Isle of Portland

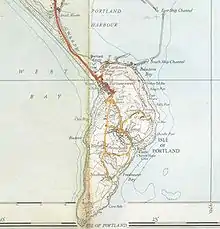

The Isle of Portland is a tied island, 6 kilometres (4 mi) long by 2.7 kilometres (1.7 mi) wide, in the English Channel.[2] The southern tip, Portland Bill lies 8 kilometres (5 mi) south of the resort of Weymouth, forming the southernmost point of the county of Dorset, England. A barrier beach called Chesil Beach joins Portland with mainland England. The A354 road passes down the Portland end of the beach and then over the Fleet Lagoon by bridge to the mainland. The population of Portland is 13,417.[1]

| Isle of Portland | |

|---|---|

| |

Isle of Portland Location within Dorset | |

| Population | 13,417 (2021 est.)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SY690721 |

| • London | 121 miles (195 km) NE |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority |

|

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | PORTLAND |

| Postcode district | DT5 |

| Dialling code | 01305 |

| Police | Dorset |

| Fire | Dorset and Wiltshire |

| Ambulance | South Western |

| UK Parliament |

|

Portland is a central part of the Jurassic Coast, a World Heritage Site on the Dorset and east Devon coast, important for its geology and landforms. Portland stone, a limestone famous for its use in British and world architecture, including St Paul's Cathedral and the United Nations Headquarters, continues to be quarried here.

Portland Harbour, in between Portland and Weymouth, is one of the largest man-made harbours in the world. The harbour was made by the building of stone breakwaters between 1848 and 1905. From its inception it was a Royal Navy base, and played prominent roles during the First and Second World Wars; ships of the Royal Navy and NATO countries worked up and exercised in its waters until 1995. The harbour is now a civilian port and popular recreation area, and was used for the 2012 Olympic Games.

The name Portland is used for one of the British Sea Areas, and has been exported as the name of North American and Australian towns.

History

Portland has been inhabited since at least the Mesolithic period (the Middle Stone Age)—there is archaeological evidence of Mesolithic inhabitants at the Culverwell Mesolithic Site, near Portland Bill,[3] and of habitation since then. The Romans occupied Portland, reputedly calling it Vindelis.[4][5]

Although the beginning of the Viking Age in England is dated to their raid in 793,[6][7] when they destroyed the abbey on Lindisfarne, their first documented landing occurred in Portland four years earlier, in 789, as recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle.[8] Three lost Viking ships from Hordaland (the district around Hardanger fjord in west Norway) landed at Portland Bill. The king's reeve tried to collect taxes from them, but they killed him and sailed on.[9]

A castle on the site of the present Rufus Castle, standing over Church Ope Cove, may have been built for William II of England (also known as William Rufus) soon after the conquest of England by his father William the Conqueror. None of that castle remains; the existing castle probably dates from the 15th century.

In 1539 King Henry VIII ordered the construction of Portland Castle for defence against attacks by the French; the castle cost £4,964[10] (equivalent to £3.55 million in 2022[11]). It is one of the best preserved castles from this period, and is opened to the public by the custodians English Heritage.[12]

In the 17th century, chief architect and Surveyor-General to James I, Inigo Jones, surveyed the area and introduced the local Portland stone to London, using it in his Banqueting House, Whitehall, and for repairs on St Paul's Cathedral.[13] His successor, Sir Christopher Wren, an architect and the Member of Parliament for nearby Weymouth, used six million tons of white Portland limestone to rebuild destroyed parts of the capital after the Great Fire of London of 1666. Well-known buildings in the capital, including St Paul's Cathedral[14] and the eastern front of Buckingham Palace feature the stone.[15] After the First World War, a quarry was opened by The Crown Estate to provide stone for the Cenotaph in Whitehall and half a million gravestones for war cemeteries,[5] and after the Second World War hundreds of thousands of gravestones were hewn for soldiers who had fallen on the Western Front.[5] Portland cement has nothing to do with Portland; it was so named due to its similar colour to Portland stone when mixed with lime and sand.[16]

There have been railways in Portland since the early 19th century. The Merchant's Railway was the earliest—it opened in 1826 (one year after the Stockton and Darlington railway) and ran from the quarries at the north of Tophill to a pier at Castletown, from where the Portland stone was shipped around the country.[17][18] The Weymouth and Portland Railway was laid in 1865, and ran from a station in Melcombe Regis, across the Fleet and along the low isthmus behind Chesil Beach to a station at Victoria Square in Chiswell.[19] At the end of the 19th century the line was extended to the top of the island as the Easton and Church Ope Railway, running through Castletown and ascending the cliffs at East Weares, to loop back north to a station in Easton.[17] The line closed to passengers in 1952, and the final goods train (and two passenger 'specials') ran in April 1965.[19]

The Royal National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck stationed a lifeboat at Portland in 1826, which was withdrawn in 1851.[20] Coastal flooding has affected Portland's residents and transport for centuries—the only way off the island by land is along the causeway in the lee of Chesil Beach. At times of extreme floods (about every 10 years) this road link is cut by floods. The low-lying village of Chiswell used to flood on average every 5 years. Chesil Beach occasionally faces severe storms and massive waves, which have a fetch across the Atlantic Ocean.[21] Following two severe flood events in the 1970s, Weymouth and Portland Borough Council and Wessex Water decided to investigate the structure of the beach, and coastal management schemes that could be built to protect Chiswell and the beach road. In the 1980s it was agreed that a scheme to provide storm protection with a 20% annual exceedance probability to reduce flood depth and duration in more severe storms.[21] Hard engineering techniques were employed in the scheme, including a gabion running 550 metres (600 yd)[22] to the north of Chiswell, an extended sea wall in Chesil Cove, and a culvert running from inside the beach, underneath the beach road and into Portland Harbour, to divert flood water away from low-lying areas.[21]

At the start of the First World War, HMS Hood was sunk in the passage between the southern breakwaters to protect the harbour from torpedo and submarine attack.[23] Portland Harbour was formed (1848–1905) by the construction of breakwaters, but before that the natural anchorage had hosted ships of the Royal Navy for more than 500 years. It was "the home of the Asdics,"[24] a centre for Admiralty research into asdic submarine detection and underwater weapons from 1917 to 1998; the shore base HMS Serepta was renamed HMS Osprey in 1927.[25] During the Second World War Portland was the target of 48 air raids and a total of 532 bombs, although most warships had moved north as Portland was within enemy striking range across the Channel.[26] Mulberry Harbour Phoenix Units can be seen at Black Barge beach, near Portland Castle. Portland was a major embarkation point for Allied forces on D-Day in 1944. Early helicopters were stationed at Portland in 1946–1948, and in 1959 a shallow tidal flat, The Mere, was infilled, and sports fields taken to form a heliport. The station was formally commissioned as HMS Osprey, which then became the largest and busiest military helicopter station in Europe. The base was gradually improved with additional landing areas and one of England's shortest runways, at 229 metres (751 ft).[25]

The naval base closed after the end of the Cold War in 1995, and the Royal Naval Air Station closed in 1999, although the runway remained in use for Her Majesty's Coastguard Search and Rescue flights as MRCC Portland[25] until 2014.[27] MRCC Portland's area of responsibility extended midway across the English Channel, and from Start Point in Devon to the Dorset/Hampshire border, covering an area of around 10,400 square kilometres (4,000 sq mi).[28] The 12 Search and Rescue teams in the Portland area dealt with almost 1000 incidents in 2005.[29] Portland lends its name to one of the BBC's Shipping Forecast regions.

There are still two prisons on Portland: HMP The Verne, which until 1949 was a Victorian military fortress, and a Young Offenders' Institution (HMYOI) on the Grove clifftop.[30] This was the original prison (HM Prison Portland) built for convicts who quarried stone for the Portland Breakwaters from 1848. For a few years until 2005 Britain's only prison ship, HMP The Weare, was berthed in the harbour.[31]

Governance

Portland is in the Dorset unitary authority, administered by Dorset Council. The island forms one of the 52 wards and elects three members to the council.[32]

Portland is an ancient royal manor, and until the 19th century remained a separate liberty within Dorset for administration purposes. It was then an urban district from 1894 to 1974. The borough of Weymouth and Portland formed on 1 April 1974 under the Local Government Act 1972 by merger of Portland urban district with the borough of Weymouth and Melcombe Regis. In 2020, the borough of Weymouth and Portland was abolished when Dorset moved to a unitary authority structure of local government.[33]

Weymouth, Portland and the Purbeck district are in the South Dorset parliamentary constituency, created in 1885. The constituency elects one Member of Parliament; the current MP is Richard Drax (Conservative).[34]

Weymouth and Portland have been twinned with the town of Holzwickede in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany since 1986,[35] and the French town of Louviers, in the department of Eure in Normandy, since 1959.[36] The borough and nearby Chickerell have been a Fairtrade Zone since 2007.[37]

Geography

The Isle of Portland lies in the English Channel, 3 kilometres (2 mi) south of Wyke Regis, and 200 km (120 mi) west-southwest of London, at 50°33′0″N 2°26′24″W (50.55, −2.44). Portland is situated approximately halfway along the UNESCO Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site; the site includes 153 kilometres (95 mi) of the Dorset and east Devon coast that is important for its geology and landforms.[38] The South West Coast Path runs around the coast; it is the United Kingdom's longest national trail at 1,014 kilometres (630 mi). Portland is unusual as it is connected to the mainland at Abbotsbury by Chesil Beach, a tombolo which runs 29 kilometres (18 mi) north-west to West Bay.[39] Portland is sometimes defined incorrectly as a tombolo—in fact Portland is a tied island, and Chesil Beach is the tombolo (a spit joined to land at both ends).[40][41]

There are eight settlements on Portland, the largest being Fortuneswell in Underhill and Easton on Tophill. Castletown and Chiswell are the other villages in Underhill, and Weston, Southwell, Wakeham and the Grove are on the Tophill plateau.[42] Many old buildings are built out of Portland Stone; several parts have been designated Conservation Areas to preserve the unique character the older settlements which date back hundreds of years.[43]

The Isle of Portland has been designated by Natural England as National Character Area 137. It is adjoined by the Weymouth Lowlands to the north.[40]

Geology

Geologically, Portland is separated into two areas; the steeply sloping land at its north end called Underhill, and the larger, gently sloping land to the south, called Tophill. Portland stone lies under Tophill; the strata decline at a shallow angle of around 1.5 degrees, from a height of 151 metres (495 ft) near the Verne in the north, to just above sea level at Portland Bill.[44] The geology of Underhill is different to Tophill; Underhill lies on a steep escarpment composed of Portland Sand, lying above a thicker layer of Kimmeridge Clay, which extends to Chesil Beach and Portland Harbour. This Kimmeridge Clay has resulted in a series of landslides, forming West Weares and East Weares.[44]

2.4 kilometres (1.5 mi) underneath south Dorset lies a layer of Triassic rock salt, and Portland is one of four locations in the United Kingdom where the salt is thick enough to create stable cavities.[45][46] Portland Gas applied to excavate 14 caverns to store 1,000,000,000 cubic metres (3.5×1010 cu ft) of natural gas, which is one percent of the UK's total annual demand.[45][46] It was proposed that the caverns should be connected to the National gas grid at Mappowder via a 37-kilometre (23 mi) pipeline.[45][46] Plans had it that the surface facilities should be complete to store the first gas in 2011, and the entire cavern space available for storage in winter 2013.[46] As part of the £350 million scheme,[45] the Grade II listed former Old Engine Shed would be converted into a £1.5 million educational centre with a café and an exhibition space about the geology of Portland.[47]

Portland Bill

Portland Bill is the southern tip of the island of Portland. The Bill has three lighthouse towers. The Higher Lighthouse is now a dwelling and holiday apartments whilst the Lower Lighthouse is now a bird observatory and field centre providing records of bird migration and accommodation for visitors, which opened in 1961.[48] The white and red lighthouse on Bill Point replaced the Higher and Lower Lighthouses in 1906. It is a prominent and much photographed feature; an important landmark for ships passing the headland and its tidal race. The current lighthouse was refurbished in 1996 and became remotely controlled. It now contains a visitors' centre giving information and guided tours of the lighthouse.[49] As of June 2009, the lighthouse uses a 1 kW metal-halide US-made lamp with an operational life of about 4000 hours, or 14 months.

Portland Ledge and Portland Race

Portland Ledge is an underwater extension of Portland Stone into the English Channel at a place where the depth of Channel is 20 to 40 metres (about 10 to 20 fathoms). Tidal flow is disrupted by the feature; at 10 metres (about 5 fathoms) deep and 2.4 kilometres (1.3 nmi) long, it causes a tidal race to the south of Portland Bill, the so-called Portland Race.[50] The current only stops for brief periods during the 12+1⁄2-hour tidal cycle and can reach 4 metres per second (9 mph) at the spring tide of 2 metres (6 ft 7 in).[50]

Ecology

Due to its isolated coastal location, the Isle of Portland has an extensive range of flora and fauna; the coastline and disused quarries are designated as Sites of Special Scientific Interest.[38][51] The Isle of Portland SSSI encompasses 352 hectares (870 acres), and includes 17 monitored features ranging from Jurassic fossils, calcareous grassland, rock sea-lavender and nationally scarce butterflies.[52] Sea and migratory birds occupy the cliffs in different seasons, sometimes these include rare species which draw ornithologists from around the country.[38][53] Rare visitors to the surrounding seas include dolphins, seals and basking sharks.[51] Chesil Beach is one of only two sites in Britain where the scaly cricket can be found; unlike any other cricket it is wingless and does not sing or hop.[53] Ten British Primitive goats were introduced to the East Weares part of the island to control scrub in 2007.[54]

The comparatively warm and sunny climate allows species of plants to thrive which do not on the mainland. The limestone soil has low nutrient levels; hence smaller species of wild flowers and grasses are able to grow in the absence of larger species.[51] Portland sea lavender can be found on the higher sea cliffs; unique to Portland, it is one of the United Kingdom's rarest plants.[55][52] The wild flowers and plants make an excellent habitat for butterflies; over half of the British Isles' 57 butterfly species can be seen on Portland, including varieties that migrate from mainland Europe.[38] Species live on Portland that are rare in the United Kingdom, including the limestone race of the silver-studded blue.[56]

Climate

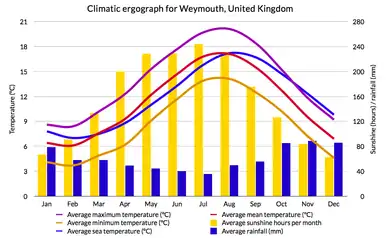

The mild seas which almost surround the tied island produce a temperate climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb) with a small variation in daily and annual temperatures. The average annual mean temperature from 1991 to 2020 was 11.5 °C (52.7 °F).[57] The warmest month is August, which has an average temperature range of 14.8 to 19.5 °C (58.6 to 67.1 °F), and the coolest is February, which has a range of 4.7 to 8.4 °C (40.5 to 47.1 °F).[57] Mean winter temperatures are amongst the highest in the British Isles, and by far warmer than the United Kingdom average. However, due to the island's proximity to the sea, summers are cooler than the national average, with temperatures rarely climbing to the extremes seen in in-land areas further north.[58] As a result of its coastal extremity and mild winter minimum temperatures, Portland is suitable for plants with the Royal Horticultural Society's hardiness rating H2.[59][B] Mean sea surface temperatures range from 7.0 °C (44.6 °F) in February to 17.2 °C (63.0 °F) in August; the annual mean is 11.8 °C (53.2 °F).[60]

| Climate data for Isle of Portland climatic averages | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8.7 (47.7) |

8.4 (47.1) |

9.7 (49.5) |

11.9 (53.4) |

14.5 (58.1) |

17.0 (62.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

19.5 (67.1) |

18.1 (64.6) |

15.0 (59.0) |

11.9 (53.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.9 (44.4) |

6.6 (43.9) |

7.7 (45.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

12.0 (53.6) |

14.6 (58.3) |

16.6 (61.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

10.1 (50.2) |

7.8 (46.0) |

11.5 (52.7) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 5.2 (41.4) |

4.7 (40.5) |

5.6 (42.1) |

7.0 (44.6) |

9.5 (49.1) |

12.2 (54.0) |

14.3 (57.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

11.1 (52.0) |

8.2 (46.8) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 74.1 (2.92) |

52.7 (2.07) |

46.3 (1.82) |

47.6 (1.87) |

42.7 (1.68) |

41.1 (1.62) |

36.9 (1.45) |

47.2 (1.86) |

46.2 (1.82) |

76.4 (3.01) |

82.6 (3.25) |

78.6 (3.09) |

672.3 (26.47) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 12.3 | 10.5 | 9.1 | 8.6 | 8.0 | 7.2 | 6.4 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 12.0 | 13.4 | 12.6 | 116.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 66.7 | 90.5 | 134.0 | 192.2 | 228.5 | 230.3 | 237.4 | 212.4 | 172.5 | 116.1 | 80.1 | 62.2 | 1,822.6 |

| Source: 1991–2020 averages for the Isle of Portland climate station and Weymouth Cefas station. Sources: Met Office[61] and Cefas[60] | |||||||||||||

The mild seas that surround Portland act to keep night-time temperatures above freezing, making air frost rare: on average 6.3 days per year — this is far below the United Kingdom's average annual total of 55.6 days of frost.[57][62] Days with snow lying are equally rare: on average zero to five days per year;[63] almost all winters have no more than one day with snow lying. It may snow or sleet in winter, yet it almost never settles on the ground—coastal areas in South West England such as Portland generally experience the mildest winters in the UK.[64] Portland is less affected by the Atlantic storms that Devon and Cornwall experience. The growing season lasts for more than 310 days per year,[65][D] and the borough is in Hardiness zone 9.[66][E]

Weymouth and Portland, and the rest of the south coast,[67] has the sunniest climate in the United Kingdom.[38][68] Portland averaged 1822.6 hours of sunshine annually between 1991 and 2020,[57] which is 42% of the maximum possible,[C] and 36% above the United Kingdom average of 1402.7 hours.[62] December is the cloudiest month (62.2 hours of sunshine), November the wettest (82.6 millimetres (3.3 in) of rain) and July is the sunniest and driest month (237.4 hours of sunshine, 36.9 millimetres (1.5 in) of rain).[57] Sunshine totals in all months are well above the United Kingdom average,[62] and monthly rainfall totals throughout the year are less than the UK average, particularly in summer;[62] this summer minimum of rainfall is not experienced away from the south coast of England.[67] The average annual rainfall of 672.3 millimetres (26.5 in) is well below the UK average of 1,163.0 millimetres (45.8 in).[57]

Demography

| Religion | %[69][F] |

|---|---|

| Buddhist | 0.4 |

| Christian | 61.0 |

| Hindu | 0.1 |

| Jewish | 0.1 |

| Muslim | 0.5 |

| No religion | 29.3 |

| Other | 0.7 |

| Sikh | 0.1 |

| Not stated | 7.9 |

| Age | Percentage[70] |

|---|---|

| 0–15 | 18.1 |

| 16–17 | 2.4 |

| 18–44 | 33.5 |

| 45–59 | 21.9 |

| 60–84 | 21.7 |

| 85+ | 2.3 |

| Year | Population[70][A][1] |

|---|---|

| 1971 | 12,330 |

| 1981 | 12,410 |

| 1991 | 13,190 |

| 2001 | 12,800 |

| 2010 | 12,400 |

| 2011 | 12,869 |

| 2012 | 12,806 |

| 2013 | 12,966 |

| 2014 | 12,603 |

| 2015 | 12,501 |

| 2016 | 12,627 |

| 2017 | 12,721 |

| 2018 | 12,797 |

| 2021 | 13,417 |

The population of Portland in 2021 was 13,417;[1] this figure has remained around twelve to thirteen thousand since the 1970s. In 2011 there were 6,312 dwellings in an area of 11.5 square kilometres (2,840 acres), with a population density of 1112 people per km2.[1] The population is almost entirely native to the United Kingdom: 93.9 percent of residents are of white British ethnicity,[1] well above the England and Wales average of 80.5 percent.[69] The average price of a detached house on Portland in 2010 was £194,200; terraced houses are cheaper, at £149,727, and an apartment or maisonette costs £110,500.[70][G]

Crime rates are below average—there were 5.4 burglaries per 1000 households in 2009 and 2010; which is lower than South West England (7.6 per 1000) and significantly lower than England and Wales (11.6 per 1000).[70] Unemployment levels are very low, at 1.9 percent in July 2011,[70] compared to the United Kingdom average of 7.7 percent.[71] The most common religious identity in Weymouth and Portland is Christianity, at 61.0 percent, which is slightly above the England and Wales average of 59.3 percent.[69] The next-largest sector is those with no religion, at 29.3 percent, also slightly above the average of 25.1 percent.[69]

Transport

The A354 road is the only land access to Portland, via Ferry Bridge, connecting to Weymouth and to the wider road network at the A35 trunk road in Dorchester. It runs from Easton, splitting into a northbound section through Chiswell and a southbound section through Fortuneswell, then along Chesil Beach and across a bridge to the mainland in Wyke Regis. Formerly the Portland Branch Railway also crossed to the island. The corridor is now a traffic-free walking and cycle path.[72]

Local buses are run by FirstGroup, with services to Weymouth.[73] Weymouth is the hub for south Dorset bus routes, with services to Dorchester and local villages.[73] Weymouth is connected to towns and villages along the Jurassic Coast by the Jurassic Coast Bus service, which runs for 142 kilometres (88 mi) from Exeter to Poole, through Sidford, Beer, Seaton, Lyme Regis, Charmouth, Bridport, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Wool, and Wareham.[74] Trains run from Weymouth to London, Southampton, Bristol and Gloucester but ferries no longer transport passengers to the French port of St Malo and the Channel Islands of Guernsey and Jersey.[75]

Education

St George's Community Primary School is located in Easton.[76] The only other school on Portland is the Atlantic Academy, an all-through school for pupils aged 3 to 19 based at two different sites.[77] Formerly known as the Isle of Portland Aldridge Community Academy, it formed in 2012 by merging four primary schools and one secondary school.[78]

Some students commute to Weymouth or Dorchester to study A-Levels, or to attend other secondary schools nearby. Weymouth College in Melcombe Regis is the nearest further education college, which has around 7,500 students from south west England and overseas,[79] about 1500 studying A-Level courses.[80]

Culture

Sport and recreation

In 2000, the Weymouth and Portland National Sailing Academy was built in Osprey Quay in Underhill as a centre for sailing in the United Kingdom. Weymouth and Portland's waters were credited by the Royal Yachting Association as the best in Northern Europe.[81] Weymouth and Portland regularly host local, national and international sailing events in their waters; these include the J/24 World Championships in 2005, trials for the 2004 Athens Olympics, the ISAF World Championship 2006, the BUSA Fleet Racing Championships, and the RYA Youth National Championships.[82]

In 2005, the WPNSA was selected to host sailing events at the 2012 Olympic Games—mainly because the academy had recently been built, so no new venue would have to be provided.[83] However, as part of the South West of England Regional Development Agency's plans to redevelop Osprey Quay, a new 600-berth marina and an extension with more on-site facilities were built.[84] Construction was scheduled between October 2007 and the end of 2008, and with its completion and formal opening on 11 June 2009, the venue became the first of the 2012 Olympic Games to be completed.[85][86][87][88][89]

Weymouth Bay and Portland Harbour are used for other water sports – the reliable wind is favourable for wind and kite-surfing. Chesil Beach and Portland Harbour are used regularly for angling, scuba diving to shipwrecks, snorkelling, canoeing, and swimming.[90] The limestone cliffs and quarries are used for rock climbing; Portland has areas for bouldering and deep water soloing, however sport climbing with bolt protection is the most common style.[91] Since June 2003 the South West Coast Path National Trail has included 21.3 kilometres (13.2 mi) of coastal walking around the Isle of Portland, including following the A354 Portland Beach Road twice.[92]

Isle of Portland has a Non-League football club Portland United F.C. who play at Grove Corner.[93] They also have a youth set up called Portland United youth football Club.[94]

Rabbits

Rabbits have long been associated with bad luck on Portland. Use of the name is still taboo—the creatures are often referred to as "underground mutton", "long-eared furry things" or just "bunnies".[95] The origin of this superstition is obscure (there is no record of it before the 1920s) but it is believed to derive from quarry workers. They would see rabbits emerging from their burrows immediately before a rock fall and blame them for increasing the risk of dangerous, sometimes deadly, landslides.[96] If a rabbit was seen in a quarry, the workers would go home for the day, until the safety of the area had been assured.[95]

Today older Portland residents are 'offended' (sometimes for the benefit of tourists) by the mention of rabbits;[96] this superstition came to national attention in October 2005 when a special batch of advertisement posters were made for the Wallace and Gromit film, The Curse of the Were-Rabbit. Out of respect for local beliefs the adverts omitted the word 'rabbit' and replaced the film's title with the phrase "Something bunny is going on".[95]

Literature

Thomas Hardy described Portland as "the peninsula carved by Time out of a single stone", and named it the Isle of Slingers and Isle of the Race in his Wessex novels; it was the main setting of The Well-Beloved (1897), and was featured in The Trumpet-Major (1880).[97][98] The cottage that now houses Portland Museum was the inspiration for the heroine's house in The Well-Beloved. Portlanders were expert stone-throwers in the defence of their land, and Hardy's Isle of Slingers is heavily based on Portland; the Street of Wells representing Fortuneswell and The Beal Portland Bill. Hardy also called Portland the Gibraltar of the North, with reference to its similarities with Gibraltar; its physical geography, isolation, comparatively mild climate, and Underhill's winding streets.[99]

A. E. Housman wrote of the place in his poem, "The Isle of Portland", from A Shropshire Lad.

Hilaire Belloc's book The Cruise of the "Nona" is about sailing near Portland, and the reflections it occasions. He describes Portland Race as "the master terror of our world", and says "... if you were to make a list of all the things which Portland Race has swallowed up, it would rival Orcus".[100][101]

In Museums Without Walls, Jonathan Meades declares that "Portland is a bulky chunk of geological, social, topographical and demographic weirdness. It is the obverse of a beauty spot. 'Beauty' in this construction implies the picturesque. Portland is gloriously bereft of this quality. It is awesome. There is nothing pretty about it."[102]

In The Warlord Chronicles (1995–97), Bernard Cornwell makes Portland the Isle of the Dead, a place of internal exile, where the causeway was guarded to keep the 'dead' (people suffering insanity) from crossing the Fleet and returning to the mainland. No historical evidence exists to support this idea.[103]

The Portland Chronicles series of four children's books, set on and around Portland and Weymouth and written by local author Carol Hunt, draw on local history to explore a seventeenth century world of smuggling, witchcraft, piracy and local intrigue.[104]

In the Louis L'Amour novel To the Far Blue Mountains the novel's main character, Barnabas Sackett, hides in Cave Hole at the Bill of Portland before meeting a sailing ship in an attempt to escape from England.

Pink Pippos of Portland, a children's storybook about nearby Chesil Beach was written by Portland author Sandra Fretwell.[105]

Notable people

- Lead singer of rock band Art Brut, Eddie Argos

- Edgar F. Codd (23 August 1923 – 18 April 2003), British computer scientist and inventor of the relational model for database management

- Former Premier League referee Paul Durkin

- Former Queensland, Australia, politician Pat Comben

See also

References

Informational notes

- A The figures for non-census years are estimates.

- B Plants in the Royal Horticultural Society's hardiness rating H2 are tolerant of temperatures as low as 1 °C (34 °F) but will not survive being frozen.

- C The maximum hours of sunshine possible in one year is approximately 4383 hours (12 hours/day × 365.25 days).

- D The growing season in the United Kingdom is defined as starting on the day after five consecutive days with mean temperatures above 5 °C (41 °F). The season finishes the day after mean temperatures are below 5 °C (41 °F) for five consecutive days.[108]

- E Areas in Hardiness zone 9 experience an average lowest recorded temperature each year between −6.6 and −1.1 °C (20.1 and 30.0 °F).[109]

- F Figures are for Weymouth and Portland as a whole.

- G These figures are for July to September in 2010.

Citations

- "Statistics and census information. Area profile for Portland. State of Dorset 2021 report for the Dorset Council area". Dorset Insight. 2021. Archived from the original on 28 January 2022. Retrieved 26 September 2022.

- "Isle of Portland". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2015. Archived from the original on 18 September 2013. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Mesolithic Site, Portland". Association for Portland Archaeology. 2002. Archived from the original on 9 June 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- "Lexicon Universale". Universität Mannheim. 2006. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- "Portland—Dorset". Dorset Guide. 2007. Archived from the original on 5 May 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- "History of Lindisfarne Priory". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- Swanton, Michael (1998). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Psychology Press. ISBN 0-415-92129-5. p. 57, n. 15.

- "What spurred the Viking invasions?". Saxons and Vikings in Britain. Archived from the original on 16 October 2014. Retrieved 3 October 2014.

- "Viking Attacks". web.cn.edu. Archived from the original on 1 January 2016. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- "Portland, Dorset, England". The Dorset Page. 2000. Archived from the original on 12 July 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- "Portland Castle". English Heritage. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 August 2020. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- Rhodes, Frank H. T.; Stone, Richard O. (2013). Language of the Earth. Elsevier. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-4831-6166-2.

- "1710 – Construction is Completed". Dean and Chapter St Paul's. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- "Buckingham Palace History". HM Queen Elizabeth II. 2007. Archived from the original on 7 February 2009. Retrieved 3 April 2007.

- "History & Manufacture of Portland Cement". Portland Cement Association. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 October 2013. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- "Railways of the Weymouth area". Island Publishing. 2005. Archived from the original on 3 April 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- Morris, Stuart (2016). "Portland, an Illustrated History". The Dovecote Press. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 10 October 2016.

- "Weymouth to Portland Railway, Construction and growth". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- Denton, Tony (2009). Handbook 2009. Shrewsbury: Lifeboat Enthusiasts Society. p. 59.

- "Chiswell case study: The Scheme". Jurassic Coast. 2007. Archived from the original on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- "Chiswell Gabions Flood Alleviation Scheme" (PDF). Environment Agency. 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2014. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- "Turret Battleship, HMS Hood". Cranston Fine Arts. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- Winston S. Churchill, The Second World War, vol. 1, The Gathering Storm (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1948), p. 501.

- "Portland Base/Heliport History". helis.com. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- Mutch, Roger (October 2012). "Danger UXB – Portland's World War 2 UneXploded Bomb". Dorset Life. Archived from the original on 27 January 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- "Portland Coastguard centre to close next month, MCA confirms". mby.com. 2014. Archived from the original on 17 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- "Coastguard Rescue Helicopter". Beer Coastguard. 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- "Eastern Region – Area South". Maritime and Coastguard Agency. 2007. Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- "HMP/YOI Portland information". Justice.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 24 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Morris, Steven (12 August 2005). "Britain's only prison ship ends up on the beach | UK news". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Your Councillors". Dorset Council. Archived from the original on 21 October 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- "New councils take control in Dorset". BBC News. 1 April 2019. Archived from the original on 18 May 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- "Dorset South". The Guardian. 2010. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 19 June 2010.

- "Städtepartnerschaften in Holzwickede" (in German). Gemeinde Holzwickede. 2007. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- "Associations de jumelage" (in French). Ville de Louviers. 2007. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2007.

- "Weymouth & Portland: a Fairtrade Zone". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 2008. Archived from the original on 29 October 2007. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- "Portland". Jurassic Coast. 2006. Archived from the original on 14 September 2007. Retrieved 29 December 2007.

- "The Chesil Beach – General Introduction". Southampton University. 2007. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 13 August 2007.

- "Isle of Portland/Weymouth Lowlands" (PDF). Natural England. 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- "Coastal Landform Definitions". Villanova College. 2007. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- "A portrait of Portland". Dorset Life. Archived from the original on 18 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Conservation areas – Weymouth and Portland". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "General Geology". Southampton University. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- "Island may be key gas supplier". Dorset Echo. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- "Portland gas storage project". Portland Gas. 2007. Archived from the original on 29 July 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- "Island may get a £1.5m visitor centre". Dorset Echo. 2007. Archived from the original on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 5 December 2007.

- Stuart Morris, 2016 Portland, an Illustrated History The Dovecote Press, Wimborne, Dorset: ISBN 978-0-9955462-0-2

- "Portland Bill Lighthouse". Trinity House. 2007. Archived from the original on 9 August 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2007.. * Stuart Morris, 2016 Portland, an Illustrated History The Dovecote Press, Wimborne, Dorset: ISBN 978-0-9955462-0-2

- "Offshore Geology". Southampton University. 2007. Archived from the original on 12 May 2020. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- "Portland wildlife". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- "Isle Of Portland SSSI". Designated Sites View. Natural England. 4 August 2020. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- "Chesil Beach". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- "Wildlife on Portland" (PDF). Heights Hotel and Swarovski Optik. Spring 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2012.

- "Coastal Flora & Fauna". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- "Portland Butterflies". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 2007. Archived from the original on 13 May 2007. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- "Station: Isle of Portland". Met Office. 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- "England 1971–2000 averages". Met Office. 2001. Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2007.

- "RHS hardiness rating". RHS hardiness rating. Royal Horticultural Society. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2020.

- "Cefas Station 24: Weymouth". The Centre for Environment Fisheries & Aquaculture Science. 2006. Archived from the original on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- "Station: Isle of Portland". Met Office. 2021. Retrieved 30 December 2021.

- "UK 1971–2000 averages". Met Office. 2001. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 4 August 2007.

- "Days of Snow Lying Annual Average". Met Office. 2011. Archived from the original on 24 October 2018. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Mean Temperature (°C) Winter Average 1971–2000". Met Office. 2001. Archived from the original on 31 May 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

- "Growing season length – Annual average: 1971–2000". Met Office. 2012. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- "Hardiness Zone Map for Europe". GardenWeb. 1999. Archived from the original on 29 June 2007. Retrieved 20 June 2007.

- "Met Office: English climate". Met Office. 2005. Archived from the original on 17 November 2006. Retrieved 6 November 2006.

- Penn, Robert; Woodward, Antony (18 November 2007). "Bring me sunshine". London: Times Online. Archived from the original on 12 May 2008. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

- "2011 Census, Key Statistics for Local Authorities in England and Wales". Office for National Statistics. 2012. Archived from the original on 5 January 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2007.

- "Portland—Dorset For You". Dorset County Council. 2011. Archived from the original on 30 March 2016. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- "All releases of Labour Market Statistics". Office for National Statistics. 2012. Archived from the original on 18 May 2007. Retrieved 14 December 2012.

- "Route 26". Sustrans. Archived from the original on 21 August 2018. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- "Dorset Timetables". First Group. 2007. Archived from the original on 11 August 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- "Jurassic Coast Bus Service". Jurassic Coast. 2007. Archived from the original on 26 August 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- "used to go". BBC News. 2015. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- "St George's Community Primary School review". School Guide. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Welcome – Atlantic Academy Isle of Portland". Atlantic-aspirations.org. 10 April 2018. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "VIPs to attend handover of buildings to Portland Academy | Bournemouth Echo". Bournemouthecho.co.uk. 24 January 2013. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "About Us". Weymouth College. 2007. Archived from the original on 30 May 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- "Secondary Schools (A-Level) in Weymouth". Dorset Echo. 2006. Archived from the original on 30 October 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2008.

- "2012 Olympic Games sailing venue". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 2005. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- "Press Releases 2006". Weymouth & Portland National Sailing Academy. 2006. Archived from the original on 2 December 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- "Sailing town's joy at Olympic win". BBC. 6 July 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- "Dean and Reddyhoff Marina". Dean and Reddyhoff Limited. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 26 March 2007.

- "New Olympic marina plan approved". BBC. 27 June 2007. Archived from the original on 19 August 2007. Retrieved 27 June 2007.

- "2012 work completed at WPNSA". Royal Yachting Association. 2009. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- "Sailing rivals use Olympic venue". BBC News. 10 August 2009. Retrieved 10 August 2009.

- "First 2012 Olympic venue unveiled". BBC News. 28 November 2008. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 30 September 2009.

- Video of HM The Queen visiting the Sailing Academy at YouTube on YouTube

- "Watersports in Weymouth and Portland". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 2006. Archived from the original on 10 October 2006. Retrieved 12 November 2006.

- "World Rock Climbing Information: Portland". Rockfax. 2007. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 19 May 2007.

- South West Coast Path Association (2009). South West Coast Path 2009 Guide. SWCPA. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-907055-15-0.

- "Portland United FC". Portlandutdfc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Portland United Youth Football Club | Dorset FID". Familyinformationdirectory.dorsetforyou.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 16 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- "Wallace and Gromit spook island". BBC. 7 October 2005. Archived from the original on 13 April 2009. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- "Rabbits, the Portland taboo word". Weymouth & Portland Borough Council. 2006. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- Orel, H. (1990). Thomas Hardy's Personal Writings. Palgrave Macmillan UK. p. 263. ISBN 978-0-230-37371-6.

- "Thomas Hardy County and the Hardy Trail". Lyme Regis Tourist Information. 2007. Archived from the original on 23 March 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- "The Well-Beloved by Thomas Hardy". Full Books. 2007. Archived from the original on 7 June 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2007.

- "UK: The Gibraltar of Wessex". Telegraph. 14 July 2001. Archived from the original on 17 April 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- Connelly, Charlie (2011). Attention All Shipping: A Journey Round the Shipping Forecast. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-7481-3187-7.

- Meades, Jonathan (13 November 2012). Museum Without Walls. ISBN 9781908717191. Archived from the original on 19 October 2021. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- "The Isle of the Dead". British Society of Dowsers. 1999. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 30 July 2007.

- "Portland Sea Dragon". Roving Press. 2 July 2013. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- Davis, Joanna. "Page-turner is a family affair". Dorset Echo. Archived from the original on 13 February 2019. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- Fido Lunettes (nom de plume), 1825, An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Peninsula of Portland from the Earliest to the Present Time, p 48 summary in The Portland Year Book and Island Record 1905, reprinted Portland Museum, 2004. * Stuart Morris, 2016 Portland, an Illustrated History The Dovecote Press, Wimborne, Dorset: ISBN 978-0-9955462-0-2

- "The Independent Quarry Research Project". Portland Quarry and Sculpture Trust. 2000. Archived from the original on 2 February 2010. Retrieved 21 July 2010.

- "Length of the thermal growing season: 1772–2006". Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. 2005. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

- "Hardiness Zones – Details". United States National Arboretum. 2003. Archived from the original on 22 April 2001. Retrieved 22 December 2007.

Further reading

- Anon 1905, The Portland Year Book and Island Record 1905, reprinted 2004, Portland Museum, Portland, Dorset, 68 pages ASIN B005ZI3FCM

- Theresa Murphy, Murder in Dorset 1988. Robert Hale Limited, London – Portland chapters

- Stuart Morris, 2016 Portland, an Illustrated History The Dovecote Press, Wimborne, Dorset: ISBN 978-0-9955462-0-2

- Geoffrey Carter, 1999 Royal Navy at Portland Since 1845. Maritime Books, ISBN 978-0907771296.

- Stuart Morris, 1998 Portland (Discover Dorset Series) The Dovecote Press, Wimborne, Dorset: ISBN 1-874336-49-0.

- Rodney Legg, 1999 Portland Encyclopedia. Dorset Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0948699566.

- Jackson, Brian L. 1999. Isle of Portland railways. ISBN 0-85361-540-3

- Palmer, Susann. 1999. Ancient Portland: Archaeology of the Isle. Portland: S. Palmer. ISBN 0-9532811-0-8

- Stuart Morris, 2002 Portland: A Portrait in Colour The Dovecote Press, Wimborne, Dorset: ISBN 1-874336-91-1.

- Stuart Morris, 2006 Portland, Then and Now The Dovecote Press, Wimborne, Dorset: ISBN 1-904349-48-X.

- Dorset: The Royal Navy Stuart Morris, 2011, The Dovecote Press, Wimborne, Dorset: ISBN 978-1-904349-88-4. Features Portland.

- Weymouth & Portland, Stuart Morris 2012. The Dovecote Press, Wimborne, Dorset: ISBN 978-1-904349-98-3.

- Hackman, Gill (2014). Stone to Build London: Portland's Legacy. Monkton Farleigh, Wilts: Folly Books. ISBN 978-0-9564405-9-4. OCLC 910854593.

External links

- Map sources for grid reference SY 690 721.

- Portland's Tourism Website

- Portland Town Council

- . . 1914.

- Last Ferry Crossing