Warhammer 40,000

Warhammer 40,000[lower-alpha 1] is a miniature wargame produced by Games Workshop. It is the most popular miniature wargame in the world,[1][2] and is particularly popular in the United Kingdom.[3] The first edition of the rulebook was published in September 1987, and the ninth and current edition was released in July 2020.

| |

| Manufacturers | Games Workshop, Citadel Miniatures, Forge World |

|---|---|

| Years active | 1987–present |

| Players | 2+ |

| Setup time | 5–20+ minutes |

| Playing time | 30–180+ minutes |

| Chance | Medium (dice rolling) |

| Skills | Strategic thinking, arithmetic, miniature painting |

| Website | warhammer40000 |

As in other miniature wargames, players enact battles using miniature models of warriors and fighting vehicles. The playing area is a tabletop model of a battlefield, comprising models of buildings, hills, trees, and other terrain features. Each player takes turns moving their model warriors around the battlefield and fighting their opponent's warriors. These fights are resolved using dice and simple arithmetic.

Warhammer 40,000 is set in the distant future, where a stagnant human civilization is beset by hostile aliens and supernatural creatures. The models in the game are a mixture of humans, aliens, and supernatural monsters, wielding futuristic weaponry and supernatural powers. The fictional setting of the game has been developed through a large body of novels, published by Black Library (Games Workshop's publishing division). Warhammer 40,000 took its name from Warhammer Fantasy Battle, which is a medieval fantasy wargame also produced by Games Workshop. Warhammer 40,000 was initially conceived as a science fiction counterpart to Warhammer Fantasy, and while they are not connected to each other in a shared universe, their settings share similar themes.

Warhammer 40,000 has spawned a number of spin-off tabletop games. These include Space Hulk, which is about combat within the narrow corridors of derelict spacecraft, and Battlefleet Gothic which simulates spaceship combat. Video game spin-offs, such as the Dawn of War series, have also been released.

Overview

Note: The overview here references the 9th edition of the rules, published in July 2020

The rulebooks and miniature models required to play Warhammer 40,000 are copyrighted and sold exclusively by Games Workshop and its subsidiaries. These and other materials (dice, measuring tools, glue, paints, etc.) all make Warhammer 40,000 expensive as far as gaming hobbies go. A new player can expect to spend at least $400 to assemble enough materials for a "proper" game,[4][5] and the armies that appear in tournaments can surpass $600.[6]

Miniature models

Games Workshop sells a large variety of gaming models for Warhammer 40,000, but no ready-to-play models. Rather, it sells boxes of model parts, which players are expected to assemble and paint themselves. Most Warhammer 40,000 models are made of polystyrene, but certain models which are made and sold in small volumes are made of lead-free pewter or epoxy resin. Games Workshop also sells glue, tools, and acrylic paints for this. The assembly and painting of the models is a major aspect of the hobby, and many customers of Games Workshop buy models simply to paint and display them. A player might spend weeks assembling and painting models before they have a playable army.

Each miniature model represents an individual warrior or vehicle. In the rulebooks, there is an entry for every type of model in the game that describes its combat capabilities. For instance, a model of a Tactical Space Marine has a "Move" range of 6 inches and a "Toughness" rating of 4, and is armed with a "bolt gun" with a range of 24 inches.

Officially, Warhammer 40,000 does not have a scale, but the models approximate a scale ratio of 1:60.[7] For instance, a Land Raider tank model is 17 cm long but conceptually 10.3 m long. This scale does not correspond to the range of firearms: on the table, a boltgun has a range of 24 inches, which corresponds to only 120 feet (36.6 m) at a 1:60 scale. A model of a Primaris Space Marine is about 4.5 cm in height.

Playing field

The current official rulebook recommends a table width of 44 inches (1.1 m), and table length varies based on the size of the armies being used (discussed below).[8] In contrast to board games, Warhammer 40,000 does not have a fixed playing field. Players are expected to construct their own custom-made battlefield using modular terrain models. Games Workshop sells a variety of proprietary terrain models, but players often use generic or homemade ones too. Unlike certain other miniature wargames, such as BattleTech, Warhammer 40,000 does not use a grid system. Players must use a measuring tape (and templates in earlier editions) to measure distances. Distances are measured in inches.

Assembling armies

An "army" in this context refers to all the model warriors that a player has selected to use in a match. In Warhammer 40,000, players are not restricted to playing with a fixed and symmetrical combination of warriors as in chess. They get to choose which warriors and armaments they will fight with from a catalog presented in the rulebooks. The players must pick and agree on what models they will play with before the match starts, and once the match is underway, they cannot add any new models to their armies. The players may choose the models they will play with, subject to some limitations.

Due to matters of practical necessity, the miniature models used by players should typically follow the specifications of those designed and sold by Games Workshop specifically for use in Warhammer 40,000, corresponding to the warriors the player wants in his army. Substituting miniature models made for other games may cause confusion, as the players may have difficulty keeping track of which kind of warrior a third-party model is intended to represent. For instance, a player cannot use a model of a Greek hoplite in a Warhammer 40,000 match because the rulebooks provide no rules or stats for Greek hoplites, and Greek hoplites do not exist in the setting of Warhammer 40,000. Furthermore, substitute models may not match the size of the proper model, particularly with regard to the base on which the figurine is mounted, and this is important because the space the model occupies on the playing field affects the play. Warhammer 40,000, after all, is not played on a grid. Additionally, in official tournaments, it is mandatory for players to only use Games Workshop's models, and those models must be properly assembled and painted to match the player's army roster; substitutes are forbidden. For example, if a player wants to use an Ork Weirdboy in his match, they must use an Ork Weirdboy model from Games Workshop.[9] Games Workshop has also banned the use of 3D-printed miniatures in official tournaments.[10] Public tournaments organized by independent groups might permit third-party models so long as the models are clearly identifiable as the warriors they're meant to represent.

The composition of the players' armies must fit the rivalries and alliances depicted in the setting. All model warriors listed in the rulebooks are classified into "factions", such as "Imperium", "Chaos", "Tau Empire", etc. In a matched game, a player may only use warrior models in their army that are all loyal to a common faction.[11] Thus, a player cannot, for example, use a mixture of Aeldari and Necron model warriors in their army. That would not make sense, for, in the game's fictional setting, Aeldari and Necrons are mortal enemies and would never fight alongside each other.

The game uses a point system to ensure that the match will be "balanced", i.e. the armies will be of equal overall strength. The players must agree as to what "points limit" they will play at, which roughly determines how big and powerful their respective armies will be. Each model and weapon has a "point value" which roughly corresponds to how powerful the model is; for example, a Tactical Space Marine is valued at 13 points, whereas a Land Raider tank is valued at 239 points.[12] The sum of the point values of a player's models must not exceed the agreed limit. If the point values of the players' respective armies both add up to the limit, they are assumed to be balanced. 1,000 to 3,000 points are common point limits. In the most recent edition of the game, power levels are assigned to each model, which can be used to simplify or vary the process of creating an army list.[13] Power levels work in the same way as points but are less granular. This makes them a simpler but less effective way of balancing lists.

Although the rules place no limit on how big an army can be, players tend to use small armies of about two dozen models. A large army will slow down the pace of the match as the players have many more models to handle and think about. Large armies also cost a lot of money and take a lot of work to paint and assemble.

Moving and attacking

.jpg.webp)

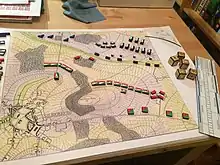

At the start of a game, each player places their models in starting zones at opposite ends of the playing field.

At the start of their turn, a player moves each model in their army by hand across the field. A model can be moved no farther than its listed "Move characteristic". For instance, a model of a Space Marine can be moved no farther than six inches per turn. If a model cannot fly, it must go around obstacles such as walls and trees.

Models are grouped into "units". They move, attack, and suffer damage as a unit. All models in a unit must stay close to each other. Each model in a unit must finish a turn within two inches of another model from the unit. If there are more than five models in a unit, each model must be within two inches of two other models.

After moving, each unit can attack any enemy unit within range and line-of-fire of whatever weapons and psychic powers its models have. For instance, a unit of Space Marines armed with "boltguns" can shoot any enemy unit within 24 inches. The attacking player rolls dice to determine how much damage their models inflicted on the enemy unit. The attacking player cannot target individual models within an enemy unit; if an enemy unit suffers damage, the enemy player decides which models in the unit suffered injury.[14] Damage is measured in points, and if a model suffers more points of damage than its "Wound characteristic" permits, it dies. Dead models are removed from the playing field. Most models have only one Wound point, but certain models such as "hero characters" and vehicles have multiple Wound points, so the damage they accumulate must be recorded on paper.

Most of the races in the game have units with psychic powers. Psyker units can cause unusual effects, such as rendering allied units invulnerable or teleporting units across the battlefield. Any psyker unit can nullify the powers of an enemy psyker by making a Deny the Witch roll.[15]

Victory conditions

Victory depends on what kind of "mission" the players select for their game. It might involve exterminating the enemy, or holding a location on the field for a certain length of time, or retaining possession of a holy relic for a certain length of time.

Setting

Most Warhammer 40,000 fiction is set around the turn of the 42nd millennium (about 39,000 years in the future). Although Warhammer 40,000 is mostly a science-fiction setting, it adapts a number of tropes from fantasy fiction, such as magic, supernatural beings, daemonic possession, and fantasy races such as orcs and elves; "psykers" fill the role of wizards in the setting. The setting of this game inherits many fantasy tropes from Warhammer Fantasy (a similar wargame from Games Workshop), and by extension from Dungeons and Dragons. Games Workshop used to make miniature models for use in Dungeons and Dragons, and Warhammer Fantasy was originally meant to encourage customers to buy more of their miniature models. Warhammer 40,000 itself was originally conceived as a science-fiction spin-off of Warhammer Fantasy.

Although they have similar names and share some characters and tropes, the settings of Warhammer 40,000 and Warhammer Fantasy are completely separate. For instance, the Chaos God Slaanesh in Warhammer Fantasy is not the same Slaanesh that appears in Warhammer 40,000. The Emperor of Mankind does not exist in Warhammer Fantasy and Sigmar does not exist in Warhammer 40,000.

The setting of Warhammer 40,000 is violent and pessimistic. It depicts a future where human scientific and social progress have ceased, and human civilisation is in a state of total war with hostile alien races and occult forces. It is a setting where the supernatural exists, is powerful, and is usually untrustworthy if not outright malevolent. There are effectively no benevolent gods or spirits in the cosmos, only daemons and evil gods, and the cults dedicated to them are proliferating. In the long run, the Imperium of Man cannot hope to defeat its enemies, so the heroes of the Imperium are not fighting for a brighter future but "raging against the dying of the light".[16] The tone of the setting has led to a subgenre of science fiction called "grimdark", which is particularly amoral, dystopian or violent.[17]

As the setting is based on a wargame, the spin-off novels and comic books are mostly war dramas with protagonists who are usually warriors of some sort, the most popular being the Space Marines. The Imperium is in a state of total war. Many planets in the Imperium of Man are either warzones or heavily burdened by wartime taxation, and civil liberties are heavily curtailed in the name of security.

The source of magic in the setting is a parallel universe of supernatural energy known as "the Warp". All living creatures with souls are tied to the Warp, but certain individuals called "psykers" have an especially strong link and can manipulate the Warp's energy to work magic. Psykers are generally feared and mistrusted by humans. Psykers may possess many dangerous abilities such as mind control, clairvoyance, and pyrokinesis. Moreover, the Warp is full of predatory creatures that may use a psyker's link to the Warp as a conduit by which to invade realspace. But for all the dangers that psykers pose, human civilisation cannot do without them: their telepathic powers provide faster-than-light communication and on the battlefield they are the best counter to enemy psykers. For this reason, the Imperium rounds up any psykers it finds and trains them to control their abilities and resist Warp predators. Those who fail or reject this training are executed for the safety of all. Those who pass their training are pressed into life-long servitude to the state and are closely monitored for misconduct and spiritual corruption.[18]

Influences

Rick Priestley cites J. R. R. Tolkien, H. P. Lovecraft, Dune, Paradise Lost, and 2000 AD as major influences on the setting.

The Chaos Gods were added to the setting by Bryan Ansell and developed further by Priestley. Priestley felt that Warhammer's concept of Chaos, as detailed by Ansell in the supplement Realms of Chaos, was too simplistic and too similar to the works of Michael Moorcock, so he developed it further, taking inspiration from Paradise Lost.[19] The story of the Emperor's favored sons succumbing to the temptations of Chaos deliberately parallels the fall of Satan in Paradise Lost. The religious themes are primarily inspired by the early history of Christianity. Daemons in WH40K are the embodiment of human nightmares and dark emotion, given physical form and sentience by the Warp—this idea comes from the 1956 movie Forbidden Planet.[20]

The Emperor of Man was inspired by various fictional god-kings, such as Leto Atreides II from the novel God Emperor of Dune by Frank Herbert, and King Huon from the Runestaff novels by Michael Moorcock. The Emperor's suffering on the Golden Throne for the sake of humanity mirrors the sacrifice of Jesus Christ.

Humans fear artificial intelligence and creating or protecting an artificial intelligence is a capital offence. This comes from the Dune novels. As in the Dune setting, the prohibition on artificial intelligence was passed after an ancient war against malevolent androids.

The Eldar Webway was inspired by the Underdark from various Dungeons and Dragons settings. The dark elves live underground and travel the world through a network of tunnels, with openings to the surface here and there which they use to raid human communities, and they build their cities in the largest caverns. Likewise, in Warhammer 40,000, the Eldar travel the galaxy through a maze of magical tunnels, and the Dark Eldar's home city of Commoragh lies in the largest Webway cavern.

To me the background to 40K was always intended to be ironic. [...] The fact that the Space Marines were lauded as heroes within Games Workshop always amused me, because they're brutal, but they're also completely self-deceiving. The whole idea of the Emperor is that you don't know whether he's alive or dead. The whole Imperium might be running on superstition. There's no guarantee that the Emperor is anything other than a corpse with a residual mental ability to direct spacecraft. It's got some parallels with religious beliefs and principles, and I think a lot of that got missed and overwritten.

— Rick Priestley, in a December 2015 interview with Unplugged Games[21]

Factions

The models available for play in Warhammer 40,000 are divided into "factions". Under normal circumstances, a player can only use units from the same faction in their army. For instance, a player's army cannot include both Ork and Aeldari models because Orks and Aeldari are enemies in the setting.

The Imperium of Man

The Imperium of Man is a human empire that comprises approximately 1 million worlds and has existed for over 10,000 years. Its government is a mixture of fascism, theocracy, and feudalism. The most important aspect of the Imperium is its state religion centred around the Emperor of Mankind, an extremely powerful psyker whom they worship as a god. Anyone who does not revere the Emperor properly is liable to be persecuted for heresy. The Emperor founded the Imperium and is still its nominal ruler, but roughly two centuries after founding the Imperium he was mortally wounded in battle and has been on life support in an unresponsive state ever since. Despite his condition, his mind still generates a psychic beacon by which starships navigate the Warp, making him the linchpin of the Imperium's infrastructure. Although the Imperium has highly advanced technology, it has only recently continued the practice of science and many of its technologies have not improved for thousands of years. Imperial citizens are taught to obey authority without question, to worship the Emperor, to hate aliens, and to be incurious about anything that does not concern their duties. Most Warhammer 40,000 fiction has humans of the Imperium as the protagonists, with other races being antagonists or supporting characters.

Of all the factions, the Imperium has the largest catalogue of models, which gives Imperium players the flexibility to design their army for any style of play. That said, players tend to build their armies around specific sub-factions which have more focused playstyles. For instance, an army of Space Marines will consist of a small number of powerful infantry, whereas an Imperial Guard army will have weak but plentiful infantry combined with strong artillery.

Chaos

Chaos represents the myriad servants of the Chaos Gods, malevolent and depraved entities formed from the base thoughts and emotions of mortals. Those exposed to the influence of the Chaos are twisted in both mind and body and perform sordid acts of devotion to their dark gods, who in turn reward them with "gifts" such as physical mutations, psychic power, and mystical artifacts. Like their gods, the servants of Chaos are malevolent and insane, adopting the aesthetics of body horror and cosmic horror in the design of their models and story details. The ongoing conflict between those still loyal to the Emperor of Mankind and those who have "fallen" to the Chaos Gods is central to the setting of Warhammer 40,000.

As with the Imperium, Chaos players have access to a large variety of models, allowing them to design their army for any style of play. That said, players tend to theme their army around a particular Chaos God, which focuses the style of play. For instance, an army themed around Nurgle will consist of slow-moving but tough warriors. Likewise, a Chaos army themed around Khorne will lean towards melee combat and eschew psykers.

Necrons

The Necrons are an ancient race of skeleton-like androids. Millions of years ago, they were flesh-and-blood beings, but then they transferred their minds into android bodies, thereby achieving immortality.[22] However, the transference process was flawed, as they all lost their souls and all but the highest ranking ones became mindless as well. They are waking up from millions of years of hibernation in underground vaults on planets across the galaxy, and seek to rebuild their old empire. The Necrons have an ancient Egyptian aesthetic to them, although they are not based on the Tomb Kings of Warhammer Fantasy.

Necron infantry have strong ranged firepower, tough armour, and slow movement. Necron units have the ability to rapidly regenerate wounds or "reanimate" slain models at the start of the player's turn. All Necron models have a Leadership score of 10, so Necrons rarely suffer from morale failure. Necrons do not have any psykers, which makes them somewhat more vulnerable to psychic attacks as they cannot make Deny the Witch rolls. The Necrons possess "C'tan shards" which function much like psykers, but since these are not actual psykers, they cannot make Deny the Witch rolls, nor can their powers be countered by enemy Deny the Witch rolls.

Aeldari

The Aeldari (formerly referred to as the Eldar) are based on High Elves of fantasy fiction. Aeldari have very long lifespans and all of them have some psychic ability. The Aeldari travel the galaxy via a network of magical tunnels called "the Webway", over which they have exclusive access. In the distant past, the Aeldari ruled an empire that dominated much of the galaxy, but it was destroyed in a magical cataclysm along with most of the population. The surviving Aeldari are divided into two major subfactions: the ascetic inhabitants of massive starships called Craftworlds; and the sadistic Drukhari (also known as "Dark Eldar"), who inhabit a city hidden within the Webway. There are a number of minor subfactions too: the Harlequins, followers of the Laughing God Cegorach; and the Ynnari, followers of the death god Ynnead. Although it has been 10,000 years since their empire's fall, the Aeldari have never recovered, due to their low fertility and aggression by other races.

Craftworld Aeldari infantry tend to be highly specialised and relatively frail, often described as "glass cannons." Because of their lack of staying power and flexibility, Aeldari armies can suffer severe losses after a bad tactical decision or even unlucky dice rolls, while successful gameplay can involve outnumbered Aeldari units which outmanoeuvre the opponent and kill entire squads before they have a chance to retaliate. Aeldari vehicles, unlike their infantry counterparts, are very tough and hard to kill because of many evasive and shielding benefits. With the exception of walkers, all Aeldari vehicles are skimmers which allow them to move "freely" across difficult terrain, and with upgrades, at speeds only matched by the Dark Aeldari and the Tau armies.

Dark Aeldari are similar to Craftworld Aeldari in that they are typically frail but move quickly and deal a high amount of damage relative to their points costs. Unlike Craftworld Aeldari, the Dark Aeldari have no psykers.

Orks

The Orks are green-skinned aliens based on the traditional orcs of high fantasy fiction. Orks are a comical species, possessing crude personalities, wielding ramshackle weaponry, and speaking with Cockney accents. Their culture revolves around war for the sake of it. Unlike other races which generally only go to war when it is in their interests, the Orks recklessly start unnecessary conflicts for the pleasure of a good fight. Orks do not fear death and combat is the only thing that gives them emotional fulfillment. Ork technology consists of dashed together scrap that by all logic should be unreliable if even functional, but Orks generate a magical field that makes their ramshackle technology work properly. If a non-Ork tried to use an Ork gadget, it would likely malfunction.

Ork infantry models are slow-moving and tough. The Orks are oriented towards melee combat. An Ork player can re-roll failed charge rolls.[23] Infantry models are cheap (by point cost), so a favourite strategy is "the Green Tide": the player fields as many Orks as they can and simply marches them across the playing field to swarm his opponent. Orks do have a number of specialist models who can do things like psychic powers and repairing vehicles, but typically Ork warfare is about brute force and attrition. Ork gameplay is seen as fairly forgiving of tactical errors and bad die rolls.

Tyranids

The Tyranids are a mysterious alien race from another galaxy. They migrate from planet to planet, devouring all life in their path. Tyranids are linked by a psychic hive mind and individual Tyranids become feral when separated from it. Tyranid "technology" is entirely biological, ships and weapons being purpose-bred living creatures.

Tyranids have a preference for melee combat. Their infantry models tend to be fast and hard-hitting but frail. They have low point costs, meaning Tyranid armies in the game are relatively large (many cheap weak models, as opposed to armies with few expensive powerful models such as the Space Marines). Tyranids also have the most powerful counter-measures against enemies with psychic powers: many Tyranid models possess a trait called "Shadow in the Warp", which makes it harder for nearby enemy psykers to use their psychic powers.[24]

There is a sub-species of the Tyranid race called "Genestealers". Genestealers are inspired by H. P. Lovecraft's novella The Shadow over Innsmouth.[25] When a human is infected by a Genestealer, they are psychically enslaved and will sire children who are human-genestealer hybrids. These hybrids will form a secret society known as a Genestealer Cult within their host human society, steadily expanding their numbers and political influence. When a Tyranid fleet approaches their planet, they will launch an uprising to weaken the planet's defences so that the Tyranids may more easily conquer it and consume its biomass.

In earlier editions of the game, Genestealer Cults could only be used as auxiliaries to a regular Tyranid army, but since 8th edition, they can be played as a separate army. Although there is a dedicated line of Genestealer Cult models, a player can also use models from the Imperial Guard (a sub-faction of the Imperium) in their Genestealer Cult army. This is an exception to the common-faction rule and is based on the logic that these "human" models are actually Genestealer hybrids who look perfectly human. Like other Tyranids, Genestealers are hard-hitting but fragile. All Genestealer Cult infantry and bikers have a trait called "Cult Ambush" that allows them to be set up off table and later be set up on the table, instead of being set up in the designated starting zones at the start of the game (similar to the Space Marines' "Deep Strike" ability).

T'au

The T'au are a race of blue-skinned aliens inhabiting a relatively small but growing empire located on the fringes of the Imperium of Man. The T'au Empire is the only playable faction in the setting that integrates different alien species into their society. They seek to unite all other races under an ideology they call "the Greater Good" or "T'au'va". Some human worlds have willingly defected from the Imperium to join the T'au Empire. The humans tend to have a better quality of life than Imperial citizens because the T'au practice humane ethics and encourage scientific progress. The T'au are divided into five endogamous castes: the Ethereals, who are the spiritual leaders; the Fire Caste, who are professional soldiers; the Air Caste, who operate starships; the Water Caste, who are merchants and diplomats; and the Earth Caste, who are scientists, engineers, and labourers.

The T'au are oriented towards ranged combat and generally shun melee. They have some of the most powerful firearms in the game in terms of both range and stopping power. For instance, their pulse rifle surpasses the firepower of the Space Marine boltgun,[26] and the railgun on their main battle tank (the Hammerhead) is more powerful than its Imperium counterparts. The T'au do not have any psykers nor units that specialise in countering psykers, which makes them somewhat more vulnerable to psychic attacks. Most T'au vehicles are classified as flyers or skimmers, meaning they can move swiftly over difficult terrain. The T'au also incorporate alien auxiliaries into their army: the Kroot provide melee support and the insectoid Vespids serve as jump infantry.

History

In 1982, Rick Priestley joined Citadel Miniatures, a subsidiary of Games Workshop that produced miniature figurines for use in Dungeons and Dragons. Bryan Ansell (the manager of Citadel) asked Priestley to develop a medieval-fantasy miniature wargame that would be given away for free to customers so as to encourage them to buy more miniatures. Dungeons and Dragons did not require players to use miniature figurines, and even when players used them they rarely needed more than a handful.[27] The result was Warhammer Fantasy Battle, which was released in 1983 to great success.

Warhammer Fantasy was principally a medieval fantasy game in the vein of Dungeons and Dragons, but Priestley and his fellow designers added a smattering of optional science fiction elements, namely in the form of advanced technological artefacts (e.g. laser weapons) left behind by a long-gone race of spacefarers. Warhammer 40,000 was an evolution of this taken to the opposite extreme (i.e. mostly science-fiction but with some fantasy elements).

Since before working for Games Workshop, Priestley had been developing a spaceship combat tabletop wargame called "Rogue Trader", which mixed science fiction with classic fantasy elements. Priestley integrated many elements of the lore of "Rogue Trader" into Warhammer 40,000, chiefly those concerning space travel, but he discarded the ship combat rules for lack of space in the book.

Games Workshop planned to sell conversion kits by which players could modify their Warhammer Fantasy models to wield futuristic weaponry such as laser weapons, but eventually Games Workshop decided to create a dedicated line of models for Warhammer 40,000.

Initially, Priestley's new game was simply to be titled Rogue Trader, but shortly before release Games Workshop signed a contract with 2000 AD to develop a board game based on their comic book Rogue Trooper. So as not to confuse customers, Games Workshop renamed Priestley's game Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader and marketed it as a spin-off of Warhammer Fantasy Battle (which in many ways, it was).

Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader received its first full preview in White Dwarf #93 (September 1987).

Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader was released in October 1987. It was a success and became Games Workshop's most important product. In the January 1988 edition of Dragon (issue 129), Ken Rolston raved about this game, calling it "colossal, stupendous, and spectacular... This is the first science-fiction/fantasy to make my blood boil."[28]

First edition (Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader) (1987)

The first edition of the game was titled Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader, and its rules are based on Warhammer Fantasy Battle.[29] "Rogue Trader" had been the game's working title during development. The "Rogue Trader" subtitle was dropped in subsequent editions. It was published in 1987.[30] Game designer Rick Priestley created the original rules set (based on the contemporary second edition of Warhammer Fantasy Battle) alongside the Warhammer 40,000 gameworld. The gameplay of Rogue Trader was heavily oriented toward role-playing rather than strict wargaming. This original version came as a very detailed, though rather jumbled, rulebook, which made it most suitable for fighting small skirmishes.[31] Much of the composition of the units was determined randomly, by rolling dice. A few elements of the setting (bolters, lasguns, frag grenades, Terminator armour) can be seen in a set of earlier wargaming rules called Laserburn (produced by the now defunct company Tabletop Games) written by Bryan Ansell. These rules were later expanded by both Ansell and Richard Halliwell (both of whom ended up working for Games Workshop), although the rules were not a precursor to Rogue Trader.[32]

In addition, supplemental material was continually published in White Dwarf magazine, which provided rules for new units and models. Eventually, White Dwarf provided proper "army lists" that could be used to create larger and more coherent forces than were possible in the main rulebook. These articles were from time to time released in expansion books along with new rules, background materials and illustrations. All in all ten books were released for the original edition of Warhammer 40,000: "Chapter Approved—Book of the Astronomican", "Compendium", "Warhammer 40,000 Compilation", "Waaagh—Orks", two "Realm of Chaos" ("Slaves to Darkness" and "The Lost and the Damned"), "'Ere we Go", "Freebooterz", "Battle Manual", and "Vehicle Manual". The "Battle Manual" changed and codified the combat rules and provided updated stats for most of the weapons in the game. The "Vehicle Manual" contained a new system for vehicle management on the tabletop which was intended to supersede the clunky rules given in the base hardback manual and in the red softback compendium, it had an inventive target location system which used acetate crosshairs to simulate weapon hits on the vehicle silhouettes with different armour values for different locations (such as tracks, engine compartment, ammo store, and so on). "Waaagh—Orks" was an introductory manual to Orkish culture and physiology. It contained no rules, but background material. Other Ork-themed books instead were replete with army lists for major Ork clans and also for greenskin pirate and mercenary outfits.

Games Workshop released two important supplementary rulebooks for this edition: Realm of Chaos: Slaves to Darkness and Realm of Chaos: The Lost and the Damned. These two books added the Chaos Gods and their daemons to the setting along with the Horus Heresy origin story. In the original rulebook of 1987, the Emperor was bed-ridden due to extreme old age but could still communicate and therefore rule his empire. But with the revisions introduced in The Lost and the Damned, the Emperor became comatose, the consequence of critical injuries sustained in battle.

The artwork of the 1st edition books was a mish-mash of styles from a variety of science-fiction works, such as H. R. Giger, Star Wars, and 2000AD comics. In subsequent editions, the artwork of Warhammer 40,000 moved towards a more coherent aesthetic based around gothic architecture and art.

Second edition (1993)

The second edition of Warhammer 40,000 was published in late 1993. This new course for the game was forged under the direction of editor Andy Chambers.

Andy Chambers reshaped the lore in way that was more serious and pessimistic in tone (a direction which Rick Priestley lamented).[33] The new theme of the setting is that humanity's situation is not merely dire but hopeless, as the Imperium does not have the strength to defeat its myriad enemies and will collapse in time. This was not the case in the first edition; the first edition rulebook suggested that humanity could eventually triumph and prosper if it can survive long enough to complete its evolution into a fully psychic race, and this was the Emperor's goal.

The second edition of the game introduced army lists, putting constraints on the composition of a player's army. At least 75% of an army's strength (by point value) had to be of units from the same faction. This way, the battles that the players would play would fit the factional rivalries described in the setting. An expansion box set titled Dark Millennium was later released, which included rules for psychic powers. Another trait of the game was the attention given to "special characters" representing specific individuals from the setting, who had access to equipment and abilities beyond those of regular units; the earlier edition only had three generic "heroic" profiles for each army: "champion", "minor hero" and "major hero". A player could spend up to 50% of their army points on a special character. Such heroic characters were so powerful that the second edition was nicknamed "Herohammer".[34]

The second edition introduced major revisions to the lore and would go on to define the general character of the lore up until the 8th edition. The Adeptus Mechanicus' prohibition on artificial intelligence was added, stemming from an ancient cataclysmic war between humans and sentient machines; this was inspired by the Dune novels.

Third edition (1998)

The third edition of the game was released in 1998 and, like the second edition, concentrated on streamlining the rules for larger battles.[35] Third-edition rules were notably simpler.[36] The rulebook was available alone, or as a boxed set with miniatures of Space Marines (one 10-man Tactical Squads with a Sergeant, missile launcher, and flamer, and the redesigned Space Marine Landspeeder with a Heavy Bolter) and the newly introduced Dark Eldar (now called "Drukhari") (20 Kabalite Warriors). The system of army 'codexes' continued in third edition. The box artwork and studio army depicted the Black Templars Space Marine Chapter.

Towards the end of the third edition, four new army codexes were introduced: the xeno (that is, alien) races of the Necron and the Tau and two armies of the Inquisition: the Ordo Malleus (called Daemonhunters), and the Ordo Hereticus (called Witchhunters); elements of the latter two armies had appeared before in supplementary material (such as Realm of Chaos and Codex: Sisters of Battle). At the end of the third edition, these armies were re-released with all-new artwork and army lists. The release of the Tau coincided with a rise in popularity for the game in the United States.[37]

Fourth edition (2004)

The fourth edition of Warhammer 40,000 was released in 2004.[38] This edition did not feature as many major changes as prior editions, and was "backwards compatible" with each army's third-edition codex. The fourth edition was released in three forms: the first was a standalone hardcover version, with additional information on painting, scenery building, and background information about the Warhammer 40,000 universe. The second was a boxed set, called Battle for Macragge, which included a compact softcover version of the rules, scenery, dice, templates, and Space Marines and Tyranid miniatures. The third was a limited collector's edition. Battle for Macragge was a 'game in a box', targeted primarily at beginners. Battle for Macragge was based on the Tyranid invasion of the Ultramarines' homeworld, Macragge. An expansion to this was released called The Battle Rages On!, which featured new scenarios and units, like the Tyranid Warrior.

Fifth edition (2008)

The fifth edition of Warhammer 40,000 was released on July 12, 2008. While there are some differences between the fourth and fifth editions, the general rule set shares numerous similarities. Codex books designed prior to the fifth edition are still compatible with only some changes to how those armies function.[39] The replacement for the previous edition's Battle for Macragge starter set was called Assault on Black Reach, which featured a pocket-sized rulebook (containing the full ruleset but omitting the background and hobby sections of the full-sized rulebook), and starter armies for the Space Marines (1 Space Marine Captain, one 10-man Tactical Squad, one 5-man Terminator Squad, one Space Marine Dreadnought) and Ork (one Ork Warboss, 20 Ork Boyz, 5 Ork Nobz, 3 Ork Deffkoptas).

New additions to the rules included the ability for infantry models to "Go to Ground" when under fire, providing additional protection at the cost of mobility and shooting as they dive for cover. Actual line of sight is needed to fire at enemy models. Also introduced was the ability to run, whereby units may forgo shooting to cover more ground. In addition, cover was changed so that it is now easier for a unit to get a cover save. Damage to vehicles was simplified and significantly reduced, and tanks could ram other vehicles.[39] Some of these rules were modelled after rules that existed in the Second Edition, but were removed in the Third. Likewise, 5th edition codexes saw a return of many units that had been cut out in the previous edition for having unwieldy rules. These units were largely been brought back with most of their old rules streamlined for the new edition. Fifth edition releases focused largely on Space Marine forces, including the abolishment of the Daemonhunters in favour of an army composed of Grey Knights, a special chapter of Space Marines, which, in previous editions, had provided the elite choices of the Daemonhunters' army list. Another major change was the shift from metal figures to resin kits.

Sixth edition (2012)

Sixth edition was released on June 23, 2012. Changes to this edition included the adoption of an optional Psychic Power card system similar to that of the game's sister product Warhammer Fantasy Battle as well as the inclusion of full rules for flying vehicles and monsters and a major reworking of the manner in which damage is resolved against vehicles. It also included expanded rules for greater interaction with scenery and more dynamic close-combat.[40] In addition to updating existing rules and adding new ones, 6th Edition introduced several other large changes: the Alliance system, in which players can bring units from other armies to work with their own, with varying levels of trust; the choice to take one fortification as part of your force; and Warlord traits, which will allow a player's Commander to gain a categorically randomised trait that can aid their forces in different situations. Replacing the "Assault on Black Reach" box set was the "Dark Vengeance" box set which included Dark Angels and Chaos Space Marine models. Some of the early release box sets of Dark Vengeance contained a limited edition Interrogator-Chaplain for the Dark Angels.

The Imperial Knights (Codex: Imperial Knights) were a new addition to the Imperium of Man faction. Previously found in Epic large scale battles, particularly the Titan Legions (2nd Edition) boxed set, the Imperial Knights are walkers that are smaller than proper Imperial Titans but nonetheless tower over all other Warhammer 40,000 vehicles and troops.[41][42]

Seventh edition (2014)

The seventh edition of the game was announced in White Dwarf issue 15, pre-orders for May 17 and release date of May 24, 2014.[43]

The 7th edition saw several major changes to the game, including a dedicated Psychic Phase, as well as the way Psychic powers worked overall,[44] and changeable mid-game Tactical Objectives. Tactical Objectives would give the players alternative ways to score Victory Points, and thus win games. These objectives could change at different points during the game.[45][46]

As well as these additions, the 7th edition provided a new way to organise Army lists. Players could play as either Battle-Forged, making a list in the same way as 6th edition, or Unbound, which allowed the player to use any models they desired, disregarding the Force Organisation Chart.[47] Bonuses are given to Battle-Forged armies. Additionally, Lord of War units, which are powerful units previously only allowed in large-scale ("Apocalypse") games, are now included in the standard rulebook, and are a normal part of the Force Organisation Chart.

Eighth edition (2017)

The eighth edition of the game was announced on April 22, 2017,[48] pre-orders for June 3[49] and release date of June 17, 2017.[50]

The 8th edition was the most radical revision to Warhammer 40,000's rules since the third edition. The game introduced the Three Ways to Play concept: Open, Matched, and Narrative.[51] The core ruleset was simplified down to 14 pages, and was available as a free PDF booklet on the Games Workshop website.[52] The more complex rules are retained in the updated hardcover Rulebook. The narrative of the setting has also been updated: an enlarged Eye of Terror has split the galaxy in half,[53] while the Primarch Roboute Guilliman returns to lead the Imperium as its Lord Commander, beginning with reclaiming devastated worlds through the Indomitus Crusade.[54]

The 8th Edition introduced a new box set called "Dark Imperium", which featured the next-generation Primaris Space Marines which are available as reinforcements to existing Space Marine Chapters, as well as introducing new characters and rules to the Death Guard Chaos Space Marines.

Ninth edition (2020)

The ninth edition was released in July 2020. With it came a redesigned logo, the first redesign since 3rd edition. The 9th edition was only a minor modification of the 8th edition's rules. Codexes, supplements and the rules from the Psychic Awakening series made for 8th edition are compatible with 9th.

Ninth edition also introduced four new box sets: Indomitus, a limited release set that came out at the start of 9th edition, and the Recruit, Elite and Command editions. The four boxes feature revised designs and new units for the Necrons, and new units for the Primaris Space Marines.

Supplements and expansions

There are many variations to the rules and army lists that are available for use, typically with an opponent's consent.[55] These rules are found in the Games Workshop publication White Dwarf, on the Games Workshop website, or in the Forge World Imperial Armour publications.

The rules of Warhammer 40,000 are designed for games between 500 and 3000 points, with the limits of a compositional framework called the Force Organisation Chart making games with larger point values difficult to play. In response to player comments, the Apocalypse rules expansion was introduced to allow 3000+ point games to be played. Players might field an entire 1000-man Chapter of Space Marines rather than the smaller detachment of around 30–40 typically employed in a standard game. Apocalypse also contains rules for using larger war machines such as Titans. The latest rules for Apocalypse based on the Warhammer 40,000 rules are found in Chapter Approved 2017, while a boxed set also entitled Apocalypse with an entirely different rules base was released in 2019.

Cities of Death (the revamp of Codex Battlezone: Cityfight) introduces rules for urban warfare and guerrilla warfare, and so-called "stratagems", including traps and fortifications. It also has sections on modelling city terrain and provides examples of armies and army lists modeled around the theme of urban combat. This work was updated to 7th Edition with the release of Shield of Baal: Leviathan[56] and to 8th edition in Chapter Approved 2018.

Planetstrike, released 2009, sets rules allowing players to represent the early stages of a planetary invasion. It introduces new game dynamics, such as dividing the players into an attacker and a defender, each having various tactical benefits tailored to their role; for example, the attacker may deep strike all infantry, jump infantry and monstrous creatures onto the battlefield, while the defender may set up all the terrain on the battlefield. Planetstrike was updated to the 8th edition of the game in Chapter Approved 2017.

Planetary Empires, released August 2009, allows players to coordinate full-scale campaigns containing multiple battles, each using standard rules or approved supplements such as Planetstrike, Cities of Death or Apocalypse. Progress through the campaign is tracked using hexagonal tiles to represent the current control of territories within the campaign. The structure is similar to Warhammer Fantasy's Mighty Empires. The set has been out of production for many years.

Battle Missions, released March 2010, this expansion contained a series of 'missions' with specific objectives, each 'race' has three specific missions which can be played, these missions are determined by a dice roll and are usually chosen from the two armies being used. They still used the standard rules from the Warhammer 40,000 rule book. The Battle Missions format was never updated for 8th or 9th editions and is no longer compatible with the current iteration of the game.

Spearhead, released May 2010, allowed players to play games with a greater emphasis on armoured and mechanised forces. The most notable change to the game is the inclusion of special "Spearhead Formations;" and greater flexibility in force organisation. "Spearhead Formations" represent a new and altogether optional addition to the force organisation system standard to Warhammer 40,000. Players now have the ability to use all, part or none of the standard force organisation. Spearhead also includes new deployment options and game scenarios. This expansion was being released jointly through the Games Workshop website, as a free download, and through the company's monthly hobby magazine White Dwarf. The Spearhead rules were never updated for 8th or 9th editions and are no longer compatible with the current iteration of the game, though the loosened force organization introduced in 8th edition makes them somewhat superfluous.

Death from the Skies, released February 2013, contains rules for playing games with an emphasis on aircraft. There are specific rules for each race's aircraft, as well as playable missions. A notable inclusion in this release is "warlord traits" for each race that deal specifically with aircraft. This supplement still uses the same rules as the Warhammer 40,000 rulebook. Got updated to 7th Edition with Shield of Baal: Leviathan. Death From the Skies was not updated post-7th edition, but 8th edition and onward permits using aircraft in the core rules.

Stronghold Assault, released in December 2013, was a 48-page expansion that contains more rules for fortifications in the game, as well as rules for more fortifications than listed in the main 6th Edition Rulebook. Stronghold Assault was updated for the 8th edition of the game in Chapter Approved 2017.

Escalation, released December 2013, contained rules for playing games with super heavy vehicles, normally restricted to Apocalypse events, in normal events. Escalation was not updated, and in the current iteration of the game super heavy vehicles can be used in the core rules.

Spin-off games, novels, and other media

Games Workshop has expanded the Warhammer 40,000 universe over the years to include several spin-off games and fictional works. This expansion began in 1987, when Games Workshop asked Scott Rohan to write the first series of "literary tie-ins". This eventually led to the creation of Black Library, the publishing arm of Games Workshop, in 1997. The books published relate centrally to the backstory in the Warhammer universe. Black Library also publishes Warhammer 40,000 graphic novels.[57]

Several popular miniature game spin-offs were created, including Space Crusade, Space Hulk, Kill Team, Battlefleet Gothic, Epic 40,000, Inquisitor, Gorkamorka, Necromunda and Assassinorum: Execution Force. A collectible card game, Dark Millennium, was launched in October 2005 by Games Workshop subsidiary, Sabertooth Games. The story behind the card game begins at the end of the Horus Heresy arc in the game storyline and contains four factions: the Imperium, Orks, Aeldari and Chaos.[58]

Music

The album Realms of Chaos: Slaves to Darkness by British death metal band Bolt Thrower features lyrics as well as artwork based on the Warhammer and Warhammer 40,000 brands, with the album's title design being identical to that of the eponymous Games Workshop books.

In the early 1990s Games Workshop set up their own label, Warhammer Records. The band D-Rok were signed to this label; their only album, Oblivion, featured songs based on Warhammer 40,000.

Novels

Following the 1987 initial release of Games Workshop's Warhammer 40,000 wargame the company began publishing background literature that expands previous material, adds new material, and describes the universe, its characters, and its events in detail. Since 1997 the bulk of background literature has been published by the affiliated imprint Black Library.

The increasing number of fiction works by an expanding list of authors is published in several formats and media, including audio, digital and print. Most of the works, which include full-length novels, novellas, short stories, graphic novels, and audio dramas, are parts of named book series. In 2018, a line of novels for readers aged 8 to 12 was announced, which led to some confusion among fans given the ultra-violent and grimdark nature of the setting.[59]

Video games

Games Workshop first licensed Electronic Arts to produce Warhammer 40,000 video-games, and EA published two games based on Space Hulk in 1993 and 1995. Games Workshop then passed the license to Strategic Simulations, which published three games in the late 1990s. After Strategic Simulations went defunct in 1994, Games Workshop then gave the license to THQ, and between 2003 and 2011 THQ published 13 games, which include the Dawn of War series. After 2011, Games Workshop changed its licensing strategy: instead of an exclusive license to a single publisher, it broadly licenses a variety of publishers.[60]

Board games and role-playing games

Games Workshop have produced a number of standalone "boxed games" set within the Warhammer 40,000 setting; they have licensed the intellectual property to other game companies such as Fantasy Flight Games. The Games Workshop-produced boxed games tend to be sold under the aegis of the "Specialist Games" division. Titles include:

- Battle for Armageddon

- Chaos Attack (Expansion for Battle for Armageddon)

- Doom of the Eldar

- Space Hulk (Four editions were published; expansions are listed below.)

- Deathwing (An expansion boxed set adding new Terminator weapons and a new campaign.)

- Genestealer (An expansion boxed set adding rules for Genestealer hybrids and psychic powers.)

- Space Hulk Campaigns (An expansion book released in both soft and hard-cover collecting reprinted four campaigns previously printed in White Dwarf.)

- Advanced Space Crusade

- Assassinorum: Execution Force

- Bommerz over da Sulphur River (Board game using Epic miniatures.)

- Gorkamorka (A vehicle skirmish game set on a desert world, revolving principally around rival Ork factions.)

- Digganob (An expansion for Gorkamorka, adding rebel gretchin and feral human factions.)

- Lost Patrol

- Space Fleet (A simple spaceship combat game, later greatly expanded via White Dwarf magazine with material intended for the aborted 'Battleship Gothic', itself later relaunched as Battlefleet Gothic.)

- Tyranid Attack (An introductory game reusing the boards from Advanced Space Crusade.)

- Ultra Marines (An introductory game reusing the boards from Space Hulk.)

- Blackstone Fortress (A cooperative board game set in the wreck of a large spaceship known as a Blackstone Fortress, using the previously Warhammer Fantasy-based Warhammer Quest system)

Although there were plans to create a full-fledged Warhammer 40,000 "pen and paper" role-playing game from the beginning,[61] these did not come to fruition for many years, until an official Warhammer 40,000 role-playing game was published only in 2008, with the release of Dark Heresy by Black Industries, a Games Workshop subsidiary. This system was later licensed to Fantasy Flight Games for continued support and expansion.

Formerly Games Workshop licensed a number of Warhammer 40K themed products to Fantasy Flight Games. They specialise in board, card and role-playing games. Included in the licensed product were:

- Horus Heresy: a board game focusing on the final battle of the Horus Heresy the battle for the Emperor's Palace; this game is a re-imagining of a game by the same name created by Jervis Johnson in the 1990s.

- Space Hulk: Death Angel, The Card Game: the card game version of Space Hulk. Players cooperate as Space Marines in order to clear out the infestation of Genestealers on a derelict spaceship.

- Warhammer 40,000: Conquest: a Living Card Game where players control various factions of the Warhammer 40,000 setting in order to rule the sector.

- Forbidden Stars: a board game that pits 4 popular Warhammer 40,000 races against one another to control objectives and secure the sector for themselves.

- Relic: an adaptation of the board game Talisman to the Warhammer: 40,000 setting.

- The Warhammer 40,000 Roleplay series of tabletop role-playing games, which share many core mechanics as well as the setting:

- Dark Heresy: players may assume the roles of a cell of Inquisitorial acolytes, or assume a different and equally small-scale scenario following the game's rules. The recommended scenarios and ruleset present a balance between investigation and combat encounters.

- Rogue Trader: players assume the roles of Explorers, whose rank and escalated privileges allow for travelling outside the Imperium's borders. Due to extensive expansions for Rogue Trader, campaigns can be largely different and altered by game masters. Its most significant difference from any of the other Warhammer 40,000 Roleplay titles is that it contains rules for capital spaceship design and space combat.

- Deathwatch: the game allows players to role-play the Space Marines of the Adeptus Astartes, who are the gene-enhanced superhuman elite combat units of the Imperium of Man. In light of this, its ruleset heavily emphasises combat against difficult or numerically superior enemies, rather than negotiation and investigation, compared to Dark Heresy or Rogue Trader.

- Black Crusade: Black Crusade allows players to role-play Chaos-corrupted characters. This instalment will be concluded with supplements. It is notably different in that it allows much more free-form character development, with experience costs being determined by affiliation with a Chaos God.

- Only War: Only War puts players in the boots of the Imperial Guard, the foot soldiers of the Imperium of Man. Despite the human-level capabilities of the characters, it also emphasises combat over interaction, much like Deathwatch.

Games from other publishers include:

- Risk: Warhammer 40,000: This is a 40K-themed variant of the board game Risk, published by The OP.[62]

- Monopoly: Warhammer 40,000: A 40K-themed version of the board game Monopoly, published by The OP.[63]

- Munchkin Warhammer 40,000: a 40K-themed edition of Munchkin, released in 2019 by Steve Jackson Games.[64]

- Magic: the Gathering Universes Beyond: Warhammer 40,000 collaboration: A series of 40k-themed pre-constructed decks and limited edition collections of Magic: the Gathering.[65]

Film

On December 13, 2010,[66] Ultramarines: A Warhammer 40,000 Movie was released directly to DVD. It is a CGI science fiction film, based around the Ultramarines Chapter of Space Marines. The screenplay was written by Dan Abnett, a Games Workshop Black Library author. The film was produced by Codex Pictures, a UK-based company, under license from Games Workshop. It utilised animated facial capture technology from Image Metrics.

TV

On July 17, 2019, Games Workshop and Big Light Productions announced the development of a live-action TV series based on the character Gregor Eisenhorn, who is an Imperial Inquisitor.[67] Frank Spotnitz will be the showrunner for the series. The series is expected to be based on the novels written by Dan Abnett.[68]

Reviews

- Backstab #12 (third edition)[69]

Awards

Warhammer 40,000 2nd Edition won the 1993 Origins Award for Best Miniatures Rules.[70]

In 2003, Warhammer 40,000 was inducted into the Origins Hall of Fame.[71]

Warhammer 40,000 8th Edition won the 2017 Origins Awards for Best Miniatures Game and Fan Favorite Miniatures Game.[72]

References

Explanatory notes

- Sometimes referred to colloquially as Warhammer 40K or WH40K

Citations

- "Top 5 Non-Collectible Miniature Games—Spring 2019". icv2.com. 31 July 2019. Archived from the original on 7 November 2020. Retrieved 19 August 2019.

- "Top 5 Non-Collectible Miniature Games—Spring 2020". icv2.com. 12 August 2020. Archived from the original on 19 September 2021. Retrieved 29 October 2020.

- Edison Investment Research (10 April 2019). "On a Mission". www.edisongroup.com. Archived from the original on 21 February 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

This market analysis does not break down sales figures between specific product lines, but it adds partial validity to the claim that Warhammer 40,000 is most popular among the British, where Games Workshop's sales are strongest in general. - Ahmed, Samira (13 March 2012). "Why are adults still launching tabletop war?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2018-10-13. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

The prices for essential models, paints and books are 'eyewatering', he says. [...] 'You need at least £200 just to set up a half-decent legal army for a game, and if you want a board and scenery to go to play with friends you're looking at least £200 on top of that,' says Craig Lowdon, 25, of Crewe.

- "Britons are increasingly turning to tabletop games for entertainment". The Economist. 4 Oct 2018. Archived from the original on 2018-10-13. Retrieved 2018-10-12.

For years, Games Workshop was known primarily for two things: pricey products (a Warhammer army can cost well over £300, or $390)

- Carter et al. (2014)

- Scale Model Kits for 40K Archived 2018-10-12 at the Wayback Machine. www.dakkadakka.com.

- Warhammer 40,000 (core rulebook, 9th edition), p 238

- "Model Requirements for events at Warhammer World" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-01-18. Retrieved 2022-02-02.

- Baer, Rob (2021-05-26). "Games Workshop Opens the War Against 3D Artists". Spikey Bits. Retrieved 2022-07-13.

- Warhammer 40,000 (core rulebook, 8th ed.), p 214

- Warhammer 40,000: Index: Imperium 1 (8th ed.), p 202

- Warhammer 40,000 (core rulebook, 8th ed.)

- Warhammer 40,000 (core rulebook, 8th ed.), p. 181

- Warhammer 40,000 (core rulebook 8th ed.), p. 178

- Aaron Dembski-Bowden (2017). Master of Mankind, Afterword

- Roberts, Adam (2014). Get Started in: Writing Science Fiction and Fantasy. Hachette UK. p. 42. ISBN 9781444795660. Archived from the original on 2015-05-22. Retrieved 2020-04-08.

- Warhammer 40,000: Rogue Trader (1987). pg 146.

- Duffy, Owen (11 December 2015). "Blood, dice and darkness: how Warhammer defined gaming for a generation". Cardboard Sandwich. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016.

'Bryan's idea of Chaos was very much derived from [science fiction and fantasy author] Michael Moorcock,' he said. 'I always thought it was a little too close for comfort, it looked like we were just copying.'

'But I'd always had this sense of Chaos existing as described in Paradise Lost. I’d tried to bring elements of that into the background and gradually change it from a description of demons into a kind of force out of which came realities, a kind of literal primal chaos.'

“'Unless you've read Paradise Lost you don't get it. The whole Horus Heresy is just a parody of the fall of Lucifer as described by Milton.' - Q&A with Rick Priestley (Reddit.com) Archived 2019-03-04 at the Wayback Machine: "...that's the essence of chaos—its physic energy shaped by the human unconsciousness—it is not good/bad—but likewise it is not logical—it is Monsters from the Id in the same sense as in Forbidden Planet"

- Duffy, Owen (11 December 2015). "Blood, dice and darkness: how Warhammer defined gaming for a generation". Cardboard Sandwich. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016.

- "Warhammer 40,000 Faction Focus—Necrons". TheGamer. 2020-07-22. Archived from the original on 2022-02-21. Retrieved 2021-02-24.

- Warhammer 40,000 Index: Xenos 2 p. 10

- Warhammer 40,000: Index: Xenos 2 p 85

- White Dwarf #114 (1989), pp. 31–36

- A pulse rifle has a Strength score of 5 whereas a boltgun has a Strength score of 4. See Index: Imperium 1 and Index: Xenos 2 (8th edition).

- "Interview with Rick Priestley". Juegos y Dados. 26 August 2016. Archived from the original on 20 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- Rolston, Ken (January 1988). "Advanced hack-and-slash" (PDF). Dragon. TSR, Inc. (129): 86–87. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-12-25. Retrieved 2021-12-25.

- "Warhammer 40,000". White Dwarf. No. 93. Games Workshop. September 1987. pp. 33–44.

- Priestley, Rick (1987) [1992]. Rogue Trader. Eastwood: Games Workshop. ISBN 1-872372-27-9.

- "The High Lords Speak". White Dwarf (UK Edition). Games Workshop (343): 35–36. June 2008.

- White Dwarf (June, 2008) pp. 34–35

- James Maliszewski (13 November 2020). "Interview: Rick Priestley (Part II)". Grognardia. Archived from the original on 7 May 2021. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- "Warhammer 40K: A History of Editions—1st & 2nd Edition". 25 March 2020. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- Priestley, Rick; et al. (1998). Warhammer 40,000 (3rd ed.). Nottingham: Games Workshop. ISBN 1-84154-000-5.

- Driver, Jason. "Warhammer 40K, 3rd edition". RPGnet. Skotos Tech. Archived from the original on 2012-02-24. Retrieved 2008-09-29.

- Guthrie, Jonathon (July 31, 2002). "Games Workshop runs rings around its rivals". Financial Times. p. 20. ProQuest 249274306.

- Chambers, Andy; Priestley, Rick; Haines, Pete (2004). Warhammer 40,000 (4th ed.). Nottingham: Games Workshop. ISBN 1-84154-468-X.

- "in the Pipeline". White Dwarf (UK) (343). July 2008.

- "Games Workshop". Archived from the original on 2012-06-25. Retrieved 2012-06-22.

- "Warhammer 40,000 6th Edition Rulebook—Warhammer 40k". Lexicanum. Archived from the original on 2021-02-25. Retrieved 2021-02-06.

- "Start Competing: Imperial Knights Tactics". Goonhammer. 27 September 2019. Archived from the original on 2022-01-31. Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- Harden, Dan. "White Dwarf, the herald of things to come…". Games Workshop. Archived from the original on 2 June 2014. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- NEW! Warhammer 40,000: The Psychic Phase. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-06-26 – via YouTube.

- NEW! Warhammer 40,000: Maelstrom of War Missions. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-05-14 – via YouTube.

- "Warhammer 40,000: Tactical Objectives". Games Workshop Webstore. Archived from the original on 2014-06-07.

- NEW! Warhammer 40,000: New army organisation options. 16 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-05-12 – via YouTube.

- "Breaking News!". Warhammer Community. 2017-04-22. Archived from the original on 2017-07-07. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- "Dark Imperium Pre-orders". Warhammer Community. 2017-06-03. Archived from the original on 2017-07-10. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- "New Edition Now Available—Read the Rules, Get the T-Shirt!". Warhammer Community. 2017-06-17. Archived from the original on 2017-07-05. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- "New Warhammer 40,000: Three Ways to Play". Warhammer Community. 2017-04-24. Archived from the original on 2017-07-10. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- "Rules". Games Workshop. Archived from the original on 2017-08-01. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- "New Warhammer 40,000: The Galaxy Map". Warhammer Community. 2017-04-23. Archived from the original on 2017-11-07. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- Guy, Haley (2018). DARK IMPERIUM. [S.l.]: GAMES WORKSHOP LTD. ISBN 9781784966645. OCLC 989984121.

- Priestley, Rick; et al. (1998) pp. 270–272

- Hoare, Andy (2006). Cities of Death. Nottingham: Games Workshop. ISBN 1-84154-749-2.

- Baxter, Stephen (2006). "Freedom in an Owned World: Warhammer Fiction and the Interzone Generation". Vector: The Critical Journal of the British Science Fiction Association. British Science Fiction Association. 229. Archived from the original on 2012-02-16.

- Kaufeld, John; Smith, Jeremy (2006). Trading Card Games For Dummies. For Dummies. pp. 186. ISBN 978-0-471-75416-9.

- Hall, Charlie (22 May 2018). "Warhammer 40,000 is launching a line of young adult fiction and fans are confused". Polygon. Archived from the original on 22 May 2018. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: The Warhammer 40k License—A Total Change of Strategy. Extra Credits. June 8, 2016 – via YouTube.

- Edwards, Darren (1988). "Interview with Rick Priestley". Making Movies (3): 17.

- Meehan, Alex (23 April 2020). "Risk: Warhammer 40,000 is marching onto shelves this autumn". Dicebreaker. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Jonathan Bolding (2018-07-13). "Warhammer 40k Monopoly is a thing now, because of course it is". PC Gamer. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- "Munchkin Warhammer 40.000 - Rezension Kartenspiel". roterdorn - Das Medienportal (in German). Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- Kaplan, Billie. "A First Look at Magic: The Gathering's Universes Beyond Warhammer 40,000 Collaboration". magic.wizards.com. Wizards of the Coast. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- "Ultramarines: A Warhammer 40,000 Movie (2010)". Sci-Fi Movie Page. Archived from the original on 2020-02-23. Retrieved 2010-12-19.

- "Heretic, Traitor, Rogue, Inquisitor… TV Star?". Warhammer Community. 2019-07-17. Archived from the original on 2019-07-19. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- Clarke, Stewart (2019-07-17). "'Eisenhorn' Series Based on 'Warhammer 40,000' in the Works from Frank Spotnitz". Variety. Archived from the original on 2019-07-18. Retrieved 2019-07-19.

- Jason Scott. "Backstab Magazine (French) Issue 12 : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive". Retrieved 2022-02-21.

- "List of Winners". Origins Game Fair. Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts & Design. Archived from the original on 2008-03-07.

- "The 2003 Origins Awards—Presented at Origins 2004". Game Manufacturers Association. Archived from the original on 2012-12-16.

- Griepp, Milton (June 18, 2018). "2018 Origins Award Winners". ICv2. Archived from the original on June 29, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

General and cited references

- Warhammer 40,000 Core Rules (free PDF)

- Marcus Carter; Martin Gibbs; Mitchell Harrop (2014). "Drafting an Army: The Playful Pastime of Warhammer 40,000". Games and Culture. 9 (2): 122–147. doi:10.1177/1555412013513349. S2CID 61280574.