Red-billed chough

The red-billed chough, Cornish chough or simply chough (/ˈtʃʌf/ CHUF; Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax), is a bird in the crow family, one of only two species in the genus Pyrrhocorax. Its eight subspecies breed on mountains and coastal cliffs from the western coasts of Ireland and Britain east through southern Europe and North Africa to Central Asia, India and China.

| Red-billed chough | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult of subspecies P. p. barbarus on La Palma, Canary Islands | |

| |

| Adult P. p. himalayanus in Sikkim, India | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Corvidae |

| Genus: | Pyrrhocorax |

| Species: | P. pyrrhocorax |

| Binomial name | |

| Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax | |

| |

| Approximate distribution shown in green | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

This bird has glossy black plumage, a long curved red bill, red legs, and a loud, ringing call. It has a buoyant acrobatic flight with widely spread primaries. The red-billed chough pairs for life and displays fidelity to its breeding site, which is usually a cave or crevice in a cliff face. It builds a wool-lined stick nest and lays three eggs. It feeds, often in flocks, on short grazed grassland, taking mainly invertebrate prey.

Although it is subject to predation and parasitism, the main threat to this species is changes in agricultural practices, which have led to population decline, some local extirpation, and range fragmentation in Europe; however, it is not threatened globally. The red-billed chough, which derived its common name from the jackdaw, was formerly associated with fire-raising, and has links with Saint Thomas Becket and Cornwall. The red-billed chough has been depicted on postage stamps of a few countries, including the Isle of Man, with four different stamps, and the Gambia, where the bird does not occur.

Taxonomy

The red-billed chough was first described by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 10th edition of Systema Naturae as Upupa pyrrhocorax.[2] It was moved to its current genus, Pyrrhocorax, by Marmaduke Tunstall in his 1771 Ornithologia Britannica.[3] The genus name is derived from Greek πυρρός (pyrrhos), "flame-coloured", and κόραξ (korax), "raven".[4] The only other member of the genus is the Alpine chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus.[5] The closest relatives of the choughs are the typical crows, Corvus, especially the jackdaws in the subgenus Coloeus.[6]

"Chough" was originally an alternative onomatopoeic name for the jackdaw, Corvus monedula, based on its call. The similar red-billed species, formerly particularly common in Cornwall, became known initially as "Cornish chough" and then just "chough", the name transferring from one species to the other.[7] The Australian white-winged chough, Corcorax melanorhamphos, despite its similar shape and habits, is only distantly related to the true choughs, and is an example of convergent evolution.[8]

Subspecies

There are eight extant subspecies, although differences between them are slight.[9]

- P. p. pyrrhocorax, the nominate subspecies and smallest form, is endemic to the British Isles, where it is restricted to Ireland, the Isle of Man, and the far west of Wales and Scotland,[9] although it recolonised Cornwall in 2001 after an absence of 50 years.[10]

- P. p. erythropthalmus, described by Louis Jean Pierre Vieillot in 1817 as Coracia erythrorhamphos,[11] occurs in the red-billed chough's continental European range, excluding Greece. It is larger and slightly greener than the nominate race.[9]

- P. p. barbarus, described by Charles Vaurie under its current name in 1954, is resident in North Africa and on La Palma in the Canary Islands. Compared to P. p. erythropthalmus, it is larger, has a longer tail and wings, and its plumage has a greener gloss. It is the longest-billed form, both absolutely and relatively.[12]

- P. p. baileyi described by Austin Loomer Rand and Charles Vaurie under its current name in 1955,[13] is a dull-plumaged subspecies endemic to Ethiopia, where it occurs in two separate areas. The two populations could possibly represent different subspecies.[9]

- P. p. docilis, described by Johann Friedrich Gmelin as Corvus docilis in 1774,[14] breeds from Greece to Afghanistan. It is larger than the African subspecies, but it has a smaller bill and its plumage is very green-tinted, with little gloss.[9]

- P. p. himalayanus, described by John Gould in 1862 as Fregilus himalayanus,[15] is found from the Himalayas to western China, but intergrades with P. p. docilis in the west of its range. It is the largest subspecies, long-tailed, and with blue or purple-blue glossed feathers.[9]

- P. p. centralis, described by Erwin Stresemann in 1928 under its current name,[16] breeds in Central Asia. It is smaller and less strongly blue than P. p. himalayanus,[9] but its distinctness from the next subspecies has been questioned.[12]

- P. p. brachypus, described by Robert Swinhoe in 1871 as Fregilus graculus var. brachypus,[17] breeds in central and northern China, Mongolia and southern Siberia. It is similar to P. p. centralis but with a weaker bill.[9]

There is one known prehistoric form of the red-billed chough. P. p. primigenius, a subspecies that lived in Europe during the last ice age, which was described in 1875 by Alphonse Milne-Edwards from finds in southwest France.[18][19]

Detailed analysis of call similarity suggests that the Asiatic and Ethiopian races diverged from the western subspecies early in evolutionary history, and that Italian red-billed choughs are more closely allied to the North African subspecies than to those of the rest of Europe.[20]

Description

The adult of the "nominate" subspecies of the red-billed chough, P. p. pyrrhocorax, is 39–40 centimetres (15–16 inches) in length, has a 73–90 centimetres (29–35 inches) wingspan,[21] and weighs an average 310 grammes (10.9 oz).[4] Its plumage is velvet-black, green-glossed on the body, and it has a long curved red bill and red legs. The sexes are similar (although adults can be sexed in the hand using a formula involving tarsus length and bill width)[22] but the juvenile has an orange bill and pink legs until its first autumn, and less glossy plumage.[9]

The red-billed chough is unlikely to be confused with any other species of bird. Although the jackdaw and Alpine chough share its range, the jackdaw is smaller and has unglossed grey plumage, and the Alpine chough has a short yellow bill. Even in flight, the two choughs can be distinguished by Alpine's less rectangular wings, and longer, less square-ended tail.[9]

The red-billed chough's loud, ringing chee-ow call is clearer and louder than the similar vocalisation of the jackdaw, and always very different from that of its yellow-billed congener, which has rippling preep and whistled sweeeooo calls.[9] Small subspecies of the red-billed chough have higher frequency calls than larger races, as predicted by the inverse relationship between body size and frequency.[23]

Distribution and habitat

.jpg.webp)

The red-billed chough breeds in Ireland, western Great Britain, the Isle of Man, southern Europe and the Mediterranean basin, the Alps, and in mountainous country across Central Asia, India and China, with two separate populations in the Ethiopian Highlands. It is a non-migratory resident throughout its range.[9]

Its main habitat is high mountains; it is found between 2,000 and 2,500 metres (6,600 and 8,200 ft) in North Africa, and mainly between 2,400 and 3,000 metres (7,900 and 9,800 ft) in the Himalayas. In that mountain range it reaches 6,000 metres (20,000 feet) in the summer, and has been recorded at 7,950 metres (26,080 feet) altitude on Mount Everest.[9] In the British Isles and Brittany it also breeds on coastal sea cliffs, feeding on adjacent short grazed grassland or machair. It was formerly more widespread on coasts but has suffered from the loss of its specialised habitat.[24][25] It tends to breed at a lower elevation than the Alpine chough,[21] that species having a diet better adapted to high altitudes.[26]

Behaviour and ecology

Breeding

The red-billed chough breeds from three years of age, and normally raises only one brood a year,[4] although the age at first breeding is greater in large populations.[27] A pair exhibits strong mate and site fidelity once a bond is established.[28] The bulky nest is composed of roots and stems of heather, furze or other plants, and is lined with wool or hair;[21] in central Asia, the hair may be taken from live Himalayan tahr. The nest is constructed in a cave or similar fissure in a crag or cliff face.[21] In soft sandstone, the birds themselves excavate holes nearly a metre deep.[29] Old buildings may be used, and in Tibet working monasteries provide sites, as occasionally do modern buildings in Mongolian towns, including Ulaanbaatar.[9] The red-billed chough will utilise other artificial sites, such as quarries and mineshafts for nesting where they are available.[30]

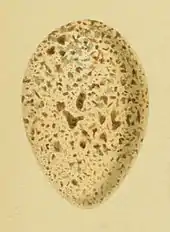

The chough lays three to five eggs 3.9 by 2.8 centimetres (1.5 by 1.1 inches) in size and weighing 15.7 grammes (0.55 oz), of which 6% is shell.[4] They are spotted, not always densely, in various shades of brown and grey on a creamy or slightly tinted ground.[21]

The egg size is independent of the clutch size and the nest site, but may vary between different females.[31] The female incubates for 17–18 days before the altricial downy chicks are hatched, and is fed at the nest by the male. The female broods the newly hatched chicks for around ten days,[32] and then both parents share feeding and nest sanitation duties. The chicks fledge 31–41 days after hatching.[4]

Juveniles have a 43% chance of surviving their first year, and the annual survival rate of adults is about 80%. Choughs generally have a lifespan of about seven years,[4] although an age of 17 years has been recorded.[28] The temperature and rainfall in the months preceding breeding correlates with the number of young fledging each year and their survival rate. Chicks fledging under good conditions are more likely to survive to breeding age, and have longer breeding lives than those fledging under poor conditions.[27]

Feeding

The red-billed chough's food consists largely of insects, spiders and other invertebrates taken from the ground, with ants probably being the most significant item.[9] The Central Asian subspecies P. p. centralis will perch on the backs of wild or domesticated mammals to feed on parasites. Although invertebrates make up most of the chough's diet, it will eat vegetable matter including fallen grain, and in the Himalayas has been reported as damaging barley crops by breaking off the ripening heads to extract the corn.[9] In the Himalayas, they form large flocks in winter.[33]

The preferred feeding habitat is short grass produced by grazing, for example by sheep and rabbits, the numbers of which are linked to the chough's breeding success. Suitable feeding areas can also arise where plant growth is hindered by exposure to coastal salt spray or poor soils.[34][35] It will use its long curved bill to pick ants, dung beetles and emerging flies off the surface, or to dig for grubs and other invertebrates. The typical excavation depth of 2–3 cm (3⁄4–1+1⁄4 in) reflects the thin soils which it feeds on, and the depths at which many invertebrates occur, but it may dig to 10–20 cm (4–8 in) in appropriate conditions.[36][37]

Where the two chough species occur together, there is only limited competition for food. An Italian study showed that the vegetable part of the winter diet for the red-billed chough was almost exclusively Gagea bulbs, whilst the Alpine chough took berries and hips. In June, red-billed choughs fed on Lepidoptera larvae whereas Alpine choughs ate cranefly pupae. Later in the summer, the Alpine chough mainly consumed grasshoppers, whilst the red-billed chough added cranefly pupae, fly larvae and beetles to its diet.[26] Both choughs will hide food in cracks and fissures, concealing the cache with a few pebbles.[38]

Natural threats

The red-billed chough's predators include the peregrine falcon, golden eagle and Eurasian eagle-owl, while the common raven will take nestlings.[39][40][41][42] In northern Spain, red-billed choughs preferentially nest near lesser kestrel colonies. This small insectivorous falcon is better at detecting a predator and more vigorous in defence than its corvid neighbours. The breeding success of the red-billed chough in the vicinity of the kestrels was found to be much higher than that of birds elsewhere, with a lower percentage of nest failures (16% near the falcon, 65% elsewhere).[42]

This species is occasionally parasitised by the great spotted cuckoo, a brood parasite for which the Eurasian magpie is the primary host.[43] Red-billed choughs can acquire blood parasites such as Plasmodium, but a study in Spain showed that the prevalence was less than one percent, and unlikely to affect the life history and conservation of this species.[44] These low levels of parasitism contrast with a much higher prevalence in some other passerine groups; for example a study of thrushes in Russia showed that all the fieldfares, redwings and song thrushes sampled carried haematozoans, particularly Haemoproteus and Trypanosoma.[45]

Red-billed choughs can also carry mites, but a study of the feather mite Gabucinia delibata, acquired by young birds a few months after fledging when they join communal roosts, suggested that this parasite actually improved the body condition of its host. It is possible that the feather mites enhance feather cleaning and deter pathogens,[46] and may complement other feather care measures such as sunbathing, and anting—rubbing the plumage with ants (the formic acid from the insects deters parasites).[9]

Status

The red-billed chough has an extensive range, estimated at ten million square kilometres (four million square miles), and a large population, including an estimated 86,000 to 210,000 individuals in Europe. Over its range as a whole, the species is not believed to approach the thresholds for the global population decline criterion of the IUCN Red List (i.e., declining more than 30% in ten years or three generations), and is therefore evaluated as least concern.[1]

However, the European range has declined and fragmented due to the loss of traditional pastoral farming, persecution and perhaps disturbance at breeding and nesting sites, although the numbers in France, Great Britain and Ireland may now have stabilised.[21] The European breeding population is between 12,265 and 17,370 pairs, but only in Spain is the species still widespread. Since in the rest of the continent breeding areas are fragmented and isolated, the red-billed chough has been categorised as "vulnerable" in Europe.[30]

In Spain the red-billed chough has recently expanded its range by utilising old buildings, with 1,175 breeding pairs in a 9,716-square-kilometre (3,751 sq mi) study area. These new breeding areas usually surround the original montane core areas. However, the populations with nest sites on buildings are threatened by human disturbance, persecution and the loss of old buildings.[47] Fossils of both chough species were found in the mountains of the Canary Islands. The local extinction of the Alpine chough and the reduced range of red-billed chough in the islands may have been due to climate change or human activity.[48]

A small group of wild red-billed chough arrived naturally in Cornwall in 2001, and nested in the following year. This was the first English breeding record since 1947, and a slowly expanding population has bred every subsequent year.[25]

In Jersey, the Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust, in partnership with the States of Jersey and the National Trust for Jersey began a project in 2010, aimed at restoring selected areas of Jersey's coastline with the intention of returning those birds that had become locally extinct. The red-billed chough was chosen as a flagship species for this project, having been absent from Jersey since around 1900. Durrell initially received two pairs of choughs from Paradise Park in Cornwall and began a captive breeding programme.[49] In 2013, juveniles were released onto the north coast of Jersey using soft-release methods developed at Durrell. Over the next five years, small cohorts of captive-bred choughs were released, monitored, and provided supplemental food.[50]

In culture

Greek mythology

In Greek mythology, the red-billed chough, also known as 'sea-crow', was considered sacred to the Titan Cronus and dwelt on Ogygia, Calypso's 'Blessed Island',[51] where "The birds of broadest wing their mansions form/The chough, the sea-mew, the loquacious crow."[52]

Nuisance species

Up to the eighteenth century, the red-billed chough was associated with fire-raising, and was described by William Camden as incendaria avis, "oftentime it secretly conveieth fire sticks, setting their houses afire".[7] Daniel Defoe was also familiar with this story:

It is counted little better than a kite, for it is of ravenous quality, and is very mischievous; it will steal and carry away any thing it finds about the house, that is not too heavy, tho' not fit for its food; as knives, forks, spoons and linnen cloths, or whatever it can fly away with, sometimes they say it has stolen bits of firebrands, or lighted candles, and lodged them in the stacks of corn, and the thatch of barns and houses, and set them on fire; but this I only had by oral tradition.[53]

Not all mentions of "chough" refer to this species. Because of the origins of its name, when Shakespeare writes of "the crows and choughs that wing the midway air" [King Lear, act 4, scene 6] or Henry VIII's Vermin Act of 1532 is "ordeyned to dystroye Choughes, Crowes and Rookes", they are clearly referring to the jackdaw.[7]

Cornish heraldry

The red-billed chough has a long association with Cornwall, and appears on the Cornish coat of arms.[10] According to Cornish legend King Arthur did not die after his last battle but rather his soul migrated into the body of a red-billed chough, the red colour of its bill and legs being derived from the blood of the last battle[54] and hence killing this bird was unlucky.[51] Legend also holds that after the last Cornish chough departs from Cornwall, then the return of the chough, as happened in 2001, will mark the return of King Arthur.[55]

In English heraldry the bird is always blazoned as "a Cornish chough" and is usually shown "proper", with tinctures as in nature. Since the 14th century, St Thomas Becket (d.1170), Archbishop of Canterbury, has retrospectively acquired an attributed coat of arms consisting of three Cornish choughs on a white field,[56] although as he died 30 to 45 years before the start of the age of heraldry,[57] in reality he bore no arms. These attributed arms appear in many English churches dedicated to him. The symbolism behind the association is not known for certain. According to one legend, a chough strayed into Canterbury Cathedral during Becket's murder, while another suggests that the choughs are a canting reference to Becket's name, as they were once known as "beckits".[58] However the latter theory does not stand up to scrutiny, as the use of the term "beckit" to mean a chough is not found before the 19th century.[58] Regardless of its origin, the chough is still used in heraldry as a symbol of Becket, and appears in the arms of several persons and institutions associated with him, most notably in the arms of the city of Canterbury.[59]

Other nations

This species has been depicted on the stamps of Bhutan, The Gambia, Turkmenistan and Yugoslavia.[60] It is the animal symbol of the island of La Palma.[61]

See also

- List of animal and plant symbols of the Canary Islands

References

- BirdLife International (2016). "Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22705916A87384853. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22705916A87384853.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Linnaeus, C (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii). p. 118.

U. atra, rostro pedibusque rubris

- Tunstall, Marmaduke (1771). Ornithologia Britannica: seu Avium omnium Britannicarum tam terrestrium, quam aquaticarum catalogus, sermone Latino, Anglico et Gallico redditus (in Latin). London, J. Dixwell. p. 2.

- "Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax (Linnaeus, 1758)". BTOWeb BirdFacts. British Trust for Ornithology. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "ITIS Standard Report Page: Pyrrhocorax". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- Goodwin, Derek; Gillmor, Robert (1976). Crows of the World. London: British Museum (Natural History). p. 151. ISBN 0-565-00771-8.

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9. 406–8

- "ITIS Standard Report Page: Corcorax". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- Madge, Steve; Burn, Hilary (1994). Crows and jays: a guide to the crows, jays and magpies of the world. A&C Black. pp. 133–5. ISBN 0-7136-3999-7.

- "The Cornish Chough". Cornwall Council. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- Vieillot, Louis Jean Pierre (1817). Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle (in French). volume 8, 12.

- Vaurie, Charles (May 1954). "Systematic Notes on Palearctic Birds. No. 4 The Choughs (Pyrrhocorax)". American Museum Novitates (1658). hdl:2246/3595.

- Rand, Austin Loomer; Vaurie, Charles (1955). "A new chough from the highlands of Abyssinia". Bulletin of the British Ornithologists' Club. 75: 28.

- Gmelin, Johann Friedrich (1774). Reise durch Russland (in German). St. Petersburg. volume 3, 365.

- Gould, John (1862). "Two new species of hummingbird, a new Fregilus from the Himalayas and a new species of Prion". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 125.

- Stresemann, Erwin (1928). "Die Vögel der Elburs Expedition 1927". Journal of Ornithology (in German). 76 (2): 313–326. doi:10.1007/BF01940684. S2CID 27450092.

- Swinhoe, Robert (1871). "A revised catalogue of the birds of China and its islands, with descriptions of new species, references to former notes, and occasional remarks". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London: 383.

- Milne-Edwards, Alphonse; Lartet, Édouard; Christy, Henry, eds. (1875). Reliquiae aquitanicae: being contributions to the archaeology and palaeontology of Pèrigord and the adjoining provinces of Southern France. London: Williams. pp. 226–247.

- Mourer-Chauviré, Cécile (1975). "Les oiseaux du Pléistocène moyen et supérieur de France". Documents des Laboratoires de Géologie de la Faculté des Sciences de Lyon (in French). 64.

- Laiolo, Paola; Rolando, Antonio; Delestrade, Anne; De Sanctis, Augusto (2004). "Vocalizations and morphology: interpreting the divergence among populations of Red-billed Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and Alpine Chough P. graculus". Bird Study. 51 (3): 248–255. doi:10.1080/00063650409461360.

- Snow, David; Perrins, Christopher M., eds. (1998). The Birds of the Western Palearctic concise edition (2 volumes). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854099-X. 1466–68

- Blanco, Guillermo; Tella, José Luis; Torre, Ignacio (Summer 1996). "Age and sex determination of monomorphic non-breeding choughs: a long-term study" (PDF). Journal of Field Ornithology. 67 (3): 428–433.

- Laiolo, Paola; Rolando, Antonio; Delestrade, Anne; de Sanctis, Augusto (May 2001). "Geographical Variation in the Calls of the Choughs". The Condor. 103 (2): 287–297. doi:10.1650/0010-5422(2001)103[0287:GVITCO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0010-5422. S2CID 85866352.

- "Chough". Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Retrieved 5 February 2008.

- "Cornwall Chough Project". Projects. Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- Rolando, A; Laiolo, P (April 1997). "A comparative analysis of the diets of the chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax and the alpine chough Pyrrhocorax graculus coexisting in the Alps". Ibis. 139 (2): 388–395. doi:10.1111/j.1474-919X.1997.tb04639.x.

- Reid, J. M.; Bignal, E. M.; Bignal, S.; McCracken, D. I.; Monaghan, P. (2003). "Environmental variability, life-history covariation and cohort effects in the red-billed chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax". Journal of Animal Ecology. 72 (1): 36–46. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2656.2003.00673.x. JSTOR 3505541.

- Roberts, P. J. (1985). "The choughs of Bardsey". British Birds. 78 (5): 217–32.

- Ali, Salim; Ripley, S Dillon (1986). Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Vol. 5 (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 239–242. ISBN 0-19-562063-1.

- "Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax (breeding)" (PDF). Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- Stillman, Richard A.; Bignal, Eric M.; McCracken, David I.; Ovenden, Gy N. (1998). "Clutch and egg size in the Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax on Islay, Scotland". Bird Study. 45: 122–126. doi:10.1080/00063659809461085.

- Laiolo, P.; Bignal, E.M.; Patterson, I.J. (1998). "The dynamics of parental care in Choughs (Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax)". Journal of Ornithology. 139 (3): 297–305. doi:10.1007/BF01653340. S2CID 42610400.

- Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Anderson, John C. (2005). Birds of South Asia. The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution and Lynx Edicions. pp. 597–598.

- Mccanch, Norman (November 2000). "The relationship between Red-Billed Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax (L) breeding populations and grazing pressure on the Calf of Man". Bird Study. 47 (3): 295–303. doi:10.1080/00063650009461189. S2CID 85161238.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Tella, José Luis; Torre, Ignacio (July 1998). "Traditional farming and key foraging habitats for chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax conservation in a Spanish pseudosteppe landscape". Journal of Applied Ecology. 35 (23): 232–239. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2664.1998.00296.x. JSTOR 2405122.

- Roberts, P. J. (1983). "Feeding habitats of the Chough on Bardsey Island (Gwynedd)". Bird Study. 30 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1080/00063658309476777.

- Morris, Rev. Francis Orpen (1862). A history of British birds, volume 2. London, Groombridge and Sons. p. 29.

- Wall, Stephen B. Vander (1990). Food hoarding in animals. University of Chicago Press. p. 306. ISBN 0-226-84735-7.

- "A year in the life of Choughs". BirdWatch Ireland. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- "Release Update December 2003" (PDF). Operation Chough. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- Rolando, Antonio; Caldoni, Riccardo; De Sanctis, Augusto; Laiolo, Paola (2001). "Vigilance and neighbour distance in foraging flocks of red-billed choughs, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax". Journal of Zoology. 253 (2): 225–232. doi:10.1017/S095283690100019X.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Tella, José Luis (August 1997). "Protective association and breeding advantages of choughs nesting in lesser kestrel colonies". Animal Behaviour. 54 (2): 335–342. doi:10.1006/anbe.1996.0465. hdl:10261/58091. PMID 9268465. S2CID 38852266.

- Soler, Manuel; Palomino, Jose Javier; Martinez, Juan Gabriel; Soler, Juan Jose (1995). "Communal parental care by monogamous magpie hosts of fledgling Great Spotted Cuckoos" (PDF). The Condor. 97 (3): 804–810. doi:10.2307/1369188. JSTOR 1369188. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Merino, Santiago; Tella, Joseé Luis; Fargallo, Juan A; Gajon, A (1997). "Hematozoa in two populations of the threatened red-billed chough in Spain". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 33 (3): 642–5. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-33.3.642. PMID 9249715. S2CID 9353982.

- Palinauskas, Vaidas; Markovets, Mikhail Yu; Kosarev, Vladislav V; Efremov, Vladislav D; Sokolov Leonid V; Valkiûnas, Gediminas (2005). "Occurrence of avian haematozoa in Ekaterinburg and Irkutsk districts of Russia". Ekologija. 4: 8–12.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Tella, Jose Luis; Potti, Jaime (September 1997). "Feather Mites on Group-Living Red-Billed Choughs: A Non-Parasitic Interaction?" (PDF). Journal of Avian Biology. 28 (3): 197–206. doi:10.2307/3676970. JSTOR 3676970. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2013.

- Blanco, Guillermo; Fargallo, Juan A.; Tella, José Luis; Cuevas; Jesús A. (1997). "Role of buildings as nest-sites in the range expansion and conservation of choughs Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax in Spain" (PDF). Biological Conservation. 79 (2–3): 117–122. doi:10.1016/S0006-3207(96)00118-8. hdl:10261/58104.

- Reyes, Juan Carlos Rando (2007). "New fossil records of choughs genus Pyrhocorax in the Canary Islands: hypotheses to explain its extinction and current narrow distribution". Ardeola. 54 (2): 185–195.

- "Red-billed Chough". Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- "Choughs: Field Programme". Birds on the Edge. Durrell Wildlife Conservation Trust. Archived from the original on 23 December 2018. Retrieved 15 July 2019.

- de Vries, Ad (1976). Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company. p. 97. ISBN 0-7204-8021-3.

- "Book V. The departure of Ulysses from Calypso". The Odyssey of Homer, translated by Alexander Pope. Archived from the original on 13 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2008.

- Defoe, Daniel (1962). A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, divided into circuits or journies (Appendix To Letter III). London, UK: Dent. pp. 247–248.

- Newlyn, Lucy (2005). Chatter of Choughs: An Anthology Celebrating the Return of Cornwall's Legendary Bird. Wilkinson, Lucy (illustrator). Hypatia Publications. p. 31. ISBN 1-872229-49-2.

- Carrell, Severin (27 January 2002). "Cornish chuffed at the return of the chough". The Independent. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2010.

- "Keeping the Twelve Days of Christmas". Fullhomelydivinity.org. Retrieved 6 February 2008.

- The age of heraldry started in England c.1200-1215

- Humphery-Smith, Cecil (January 1971). "Heraldry and the Martyrdom of Archbishop Thomas Becket". The Coat of Arms. The Heraldry Society (85).

- "The City Arms of Canterbury". Canterbury City Council. Archived from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 16 December 2011.

- Scharning, Kjell. "Red-billed Chough Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax". Theme Birds on Stamps. Retrieved 4 June 2009.

- "Símbolos de la naturaleza para las Islas Canarias" [Natural Symbols for the Canary Islands]. Ley No. 7/1991 of 30 April 1991 (in Spanish). Vol. 151. pp. 20946–20497 – via BOE.