Qianling Mausoleum

The Qianling Mausoleum (Chinese: 乾陵; pinyin: Qiánlíng) is a Tang dynasty (618–907) tomb site located in Qian County, Shaanxi province, China, and is 85 km (53 mi) northwest from Xi'an.[1] Built in 684 (with additional construction until 706), the tombs of the mausoleum complex house the remains of various members of the House of Li, the imperial family of the Tang dynasty. This includes Emperor Gaozong (r. 649–83), as well as his wife, Wu Zetian, who assumed the Tang throne and became China's only reigning female emperor from 690–705. The mausoleum is renowned for its many Tang dynasty stone statues located above ground and the mural paintings adorning the subterranean walls of the tombs. Besides the main tumulus mound and underground tomb of Emperor Gaozong and Wu Zetian, there are 17 smaller attendant tombs, or peizang mu.[2] Presently, only five of these attendant tombs have been excavated by archaeologists, three belonging to members of the imperial family, one to a chancellor, and the other to a general of the left guard.[3] The Shaanxi Administration of Cultural Heritage declared in 2012 that no further excavations would take place for at least 50 years.[4]

Partial view of the Mausoleum | |

Shown within China | |

| Location | Qian County, Shaanxi province |

|---|---|

| Region | China |

| Coordinates | 34°34′28″N 108°12′51″E |

History

Emperor Gaozong's mausoleum complex was completed in 684 following his death a year earlier.[8] After her death, Wu Zetian was interred in a joint burial with Emperor Gaozong at Qianling on July 2, 706.[9][10] There are Tang dynasty funerary epitaphs in the tombs of her son Li Xián (Crown Prince Zhanghuai, 653–84), grandson Li Chongrun (Prince of Shao, posthumously honored Crown Prince Yide, 682–701), and granddaughter Li Xianhui (Lady Yongtai, posthumously honored as Princess Yongtai, 684–701) in the mausoleum that are inscribed with the date of burial as 706 AD, allowing historians to accurately date the structures and artwork of the tombs.[11][12] In fact, the Sui and Tang dynasty practice of interring an epitaph that records the person's name, rank, and dates of death and burial was consistent amongst tombs for the imperial family and high court officials.[12] Both the Old Book of Tang and New Book of Tang record that, in 706, Wu Zetian's son Emperor Zhongzong (r. 684, 705–10, Li Chongrun's and Li Xianhui's father and Li Xián's brother) exonerated the victims of Wu Zetian's political purges and provided them with honorable burials, including the princess and two princes.[13] Besides the attendant tombs of the royal family members, two others that have been excavated belong to Chancellor Xue Yuanchao (622–83) and General of the Left Guard Li Jinxing.[3]

The five attendant tombs were opened and excavated in the 1960s and early 1970s.[14] In March 1995, there was an organized petition to the Chinese government about efforts to excavate Emperor Gaozong and Wu Zetian's tomb.[15]

Location

The mausoleum is located on Mount Liang, north of the Wei River, and 1,049 m (3,442 ft) above sea level.[7][16] The grounds of the mausoleum are flanked by valley to the east and canyon to the west.[16] Although there are tumulus mounds to mark where each tomb is located, most of the tomb structures are subterranean. The tumulus mounds on the southern peaks are called Naitoushan or "Nipple Hills", due to their resemblance to the shape of nipples.[7] The Nipple Hills, with towers erected on the top of each to accentuate the hills' name, form a gateway into Qianling Mausoleum.[16] The main tumulus mound is on the northern peak; it is the tallest of the mounds and is the burial place of Gaozong and Wu Zetian.[16] Halfway up this northern peak, the builders of the site dug a 61 m (200 ft) long and 4 m (13 ft) wide tunnel into the rock of the mountain that leads to the inner tomb chambers located deep within the mountain.[17] The complex was originally enclosed by two walls, the remains of which have been discovered today, including what was four gatehouses of the inner wall.[16] The inner wall was 2.4 m (7.8 ft) thick, with a total perimeter of 5920 m (19,422 ft) enclosing a trapezoidal area of 240,000 m2 (787,400 ft2).[7][16] Only some corner parts of the outer wall have been discovered. During the Tang dynasty, there were hundreds of residential houses that surrounded Qianling, inhabited by families that maintained the grounds and buildings of the mausoleum.[6] The remains of some of these houses have since been discovered. The building foundation of the timber offering hall situated at the south gate of the mausoleum's inner wall has also been discovered.[8]

Spirit way

Leading into the mausoleum is a spirit way, which is flanked on both sides with stone statues like the later tombs of the Song dynasty and Ming Dynasty Tombs. The Qianling statues include horses, winged horses, horses with grooms, lions, ostriches, officials, and foreign envoys.[18] The khan of the Western Turks presented an ostrich to the Tang court in 620 and the Tushara Kingdom sent another in 650; in carved reliefs of Qianling dated c. 683, traditional Chinese phoenixes are modelled on the body of ostriches.[19] Historian Tonia Eckfeld states that the artistic emphasis on the exotic foreign tribute of the ostrich at the mausoleum was "a sign of the greatness of China and the Chinese emperor, not of the foreigners who sent them, or of the places from which they came".[19] Eckfeld also asserts that the 61 statues of foreign diplomats sculpted in the 680s represents the "far-reaching power and international standing" of the Tang Dynasty.[20] These statues, now headless, represent the foreign diplomats who were present at Emperor Gaozong's funeral.[1] Historian Angela Howard notes that along the spirit ways of the auxiliary tombs—such as Li Xianhui's—the statues are smaller, of lesser quality, and fewer in number than the main spirit way of Qianling leading to Emperor Gaozong and Wu's burial.[21] Besides the statues, there are also flanking sets of octagonal stone pillars meant to ward off evil spirits.[6] A 6.3 m (20.7 ft) tall tiered stele dedicated to Emperor Gaozong is also located along the path, with a written inscription commemorating his achievements; this is flanked by Wu Zetian's stele which has no written inscriptions.[6] An additional stele by the main tumulus was erected by the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1735–96) during the mid-Qing dynasty.[1]

Tombs

The tomb chambers of Emperor Gaozong and Empress Wu are located deep within Mount Liang, a trend that was set by Emperor Taizong (r. 626–49) with his burial at Mount Jiuzong.[22] Of the 18 emperors of the Tang dynasty, 14 of these had natural mountains serving as the earthen mounds for their tombs.[22] Only members of the imperial family were allowed to have their tombs located within natural mountains; tombs for officials and nobles featured man-made tumulus mounds and tomb chambers that were totally underground.[23] Xinian Fu wrote that children of emperors were allowed tombs in the shape of truncated pyramids, but high-ranking officials and lesser tomb constructors could only have conical mounds.[23] The conical tombs of officials were allowed to have one wall surrounding it, but only one gate—positioned to the south—was permitted.[23] The attendant tombs feature truncated pyramid mounds above underground chambers that are approached by declining diagonal ramps with ground-level entrances.[24] There are six vertical shafts for the ramps of each of these tombs which allowed goods to be lowered into the side niches of the ramps.[24]

The main hall in each of these underground tombs leads to two four-sided brick-laden burial chambers connected by a short corridor;[24] these chambers feature domed ceilings.[24] The tomb of Li Xian features real fully stone doors, a tomb trend apparent in the Han and Western Jin dynasties that became more common by the time of the Northern Qi dynasty.[25] The stylistic stone door of Lou Rui's tomb of 570 closely resembles that of Tang stone doors, such as the one in Li Xian's tomb.[25]

Unlike many other Tang dynasty tombs, the treasures within the imperial tombs of the Qianling Mausoleum were never stolen by grave robbers.[26] In fact, in Li Chongrun's tomb alone, there were found over a thousand items of gold, copper, iron, ceramic figurines, three-glaze colored figurines, and three-glaze pottery wares.[27] Altogether, the tombs of Li Xian, Li Chongrun, and Li Xianhui had over 4,300 tomb articles when they were unearthed by archaeologists.[7] However, the attendant tombs of the mausoleum were raided by grave robbers.[7] Among the ceramic figurines found in Li Chongrun's tomb were horses with gilt decoration supporting armed and armored soldiers, horsemen playing flutes, blowing trumpets, and waving whips to spur their horses.[7] Ceramic sculptures found in the tomb of Li Xian included figurines of civil officials, warriors, and tomb guardian beasts, all of which were over a meter (3 ft) in height.[7]

Li Xianhui

Li Xianhui was a daughter of the Emperor Zhongzong of Tang and Empress Wei. She was likely killed at the age of 16 by her grandmother Wu Zetian, along with her husband. After Wu Zetian's death, when her father came to the throne, she was reburied in a grand tomb in the Qianling Mausoleum in 705.[28] Her tomb was discovered in 1960, and excavated from 1964. It had been robbed in the past, likely soon after the burial, and items in precious materials taken, but the thieves had not bothered with the over 800 pottery tomb figures, and the extensive frescos were untouched. The robbers had left in a hurry, leaving silver items scattered around, and the corpse of one of their number. The tomb had a flattened pyramid rising 12 metres above ground, and a long sloping entrance tunnel lined with frescos, leading to an antechamber and the tomb chamber itself, 12 metres below ground level with a high domed roof.[29]

Murals

The tombs excavated for Li Xian, Li Chongrun, and Li Xianhui are all decorated with mural paintings and feature multiple shaft entrances and arched chambers.[32] Historian Mary H. Fong states that the tomb murals in the subterranean halls of Li Xián's, Li Chongrun's, and Li Xianhui's tombs are representative of anonymous but professional tomb decorators rather than renowned court painters of handscrolls.[13] Although primarily funerary art, Fong asserts that these Tang tomb murals are "sorely needed references" to the sparse amount of description offered in Tang era documents about painting, such as the Tang Chao minghua lu ('Celebrated Painters of the Tang Dynasty') by Zhu Jingxuan in the 840s and the Lidai Minghua ji ('A Record of the Famous Painters of the Successive Dynasties') by Zhang Yanyuan in 847.[33] Fong also asserts that the painting skill of portraying "animation through spirit consonance" or qiyun shendong—an art critique associated with renowned Tang dynasty painters like Yan Liben, Zhou Fang, and Chen Hong—was achieved by the anonymous Tang dynasty tomb painters.[34] Fong writes:

The "Palace Guard" and the "Two Seated Attendants" from Prince Zhang Huai's tomb are especially outstanding in this respect. Not only are the relative differences in age achieved, but it is evident that the robust guard officer who stands at attention displays an attitude of respectful self-assurance; and the seated pair are deeply engrossed in a serious conversation.[35]

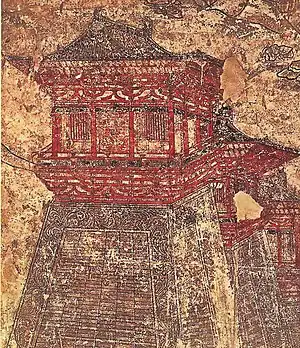

Another important feature in the murals of the tomb was the representation of architecture. Although there are numerous examples of existing Tang stone and brick pagoda towers for architectural historians to examine, there are only six remaining wooden halls that have survived from the 8th and 9th centuries.[36] Only the rammed earth foundations of the great palaces of the Tang capital at Chang'an have survived. However, some of the mural scenes of timber architecture in Li Chongrun's tomb at Qianling have been suggested by historians as representative of the Eastern Palace, residence of the crown prince during the Tang dynasty.[23] According to historian Fu Xinian, not only do the murals of Li Chongrun's tomb represent buildings of the Tang capital, but also "the number of underground chambers, ventilation shafts, compartments, and air wells have been seen as indications of the number of courtyards, main halls, rooms, and corridors in residences of tomb occupants when they were alive."[23][37] The underground hall of the descending ramp approaching Li Chongrun's tomb chambers, as well as the gated entrance to the front chamber, feature murals of multiple-bodied que gate towers similar to those whose foundations were surveyed at Chang'an.[23][37]

Ann Paludan, an Honorary Fellow of Durham University, provides captions in her Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors (1998) for the following pictures of Qianling tomb murals:

"In this mural foreign ambassadors are being received at court. The two elegantly clad figures on the right are from Korea, the bare-headed, large-nosed figure in the centre is an envoy from the west. Mural from Li Xian's tomb, Qianling, Shaanxi, 706."[38]

"In this mural foreign ambassadors are being received at court. The two elegantly clad figures on the right are from Korea, the bare-headed, large-nosed figure in the centre is an envoy from the west. Mural from Li Xian's tomb, Qianling, Shaanxi, 706."[38] "A group of palace ladies in the gardens while a hoopoe flies by. Mural, tomb of Emperor Gaozong's 6th son, Li Xian, Qianling, Shaanxi, 706."[39]

"A group of palace ladies in the gardens while a hoopoe flies by. Mural, tomb of Emperor Gaozong's 6th son, Li Xian, Qianling, Shaanxi, 706."[39] "Early 8th century murals in Prince Yide's tomb give an idea of the magnificence of Chang'an's city walls with their towering gate and corner towers."[40] (The tower depicted in this mural section is a que tower.)

"Early 8th century murals in Prince Yide's tomb give an idea of the magnificence of Chang'an's city walls with their towering gate and corner towers."[40] (The tower depicted in this mural section is a que tower.) "A group of eunuchs. Mural from the tomb of the prince Zhanghuai, 706, Qianling, Shaanxi."[41]

"A group of eunuchs. Mural from the tomb of the prince Zhanghuai, 706, Qianling, Shaanxi."[41]

See also

- Chinese pyramids

- Zhao Mausoleum

References

Citations

- Valder (2002), 80.

- Eckfeld (2005), 26.

- Eckfeld (2005), 26–27.

- Zhang, Chan (17 January 2012). "No excavation of Qianling Mausoleum, official says". China News Service. Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- "The Qianling Mausoleum". The Government Website of Shaanxi Province. Archived from the original on 5 April 2016. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- Eckfeld (2005), 23.

- Qianling Mausoleum of the Tang Dynasty Archived 2014-11-27 at the Wayback Machine. China Internet Information Center. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- Fu, "The Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties," 107.

- Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 208.

- Academia Sinica's Chinese and Common Calendar Converter.

- Fong (1984), 35–36.

- Fong (1991), 147.

- Fong (1984), 36.

- Eckfeld (2005), 29.

- Jay (1996), 228, footnote 59.

- Eckfeld (2005), 21.

- Turner (1996), 780.

- Eckfeld (2005), 22–23.

- Eckfeld (2005), 23–24.

- Eckfeld (2005), 25.

- Howard (2006), 71.

- Fu, "The Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties," 106.

- Fu, "The Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties," 108.

- Steinhardt (1997), 274.

- Fong (1991), 155.

- Dillon (1998), 311.

- The Tomb of Prince Yide. TravelChinaGuide. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- Watson, 136

- Watson, 136–141,

- The Tomb of Princess Yongtai. TravelChinaGuide. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- Shaanxi History Museum, archived from the original on 4 May 2005, retrieved 12 February 2008.

- Guo (2004), 12.

- Fong (1984), 37.

- Fong (1984), 38.

- Fong (1984), 53.

- Steinhardt (2004), 223, 228–229, 238.

- Steinhardt (1990), 103–108.

- Paludan (1998), 98.

- Paludan (1998), 103.

- Paludan (1998), 106.

- Paludan (1998), 115.

Sources

- Dillon, Michael. (1998). China: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Surrey: Curzon Press. ISBN 0-7007-0439-6.

- Eckfeld, Tonia. (2005). Imperial Tombs in Tang China, 618–907: The Politics of Paradise. New York: Routledge: ISBN 0-415-30220-X.

- Fong, Mary H. "Tang Tomb Murals Reviewed in the Light of Tang Texts on Painting," Artibus Asiae (Volume 45, Number 1, 1984): 35–72.

- Fong, Mary H. "Antecedents of Sui-Tang Burial Practices in Shaanxi", Artibus Asiae (Volume 51, Number 3/4, 1991): 147–198.

- Fu, Xinian. (2002). "The Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties", in Chinese Architecture, ed. Nancy Steinhardt, 91–135. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-09559-7.

- Guo, Qinghua. "Tomb Architecture of Dynastic China: Old and New Questions," Architectural History (Volume 47, 2004): 1–24.

- Howard, Angela Falco. (2006). Chinese Sculpture. New Haven: Yale University and Foreign Languages Press. ISBN 0-300-10065-5.

- Jay, Jennifer W. "Imagining Matriarchy: "Kingdoms of Women" in Tang China", Journal of the American Oriental Society (Volume 116, Number 2, 1996): 220–229.

- Paludan, Ann. (1998). Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: the Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 0-500-05090-2.

- Turner, Jane. (1996). The Dictionary of Art. New York: The Grove Press. ISBN 1-884446-00-0

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. (1990). Chinese Imperial City Planning. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-2196-3.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. (1997). Liao Architecture. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0-8248-1719-2.

- Steinhardt, Nancy Shatzman. "The Tang Architectural Icon and the Politics of Chinese Architectural History", The Art Bulletin (Volume 86, Number 2, 2004): 228–254

- Valder, Peter. (2002). Gardens in China. Portland: The Timber Press, Inc. ISBN 0-88192-555-1.

- Watson, William, Genius of China (exhibition, Royal Academy of Arts), 1973, Times Newspapers Ltd, ISBN 0723001073