. ISBN 978-81-7026-179-7.

- Findly 2003, p. 2.

- Tanabe 2004, p. 532.

- McFarlane 1997, p. 409.

- Fuller, Paul (4 September 2015). "The act of giving: what makes Myanmar so charitable?". Myanmar Times. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Marasinghe 2003.

- Basham 1989, p. 126.

- Terwiel, B. J. (1 January 1976). "A Model for the Study of Thai Buddhism". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (3): 391–403. doi:10.2307/2053271. JSTOR 2053271. S2CID 162810180.

- Egge 2013, p. 21.

- Gutschow 2004, p. 14.

- Gombrich 2009, p. 44.

- Hanks 1962, p. 1254.

- Brokaw 2014, p. 28.

- Keyes 1973, p. 96.

- Gombrich 1971, pp. 204–5.

- "Thai Merit-Making: Bt3.3 Billion Cashflow for Merchants". Kasikorn Research Center. 22 February 2005. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Keyes 1983, p. 268.

- Cate & Lefferts 2006, p. 589.

- Scott 2009, p. 29.

- Williams 2008, p. 158.

- Rao, K. Ramakrishna; Paranjpe, Anand C. (2015). Cultural Climate and Conceptual Roots of Indian Psychology. Psychology in the Indian Tradition. Springer India. pp. 47–8. doi:10.1007/978-81-322-2440-2_2. ISBN 978-81-322-2440-2.

- Elucidation of the intrinsic meaning so named the Commentary on the Vimāna stories (Paramattha-dīpanī nāma Vimānavatthu-aṭṭhakathā). Translated by Masefield, Peter; Jayawickrama, N.A. (1 ed.). Oxford: Pali Text Society. 1989. pp. xxxv, xlv. ISBN 978-0-86013-272-1.

- Gutschow 2004, p. 2.

- The connected discourses of the Buddha: a new translation of the Saṃyutta Nikāya (PDF). Translated by Bodhi, Bhikkhu. Boston: Wisdom Publications. 2001. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-86171-188-8.

- Marasinghe 2003, p. 460.

- Harvey 2000, p. 19.

- Hanks 1962.

- Keyes 1983, pp. 267–8.

- Marasinghe 2003, p. 471.

- Harvey 2000, p. 20.

- Langer, Rita (2007). Buddhist Rituals of Death and Rebirth: Contemporary Sri Lankan Practice and Its Origins. Routledge. Introduction. ISBN 978-1-134-15872-0.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 127.

- Gutschow 2004, p. 15.

- Patrick, Jory (1996). A History of the Thet Maha Chat and its Contribution to a Thai Political Culture (original Ph.D. Thesis). Australian National University. p. 74.

- Skilling 2005, pp. 9832–3.

- Salguero 2013, p. 342.

- Cate & Lefferts 2006, p. 590.

- Calkowski, Marcia (2006b). "Thailand" (PDF). In Riggs, Thomas (ed.). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices. Vol. 3. Farmington Hills: Thomson-Gale. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-7876-6614-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Anusaraṇaśāsanakiarti, Phra Khrū; Keyes, Charles F. (1980). "Funerary rites and the Buddhist meaning of death: An interpretative text from Northern Thailand" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 68 (1): 18.

- Mulder 1969, p. 109.

- Mulder 1969, pp. 109–10.

- Walshe 1995, p. 485.

- Findly 2003, pp. 185, 250.

- Lehman, F. K. (1 January 1972). "Doctrine, Practice, and Belief in Theravada Buddhism (Review of Buddhism and Society: A Great Tradition and its Burmese Vicissitudes by Melford E. Spiro)". The Journal of Asian Studies. 31 (2): 373–380. doi:10.2307/2052605. JSTOR 2052605. S2CID 162817978.

- Jones 1979, p. 372.

- Namchoom & Lalhmingpuii 2016, p. 47.

- Jones 1979, p. 374.

- Salguero 2013, p. 344.

- Skilling 2005, p. 9832.

- Marasinghe 2003, pp. 460, 462.

- Marasinghe 2003, p. 470.

- Nyanatiloka 1980c, p. 275.

- Pye & Strong 1987, p. 5873.

- Gutschow 2004, pp. 14–5.

- Spiro 1982, pp. 105–7.

- Keown 1992, p. 13.

- Neusner, Jacob; Chilton, Bruce (2008). The golden rule: the ethics of reciprocity in world religions. London: Continuum. p. 117. ISBN 978-1-4411-9012-3.

- Harris, Stephen E. (2015). "On the Classification of Śāntideva's Ethics in the Bodhicaryāvatāra". Philosophy East and West. 65 (1): 249–275. doi:10.1353/pew.2015.0008. S2CID 170301689.

- Perrett, Roy W. (March 1987). "Egoism, altruism and intentionalism in Buddhist ethics". Journal of Indian Philosophy. 15 (1): 71–85. doi:10.1007/BF00213993. S2CID 170376011.

- Keown 1992, pp. 74–6.

- Pye & Strong 1987, p. 5874.

- Williams 2008, pp. 45, 57, 59.

- Skilling 2005, pp. 9833, 9839.

- Heim, Maria (2004). "Dāna" (PDF). In Buswell, Robert E. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Vol. 2. New York (u.a.): Macmillan Reference USA, Thomson Gale. p. 196. ISBN 978-0-02-865720-2.

- Brekke 1998, p. 301.

- Spiro 1982, pp. 108–9.

- Scott 2009, p. 94.

- Harvey 2000, pp. 19, 21–2.

- Brekke 1998, pp. 301, 309–10.

- de La Vallée Poussin, Louis (1917). The way to Nirvana: Six lectures on ancient Buddhism as a discipline of salvation. Hibbert lectures. Library of Alexandria. ISBN 978-1-4655-7944-7.

- Marasinghe 2003, p. 468.

- Walters 2003, pp. 23–4.

- Gómez 2002, pp. 30–1.

- Harvey 2000, pp. 20–1, 192.

- Spiro 1982, p. 110.

- Findly 2003, p. 260.

- Bhikkhu, Saddhaloka. "The Discourse on the Ten Wholesome Ways of Action". Buddhistdoor. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- "The discourse on the ten wholesome ways of action". Undumbara Garden. 23 September 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2014.

- Marasinghe 2003, pp. 459, 464.

- Cousins 1996, pp. 137–8.

- Gómez 2002, pp. 324–5.

- Thomas 1953, p. 120.

- Premasiri 1976.

- Marasinghe 2003, pp. 463–5.

- Keown 1992, p. 123.

- Marasinghe 2003, p. 467.

- Keown 1992, p. 90.

- Egge 2013, pp. 55–6.

- Collins 1997, p. 290.

- Spiro 1982, p. 95.

- Collins 1997, p. 482.

- Collins 1997, p. 495.

- Payutto, Phra (1993). พจนานุกรมพุทธศาสน์ ฉบับประมวลศัพท์ พจนานุกรมพุทธศาสตร์ ฉบับประมาลศัพท์ [Dictionary of Buddhism, Vocabulary] (PDF) (in Thai) (7 ed.). Bangkok: Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University. pp. 25–6, 179. ISBN 978-974-575-029-6.

- Cousins 1996, pp. 154–5.

- Spiro 1982.

- Aronson, Harvey B. (1 January 1979). "The Relationship of the Karmic to the Nirvanic in Theravāda Buddhism". The Journal of Religious Ethics. 7 (1): 28–36. JSTOR 40018241.

- Swearer 1995, p. 10.

- Keown 1992, pp. 85–105.

- Premasiri 1976, p. 68.

- Keown 1992, p. 89.

- Egge 2013, p. 23.

- Marasinghe 2003, pp. 462–3.

- Keown 1992, pp. 94–105.

- Marasinghe 2003, pp. 466, 471.

- McDermott 1975, pp. 431–2.

- Premasiri 1976, p. 73.

- Marasinghe 2003, pp. 465–6.

- Keown 1992, p. 113.

- Goodman, Charles (2009). Consequences of Compassion: An Interpretation and Defense of Buddhist Ethics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988845-0.

- Keown 1992, pp. 90, 124, 127–8.

- Spiro 1982, p. 43.

- Brekke 1998, pp. 299–300.

- Marasinghe 2003, p. 459.

- Egge 2013, pp. 19–20.

- Findly 2003, pp. 217–8, 222.

- Rhys Davids & Stede 1921, p. 87.

- Brekke 1998, p. 299.

- Egge 2013, p. 20.

- Adamek 2005, p. 141.

- Gummer, Nathalie (2005). "Buddhist Books and Texts: Ritual Uses of Books" (PDF). In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson Gale. pp. 1261–4. ISBN 978-0-02-865735-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Williams 2008, pp. 45, 145, 149.

- Kieschnick, John (2003). The impact of Buddhism on Chinese material culture. New Jersey: University Presses of California, Columbia and Princeton. pp. 180–1. ISBN 978-0-691-09676-6.

- Morgan, David (2005). "Buddhism: Buddhism in Tibet" (PDF). In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 14 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson Gale. p. 9623. ISBN 978-0-02-865983-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Skilling 2005, p. 9829.

- Salguero 2013, p. 345.

- Harvey 2000, p. 23.

- Harvey 2000, p. 22.

- Adamek 2005, p. 140.

- Rhys Davids, C. A. F. (1912). A Study of the Buddhist Norm. London: T. Butterworth. pp. 148–9.

- Walsh 2007, p. 361.

- Lamotte 1988, p. 72.

- Keyes, Charles F. (1987). "Thai religion" (PDF). In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson Gale. p. 9094. ISBN 978-0-02-865735-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Seeger, Martin (2006). "Die thailändische Wat Phra Thammakai-Bewegung" [The Thai Wat Phra Dhammakaya Movement] (PDF). In Mathes, Klaus-Dieter; Freese, Harald (eds.). Buddhism in the Past and Present (in German). Vol. 9. Asia-Africa Institute, University of Hamburg.

- Mulder 1969, p. 110.

- Findly 2003, pp. 256–7.

- Marston 2006, p. 171.

- Egge 2013, p. 61.

- Mulder 1969, p. 115.

- Schopen 1997, pp. ix–x, 31.

- Namchoom & Lalhmingpuii 2016, p. 52.

- Findly 2003, p. 226.

- Kinnard, Jacob (2006). "Buddhism" (PDF). In Riggs, Thomas (ed.). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices. Vol. 1. Farmington Hills: Thomson Gale. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-7876-6612-5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Kapstein, Maththew T. (2005). "Buddhism: Buddhism in Tibet" (PDF). In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson Gale. p. 1155. ISBN 978-0-02-865735-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Scott 2009, p. 95.

- Walsh 2007, pp. 362–6.

- Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 53–4.

- Scott 2009, p. 126.

- Mulder 1969.

- Fisher 2008, p. 148.

- Swearer 1995, p. 6.

- Scott 2009, p. 101.

- Mulder 1979, p. 127.

- Swearer 1995, p. 22.

- Bao 2005, p. 124.

- Marston 2006, p. 172.

- Appleton 2014, pp. 127, 135–6.

- Walters 2003, pp. 20–2.

- Jory 2002, p. 61.

- Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 54–5.

- Schober 1996, passim..

- Jory 2002, p. 37.

- Aung-Thwin & Aung-Thwin 2013, p. 84.

- Bowie 2017, p. 19.

- Rāhula 1966, pp. 255–6.

- Igunma, Jana (2015). "Meditations on the Foul in Thai Manuscript Art" (PDF). Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Universities. V: 69–70.

- Holt, John C. (2006). "Sri Lanka" (PDF). In Riggs, Thomas (ed.). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices. Vol. 3. Farmington Hills: Thomson Gale. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-7876-6614-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Ledgerwood, Judy (2008), Kent, Alexandra; Chandler, David (eds.), "Buddhist Practice in Rural Kandal Province, 1960 and 2003" (PDF), People of virtue: Reconfiguring religion, power and moral order in Cambodia today, Copenhagen: NIAS, p. 149, ISBN 978-87-7694-036-2

- Swearer, Donald K. (1987). "Buddhist Religious Year" (PDF). In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 2 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson Gale. p. 1306. ISBN 978-0-02-865735-6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Powers, John (2007). Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism (PDF) (2nd ed.). Ithaca, N.Y.: Snow Lion Publications. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-55939-835-0.

- Jory 2002, pp. 63–4.

- Bowie 2017, p. 45.

- Swearer 1995, pp. 19, 22–3.

- Rāhula 1966, p. 285.

- Calkowski 2006, p. 105.

- Reinschmidt, Michael C. (2006). "South Korea" (PDF). In Riggs, Thomas (ed.). Worldmark Encyclopedia of Religious Practices. Vol. 3. Farmington Hills: Thomson Gale. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-7876-6614-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Pommaret, Françoise (2005). "Worship and devotional life: Buddhist devotional life in Tibet" (PDF). In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 14 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson Gale. pp. 9840–1. ISBN 978-0-02-865983-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Reader & Tanabe 1998, p. 200.

- Brokaw 2014, pp. 3–4, 31–2.

- Robinson, Richard H.; Johnson, Willard L. (1977). The Buddhist religion: a historical introduction (4th ed.). Belmont, California: Cengage. p. 215. ISBN 978-0-534-20718-2.

- Bokenkamp, Stephen R. (2005). "Daoism: An overview" (PDF). In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 4 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson Gale. p. 2187. ISBN 978-0-02-865737-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Brokaw 2014, pp. 31–2.

- Brokaw 2014, pp. 3–4.

- Tanabe 2004, p. 533.

- Rotman 2008.

- Spiro 1982, pp. 111–2, 454.

- Lamotte 1988, pp. 430–1.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 140.

- Rāhula 1966, pp. xxii–iii, 254–5.

- Pandita, P., & Berkwitz, S. C. (2007). The History of the Buddha's Relic Shrine: A Translation of the Sinhala Thupavamsa. Oxford University Press. Quoted in: Langer, Rita (2007). Buddhist Rituals of Death and Rebirth: Contemporary Sri Lankan Practice and Its Origins. Routledge. Introduction. ISBN 978-1-134-15872-0.

- Schlieter, Jens (October 2013). "Checking the heavenly 'bank account of karma': cognitive metaphors for karma in Western perception and early Theravāda Buddhism". Religion. 43 (4): 463–86. doi:10.1080/0048721X.2013.765630. S2CID 171027951.

- Schober 1996, p. 205.

- Scott 2009, pp. 30–2, 97.

- Davis, Winston (1987). "Wealth" (PDF). In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 14 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson Gale. p. 9708. ISBN 978-0-02-865983-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Spiro 1982, p. 111.

- Keyes 1983, pp. 18–9.

- Gombrich 2006, pp. 127–8.

- Gombrich 1971, p. 208.

- Gethin 1998, pp. 109–10.

- Buddhism. An Outline of its Teachings and Schools by Schumann, Hans Wolfgang, trans. by Georg Fenerstein, Rider: 1973, p. 92. Cited in "The Notion of Merit in Indian Religions," by Tommi Lehtonen, Asian Philosophy, Vol. 10, No. 3, 2000 pg 193

- Williams 2008, p. 203.

- Keyes 1977, p. 287.

- Nyanatiloka 1980a.

- Marasinghe 2003, p. 472.

- Masefield, Peter (2004). "Ghosts and spirits" (PDF). In Buswell, Robert E. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Vol. 2. New York (u.a.): Macmillan Reference USA, Thomson Gale. pp. 309–10. ISBN 978-0-02-865720-2.

- Gombrich 2006, p. 126.

- Malalasekera 1967, p. 85.

- Gombrich 1971, pp. 209–10.

- Harvey 2012, p. 45.

- Cuevas, Brian J. (2004). "Intermediate state" (PDF). In Buswell, Robert E. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Vol. 2. New York (u.a.): Macmillan Reference USA, Thomson Gale. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-02-865720-2.

- Gombrich 2009, p. 36.

- Harvey 2000, p. 335.

- Bechert 1992, note 34, pp. 99–100.

- Gombrich 1971, p. 204.

- Marasinghe 2003, p. 469.

- Gombrich 1971, p. 216.

- Egge 2013, p. 96.

- Malalasekera 1967, p. 89.

- Anālayo, Bhikkhu (2010). "Saccaka's Challenge–A Study of the Saṃyukta-āgama Parallel to the Cūḷasaccaka-sutta in Relation to the Notion of Merit Transfer" (PDF). Chung-Hwa Buddhist Journal. 23: 60–2. ISSN 1017-7132.

- Gombrich 1971, p. 210.

- Bechert 1992, p. 105.

- Holt 1981, pp. 5–10, 17, 19–20.

- Bechert 1992, pp. 99–100.

- Padma & Barber 2009, p. 116.

- Fogelin, Lars (2006). Archaeology of Early Buddhism. p. 43.

- Basham, A.L. (1981). "The evolution of the concept of the Bodhisattva" (PDF). In Kawamura, Leslie S. (ed.). The Bodhisattva Doctrine in Buddhism. Bibliotheca Indo-Buddhica. Vol. 186 (1 ed.). Sri Satguru Publications. pp. 33, 37. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 April 2017.

- Keyes, Charles F. (1975). "Tug-of-war for merit cremation of a senior monk". Journal of the Siam Society. 63: 54.

- Deegalle, Mahinda (2003). "Preacher as a Poet". In Holt, John Clifford; Kinnard, Jacob N.; Walters, Jonathan S. (eds.). Constituting communities Theravada Buddhism and the religious cultures of South and Southeast Asia. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-7914-5691-0.

- Abe, Masao (1997). "Buddhism in Japan" (PDF). In Carr, Brian; Mahalingam, Indira (eds.). Companion encyclopedia of Asian philosophy. London: Routledge. p. 693. ISBN 978-0-203-01350-2.

- Reynolds, Frank (2006). "Mahāyāna". In Doniger, Wendy; Eliade, Mircea (eds.). Britannica encyclopedia of world religions. Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica. p. 683. ISBN 978-1-59339-491-2.

- Pye & Strong 1987, pp. 5874–5.

- Tuladhar-Douglas, William (2005). "Pūjā: Buddhist Pūjā" (PDF). In Jones, Lindsay (ed.). Encyclopedia of Religion. Vol. 11 (2 ed.). Detroit: Thomson Gale. pp. 7496–7. ISBN 978-0-02-865740-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 March 2017.

- Lamotte 1988, p. 433.

- Thomas 1953, p. 196.

- Skilling 2005, p. 9839.

- Gómez 2002, p. 293.

- Reader & Tanabe 1998, p. 85.

- Salguero 2013, p. 346.

- Scott 2009, pp. 98–102.

- Harvey 2000, pp. 114–5.

- Strong, John S. (2003). "Toward a Theory of Buddhist Queenship" (PDF). In Holt, John Clifford; Kinnard, Jacob N.; Walters, Jonathan S. (eds.). Constituting communities Theravada Buddhism and the religious cultures of South and Southeast Asia. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7914-5691-0.

- Harvey 2000, p. 115.

- Rāhula 1966, p. 256.

- Jory 2002.

- Keyes 1977, p. 288.

- Jory 2002, p. 52.

- Harvey 2000, p. 117.

- Jory 2002, p. 53.

- Aung-Thwin & Aung-Thwin 2013, p. 183.

- Walters 2003, p. 19.

- Holt, John Clifford; Kinnard, Jacob N.; Walters, Jonathan S. (2003). Constituting communities Theravada Buddhism and the religious cultures of South and Southeast Asia (PDF). Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7914-5691-0.

- Jory 2016, pp. 20, 181–2.

- Kleinod, Michael (2015). "Laos". In Athyal, Jesudas M. (ed.). Religion in Southeast Asia: An Encyclopedia of Faiths and Cultures. ABC-CLIO. p. 152. ISBN 978-1-61069-250-2.

- Scott 2009, pp. 90–1.

- Cate & Lefferts 2006, p. 588.

- Marston 2006, p. 169.

- Calkowski 2006, pp. 106–7.

- Scott 2009, pp. 90–1, 126.

- Skilling 2005, p. 9833.

- Cousins, L.S. (1997). "Aspects of Esoteric Southern Buddhism" (PDF). In Connolly, Peter; Hamilton, Sue (eds.). Indian insights: Buddhism, Brahamanism and bhakti. London: Luzac Oriental. p. 188. ISBN 978-1-898942-15-3.

- McCargo, Duncan (2016). Haynes, Jeff (ed.). The politics of Buddhism in Southeast Asia. Religion, Globalization and Political Culture in the Third World. Springer. p. 219. ISBN 978-1-349-27038-5.

- Cousins, L.S. (1996b). Skorupski, T. (ed.). The Origins of Insight Meditation. The Buddhist Forum: Seminar Papers, 1994–1996. London: University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies. p. 39 n.10.

- Harvey 2000, p. 192.

- Cole, Diane. "You'll Never Guess The Most Charitable Nation In The World". NPR. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Basham 1989, pp. 128–9, 133.

- Kent & Chandler 2008, p. 13.

- Bao 2005.

- Bell, Sandra (25 June 2008). "British theravada Buddhism: Otherworldly theories, and the theory of exchange". Journal of Contemporary Religion. 13 (2): 156. doi:10.1080/13537909808580828.

- Heine, Steven; Wright, Dale S. (2008). Zen ritual : studies of Zen theory in practice (PDF). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-19-530467-1.

- Harvey 2000, p. 193.

- Fisher 2008, p. 152.

- Harvey 2000, pp. 193–4.

- Fisher 2008, passim..

- Fuengfusakul 1998, pp. 53, 57; Harvey 2000, pp. 193–194; Walters 2003, p. 3.

- Hanks 1962, p. 1248.

- Nissen, Christine J. (2008). "Buddhist Practice in Rural Kandal Province, 1960 and 2003" (PDF). In Kent, Alexandra; Chandler, David (eds.). People of virtue: Reconfiguring religion, power and moral order in Cambodia today (Reprint ed.). Copenhagen: NIAS. p. 276. ISBN 978-87-7694-036-2.

- Gutschow 2004, p. 18.

- Basham 1989, pp. 127–8.

- Hanks 1962, pp. 1247–8, 1252.

- Keyes 1973, p. 97.

- Findly 2003, pp. 261–2.

- Harvey 2000, pp. 261–2.

- Keyes 1983, p. 269.

- Mulder 1979, p. 117.

- Keyes 1977, pp. 288–90.

- Keyes 1973, pp. 101–2.

- Jory 2002, pp. 45–6.

- Murdoch, John B. (1967). "The 1901–1902" Holy Man's" Rebellion" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 5: 78–86.

- Kent & Chandler 2008, p. 5.

- Basham 1989, pp. 134–5 n.1.

- "A religious revival: Animal spirits". The Economist. Originally from China print edition. 12 September 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Nuwer, Rachel (8 January 2012). "Buddhist Ceremonial Release of Captive Birds May Harm Wildlife". Scientific American. Retrieved 13 October 2016.

- Shiu & Stokes 2008, p. 184.

- Severinghaus, Lucia Liu; Chi, Li (1999). "Prayer animal release in Taiwan". Biological Conservation. 89 (3): 301. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(98)00155-4.

- Shiu & Stokes 2008, p. 186.

- Darlington 2016, 25 min..

- Darlington 2016, 30 min..

- Mahavongtrakul, Melalin (7 October 2019). "Human cruelty for a false belief" (Opinion). Bangkok Post. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Darlington 2016, 29,32–33 min..

- "Religion and Conservation Biology". conbio.org. Society for Conservation Biology. Retrieved 13 October 2016.