Battle of Messines (1917)

The Battle of Messines (7–14 June 1917) was an attack by the British Second Army (General Sir Herbert Plumer), on the Western Front, near the village of Messines (now Mesen) in West Flanders, Belgium, during the First World War.[lower-alpha 1] The Nivelle Offensive in April and May had failed to achieve its more grandiose aims, had led to the demoralisation of French troops and confounded the Anglo-French strategy for 1917. The attack forced the Germans to move reserves to Flanders from the Arras and Aisne fronts, relieving pressure on the French.

| Battle of Messines | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||||

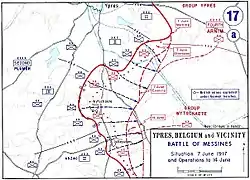

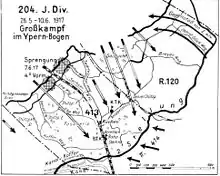

Map of the battle, depicting the front on 7 June and operations until 14 June | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Douglas Haig Herbert Plumer |

Prince Rupprecht Sixt von Armin | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

| Second Army | XIX (2nd Royal Saxon) Corps | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 12 divisions | 5 divisions | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

| 24,562 | 21,886 (21 May to 10 June) – 26,087 (7–14 June) | ||||||||

Messines Ridge Mesen (Messines in French, historically used in English) in the Belgian province of West Flanders | |||||||||

The British tactical objective was to capture the German defences on the ridge, which ran from Ploegsteert Wood (Plugstreet to the British) in the south, through Messines and Wytschaete to Mt Sorrel, depriving the German 4th Army of the high ground. The ridge gave commanding views of the British defences and back areas of Ypres to the north, from which the British intended to conduct the Northern Operation, an advance to Passchendaele Ridge and then the capture of the Belgian coast up to the Dutch frontier. The Second Army had five corps, three for the attack and two on the northern flank not part of the operation; XIV Corps was in General Headquarters reserve. The 4th Army divisions of Group Wytschaete (Gruppe Wijtschate, the IX Reserve Corps headquarters) held the ridge and were later reinforced by a division from Group Ypres (Gruppe Ypern).

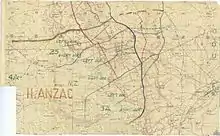

The British attacked with the II Anzac Corps (3rd Australian Division, New Zealand Division and the 25th Division, with the 4th Australian Division in reserve), IX Corps (36th (Ulster), 16th (Irish) and 19th (Western) divisions and the 11th (Northern) Division in reserve), X Corps (41st, 47th (1/2nd London) and 23rd Divisions with the 24th Division in reserve). XIV Corps in reserve (Guards, 1st, 8th and 32nd divisions). The 30th, 55th (West Lancashire), 39th and 38th (Welsh) divisions in II Corps and VIII Corps, guarded the northern flank and made probing attacks on 8 June. Gruppe Wijtschate held the ridge with the 204th, 35th, 2nd, 3rd Bavarian (relieving the 40th Division when the British attack began) and 4th Bavarian divisions, with the 7th Division and 1st Guard Reserve Division as Eingreif (counter-attack) divisions. The 24th Saxon Division, relieved on 5 June, was rushed back when the attack began and the 11th Division, in Gruppe Ypern reserve, arrived on 8 June.[2]

The battle began with the detonation of nineteen mines beneath the German front position, which devastated it and left large craters. A creeping barrage, 700 yd (640 m) deep, began and protected the British troops as they secured the ridge with support from tanks, cavalry patrols and aircraft. The effect of the British mines, barrages and bombardments was improved by advances in artillery survey, flash spotting and centralised control of artillery from the Second Army headquarters. British attacks from 8 to 14 June advanced the front line beyond the former German Sehnenstellung (Chord Position, the Oosttaverne Line to the British). The battle was a prelude to the much larger Third Battle of Ypres, the preliminary bombardment for which began on 11 July 1917.

Background

British plans 1916–1917

In 1916, the British planned to clear the Germans from the Belgian coast to deny them the use of the ports as naval bases. In January, Plumer recommended to Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig the capture of Messines Ridge (part of the southern arc of the Ypres Salient) before an operation to capture the Gheluvelt plateau further north.[3] The highest ground north of the Messines–Wytschaete ridge lies on the Menin road, between Hooge and Veldhoek, 1.5 mi (2.4 km) from Gheluvelt, at the west end of the main Ypres ridge, which runs from Ypres, east to Broodseinde and then north-east to Passchendaele, Westroosebeek and Staden. The British called it the Gheluvelt Plateau or Menin Ridge. Roads and tracks converged on the Menin road at this point (Clapham Junction to the British). The east end of the Gheluvelt plateau was on the west side of Polygon Wood.[4] A flat spur either side of the Menin road ran about 3.5 mi (5.6 km) south-eastwards towards Kruiseecke and was about 1 mi (1.6 km) wide at Veldhoek, with a depression on the west side through which the Bassevillebeek flowed southwards and another on the east side, through which the Reutelbeek also flowed south. The spur widened to almost 2 mi (3.2 km) between Veldhoek and Gheluvelt.[5]

A Flanders campaign was postponed because of the Battle of Verdun in 1916 and the demands of the Battle of the Somme. When it became apparent that the Second Battle of the Aisne (the main part of the Nivelle Offensive, 16 April to 9 May 1917) had failed to achieve its most ambitious objectives, Haig instructed the Second Army to capture the Messines–Wytschaete Ridge as soon as possible.[6] British operations in Flanders would relieve pressure on the French Armies on the Aisne, where demoralisation amid the failure of the Nivelle Offensive had led to mutinies. The capture of Messines Ridge would give the British control of the tactically important ground on the southern flank of the Ypres Salient, shorten the front and deprive the Germans of observation over British positions further north. The British would gain observation of the southern slope of Menin Ridge at the west end of the Gheluvelt plateau, ready for the Northern Operation.[7]

The front line around Ypres had changed little since the end of the Second Battle of Ypres (22 April – 25 May 1915).[8] The British held the city and the Germans held the high ground of the Messines–Wytschaete Ridge to the south, the lower ridges to the east and the flat ground to the north.[9] The term high ground is relative; Passchendaele is on a ridge about 70 ft (21 m) above the surrounding plains. The Gheluvelt plateau is about 100 ft (30 m) above the vicinity and Wytschaete is about 150 ft (46 m) higher than the plain; control of the ground was vital for artillery observation.[10] The Ypres front was a salient bulging into the German lines and was overlooked by German artillery observers on the higher ground. The British had little ground observation of the German rear areas and valleys east of the ridges.[11]

The ridges run north and east from Messines, 264 ft (80 m) above sea-level at its highest point, past Clapham Junction at the west end of the Gheluvelt plateau, 2.5 mi (4.0 km) from Ypres at 213 ft (65 m) and Gheluvelt, above 164 ft (50 m), to Passchendaele 5.5 mi (8.9 km) from Ypres at 164 ft (50 m), declining from there into the plain further north. Gradients vary from negligible to 1:60 at Hooge and 1:33 at Zonnebeke.[12] Underneath the soil is London clay, sand and silt. According to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission criteria of "sand", "sandy soils" and "well-balanced soils", Messines Ridge is "well-balanced soil", drained by many streams, canals and ditches, which needed regular maintenance.[13] Since the First Battle of Ypres in 1914, much of the drainage in the area had been destroyed by artillery-fire, although some repairs had been achieved by army Land Drainage Companies brought from England. The area was considered by the British to be drier than Loos, Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée (Givenchy) and Plugstreet (Ploegsteert) Wood further south.[14]

Prelude

British preparations

The Second Army centralised its artillery and devised a plan of great sophistication, following the precedent set at the Battle of Arras in April. The use of field survey, gun calibration, weather data and a new and highly accurate 1:10,000 scale map, much improved artillery accuracy.[15] Systematic target-finding was established by the use of new sound-ranging equipment, better organisation of flash-spotting and the communication of results through the Army Report Centre at Locre Château. Counter-battery artillery bombardments increased from twelve in the week ending 19 April, to 438 in the last ten days before the attack. A survey of captured ground after the battle found that 90 per cent of the German artillery positions had been plotted. The 2nd Field Survey Company also assisted mining companies by establishing the positions of objectives within the German lines, using intersection and a special series of aerial photographs. The company surveyed advanced artillery positions for guns to be moved forward to them and open fire as soon as they arrived.[16]

The British had begun a mining offensive against the Wijtschatebogen (Wytschaete position) in 1916. Sub-surface conditions were especially complex and separate ground water tables made mining difficult. Two military geologists assisted the miners from March 1916, including Edgeworth David, who planned the system of mines.[17] Sappers dug the tunnels into a layer of blue clay 80–120 ft (24–37 m) underground, then drifted galleries for 5,964 yd (3.389 mi; 5.453 km) to points deep underneath the front position of Gruppe Wijtschate, despite German counter-mining.[18] German tunnellers came close to several British mine chambers, found the mine at La Petite Douve Farm and wrecked the chamber with a camouflet.[19] The British diverted the attention of German miners from their deepest galleries by making many secondary attacks in the upper levels.[20] Co-ordinated by tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers, Canadian, Australian, New Zealand and British miners laid 26 mines with 447 long tons (454 t) of ammonal explosive.[21]

Two mines were laid at Hill 60 on the northern flank, one at St Eloi, three at Hollandscheschuur, two at Petit Bois, one each at Maedelstede Farm, Peckham House and Spanbroekmolen, four at Kruisstraat, one at Ontario Farm and two each at trenches 127 and 122 on the southern flank.[22] One of the largest of the mines was at Spanbroekmolen; Lone Tree Crater formed by the blast of 91,000 lb (41,277 kg) of ammonal in a chamber at the end of a gallery 1,710 ft (0.324 mi) long, 88 ft (27 m) below ground was 250 ft (76 m) in diameter and 40 ft (12 m) deep.[23] The British knew of the importance the Germans placed on holding the Wijtschate salient, after a captured corps order from Gruppe Wijtschate stating "that the salient be held at all costs" was received by Haig on 1 June.[24] In the week before the attack, 2,230 guns and howitzers bombarded the German trenches, cut wire, destroyed strongpoints and conducted counter-battery fire against 630 German artillery pieces, using 3,561,530 shells. The 4th Army artillery consisted of 236 field guns, 108 field howitzers, fifty-four 100–130 mm guns, twenty-four 150 mm guns, 174 medium howitzers, 40 heavy howitzers and four heavy 210 mm and 240 mm guns.[25]

In May, the 4th Australian Division, 11th (Northern) Division and the 24th Division were transferred from Arras as reserve divisions for the Second Army corps in the attack on Messines Ridge. Seventy-two of the new Mark IV tanks also arrived in May and were hidden south-west of Ypres.[26] British aircraft began to move north from the Arras front, the total rising to about 300 operational aircraft in the II Brigade RFC (Second Army) area.[27][lower-alpha 2] The mass of artillery to be used in the attack was supported by many artillery-observation and photographic reconnaissance aircraft, in the corps squadrons which had been increased from twelve to eighteen aircraft each. Strict enforcement of wireless procedure allowed a reduction of the minimum distance between observation aircraft from 1,000 yd (910 m) at Arras in April to 400 yd (370 m) at Messines, without mutual wireless interference.[27] Wire-cutting bombardments began on 21 May and two days were added to the bombardment for more counter-battery fire. The main bombardment began on 31 May, with only one day of poor weather before the attack. Two flights of each observation squadron concentrated on counter-battery observation and one became a bombardment flight, working with particular artillery bombardment groups for wire cutting and trench-destruction; these flights were to become contact-patrols to observe the positions of British troops once the assault began. The attack barrage was rehearsed on 3 June to allow British air observers to plot masked German batteries, which mainly remained hidden but many minor flaws in the British barrage were reported. A repeat performance on 5 June, induced a larger number of hidden German batteries to reveal themselves.[29]

The 25th Division made its preparations on a front from the Wulverghem–Messines road to the Wulverghem–Wytschaete road, facing 1,200 yd (1,100 m) of the German front line, which tapered to the final objective, 700 yd (640 m) wide, at the near crest of the ridge, 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) distant, behind nine German defensive lines. The advance would begin up a short rise to the near edge of the Steenbeek Valley, then up the steep rise from the valley floor between Hell and Sloping Roof farms to Four Huns, Chest and Middle farms on the main ridge, with Lumm Farm on the left flank of the objective. Artillery emplacements for the 25th divisional artillery and 112th Army Field Brigade were built and the Guards Division field artillery was placed in concealed forward positions. Road making and the construction of dugouts and communication trenches took place first between 12 and 30 April and then between 11 May and 6 June. In three hours, an assembly trench was dug 150 yd (140 m) from the German front line on the night of 30/31 May, complete with communication trenches and barbed wire. Bridges and ladders were delivered in the two days before the attack. 13,000 yd (7.4 mi; 12 km) of telephone cable was dug in at least 7 ft (2.1 m) deep, which withstood fifty German artillery hits before the British attack.[30]

Large numbers of posts for machine-guns to fire an overhead barrage were built and protective pits were dug for mules, each of which was to carry 2,000 rounds of ammunition to advanced troops.[31] (Machine-guns were fired like artillery, over the heads of the advancing infantry. The bullets of an overhead barrage came down ahead of the attacking troops on German-held areas, forcing the garrison under cover.) Three field companies of engineers with a pioneer battalion were kept in reserve, to follow up the attacking infantry, rebuild roads and work on defensive positions as ground was consolidated.[32] The divisional artillery devised a creeping and standing barrage plan and time-table, tailored to the estimated rates of advance of the infantry. The standing barrage lifts were to keep all trenches within 1,500 yd (1,400 m) of the infantry under continuous fire. The 4.5-inch howitzer, 6-inch howitzer and 8-inch howitzers involved, were to change targets only when infantry got within 300 yd (270 m). The 18-pounder field gun standing barrages would then jump over the creeping barrages to the next series of objectives. The concealed guns of the Guards Division field artillery were to join the creeping barrage for the advance at 4:50 a.m. and at 7:00 a.m. the 112th Army Field Brigade was to advance to the old front line, to be ready for an anticipated German counter-attack by 11:00 a.m [33]

The 47th (1/2nd London) Division planned to attack with two brigades, each reinforced by a battalion from the reserve brigade, along either side of the Ypres–Comines Canal. Large numbers of machine-guns were organised to fire offensive and defensive barrages and signal detachments were organised to advance with the infantry. An observation balloon was reserved for messages by signal lamp from the front line, as insurance against the failure of telephone lines and message-runners. The divisional trench mortar batteries were to bombard the German front line opposite the 142nd Brigade, where it was too close for the artillery to shell without endangering British troops.[34] Wire-cutting began in mid-May, against considerable local retaliation by German artillery. At the end of May the two attacking brigades went to Steenvoorde to train on practice courses built to resemble the German positions, using air reconnaissance photographs to mark the positions of machine-gun posts and hidden barbed wire. Divisional intelligence summaries were used to plan the capture of German company and battalion headquarters. The 140th Brigade, with four tanks attached, was to occupy White Château and the adjacent part of Damstrasse, while the 142nd Brigade attacked the spoil heaps and the canal bank to the left. On 1 June, the British artillery began the intense stage of the preparatory bombardment for trench-destruction and wire cutting; the two attacking brigades assembled for the attack from 4 to 6 June.[35]

British fighter aircraft tried to prevent German artillery-observation aircraft from operating by dominating the air from the British front line to the German balloon line, about 10,000 yd (5.7 mi; 9.1 km) beyond. Better aircraft like the Bristol Fighter, S.E.5a and the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) Sopwith Triplane had entered service since Arras and matched the performance of German Albatros D.III and Halberstadt D.II fighters. For the week before the attack, the barrage line was patrolled all day by fighters at 15,000 ft (4,600 m) with more aircraft at 12,000 ft (3,700 m) in the centre of the attack front. No British corps aircraft were shot down by German aircraft until 7 June, when 29 corps aircraft were able to direct artillery fire simultaneously over the three attacking corps.[36] Behind the barrage line lay a second line of defence, which used wireless interception to take bearings on German artillery-observation aircraft to guide British aircraft into areas where German flights were most frequent. By June 1917, each British army had a control post of two aeroplane compass stations and an aeroplane intercepting station, linked by telephone to the army wing headquarters, fighter squadrons, the anti-aircraft commander and the corps heavy artillery headquarters.[37]

The new anti-aircraft communication links allowed areas threatened by German bombardment to be warned, German artillery spotting aircraft to be attacked and German artillery batteries to be fired on when they revealed themselves. From 1 to 7 June, the II Brigade RFC had 47 calls from wireless interception, shot down one German aircraft, damaged seven and stopped 22 German artillery bombardments.[38] Normal offensive patrols continued beyond the barrage line out to a line from Ypres to Roulers and Menin, where large formations of British and German aircraft clashed in long dogfights, once German air reinforcements began operating in the area. Longer-range bombing and reconnaissance flights concentrated on German-occupied airfields and railway stations and the night bombing specialists of 100 Squadron attacked trains around Lille, Courtrai, Roulers and Comines.[39] Two squadrons were reserved for close air support on the battlefield and low attacks on German airfields.[40]

Plan

.jpg.webp)

The British planned to advance on a 17,000 yd (9.7 mi; 16 km) front, from St Yves to Mt Sorrel, eastwards to the Oosttaverne line, a maximum depth of 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km).[41] Three intermediate objectives, originally to be reached a day at a time, became halts, where fresh infantry would leap-frog through to gain the ridge in one day. In the afternoon a further advance down the ridge was to be made.[42] The attack was to be conducted by three corps of the Second Army (General Sir Herbert Plumer). II Anzac Corps in the south-east was to advance 800 yd (730 m), IX Corps in the centre was to attack on a 5,000 yd (2.8 mi; 4.6 km) front, which would taper to 2,000 yd (1.1 mi; 1.8 km) at the summit and X Corps in the north had an attack front 1,200 yd (1,100 m) wide.[24] The corps planned their attacks under the supervision of the army commander, using analyses of the Somme operations of 1916 and successful features of the attack at Arras on 9 April as guides. Great care was taken in the planning of counter-battery fire, the artillery barrage time-table and machine-gun barrages.[43][lower-alpha 3]

German artillery positions and the second (Höhenstellung) (Contour Position) position were not visible to British ground observers. For observation over the rear slopes of the ridge, 300 aircraft were concentrated in II Brigade RFC and eight balloons of II Kite Balloon Wing were placed 3,000–5,000 ft (910–1,520 m) behind the British front line. The Second Army artillery commander, Major-General George Franks, co-ordinated the corps artillery plans, particularly the heavy artillery arrangements to suppress German artillery, which were devised by the corps and divisional artillery commanders. The Second Army Report Centre at Locre Château was linked by buried cable to each corps report centre, corps heavy artillery headquarters, divisional artillery headquarters, RFC squadrons, balloon headquarters, survey stations and wireless stations.[46]

Responsibility for counter-battery fire was given to a counter-battery staff officer with a small staff, who concentrated exclusively on the defeat of the German artillery. A conference was held each evening by the counter-battery staffs of divisions and corps, methodically to collate the day's reports from observation aircraft and balloons, field survey companies, sound ranging sections and forward observation officers. Each corps had a counter-battery area, which was divided into zones and allotted to heavy artillery groups. Each heavy artillery group headquarters divided their zones into map squares, which were allotted to artillery batteries, to be ready swiftly to open fire on them.[46]

The attacking corps organised their heavy artillery within the army plan according to local conditions. II Anzac Corps created four counter-battery groups, each with one heavy artillery group and IX Corps arranged four similar groups and five bombardment groups, one for each of its three divisions and two (with the heaviest howitzers) in reserve, under the control of the corps heavy artillery commander. A Heavy Artillery Group Commander was attached to each divisional artillery headquarters, to command the heavy artillery once the infantry attack began. Field artillery arrangements within corps also varied, in IX Corps groups and sub-groups were formed so that infantry brigades had an artillery liaison officer and two sub-groups, one with six 18-pounder batteries and one with six 4.5-inch howitzer batteries. Surplus field artillery brigade headquarters planned forward moves for the guns and were kept ready to replace casualties.[46] It was expected that much of the artillery would need to switch rapidly from the bombardment plan to engage counter-attacking German infantry. It was planned that the Forward Observation Officers of the divisions in the first attack onto the ridge would control the artillery which had remained in place and the reserve divisions advancing down the far slope to the Oosttaverne line would control the artillery hidden close to the front line and the artillery which advanced into no-man's-land.[47]

Franks planned to neutralise German guns within 9,000 yd (5.1 mi; 8.2 km) of the attack front. On the flanks of the British attack front of 17,000 yd (9.7 mi; 16 km), 169 German guns had been located, for which 42 British guns (25 per cent of the German total) were set aside. The 299 German guns in the path of the attack were each to be engaged by a British gun, a formula which required 341 British guns and howitzers to be reserved for counter-battery fire. Every 45 yd (41 m) of front had a medium or heavy howitzer for bombardment, which required 378 guns, with 38 super-heavy guns and howitzers (five per cent) deployed with the field artillery that was due to fire the creeping and standing barrages. Franks devised a bombardment timetable and added arrangements for a massed machine-gun barrage. The 756 medium and heavy guns and howitzers were organised in forty groups and the 1,510 field guns and howitzers in sixty-four field artillery brigades within the attacking divisions and thirty-three Army field artillery brigades, divided among the three attacking corps; 144,000 long tons (146,311 t) of ammunition was delivered, 1,000 shells for each 18-pounder, 750 shells per 4.5-inch howitzer, 500 rounds for each medium and heavy piece and another 120,000 gas and 60,000 smoke shells for the 18-pounder field guns.[48]

.jpg.webp)

Two-thirds of the 18-pounders were to fire a creeping barrage of shrapnel immediately ahead of the advance, while the remainder of the field guns and 4.5-inch howitzers were to fire a standing barrage, 700 yd (640 m) further ahead on German positions, lifting to the next target when the infantry came within 400 yd (370 m) of the barrage. Each division was given four extra batteries of field artillery, which could be withdrawn from the barrage at the divisional commander's discretion to engage local targets.[49] The field batteries of the three reserve divisions were placed in camouflaged positions close to the British front line. As each objective was taken by the infantry, the creeping barrage was to pause 150–300 yd (140–270 m) ahead and become a standing barrage while the infantry consolidated. During this time the pace of fire was to slacken to one round per-gun per-minute, allowing the gun-crews a respite, before resuming full intensity as the barrage moved on. The heavy and super-heavy artillery was to fire on German artillery positions and rear areas and 700 machine-guns were to fire a barrage over the heads of the advancing troops.[50]

At 03:00 a.m. the mines were to be detonated, followed by the attack of nine divisions onto the ridge.[51] The blue line (first objective) was to be occupied by zero + 1:40 hours followed by a two-hour pause. At zero + 3:40 hours the advance to the black line (second objective) would begin and consolidation was to start by zero + 5 hours. Fresh troops from the unengaged brigades of the attacking divisions or from the reserve divisions would then pass through, to attack the Oosttaverne line at zero + 10 hours. As soon as the black line was captured, all guns were to bombard the Oosttaverne line, conduct counter-battery fire and place a standing barrage beyond the black line. All operational tanks were to join with the 24 held in reserve, to support the infantry advance to the Oosttaverne line.[52]

German preparations

The Messines defences were on a forward slope and could be overlooked from Haubourdin Hill (Hill 63), the south end of the Douve Valley and Kemmel Hill, 5,000 yd (2.8 mi; 4.6 km) west of Wijtschate, an arrangement which the experience of 1916 showed to be obsolete.[lower-alpha 4] A new line, incorporating the revised principles of defence derived from the experience of the Battle of the Somme, known as the Flandernstellung, began in February 1917. The first section began 6 mi (9.7 km) behind Messines Ridge, running north from the Lys to Linselles then Werviq and Beselare, where the nearest areas giving good artillery observation to the west were found.[53] In April, Field Marshal Crown Prince Rupprecht and his chief of staff, Generalleutnant (Lieutenant-General) Hermann von Kuhl, favoured withdrawal to the Warneton (third) line, before a British attack. The local divisional commanders objected, due to their belief that counter-mining had neutralised the British underground threat and the inadequacy of the Warneton line. The convex eastern slope limited artillery observation and the Ypres–Comines canal and the river Lys restricted the space below the ridge where infantry could manoeuvre for counter-attacks. British observation from the ridge would make the ground to the east untenable as far as the Flandernstellung 6 mi (9.7 km) beyond. A withdrawal to the Flandernstellung would endanger the southern slopes of Menin Ridge, the most important area of the Flandernstellung. Rupprecht re-examined the Warneton (third) line and the extra Sehnenstellung between the Warneton Line and the Höhenstellung (Contour Position) and dropped the withdrawal proposal.[54]

Gruppe Wijtschate of the 4th Army, with three divisions under the command of the headquarters of XIX Corps (General Maximilian von Laffert), held the ridge and was reinforced with the 24th Division in early May. The 35th and 3rd Bavarian divisions were brought up as Eingreif divisions and Gruppe Wijtschate was substantially reinforced with artillery, ammunition and aircraft.[55] The vulnerability of the northern end of Messines Ridge, where it met the Menin Ridge, led to the German command limiting the frontage of the 204th (Württemberg) Division to 2,600 yd (1.5 mi; 2.4 km). The 24th Division to the south held 2,800 yd (1.6 mi; 2.6 km) and the 2nd Division at Wijtschate held 4,000 yd (2.3 mi; 3.7 km). In the south-east, 4,800 yd (2.7 mi; 4.4 km) of the front line either side of the river Douve, was defended by the 40th Division.[56] The front-line was lightly held, with fortifications distributed up to 0.5 mi (0.80 km) behind the front line.[57] At the end of May, British artillery fire was so damaging that the 24th and 40th divisions were relieved by the 35th and 3rd Bavarian (Eingreif) divisions, which were replaced by the 7th and 1st Guard Reserve divisions in early June; relief of the 2nd Division was promised for 7/8 June.[58]

The German front line regiments held areas 700–1,200 yd (640–1,100 m) wide with one (Kampf) battalion forward, one (Bereitschaft) battalion in support and the third in reserve 3–4 mi (4.8–6.4 km) back. The Kampf battalion usually had three companies in the front system (which had three lines of breastworks called "Ia", "Ib" and "Ic") and one in the Sonne (intermediate) line (with a company of the support battalion, available for immediate counter-attack) between the front system and the Höhenstellung on the ridge crest. The other three companies of the support battalion sheltered in the Höhenstellung. About 32 machine-gun posts per regimental sector were dispersed around the defensive zone. The German defence was intended to be mobile and Stosstruppen in "Ic" the third breastwork had to conduct immediate counter-attacks to recapture "Ia" and "Ib". If they had to fall back, the support battalions would advance to restore the front system, except at Spanbroekmolen Hill, which due to its importance was to be held at all costs (unbedingtes Halten).[59]

On 8 May, the British preliminary bombardment began and on 23 May became much heavier. The breastworks of the front defences were demolished and concrete shelters on both sides of the ridge were systematically destroyed. Air superiority allowed the British artillery observation aircraft to cruise over the German defences, despite the efforts of Jagdgeschwader 1 (the Richthofen Circus). On 26 May, the German front garrisons were ordered to move forward 50 yd (46 m) into shell-holes in no-man's-land at dawn and return to their shelters at night. When the shelters were destroyed, shell-hole positions were made permanent, as were those of the companies further back. Troops in the Höhenstellung were withdrawn behind the ridge and by the end of May, the front battalions changed every two days instead of every five, due to the effect of the British bombardment.[60]

Some German troops on the ridge were convinced of the mine danger and their morale was depressed further by the statement of a prisoner taken on 6 June, that the attack would be synchronised with mine explosions.[61] On 1 June, the British bombardment became more intense and nearly every German defensive position on the forward slope was obliterated. The Luftstreitkräfte (German air service) effort reached its maximum on 4 and 5 June, when German aircraft observed 74 counter-battery shoots and wireless interception by the British showed 62 German aircraft, escorted by up to seven fighters each, directing artillery fire against the Second Army.[62] British air observation on the reverse slope was less effective than in the foreground but the villages of Mesen and Wijtschate were demolished, as were much of the Höhenstellung and Sehnenstellung, although many pill boxes survived. Long-range fire on Comines, Warneton, Wervicq and villages, road junctions, railways and bridges caused much damage and a number of ammunition dumps were destroyed.[63]

Battle

Second Army

Fine weather was forecast for 4 June, with perhaps a morning haze (between 15 May and 9 June the weather was fair or fine except for 16, 17 and 29 May, when it was very bad).[64] Zero Day was fixed for 7 June, with zero hour at 3:10 a.m., when it was expected that a man could be seen from the west at 100 yd (91 m). There was a thunderstorm in the evening of 6 June but by midnight the sky had cleared and at 2:00 a.m., British aircraft cruised over the German lines to camouflage the sound of tanks as they drove to their starting points. By 3:00 a.m., the attacking troops had reached their jumping-off positions unnoticed, except for some in the II Anzac Corps area.[65]

Routine British artillery night firing stopped around half an hour before dawn and birdsong could be heard. At 3:10 a.m. the mines began to detonate.[65][lower-alpha 5] After the explosions, the British artillery began to fire at maximum rate. A creeping barrage in three belts 700 yd (640 m) deep began and counter-battery groups bombarded all known German artillery positions with gas shell. The nine attacking divisions and the three in reserve began their advance as the German artillery reply came scattered and late, falling on British assembly trenches after they had been vacated.[67]

First objective (blue line)

The II Anzac Corps objective was the southern part of the ridge and Messines village. The 3rd Australian Division on the right, had been disorganised by a German gas bombardment on Ploegsteert (Plugstreet to the British) Wood around midnight, which caused 500 casualties during the approach march but the attack between St Yves and the river Douve began on time. The 9th and 10th Brigades benefitted from four mine explosions at Trenches 122 and 127, which were seven seconds early and left craters 200 ft (61 m) wide and 20 ft (6.1 m) deep. The craters disrupted the Australian attack formation, some infantry lines merging into a wave before reforming as they advanced. The New Zealand Division approached over Hill 63 and avoided the German gas bombardment. The two attacking brigades crossed the dry riverbed of the Steenebeke and took the German front line, despite the mine at La Petite Douve Farm not being fired and then advanced towards Messines village. On the left of the corps, the 25th Division began its advance 600 yd (550 m) further back than the New Zealand Division but quickly caught up, helped by the mine at Ontario Farm.[68]

On the right of IX Corps, the 36th (Ulster) Division attack on the front of the 107th Brigade, was supported by three mines at Kruisstraat and the big mine at Spanbroekmolen, 800 yd (730 m) further north. The 109th Brigade on the left was helped by a mine at Peckham House and the devastated area was crossed without resistance, as German survivors in the area had been stunned by the mine explosions. The 16th (Irish) Division attacked between Maedelstede Farm and the Vierstraat–Wytschaete road. The mines at Maedelstede and the two at Petit Bois devastated the defence; the mines at Petit Bois on the left were about 12 seconds late and knocked over some of the advancing British infantry. On the left of IX Corps, the 19th Division, north of the Vierstraat–Wytschaete road, attacked with two brigades into the remains of Grand Bois and Bois Quarante. Three mine explosions at Hollandscheschuur allowed the infantry to take a dangerous salient at Nag's Nose, as German survivors surrendered or retreated.[69]

X Corps had a relatively short advance of 700 yd (640 m) to the crest and another 600 yd (550 m) across the summit, which would uncover the German defences further north on the southern slope of the Gheluvelt plateau and the ground back to Zandvoorde. The German defences had been strengthened and had about double the normal infantry garrison. The German artillery concentration around Zandvoorde made a British attack in the area highly vulnerable but the British counter-battery effort suppressed the German artillery, its replies being late and ragged. On the night of 6/7 June, gaps were cut in the British wire to allow the troops to assemble in no-man's-land, ready to attack at 3:10 a.m.[35]

The 41st Division attacked with two brigades past a mine under the St Eloi salient, finding the main obstacle to be wreckage caused by the explosion. The 47th and 23rd divisions formed the left defensive flank of the attack, advancing onto the ridge around the Ypres–Comines canal and railway, past the mines at Caterpillar and Hill 60. The cuttings of the canal and railway were a warren of German dug-outs but the 47th Division, advancing close up to the creeping barrage, crossed the 300 yd (270 m) of the German front position in 15 minutes, German infantry surrendering along the way. Soft ground in the valley south of Mt Sorrel, led the two infantry brigades of the 23rd Division to advance on either side up to the near crest of the ridge, arriving while the ground still shook from the mines at Hill 60.[70]

In the areas of the mine explosions, the British infantry found dead, wounded and stunned German soldiers. The attackers swept through the gaps in the German defences as Germans further back hurriedly withdrew. About 80,000 British troops advanced up the slope, the creeping bombardment throwing up lots of smoke and dust, which blocked the view of the German defenders. The barrage moved at 100 yd (91 m) in two minutes, which allowed the leading troops to rush or outflank German strong points and machine-gun nests. Where the Germans were able to resist, they were engaged with rifle-grenades, Lewis Guns and trench mortars, while riflemen and bombers worked behind them.[71]

Pillbox fighting tactics had been a great success at the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April and in training for the attack at Messines, the same methods were adopted along with emphasis on mopping-up captured ground, to ensure that bypassed German troops could not engage advancing troops from behind. In the smoke and dust, direction was kept by compass and the German forward zone was easily overrun in the 35 minutes allotted, as was the Sonne line, half way to the German Höhenstellung on the ridge. The two supporting battalions of the attacking brigades leap-frogged through, to advance to the second objective on the near crest of the ridge 500–800 yd (460–730 m) further on. The accuracy of the British barrage was maintained and local German counter-attack attempts were stifled. As the infantry approached the German second line, resistance increased.[71]

Second objective (black line)

In the II Anzac Corps area, the 3rd Australian Division consolidated the southern defensive flank of the attack, digging-in astride the river Douve with its right in the new craters at Trench 122, defeating several hasty German counter-attacks; the left flank of the division was anchored by a captured German strongpoint. The New Zealand Division attacked Messines village, the southern bastion of the German defences on the ridge. The village had been fortified with a line of trenches around the outskirts and an inner defence zone comprising five pillboxes and all the house cellars, which had been converted into shellproof dugouts. Two machine-gun posts on the edge of the village were rushed but fire from Swayne's Farm 400 yd (370 m) north held up the advance, until a tank drove through it and caused 30 German troops to surrender. The New Zealanders penetrated the outer trenches behind the creeping barrage, which slowed to 100 yd (91 m) in 11 minutes. The German garrison defended the village with great determination, before surrendering when the garrison commander was captured. The 25th Division took the Messines–Wytschaete road on the ridge, north of the New Zealand Division with little opposition except at Hell Farm, which was eventually overrun.[72]

In the IX Corps area, the 36th (Ulster) Division captured the wreckage of two woods and Bogaert Farm in between, finding that the artillery fire had cut the masses of barbed wire and destroyed many strongpoints. Further north, the 16th (Irish) and 19th divisions advanced through the remains of Wytschaete wood and Grand Bois, which had been hit by a 2,000 oil drum Livens Projector bombardment on the night of 3/4 June and by standing barrages on all the known German positions in the woods.[73][lower-alpha 6] A German force at L'Hospice held out despite being by-passed, until 6:48 a.m. and the objective was reached just after 5:00 a.m.[73]

German positions at Dammstrasse, which ran from the St Eloi road to White Château, in the X Corps area, fell to the 41st Division after a long fight. White Château was attacked by the 47th Division as it advanced to the first objective, covered by smoke and Thermite shells fired on the German positions further to the north, along the Comines Canal. The German garrison fought hard and repulsed two attacks, before surrendering after a trench-mortar bombardment at 7:50 a.m. The northern defensive flank was maintained by the 23rd Division, with an advance of 300 yd (270 m) in twenty minutes. A German force at the head of the Zwarteleen re-entrant, south of Mt Sorrel where the two attacking brigades met, held out until forced to surrender by volleys of rifle-grenades.[76]

Just after 5:00 a.m. the British second intermediate objective, the first trench of the Höhenstellung, on the near crest of the ridge, had been taken. German documents gleaned from the battlefield showed that they expected the forward crest of the ridge to be held until the Eingreif divisions arrived to counter-attack.[77] The next objective was the rear trench of the Höhenstellung and the rear crest of the ridge, 400–500 yd (370–460 m) away. There was a pause of two hours, for fresh battalions to move forward and the captured ground to be consolidated. About 300 yd (270 m) beyond the forward positions, a protective bombardment by 18-pounders swept back and forth, while the heavier artillery stood ready to respond with SOS barrages. Pack animals and men carrying Yukon packs, brought supplies into the captured ground and engineers supervised the digging and wiring of strongpoints. At 7:00 a.m. the protective bombardment increased in intensity and began to creep forward again, moving at 100 yd (91 m) in three minutes, as some divisions used battalions from their third brigade and other divisions those that had attacked earlier. Most of the tanks still operational were outstripped but some caught up the infantry.[78]

Fresh battalions of the New Zealand Division leap-frogged through the battalions which had attacked earlier, advancing either side of Messines, where some German posts still held out. A German artillery headquarters at Blauwen Molen (blue windmill), 500 yd (460 m) beyond Messines, was captured and a tank broke into a strong point at Fanny's Farm, causing a hundred Germans to surrender. The reserve brigade of the 25th Division continued the advance to the north except at Lumm Farm, which was eventually taken with assistance from the right flank troops of the 36th (Ulster) Division. Helped by two tanks, the rest of the 36th (Ulster) Division advanced to the right of Wytschaete village and captured a German battalion headquarters. Wytschaete had been fortified like Messines but special bombardments fired on 3 June had demolished the village. Two battalions of the 16th (Irish) Division overran the German survivors and on the left, the reserve brigade of the 19th Division took the area from Wytschaete village to Oosttaverne Wood with little resistance.[79]

X Corps had greater difficulty reaching some of its final objectives; the loss of White Château disorganised the German defenders adjacent to the south. The 41st Division easily crossed the summit and reached the rear slope of the ridge 500 yd (460 m) away, which overlooked the eastern slope and Roozebeke valley, taking many prisoners at Denys and Ravine woods. North of the canal, the 47th Division had to capture a spoil heap 400 yd (370 m) long, where several German machine-gun nests had been dug in. The British attacks established a footing on the heap at great cost, due to machine-gun fire from the spoil heap and others in Battle Wood further north. At 9:00 a.m. the infantry withdrew to allow the area to be bombarded from 2:30 to 6:55 p.m. for an attack by a reserve battalion at 7:00 p.m.[80] The 23rd Division had many casualties caused by flanking machine-gun fire from the spoil heap while clearing Battle Wood, which took until the evening.[81]

In the centre of the attack, a company from each battalion advanced behind the barrage, to an observation line several hundred yards down the east slope of the ridge, at 8:40 a.m. assisted by eight tanks and patrols of cavalry. Most German troops encountered surrendered quickly, except at Leg Copse and Oosttaverne Wood where they offered slight resistance. British aircraft added to German difficulties, with low-level machine-gun attacks. The second objective (the observation line) from Bethlehem Farm to south of Messines, Despagne Farm and Oosttaverne Wood, was reached with few casualties. Ground markers were put out for the three divisions due to attack in the afternoon and the area consolidated.[82] The defensive frontages of the British units on the ridge had been based on an assumption that casualties in the advance to the first intermediate objective (blue line) would be 50 per cent and in the advance to the ridge (black line) would be 60 per cent. There were far fewer British casualties than anticipated, which caused congestion on the ridge, where the attacking troops suffered considerable casualties from German long-range machine-gun and artillery fire. The British planners expected that the two German Eingreif divisions behind the ridge would begin organised counter-attacks at about 11:00 a.m., and arranged for a long pause in the advance down the eastern slope, thereby enabling an attack from consolidated defensive positions, rather than an encounter in the open while the British were still advancing. The masked batteries of the three reserve divisions were used to add to the protective barrage in front of the infantry but no Germans could be seen.[83]

Final objective (Oosttaverne line)

A pause of five hours was considered necessary to defeat the German Eingreif divisions, before resuming the advance on the Oosttaverne (Sehnen) line. The pause was extended by two hours to 3:10 p.m., after Plumer received reports on the state of the ground. More artillery joined the masked batteries close to the front line and others moved as far into no-man's-land as the terrain allowed. On the nearside of the ridge, 146 machine-guns were prepared to fire an overhead barrage, and each division placed sixteen more guns in the observation line on the eastern slope. The 24 tanks in reserve began to advance at 10:30 a.m. to join II Anzac Corps and IX Corps on the flanks. Surviving tanks of the morning attack in X Corps, were to join in from Damm and Denys woods.[84]

The 4th Australian Division continued the attack on the II Anzac Corps front, the right hand brigade reaching the assembly areas by 11:30 a.m., before learning of the postponement. The brigade had to lie on open ground under German artillery and machine-gun fire, which caused considerable loss but the left brigade was informed in time to hold back until 1:40 p.m. The bombardment began to creep down the slope at 3:10 p.m. at a rate of 100 yd (91 m) in three minutes. The right brigade advanced on a 2,000 yd (1,800 m) front towards the Oosttaverne line, from the river Douve north to the Blauwepoortbeek (Blue Gate Brook). German machine-gunners in the pillboxes of the Oosttaverne line caused many casualties but with support from three tanks the Australians reached the pillboxes, except for those to the north of the Messines–Warneton road. As the Australians outflanked the strongpoints, the Germans tried to retreat through the British barrage, which had stopped moving 300 yd (270 m) beyond the rear trench of the Oosttaverne line.[85]

The left flank brigade was stopped on its right flank by fire from the German pillboxes north of the Messines–Warneton road up to the Blauwepoortbeek, 500 yd (460 m) short of the Oosttaverne line, with many casualties. The left battalion, unaware that the 33rd Brigade (11th Division) to the north had been delayed, veered towards the north-east to try to make contact near Lumm Farm, which took the battalion across the Wambeke Spur instead of straight down. The objective was easily reached but at the Wambeek, 1,000 yd (910 m) north of the intended position. The Australians extended their line further north to Polka Estaminet trying to meet the 33rd Brigade, which arrived at 4:30 p.m. with four tanks. The brigade took Joye and Van Hove farms beyond the objective, silencing the machine-guns being fired from them.[86]

On the IX Corps front, the 33rd Brigade (11th Division) had been ordered to advance to Vandamme Farm at 9:25 a.m. but the message was delayed and the troops did not reach the assembly area at Rommens Farm until 3:50 p.m., half an hour late. To cover the delay, the corps commander ordered the 57th Brigade (19th Division) from reserve, to take the Oosttaverne line from Van Hove Farm to Oosttaverne village then to Bug Wood, so that only the southern 1,200 yd (1,100 m) were left for the 33rd Brigade. These orders were also delayed and the 19th Division commander asked for a postponement then ordered the 57th Brigade to advance without waiting for the 33rd Brigade. The troops only knew that they were to advance downhill and keep up to the barrage but were able to occupy the objective in 20 minutes against light opposition, meeting the Australians at Polka Estaminet.[86]

Two brigades of the 24th Division in Corps reserve advanced into the X Corps sector and reached Dammstrasse on time. The brigades easily reached their objectives around Bug Wood, Rose Wood and Verhaest Farm, taking unopposed many German pillboxes. The brigades captured 289 Germans and six field guns for a loss of six casualties, advancing 800 yd (730 m) along the Roozebeek valley, then took Ravine Wood unopposed on the left flank. The left battalion was drawn back to meet the 47th Division, which was still held up by machine-gun fire from the spoil bank. The final objectives of the British offensive had been taken, except for the area of the Ypres–Comines canal near the spoil bank and 1,000 yd (910 m) of the Oosttaverne line, at the junction of the II Anzac Corps and IX Corps. Despite a heavy bombardment until 6:55 p.m., the Germans at the spoil bank repulsed another infantry attack.[87] The reserve battalion which had been moved up for the second attack on the spoil bank, had been caught in a German artillery bombardment while assembling for the attack. The companies which attacked then met with massed machine-gun fire during the advance and only advanced half way to the spoil bank. The 207 survivors of the original 301 infantry, were withdrawn when German reinforcements were seen arriving from the canal cutting and no further attempts were made.[88]

The situation near the Blauwepoortbeek worsened, when German troops were seen assembling near Steingast Farm, close to the Warneton road. A British SOS barrage fell on the 12th Australian Brigade, which was inadvertently digging-in 250 yd (230 m) beyond its objective. The Australians stopped the German counter-attack with small-arms fire but many survivors began to withdraw spontaneously, until they stopped in relative safety on the ridge. As darkness fell and being under the impression that all the Australians had retired, New Zealand artillery observers called for the barrage to be brought closer to the observation line, when they feared a German counter-attack. The bombardment fell on the rest of the Australians, who withdrew with many casualties, leaving the southern part of the Oosttaverne line unoccupied, as well as the gap around the Blauwepoortbeek. An SOS barrage on the IX Corps front stopped a German counter-attack from the Roozebeke valley but many shells fell short, precipitating another informal withdrawal. Rumour led to the barrage being moved closer to the observation line, which added to British casualties until 10:00 p.m., when the infantry managed to get the artillery stopped and were then able to re-occupy the positions. Operations to re-take the Oosttaverne line in the II Anzac Corps area started at 3:00 a.m. on 8 June.[89]

Air operations

As the infantry moved to the attack contact-patrol aircraft flew low overhead, two being maintained over each corps during the day. The observers were easily able to plot the positions of experienced troops, who lit flares and waved anything to attract attention. Some troops, poorly trained and inexperienced, failed to co-operate, fearing exposure to the Germans; aircraft flew dangerously low to identify them, four being shot down in consequence.[90] Although air observation was not as vital to German operations because of their control of commanding ground, the speed by which reports from air observation could be delivered, made it a most valuable form of liaison between the front line and higher commanders. German infantry proved as reluctant to reveal themselves as the British and German flyers also had to make visual identifications.[91] Reports and maps were dropped at divisional headquarters and corps report centres, allowing the progress of the infantry to be followed.[92]

During the pause on the ridge crest, an observer reported that the Oosttaverne line was barely occupied; at 2:00 p.m. a balloon observer reported a German barrage on the II Anzac Corps front and a counter-attack patrol aircraft reported German infantry advancing either side of Messines. The German counter-attack was "crushed" by artillery fire by 2:30 p.m. Each corps squadron kept an aircraft on counter-attack patrol all day, to call for barrage fire if German troops were seen in the open but the speed of the British advance resulted in few German counter-attacks. Artillery observers watched for German gunfire and made 398 zone calls but only 165 managed to have German guns engaged.[93][lower-alpha 7] The observers regulated the bombardment of the Oosttaverne line and the artillery of VIII Corps to the north of the attack, which was able to enfilade German artillery opposite X Corps.[93]

Fourteen fighters were sent to conduct low altitude strafes on German ground targets ahead of the British infantry and rove behind German lines, attacking infantry, transport, gun-teams and machine-gun nests; the attacks continued all day, two of the fighters being shot down. Organised attacks were made on the German airfields at Bisseghem and Marcke near Courtrai and the day bombing squadrons attacked airfields at Ramegnies Chin, Coucou, Bisseghem (again) and Rumbeke. Reports of German troops concentrating from Quesnoy to Warneton were received and aircraft set out to attack them within minutes. German fighters made a considerable effort to intercept corps observation aircraft over the battlefield but were frustrated by patrols on the barrage line and offensive patrols beyond; only one British corps aircraft was shot down by German aircraft. After dark, the night-bombing specialists of 100 Squadron bombed railway stations at Warneton, Menin and Courtrai. The situation at the north end of the II Anzac Corps front was discovered by air reconnaissance at dawn on 8 June.[95]

German 4th Army

At 2:50 a.m. on 7 June, the British artillery bombardment ceased; expecting an immediate infantry assault, the German defenders returned to their forward positions. At 3:10 a.m. the mines were detonated, killing c. 10,000 German soldiers and destroying most of the middle breastwork Ib of the front system, paralysing the survivors of the eleven German battalions in the front line, who were swiftly overrun. The explosions occurred while some of the German front line troops were being relieved, catching both groups in the blasts and British artillery fire resumed at the same moment as the explosions.[96][lower-alpha 8] Some of the Stoßtruppen (Stormtroops) in breastwork Ic were able to counter-attack but were overwhelmed quickly as the British advanced on the Sonnestellung (Sun Position), which usually held half of the support battalions but had been reduced to about 100 men and six machine-guns, in each 800 yd (730 m) regimental zone.[98]

Smoke and dust from the British barrage limited visibility to 100 yd (91 m) and some defenders thought that figures moving towards them were retreating German soldiers, were taken by surprise and overrun. After a pause, the British continued to the Höhenstellung held by half of the support battalions, a company of each reserve battalion and 10–12 machine-guns per regimental sector. Despite daylight, German defenders only saw occasional shapes in the dust and smoke as they were deluged by artillery fire and machine-gunned by swarms of British aircraft.[98] The German defence in the south collapsed and uncovered the left flank of each unit further north in turn, forcing them to retire to the Sehnenstellung. Some German units held out in Wijtschate and near St Eloi, waiting to be relieved by counter-attacks which never came. The garrison of the Kofferberg (Caterpillar or spoil heap to the British) held on for 36 hours until relieved.[99]

Laffert had expected that the two Eingreif divisions behind Messines Ridge would reach the Höhenstellung before the British. The divisions had reached assembly areas near Gheluvelt and Warneton by 7:00 a.m. and the 7th Division was ordered to move from Zandvoorde to Hollebeke, to attack across the Comines canal towards Wijtschate on the British northern flank. The 1st Guard Reserve Division was to move to the Warneton line east of Messines, then advance around Messines to recapture the original front system. Both Eingreif divisions were plagued by delays, being new to the area and untrained for counter-attack operations. The 7th Division was shelled by British artillery all the way to the Comines canal, then part of the division was diverted to reinforce the remnants of the front divisions holding positions around Hollebeke.[100]

The rest of the division found that the British had already taken the Sehnenstellung, by the time that they arrived at 4:00 p.m. The 1st Guard Reserve Division was also bombarded as it crossed the Warneton (third) line but reached the area east of Messines by 3:00 p.m., only to be devastated by the resumption of the British creeping barrage and forced back to the Sehnenstellung as the British began to advance to their next objective. Laffert contemplated a further withdrawal, then ordered the existing line to be held after the British advance stopped.[100] Most of the losses inflicted on the British infantry by the German defence came from artillery fire. In the days after the main attack, German shellfire on the new British lines was extremely accurate and well-timed, inflicting 90 per cent of the casualties suffered by the 25th Division.[101]

Aftermath

Analysis

Historians and writers disagree on the strategic significance of the battle, although most describe it as a British tactical and operational success. In 1919, Ludendorff wrote that the British victory cost the German army dear and drained German reserves. Hindenburg wrote that the losses at Messines had been "very heavy" and that he regretted that the ground had not been evacuated; in 1922, Kuhl called it one of the worst German tragedies of the war.[102] In his Dispatches of 1920, Haig described the success of the British plan, organisation and results but refrained from hyperbole, referring to the operation as a successful preliminary to the main offensive at Ypres.[103] In 1930, Basil Liddell Hart thought the success at Messines inflated expectations for the Third Battle of Ypres and that because the circumstances of the operations were different, attempts to apply similar tactics resulted in failure.[104] In 1938 Lloyd George called the battle an aperitif and in 1939, G. C. Wynne judged it to be a "brilliant success", overshadowed by the subsequent tragedy of the Battles of Passchendaele.[105] James Edmonds, the official historian, called it a "great victory" in Military Operations France and Belgium 1917 Part II, published 1948.[106]

Prior and Wilson (1997) called the battle a "noteworthy success" but then complained about the decision to postpone exploitation of the success on the Gheluvelt plateau.[107] Ashley Ekins referred to the battle as a great set-piece victory, which was also costly, particularly for the infantry of II Anzac Corps, as did Christopher Pugsley, referring to the experience of the New Zealand Division.[108] Heinz Hagenlücke called it a great British success and that the loss of the ridge had a worse effect on German morale than the number of casualties.[109] Jack Sheldon called it a "significant victory" for the British and a "disaster" for the German army, which was forced into a "lengthy period of anxious waiting".[110] Ian Brown in his 1996 PhD thesis and Andy Simpson in 2001 concluded that extending British supply routes over the ridge, which had been devastated by the mines and millions of shells, to consolidate the Oosttaverne line was necessary. Completion of the infrastructure further north in the Fifth Army area, had to wait before the Northern Operation (Third Battle of Ypres) could begin and was the main reason for the operational pause in June and July.[111]

Casualties

In 1941, Charles Bean, the Australian official historian, recorded II Anzac Corps casualties from 1 to 14 June as 4,978 in the New Zealand Division, 3,379 in the 3rd Australian Division and 2,677 casualties in the 4th Australian Division.[112] In 1948, James Edmonds, the British official historian, gave casualties of 12,391 in the II Anzac Corps, 5,263 in IX Corps, 6,597 in X Corps, 108 in II Corps and 203 in VIII Corps, a total of 24,562 from 1 to 12 June.[113] The 25th Division history gave 3,052 casualties and the 47th Division history notes 2,303 casualties.[114]

Using figures from the Reichsarchiv, Bean recorded German casualties for 21 to 31 May as 1,963, from 1 to 10 June 19,923 (including 7,548 missing), from 11 to 20 June, 5,501 and 1,773 from 21 to 30 June. In volume XII of Der Weltkrieg the German Official Historians recorded 25,000 casualties for the period 21 May – 10 June including 10,000 missing of whom 7,200 were reported as taken prisoner by the British. The Reichsarchiv count of British casualties was 25,000 and a further 3,000 missing from 18 May to 14 June. The explosion of the mines, in particular the mine that created the Lone Tree Crater, accounts for the high number of casualties and missing from 1 to 10 June.[115] The German medical history, Sanitätsbericht über das Deutschen Heeres im Weltkrieg (Medical Services of the German Army in the World War) [1934], recorded 26,087 German casualties from 7 to 14 June.[116]

Edmonds recorded 21,886 German casualties, including 7,548 missing, from 21 May to 10 June, using strength returns from gruppen Ypern, Wijtschate and Lille in Der Weltkrieg, the German Official History, then wrote that 30 per cent should be added for wounded likely to return to duty within a reasonable time, since they were "omitted" in the German Official History, reasoning which has been disputed by other historians.[117] In 2007 Sheldon gave 22,988 casualties for the German 4th Army from 1 to 10 June 1917.[118]

Subsequent operations

At 3:00 a.m. on 8 June, the British attack to regain the Oosttaverne line from the river Douve to the Warneton road found few German garrisons present as it was occupied. German artillery south of the Lys bombarded the southern slopes of the ridge and caused considerable losses among Anzac troops pinned there. Ignorance of the situation north of the Warneton road continued; a reserve battalion was sent to reinforce the 49th Australian Battalion near the Blauwepoortbeek for the 3:00 a.m. attack, which did not take place. The 4th Australian Division commander, Major-General William Holmes, went forward at 4:00 a.m. and finally clarified the situation.[119]

New orders instructed the 33rd Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division, to side-step to the right and relieve the 52nd Australian Battalion, which at dusk would move to the south and join the 49th Australian Battalion to attack into the gap at the Blauwepoortbeek. All went well until observers on the ridge saw the 52nd Australian Battalion withdrawing, mistook it for a German counter-attack and called for an SOS bombardment. German observers in the valley saw troops from the 33rd Brigade moving into the area to relieve the Australians, mistook them for an attacking force and also called for an SOS bombardment. The area was deluged with artillery fire from both sides for two hours, causing many casualties and the attack was postponed until 9 June.[119][lower-alpha 9]

Confusion had been caused by the original attacking divisions on the ridge having control over the artillery covering the area occupied by the reserve divisions down the eastern slope. The arrangement had been intended to protect the ridge from large German counter-attacks, which might force the reserve divisions back up the slope. The mistaken bombardments of friendly troops ended late on 9 June, when the New Zealand, 16th (Irish) and 36th (Ulster) divisions were withdrawn into reserve and the normal corps organisation was restored; the anticipated large German counter-attacks had not occurred. On 10 June, the attack down the Blauwepoortbeek began but met strong resistance from the fresh German 11th Division, brought in from Group Ypres.[120]

The 3rd Australian Division advanced 600 yd (550 m) either side the river Douve, consolidating their hold on a rise around Thatched Cottage, which secured the right flank of the new Messines position; early on 11 June, the Germans evacuated the Blauwepoortbeek sector. British observation from the Oosttaverne line proved to be poor, which led Plumer to order an advance further down the slope. On 14 June, the II Anzac Corps was to push forward on the right from Plugstreet Wood to Trois Tilleuls Farm and Hill 20 and another 1,000 yd (910 m) to the Gapaard spur and Ferme de la Croix. IX Corps was to take Joye Farm, the Wambeke hamlet and come level with the Australians at Delporte Farm; X Corps was to capture the Spoil Bank and the areas adjacent. The attack was forestalled by a German retirement on the night of 10/11 June and by 14 June, British advanced posts had been established without resistance.[120]

Meticulously planned and well executed, the attack on the Messines–Wytschaete ridge secured its objectives in less than twelve hours. The combination of tactics devised on the Somme and at Arras, the use of mines, artillery survey, creeping barrages, tanks, aircraft and small-unit fire-and-movement tactics, created a measure of surprise and allowed the attacking infantry to advance by infiltration when confronted by intact defences. Well-organised mopping-up parties prevented by-passed German troops from firing on advanced troops from behind.[121] The British took 7,354 prisoners, 48 guns, 218 machine-guns and 60 trench mortars. The offensive secured the southern end of the Ypres salient in preparation for the British Northern Operation. Laffert, the commander of Gruppe Wijtschate, was sacked two days after the battle.[122]

Haig had discussed the possibility of rapid exploitation of a victory at Messines with Plumer before the attack, arranging for II and VIII Corps to advance either side of Bellewaarde Lake, using some of the artillery from the Messines front, which Plumer considered would take three days to transfer. On 8 June, patrols on the II and VIII Corps fronts reported strong resistance. Haig urged Plumer to attack immediately and Plumer replied that it would still take three days to arrange. Haig transferred the two corps to the Fifth Army and that evening, gave instructions to Gough to plan the preliminary operation to capture the area around Stirling Castle. On 14 June, Gough announced that the operation would put his troops into a salient and that he wanted to take the area as part of the main offensive.[123] On 13 June, German aircraft began daylight attacks on London and the south-east of England, leading to the diversion of British aircraft from the concentration of air forces for the Northern Operation.[124]

Victoria Cross

- Private John Carroll, 33rd Battalion, 3rd Australian Division.[125]

- Lance-Corporal Samuel Frickleton, 3rd Battalion, New Zealand Rifles, New Zealand Division.[126]

- Captain Robert Cuthbert Grieve, 37th Battalion, 3rd Australian Division.[127]

- Private William Ratcliffe, 2nd South Lancashire Regiment, 25th Division.[128]

See also

- List of the largest artificial non-nuclear explosions

- Mines in the Battle of Messines (1917)

- Ronald Skirth, British pacifist artilleryman, vowed not to take another human life after the Battle of Messines

Notes

- Spellings and place names follow the usage in the British Official History (1948) except in the sections where the source is in German, when equivalent contemporary forms are used. Modern Belgian usage has been avoided, because the Belgian state has French, Dutch (including Flemish) and German as official languages and a local system of precedence, not relevant to events in 1917.[1]

- From 30 January 1916, each British army had a Royal Flying Corps brigade attached, which was divided into a corps wing with squadrons responsible for close reconnaissance, photography and artillery observation on the front of each army corps and an army wing, which by 1917, conducted long-range reconnaissance and bombing, using aircraft types with the highest performance.[28]

- X Corps (Lieutenant-General Sir Thomas Morland) with the 23rd, 47th, 41st Divisions and 24th Division in reserve. IX Corps ( Lieutenant-General Sir Alexander Hamilton-Gordon) with the 19th (Western), 16th Irish, 36th Ulster Divisions and 11th (Northern) Division in reserve. To the south-east, the II Anzac Corps (Lieutenant-General Sir Alexander Godley) with the 25th, New Zealand Division (including the New Zealand (Māori) Pioneer Battalion) and 3rd Australian Division with the 4th Australian Division in reserve.[44] II Brigade, Heavy Branch Machine-Gun Corps, with 72 of the new Mk IV tanks was in support, (20 tanks with II Anzac Corps, 16 with IX Corps, 12 with X Corps plus 24 in reserve).[45] The tanks were mainly to attack on the flanks at Dammstrasse in the north and Messines in the south. XIV Corps was held in reserve with Guards Division, 1st Division, 8th Division and 32nd Division.[43]

- German terms and spellings from the time have been used in the sections referring to German army dispositions and operations, to avoid Anglo-centric bias.

- The series of mines exploded over a period of 19 seconds, mimicking the effect of an earthquake; 15 mi (24 km) away in Lille, German troops ran around "panic-stricken".[66] That the detonations were not simultaneous added to the effect on German troops, as the explosions moved along the front. Odd acoustic effects also added to the shock; Germans on Hill 60 thought that the Kruisstraat and Spanbroekmolen mines were under Messines village, well behind their front line and some British troops thought that they were German counter-mines, going off under British support trenches.[66]

- Many considered this joint effort to be of considerable political significance, given the turmoil in Ireland at the time.[74] The Irish Nationalist Party MP Major William Redmond was fatally wounded.[75]

- Zones were based on lettered squares of the army 1:40,000 map; each map square was divided into four sections 3,000 yd (1.7 mi; 2.7 km) square. The observer used a call sign of the map square letter then the zone letter to signal to the artillery. All guns and howitzers up to 6 in (150 mm) able to bear on the target, opened rapid fire using corrections of aim from the air observer.[94]

- Reports were made that the shock wave from the explosion was heard as far away as London and Dublin. The 1917 Messines mines detonation was probably the largest planned explosion in history prior to the Trinity atomic weapon test in July 1945 and the largest non-nuclear planned explosion before the British explosive efforts on the Heligoland Islands in April 1947. The Messines detonation is history's deadliest non-nuclear man-made explosion. Several of the mines at Messines did not go off on time. On 17 July 1955, lightning set one off, killing a cow. Another mine, which had been abandoned as a result of its discovery by German counter-miners, is believed to have been found but no attempt has been made to remove it.[97]

- The 49th Australian Battalion had 379 casualties and the 52nd Australian Battalion 325 casualties in the Battle of Messines, most occurring from 7 to 8 June.[112]

References

Citations

- Portal Belgium 2012.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 85.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 3–4.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 236.

- Edmonds 1992, p. 312.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 416–417.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 124.

- Edmonds & Wynne 1995, p. 353.

- Hart & Steel 2001, pp. 18–19.

- Terraine 1977, p. 2.

- Hart & Steel 2001, p. 42.

- Liddle 1997, p. 141.

- Liddle 1997, p. 142.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 125.

- Liddle 1997, pp. 120–121.

- Liddle 1997, pp. 121–123.

- Cleland 1918, pp. 145–146; Branagan 2005, pp. 294–301.

- Wolff 2001, p. 88; Liddell Hart 1936, p. 331.

- Wolff 2001, p. 92.

- Bülow & Kranz 1943, pp. 103–104.

- Wolff 2001, p. 88.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 52–53.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 53.

- Terraine 1977, p. 118.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 49.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 33.

- Jones 2002a, p. 118.

- Jones 2002, pp. 147–148.

- Jones 2002a, pp. 110–118, 125.

- Kincaid-Smith 2010, pp. 51–52.

- Kincaid-Smith 2010, pp. 50–53.

- Kincaid-Smith 2010, pp. 64–65.

- Kincaid-Smith 2010, pp. 60–62.

- Maude 1922, pp. 101–102.

- Maude 1922, pp. 96–98.

- Wise 1981, p. 410.

- Jones 2002a, p. 116.

- Wise 1981, p. 409.

- Jones 2002a, pp. 112–117, 124.

- Wise 1981, p. 411.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 418.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 32.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 417–419.

- Wolff 2001, p. 98.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 33, 67.

- Farndale 1986, p. 186.

- Farndale 1986, p. 191.

- Farndale 1986, p. 185.

- Simpson 2001, p. 110.

- Hart & Steel 2001, pp. 45, 54.

- Liddell Hart 1936, p. 332.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 416–418.

- Wynne 1976, p. 262.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 262–263.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 265–266.

- USWD 1920.

- Sheldon 2007, pp. 1–3.

- Wynne 1976, p. 266; Edmonds 1991, p. 65.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 266–271.

- Wynne 1976, p. 268.

- Wynne 1976, p. 271.

- Jones 2002a, pp. 119–120.

- Wynne 1976, p. 269.

- Jones 2002a, p. 413.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 54.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 55.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 54–55.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 56–57.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 57–59.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 59–61.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 61–63.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 63–64.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 64–65.

- Liddell Hart 1936, p. 334.

- Burnell 2011, p. 213.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 65–66.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 66.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 67–68.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 68–69.

- Maude 1922, p. 100.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 69–70.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 70.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 71.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 75–77.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 77–80.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 80.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 80–82.

- Maude 1922, pp. 100–101.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 82–84.

- Jones 2002a, p. 126.

- Hoeppner 1994, pp. 110–111.

- Jones 2002a, p. 127.

- Jones 2002a, pp. 127–129.

- Jones 2002, pp. 175–176.

- Jones 2002a, pp. 129–133.

- Groom 2002, p. 167; Edmonds 1991, pp. 54–55.

- Duffy 2000.

- Wynne 1976, p. 275.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 272–275.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 278–281.

- Kincaid-Smith 2010, p. 69.

- Terraine 1977, p. 121; Edmonds 1991, p. 94.

- Boraston 1920, pp. 108–109.

- Liddell Hart 1936, pp. 339–340.

- Wynne 1976, pp. 280–281.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 87.

- Prior & Wilson 1996, pp. 64–65.

- Liddle 1997, pp. 231, 276.

- Liddle 1997, p. 50.

- Sheldon 2007, pp. 28–29.

- Simpson 2001, pp. 113–144; Brown 1996, pp. 228–229.

- Bean 1982, p. 682.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 87–88.

- Kincaid-Smith 2010, p. 69; Maude 1922, p. 103.

- Foerster 1939, p. 471.

- Sanitätsbericht 1934, p. 53.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 88; McRandle & Quirk 2006, pp. 667–701; Liddle 1997, p. 481.

- Sheldon 2007, p. 315.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 84.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 85–87.

- Groom 2002, p. 169.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 94.

- Edmonds 1991, pp. 88–90.

- Liddle 1997, p. 164.

- Bean 1982, p. 595.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 63.

- Edmonds 1991, p. 79.

- Kincaid-Smith 2010, p. 71.

Bibliography

Books

- Bean, C. E. W. (1982) [1941]. The Australian Imperial Force in France, 1917. Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918. Vol. IV (11th ed.). St Lucia, Queensland: University of Queensland in Association with the Australian War Memorial. ISBN 978-0-7022-1710-4 – via Australian War Memorial.

- Boraston, J. H. (1920). Sir Douglas Haig's Despatches (December 1915 – April 1919). London: Dent. OCLC 479257.

- Branagan, D. F. (2005). T. W. Edgeworth David: A Life: Geologist, Adventurer, Soldier and "Knight in the old brown hat". Canberra: National Library of Australia. ISBN 978-0-642-10791-6.

- Bülow, K. von; Kranz, W.; Sonne, E.; Burre, O.; Dienemann, W. (1943) [1938]. Wehrgeologie [Military Geology] (Engineer Research Office, New York ed.). Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer. OCLC 44818243.