Pulmonary pleurae

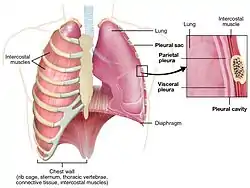

The pulmonary pleurae (sing. pleura)[1] are the two opposing layers of serous membrane overlying the lungs and the inside of the surrounding chest walls.

| Pulmonary pleurae | |

|---|---|

Lung detail showing the pleurae. The pleural cavity is exaggerated since normally there is no space between the pulmonary pleurae. | |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈplʊərə/ |

| System | Respiratory system |

| Nerve | intercostal nerves, phrenic nerves |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | pleurae pulmonarius |

| MeSH | D010994 |

| TA98 | A07.1.02.001 |

| TA2 | 3322 |

| TH | H3.05.03.0.00001 |

| FMA | 9583 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The inner pleura, called the visceral pleura, covers the surface of each lung and dips between the lobes of the lung as fissures, and is formed by the invagination of lung buds into each thoracic sac during embryonic development.[2] The outer layer, called the parietal pleura, lines the inner surfaces of the thoracic cavity on each side of the mediastinum, and can be subdivided into mediastinal (covering the side surfaces of the fibrous pericardium, oesophagus and thoracic aorta), diaphragmatic (covering the upper surface of the diaphragm), costal (covering the inside of rib cage) and cervical (covering the underside of the suprapleural membrane) pleurae. The visceral and the mediastinal parietal pleurae are connected at the root of the lung ("hilum") through a smooth fold known as pleural reflections, and a bell sleeve-like extension of visceral pleura hanging under to the hilum is known as the pulmonary ligament.

Between two pleurae is a potential space called the pleural cavity (also pleural space),[2] which is normally collapsed and filled with only a tiny amount of serous fluid (pleural fluid) secreted by the pleurae, and is clinically considered vacuumous under healthy conditions. The two lungs bounded by parietal pleura, almost fill the thoracic cavity.

Anatomy

_CRUK_306.svg.png.webp)

Each pleura comprises a superficial serosa made of a simple monolayer of flat (squamous) or cuboidal mesothelial cells with microvilli up to 6 μm (0.00024 in) long. The mesothelium is without basement membrane, and supported by a well-vascularized underlying loose connective tissue containing two poorly defined layers of elastin-rich laminae. The costal parietal pleurae also have adipocytes in the subserosa, which present as subpleural/extrapleural fats and are histologically considered belonging to the endothoracic fascia that separates the subserosa from the inner periosteum of the ribs. Both pleurae are quite firmly attached to their underlying structures, and are usually covered by surface glycocalyces that limit fluid loss and reduce friction.

The enclosed space between the parietal and visceral pleurae, known as the pleural space, is normally filled only by a tiny amount (less than 10 mL or 0.34 US fl oz) of serous fluid secreted from the apical region of the parietal pleura. The combination of surface tension, oncotic pressure, and the fluid pressure drop caused by the inward elastic recoil of the lung parenchyma and the rigidity of the chest wall, results in a normally negative pressure of -5 cmH2O (approximately −3.68 mmHg or −0.491 kPa) within the pleural space, causing it to mostly stay collapsed as a potential space that acts as a functionally vacuumous interface between the parietal and visceral pleurae. Contracting the respiratory muscles expands the chest cavity, causing the attached parietal pleura to also expand outwards. If the pleural functional vacuum stays intact, the pleural space will remain as collapsed as possible and cause the visceral pleura to be pulled along outwards, which in turn draws the underlying lung also into expansion. This transmits the pressure negativity into the alveoli and bronchioli, thus facilitating inhalation.[4][5]

Visceral pleura

The visceral pleura (from Latin: viscera, lit. 'organ') covers the lung surfaces and the hilar structures and extends caudally from the hilum as a mesentery-like band called the pulmonary ligament. Each lung is divided into lobes by the infoldings of the pleura as fissures. The fissures are double folds of pleura that section the lungs and help in their expansion,[6] allowing the lung to ventilate more effectively even if parts of it (usually the basal segments) fail to expand properly due to congestion or consolidation.The function of the visceral pleura is to produce and reabsorb fluid.[7] It is an area that is insensitive to pain due to its association with the lung and innervation by visceral sensory neurons.[8]

Visceral pleura also forms interlobular septa (that separates secondary pulmonary lobules).[9] Interlobular septa contains connective tissue, pulmonary veins, and lymphatics.[10]

Parietal pleura

The parietal pleura (from Latin: paries, lit. 'wall') lines the inside of the thoracic cavity which is set apart from the thoracic wall by the endothoracic fascia. The Parietal includes the inner surface of the rib cage and the upper surface of the diaphragm, as well as the side surfaces of the mediastinum, from which it separates the pleural cavity. It joins the visceral pleura at the pericardial base of the pulmonary hilum and pulmonary ligament as a smooth but acutely angled circumferential junction known as the hilar reflection.[11]

The parietal pleura is subdivided according to the surface it covers.

- The costal pleura is the pleural portion covering the inner surfaces of the rib cage, and is separated from the ribs/cartilages and intercostal muscles by the endothoracic fascia.

- The apical part of the costal pleura, sometimes referred to as the cervical pleura or cupula of pleura, bulges beyond the thoracic inlet into the posterior triangle of the neck, where it is covered by an extension of the endothoracic fascia known as the suprapleural membrane. This is the most superficial (and thus most vulnerable) part of the pleura and can be punctured by subclavian catheterization or a penetrating neck injury.

- The diaphragmatic pleura is the portion covering the convex upper surface of the diaphragm. Its junction with the costal pleura at the diaphragmatic margin is a sharp gutter known as the costodiaphragmatic recess, which has diagnostic significance on plain radiography.

- The mediastinal pleura is the portion covering the lateral surfaces of the mediastinum, predominantly the fibrous pericardium, thoracic aorta, superior vena cava/azygos vein, esophagus and (very rarely) an enlarged thymus. Its anterosuperior part (especially of the left side) not infrequently can bulge into the anterior mediastinum behind the upper sternal body and even touch its contralateral counterpart in forced inhalation, but the left and right pleurae do not communicate unless there is a significant injury (traumatic or iatrogenic) or disease process (e.g. malignancy).

Neurovascular supply

As a rule of thumb, the blood and nerve supply of a pleura comes from the structures under it. The visceral pleura is supplied by the capillaries that supply the lung surface (from both the pulmonary circulation and the bronchial vessels), and innervated by the nerve endings from the pulmonary plexus.

The parietal pleura is supplied by blood from the cavity wall under it, which can come from the aorta (intercostal, superior phrenic and inferior phrenic arteries), the internal thoracic arteries (pericardiacophrenic, anterior intercostal and musculophrenic branches), or their anastomoses. Similarly, its nerve supply is from its underlying structures — the costal pleura is innervated by the intercostal nerves; the diaphragmatic pleura is innervated by the phrenic nerve in its central portion around the central tendon, and by the intercostal nerves in its periphery near the costal margin; the mediastinal pleura is innervated by branches of the phrenic nerve over the fibrous pericardium.[12]

Development

The visceral and parietal pleurae, like all mesothelia, both derive from the lateral plate mesoderms. During the third week of embryogenesis, each lateral mesoderm splits into two layers. The dorsal layer joins overlying somites and ectoderm to form the somatopleure; and the ventral layer joins the underlying endoderm to form the splanchnopleure.[13] The dehiscence of these two layers creates a fluid-filled cavity on each side, and with the ventral infolding and the subsequent midline fusion of the trilaminar disc, forms a pair of intraembryonic coeloms anterolaterally around the gut tube during the fourth week, with the splanchnopleure on the inner cavity wall and the somatopleure on the outer cavity wall.

The cranial end of the intraembryonic coeloms fuse early to form a single cavity, which rotates anteriorly and apparently descends inverted in front of the thorax, and is later encroached by the growing primordial heart as the pericardial cavity. The caudal portions of the coeloms fuse later below the umbilical vein to become the larger peritoneal cavity, separated from the pericardial cavity by the transverse septum. The two cavities communicate via a slim pair of remnant coeloms adjacent to the upper foregut called the pericardioperitoneal canal. During the fifth week, the developing lung buds begin to invaginate into these canals, creating a pair of enlarging cavities that encroach into the surrounding somites and further displace the transverse septum caudally — namely the pleural cavities. The mesothelia pushed out by the developing lungs arise from the splanchnopleure, and become the visceral pleurae; while the other mesothelial surfaces of the pleural cavities arise from the somatopleure, and become the parietal pleurae.

Function

As a serous membrane, the pleura secretes a serous fluid (pleural fluid) that contains various lubricating macromolecules such as sialomucin, hyaluronan and phospholipids. These, coupled with the smoothness of the glycocalyces and hydrodynamic lubrication of the pleural fluid itself, reduces the frictional coefficient when the opposing pleural surfaces have to slide against each other during ventilation, thus help improving the pulmonary compliance.

The adhesive property of the pleural fluid to various cellular surfaces, coupled with its oncotic pressure and the negative fluid pressure, also holds the two opposing pleurae in close sliding contact and keeps the pleural space collapsed, maximizing the total lung capacity while maintaining a functional vacuum. When inhalation occurs, the contraction of the diaphragm and the external intercostal muscles (along with the bucket/pump handle movements of the ribs and sternum) increases the volume of the pleural cavity, further increasing the negative pressure within the pleural space. As long as the functional vacuum remains intact, the lung will be drawn to expand along with the chest wall, relaying a negative airway pressure that causes an airflow into the lung, resulting in inhalation. Exhalation is however usually passive, caused by elastic recoil of the alveolar walls and relaxation of respiratory muscles. In forced exhalation, the pleural fluid provides some hydrostatic cushioning for the lungs against the rapid change of pressure within the pleural cavity.[14]

Clinical significance

Pleuritis or pleurisy is a inflammatory condition of pleurae. Due to the somatic innervation of the parietal pleura, pleural irritations, especially if from acute causes, often produce a sharp chest pain that is worse by breathing, known as pleuritic pain.

Pleural disease or lymphatic blockages can lead to a build-up of serous fluid within the pleural space, known as a pleural effusion. Pleural effusion obliterates the pleural vacuum and can collapse the lung (due to hydrostatic pressure), impairing ventilation and leading to type 2 respiratory failure. The condition can be treated by mechanically removing the fluid via thoracocentesis (also known as a "pleural tap") with a pigtail catheter, a chest tube, or a thoracoscopic procedure. Infected pleural effusion can lead to pleural empyema, which can create significant adhesion and fibrosis that require division and decortication. For recurrent pleural effusions, pleurodesis can be performed to establish permanent obliteration of the pleural space.[15]

See also

- Pleural friction rub

References

- "pleura Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". dictionary.cambridge.org.

- Light 2007, p. 1.

- Image by Mikael Häggström, MD. Sources for mentioned features:

- "Mesothelial cytopathology". Libre Pathology. Retrieved 2022-10-18.

- Shidham VB, Layfield LJ (2021). "Introduction to the second edition of 'Diagnostic Cytopathology of Serous Fluids' as CytoJournal Monograph (CMAS) in Open Access". CytoJournal. 18: 30. doi:10.25259/CMAS_02_01_2021. PMC 8813611. PMID 35126608. - Gorman, Niamh, MSc; Salvador, Francesca, MSc (29 October 2020). "The Anatomy of the Pleural cavity". The Ken Hub Library. Dotdash publishing family. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- Sureka, Binit; Thukral, Brij Bhushan; Mittal, Mahesh Kumar; Mittal, Aliza; Sinha, Mukul (October–December 2013). "Radiological review of pleural tumors". Indian Journal of Radiology and Imaging. 23 (4): 313–320. doi:10.4103/0971-3026.125577. PMC 3932573. PMID 24604935.

- Hacking, Craig; Knipe, Henry. "Lung fissures". Radiopaedia. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- Lungs. In: Morton DA, Foreman K, Albertine KH. eds. The Big Picture: Gross Anatomy, 2e. McGraw Hill; Accessed July 12, 2021. https://accessphysiotherapy-mhmedical-com.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/content.aspx?bookid=2478§ionid=202020215

- Lungs. In: Morton DA, Foreman K, Albertine KH. eds. The Big Picture: Gross Anatomy, 2e. McGraw Hill; Accessed July 12, 2021. https://accessphysiotherapy-mhmedical-com.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/content.aspx?bookid=2478§ionid=202020215

- McLoud, Theresa C.; Boiselle, Phillip M. (2010). The Pleura. Elsevier. pp. 379–399. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-02790-8.00018-4. ISBN 978-0-323-02790-8.

- Soldati, Gino; Smargiassi, Andrea; Demi, Libertario; Inchingolo, Riccardo (2020-02-25). "Artifactual Lung Ultrasonography: It Is a Matter of Traps, Order, and Disorder". Applied Sciences. 10 (5): 1570. doi:10.3390/app10051570. ISSN 2076-3417.

- "Parietal pleura". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 2021-06-12.

- Mahabadi, Navid; Goizueta, Alberto A; Bordoni, Bruno (7 February 2021). "Anatomy, Thorax, Lung Pleura And Mediastinum". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. PMID 30085590. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- Larsen, William J. (2001). Human embryology (3. ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Churchill Livingstone. p. 138. ISBN 0-443-06583-7.

- "What Is the Hilum of the Lung?". Health Line. 25 February 2021. Retrieved 2021-06-12.

- Mahabadi, Navid; Goizueta, Alberto A; Bordoni, Bruno (7 February 2021). "Anatomy, Thorax, Lung Pleura And Mediastinum". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. PMID 30085590. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

Sources

- Light, Richard W. (2007). Pleural Diseases. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 978-0781769570.

External links

- thoraxlesson2 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- Atlas image: lung_pleura at the University of Michigan Health System - "X-ray, chest, posteroanterior view"

- Atlas image: lung_lymph at the University of Michigan Health System - "Transverse section through lung"

- MedEd at Loyola Grossanatomy/thorax0/thor_lec/thor6.html

- Diagram at kent.edu