Pruning

Pruning is a horticultural, arboricultural, and silvicultural practice involving the selective removal of certain parts of a plant, such as branches, buds, or roots.

The practice entails the targeted removal of diseased, damaged, dead, non-productive, structurally unsound, or otherwise unwanted plant material from crop and landscape plants. Some try to remember the categories as "the 4 D's": the last general category being "deranged".[1] In general, the smaller the branch that is cut, the easier it is for a woody plant to compartmentalize the wound and thus limit the potential for pathogen intrusion and decay. It is therefore preferable to make any necessary formative structural pruning cuts to young plants, rather than removing large, poorly placed branches from mature plants.

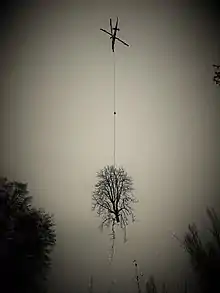

In nature, meteorological conditions such as wind, ice and snow, and salinity can cause plants to self-prune. This natural shedding is called abscission.

Specialized pruning practices may be applied to certain plants, such as roses, fruit trees, and grapevines. It is important when pruning that the tree's limbs are kept intact, as this is what helps the tree stay upright.[2] Different pruning techniques may be deployed on herbaceous plants than those used on perennial woody plants. Hedges, by design, are usually (but not exclusively) maintained by hedge trimming, rather than by pruning.

Reasons to prune plants include deadwood removal, shaping (by controlling or redirecting growth), improving or sustaining health, reducing risk from falling branches, preparing nursery specimens for transplanting, and both harvesting and increasing the yield or quality of flowers and fruits.

Pruning landscape and amenity trees

Types of branch union

For arboricultural purposes the unions of tree branches (i.e. where they join together) are placed in one of three categories: collared, collarless or codominant. Regardless of the overall type of pruning being carried out, each type of union is cut in a particular way so that the branch has less chance of regrowth from the cut area and the best chance of sealing over and compartmentalising decay. This is often referred to by arborists as "target cutting".

Deadwooding

Branches die off for a number of reasons including sunlight deficiency, pest and disease damage, and root structure damage. A dead branch will at some point decay back to the parent stem and fall off. This is normally a slow process but can be hastened by high winds or extreme temperatures. The main reason deadwooding is performed is safety. Situations that usually demand removal of deadwood include trees that overhang public roads, houses, public areas, power lines, telephone cables and gardens. Trees located in wooded areas are usually assessed as lower risk but assessments consider the number of visitors. Trees adjacent to footpaths and access roads are often considered for deadwood removal.[3]

Another reason for deadwooding is amenity value, i.e. a tree with a large amount of deadwood throughout the crown will look more aesthetically pleasing with the deadwood removed. The physical practice of deadwooding can be carried out most of the year though should be avoied when the tree is coming into leaf. The deadwooding process speeds up the tree's natural abscission process. It also reduces unwanted weight and wind resistance and can help overall balance.

Crown and canopy thinning

Crown and canopy thinning increases light and reduces wind resistance by selective removal of branches throughout the canopy of the tree.[4]

Crown canopy lifting

Crown lifting involves the removal of the lower branches to a given height. The height is achieved by the removal of whole branches or removing the parts of branches which extend below the desired height. The branches are normally not lifted to more than one third of the tree's total height.

Crown lifting is done for access; these being pedestrian, vehicle or space for buildings and street furniture. Lifting the crown will allow traffic and pedestrians to pass underneath safely. This pruning technique is usually used in the urban environment as it is for public safety and aesthetics rather than tree form and timber value.

Crown lifting introduces light to the lower part of the trunk; this, in some species can encourage epicormic growth from dormant buds. To reduce this sometimes smaller branches are left on the lower part of the trunk. Excessive removal of the lower branches can displace the canopy weight, this will make the tree top heavy, therefore adding stress to the tree. When a branch is removed from the trunk, it creates a large wound. This wound is susceptible to disease and decay, and could lead to reduced trunk stability. Therefore, much time and consideration must be taken when choosing the height the crown is to be lifted to.

This would be an inappropriate operation if the tree species’ form was of a shrubby nature. This would therefore remove most of the foliage and would also largely unbalance the tree. This procedure should not be carried out if the tree is in decline, poor health or dead, dying or dangerous (DDD) as the operation will remove some of the photosynthetic area the tree uses. This will increase the decline rate of the tree and could lead to death.

If the tree is of great importance to an area or town, (i.e. veteran or ancient) then an alternative solution to crown lifting would be to move the target or object so it is not in range. For example, diverting a footpath around a tree's drip line so the crown lift is not needed. Another solution would be to prop up or cable-brace the low hanging branch. This is a non-invasive solution which in some situations may be more economical and environmentally friendly.

Directional or formative pruning

Removal of appropriate branches to make the tree structurally sound while shaping it.

Vista pruning

Selectively pruning a window of view in a tree.

Crown reduction

Reducing the height and or spread of a tree by selectively cutting back to smaller branches and in fruit trees for increasing of light interception and enhancing fruit quality.

Pollarding

A regular form of pruning where certain deciduous species are pruned back to pollard heads every year in the dormant period. This practice is usually commenced on juvenile trees so they can adapt to the harshness of the practice.

Types

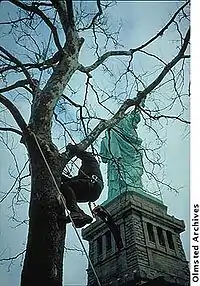

Arborists, orchardists, and gardeners use various garden tools and tree cutting tools designed for the purpose, such as hand pruners, loppers, or chainsaws.[5] Additionally in forestry, bush saws are commonly used and these are often attached to poles that reach up to 5-6 m, this is a more efficient way of pruning than with ladders. These bush saws on polls have also been motorized as chainsaws which is even more efficient. Older technology used Billhooks, Kaiser blades and pruning knives. Although still used in some coppicing they are not used so much in commercial forestry due to the difficulty of cutting flush with the stem. Flush cuts lead to good wood, non-flush or bark damaging cuts (which are more likely with a swung blade than a sawed one) put the tree at risk of entry cords from forest pathogens.

Regardless of the various names used for types of pruning, there are only two basic cuts: One cuts back to an intermediate point, called heading back cut, and the other cuts back to some point of origin, called thinning out cut.[6]

Removing a portion of a growing stem down to a set of desirable buds or side-branching stems. This is commonly performed in well trained plants for a variety of reasons, for example to stimulate growth of flowers, fruit or branches, as a preventive measure to wind and snow damage on long stems and branches, and finally to encourage growth of the stems in a desirable direction. Also commonly known as heading-back.

- Thinning: A more drastic form of pruning, a thinning out cut is the removal of an entire shoot, limb, or branch at its point of origin.[6] This is usually employed to revitalize a plant by removing over-mature, weak, problematic, and excessive growths. When performed correctly, thinning encourages the formation of new growth that will more readily bear fruit and flowers. This is a common technique in pruning roses and for amplifying and "opening-up" the branching of neglected trees, or for renewing shrubs with multiple branches.

- Topping: Topping is a very severe form of pruning which involves removing all branches and growths down to a few large branches or to the trunk of the tree. When performed correctly it is used on very young trees, and can be used to begin training younger trees for pollarding or for trellising to form an espalier.

- Raising removes the lower branches from a tree in order to provide clearance for buildings, vehicles, pedestrians, and vistas.

- Reduction reduces the size of a tree, often for clearance for utility lines. Reducing the height or spread of a tree is best accomplished by pruning back the leaders and branch terminals to lateral branches that are large enough to assume the terminal roles (at least one-third the diameter of the cut stem). Compared to topping, reduction helps maintain the form and structural integrity of the tree.[7]

In orchards, fruit trees are often lopped to encourage regrowth and to maintain a smaller tree for ease of picking fruit. The pruning regime in orchards is more planned and the productivity of each tree is an important factor.

Deadheading is the act of removing spent flowers or flowerheads for aesthetics, to prolong bloom for up to several weeks or promote rebloom, or to prevent seeding.

Time period

In general, pruning dead wood and small branches can be done at any time of year. Depending on the species, many temperate plants can be pruned either during dormancy in winter, or, for species where winter frost can harm a recently pruned plant, after flowering is completed. In the temperate areas of the northern hemisphere autumn pruning should be avoided, as the spores of disease and decay fungi are abundant at this time of year.

Some woody plants tend to bleed profusely from cuts, such as mesquite and maple. Some callus over slowly, such as magnolia. In this case, they are better pruned during active growth when they can more readily heal. Woody plants that flower early in the season, on spurs that form on wood that has matured the year before, such as apples, should be pruned right after flowering as later pruning will sacrifice flowers the following season. Forsythia, azaleas and lilacs all fall into this category.

See also

- Arborist

- Branch collar

- Chainsaw safety clothing

- Cladoptosis or natural regular branch shedding

- Coppicing

- Dead hedge (which can be made from pruned branches to attract insects for hibernation and pollination)

- Fruit tree forms

- Fruit tree pruning

- Ice pruning

- Pollarding

- Professional Landcare Network (PLANET)

- Ramification (botany)

- Salt pruning

- Self or natural pruning: Plant senescence#Plant self-pruning and Fire adaptations#Self-pruning branches

- Thinning

- Topiary

- Tree fork

- Tree topping

References

- "The 4 D's: Dead, Diseased, Damaged, or Deranged! – TreePeople". www.treepeople.org. Retrieved 2021-04-08.

- "Pruning - Nelson's Tree Services". Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Removal of dead wood - Nelson's Tree Services". Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Crown Reduction - Nelson's Tree Services". Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- Encyclopedia of gardening (3rd U.S., rev. and updated ed.). London: DK Pub. 2012. pp. 554–556. ISBN 9780756698287.

- "Tree Fruit Production Guide". tfpg.cas.psu.edu. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

- "Houston Tree Care and Tree Cutting Tips". www.bigdtreeservice.com. Archived from the original on 22 December 2017. Retrieved 20 December 2017.

Bibliography

- Sunset Editors, (1995) Western Garden Book, Sunset Books Inc, ISBN 978-0-376-03851-7

- James, N. D. G, The arboriculturalist's companion, second edition 1990, Blackwell Publishers Ltd, Great Britain.

- Shigo, A, 1991, Modern arboriculture, third printing, Durham, New Hampshire, USA, Shirwin Dodge Printers.

- Shigo, A, 1989, A New Tree Biology. Shigo & trees Associates.

- J.M. Dunn, C.J. Atkinson, N.A. Hipps, 2002, Effects of two different canopy manipulations on leaf water use and photosynthesis as determined by gas exchange and stable isotope discrimination, East Malling, University of Cambridge.

- Shigo. A. L, 1998, Modern Arboriculture, third printing (2003), USA, Sherwin Dodge Printers

- British standards 3998:1989, Recommendations for Tree Work.

- Lonsdale. D, 1999, Principles of tree hazard assessment and management, 6th impression 2008, forestry commission, Great Britain.