Voting at the Eurovision Song Contest

The winner of the Eurovision Song Contest is selected by a positional voting system. The most recent system was implemented in the 2016 contest, and sees each participating country award two sets of 12, 10, 8–1 points to their ten favourite songs: one set from their professional jury and the other from tele-voting.[1]

Overview

Small, demographically-balanced juries made up of ordinary people had been used to rank the entries, but after the widespread use of telephone voting in 1998 the contest organizers resorted to juries only in the event of a televoting malfunctions. In 2003, Eircom's telephone polling system malfunctioned. Irish broadcaster RTÉ did not receive the polling results from Eircom in time, and substituted votes by a panel of judges.[2] Between 1997 and 2003 (the first years of televoting), lines were opened to the public for only five minutes after the performance and recap of the final song. Between 2004 and 2006 the lines were opened for ten minutes, and from 2007 to 2009 they were opened for fifteen minutes. In 2010 viewers were allowed to vote during the performances, but this was rescinded for the 2012 contest. Since the 2004 contest, the presenters will start the televoting process with the phrase "Europe, start voting now!". This invitation also applies to Australia from 2015 to 2023 ("Europe and Australia, start voting now!"). At the end of the voting period, the presenters will invite viewers and the audience to stop with the ten second final countdown along with the phrase "Europe, stop voting now!".[3] The UK is not able to vote via SMS or the smartphone app due to legislation implemented after the 2007 British premium-rate phone-in scandal.

The BBC contacted regional juries by telephone to choose the 1956 winners, and the European Broadcasting Union (producers of the contest) later began contacting international juries by telephone. This method continued to be used until 1993. The following year saw the first satellite link-up to juries.[4]

To announce the votes, the contest's presenters connect by satellite to each country in turn and inviting a spokesperson to read the country's votes in French or English. The presenters originally repeated the votes in both languages, but since 2004 the votes have been translated due to time constraints. To offset increased voting time required by a larger number of participating countries, since 2006 only countries' 8-, 10-, and 12-point scores were read aloud; one- to seven-point votes were added automatically to the scoreboard while each country's spokesperson was introduced. The scoreboard displays the number of points each country has received and, since 2008, a progress bar indicating the number of countries which have voted. Since 2016, only the 12-point score is read aloud due to the new voting system, meaning that the nine scoring countries were added automatically to the scoreboard (1-8 and 10 points). In addition, the televoting points are combined and the presenters announce them in order, starting from the country with the lowest score and ending with the country with the highest score from the televoting. Beginning with the 2019 contest, the televoting points are announced by the presenters based on the juries' rankings in reverse order.

Voting systems

| Year | Points | Voting system |

|---|---|---|

| 1956 | Unknown | The system of voting for the 1956 contest has never been revealed. |

| 1957–1961 | 10–1 | Ten-member juries distributed 10 points among their favourite songs. |

| 1962 | 3–1 | Ten-member juries awarded points to their three favourite songs. |

| 1963 | 5–1 | Twenty-member juries awarded points to their five favourite songs. |

| 1964–1966 | 5, 3, 1 / 6, 3 / 9 | Ten-member juries distributed 9 points in three possible ways. If all their votes went to one single song, it got all the 9 points, if they went to two songs, they got 6 and 3 points, and if they went to three or more, the top three got 5, 3 and 1 points. No jury ever gave 9 points to a single song, but Belgium used the 6-3 system in 1965. |

| 1967–1969 | 10–1 | Ten-member juries distributed 10 points among their favourite songs. |

| 1970 | Ten-member juries distributed 10 points among their favourite songs. A tie-breaking round was available. | |

| 1971–1973 | 10–2 | Two-member juries (one aged over 25 and the other under 25, with at least 10 years between their ages) rated songs between 1 and 5 points. |

| 1974 | 10–1 | Ten-member juries distributed 10 points among their favourite songs. |

| 1975–1996 | 12, 10, 8–1 | All countries had at least eleven jury members (later rising to sixteen) that would award points to their top ten songs. From 1975 to 1979, the scores were announced in the order in which the songs performed, while the ascending format of going from 1-8 points, 10 points and finally 12 points, was introduced in 1980. |

| 1997 | Twenty countries had jury members and five countries used televote to decide which songs would get points.[5] | |

| 1998–2000 | All countries should use telephone voting to decide which songs would receive points. In exceptional circumstances (e.g. weak telephone system) where televoting was not possible at all, a jury was used.[6][7][8] | |

| 2001–2002 | Every broadcaster was free to make a choice between the full televoting system and the mixed 50/50 system to decide which songs would receive points. In exceptional circumstances where televoting was not possible, only a jury was used.[9][10] | |

| 2003 | All countries should use telephone/SMS voting to decide which songs would receive points. In exceptional circumstances where televoting was not possible at all, only a jury was used.[11] | |

| 2004–2008; 2009 (semi-finals) | All countries used televoting and/or SMS-voting to decide which songs would receive points. Back-up juries are used by each country (with eight members) in the event of a televoting failure. | |

| 2009 (final); 2010–2012 | All countries used televoting and/or SMS-voting (50%) and five-member juries (50%), apart from San Marino which was 100% jury due to country size. This is so called jury–televote 50/50. In the event of a televoting failure, only a jury is used by that country; in the event of a jury failure, only televoting is used by that country. The two parts of the vote were combined by awarding 12, 10, 8–1 points to the top ten in each discipline, then combining the scores. Where two songs were tied, the televote score took precedence. | |

| 2013–2015 | The same as in 2009–12, except jury and televote are combined differently. The jurors and televoting each rank all the competing entries, rather than just their top ten. The scores are then added together and in the event of a tie, the televote score takes precedence.[12][13] | |

| 2016–2017 | (12, 10, 8–1) × 2 | The jury and the televote each award an independent set of points. First the jury points are announced and then the televoting points are calculated together before being added to the jury points, effectively doubling the points which can be awarded in total.[1] |

| 2018–present | The same as in 2016–17, but the points from a country's jury are now calculated using an exponential weight model that gives more weight to higher-ranked songs and lessens the impact of one juror placing a song much lower in their rankings.[14] |

The most-used voting system (other than the current one) was last used for the 1974 contest. This system was used from 1957 to 1961 and from 1967 to 1969. Ten jurors in each country each cast one vote for their favourite song. In 1969 this resulted in a four-way tie for first place (between the UK, the Netherlands, France, and Spain), with no tie-breaking procedure. A second round of voting in the event of a tie was introduced to this system the following year.

From 1962 to 1966, a voting system similar to the current one was used. In 1962, each country awarded its top three 1, 2 and 3 points; in 1963 the top five were awarded 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 points, and from 1964 to 1966, each country usually awarded its top three 1, 3 and 5 points. With the latter system, a country could choose to give points to two countries instead of three (giving 3 to one and 6 to the other); in 1965, Belgium awarded the United Kingdom 6 points and Italy 3. Although it was possible to give one country 9 points, this never occurred.

The 1971, 1972, and 1973 contests saw the jurors "in vision" for the first time. Each country was represented by two jurors: one older than 25 and one younger, with at least 10 years' difference in their ages. Each juror gave a minimum of 1 point and a maximum of 5 points to each song. In 1974 the previous system of ten jurors was used, and the following year the current system was introduced. Spokespeople were next seen on screen in 1994 with a satellite link to the venue.

The 2004 contest had its first semifinal, with a slight change in voting: countries which did not qualify from the semifinal would be allowed to cast votes in the final. This resulted in Ukraine's Ruslana finishing first, with a record 280 points. If the voting had been conducted as it had been from 1956 to 2003 (when only finalist countries could vote), Serbia and Montenegro's Željko Joksimović would have won the contest with 190 points: a 15-point lead over Ruslana, who would have scored 175 points. To date, non-qualifying countries are still allowed to vote in the final. In 2006, Serbia and Montenegro were able to vote in the semi-final and the final despite their non-participation due to a scandal in the selection process (which resulted in Macedonia entering the final instead of Poland).

With the introduction of two semifinals in 2008, a new method of selecting finalists was created. The top nine songs (ranked by televote) qualified, along with one song selected by the back-up juries. This method, in most cases, meant that the tenth song in the televoting failed to qualify; this attracted some criticism, especially from Macedonia (who had placed 10th in the televote in both years).[15] In 2010 the 2009 final system was used, with a combination of televoting and jury votes from each country also used to select the semi-finalists.[16] Each participating country had a national jury, consisting of five music-industry professionals[17] appointed by national broadcasters.[18]

Highest scores

The Russian entry at the 2015 contest, "A Million Voices" by Polina Gagarina, became the first song to get over 300 points without winning the contest (and the only one during the era when each country delivered only one set of points); with a new voting system introduced in 2016, Australia became the first country to get over 500 points without winning the contest. In 2017, Bulgaria became the first non-winning country to score above 600 points, as well as Portugal becoming the first country to get over 750 points – winning the contest as a result of this with the song "Amar pelos dois" by Salvador Sobral. As the number of voting countries and the voting systems have varied, it may be more relevant to compare what percentage of all points awarded in the competition that each song received (computed from the published scoreboards).[19]

Since the introduction of the new voting system in 2016, the Swedish entry at the 2022 contest, "Hold Me Closer" by Cornelia Jakobs, currently holds the record for receiving the highest percentage of maximum points from the juries, receiving 222 out of 240 points (92.50%) in the second semi-final. "Stefania" by Kalush Orchestra, winner of that year's contest for Ukraine, currently holds the record for receiving the highest percentage of maximum points from the televoting, receiving 439 out of 468 points (93.80%) in the final.[20]

Top five winners by percentage of all votes

This table shows top five winning songs by the percentage from the all votes cast.

| Year | Country | Artist | Song | Points | Percentage of all points cast | Percentage of maximum possible points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1964 | Gigliola Cinquetti | "Non ho l'età" | 49 | 34.03% | 65.33% | |

| 1957 | Corry Brokken | "Net als toen" | 31 | 31.00% | 34.44% | |

| 1967 | Sandie Shaw | "Puppet on a String" | 47 | 27.65% | 29.38% | |

| 1962 | Isabelle Aubret | "Un premier amour" | 26 | 27.08% | 57.78% | |

| 1958 | André Claveau | "Dors, mon amour" | 27 | 27.00% | 30.00% |

Top five winners by percentage of the maximum possible score

This table shows top five winning songs by the percentage from the maximum possible score a song can achieve.

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song | Points | Percentage of all points cast | Percentage of maximum possible points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | Anne-Marie David | "Tu te reconnaîtras" | 129 | 14.05% | 80.63% | |

| 1976 | Brotherhood of Man | "Save Your Kisses for Me" | 164 | 15.71% | 80.39% | |

| 1982 | Nicole | "Ein bißchen Frieden" | 161 | 15.42% | 78.92% | |

| 1997 | Katrina and the Waves | "Love Shine a Light" | 227 | 15.66% | 78.82% | |

| 2009 | Alexander Rybak | "Fairytale" | 387 | 15.89% | 78.66% |

Top ten participants by number of points

This table shows top ten participating songs (both winning and non-winning) by the number of points received.

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song | Points | Percentage of all points cast | Percentage of maximum possible points |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Salvador Sobral | "Amar pelos dois" | 758 | 15.56% | 77.03% | |

| 2022 | Kalush Orchestra | "Stefania" | 631 | 13.6% | 67.41% | |

| 2017 | Kristian Kostov | "Beautiful Mess" | 615 | 12.62% | 62.50% | |

| 2016 | Jamala | "1944" | 534 | 10.96% | 54.27% | |

| 2018 | Netta | "Toy" | 529 | 10.61% | 52.48% | |

| 2021 | Måneskin | "Zitti e buoni" | 524 | 11.58% | 57.46% | |

| 2016 | Dami Im | "Sound of Silence" | 511 | 10.48% | 51.93% | |

| 2021 | Barbara Pravi | "Voilà" | 499 | 11.03% | 54.71% | |

| 2019 | Duncan Laurence | "Arcade" | 498 | 10.60% | 51.25% | |

| 2016 | Sergey Lazarev | "You Are the Only One" | 491 | 10.32% | 49.89% |

Under the 2013–15 voting system Portugal would have received 17.12% of points in the 2017 competition.[21]

Top ten participants by number of jury points

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song | Jury points | Total points | Percentage of points from jury voting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Salvador Sobral | "Amar pelos dois" | 382 | 758 | 50.4% | |

| 2016 | Dami Im | "Sound of Silence" | 320 | 511 | 62.62% | |

| 2022 | Sam Ryder | "Space Man" | 283 | 466 | 60.72% | |

| 2017 | Kristian Kostov | "Beautiful Mess" | 278 | 615 | 45.2% | |

| 2018 | Cesár Sampson | "Nobody But You" | 271 | 342 | 79.24% | |

| 2021 | Gjon's Tears | "Tout l'Univers" | 267 | 432 | 61.8% | |

| 2022 | Cornelia Jakobs | "Hold Me Closer" | 258 | 438 | 58.90% | |

| 2018 | Benjamin Ingrosso | "Dance You Off" | 253 | 274 | 92.34% | |

| 2021 | Barbara Pravi | "Voilà" | 248 | 499 | 49.7% | |

| 2019 | Tamara Todevska | "Proud" | 247 | 305 | 80.98% |

Top ten participants by number of televoting points

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song | Televote points | Total points | Percentage of points from televoting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2022 | Kalush Orchestra | "Stefania" | 439 | 631 | 69.57% | |

| 2017 | Salvador Sobral | "Amar pelos dois" | 376 | 758 | 49.6% | |

| 2016 | Sergey Lazarev | "You Are the Only One" | 361 | 491 | 73.52% | |

| 2017 | Kristian Kostov | "Beautiful Mess" | 337 | 615 | 54.8% | |

| 2016 | Jamala | "1944" | 323 | 534 | 60.49% | |

| 2021 | Måneskin | "Zitti e buoni" | 318 | 524 | 60.69% | |

| 2018 | Netta | "Toy" | 317 | 529 | 59.92% | |

| 2019 | Keiino | "Spirit in the Sky" | 291 | 331 | 87.92% | |

| 2021 | Go_A | "Shum" | 267 | 364 | 73.35% | |

| 2017 | SunStroke Project | "Hey Mamma" | 264 | 374 | 70.59% |

Tie-breakers

A tie-break procedure was implemented after the 1969 contest, in which France, the Netherlands, Spain and the United Kingdom tied for first place. With no tie-breaking system in place at the time, all four countries were declared joint winners; in protest, Austria, Finland, Sweden, Norway and Portugal did not participate the following year.

In 1991, the tie-break procedure was implemented when Sweden and France both had 146 points at the end of the voting. At the time, there was no televoting system, and the tie-break rule was slightly different; the first tie-break rule at the time concerned the number of 12 points each country had received.[22][23] Both Sweden and France had received the maximum 12 points four times; when the number of 10-point scores was counted, Sweden, represented by Carola with "Fångad av en stormvind", claimed its third victory since it received five 10-point scores against France's two. The French entry, "Le Dernier qui a parlé..." performed by Amina, finished second with the smallest-ever losing margin.

The current tie-break procedure was implemented in the 2016 contest. In the procedure, sometimes known as a countback, if two (or more) countries tie, the song receiving more points from the televote is the winner. If the songs received the same number of televote points, the song that received at least one televote point from the greatest number of countries is the winner. If there is still a tie, a second tie-breaker counts the number of countries who assigned twelve televote points to each entry in the tie. Tie-breaks continue with ten points, eight points, and so on until the tie is resolved. If the tie cannot be resolved after the number of countries which assigned one point to the song is equal, the song performed earlier in the running order is declared the winner. The tie-break procedure originally applied only to first place ties or to determine a semi-final qualifier,[24] but since 2008 has been applied to all places.[25]

| Year | Use | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1956–1969 | — | No tie-breaking rules were in place. |

| 1970–1988 | Only to determine the winner. | The jury decided the winner through a simple vote for their favourite. |

| 1989–2003 | The winner of a tie is the country that received more 12 points, then 10 points, all the way down to 1. If the tie cannot be broken in this way, all tied countries are winners. | |

| 2004–2006 | To determine the winner and the 10th qualifier from the semi-final. | |

| 2007 | The winner of a tie is the country that received points from more countries, then the country that received more 12 points, then 10 points, all the way down to 1. If the tie cannot be broken in this way, the country that performed earlier wins the tie.[26][27] | |

| 2008–2015 | Used for all ties. | |

| 2016–present | The winner of a tie is the country that received more points from the televoting, then the country that received points from more countries in the televoting, then the country that received more 12 points in the televoting, then 10 points, all the way down to 1. If the tie cannot be broken in this way, the country that performed earlier wins the tie. |

Scoring no points

As each participating country casts a series of preference votes, under the current scoring system it is rare that a song fails to receive any points at all; such a result means that the song failed to make the top ten most popular songs in any country.

The first zero points in Eurovision were scored in 1962, under a new voting system. When a country finishes with a score of zero, it is often referred to in English-language media as nul points /ˌnjuːl ˈpwæ̃/[28] or nil points /ˌnɪl ˈpɔɪnts/, albeit incorrectly. Grammatical French for "no points" is pas de points, zéro points or aucun point, but none of these phrases are used in the contest; before the voting overhaul in 2016, no-point scores were not announced by the presenters. Following the change in the voting system, a country receiving no points from the public televote is simply announced as receiving "zero points".[29]

Before 2016

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1962 | Fud Leclerc | "Ton nom" | |

| Víctor Balaguer | "Llámame" | ||

| Eleonore Schwarz | "Nur in der Wiener Luft" | ||

| De Spelbrekers | "Katinka" | ||

| 1963 | Annie Palmen | "Een speeldoos" | |

| Anita Thallaug | "Solhverv" | ||

| Laila Halme | "Muistojeni laulu" | ||

| Monica Zetterlund | "En gång i Stockholm" | ||

| 1964 | Nora Nova | "Man gewöhnt sich so schnell an das Schöne" | |

| António Calvário | "Oração" | ||

| Sabahudin Kurt | "Život je sklopio krug" | ||

| Anita Traversi | "I miei pensieri" | ||

| 1965 | Conchita Bautista | "¡Qué bueno, qué bueno!" | |

| Ulla Wiesner | "Paradies, wo bist du?" | ||

| Lize Marke | "Als het weer lente is" | ||

| Viktor Klimenko | "Aurinko laskee länteen" | ||

| 1966 | Tereza Kesovija | "Bien plus fort" | |

| Domenico Modugno | "Dio, come ti amo" | ||

| 1967 | Géraldine | "Quel cœur vas-tu briser?" | |

| 1970 | David Alexandre Winter | "Je suis tombé du ciel" | |

| 1978 | Jahn Teigen | "Mil etter mil" | |

| 1981 | Finn Kalvik | "Aldri i livet" | |

| 1982 | Kojo | "Nuku pommiin" | |

| 1983 | Remedios Amaya | "¿Quién maneja mi barca?" | |

| Çetin Alp and The Short Waves | "Opera" | ||

| 1987 | Seyyal Taner and Grup Locomotif | "Şarkım Sevgi Üstüne" | |

| 1988 | Wilfried | "Lisa Mona Lisa" | |

| 1989 | Daníel Ágúst | "Það sem enginn sér" | |

| 1991 | Thomas Forstner | "Venedig im Regen" | |

| 1994 | Ovidijus Vyšniauskas | "Lopšinė mylimai" | |

| 1997 | Tor Endresen | "San Francisco" | |

| Célia Lawson | "Antes do adeus" | ||

| 1998 | Gunvor | "Lass ihn" | |

| 2003 | Jemini | "Cry Baby"[30] | |

| 2015 | The Makemakes | "I Am Yours" | |

| Ann Sophie | "Black Smoke" |

The first time a host nation ever finished with nul points was in the 2015 final, when Austria's "I Am Yours" by The Makemakes scored zero. In 2003, following the UK's first zero score,[30] an online poll was held by OGAE UK to gauge public opinion about each zero-point entry's worthiness of the score. Spain's "¿Quién maneja mi barca?" (1983) won the poll as the song that least deserved a zero, and Austria's "Lisa Mona Lisa" (1988) was the song most deserving of a zero.[31]

In 2012, although it scored in the combined voting, France's "Echo (You and I)" by Anggun would have received no points if televoting alone had been used. In that year's first semi-final, although Belgium's "Would You?" by Iris received two points in the televoting-only hypothetical results from the Albanian jury (since Albania did not use televoting); Belgium would have received no official points from televoting alone.[32] In his book, Nul Points, comic writer Tim Moore interviews several of these performers about how their Eurovision score affected their careers.[33]

Since the creation of a single semi-final in 2004[34] and expansion to two semi-finals in 2008,[35] more than thirty countries vote each night – even countries which have been eliminated or have already qualified. No points are rarer; it requires a song to place less than tenth in every country in jury voting and televote.

Semi-finals

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | Piero and the MusicStars | "Celebrate" | |

| 2009 | Gypsy.cz | "Aven Romale" |

2016 onwards

With the new voting system being introduced in the 2016 contest, scoring no points in either the jury vote or televote is possible. An overall "nul points" has been scored only once.

In finals

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | James Newman | "Embers" |

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Manel Navarro | "Do It for Your Lover" | |

| 2019 | Kobi Marimi | "Home" | |

| 2021 | James Newman | "Embers" | |

| 2022 | Malik Harris | "Rockstars" |

Due to an error in relation to the jury votes from Belarus, Israel appeared to receive 12 points (all from Belarus) during the broadcast of the 2019 final. This was corrected by the EBU shortly afterwards.[36]

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | Gabriela Gunčíková | "I Stand" | |

| 2017 | Nathan Trent | "Running on Air" | |

| 2019 | S!sters | "Sister" | |

| 2021 | James Newman | "Embers" | |

| Blas Cantó | "Voy a quedarme" | ||

| Jendrik | "I Don't Feel Hate" | ||

| Jeangu Macrooy | "Birth of a New Age" | ||

| 2022 | Marius Bear | "Boys Do Cry" |

In semi-finals

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Valentina Monetta and Jimmie Wilson | "Spirit of the Night" |

| Contest | Country | Artist | Song |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | Claudia Faniello | "Breathlessly" | |

| 2018 | Ari Ólafsson | "Our Choice" | |

| 2019 | Paenda | "Limits" | |

| 2021 | Benny Cristo | "Omaga" | |

| 2022 | Nadir Rustamli | "Fade to Black" | |

Junior Eurovision

No entry in the Junior Eurovision Song Contest has ever received nul points; between 2005 and 2015, each contestant began with 12 points to prevent such a result.[37] However, there has not been a situation that the 12 points received in the beginning would have remained as the sole points. The closest to that was Croatia in 2014 which ended up with 13 points after receiving a single point from San Marino. On 15 October 2012, it was announced by the EBU, that for the first time in the contest's history a new "Kids Jury" was being introduced into the voting system. The jury consists of members aged between 10 and 15, and representing each of the participating countries. A spokesperson from the jury would then announce the points 1–8, 10 and the maximum 12 as decided upon by the jury members.[38] In 2016 the Kids Jury was removed and instead, each country awarded 1–8, 10 and 12 points from both adult and kid's juries, also eliminating televoting from the contest.[39] An expert panel were also present at the 2016 contest, with each of the panelists being able to award 1–8, 10 and 12 points themselves.[40]

In 2018, Portugal and Wales received no points in the jury voting.[41] In 2019, Portugal once again received no points in the jury voting.[42]

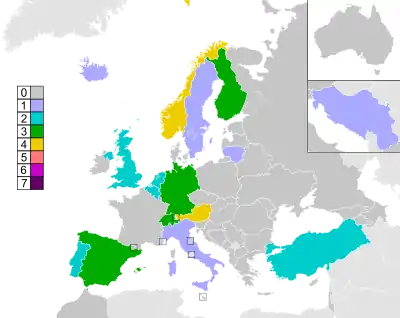

Regional bloc voting

Although statistical analysis of the results from 2001 to 2005 suggests regional bloc voting,[43] it is debatable how much in each case is due to ethnic diaspora voting, a sense of ethnic kinship, political alliances or a tendency for culturally-close countries to have similar musical tastes.[44] Several countries can be categorised as voting blocs, which regularly award one another high points.[43] The most common examples are Cyprus and Greece, Moldova and Romania, Belarus and Russia and the Nordic countries.

It is still common for countries to award points to their neighbours regularly, even if they are not part of a voting bloc (for example, Finland and Estonia or Germany and Denmark, Greece and Albania or Armenia and Russia). Votes may also be based on a diaspora: Greece, Turkey, Poland, Lithuania, Russia and the former Yugoslav countries normally get high scores from Germany or the United Kingdom, Armenia gets votes from France and Belgium, Poland from Ireland, Romania from Spain and Italy, and Albania from Switzerland, Italy and San Marino. Former Eurovision TV director Bjørn Erichsen disagreed with the assertion that regional bloc voting significantly affects the contest's outcome, saying that Russia's first victory in 2008 was only possible with votes from thirty-eight of the participating countries.[45]

In a 2017 study,[46] a new methodology is presented which allows a complete analysis of the competition from 1957 until 2017. The voting patterns change and the previous studies restrained their analysis to a particular time window where the voting scheme is homogeneous and this approach allows the sampling comparison over arbitrary periods consistent with the unbiased assumption of voting patterns. This methodology also allows for a sliding time window to accumulate a degree of collusion over the years producing a weighted network. The previous results are supported and the changes over time provide insight into the collusive behaviours given more or less choice.

See also

- Kids Jury in the Junior Eurovision Song Contest

References

- Jordan, Paul (18 February 2016). "Biggest change to Eurovision Song Contest voting since 1975". eurovision.tv. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Nick, Paton Walsh (2003-05-30). "Vote switch 'stole Tatu's Eurovision win'". The Guardian.

- "Eurovision 2014 Grand Final". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 24 May 2021.

- "Eurovision 1994 English commentary". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 4 October 2020.

- "Eurovision 1997". Eurovision.tv. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "Eurovision history". Eurovision.tv. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "Rules of Eurovision Song Contest 1999" (PDF). Myledbury. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "Rules of Eurovision Song Contest 2000" (PDF). Myledbury. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "Rules of Eurovision Song Contest 2001" (PDF). myledbury. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "Rules of Eurovision Song Contest 2002" (PDF). Myledbury. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "Rules of Eurovision Song Contest 2003" (PDF). myledbury. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-17. Retrieved 2015-11-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Eurovision 2013: How will 'Birds' fly for the Netherlands?". Sofabet.com. March 11, 2013.

- "Subtle but significant: EBU changes weight of individual jury rankings". eurovision.tv. April 27, 2018.

- Viniker, Barry (2009-05-20). "FYR Macedonia threatens Eurovision withdrawal". ESCToday. Archived from the original on 2009-05-21. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- Bakker, Sietse (2009-10-11). "Exclusive: Juries also get 50% stake in Semi-Final result!". EBU. Retrieved 2009-10-11.

- Bakker, Sietse (22 January 2015). "EBU restores televoting window as from 2012". European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-30. Retrieved 2015-05-15.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) read 2015-05-20 - "Eurovision 2021 Results: Voting & Points". Eurovisionworld. Retrieved 2021-06-17.

- "Eurovision 2022 Results: Voting & Points". Eurovisionworld. Retrieved 2022-05-15.

- "Rules of the Eurovision Song Contest 2002" (PDF). Myledbury.co.uk. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- "Rules of the Eurovision Song Contest 2003" (PDF). Myledbury.co.uk. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- "Public rules of the 60th Eurovision Song Contest" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 1 June 2015.

- "Eurovision 2008 Final". Eurovision.tv. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- "Main rules of Eurovision Song Contest (as of 2007 edition)". esckaz. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- "Main rules of Eurovision Song Contest (as of 2008 edition)". esckaz. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- "nul points". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 2021-08-16.

- Adrian Kavanagh (May 13, 2016). "2016 Eurovision Final results estimate (or televote estimate!): To Russia with Love or Going to a Land Down Under?". Retrieved January 15, 2019.

- "'Nul points' sparks Eurovision rejig". Broadcast. Retrieved 29 May 2003.

- "The BIG Zero". sechuk.com.

- Siim, Jarmo. "Eurovision 2012 split jury-televote results revealed". Eurovision. Retrieved 18 June 2012.

- Nul Points: Amazon.co.uk: Tim Moore: 9780099492979: Books. ASIN 0099492970.

- "Rules of the 2004 Eurovision Song Contest" (PDF). European Broadcasting Union. MyLedbury.

- "Eurovision: 2 semi finals confirmed!". Esctoday. Archived from the original on 25 June 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2007.

- "EBU Issues Statement on the 2019 Grand Final Result". eurovision.tv. 22 May 2019. Archived from the original on 24 May 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2019.

- "'Your votes please: the spokespersons'". ESC Today. 26 November 2005. Archived from the original on 1 June 2010. Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- Siim, Jarmo (15 October 2012). "Extra 'country' to give points in 2012". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Jordan, Paul (13 May 2016). "Format changes for the Junior Eurovision 2016". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Jordan, Paul (13 May 2016). "Jedward to appear at Junior Eurovision 2016!". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "Junior Eurovision Song Contest: Minsk 2018 - detailed voting results". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. 26 November 2018. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- "Junior Eurovision Song Contest: Gliwice-Silesia 2019 - detailed voting results". junioreurovision.tv. European Broadcasting Union. 25 November 2019. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Derek Gatherer (2005-09-20). "Comparison of Eurovision Song Contest Simulation with Actual Results Reveals Shifting Patterns of Collusive Voting Alliances". Retrieved 2007-05-14.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Victor Ginsburgh, Abdul Noury (October 2006). "The Eurovision Song Contest:: Is Voting Political or Cultural?" (PDF).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Bakker, Sietse. "Eurovision TV Director responds to allegations on voting". Retrieved 23 May 2010.

- Mantzaris, Alexander V., Rein, Samuel R. and Hopkins, Alexander D. "Examining Collusion and Voting Biases Between Countries During the Eurovision Song Contest Since 1957.", Journal of Artificial Societies and Social Simulation vol. 21, no. 1. 31 Jan 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2017.