Dividend

A dividend is a distribution of profits by a corporation to its shareholders.[1] When a corporation earns a profit or surplus, it is able to pay a proportion of the profit as a dividend to shareholders. Any amount not distributed is taken to be re-invested in the business (called retained earnings). The current year profit as well as the retained earnings of previous years are available for distribution; a corporation is usually prohibited from paying a dividend out of its capital. Distribution to shareholders may be in cash (usually a deposit into a bank account) or, if the corporation has a dividend reinvestment plan, the amount can be paid by the issue of further shares or by share repurchase. In some cases, the distribution may be of assets.

| Part of a series on |

| Accounting |

|---|

|

|

The dividend received by a shareholder is income of the shareholder and may be subject to income tax (see dividend tax). The tax treatment of this income varies considerably between jurisdictions. The corporation does not receive a tax deduction for the dividends it pays.[2]

A dividend is allocated as a fixed amount per share, with shareholders receiving a dividend in proportion to their shareholding. Dividends can provide stable income and raise morale among shareholders. For the joint-stock company, paying dividends is not an expense; rather, it is the division of after-tax profits among shareholders. Retained earnings (profits that have not been distributed as dividends) are shown in the shareholders' equity section on the company's balance sheet – the same as its issued share capital. Public companies usually pay dividends on a fixed schedule, but may declare a dividend at any time, sometimes called a special dividend to distinguish it from the fixed schedule dividends. Cooperatives, on the other hand, allocate dividends according to members' activity, so their dividends are often considered to be a pre-tax expense.

The word "dividend" comes from the Latin word dividendum ("thing to be divided").[3]

History

In financial history of the world, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) was the first recorded (public) company ever to pay regular dividends.[4][5] The VOC paid annual dividends worth around 18 percent of the value of the shares for almost 200 years of existence (1602–1800).[6]

Forms of payment

Cash dividends are the most common form of payment and are paid out in currency, usually via electronic funds transfer or a printed paper check. Such dividends are a form of investment income of the shareholder, usually treated as earned in the year they are paid (and not necessarily in the year a dividend was declared). For each share owned, a declared amount of money is distributed. Thus, if a person owns 100 shares and the cash dividend is 50 cents per share, the holder of the stock will be paid $50. Dividends paid are not classified as an expense, but rather a deduction of retained earnings. Dividends paid does not appear on an income statement, but does appear on the balance sheet.

Different classes of stocks have different priorities when it comes to dividend payments. Preferred stocks have priority claims on a company's income. A company must pay dividends on its preferred shares before distributing income to common share shareholders.

Stock or scrip dividends are those paid out in the form of additional shares of the issuing corporation, or another corporation (such as its subsidiary corporation). They are usually issued in proportion to shares owned (for example, for every 100 shares of stock owned, a 5% stock dividend will yield 5 extra shares).

Nothing tangible will be gained if the stock is split because the total number of shares increases, lowering the price of each share, without changing the market capitalization, or total value, of the shares held. (See also Stock dilution.)

Stock dividend distributions do not affect the market capitalization of a company.[7][8] Stock dividends are not includable in the gross income of the shareholder for US income tax purposes. Because the shares are issued for proceeds equal to the pre-existing market price of the shares; there is no negative dilution in the amount recoverable.[9][10]

Property dividends or dividends in specie (Latin for "in kind") are those paid out in the form of assets from the issuing corporation or another corporation, such as a subsidiary corporation. They are relatively rare and most frequently are securities of other companies owned by the issuer, however, they can take other forms, such as products and services.

Interim dividends are dividend payments made before a company's Annual General Meeting (AGM) and final financial statements. This declared dividend usually accompanies the company's interim financial statements.

Other dividends can be used in structured finance. Financial assets with known market value can be distributed as dividends; warrants are sometimes distributed in this way. For large companies with subsidiaries, dividends can take the form of shares in a subsidiary company. A common technique for "spinning off" a company from its parent is to distribute shares in the new company to the old company's shareholders. The new shares can then be traded independently.

Dividend coverage

Most often, the payout ratio is calculated based on dividends per share and earnings per share:[11]

A payout ratio greater than 100 means the company is paying out more in dividends for the year than it earned.

Dividends are paid in cash. On the other hand, earnings are an accountancy measure and do not represent the actual cash-flow of a company. Hence, a more liquidity-driven way to determine the dividend's safety is to replace earnings by free cash flow. The free cash flow represents the company's available cash based on its operating business after investments:

Dividend dates

A dividend that is declared must be approved by a company's board of directors before it is paid. For public companies in the US, four dates are relevant regarding dividends:[12]

Declaration date – the day the board of directors announces its intention to pay a dividend. On that day, a liability is created and the company records that liability on its books; it now owes the money to the shareholders.

In-dividend date – the last day, which is one trading day before the ex-dividend date, where shares are said to be cum dividend ('with [including] dividend'). That is, existing shareholders and anyone who buys the shares on this day will receive the dividend, and any shareholders who have sold the shares lose their right to the dividend. After this date the shares becomes ex dividend.

Ex-dividend date – the day on which shares bought and sold no longer come attached with the right to be paid the most recently declared dividend. In the United States and many European countries, it is typically one trading day before the record date. This is an important date for any company that has many shareholders, including those that trade on exchanges, to enable reconciliation of who is entitled to be paid the dividend. Existing shareholders will receive the dividend even if they sell the shares on or after that date, whereas anyone who bought the shares will not receive the dividend. It is relatively common for a share's price to decrease on the ex-dividend date by an amount roughly equal to the dividend being paid, which reflects the decrease in the company's assets resulting from the payment of the dividend.

Book closure date – when a company announces a dividend, it will also announce the date on which the company will temporarily close its books for share transfers, which is also usually the record date.

Record date – shareholders registered in the company's record as of the record date will be paid the dividend, while shareholders who are not registered as of this date will not receive the dividend. Registration in most countries is essentially automatic for shares purchased before the ex-dividend date.

Payment date – the day on which dividend cheques will actually be mailed to shareholders or the dividend amount credited to their bank account.

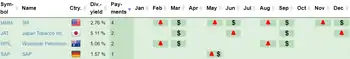

Dividend frequency

The dividend frequency describes the number of dividend payments within a single business year.[13] Most relevant dividend frequencies are yearly, semi-annually, quarterly and monthly. Some common dividend frequencies are quarterly in the US, semi-annually in Japan and Australia and annually in Germany.

Dividend-reinvestment

Some companies have dividend reinvestment plans, or DRIPs, not to be confused with scrips. DRIPs allow shareholders to use dividends to systematically buy small amounts of stock, usually with no commission and sometimes at a slight discount. In some cases, the shareholder might not need to pay taxes on these re-invested dividends, but in most cases they do.

Dividend taxation

Most countries impose a corporate tax on the profits made by a company.

Most jurisdictions also impose a tax on dividends paid by a company to its shareholders (stockholders). The tax treatment of a dividend income varies considerably between jurisdictions. The primary tax liability is that of the shareholder, though a tax obligation may also be imposed on the corporation in the form of a withholding tax. In some cases the withholding tax may be the extent of the tax liability in relation to the dividend. A dividend tax is in addition to any tax imposed directly on the corporation on its profits. Some jurisdictions do not tax dividends such as Singapore and UAE.[14]

A dividend paid by a company is not an expense of the company.

Australia and New Zealand

Australia and New Zealand have a dividend imputation system, wherein companies can attach franking credits or imputation credits to dividends. These franking credits represent the tax paid by the company upon its pre-tax profits. One dollar of company tax paid generates one franking credit. Companies can attach any proportion of franking up to a maximum amount that is calculated from the prevailing company tax rate: for each dollar of dividend paid, the maximum level of franking is the company tax rate divided by (1 − company tax rate). At the current 30% rate, this works out at 0.30 of a credit per 70 cents of dividend, or 42.857 cents per dollar of dividend. The shareholders who are able to use them, apply these credits against their income tax bills at a rate of a dollar per credit, thereby effectively eliminating the double taxation of company profits.

India

In India, a company declaring or distributing dividends is required to pay a Corporate Dividend Tax in addition to the tax levied on their income. The dividend received by the shareholders is then exempt in their hands. Dividend-paying firms in India fell from 24 percent in 2001 to almost 19 percent in 2009 before rising to 19 percent in 2010.[15] However, dividend income over and above ₹1,000,000 attracts 10 percent dividend tax in the hands of the shareholder with effect from April 2016.[16] Since the Budget 2020–2021, DDT has been abolished. Now, the Indian government taxes dividend income in the hands of investor according to income tax slab rates.[17]

United States and Canada

The United States and Canada impose a lower tax rate on dividend income than ordinary income, on the assertion that company profits had already been taxed as corporate tax.

Effect on stock price

After a stock goes ex-dividend (when a dividend has just been paid, so there is no anticipation of another imminent dividend payment), the stock price should drop.

To calculate the amount of the drop, the traditional method is to view the financial effects of the dividend from the perspective of the company. Since the company has paid say £x in dividends per share out of its cash account on the left hand side of the balance sheet, the equity account on the right side should decrease an equivalent amount. This means that a £x dividend should result in a £x drop in the share price.

A more accurate method of calculating this price is to look at the share price and dividend from the after-tax perspective of a share holder. The after-tax drop in the share price (or capital gain/loss) should be equivalent to the after-tax dividend. For example, if the tax of capital gains Tcg is 35%, and the tax on dividends Td is 15%, then a £1 dividend is equivalent to £0.85 of after-tax money. To get the same financial benefit from a capital loss, the after-tax capital loss value should equal £0.85. The pre-tax capital loss would be £0.85/1 − Tcg = £0.85/1 − 0.35 = £0.85/0.65 = £1.31. In this case, a dividend of £1 has led to a larger drop in the share price of £1.31, because the tax rate on capital losses is higher than the dividend tax rate.

Finally, security analysis that does not take dividends into account may mute the decline in share price, for example in the case of a price–earnings ratio target that does not back out cash; or amplify the decline when comparing different periods.

The effect of a dividend payment on share price is an important reason why it can sometimes be desirable to exercise an American option early.

Criticism and analysis

Some believe that company profits are best re-invested in the company with actions such as research and development, capital investment or expansion. Proponents of this view (and thus critics of dividends per se) suggest that an eagerness to return profits to shareholders may indicate the management having run out of good ideas for the future of the company. Some studies, however, have demonstrated that companies that pay dividends have higher earnings growth, suggesting that dividend payments may be evidence of confidence in earnings growth and sufficient profitability to fund future expansion.[18] Benjamin Graham and David Dodd wrote in Securities Analysis (1934): "The prime purpose of a business corporation is to pay dividends to its owners. A successful company is one that can pay dividends regularly and presumably increase the rate as time goes on."[19]

Other studies indicate that divided-paying stocks tend to offer superior long-term performance due to a variety of factors, such as dividends being associated with value stocks, with profitable companies exhibiting high levels of free cashflow and with mature, unfashionable companies that are overlooked by many investors and thus an effective contrarian strategy.[20][21][22][23][24]

Shareholders in companies that pay little or no cash dividends can reap the benefit of the company's profits when they sell their shareholding, or when a company is wound down and all assets liquidated and distributed amongst shareholders.

Tax implications

Taxation of dividends is often used as justification for retaining earnings, or for performing a stock buyback, in which the company buys back stock, thereby increasing the value of the stock left outstanding.

When dividends are paid, individual shareholders in many countries suffer from double taxation of those dividends:

- the company pays income tax to the government when it earns any income, and then

- when the dividend is paid, the individual shareholder pays income tax on the dividend payment.

In many countries, the tax rate on dividend income is lower than for other forms of income to compensate for tax paid at the corporate level.

A capital gain should not be confused with a dividend. Generally, a capital gain occurs where a capital asset is sold for an amount greater than the amount of its cost at the time the investment was purchased. A dividend is a parsing out a share of the profits, and is taxed at the dividend tax rate. If there is an increase of value of stock, and a shareholder chooses to sell the stock, the shareholder will pay a tax on capital gains (often taxed at a lower rate than ordinary income). If a holder of the stock chooses to not participate in the buyback, the price of the holder's shares could rise (as well as it could fall), but the tax on these gains is delayed until the sale of the shares.

Certain types of specialized investment companies (such as a REIT in the U.S.) allow the shareholder to partially or fully avoid double taxation of dividends.

Other corporate entities

Cooperatives

Cooperative businesses may retain their earnings, or distribute part or all of them as dividends to their members. They distribute their dividends in proportion to their members' activity, instead of the value of members' shareholding. Therefore, co-op dividends are often treated as pre-tax expenses. In other words, local tax or accounting rules may treat a dividend as a form of customer rebate or a staff bonus to be deducted from turnover before profit (tax profit or operating profit) is calculated.

Consumers' cooperatives allocate dividends according to their members' trade with the co-op. For example, a credit union will pay a dividend to represent interest on a saver's deposit. A retail co-op store chain may return a percentage of a member's purchases from the co-op, in the form of cash, store credit, or equity. This type of dividend is sometimes known as a patronage dividend or patronage refund, as well as being informally named divi or divvy.[25][26][27]

Producer cooperatives, such as worker cooperatives, allocate dividends according to their members' contribution, such as the hours they worked or their salary.[28]

Trusts

In real estate investment trusts and royalty trusts, the distributions paid often will be consistently greater than the company earnings. This can be sustainable because the accounting earnings do not recognize any increasing value of real estate holdings and resource reserves. If there is no economic increase in the value of the company's assets then the excess distribution (or dividend) will be a return of capital and the book value of the company will have shrunk by an equal amount. This may result in capital gains which may be taxed differently from dividends representing distribution of earnings.

The distribution of profits by other forms of mutual organization also varies from that of joint-stock companies, though may not take the form of a dividend.

In the case of mutual insurance, for example, in the United States, a distribution of profits to holders of participating life policies is called a dividend. These profits are generated by the investment returns of the insurer's general account, in which premiums are invested and from which claims are paid.[29] The participating dividend may be used to decrease premiums, or to increase the cash value of the policy.[30] Some life policies pay nonparticipating dividends. As a contrasting example, in the United Kingdom, the surrender value of a with-profits policy is increased by a bonus, which also serves the purpose of distributing profits. Life insurance dividends and bonuses, while typical of mutual insurance, are also paid by some joint stock insurers.

Insurance dividend payments are not restricted to life policies. For example, general insurer State Farm Mutual Automobile Insurance Company can distribute dividends to its vehicle insurance policyholders.[31]

See also

- Citizen's dividend

- Common stock dividend

- CSS dividend policy

- Dividend units

- Dividend yield

- Employee stock ownership

- Liquidating dividend

- List of companies paying scrip dividends

- Qualified dividend

References

- O'Sullivan, Arthur; Sheffrin, Steven M. (2003). Economics: Principles in Action. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458: Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-13-063085-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Meritt, Cam. "Corporate Taxation When Issuing Dividends". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- "dividend". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. 2001. Retrieved November 9, 2006.

- Freedman, Roy S.: Introduction to Financial Technology. (Academic Press, 2006, ISBN 0123704782)

- DK Publishing (Dorling Kindersley): The Business Book (Big Ideas Simply Explained). (DK Publishing, 2014, ISBN 1465415858)

- Chambers, Clem (July 14, 2006). "Who needs stock exchanges?". MondoVisione.com. Retrieved May 14, 2017.

- "Stock Splits and Stock Dividends Management".

- "Stock Dividend".

- "Exhibit 5, LLC" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022.

- U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Archived January 3, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- CFA, Elvis Picardo (November 25, 2003). "Payout Ratio". Investopedia. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- "SEC.gov - Ex-Dividend Dates: When Are You Entitled to Stock and Cash Dividends". www.sec.gov.

- Staff, Investopedia (June 7, 2007). "Dividend Frequency". Investopedia. Retrieved August 4, 2018.

- "Dividend Declarations Explained: Process, Significance, Impact". December 10, 2021. Retrieved February 2, 2022.

- "Definition of 'Dividend'". The Economic Times. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- Modak, Samie (March 3, 2016). "Companies rush to announce dividends to avoid tax outgo in April". Business Standard India. Retrieved October 31, 2020.

- "Dividend Tax or Withholding Tax in Various Countries". July 6, 2022. Retrieved July 6, 2022.

- Robert D. Arnott & Clifford S. Asness (January–February 2003). "Surprise! Higher Dividends equal Higher Earnings Growth". Financial Analysts Journal. SSRN 390143.

- Benjamin Graham and David Dodd (1934; Sixth Edition, 2009). McGraw-Hill, p. 367

- P.N. Patel, et al., High Yield, Low Payout. Credit Suisse Quantitative Research, August 2006.

- A. Michael Keppler. The Importance of Dividend Yields in Country Selection. Financial Analyst Journal, Winter 1991

- Levis, Mario (September 1, 1989). "Stock market anomalies: A re-assessment based on the UK evidence". Journal of Banking & Finance. 13 (4): 675–696. doi:10.1016/0378-4266(89)90037-X.

- David Dreman (1998). Contrarian Investment Strategies: The Next Generation. Free Press, ISBN 0684813505

- Jeremy Siegel (2005. The Future for Investors: Why the Tried and the True Triumph Over the Bold and the New. Currency, ISBN 140008198X

- "Ace Hardware, Form 10-K405, Filing Date Mar 22, 2001". secdatabase.com. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Co-op pays out £19.6m in 'divi'". BBC News via bbc.co.uk. June 28, 2007. Retrieved May 15, 2008.

- Nikola Balnave & Greg Patmore. "The History Cooperative – Conference Proceedings - ASSLH - Rochdale consumer co-operatives and Australian labour history". Archived from the original on October 4, 2008.

- Norris, Sue (March 3, 2007). "Cooperatives pay big dividends". The Guardian. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- "What Are Dividends?". New York Life. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved April 29, 2008.

In short, the portion of the premium determined not to have been necessary to provide coverage and benefits, to meet expenses, and to maintain the company's financial position, is returned to policyowners in the form of dividends.

- Hoboken, NJ (2002). "24, Investment-Oriented Life Insurance". In Fabozzi, Frank J. (ed.). Handbook of Financial Instruments. Wiley. p. 591. ISBN 978-0-471-22092-3. OCLC 52323583.

- "State Farm Announces $1.25 Billion Mutual Auto Policyholder Dividend". State Farm. March 1, 2007.

External links

- Ex-Dividend Dates: When Are You Entitled to Stock and Cash Dividends – U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission

- Why Should Companies Pay Dividends?

- Dividend Policy from studyfinance.com at the University of Arizona

- The new U.S. dividend tax cut traps from Tennessee CPA Journal, Nov. 2004