Sejm

The Sejm (English: /seɪm/ Seym, Polish: [sɛjm] (![]() listen)), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

listen)), officially known as the Sejm of the Republic of Poland (Polish: Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej), is the lower house of the bicameral parliament of Poland.

Sejm of the Republic of Poland Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej | |

|---|---|

| 9th term | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type | of the Polish parliament |

| History | |

| Founded | 1493 (historical) 1989 (contemporary) |

| Leadership | |

Marshal of the Sejm | |

Deputy Marshal of the Sejm | |

| Structure | |

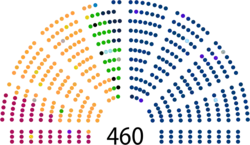

| Seats | 460 deputies (231 majority) |

| |

Political groups | Government (229)

Confidence and supply (4)

Opposition (228)

|

| Elections | |

Open-list proportional representation in 41 constituencies (5% national election thresholda) | |

Last election | 13 October 2019 |

Next election | 2023 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| The Sejm and Senate Complex, Warsaw | |

| Website | |

| sejm | |

| Footnotes | |

| a 8% for coalitions, 5% countywide not nationwide for ethnic minority electoral committees | |

The Sejm has been the highest governing body of the Third Polish Republic since the transition of government in 1989. Along with the upper house of parliament, the Senate, it forms the national legislature in Poland known as National Assembly (Polish: Zgromadzenie Narodowe). The Sejm is composed of 460 deputies (singular deputowany or poseł – "envoy") elected every four years by a universal ballot. The Sejm is presided over by a speaker called the "Marshal of the Sejm" (Marszałek Sejmu).

In the Kingdom of Poland, the term "Sejm" referred to an entire two-chamber parliament, comprising the Chamber of Deputies (Polish: Izba Poselska), the Senate and the King. It was thus a three-estate parliament. The 1573 Henrician Articles strengthened the assembly's jurisdiction, making Poland a constitutional elective monarchy. Since the Second Polish Republic (1918–1939), "Sejm" has only referred to the lower house of parliament.

History

Kingdom of Poland

Sejm (an ancient Proto-Lechitic word meaning "gathering" or "meeting") traces its roots to the King's Councils – wiece – which gained authority during the time of Poland's fragmentation (1146-1295). The 1180 Sejm in Łęczyca (known as the 'First Polish parliament') was the most notable, in that it established laws constraining the power of the ruler. It forbade arbitrary sequestration of supplies in the countryside and takeover of bishopric lands after the death of a bishop. These early Sejms only convened at the King's behest.

Following the 1493 Sejm in Piotrków, it became a regularly convening body, to which indirect elections were held every two years. The bicameral system was also established; the Sejm then comprised two chambers: the Senat (Senate) of 81 bishops and other dignitaries; and the Chamber of Deputies, made up of 54 envoys elected by smaller local sejmik (assemblies of landed nobility) in each of the Kingdom's provinces. At the time, Poland's nobility, which accounted for around 10% of the state's population (then the highest amount in Europe), was becoming particularly influential, and with the eventual development of the Golden Liberty, the Sejm's powers increased dramatically.[1]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

Over time, the envoys in the lower chamber grew in number and power as they pressed the king for more privileges. The Sejm eventually became even more active in supporting the goals of the privileged classes when the King ordered that the landed nobility and their estates (peasants) be drafted into military service.

Politics of Poland |

|---|

|

|

The Union of Lublin in 1569, united the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as one single state, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, and thus the Sejm was supplemented with new envoys from among the Lithuanian nobility. The Commonwealth ensured that the state of affairs surrounding the three-estates system continued, with the Sejm, Senate and King forming the estates and supreme deliberating body of the state. In the first few decades of the 16th century, the Senate had established its precedence over the Sejm; however, from the mid-1500s onwards, the Sejm became a very powerful representative body of the szlachta ("middle nobility"). Its chambers reserved the final decisions in legislation, taxation, budget, and treasury matters (including military funding), foreign policy, and the confirment of nobility.

The 1573 Warsaw Confederation saw the nobles of the Sejm officially sanction and guarantee religious tolerance in Commonwealth territory, ensuring a refuge for those fleeing the ongoing Reformation and Counter-Reformation wars in Europe.

Until the end of the 16th century, unanimity was not required, and the majority-voting process was the most commonly used system for voting. Later, with the rise of the Polish magnates and their increasing power, the unanimity principle was re-introduced with the institution of the nobility's right of liberum veto (Latin: "free veto"). Additionally, if the envoys were unable to reach a unanimous decision within six weeks (the time limit of a single session), deliberations were declared void and all previous acts passed by that Sejm were annulled. From the mid-17th century onward, any objection to a Sejm resolution, by either an envoy or a senator, automatically caused the rejection of other, previously approved resolutions. This was because all resolutions passed by a given session of the Sejm formed a whole resolution, and, as such, was published as the annual "constituent act" of the Sejm, e.g. the "Anno Domini 1667" act. In the 16th century, no single person or small group dared to hold up proceedings, but, from the second half of the 17th century, the liberum veto was used to virtually paralyze the Sejm, and brought the Commonwealth to the brink of collapse.

The liberum veto was abolished with the adoption of the Constitution of 3 May 1791, a piece of legislation which was passed as the "Government Act", and for which the Sejm required four years to propagate and adopt. The constitution's acceptance, and the possible long-term consequences it may have had, is arguably the reason for which the powers of Habsburg Austria, Russia and Prussia then decided to partition the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, thus putting an end to over 300 years of Polish parliamentary continuity. It is estimated that between 1493 and 1793, a Sejm was held 240 times, the total debate-time sum of which was 44 years.[1]

Partitions

After the fall of the Duchy of Warsaw, which existed as a Napoleonic client state between 1807 and 1815, and its short-lived Sejm of the Duchy of Warsaw, the Sejm of Congress Poland was established in Congress Poland of the Russian Empire; it was composed of the king (the Russian emperor), the upper house (Senate), and the lower house (Chamber of Deputies). Overall, during the period from 1795 until the re-establishment of Poland's sovereignty in 1918, little power was actually held by any Polish legislative body and the occupying powers of Russia, Prussia (later united Germany) and Austria propagated legislation for their own respective formerly-Polish territories at a national level.[1]

Tadeusz Rejtan tries to prevent the legalisation of the first partition of Poland by preventing the members of the Sejm from leaving the chamber (1773). Painting by Jan Matejko

Tadeusz Rejtan tries to prevent the legalisation of the first partition of Poland by preventing the members of the Sejm from leaving the chamber (1773). Painting by Jan Matejko

Congress Poland

The Chamber of Deputies, despite its name, consisted not only of 77 envoys (sent by local assemblies) from the hereditary nobility, but also of 51 deputies, elected by the non-noble population. All deputies were covered by Parliamentary immunity, with each individual serving for a term of office of six years, with third of the deputies being elected every two years. Candidates for deputy had to be able to read and write, and have a certain amount of wealth. The legal voting age was 21, except for those citizens serving in the military, the personnel of which were not allowed to vote. Parliamentary sessions were initially convened every two years, and lasted for (at least) 30 days. However, after many clashes between liberal deputies and conservative government officials, sessions were later called only four times (1818, 1820, 1826, and 1830, with the last two sessions being secret). The Sejm had the right to call for votes on civil and administrative legal issues, and, with permission from the king, it could also vote on matters related to the fiscal policy and the military. It had the right to exercise control over government officials, and to file petitions. The 64-member Senate on the other hand, was composed of voivodes and kasztelans (both types of provincial governors), Russian envoys, diplomats or princes, and nine bishops. It acted as the Parliamentary Court, had the right to control "citizens' books", and had similar legislative rights as did the Chamber of Deputies.[1]

Germany and Austria-Hungary

In the Free City of Cracow (1815–1846), a unicameral Assembly of Representatives was established, and from 1827, a unicameral provincial sejm existed in the Grand Duchy of Poznań. Poles were elected to and represented the majority in both of these legislatures; however, they were largely powerless institutions and exercised only very limited power. After numerous failures in securing legislative sovereignty in the early 19th century, many Poles simply gave up trying to attain a degree of independence from their foreign master-states. In the Austrian partition, a relatively powerless Sejm of the Estates operated until the time of the Spring of Nations. After this, in the mid to late 19th century, only in autonomous Galicia (1861–1914) was there a unicameral and functional National Sejm, the Sejm of the Land. It is recognised today as having played a major and overwhelming positive role in the development of Polish national institutions.

In the second half of the 19th century, Poles were able to become members of the parliaments of Austria, Prussia and Russia, where they formed Polish Clubs. Deputies of Polish nationality were elected to the Prussian Landtag from 1848, and then to the German Empire's Reichstag from 1871. Polish Deputies were members of the Austrian State Council (from 1867), and from 1906 were also elected to the Russian Imperial State Duma (lower chamber) and to the State Council (upper chamber).[1]

Second Polish Republic

After the First World War and re-establishment of Polish independence, the convocation of parliament, under the democratic electoral law of 1918, became an enduring symbol of the new state's wish to demonstrate and establish continuity with the 300-year Polish parliamentary traditions established before the time of the partitions. Maciej Rataj emphatically paid tribute to this with the phrase: "There is Poland there, and so is the Sejm".

During the interwar period of Poland's independence, the first Legislative Sejm of 1919, a Constituent Assembly, passed the Small Constitution of 1919, which introduced a parliamentary republic and proclaimed the principle of the Sejm's sovereignty. This was then strengthened, in 1921, by the March Constitution, one of the most democratic European constitutions enacted after the end of World War I. The constitution established a political system which was based on Montesquieu's doctrine of separation of powers, and which restored the bicameral Sejm consisting of a chamber of deputies (to which alone the name of "Sejm" was from then on applied) and the Senate. In 1919, Roza Pomerantz-Meltzer, a member of the Zionist party, became the first woman ever elected to the Sejm.[2][3]

The legal content of the March Constitution allowed for Sejm supremacy in the system of state institutions at the expense of the executive powers, thus creating a parliamentary republic out of the Polish state. An attempt to strengthen executive powers in 1926 (through the August Amendment) proved too limited and largely failed in helping avoid legislative grid-lock which had ensued as a result of too-great parliamentary power in a state which had numerous diametrically-opposed political parties sitting in its legislature. In 1935, the parliamentary republic was weakened further when, by way of, Józef Piłsudski's May Coup, the president was forced to sign the April Constitution of 1935, an act through which the head of state assumed the dominant position in legislating for the state and the Senate increased its power at the expense of the Sejm.

On 2 September 1939, the Sejm held its final pre-war session, during which it declared Poland's readiness to defend itself against invading German forces. On 2 November 1939, the President dissolved the Sejm and the Senate, which were then, according to plan, to resume their activity within two months after the end of the Second World War; this, however, never happened. During wartime, the National Council (1939–1945) was established to represent the legislature as part of the Polish Government in Exile. Meanwhile, in Nazi-occupied Poland, the Council of National Unity was set up; this body functioned from 1944 to 1945 as the parliament of the Polish Underground State. With the cessation of hostilities in 1945, and subsequent rise to power of the Communist-backed Provisional Government of National Unity, the Second Polish Republic legally ceased to exist.[1]

Stanisław Dubois speaking to envoys and diplomats in the Sejm, 1931

Stanisław Dubois speaking to envoys and diplomats in the Sejm, 1931 Józef Beck, Minister of Foreign Affairs, delivers his famous Honour Speech in the Sejm, 5 May 1939.

Józef Beck, Minister of Foreign Affairs, delivers his famous Honour Speech in the Sejm, 5 May 1939.

Polish People's Republic

The Sejm in the Polish People's Republic had 460 deputies throughout most of its history. At first, this number was declared to represent one deputy per 60,000 citizens (425 were elected in 1952), but, in 1960, as the population grew, the declaration was changed: The constitution then stated that the deputies were representative of the people and could be recalled by the people, but this article was never used, and, instead of the "five-point electoral law", a non-proportional, "four-point" version was used. Legislation was passed with majority voting.

Under the 1952 Constitution, the Sejm was defined as "the highest organ of State authority" in Poland, as well as "the highest spokesman of the will of the people in town and country." On paper, it was vested with great lawmaking and oversight powers. For instance, it was empowered with control over "the functioning of other organs of State authority and administration," and ministers were required to answer questions posed by deputies within seven days.[4] In practice, it did little more than rubber-stamp decisions already made by the Communist Polish United Workers Party and its executive bodies.[5] This was standard practice in nearly all Communist regimes due to the principle of democratic centralism.

The Sejm voted on the budget and on the periodic national plans that were a fixture of communist economies. The Sejm deliberated in sessions that were ordered to convene by the State Council.

The Sejm also chose a Prezydium ("presiding body") from among its members. The Prezydium was headed by the speaker, or Marshal, who was always a member of the United People's Party. In its preliminary session, the Sejm also nominated the Prime Minister, the Council of Ministers of Poland, and members of the State Council. It also chose many other government officials, including the head of the Supreme Chamber of Control and members of the State Tribunal and the Constitutional Tribunal, as well as the Ombudsman (the last three bodies of which were created in the 1980s).

When the Sejm was not in session, the State Council had the power to issue decrees that had the force of law. However, those decrees had to be approved by the Sejm at its next session.[4] In practice, the principles of democratic centralism meant that such approval was only a formality.

The Senate was abolished by the referendum in 1946, after which the Sejm became the sole legislative body in Poland.[1] Even though the Sejm was largely subservient to the Communist party, one deputy, Romuald Bukowski (an independent) voted against the imposition of martial law in 1982.[6]

Third Polish Republic

After the end of communism in 1989, the Senate was reinstated as the second house of a bicameral national assembly, while the Sejm remained the first house. The Sejm is now composed of 460 deputies elected by proportional representation every four years.

Between 7 and 19 deputies are elected from each constituency using the d'Hondt method (with one exception, in 2001, when the Sainte-Laguë method was used), their number being proportional to their constituency's population. Additionally, a threshold is used, so that candidates are chosen only from parties that gained at least 5% of the nationwide vote (candidates from ethnic-minority parties are exempt from this threshold).[1]

The Sejm building in Warsaw

The Sejm building in Warsaw The Sejm's main hall

The Sejm's main hall Sessions chamber in the Sejm

Sessions chamber in the Sejm Sessions chamber viewed from the rostrum

Sessions chamber viewed from the rostrum Sejm cross

Sejm cross Column hall in the Sejm

Column hall in the Sejm

Historical composition of the Sejm

Second Republic (1918-1939)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1919 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1922 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1928 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1930 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1935 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1938 |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

PRL (1945-1989)

| ||||||||||||||||

| 1947 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1952 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1957 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1961 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1965 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1969 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1972 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1976 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1980 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1985 |

| |||||||||||||||

| 1989 |

| |||||||||||||||

Third republic (since 1989)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1991 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1993 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1997 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2001 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2005 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2007 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2011 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2019 |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

Standing committees

- Administration and Internal Affairs

- Agriculture and Rural Development

- Liaison with Poles Abroad

- Constitutional Accountability

- Culture and Media

- Deputies' Ethics

- Economic Committee

- Education, Science and Youth

- Enterprise Development

- Environment Protection, Natural Resources and Forestry

- European Union Affairs

- Family and Women Rights

- Foreign Affairs

- Health

- Infrastructure

- Justice and Human Rights

- Legislative

- Local Self-Government and Regional Policy

- National and Ethnic Minorities

- National Defence

- Physical Education and Sport

- Public Finances

- Rules and Deputies' Affairs

- Social Policy

- Special Services

- State Control

- State Treasury

- Work

Current standings

| Affiliation | Deputies (Sejm) | Senators | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Results of the 2019 election | As of 22 June 2022 |

Change | Results of the 2019 election | As of 22 June 2022 |

Change | ||

| Parliamentary clubs | |||||||

| Law and Justice | 235 | 228 | 48 | 46 | |||

| Civic Coalition | 134 | 126 | 43 | 41 | |||

| The Left | 49 | 44 | 2 | 0 | |||

| Polish Coalition | 30 | 24 | 3 | 0 | |||

| Deputies' groups | |||||||

| Confederation | 11 | 11 | — | — | |||

| Poland 2050 | — | 8 | — | 1 | |||

| Agreement | — | 5 | — | 1 | |||

| Kukiz'15 | — | 4 | — | — | |||

| Polish Affairs | — | 3 | — | — | |||

| Polish Socialist Party | — | 3 | — | 2 | |||

| Senators' groups | |||||||

| Ind. Senators Group | — | — | — | 3 | |||

| Polish Coalition in the Senate | — | — | — | 4 | |||

| Non-inscrits/Independents | |||||||

| Independents | — | 4 | 4 | 2 | |||

| Total members | 460 | 460 | 100 | 100 | |||

| Vacant | — | 0 | — | 0 | |||

| Total Seats | 460 | 100 | |||||

See also

- Electoral districts of Poland (1935–39)

- Polish constitutional crisis, 2015

Types of sejm

- Confederated sejm (Sejm skonfederowany)

- Convocation sejm (Sejm konwokacyjny)

- Coronation sejm (Sejm koronacyjny)

- Election sejm (Sejm elekcyjny)

- National Assembly of the Republic of Poland (Zgromadzenie Narodowe)

- Sejmik

- Voivodship sejmik (Sejmik wojewódzki)

Notable sejms

- Silent Sejm (Sejm Niemy 1717)

- Convocation Sejm (1764) (Sejm konwokacyjny)

- Repnin Sejm (Sejm Repninowski 1767–1768)

- Partition Sejm (Sejm rozbiorowy 1773–1776)

- Great Sejm (Sejm Wielki 1788–1792)

- Grodno Sejm (Sejm grodzieński 1791)

- Silesian Sejm (Sejm Śląski 1920–1939)

- Contract Sejm (Sejm Kontraktowy 1989)

Notes

- Anna Dąbrowska-Banaszek, Andrzej Gut-Mostowy, Wojciech Murdzek, Marcin Ociepa, Grzegorz Piechowiak

- Jadwiga Emilewicz, Monika Pawłowska

- Agnieszka Ścigaj

- Andrzej Sośnierz, Zbigniew Girzyński

- Łukasz Mejza

- Zbigniew Ajchler

- Former Democratic Left Alliance and Spring MPs

- Radosław Lubczyk, Ireneusz Raś, Jacek Tomczak

- Jacek Protasiewicz

- Robert Winnicki, Krzysztof Bosak, Krzysztof Tuduj, Krystian Kamiński, Michał Urbaniak

- Jakub Kulesza, Artur Dziambor, Dobromir Sośnierz

- Janusz Korwin-Mikke, Konrad Berkowicz

- Grzegorz Braun

- Hanna Gill-Piątek, Michał Gramatyka, Paulina Hennig-Kloska, Wojciech Maksymowicz, Joanna Mucha, Mirosław Suchoń, Paweł Zalewski, Tomasz Zimoch

- Paweł Kukiz, Jarosław Sachajko, Stanisław Tyszka, Stanisław Żuk

- Andrzej Rozenek, Joanna Senyszyn

- Robert Kwiatkowski

- Ryszard Galla

- Paweł Szramka

References

- "Poznaj Sejm". opis.sejm.gov.pl. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- Davies, Norman (1982). God's Playground: A History of Poland. Columbia University Press. p. 302.

- Strauss, Herbert Arthur (1993). Hostages of Modernization: Studies on Modern Antisemitism, 1870-1933/39. Walter de Gruyter. p. 985.

- Chapter 3 of 1952 Constitution

- Poland: a country study. Library of Congress Federal Research Division, December 1989.

- The Associated Press (22 October 1992). "Romuald Bukowski; Polish Legislator, 64". The New York Times.