Phallus indusiatus

Phallus indusiatus, commonly called the bamboo mushrooms, bamboo pith, long net stinkhorn, crinoline stinkhorn or veiled lady, is a fungus in the family Phallaceae, or stinkhorns. It has a cosmopolitan distribution in tropical areas, and is found in southern Asia, Africa, the Americas, and Australia, where it grows in woodlands and gardens in rich soil and well-rotted woody material. The fruit body of the fungus is characterised by a conical to bell-shaped cap on a stalk and a delicate lacy "skirt", or indusium, that hangs from beneath the cap and reaches nearly to the ground. First described scientifically in 1798 by French botanist Étienne Pierre Ventenat, the species has often been referred to a separate genus Dictyophora along with other Phallus species featuring an indusium. P. indusiatus can be distinguished from other similar species by differences in distribution, size, color, and indusium length.

| Phallus indusiatus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Basidiomycota |

| Class: | Agaricomycetes |

| Order: | Phallales |

| Family: | Phallaceae |

| Genus: | Phallus |

| Species: | P. indusiatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Phallus indusiatus Vent. (1798) | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| |

| Phallus indusiatus Mycological characteristics | |

|---|---|

| glebal hymenium | |

| cap is conical | |

| spore print is olive | |

| ecology is saprotrophic | |

| edibility: choice | |

Mature fruit bodies are up to 25 cm (10 in) tall with a conical to bell-shaped cap that is 1.5–4 cm (0.6–1.6 in) wide. The cap is covered with a greenish-brown spore-containing slime, which attracts flies and other insects that eat the spores and disperse them. An edible mushroom featured as an ingredient in Chinese haute cuisine, it is used in stir-fries and chicken soups. The mushroom, grown commercially and commonly sold in Asian markets, is rich in protein, carbohydrates, and dietary fiber. The mushroom also contains various bioactive compounds, and has antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Phallus indusiatus has a recorded history of use in Chinese medicine extending back to the 7th century AD, and features in Nigerian folklore.

Taxonomic history

Phallus indusiatus was initially described by French naturalist Étienne Pierre Ventenat in 1798,[2] and sanctioned under that name by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon in 1801.[3] One author anonymously gave his impressions of Ventenat's discovery in an 1800 publication:

This beautiful species, which is sufficiently characterised to distinguish it from every other individual of the class, is copiously produced in Dutch Guiana, about 300 paces from the sea, and nearly as far from the left bank of the river of Surinam. It was communicated to me by the elder Vaillant,[N 1] who discovered it in 1755 on some raised ground which was never overflowed by the highest tides, and is formed of a very fine white sand, covered with a thin stratum of earth. The prodigious quantity of individuals of this species which grow at the same time, the very different periods of their expansion, the brilliancy and the varied shades of their colours, present a prospect truly picturesque.[4]

The fungus was later placed in a new genus, Dictyophora, in 1809 by Nicaise Auguste Desvaux;[5] it was then known for many years as Dictyophora indusiata.[6] Christian Gottfried Daniel Nees von Esenbeck placed the species in Hymenophallus in 1817, as H. indusiatus.[7] Both genera were eventually returned to synonyms of Phallus and the species is now known again by its original name.[1][6]

Curtis Gates Lloyd described the variety rochesterensis in 1909, originally as a new species, Phallus rochesterensis. It was found in Kew, Australia.[8] A form with a pink-coloured indusium was reported by Vincenzo de Cesati in 1879 as Hymenophallus roseus, and later called Dictyophora indusiata f. rosea by Yosio Kobayasi in 1965;[9] it is synonymous with Phallus cinnabarinus.[10] A taxon described in 1936 as Dictyophora lutea[11] and variously known for years as Dictyophora indusiata f. lutea, D. indusiata f. aurantiaca, or Phallus indusiatus f. citrinus, was formally transferred to Phallus in 2008 as a distinct species, Phallus luteus.[12]

The specific epithet is the Latin adjective indūsǐātus, "wearing an undergarment".[13] The former generic name Dictyophora is derived from the Ancient Greek words δίκτυον (diktyon, "net"), and φέρω (pherō, "to bear"), hence "bearing a net".[5][14] Phallus indusiatus has many common names based on its appearance, including long net stinkhorn, crinoline stinkhorn,[15] basket stinkhorn,[16] bridal veil fungus,[17] and veiled lady. The Japanese name Kinugasatake (衣笠茸 or キヌガサタケ), derived from the word kinugasa, refers to the wide-brimmed hats that featured a hanging silk veil to hide and protect the wearer's face.[18] A Chinese common name that alludes to its typical growth habitat is "bamboo mushroom" (simplified Chinese: 竹荪; traditional Chinese: 竹蓀; pinyin: zhúsūn).[19]

Description

Immature fruit bodies of P. indusiatus are initially enclosed in an egg-shaped to roughly spherical subterranean structure encased in a peridium. The "egg" ranges in color from whitish to buff to reddish-brown, measures up to 6 cm (2.4 in) in diameter, and usually has a thick mycelial cord attached at the bottom.[16] As the mushroom matures, the pressure caused by the enlargement of the internal structures cause the peridium to tear and the fruit body rapidly emerges from the "egg". The mature mushroom is up to 25 cm (9.8 in) tall and girded with a net-like structure called the indusium (or less technically a "skirt") that hangs down from the conical to bell-shaped cap. The netlike openings of the indusium may be polygonal or round in shape.[20] Well-developed specimens have an indusium that reaches to the volva and flares out somewhat before collapsing on the stalk.[21] The cap is 1.5–4 cm (0.6–1.6 in) wide and its reticulated (pitted and ridged) surface is covered with a layer of greenish-brown and foul-smelling slime, the gleba, which initially partially obscures the reticulations. The top of the cap has a small hole.[16] The stalk is 7–25 cm (2.8–9.8 in) long,[20] and 1.5–3 cm (0.6–1.2 in) thick. The hollow stalk is white, roughly equal in width throughout its length, sometimes curved, and spongy. The ruptured peridium remains as a loose volva at the base of the stalk.[16] Fruit bodies develop during the night,[22] and require 10–15 hours to fully develop after emerging from the peridium.[23] They are short-lived, typically lasting no more than a few days.[22] At that point the slime has usually been removed by insects, leaving the pale off-white, bare cap surface exposed.[20] Spores of P. indusiatus are thin-walled, smooth, elliptical or slightly curved, hyaline (translucent), and measure 2–3 by 1–1.5 μm.[24]

Similar species

Phallus multicolor is similar in overall appearance, but it has a more brightly coloured cap, stem and indusium, and it is usually smaller. It is found in Australia, Guam, Sumatra, Java, Borneo, Papua New Guinea, Zaire, and Tobago [25] as well as Hawaii. The cap of the Indo-Pacific species P. merulinus appears smooth when covered with gleba, and is pale and wrinkled once the gleba has worn off. In contrast, the cap surface of P. indusiatus tends to have conspicuous reticulations that remain clearly visible under the gleba. Also, the indusium of P. merulinus is more delicate and shorter than that of P. indusiatus, and is thus less likely to collapse under its own weight.[26] Common in eastern North America and Japan, and widely recorded in Europe,[27] the species P. duplicatus has a smaller indusium that hangs 3–6 cm (1.2–2.4 in) from the bottom of the cap, and sometimes collapses against the stalk.[28]

Found in Asia, Australia, Hawaii, southern Mexico, and Central and South America,[10] P. cinnabarinus grows to 13 cm (5.1 in) tall, and has a more offensive odor than P. indusiatus. It attracts flies from the genus Lucilia (family Calliphoridae), rather than the house flies of the genus Musca that visit P. indusiatus.[29] P. echinovolvatus, described from China in 1988, is closely related to P. indusiatus, but can be distinguished by its volva that has a spiky (echinulate) surface, and its higher preferred growth temperature of 30 to 35 °C (86 to 95 °F).[30] P. luteus, originally considered a form of P. indusiatus, has a yellowish reticulate cap, a yellow indusium, and a pale pink to reddish-purple peridium and rhizomorphs. It is found in Asia and Mexico.[12]

Ecology and distribution

The range of Phallus indusiatus is tropical, including Africa (Congo,[21] Nigeria,[31] Uganda,[32] and Zaire[33]) South America (Brazil[24] Guyana,[34] and Venezuela[35]), Central America (Costa Rica),[36] and Tobago.[37] In North America, its range is restricted to Mexico.[38] Asian localities include Indonesia, Nepal, Malaysia,[39] India,[8] Southern China, Japan,[22] and Taiwan.[40] It has also been collected in Australia.[41]

Like all Phallus species, P. indusiatus is saprobic—deriving nutrients from breaking down wood and plant organic matter. The fruit bodies grow singly or in groups in disturbed ground and among wood chips. In Asia, it grows among bamboo forests, and typically fruits after heavy rains.[22][42] The method of reproduction for stinkhorns, including P. indusiatus, is different from most agaric mushrooms, which forcibly eject their spores. Stinkhorns instead produce a sticky spore mass that has a sharp, sickly-sweet odor of carrion.[43] The cloying stink of mature fruit bodies—detectable from a considerable distance—is attractive to certain insects.[22] Species recorded visiting the fungus include stingless bees of the genus Trigona,[44] and flies of the families Drosophilidae and Muscidae. Insects assist in spore dispersal by consuming the gleba and depositing excrement containing intact spores to germinate elsewhere.[22] Although the function of the indusium is not known definitively, it may visually entice insects not otherwise attracted by the odour, and serve as a ladder for crawling insects to reach the gleba.[45]

Edibility and cultivation

In eastern Asia, P. indusiatus is considered a delicacy and an aphrodisiac.[46] Previously only collected in the wild, where it is not abundant, it was difficult to procure. The mushroom's scarcity meant that it was usually reserved for special occasions. In the time of China's Qing Dynasty, the species was collected in Yunnan Province and sent to the Imperial Palaces to satisfy the appetite of Empress Dowager Cixi, who particularly enjoyed meals containing edible fungi.[47] It was one of the eight featured ingredients of the "Bird's Nest Eight Immortals Soup" served at a banquet to celebrate her 60th birthday. This dish, served by descendants of the Confucius family in celebrations and longevity banquets, contained ingredients that were "all precious food, delicacies from land and sea, fresh, tender, and crisp, appropriately sweet and salty".[48] Another notable use was a state banquet held for American diplomat Henry Kissinger on his visit to China to reestablish diplomatic relations in the early 1970s.[49] One source writes of the mushroom: "It has a fine and tender texture, fragrance and is attractive, beautiful in shape, fresh and crispy in taste."[50] The dried fungus, commonly sold in Asian markets, is prepared by rehydrating and soaking or simmering in water until tender.[51] Sometimes used in stir-frys, it is traditionally used as a component of rich chicken soups.[52] The rehydrated mushroom can also be stuffed and cooked.[53]

Phallus indusiatus has been cultivated on a commercial scale in China since 1979.[49] In the Fujian Province of China—known for a thriving mushroom industry that cultivates 45 species of edible fungi—P. indusiatus is produced in the counties of Fuan, Jianou, and Ningde.[54] Advances in cultivation have made the fungus cheaper and more widely available; in 1998, about 1,100 metric tons (1,100 long tons; 1,200 short tons) were produced in China.[15] The Hong Kong price for a kilogram of dried mushrooms reached around US $770 in 1982, but had dropped to US $100–200 by 1988. Additional advances led to it dropping further to US $10–20 by 2000.[49] The fungus is grown on agricultural wastes—bamboo-trash sawdust covered with a thin layer of non-sterilised soil. The optimal temperature for the growth of mushroom spawn and fruit bodies is about 24 °C (75 °F), with a relative humidity of 90–95%.[55] Other substrates that can be used for the cultivation of the fungus include bamboo leaves and small stems, soybean pods or stems, corn stems, and willow leaves.[56]

Nutritional analyses of P. indusiatus show that the fruit bodies are over 90% water, about 6% fiber, 4.8% protein, 4.7% fat, and several mineral elements, including calcium, although the mineral composition in the fungus may depend on corresponding concentrations in the growth substrate.[57]

Folklore

According to ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson, P. indusiatus was consumed in Mexican divinatory ceremonies on account of its suggestive shape. On the other side of the globe, New Guinea natives consider the mushroom sacred.[58] In Nigeria, the mushroom is one of several stinkhorns given the name Akufodewa by the Yoruba people. The name is derived from a combination of the Yoruba words ku ("die"), fun ("for"), ode ("hunter"), and wa ("search"), and refers to how the mushroom's stench can attract hunters who mistake its odour for that of a dead animal.[59] The Yoruba have been reported to have used it as a component of a charm to make hunters less visible in times of danger. In other parts of Nigeria, they have been used in the preparation of harmful charms by ethnic groups such as the Urhobo and the Ibibio people. The Igbo people of east-central Nigeria called stinkhorns éró ḿma, from the Igbo words for "mushroom" and "beauty".[31]

Bioactive properties

Medicinal properties have been ascribed to Phallus indusiatus from the time of the Chinese Tang Dynasty when it was described in pharmacopoeia. The fungus was used to treat many inflammatory, stomach, and neural diseases. Southern China's Miao people continue to use it traditionally for a number of afflictions, including injuries and pains, cough, dysentery, enteritis, leukemia, and feebleness, and it has been prescribed clinically as a treatment for laryngitis, leucorrhea, fever, and oliguria (low urine output), diarrhea, hypertension, cough, hyperlipidemia, and in anticancer therapy.[60] Modern science has probed the biochemical basis of these putative medicinal benefits.

The fruit bodies of the fungus contain biologically active polysaccharides. A β-D-glucan called T-5-N and prepared from alkaline extracts[61] has been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties.[62] Its chemical structure is a linear chain backbone made largely of α-1→3 linked D-mannopyranosyl residues, with traces of 1→6 linked D-mannopyrosyl residues.[63] The polysaccharide has tumour-suppressing activity against subcutaneously implanted sarcoma 180 (a transplantable, non-metastasizing connective tissue tumour often used in research) in mice.[62][64]

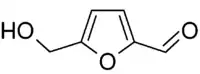

Another chemical of interest found in P. indusiatus is hydroxymethylfurfural,[65] which has attracted attention as a tyrosinase inhibitor. Tyrosinase catalyzes the initial steps of melanogenesis in mammals, and is responsible for the undesirable browning reactions in damaged fruits during post-harvest handling and processing,[66] and its inhibitors are of interest to the medical, cosmetics, and food industries. Hydroxymethylfurfural, which occurs naturally in several foods, is not associated with serious health risks.[65] P. indusiatus also contains a unique ribonuclease (an enzyme that cuts RNA into smaller components) possessing several biochemical characteristics that differentiate it from other known mushroom ribonucleases.[67]

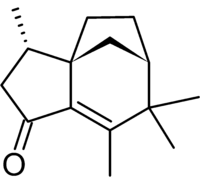

Two novel sesquiterpenes, dictyophorine A and B, have been identified from the fruit bodies of the fungus. These compounds, based on the eudesmane skeleton (a common structure found in plant-derived flavours and fragrances), are the first eudesmane derivatives isolated from fungi and were found to promote the synthesis of nerve growth factor in astroglial cells.[68] Related compounds isolated and identified from the fungus include three quinazoline derivatives (a class of compounds rare in nature), dictyoquinazol A, B, and C.[69] These chemicals were shown in laboratory tests to have a protective effect on cultured mouse neurons that had been exposed to neurotoxins.[70] A total synthesis for the dictyoquinazols was reported in 2007.[71]

The fungus has long been recognised to have antibacterial properties: the addition of the fungus to soup broth was known to prevent it from spoiling for several days.[72] One of the responsible antibiotics, albaflavenone, was isolated in 2011. It is a sesquiterpenoid that was already known from the soil bacterium Streptomyces albidoflavus.[72] Experiments have shown that extracts of P. indusiatus have antioxidant in addition to antimicrobial properties.[73]

A 2001 publication in the International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms attempted to determine its efficacy as an aphrodisiac. In the trial involving sixteen women, six self-reported the experience of a mild orgasm while smelling the fruit body, and the other ten, who received smaller doses, self-reported an increased heart rate. All of the twenty men tested considered the smell displeasing. The study used fruit bodies found in Hawaii, not the edible variety cultivated in China.[74] The study has received criticism. A way to achieve instant orgasms would be expected to gain much attention and many attempts to reproduce the effect, but none has succeeded. No major science journal has published the study, and there are no studies where the results have been reproduced.[75][76]

Notes and references

Notes

- Father of the more famous François Levaillant, explorer and ornithologist, the elder Levaillant was a merchant of Metz who served as French consul in Dutch Guiana until 1763.

References

- "Hymenophallus indusiatus (Vent.) Nees 1817". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2010-10-19.

- Ventenat ÉP. (1798). "Dissertation sur le genre Phallus" [Essay on the genus Phallus]. Mémoires de l'institut National des Sciences et Arts (in French). 1: 503–23.

- Persoon CH. (1801). Synopsis Methodica Fungorum [Synopsis of a Methodology of Mushrooms] (in Latin). Göttingen, Germany: Apud H. Dieterich. p. 244.

- Anonymous (1800). "XXVII. A dissertation on the genus Phallus, by M. Ventenat". The Critical Review, or, Annals of Literature. London, UK. 13: 501–2.

- Desvaux NA. (1809). "Observations sur quelques genres à établir dans la famille des champignons" [Observations on several genera to establish families of mushrooms]. Journal de Botanique (Desvaux) (in French). 2: 88–105.

- Kirk PM, Cannon PF, Minter DW, Stalpers JA (2008). Dictionary of the Fungi (10th ed.). Wallingford, UK: CAB International. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-85199-826-8.

- Nees von Esenbeck CDG. (1817). System der Pilze und Schwämme [System of Mushrooms and Fungi] (in German). Würzburg, Germany: In der Stahelschen buchhandlung. p. 251.

- Lloyd CG. (1909). "Synopsis of the known phalloids". Bulletin of the Lloyd Library of Botany, Pharmacy and Materia Medica (13): 1–96.

- "Dictyophora indusiata f. rosea (Ces.) Kobayasi 1965". MycoBank. International Mycological Association. Retrieved 2012-08-13.

- Kuo M. (April 2011). "Phallus cinnabarinus". MushroomExpert.com. Retrieved 2012-09-13.

- Liou TN, Hwang FY (1936). "Notes sur les Phallidés de Chine" [Notes on the phalloids of China]. Chinese Journal of Botany (in French). 1: 83–95.

- Kayua T. (2008). "Phallus luteus comb. nov., a new taxonomic treatment of a tropical phalloid fungus". Mycotaxon. 106: 7–13. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- Simpson DP. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London, UK: Cassell. p. 883. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- Liddell HG, Scott R (1940). A Greek-English Lexicon (9th unabridged ed.). Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- Hall (2003), p. 19.

- Arora D. (1986). Mushrooms Demystified: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fleshy Fungi. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press. p. 770. ISBN 0-89815-169-4.

- Habtemariam S. (2019). "The Chemistry, Pharmacology and Therapeutic Potential of the Edible Mushroom Dictyophora indusiata (Vent ex. Pers.) Fischer (Synn. Phallus indusiatus)". Biomedicines. 7 (4): 98. doi:10.3390/biomedicines7040098. PMC 6966625. PMID 31842442.

- Inoki L. (June 7, 2006). "Kinugasatake (Veiled lady mushroom)". The Japan Times. Retrieved 2012-09-13.

- Ying J, Mao X, Ma Q, Zong Y, Wen H (1987). Icones of Medicinal Fungi from China. Beijing, China: Science Press. p. 471.

- Chang & Miles (2004), p. 344.

- Dissing H, Lange M (1962). "Gasteromycetes of Congo". Bulletin du Jardin botanique de l'État à Bruxelles. 32 (4): 325–416. doi:10.2307/3667249. JSTOR 3667249.

- Tuno N. (1998). "Spore dispersal of Dictyophora fungi (Phallaceae) by flies". Ecological Research. 13 (1): 7–15. doi:10.1046/j.1440-1703.1998.00241.x. S2CID 620052.

- Chang & Miles (2004), p. 348.

- Trierveiler-Pereira L, Gomes-Silva AC, Baseia IG (2009). "Notes on gasteroid fungi of the Brazilian Amazon rainforest". Mycotaxon. 110: 73–80. doi:10.5248/110.73.

- Burk WR, Smith DR (1978). "Dictyophora multicolor, new to Guam". Mycologia. 70 (6): 1258–9. doi:10.2307/3759327. JSTOR 3759327. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- Reid DA. (1977). "Some Gasteromycetes from Trinidad and Tobago". Kew Bulletin. 31 (3): 657–90. doi:10.2307/4119418. JSTOR 4119418.

- Kibby G, McNeill D (2012). "Phallus duplicatus new to Britain". Field Mycology. 13 (3): 86–9. doi:10.1016/j.fldmyc.2012.06.009.

- Kuo M. (April 2011). "Phallus duplicatus". MushroomExpert.com. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- Lee WS. (1957). "Two new phalloids from Taiwan". Mycologia. 49 (1): 156–8. doi:10.2307/3755742. JSTOR 3755742. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- Zeng DR, Hu ZX, Zhou CL (1988). "A thermophilic delicious 'veiled lady' – Dictyophora echino-volvata Zang, Zheng & Hu [Abstract]". Zhongguo Shiyongjun (Edible Fungi of China) (in Chinese). 4: 5–6.

- Oso BA. (1976). "Phallus aurantiacus from Nigeria". Mycologia. 68 (5): 1076–82. doi:10.2307/3758723. JSTOR 3758723. PMID 995138. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- Maitland TD, Wakefield EM (1917). "Notes on Uganda fungi. I.: The fungus-flora of the forests". Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew). 1917 (1): 1–19. doi:10.2307/4113409. JSTOR 4113409.

- Demoulin V, Dring DM (1975). "Gasteromycetes of Kivu (Zaire), Rwanda and Burundi". Bulletin du Jardin botanique national de Belgique / Bulletin van de National Plantentuin van België. 45 (3/4): 339–72. doi:10.2307/3667488. JSTOR 3667488.

- Wakefield E. (1934). "Contributions to the flora of tropical America: XXI. Fungi collected in British Guiana, chiefly by the Oxford University Expedition, 1929". Bulletin of Miscellaneous Information (Royal Gardens, Kew). 1934 (6): 238–58. doi:10.2307/4115405. JSTOR 4115405.

- Dennis RWG. (1960). "Fungi venezuelani: III". Kew Bulletin. 14 (3): 418–58. doi:10.2307/4114758. JSTOR 4114758.

- Sáenz JA, Nassar M (1982). "Hongos de Costa Rica: Familias Phallaceae y Clathraceae" [Mushrooms of Costa Rica: families Phallaceae and Clathraceae]. Revista de Biología Tropical (in Spanish). 30 (1): 41–52. ISSN 0034-7744. Retrieved 2012-08-28.

- Dennis RWG. (1953). "Some West Indian Gasteromycetes". Kew Bulletin. 8 (3): 307–28. doi:10.2307/4115517. JSTOR 4115517.

- Guzmán G. (1973). "Some distributional relationships between Mexican and United States mycofloras". Mycologia. 65 (6): 1319–30. doi:10.2307/3758146. JSTOR 3758146. PMID 4773309. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-08-24.

- Oldridge SG, Pegler DN, Reid DA, Spooner BM (1986). "A collection of fungi from Pahang and Negeri Sembilan (Malaysia)". Kew Bulletin. 41 (4): 855–72. doi:10.2307/4102987. JSTOR 4102987.

- Chang TT, Chou WN, Wu SH (2000). 福山森林之大型擔子菌資源及監測種之族群變動 [Inventory of macrobasidiomycota and population dynamics of some monitored species at Fushan forest]. Fungal Science (in Chinese). 15 (1/2): 15–26. ISSN 1013-2732.

- Smith KN. (2005). A Field Guide to the Fungi of Australia. Sydney, Australia: UNSW Press. p. 200. ISBN 0-86840-742-9.

- Hall (2003), p. 247.

- Chang & Miles (2004), p. 346.

- Oliveira ML, Morato EF (2000). "Stingless bees (Hymenoptera, Meliponini) feeding on stinkhorn spores (Fungi, Phallales): robbery or dispersal?" (PDF). Revista Brasileira de Zoologia. 17 (3): 881–4. doi:10.1590/S0101-81752000000300025.

- Kibby G. (1994). An Illustrated Guide to Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America. London, UK: Lubrecht & Cramer. p. 155. ISBN 0-681-45384-2.

- Roberts P, Evans S (2011). The Book of Fungi. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 545. ISBN 978-0-226-72117-0.

- Hu (2005), pp. 94–5.

- Hu (2005), p. 96.

- Chang & Miles (2004), p. 343.

- Hu (2005), p. 110.

- Halpern GM. (2007). Healing Mushrooms. Garden City Park, New York: Square One Publishers. pp. 115–6. ISBN 978-0-7570-0196-3.

- Dunlop F. (2003). Sichuan Cookery. London, UK: Penguin Books. p. lxii. ISBN 978-0-14-029541-2.

- Newman JM. (1999). "Bamboo mushrooms". Flavor & Fortune. 6 (4): 25, 30.

- Hu D. (2004). Mushroom industries in China "small mushroom & big business" (PDF) (Report). Wageningen, Netherlands: Wageningen University and Research Centre, Agricultural Economics Research Institute, LEI BV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-24.

- Yang QY, Jong SC (1987). "Artificial cultivation of the veiled lady mushroom, Dictyophora indusiata". In Wuest PJ, Royse DJ, Beelman RB (eds.). Cultivating Edible Fungi: International Symposium on Scientific and Technical Aspects of Cultivating Edible Fungi (IMS 86), July 15–17, 1986. Developments in Crop Science, 10. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Science Publishers. pp. 437–42. ISBN 0-444-42747-3.

- Zhou FL, Qiao CS (1989). "Initial research on the rapid cultivation of Dictyophora indusiata [Abstract]". Zhongguo Shiyongjun (Edible Fungi of China) (in Chinese). 1: 17–8.

- Sitinjak RR. (2017). "The Nutritional Content of the Mushroom Phallus indusiatus Vent., which Grows in the Cocoa Plantation, Gaperta-Ujung, Medan" (PDF). Der Pharma Chemica. 9 (15): 44–47.

- Spooner B, Læssøe T (1994). "The folklore of 'Gasteromycetes'". Mycologist. 8 (3): 119–23. doi:10.1016/S0269-915X(09)80157-2.

- Oso BA. (1975). "Mushrooms and the Yoruba people of Nigeria". Mycologia. 67 (2): 311–9. doi:10.2307/3758423. JSTOR 3758423. PMID 1167931. Archived from the original on 2015-09-23. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- Ker Y-B, Chen K-C, Peng C-C, Hsieh C-L, Peng RY (2011). "Structural characteristics and antioxidative capability of the soluble polysaccharides present in Dictyophora indusiata (Vent. Ex Pers.) Fish Phallaceae" (PDF). Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011: 396013. doi:10.1093/ecam/neq041. PMC 3136395. PMID 21799678.

- Ukai S, Hara C, Kiho T (1982). "Polysaccharides in fungi. IX. a β-D-glucan from alkaline extract of Dictyophora indusiata Fisch" (PDF). Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 30 (6): 2147–54. doi:10.1248/cpb.30.2147.

- Hara C, Kiho T, Tanaka T, Ukai S (1982). "Anti-inflammatory activity and conformational behavior of a branched (1→3)-β-D-glucan from an alkaline extract of Dictyophora indusiata Fisch". Carbohydrate Research. 110 (1): 77–87. doi:10.1016/0008-6215(82)85027-1. PMID 7172167.

- Ukai S, Hara C, Kiho T, Hirose K (1980). "Polysaccharides in fungi V. Isolation and characterization of a mannan from aqueous ethanol extract of Dictyophora indusiata Fisch". Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 29 (9): 2647–52. doi:10.1248/cpb.28.2647.

- Ukai S, Kiho T, Hara C, Morita M, Goto A, Imaizumi N, Hasegawa Y (1983). "Polysaccharides in fungi. XIII. Anti-tumor activity of various polysaccharides isolated from Dictyophora indusiata, Ganoderma japonicum, Cordyceps cicadae, Auricularia auricula-judae and Auricularia species". Chemical & Pharmaceutical Bulletin. 31 (2): 741–4. doi:10.1248/cpb.31.741. PMID 6883594.

- Sharma VK, Choi J, Sharma N, Choi M, Seo S-Y (2004). "In vitro anti-tyrosinase activity of 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furfural isolated from Dictyophora indusiata". Phytotherapy Research. 18 (10): 841–4. doi:10.1002/ptr.1428. PMID 15551389. S2CID 35657755.

- Chang TS. (2009). "An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 10 (6): 2440–75. doi:10.3390/ijms10062440. PMC 2705500. PMID 19582213.

- Wang H, Ng TB (2003). "A novel ribonuclease from the veiled lady mushroom Dictyophora indusiata". Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 81 (6): 373–7. doi:10.1139/O03-067. PMID 14663503.

- Kawagishi H, Ishiyama D, Mori H, Sakamoto H, Ishiguro Y, Furukawa S, Li J (1997). "Dictyophorines A and B, two stimulators of NGF-synthesis from the mushroom Dictyophora indusiata". Phytochemistry. 45 (6): 1203–5. doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(97)00144-1. PMID 9272967.

- Lee I-K, Yun B-S, Han G, Cho D-H, Kim Y-H, Yoo I-D (2002). "Dictyoquinazols A, B, and C, new neuroprotective compounds from the mushroom Dictyophora indusiata". Journal of Natural Products. 65 (12): 1769–72. doi:10.1021/np020163w. PMID 12502311.

- Liu J-K. (2005). "N-containing compounds of macromycetes" (PDF). Chemical Reviews. 105 (7): 2723–44. doi:10.1021/cr0400818. PMID 16011322. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-07.

- Oh CH, Song CH (2007). "Total synthesis of neuroprotective dictyoquinazol A, B, and C". Synthetic Communications. 37 (19): 3311–17. doi:10.1080/00397910701489537. S2CID 98246389.

- Huang M, Chen X, Tian H, Sun B, Chen H (2011). "Isolation and identification of antibiotic albaflavenone from Dictyophora indusiata (Vent:Pers.) Fischer". Journal of Chemical Research. 35 (1): 659–60. doi:10.3184/174751911X13202334527264. S2CID 96228117.

- Mau J-L, Lin H-C, Song S-F (2002). "Antioxidant properties of several specialty mushrooms". Food Research International. 35 (6): 519–26. doi:10.1016/S0963-9969(01)00150-8.

- Holliday JC, Soule N (2001). "Spontaneous female orgasms triggered by smell of a newly found tropical Dictyphora species". International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 3 (2–3): 162–7. doi:10.1615/intjmedmushr.v3.i2-3.790. ISSN 1521-9437.

- Expedition Ecstasy: Sniffing Out The Truth About Hawai‘i’s Orgasm-Inducing Mushroom

- Can a Rare Hawaiian Mushroom Really Give Women a "Spontaneous Orgasm"?

Cited literature

- Chang S-T, Miles PG (2004). "Dictyophora, formerly for the few". Mushrooms: Cultivation, Nutritional Value, Medicinal Effect, and Environmental Impact (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press. pp. 343–56. doi:10.1201/9780203492086.ch18. ISBN 0-8493-1043-1.

- Hall IR. (2003). Edible and Poisonous Mushrooms of the World. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. ISBN 0-88192-586-1.

- Hu D. (2005). Chinese food culture and mushroom (PDF) (Report). Wageningen, Netherlands: Wageningen University and Research Centre, Agricultural Economics Research Institute, LEI BV.

External links

- YouTube Time-lapse video of P. indusiatus growth