Nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm that possess many exclusive functions and characteristics. The characteristics associated with nobility may constitute substantial advantages over or relative to non-nobles or simply formal functions (e.g., precedence), and vary by country and by era. Membership in the nobility, including rights and responsibilities, is typically hereditary and patrilineal.

| Part of a series on |

| Imperial, royal, noble, gentry and chivalric ranks in Europe |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Emperor · Empress (dowager) · Tsar · Tsarina · High king · High queen |

| King (regnant · consort · dowager) · Queen (regnant · consort · dowager · mother) · Grand duke · Grand duchess · Archduke · Archduchess |

| Prince (consort) · Princess (consort) · Duke · Duchess · Crown prince · Crown princess · Jarl · Prince-elector · Princess-elector |

| Marquess · Marchioness · Margrave · Margravine · Count palatine · Voivode |

| Count · Countess · Earl · Ealdorman |

| Viscount · Viscountess · Castellan · Burgrave · Burgravine · Advocatus · Vidame · Starosta |

| Baron · Baroness · Thane · Lendmann · Primor · Boyar |

| Baronet · Baronetess · Lord of the Manor |

| Knight · Chevalier · Eques · Imperial Knight · Druzhinnik |

| Esquire · Gentleman · Gentlewoman · Ministerialis |

Membership in the nobility has historically been granted by a monarch or government, and acquisition of sufficient power, wealth, ownerships, or royal favour has occasionally enabled commoners to ascend into the nobility.[1]

There are often a variety of ranks within the noble class. Legal recognition of nobility has been much more common in monarchies, but nobility also existed in such regimes as the Dutch Republic (1581–1795), the Republic of Genoa (1005–1815), the Republic of Venice (697–1797), and the Old Swiss Confederacy (1300–1798), and remains part of the legal social structure of some small non-hereditary regimes, e.g., San Marino, and the Vatican City in Europe. In Classical Antiquity, the nobiles (nobles) of the Roman Republic were families descended from persons who had achieved the consulship. Those who belonged to the hereditary patrician families were nobles, but plebeians whose ancestors were consuls were also considered nobiles. In the Roman Empire, the nobility were descendants of this Republican aristocracy. While ancestry of contemporary noble families from ancient Roman nobility might technically be possible, no well-researched, historically-documented generation-by-generation genealogical descents from ancient Roman times are known to exist in Europe.

Hereditary titles and styles added to names (such as "Prince", "Lord", or "Lady"), as well as honorifics, often distinguish nobles from non-nobles in conversation and written speech. In many nations, most of the nobility have been untitled, and some hereditary titles do not indicate nobility (e.g., vidame). Some countries have had non-hereditary nobility, such as the Empire of Brazil or life peers in the United Kingdom.

History

The term derives from Latin nobilitas, the abstract noun of the adjective nobilis ("noble but also secondarily well-known, famous, notable").[2] In ancient Roman society, nobiles originated as an informal designation for the political governing class who had allied interests, including both patricians and plebeian families (gentes) with an ancestor who had risen to the consulship through his own merit (see novus homo, "new man").

In modern usage, "nobility" is applied to the highest social class in pre-modern societies.[3] In the feudal system (in Europe and elsewhere), the nobility were generally those who held a fief, often land or office, under vassalage, i.e., in exchange for allegiance and various, mainly military, services to a suzerain, who might be a higher-ranking nobleman or a monarch. It rapidly became a hereditary caste, sometimes associated with a right to bear a hereditary title and, for example in pre-revolutionary France, enjoying fiscal and other privileges.

While noble status formerly conferred significant privileges in most jurisdictions, by the 21st century it had become a largely honorary dignity in most societies,[4] although a few, residual privileges may still be preserved legally (e.g., Netherlands, Spain, UK) and some Asian, Pacific and African cultures continue to attach considerable significance to formal hereditary rank or titles. (Compare the entrenched position and leadership expectations of the nobility of the Kingdom of Tonga.) More than a third of British land is in the hands of aristocrats and traditional landed gentry.[5][6]

Nobility is a historical, social and often legal notion, differing from high socio-economic status in that the latter is mainly based on income, possessions or lifestyle. Being wealthy or influential cannot ipso facto make one noble, nor are all nobles wealthy or influential (aristocratic families have lost their fortunes in various ways, and the concept of the 'poor nobleman' is almost as old as nobility itself).

Although many societies have a privileged upper class with substantial wealth and power, the status is not necessarily hereditary and does not entail a distinct legal status, nor differentiated forms of address. Various republics, including European countries such as Greece, Turkey, Austria and former Iron Curtain countries and places in the Americas such as Mexico and the United States, have expressly abolished the conferral and use of titles of nobility for their citizens. This is distinct from countries which have not abolished the right to inherit titles, but which do not grant legal recognition or protection to them, such as Germany and Italy, although Germany recognizes their use as part of the legal surname. Still other countries and authorities allow their use, but forbid attachment of any privilege thereto, e.g., Finland, Norway and the European Union, while French law also protects lawful titles against usurpation.

Noble privileges

Not all of the benefits of nobility derived from noble status per se. Usually privileges were granted or recognized by the monarch in association with possession of a specific title, office or estate. Most nobles' wealth derived from one or more estates, large or small, that might include fields, pasture, orchards, timberland, hunting grounds, streams, etc. It also included infrastructure such as castle, well and mill to which local peasants were allowed some access, although often at a price. Nobles were expected to live "nobly", that is, from the proceeds of these possessions. Work involving manual labor or subordination to those of lower rank (with specific exceptions, such as in military or ecclesiastic service) was either forbidden (as derogation from noble status) or frowned upon socially. On the other hand, membership in the nobility was usually a prerequisite for holding offices of trust in the realm and for career promotion, especially in the military, at court and often the higher functions in the government, judiciary and church.

Prior to the French Revolution, European nobles typically commanded tribute in the form of entitlement to cash rents or usage taxes, labor or a portion of the annual crop yield from commoners or nobles of lower rank who lived or worked on the noble's manor or within his seigneurial domain. In some countries, the local lord could impose restrictions on such a commoner's movements, religion or legal undertakings. Nobles exclusively enjoyed the privilege of hunting. In France, nobles were exempt from paying the taille, the major direct tax. Peasants were not only bound to the nobility by dues and services, but the exercise of their rights was often also subject to the jurisdiction of courts and police from whose authority the actions of nobles were entirely or partially exempt. In some parts of Europe the right of private war long remained the privilege of every noble.[7]

During the early Renaissance, duelling established the status of a respectable gentleman, and was an accepted manner of resolving disputes.[8]

Since the end of World War I the hereditary nobility entitled to special rights has largely been abolished in the Western World as intrinsically discriminatory, and discredited as inferior in efficiency to individual meritocracy in the allocation of societal resources.[9] Nobility came to be associated with social rather than legal privilege, expressed in a general expectation of deference from those of lower rank. By the 21st century even that deference had become increasingly minimized. In general, the present nobility present in the European monarchies has no more privileges than the citizens decorated in republics.

Ennoblement

In France, a seigneurie (lordship) might include one or more manors surrounded by land and villages subject to a noble's prerogatives and disposition. Seigneuries could be bought, sold or mortgaged. If erected by the crown into, e.g., a barony or countship, it became legally entailed for a specific family, which could use it as their title. Yet most French nobles were untitled ("seigneur of Montagne" simply meant ownership of that lordship but not, if one was not otherwise noble, the right to use a title of nobility, as commoners often purchased lordships). Only a member of the nobility who owned a countship was allowed, ipso facto, to style himself as its comte, although this restriction came to be increasingly ignored as the ancien régime drew to its close.

In other parts of Europe, sovereign rulers arrogated to themselves the exclusive prerogative to act as fons honorum within their realms. For example, in the United Kingdom royal letters patent are necessary to obtain a title of the peerage, which also carries nobility and formerly a seat in the House of Lords, but never came with automatic entail of land nor rights to the local peasants' output.

Rank within the nobility

Nobility might be either inherited or conferred by a fons honorum. It is usually an acknowledged preeminence that is hereditary, i.e. the status descends exclusively to some or all of the legitimate, and usually male-line, descendants of a nobleman. In this respect, the nobility as a class has always been much more extensive than the primogeniture-based titled nobility, which included peerages in France and in the United Kingdom, grandezas in Portugal and Spain, and some noble titles in Belgium, Italy, the Netherlands, Prussia and Scandinavia. In Russia, Scandinavia and non-Prussian Germany, titles usually descended to all male-line descendants of the original titleholder, including females. In Spain, noble titles are now equally heritable by females and males alike. Noble estates, on the other hand, gradually came to descend by primogeniture in much of western Europe aside from Germany. In Eastern Europe, by contrast, with the exception of a few Hungarian estates, they usually descended to all sons or even all children.[10]

In France, some wealthy bourgeois, most particularly the members of the various parlements, were ennobled by the king, constituting the noblesse de robe. The old nobility of landed or knightly origin, the noblesse d'épée, increasingly resented the influence and pretensions of this parvenu nobility. In the last years of the ancien régime the old nobility pushed for restrictions of certain offices and orders of chivalry to noblemen who could demonstrate that their lineage had extended "quarterings", i.e. several generations of noble ancestry, to be eligible for offices and favours at court along with nobles of medieval descent, although historians such as William Doyle have disputed this so-called "Aristocratic Reaction".[11] Various court and military positions were reserved by tradition for nobles who could "prove" an ancestry of at least seize quartiers (16 quarterings), indicating exclusively noble descent (as displayed, ideally, in the family's coat of arms) extending back five generations (all 16 great-great grandparents).

This illustrates the traditional link in many countries between heraldry and nobility; in those countries where heraldry is used, nobles have almost always been armigerous, and have used heraldry to demonstrate their ancestry and family history. However, heraldry has never been restricted to the noble classes in most countries, and being armigerous does not necessarily demonstrate nobility. Scotland, however, is an exception.[12] In a number of recent cases in Scotland the Lord Lyon King of Arms has controversially (vis-à-vis Scotland's Salic law) granted the arms and allocated the chiefships of medieval noble families to female-line descendants of lords, even when they were not of noble lineage in the male line, while persons of legitimate male-line descent may still survive (e.g. the modern Chiefs of Clan MacLeod).

In some nations, hereditary titles, as distinct from noble rank, were not always recognised in law, e.g., Poland's Szlachta. European ranks of nobility lower than baron or its equivalent, are commonly referred to as the petty nobility, although baronets of the British Isles are deemed titled gentry. Most nations traditionally had an untitled lower nobility in addition to titled nobles. An example is the landed gentry of the British Isles.[13][14] Unlike England's gentry, the Junkers of Germany, the noblesse de robe of France, the hidalgos of Spain and the nobili of Italy were explicitly acknowledged by the monarchs of those countries as members of the nobility, although untitled. In Scandinavia, the Benelux nations and Spain there are still untitled as well as titled families recognised in law as noble.

In Hungary members of the nobility always theoretically enjoyed the same rights. In practice, however, a noble family's financial assets largely defined its significance. Medieval Hungary's concept of nobility originated in the notion that nobles were "free men", eligible to own land.[15] This basic standard explains why the noble population was relatively large, although the economic status of its members varied widely. Untitled nobles were not infrequently wealthier than titled families, while considerable differences in wealth were also to be found within the titled nobility. The custom of granting titles was introduced to Hungary in the 16th century by the House of Habsburg. Historically, once nobility was granted, if a nobleman served the monarch well he might obtain the title of baron, and might later be elevated to the rank of count. As in other countries of post-medieval central Europe, hereditary titles were not attached to a particular land or estate but to the noble family itself, so that all patrilineal descendants shared a title of baron or count (cf. peerage). Neither nobility nor titles could be transmitted through women.[16]

Some con artists sell fake titles of nobility, often with impressive-looking documentation. This may be illegal, depending on local law. They are more often illegal in countries that actually have nobilities, such as European monarchies. In the United States, such commerce may constitute actionable fraud rather than criminal usurpation of an exclusive right to use of any given title by an established class.

Other terms

"Aristocrat" and "aristocracy", in modern usage, refer colloquially and broadly to persons who inherit elevated social status, whether due to membership in the (formerly) official nobility or the monied upper class.

Blue blood is an English idiom recorded since 1811 in the Annual Register [17] and in 1834 [18] for noble birth or descent; it is also known as a translation of the Spanish phrase sangre azul, which described the Spanish royal family and high nobility who claimed to be of Visigothic descent,[19] in contrast to the Moors.[20] The idiom originates from ancient and medieval societies of Europe and distinguishes an upper class (whose superficial veins appeared blue through their untanned skin) from a working class of the time. The latter consisted mainly of agricultural peasants who spent most of their time working outdoors and thus had tanned skin, through which superficial veins appear less prominently.

Robert Lacey explains the genesis of the blue blood concept:

It was the Spaniards who gave the world the notion that an aristocrat's blood is not red but blue. The Spanish nobility started taking shape around the ninth century in classic military fashion, occupying land as warriors on horseback. They were to continue the process for more than five hundred years, clawing back sections of the peninsula from its Moorish occupiers, and a nobleman demonstrated his pedigree by holding up his sword arm to display the filigree of blue-blooded veins beneath his pale skin—proof that his birth had not been contaminated by the dark-skinned enemy.[21]

Africa

Africa has a plethora of ancient lineages in its various constituent nations. Some, such as the numerous sharifian families of North Africa, the Keita dynasty of Mali, the Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia, the De Souza family of Benin and the Sherbro Tucker clan of Sierra Leone, claim descent from notables from outside of the continent. Most, such as those composed of the descendants of Shaka and Moshoeshoe of Southern Africa, belong to peoples that have been resident in the continent for millennia. Generally their royal or noble status is recognized by and derived from the authority of traditional custom. A number of them also enjoy either a constitutional or a statutory recognition of their high social positions.

Ethiopia

Ethiopia has a nobility that is almost as old as the country itself. Throughout the history of the Ethiopian Empire most of the titles of nobility have been tribal or military in nature. However the Ethiopian nobility resembled its European counterparts in some respects; until 1855, when Tewodros II ended the Zemene Mesafint its aristocracy was organised similarly to the feudal system in Europe during the Middle Ages. For more than seven centuries, Ethiopia (or Abyssinia, as it was then known) was made up of many small kingdoms, principalities, emirates and imamates, which owed their allegiance to the nəgusä nägäst (literally "King of Kings"). Despite its being a Christian monarchy, various Muslim states paid tribute to the emperors of Ethiopia for centuries: including the Adal Sultanate, the Emirate of Harar, and the Awsa sultanate.

Ethiopian nobility were divided into two different categories: Mesafint ("prince"), the hereditary nobility that formed the upper echelon of the ruling class; and the Mekwanin ("governor") who were appointed nobles, often of humble birth, who formed the bulk of the nobility (cf. the Ministerialis of the Holy Roman Empire). In Ethiopia there were titles of nobility among the Mesafint borne by those at the apex of medieval Ethiopian society. The highest royal title (after that of emperor) was Negus ("king") which was held by hereditary governors of the provinces of Begemder, Shewa, Gojjam, and Wollo. The next highest seven titles were Ras, Dejazmach, Fit'awrari, Grazmach, Qenyazmach, Azmach and Balambaras. The title of Le'ul Ras was accorded to the heads of various noble families and cadet branches of the Solomonic dynasty, such as the princes of Gojjam, Tigray, and Selalle. The heirs of the Le'ul Rases were titled Le'ul Dejazmach, indicative of the higher status they enjoyed relative to Dejazmaches who were not of the blood imperial. There were various hereditary titles in Ethiopia: including that of Jantirar, reserved for males of the family of Empress Menen Asfaw who ruled over the mountain fortress of Ambassel in Wollo; Wagshum, a title created for the descendants of the deposed Zagwe dynasty; and Shum Agame, held by the descendants of Dejazmach Sabagadis, who ruled over the Agame district of Tigray. The vast majority of titles borne by nobles were not, however, hereditary.

Despite being largely dominated by Christian elements, some Muslims obtained entrée into the Ethiopian nobility as part of their quest for aggrandizement during the 1800s. To do so they were generally obliged to abandon their faith and some are believed to have feigned conversion to Christianity for the sake of acceptance by the old Christian aristocratic families. One such family, the Wara Seh (more commonly called the "Yejju dynasty") converted to Christianity and eventually wielded power for over a century, ruling with the sanction of the Solomonic emperors. The last such Muslim noble to join the ranks of Ethiopian society was Mikael of Wollo who converted, was made Negus of Wollo, and later King of Zion, and even married into the Imperial family. He lived to see his son, Lij Iyasu, inherit the throne in 1913—only to be deposed in 1916 because of his conversion to Islam.

Madagascar

The nobility in Madagascar are known as the Andriana. In much of Madagascar, before French colonization of the island, the Malagasy people were organised into a rigid social caste system, within which the Andriana exercised both spiritual and political leadership. The word "Andriana" has been used to denote nobility in various ethnicities in Madagascar: including the Merina, the Betsileo, the Betsimisaraka, the Tsimihety, the Bezanozano, the Antambahoaka and the Antemoro.

The word Andriana has often formed part of the names of Malagasy kings, princes and nobles. Linguistic evidence suggests that the origin of the title Andriana is traceable back to an ancient Javanese title of nobility. Before the colonization by France in the 1890s, the Andriana held various privileges, including land ownership, preferment for senior government posts, free labor from members of lower classes, the right to have their tombs constructed within town limits, etc. The Andriana rarely married outside their caste: a high-ranking woman who married a lower-ranking man took on her husband's lower rank, but a high-ranking man marrying a woman of lower rank did not forfeit his status, although his children could not inherit his rank or property (cf. morganatic marriage).

In 2011, the Council of Kings and Princes of Madagascar endorsed the revival of a Christian Andriana monarchy that would blend modernity and tradition.

Nigeria

Contemporary Nigeria has a class of traditional notables which is led by its reigning monarchs, the Nigerian traditional rulers. Though their functions are largely ceremonial, the titles of the country's noblemen and women are often centuries old and are usually vested in the membership of historically prominent families in the various subnational kingdoms of the country.

Membership of initiatory societies that have inalienable functions within the kingdoms is also a common feature of Nigerian nobility, particularly among the southern tribes, where such figures as the Ogboni of the Yoruba, the Nze na Ozo of the Igbo and the Ekpe of the Efik are some of the most famous examples. Although many of their traditional functions have become dormant due to the advent of modern governance, their members retain precedence of a traditional nature and are especially prominent during festivals.

Outside of this, many of the traditional nobles of Nigeria continue to serve as privy counsellors and viceroys in the service of their traditional sovereigns in a symbolic continuation of the way that their titled ancestors and predecessors did during the pre-colonial and colonial periods. Many of them are also members of the country's political elite due to their not being covered by the prohibition from involvement in politics that governs the activities of the traditional rulers.

Holding a chieftaincy title, either of the traditional variety (which involves taking part in ritual re-enactments of your title's history during annual festivals, roughly akin to a British peerage) or the honorary variety (which does not involve the said re-enactments, roughly akin to a knighthood), grants an individual the right to use the word "chief" as a pre-nominal honorific while in Nigeria.

Asia

India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Nepal

In the Indian subcontinent during the British Raj, many members of the nobility were elevated to royalty as they became the monarchs of their princely states and vice versa as many princely state rulers were reduced from royals to noble zamindars. Hence, many nobles in the subcontinent had royal titles of Raja, Rai, Rana, Rao, etc. In Nepal, Kaji (Nepali: काजी) was a title and position used by nobility of Gorkha Kingdom (1559–1768) and Kingdom of Nepal (1768–1846). Historian Mahesh Chandra Regmi suggests that Kaji is derived from Sanskrit word Karyi which meant functionary.[22]

Other noble and aristocratic titles were Thakur, Sardar, Jagirdar, Mankari, Dewan, Pradhan, Kaji etc.

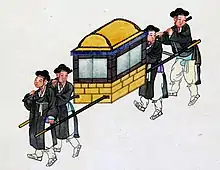

China

In East Asia the system was often modelled on imperial China, the leading culture. Emperors conferred titles of nobility. Imperial descendants formed the highest class of ancient Chinese nobility, their status based upon the rank of the empress or concubine from which they descend maternally (as emperors were polygamous). Numerous titles such as Taizi (crown prince), and equivalents of "prince" were accorded, and due to complexities in dynastic rules, rules were introduced for Imperial descendants. The titles of the junior princes were gradually lowered in rank by each generation while the senior heir continued to inherit their father's titles.

It was a custom in China for the new dynasty to ennoble and enfeoff a member of the dynasty which they overthrew with a title of nobility and a fief of land so that they could offer sacrifices to their ancestors, in addition to members of other preceding dynasties.

China had a feudal system in the Shang and Zhou dynasties, which gradually gave way to a more bureaucratic one beginning in the Qin dynasty (221 BC). This continued through the Song dynasty, and by its peak power shifted from nobility to bureaucrats.

This development was gradual and generally only completed in full by the Song dynasty. In the Han dynasty, for example, even though noble titles were no longer given to those other than the Emperor's relatives, the fact that the process of selecting officials was mostly based on a vouching system by current officials as officials usually vouched for their own sons or those of other officials meant that a de facto aristocracy continued to exist. This process was further deepened during the Three Kingdoms period with the introduction of the Nine-rank system.

By the Sui dynasty, however, the institution of the Imperial examination system marked the transformation of a power shift towards a full bureaucracy, though the process would not be truly completed until the Song dynasty.

Titles of nobility became symbolic along with a stipend while governance of the country shifted to scholar officials.

In the Qing dynasty titles of nobility were still granted by the emperor, but served merely as honorifics based on a loose system of favours to the Qing emperor.

Under a centralized system, the empire's governance was the responsibility of the Confucian-educated scholar-officials and the local gentry, while the literati were accorded gentry status. For male citizens, advancement in status was possible via garnering the top three positions in imperial examinations.

The Qing appointed the Ming imperial descendants to the title of Marquis of Extended Grace.

The oldest held continuous noble title in Chinese history was that held by the descendants of Confucius, as Duke Yansheng, which was renamed as the Sacrificial Official to Confucius in 1935 by the Republic of China. The title is held by Kung Tsui-chang. There is also a "Sacrificial Official to Mencius" for a descendant of Mencius, a "Sacrificial Official to Zengzi" for a descendant of Zengzi, and a "Sacrificial Official to Yan Hui" for a descendant of Yan Hui.

The bestowal of titles was abolished upon the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, as part of a larger effort to remove feudal influences and practises from Chinese society.

Islamic world

In some Islamic countries, there are no definite noble titles (titles of hereditary rulers being distinct from those of hereditary intermediaries between monarchs and commoners). Persons who can trace legitimate descent from Muhammad or the clans of Quraysh, as can members of several present or formerly reigning dynasties, are widely regarded as belonging to the ancient, hereditary Islamic nobility. In some Islamic countries they inherit (through mother or father) hereditary titles, although without any other associated privilege, e.g., variations of the title Sayyid and Sharif. Regarded as more religious than the general population, many people turn to them for clarification or guidance in religious matters.

In Iran, historical titles of the nobility including Mirza, Khan, ed-Dowleh and Shahzada ("Son of a Shah), are now no longer recognised. An aristocratic family is now recognised by their family name, often derived from the post held by their ancestors, considering the fact that family names in Iran only appeared in the beginning of the 20th century. Sultans have been an integral part of Islamic history .

During the Ottoman Empire in the Imperial Court and the provinces there were many Ottoman titles and appellations forming a somewhat unusual and complex system in comparison with the other Islamic countries. The bestowal of noble and aristocratic titles was widespread across the empire even after its fall by independent monarchs. One of the most elaborate examples is that of the Egyptian aristocracy's largest clan, the Abaza family.

Japan

Medieval Japan developed a feudal system similar to the European system, where land was held in exchange for military service. The daimyō class, or hereditary landowning nobles, held great socio-political power. As in Europe, they commanded private armies made up of samurai, an elite warrior class; for long periods, these held the real power without a real central government, and often plunged the country into a state of civil war. The daimyō class can be compared to European peers, and the samurai to European knights, but important differences exist.

Feudal title and rank were abolished during the Meiji Restoration in 1868, and was replaced by the kazoku, a five-rank peerage system after the British example, which granted seats in the upper house of the Imperial Diet; this ended in 1947 following Japan's defeat in World War II.

Philippines

Like other Southeast Asian countries, many regions in the Philippines have indigenous nobility, partially influenced by Hindu, Chinese, and Islamic custom. Since ancient times, Datu was the common title of a chief or monarch of the many pre-colonial principalities and sovereign dominions throughout the isles; in some areas the term Apo was also used.[23] With the titles Sultan and Rajah, Datu (and its Malay cognate, Datok) are currently used in some parts of the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei. These titles are the rough equivalents of European titles, albeit dependent on the actual wealth and prestige of the bearer.

Europe

European nobility originated in the feudal/seignorial system that arose in Europe during the Middle Ages.[24] Originally, knights or nobles were mounted warriors who swore allegiance to their sovereign and promised to fight for him in exchange for an allocation of land (usually together with serfs living thereon). During the period known as the Military Revolution, nobles gradually lost their role in raising and commanding private armies, as many nations created cohesive national armies.

This was coupled with a loss of the socio-economic power of the nobility, owing to the economic changes of the Renaissance and the growing economic importance of the merchant classes, which increased still further during the Industrial Revolution. In countries where the nobility was the dominant class, the bourgeoisie gradually grew in power; a rich city merchant came to be more influential than a nobleman, and the latter sometimes sought inter-marriage with families of the former to maintain their noble lifestyles.[25]

However, in many countries at this time, the nobility retained substantial political importance and social influence: for instance, the United Kingdom's government was dominated by the (unusually small) nobility until the middle of the 19th century. Thereafter the powers of the nobility were progressively reduced by legislation. However, until 1999, all hereditary peers were entitled to sit and vote in the House of Lords. Since then, only 92 of them have this entitlement, of whom 90 are elected by the hereditary peers as a whole to represent the peerage.

The countries with the highest proportion of nobles were Castile (probably 10%), Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (15% of an 18th-century population of 800,000), Spain (722,000 in 1768 which was 7–8% of the entire population) and other countries with lower percentages, such as Russia in 1760 with 500,000–600,000 nobles (2–3% of the entire population), and pre-revolutionary France where there were no more than 300,000 prior to 1789, which was 1% of the population (although some scholars believe this figure is an overestimate). In 1718 Sweden had between 10,000 and 15,000 nobles, which was 0.5% of the population. In Germany it was 0.01%.[26]

In the Kingdom of Hungary nobles made up 5% of the population.[27] All the nobles in 18th-century Europe numbered perhaps 3–4 million out of a total of 170–190 million inhabitants.[28][29] By contrast, in 1707, when England and Scotland united into Great Britain, there were only 168 English peers, and 154 Scottish ones, though their immediate families were recognised as noble.[30]

Apart from the hierarchy of noble titles, in England rising through baron, viscount, earl, and marquess to duke, many countries had categories at the top or bottom of the nobility. The gentry, relatively small landowners with perhaps one or two villages, were mostly noble in most countries, for example the Polish landed gentry. At the top, Poland had a far smaller class of "magnates", who were hugely rich and politically powerful. In other countries the small groups of Spanish Grandee or Peer of France had great prestige but little additional power.

Latin America

In addition to the nobility of a variety of native populations in what is now Latin America (such as the Aymara, Aztecs, Maya, and Quechua) who had long traditions of being led by monarchs and nobles, peerage traditions dating to the colonial (and post-colonial imperial periods in the case of such countries as Mexico and Brazil), have left noble families in each of them that have ancestral ties to those nations' Indigenous and European families, especially the Spanish but also the Portuguese and French nobility.

Bolivia

From the many historical native chiefs and rulera of pre-Columbian Bolivia to the Criollo upper class that dates to the era of Colonial Bolivia and that has ancestral ties to the Spanish nobility, Bolivia has several groups that may fit into the category of nobility.

The country also has a ceremonial monarchy that is recognized as part of the Plurinational State of Bolivia and that is led by a titular ruler who is known as the Afro-Bolivian king. The members of the royal house that he belongs to are the direct descendants of an old African tribal monarchy that were brought to Bolivia as slaves. They have provided leadership to the Afro-Bolivian community ever since that event and have been officially recognized by Bolivia's government since 2007.[31]

Brazil

The nobility in Brazil began during the colonial era with the Portuguese nobility. When Brazil became a united kingdom with Portugal in 1815, the first Brazilian titles of nobility were granted by the King of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves.

With the independence of Brazil in 1822 as a constitutional monarchy, the titles of nobility initiated by the King of Portugal were continued and new titles of nobility were created by the Emperor of Brazil. However, according to the Brazilian Constitution of 1824, the Emperor conferred titles of nobility, which were personal and therefore non-hereditary, unlike the earlier Portuguese and Portuguese-Brazilian titles, being inherited exclusively to the royal titles of the Brazilian Imperial Family.

During the existence of the Empire of Brazil, 1,211 noble titles were acknowledged. With the proclamation of the First Brazilian Republic, in 1889, the Brazilian nobility was extinguished. It was also prohibited, under penalty of accusation of high treason and the suspension of political rights, to accept noble titles and foreign decorations without the proper permission of the State. In particular, the nobles of greater distinction, by respect and tradition, were allowed to use their titles during the republican regime. The Imperial Family also could not return to the Brazilian soil until 1921, when the Banishment Law was repealed.

Mexico

The Mexican nobility were a hereditary nobility of Mexico, with specific privileges and obligations determined in the various political systems that historically ruled over the Mexican territory.

The term is used in reference to various groups throughout the entirety of Mexican history, from formerly ruling indigenous families of the pre-Columbian states of present-day Mexico, to noble Mexican families of Spanish, mestizo, and other European descent, which include conquistadors and their descendants (ennobled by King Philip II in 1573), untitled noble families of Mexico, and holders of titles of nobility acquired during the Viceroyalty of the New Spain (1521–1821), the First Mexican Empire (1821–1823), and the Second Mexican Empire (1862–1867); as well as bearers of titles and other noble prerogatives granted by foreign powers who have settled in Mexico.

The Political Constitution of Mexico has prohibited the State from recognizing any titles of nobility since 1917. The present United Mexican States does not issue or recognize titles of nobility or any hereditary prerogatives and honors. Informally, however, a Mexican aristocracy remains a part of Mexican culture and its hierarchical society.

Nobility by nation

A list of noble titles for different European countries can be found at Royal and noble ranks.

Africa

- Botswanan chieftaincy

- Kgosi

- Burundian nobility

- Egyptian nobility

- Ethiopian nobility

- Ras

- Jantirar

- Ghanaian chieftaincy

- Akan chieftaincy

- Malagasy nobility

- Malian nobility

- Nigerian chieftaincy

- Nigerian traditional rulers

- Lamido

- Hakimi

- Oba

- Ogboni

- Eze

- Nze na Ozo

- Lamido

- Nigerian traditional rulers

- Rwandan nobility

- Somali nobility

- Zimbabwean chieftaincy

America

- Canadian peers and baronets

- Brazilian nobility

- Cuban nobility

- Kuraka (Peru)

- Mexican nobility

- Pipiltin

Asia

- Armenian nobility

- Chinese nobility

- Indian peers and baronets

- Kaji (Nepal)

- Pande family

- Basnyat family

- Thapa family

- Kunwar family or Rana dynasty

- Indonesian (Dutch East Indies) nobility

- Japanese nobility

- Kuge

- Daimyō

- Burmese nobility

- Burmese Mon nobility

- Korean nobility

- Vietnamese nobility

- Malay nobility

- Mongolian nobility

- Ottoman titles

- Principalía of the Philippines

- Thai nobility

Europe

- Albanian nobility

- Austrian nobility

- Baltic nobility – ethnically Baltic German nobility in the modern area of Estonia and Latvia

- Belgian nobility

- British nobility

- British peerage

- Peerage of Great Britain

- Peerage of the United Kingdom

- English peerage

- Scottish noblesse

- Scottish peerage

- Barons

- Lairds

- Welsh Peers

- Chiefs of the Name

- Irish peerage

- British peerage

- Byzantine aristocracy and bureaucracy

- Phanariotes

- Croatian nobility

- Czech nobility

- Danish nobility

- Dutch nobility

- Finnish nobility

- French nobility

- German nobility

- Freiherr

- Graf

- Junker

- Hungarian nobility

- Icelandic nobility

- Irish nobility

- Italian nobility

- Black Nobility

- Lithuanian nobility

- Montenegrin nobility

- Norwegian nobility

- Polish nobility

- Magnates

- Portuguese nobility

- Russian nobility

- Serbian nobility

- Spanish nobility

- Swedish nobility

- Swiss nobility

Oceania

- Australian peers and baronets

- Fijian nobility

- Polynesian nobility

- Samoan nobility

- Tongan nobles

See also

- Almanach de Gotha

- Aristocracy (class)

- Ascribed status

- Baig

- Caste (social hierarchy of India)

- Debutante

- False titles of nobility

- Gentleman

- Gentry

- Grand Burgher (German: Großbürger)

- Heraldry

- Honour

- Kaji (Nepal)

- King

- List of fictional nobility

- List of noble houses

- Magnate

- Military elite

- Military Revolution

- Nobiliary particle

- Noblesse oblige

- Nze na Ozo

- Ogboni

- Pasha

- Patrician (ancient Rome)

- Patrician (post-Roman Europe)

- Peerage

- Petty nobility

- Princely state

- Raja

- Redorer son blason

- Royal descent

- Social environment

- Symbolic capital

References

- "Move Over, Kate Middleton: These Commoners All Married Royals, Too". Vogue. Archived from the original on 2018-10-25. Retrieved 2018-10-24.

- Oliver, Revilo P. (1978). "Tacitean "Nobilitas"" (PDF). Illinois Classical Studies. University of Illinois Press. 3: 238–261. hdl:2142/11694. JSTOR 23062619. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018.

- Bengtsson, Erik; Missiaia, Anna; Olsson, Mats; Svensson, Patrick (12 June 2018). "The Wealth of the Richest: Inequality and the Nobility in Sweden, 1750–1900" (PDF). Taylor & Francis: 1–28. doi:10.1080/03468755.2018.1480538. S2CID 149906044. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 September 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2018 – via Lund University Libraries.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Lukowski, Jerzy (2003). Hall, Lesley; Lilley, Keith D.; MacMaster, Neil; Spellman, W. M.; Waite, Gary K.; Webb, Diana (eds.). The European Nobility in the Eighteenth Century (PDF). Palgrave Macmillan. p. 243. ISBN 0-333-74440-3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-09-15. Retrieved 2018-09-15 – via Zaccheus Onumba Dibiaezue Memorial Libraries.

- Country Life (magazine), Who really owns Britain? Archived 2021-11-04 at the Wayback Machine, 16. October 2010.

- "Half of England is owned by less than 1% of the population". The Guardian. 17 April 2019. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021. Retrieved 30 October 2021.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 728.

- Jonathan, Dewald (1996). The European nobility, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 117. ISBN 0-521-42528-X. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Pine, L.G. (1992). Titles: How the King became His Highness. New York: Barnes & Noble Books. pp. 77. ISBN 978-1-56619-085-5.

- "The consolidation of Noble Power in Europe, c. 1600–1800". Archived from the original on 2013-12-13. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- W. Doyle, Essays on Eighteenth Century France, London, 1995

- An opinion of Innes of Learney differentiates the system in use in Scotland from many other European traditions, in that armorial bearings which are entered in the Public Register of All Arms and Bearings in Scotland by warrant of the Lord Lyon King of Arms are legally "Ensigns of Nobility", and although the historical accuracy of that interpretation has been challenged Archived 2010-01-09 at the Wayback Machine, Innes of Learney's perspective is accepted in the Stair Memorial Encyclopaedia entry, 'Heraldry' (Volume 11), 3, The Law of Arms. 1613. The nature of arms.

- Larence, Sir James Henry (1827) [first published 1824]. The nobility of the British Gentry or the political ranks and dignities of the British Empire compared with those on the continent (2nd ed.). London: T.Hookham – Simpkin and Marshall. Archived from the original on 2013-05-26. Retrieved 2013-01-06.

- Ruling of the Court of the Lord Lyon (26/2/1948, Vol. IV, page 26): "With regard to the words 'untitled nobility' employed in certain recent birthbrieves in relation to the (Minor) Baronage of Scotland, Finds and Declares that the (Minor) Barons of Scotland are, and have been both in this nobiliary Court and in the Court of Session recognised as a ‘titled nobility’ and that the estait of the Baronage (i.e., Barones Minores) are of the ancient Feudal Nobility of Scotland". This title is not, however, a peerage, thus Scotland's noblesse ranks in England as gentry.

- Ölyvedi Vad Imre. (1930) Nemességi könyv. Koroknay-Nyomda. Szeged, Hungary. 45p.

- Ölyvedi Vad Imre. (1930) Nemességi könyv. Koroknay-Nyomda. Szeged, Hungary. 85.p

- "The annual register. v.51 1809". HathiTrust: 813. Archived from the original on 2021-09-25. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

The nobility of Valencia..are, by themselves, divided into three classes, blue blood, red blood, and yellow blood. Blue blood is confined to families who have been made grandees.

- "Helen, by Maria Edgeworth". www.gutenberg.org. Archived from the original on 2020-02-15. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

One in particular, from Spain, of high rank and birth, of the sangre azul, the blue blood, who have the privilege of the silken cord if they should come to be hanged.

- The politics of aristocratic empires by John Kautsky. January 1997. ISBN 9781412838351. Archived from the original on 2016-05-27. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Malte-Brun, Conrad; Balbi, Adriano (1842). System of universal geography, founded on the works of Malte-Burn and Balbi; embracing a historical sketch of the progress of geographical discovery, the principles of mathematical and physical geography, and a complete description from the most recent sources, of the political and social condition of the world ... Edinburgh; London: Adam and Charles Black; Longman, Brown, Green, & Longmans. p. 537. OCLC 33328020. Archived from the original on 2021-09-25. Retrieved 2020-09-15.

The Spanish community is divided into two great castes, those of pure Gothic or blue blood, and those of mixed Gothic and Moorish descent, or black blood.

- Robert Lacey, Aristocrats. Little, Brown and Company, 1983, p. 67

- Regmi 1979, p. 43.

- The Olongapo Story Archived 2020-02-19 at the Wayback Machine, July 28, 1953 – Bamboo Breeze – Vol.6, No.3

- Karl Ferdinand Werner, Naissance de la noblesse. L'essor des élites politiques en Europe. Fayard, Paris 1998, ISBN 2-213-02148-1.

- Marcassa, Stefania, Jérôme Pouyet, and Thomas Trégouët. "Marriage strategy among the European nobility." Explorations in Economic History 75 (2020): 101303. online Archived 2021-07-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Jorn Leonhard, and Christian Wieland, eds. What Makes the Nobility Noble?: Comparative Perspectives from the Sixteenth to the Twentieth Century (2011).

- Jonathan, Dewald (1996). The European nobility, 1400–1800. Cambridge University Press. p. 25. ISBN 0-521-42528-X. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2015-10-23.

- Jean, Meyer (1973). Noblesses et pouvoirs dans l'Europe d'Ancien Régime, Hachette Littérature. Hachette. ISBN 9782346228201. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- Jean-Pierre, Labatut (1981). Les noblesses européennes de la fin du XVe siècle à la fin du XVIIIe siècle. Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 9782130353447. Archived from the original on 2022-04-07. Retrieved 2020-11-02.

- Farnborough, T. E. May, 1st Baron (1896). Constitutional History of England since the Accession of George the Third, 11th ed. Volume I, Chapter 5, pp.273–281. Archived 2008-06-22 at the Wayback Machine London: Longmans, Green and Co.

- Rodríguez, Andres (19 January 2018). "El retorno del rey negro boliviano a sus raíces africanas – El País". El País. Archived from the original on 2020-11-09. Retrieved 2020-03-07.

External links

family (P53) (see uses)

family (P53) (see uses)

- WW-Person, an on-line database of European noble genealogy

- Worldroots, a selection of art and genealogy of European nobility

- Worldwidewords

- Etymology OnLine

- Genesis of European Nobility Archived 2012-01-10 at the Wayback Machine

- A few notes about grants of titles of nobility by modern Serbian Monarchs