Reverse osmosis

Reverse osmosis (RO) is a water purification process that uses a partially permeable membrane to separate ions, unwanted molecules and larger particles from drinking water. In reverse osmosis, an applied pressure is used to overcome osmotic pressure, a colligative property that is driven by chemical potential differences of the solvent, a thermodynamic parameter. Reverse osmosis can remove many types of dissolved and suspended chemical species as well as biological ones (principally bacteria) from water, and is used in both industrial processes and the production of potable water. The result is that the solute is retained on the pressurized side of the membrane and the pure solvent is allowed to pass to the other side. To be "selective", this membrane should not allow large molecules or ions through the pores (holes), but should allow smaller components of the solution (such as solvent molecules, e.g., water, H2O) to pass freely.[1]

| Water desalination

|

|---|

| Methods |

|

In the normal osmosis process, the solvent naturally moves from an area of low solute concentration (high water potential), through a membrane, to an area of high solute concentration (low water potential). The driving force for the movement of the solvent is the reduction in the Gibbs free energy of the system when the difference in solvent concentration on either side of a membrane is reduced, generating osmotic pressure due to the solvent moving into the more concentrated solution. Applying an external pressure to reverse the natural flow of pure solvent, thus, is reverse osmosis. The process is similar to other membrane technology applications.

Reverse osmosis differs from filtration in that the mechanism of fluid flow is by osmosis across a membrane. The predominant removal mechanism in membrane filtration is straining, or size exclusion, where the pores are 0.01 micrometers or larger, so the process can theoretically achieve perfect efficiency regardless of parameters such as the solution's pressure and concentration. Reverse osmosis instead involves solvent diffusion across a membrane that is either nonporous or uses nanofiltration with pores 0.001 micrometers in size. The predominant removal mechanism is from differences in solubility or diffusivity, and the process is dependent on pressure, solute concentration, and other conditions.[2]

Reverse osmosis is most commonly known for its use in drinking water purification from seawater, removing the salt and other effluent materials from the water molecules.[3]

History

A process of osmosis through semipermeable membranes was first observed in 1748 by Jean-Antoine Nollet. For the following 200 years, osmosis was only a phenomenon observed in the laboratory. In 1950, the University of California at Los Angeles first investigated desalination of seawater using semipermeable membranes. Researchers from both University of California at Los Angeles and the University of Florida successfully produced fresh water from seawater in the mid-1950s, but the flux was too low to be commercially viable[4] until the discovery at University of California at Los Angeles by Sidney Loeb and Srinivasa Sourirajan[5] at the National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, of techniques for making asymmetric membranes characterized by an effectively thin "skin" layer supported atop a highly porous and much thicker substrate region of the membrane. John Cadotte, of Filmtec corporation, discovered that membranes with particularly high flux and low salt passage could be made by interfacial polymerization of m-phenylene diamine and trimesoyl chloride. Cadotte's patent on this process[6] was the subject of litigation and has since expired. Almost all commercial reverse-osmosis membrane is now made by this method. By 2019, there were approximately 16,000 desalination plants operating around the world, producing around 95 million cubic metres per day (25 billion US gallons per day) of desalinated water for human use. Around half of this capacity was in the Middle East and North Africa region.[7]

In 1977 Cape Coral, Florida became the first municipality in the United States to use the RO process on a large scale with an initial operating capacity of 11.35 million liters (3 million US gal) per day. By 1985, due to the rapid growth in population of Cape Coral, the city had the largest low-pressure reverse-osmosis plant in the world, capable of producing 56.8 million liters (15 million US gal) per day (MGD).[8]

Formally, reverse osmosis is the process of forcing a solvent from a region of high solute concentration through a semipermeable membrane to a region of low-solute concentration by applying a pressure in excess of the osmotic pressure. The largest and most important application of reverse osmosis is the separation of pure water from seawater and brackish waters; seawater or brackish water is pressurized against one surface of the membrane, causing transport of salt-depleted water across the membrane and emergence of potable drinking water from the low-pressure side.

The membranes used for reverse osmosis have a dense layer in the polymer matrix—either the skin of an asymmetric membrane or an interfacially polymerized layer within a thin-film-composite membrane—where the separation occurs. In most cases, the membrane is designed to allow only water to pass through this dense layer while preventing the passage of solutes (such as salt ions). This process requires that a high pressure be exerted on the high-concentration side of the membrane, usually 2–17 bar (30–250 psi) for fresh and brackish water, and 40–82 bar (600–1200 psi) for seawater, which has around 27 bar (390 psi)[9] natural osmotic pressure that must be overcome. This process is best known for its use in desalination (removing the salt and other minerals from sea water to produce fresh water), but since the early 1970s, it has also been used to purify fresh water for medical, industrial and domestic applications.

Fresh water applications

Drinking water purification

Around the world, household drinking water purification systems, including a reverse osmosis step, are commonly used for improving water for drinking and cooking.

Such systems typically include a number of steps:

- a sediment filter to trap particles, including rust and calcium carbonate

- optionally, a second sediment filter with smaller pores

- an activated carbon filter to trap organic chemicals and chlorine, which will attack and degrade certain types of thin-film composite membrane

- a reverse osmosis filter, which is a thin-film composite membrane

- optionally, an ultraviolet lamp for sterilizing any microbes that may escape filtering by the reverse osmosis membrane

- optionally, a second carbon filter to capture those chemicals not removed by the reverse osmosis membrane

In some systems, the carbon prefilter is omitted, and a cellulose triacetate membrane is used. CTA (cellulose triacetate) is a paper by-product membrane bonded to a synthetic layer and is made to allow contact with chlorine in the water. These require a small amount of chlorine in the water source to prevent bacteria from forming on it. The typical rejection rate for CTA membranes is 85–95%.

The cellulose triacetate membrane is prone to rotting unless protected by chlorinated water, while the thin-film composite membrane is prone to breaking down under the influence of chlorine. A thin-film composite (TFC) membrane is made of synthetic material, and requires chlorine to be removed before the water enters the membrane. To protect the TFC membrane elements from chlorine damage, carbon filters are used as pre-treatment in all residential reverse osmosis systems. TFC membranes have a higher rejection rate of 95–98% and a longer life than CTA membranes.

Portable reverse osmosis water processors are sold for personal water purification in various locations. To work effectively, the water feeding to these units should be under some pressure (280 kPa (40 psi) or greater is the norm).[10] Portable reverse osmosis water processors can be used by people who live in rural areas without clean water, far away from the city's water pipes. Rural people filter river or ocean water themselves, as the device is easy to use (saline water may need special membranes). Some travelers on long boating, fishing, or island camping trips, or in countries where the local water supply is polluted or substandard, use reverse osmosis water processors coupled with one or more ultraviolet sterilizers.

In the production of bottled mineral water, the water passes through a reverse osmosis water processor to remove pollutants and microorganisms. In European countries, though, such processing of natural mineral water (as defined by a European directive[11]) is not allowed under European law. In practice, a fraction of the living bacteria can and do pass through reverse osmosis membranes through minor imperfections, or bypass the membrane entirely through tiny leaks in surrounding seals. Thus, complete reverse osmosis systems may include additional water treatment stages that use ultraviolet light or ozone to prevent microbiological contamination.

Membrane pore sizes can vary from 0.1 to 5,000 nm depending on filter type. Particle filtration removes particles of 1 µm or larger. Microfiltration removes particles of 50 nm or larger. Ultrafiltration removes particles of roughly 3 nm or larger. Nanofiltration removes particles of 1 nm or larger. Reverse osmosis is in the final category of membrane filtration, hyperfiltration, and removes particles larger than 0.1 nm.[12] For the purposes of household water filtration when there is no need to remove excessive dissolved minerals (soften water), the alternative to reverse osmosis filtration is an activated carbon filter with a microfiltration membrane.

Decentralized use: solar-powered reverse osmosis

A solar-powered desalination unit produces potable water from saline water by using a photovoltaic system that converts solar power into the required energy for reverse osmosis. Due to the extensive availability of sunlight across different geographies, solar-powered reverse osmosis lends itself well to drinking water purification in remote settings lacking an electricity grid. Moreover, solar energy overcomes the usually high-energy operating costs as well as greenhouse emissions of conventional reverse osmosis systems, making it a sustainable freshwater solution compatible to developing contexts. For example, a solar-powered desalination unit designed for remote communities has been successfully tested in the Northern Territory of Australia.[13]

While the intermittent nature of sunlight and its variable intensity throughout the day makes PV efficiency prediction difficult and desalination during night time challenging, several solutions exist. For example, batteries, which provide the energy required for desalination in non-sunlight hours can be used to store solar energy in daytime. Apart from the use of conventional batteries, alternative methods for solar energy storage exist. For example, thermal energy storage systems solve this storage problem and ensure constant performance even during non-sunlight hours and cloudy days, improving overall efficiency.[14]

Military use: the reverse osmosis water purification unit

A reverse osmosis water purification unit (ROWPU) is a portable, self-contained water treatment plant. Designed for military use, it can provide potable water from nearly any water source. There are many models in use by the United States armed forces and the Canadian Forces. Some models are containerized, some are trailers, and some are vehicles unto themselves.

Each branch of the United States armed forces has their own series of reverse osmosis water purification unit models, but they are all similar. The water is pumped from its raw source into the reverse osmosis water purification unit module, where it is treated with a polymer to initiate coagulation. Next, it is run through a multi-media filter where it undergoes primary treatment by removing turbidity. It is then pumped through a cartridge filter which is usually spiral-wound cotton. This process clarifies the water of any particles larger than 5 µm and eliminates almost all turbidity.

The clarified water is then fed through a high-pressure piston pump into a series of vessels where it is subject to reverse osmosis. The product water is free of 90.00–99.98% of the raw water's total dissolved solids and by military standards, should have no more than 1000–1500 parts per million by measure of electrical conductivity. It is then disinfected with chlorine and stored for later use.

Water and wastewater purification

Rain water collected from storm drains is purified with reverse osmosis water processors and used for landscape irrigation and industrial cooling in Los Angeles and other cities, as a solution to the problem of water shortages.

In industry, reverse osmosis removes minerals from boiler water at power plants.[15] The water is distilled multiple times. It must be as pure as possible so it does not leave deposits on the machinery or cause corrosion. The deposits inside or outside the boiler tubes may result in under-performance of the boiler, reducing its efficiency and resulting in poor steam production, hence poor power production at the turbine.

It is also used to clean effluent and brackish groundwater. The effluent in larger volumes (more than 500 m3/day) should be treated in an effluent treatment plant first, and then the clear effluent is subjected to reverse osmosis system. Treatment cost is reduced significantly and membrane life of the reverse osmosis system is increased.

The process of reverse osmosis can be used for the production of deionized water.[16]

Reverse osmosis process for water purification does not require thermal energy. Flow-through reverse osmosis systems can be regulated by high-pressure pumps. The recovery of purified water depends upon various factors, including membrane sizes, membrane pore size, temperature, operating pressure, and membrane surface area.

In 2002, Singapore announced that a process named NEWater would be a significant part of its future water plans. It involves using reverse osmosis to treat domestic wastewater before discharging the NEWater back into the reservoirs.

Food industry

In addition to desalination, reverse osmosis is a more economical operation for concentrating food liquids (such as fruit juices) than conventional heat-treatment processes. Research has been done on concentration of orange juice and tomato juice. Its advantages include a lower operating cost and the ability to avoid heat-treatment processes, which makes it suitable for heat-sensitive substances such as the protein and enzymes found in most food products.

Reverse osmosis is extensively used in the dairy industry for the production of whey protein powders and for the concentration of milk to reduce shipping costs. In whey applications, the whey (liquid remaining after cheese manufacture) is concentrated with reverse osmosis from 6% total solids to 10–20% total solids before ultrafiltration processing. The ultrafiltration retentate can then be used to make various whey powders, including whey protein isolate. Additionally, the ultrafiltration permeate, which contains lactose, is concentrated by reverse osmosis from 5% total solids to 18–22% total solids to reduce crystallization and drying costs of the lactose powder.

Although use of the process was once avoided in the wine industry, it is now widely understood and used. An estimated 60 reverse osmosis machines were in use in Bordeaux, France, in 2002. Known users include many of the elite-classed growths (Kramer) such as Château Léoville-Las Cases in Bordeaux.

Maple syrup production

In 1946, some maple syrup producers started using reverse osmosis to remove water from sap before the sap is boiled down to syrup. The use of reverse osmosis allows about 75–90% of the water to be removed from the sap, reducing energy consumption and exposure of the syrup to high temperatures. Microbial contamination and degradation of the membranes must be monitored.

Low-alcohol beer

When beer at normal alcohol concentration is subject to reverse osmosis, both water and alcohol pass across the membrane more readily than the other components, leaving a "beer concentrate". The concentrate is then diluted with fresh water to restore the non-volatile components to their original intensity.[17]

Hydrogen production

For small-scale hydrogen production, reverse osmosis is sometimes used to prevent formation of mineral deposits on the surface of electrodes.

Aquariums

Many reef aquarium keepers use reverse osmosis systems for their artificial mixture of seawater. Ordinary tap water can contain excessive chlorine, chloramines, copper, nitrates, nitrites, phosphates, silicates, or many other chemicals detrimental to the sensitive organisms in a reef environment. Contaminants such as nitrogen compounds and phosphates can lead to excessive and unwanted algae growth. An effective combination of both reverse osmosis and deionization is the most popular among reef aquarium keepers, and is preferred above other water purification processes due to the low cost of ownership and minimal operating costs. Where chlorine and chloramines are found in the water, carbon filtration is needed before the membrane, as the common residential membrane used by reef keepers does not cope with these compounds.

Freshwater aquarists also use reverse osmosis systems to duplicate the very soft waters found in many tropical water bodies. Whilst many tropical fish can survive in suitably treated tap water, breeding can be impossible. Many aquatic shops sell containers of reverse osmosis water for this purpose.

Window cleaning

An increasingly popular method of cleaning windows is the so-called "water-fed pole" system. Instead of washing the windows with detergent in the conventional way, they are scrubbed with highly purified water, typically containing less than 10 ppm dissolved solids, using a brush on the end of a long pole which is wielded from ground level. Reverse osmosis is commonly used to purify the water.

Landfill leachate purification

Treatment with reverse osmosis is limited, resulting in low recoveries on high concentration (measured with electrical conductivity) and fouling of the RO membranes. Reverse osmosis applicability is limited by conductivity, organics, and scaling inorganic elements such as CaSO4, Si, Fe and Ba. Low organic scaling can use two different technologies, one is using spiral wound membrane type of module, and for high organic scaling, high conductivity and higher pressure (up to 90 bars) disc tube modules with reverse-osmosis membranes can be used. Disc tube modules were redesigned for landfill leachate purification, that is usually contaminated with high levels of organic material. Due to the cross-flow with high velocity it is given a flow booster pump, that is recirculating the flow over the same membrane surface between 1.5 and 3 times before it is released as a concentrate. High velocity is also good against membrane scaling and allows successful membrane cleaning.

Power consumption for a disc tube module system

| Energy consumption per m3 leachate | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| name of module | 1-stage up to 75 bar | 2-stage up to 75 bar | 3-stage up to 120 bar |

| disc tube module | 6.1–8.1 kWh/m3 | 8.1–9.8 kWh/m3 | 11.2–14.3 kWh/m3 |

Desalination

Areas that have either no or limited surface water or groundwater may choose to desalinate. Reverse osmosis is an increasingly common method of desalination, because of its relatively low energy consumption.[18]

In recent years, energy consumption has dropped to around 3 kWh/m3 (11,000 J/L), with the development of more efficient energy recovery devices and improved membrane materials. According to the International Desalination Association, for 2011, reverse osmosis was used in 66% of installed desalination capacity (0.0445 of 0.0674 km³/day), and nearly all new plants.[19] Other plants mainly use thermal distillation methods: multiple-effect distillation and Multi-Stage Flash.

Sea-water reverse-osmosis (SWRO) desalination, a membrane process, has been commercially used since the early 1970s. Its first practical use was demonstrated by Sidney Loeb from University of California at Los Angeles in Coalinga, California, and Srinivasa Sourirajan of National Research Council, Canada. Because no heating or phase changes are needed, energy requirements are low, around 3 kWh/m3, in comparison to other processes of desalination, but are still much higher than those required for other forms of water supply, including reverse osmosis treatment of wastewater, at 0.1 to 1 kWh/m3. Up to 50% of the seawater input can be recovered as fresh water, though lower recoveries may reduce membrane fouling and energy consumption.

Brackish water reverse osmosis refers to desalination of water with a lower salt content than sea water, usually from river estuaries or saline wells. The process is substantially the same as sea water reverse osmosis, but requires lower pressures and therefore less energy.[1] Up to 80% of the feed water input can be recovered as fresh water, depending on feed salinity.

The Ashkelon sea water reverse osmosis desalination plant in Israel is the largest in the world.[20][21] The project was developed as a build-operate-transfer by a consortium of three international companies: Veolia water, IDE Technologies, and Elran.[22]

The typical single-pass sea water reverse osmosis system consists of:

- Intake

- Pretreatment

- High-pressure pump (if not combined with energy recovery)

- Membrane assembly

- Energy recovery (if used)

- Remineralisation and pH adjustment

- Disinfection

- Alarm/control panel

Pretreatment

Pretreatment is important when working with reverse osmosis and nanofiltration membranes due to the nature of their spiral-wound design. The material is engineered in such a fashion as to allow only one-way flow through the system. As such, the spiral-wound design does not allow for backpulsing with water or air agitation to scour its surface and remove solids. Since accumulated material cannot be removed from the membrane surface systems, they are highly susceptible to fouling (loss of production capacity). Therefore, pretreatment is a necessity for any reverse osmosis or nanofiltration system. Pretreatment in sea water reverse osmosis systems has four major components:

- Screening of solids: Solids within the water must be removed and the water treated to prevent fouling of the membranes by fine-particle or biological growth, and reduce the risk of damage to high-pressure pump components.

- Cartridge filtration: Generally, string-wound polypropylene filters are used to remove particles of 1–5 µm diameter.

- Dosing: Oxidizing biocides, such as chlorine, are added to kill bacteria, followed by bisulfite dosing to deactivate the chlorine, which can destroy a thin-film composite membrane. There are also biofouling inhibitors, which do not kill bacteria, but simply prevent them from growing slime on the membrane surface and plant walls.

- Prefiltration pH adjustment: If the pH, hardness and the alkalinity in the feedwater result in a scaling tendency when they are concentrated in the reject stream, acid is dosed to maintain carbonates in their soluble carbonic acid form.

- CO32− + H3O+ = HCO3− + H2O

- HCO3− + H3O+ = H2CO3 + H2O

- Carbonic acid cannot combine with calcium to form calcium carbonate scale. Calcium carbonate scaling tendency is estimated using the Langelier saturation index. Adding too much sulfuric acid to control carbonate scales may result in calcium sulfate, barium sulfate, or strontium sulfate scale formation on the reverse osmosis membrane.

- Prefiltration antiscalants: Scale inhibitors (also known as antiscalants) prevent formation of all scales compared to acid, which can only prevent formation of calcium carbonate and calcium phosphate scales. In addition to inhibiting carbonate and phosphate scales, antiscalants inhibit sulfate and fluoride scales and disperse colloids and metal oxides. Despite claims that antiscalants can inhibit silica formation, no concrete evidence proves that silica polymerization can be inhibited by antiscalants. Antiscalants can control acid-soluble scales at a fraction of the dosage required to control the same scale using sulfuric acid.[23]

- Some small-scale desalination units use 'beach wells'; they are usually drilled on the seashore in close vicinity to the ocean. These intake facilities are relatively simple to build and the seawater they collect is pretreated via slow filtration through the subsurface sand/seabed formations in the area of source water extraction. Raw seawater collected using beach wells is often of better quality in terms of solids, silt, oil and grease, natural organic contamination and aquatic microorganisms, compared to open seawater intakes. Sometimes, beach intakes may also yield source water of lower salinity.

High pressure pump

The high pressure pump supplies the pressure needed to push water through the membrane, even as the membrane rejects the passage of salt through it. Typical pressures for brackish water range from 1.6 to 2.6 MPa (225 to 376 psi). In the case of seawater, they range from 5.5 to 8 MPa (800 to 1,180 psi). This requires a large amount of energy. Where energy recovery is used, part of the high pressure pump's work is done by the energy recovery device, reducing the system energy inputs.

Membrane assembly

The membrane assembly consists of a pressure vessel with a membrane that allows feedwater to be pressed against it. The membrane must be strong enough to withstand whatever pressure is applied against it. Reverse-osmosis membranes are made in a variety of configurations, with the two most common configurations being spiral-wound and hollow-fiber.

Only a part of the saline feed water pumped into the membrane assembly passes through the membrane with the salt removed. The remaining "concentrate" flow passes along the saline side of the membrane to flush away the concentrated salt solution. The percentage of desalinated water produced versus the saline water feed flow is known as the "recovery ratio". This varies with the salinity of the feed water and the system design parameters: typically 20% for small seawater systems, 40% – 50% for larger seawater systems, and 80% – 85% for brackish water. The concentrate flow is at typically only 3 bar / 50 psi less than the feed pressure, and thus still carries much of the high-pressure pump input energy.

The desalinated water purity is a function of the feed water salinity, membrane selection and recovery ratio. To achieve higher purity a second pass can be added which generally requires re-pumping. Purity expressed as total dissolved solids typically varies from 100 to 400 parts per million (ppm or mg/litre)on a seawater feed. A level of 500 ppm is generally accepted as the upper limit for drinking water, while the US Food and Drug Administration classifies mineral water as water containing at least 250 ppm.

Energy recovery

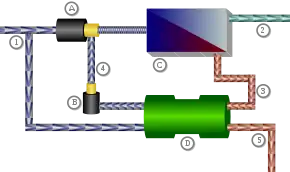

1: Sea water inflow,

2: Fresh water flow (40%),

3: Concentrate flow (60%),

4: Sea water flow (60%),

5: Concentrate (drain),

A: Pump flow (40%),

B: Circulation pump,

C: Osmosis unit with membrane,

D: Pressure exchanger

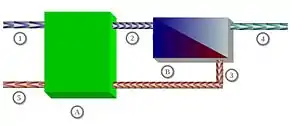

1: Sea water inflow (100%, 1 bar),

2: Sea water flow (100%, 50 bar),

3: Concentrate flow (60%, 48 bar),

4: Fresh water flow (40%, 1 bar),

5: Concentrate to drain (60%,1 bar),

A: Pressure recovery pump,

B: Osmosis unit with membrane

Energy recovery can reduce energy consumption by 50% or more. Much of the high pressure pump input energy can be recovered from the concentrate flow, and the increasing efficiency of energy recovery devices has greatly reduced the energy needs of reverse osmosis desalination. Devices used, in order of invention, are:

- Turbine or Pelton wheel: a water turbine driven by the concentrate flow, connected to the high pressure pump drive shaft to provide part of its input power. Positive displacement axial piston motors have also been used in place of turbines on smaller systems.

- Turbocharger: a water turbine driven by the concentrate flow, directly connected to a centrifugal pump which boosts the high pressure pump output pressure, reducing the pressure needed from the high pressure pump and thereby its energy input,[24] similar in construction principle to car engine turbochargers.

- Pressure exchanger: using the pressurized concentrate flow, in direct contact or via a piston, to pressurize part of the membrane feed flow to near concentrate flow pressure.[25] A boost pump then raises this pressure by typically 3 bar / 50 psi to the membrane feed pressure. This reduces flow needed from the high-pressure pump by an amount equal to the concentrate flow, typically 60%, and thereby its energy input. These are widely used on larger low-energy systems. They are capable of 3 kWh/m3 or less energy consumption.

- Energy-recovery pump: a reciprocating piston pump having the pressurized concentrate flow applied to one side of each piston to help drive the membrane feed flow from the opposite side. These are the simplest energy recovery devices to apply, combining the high pressure pump and energy recovery in a single self-regulating unit. These are widely used on smaller low-energy systems. They are capable of 3 kWh/m3 or less energy consumption.

- Batch operation: Reverse-osmosis systems run with a fixed volume of fluid (thermodynamically a closed system) do not suffer from wasted energy in the brine stream, as the energy to pressurize a virtually incompressible fluid (water) is negligible. Such systems have the potential to reach second-law efficiencies of 60%.[1][26][27]

Remineralisation and pH adjustment

The desalinated water is stabilized to protect downstream pipelines and storage, usually by adding lime or caustic soda to prevent corrosion of concrete-lined surfaces. Liming material is used to adjust pH between 6.8 and 8.1 to meet the potable water specifications, primarily for effective disinfection and for corrosion control. Remineralisation may be needed to replace minerals removed from the water by desalination, although this process has proved to be costly and not very convenient if it is intended to meet mineral demand by humans and plants. The very same mineral demand that freshwater sources provided previously. For instance water from Israel's national water carrier typically contains dissolved magnesium levels of 20 to 25 mg/liter, while water from the Ashkelon plant has no magnesium. After farmers used this water, magnesium-deficiency symptoms appeared in crops, including tomatoes, basil, and flowers, and had to be remedied by fertilization. Current Israeli drinking water standards set a minimum calcium level of 20 mg/liter. The postdesalination treatment in the Ashkelon plant uses sulfuric acid to dissolve calcite (limestone), resulting in calcium concentration of 40 to 46 mg/liter. This is still lower than the 45 to 60 mg/liter found in typical Israeli fresh water.

Disinfection

Post-treatment consists of preparing the water for distribution after filtration. Reverse osmosis is an effective barrier to pathogens, but post-treatment provides secondary protection against compromised membranes and downstream problems. Disinfection by means of ultraviolet (UV) lamps (sometimes called germicidal or bactericidal) may be employed to sterilize pathogens which bypassed the reverse-osmosis process. Chlorination or chloramination (chlorine and ammonia) protects against pathogens which may have lodged in the distribution system downstream, such as from new construction, backwash, compromised pipes, etc.[28]

Disadvantages

Household reverse-osmosis units use a lot of water because they have low back pressure. Earlier they used to recover only 5 to 15% of the water entering the system. However, the latest RO water purifiers can recover 40 to 55% of water. The remainder is discharged as wastewater. Because wastewater carries with it the rejected contaminants, methods to recover this water are not practical for household systems. Wastewater is typically connected to the house drains and will add to the load on the household septic system. A reverse-osmosis unit delivering 20 liters (5.3 U.S. gal) of treated water per day may discharge between 50 and 80 liters (13 and 21 U.S. gal) of wastewater daily. Due to this very reason, National Green Tribunal of India proposed to ban RO water purification systems in areas where the total dissolved solids (TDS) measure in water is less than 500 mg/liter[29] This has a disastrous consequence for mega cities like Delhi where large-scale use of household RO devices has increased the total water demand of the already water-parched National Capital Territory of India.[30]

Large-scale industrial/municipal systems recover typically 75% to 80% of the feed water, or as high as 90%, because they can generate the high pressure needed for higher recovery reverse osmosis filtration. On the other hand, as recovery of wastewater increases in commercial operations, effective contaminant removal rates tend to become reduced, as evidenced by product water total dissolved solids levels.

Reverse osmosis per its construction removes both harmful contaminants present in the water, as well as some desirable minerals. Modern studies on this matter have been quite shallow, citing lack of funding and interest in such study, as re-mineralization on the treatment plants today is done to prevent pipeline corrosion without going into human health aspect. They do, however link to older, more thorough studies that at one hand show some relation between long-term health effects and consumption of water low on calcium and magnesium, on the other confess that none of these older studies comply to modern standards of research.[31]

Waste-stream considerations

Depending upon the desired product, either the solvent or solute stream of reverse osmosis will be waste. For food concentration applications, the concentrated solute stream is the product and the solvent stream is waste. For water treatment applications, the solvent stream is purified water and the solute stream is concentrated waste.[32] The solvent waste stream from food processing may be used as reclaimed water, but there may be fewer options for disposal of a concentrated waste solute stream. Ships may use marine dumping and coastal desalination plants typically use marine outfalls. Landlocked reverse osmosis plants may require evaporation ponds or injection wells to avoid polluting groundwater or surface runoff.[33]

New developments

Since the 1970s, prefiltration of high-fouling waters with another larger-pore membrane, with less hydraulic energy requirement, has been evaluated and sometimes used. However, this means that the water passes through two membranes and is often repressurized, which requires more energy to be put into the system, and thus increases the cost.

Other recent developmental work has focused on integrating reverse osmosis with electrodialysis to improve recovery of valuable deionized products, or to minimize the volume of concentrate requiring discharge or disposal.

In the last few years, many domestic RO water purifier companies have begun finding solution to this problem. The most promising solution amongst these appears to be LPHR. LPHR, or low-pressure high-recovery multistage RO process produces a very concentrated brine and freshwater at the same time. More importantly, it was found to be economically feasible for a water recovery of more than 70% with an OPD between 58 and 65 bar to produce a freshwater product containing no more than 350 ppm TDS from a seawater feed with 35,000 ppm TDS.[34]

In the production of drinking water, the latest developments include nanoscale and graphene membranes.[35]

The world's largest RO desalination plant was built in Sorek, Israel, in 2013. It has an output of 624 thousand cubic metres per day (165 million US gallons per day).[36]

See also

- Electrodeionization

- ERDLator

- Forward osmosis

- Microfiltration

- Reverse osmosis plant

- Richard Stover, pioneered the development of an energy-recovery device currently in use in most seawater reverse-osmosis desalination plants

- Silt density index

- Salinity gradient

- Milli-Q water

- Water pollution

- Water quality

References

- Warsinger, David M.; Tow, Emily W.; Nayar, Kishor G.; Maswadeh, Laith A.; Lienhard V, John H. (2016). "Energy efficiency of batch and semi-batch (CCRO) reverse osmosis desalination". Water Research. 106: 272–282. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2016.09.029. hdl:1721.1/105441. PMID 27728821.

- Crittenden, John; Trussell, Rhodes; Hand, David; Howe, Kerry and Tchobanoglous, George (2005). Water Treatment Principles and Design, 2nd ed. John Wiley and Sons. New Jersey. ISBN 0-471-11018-3

- Panagopoulos, Argyris; Haralambous, Katherine-Joanne; Loizidou, Maria (25 November 2019). "Desalination brine disposal methods and treatment technologies – A review". Science of the Total Environment. 693: 133545. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.693m3545P. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.351. ISSN 0048-9697. PMID 31374511.

- Glater, J. (1998). "The early history of reverse osmosis membrane development". Desalination. 117 (1–3): 297–309. doi:10.1016/S0011-9164(98)00122-2.

- Weintraub, Bob (December 2001). "Sidney Loeb, Co-Inventor of Practical Reverse Osmosis". Bulletin of the Israel Chemical Society (8): 8–9.

- Cadotte, John E. (1981) "Interfacially synthesized reverse osmosis membrane" U.S. Patent 4,277,344

- Jones, Edward; et al. (20 March 2019). "The state of desalination and brine production: A global outlook". Science of the Total Environment. 657: 1343–1356. Bibcode:2019ScTEn.657.1343J. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.12.076. PMID 30677901.

- 2012 Annual Consumer Report on the Quality of Tap Water. City of Cape Coral

- Lachish, Uri. "Optimizing the Efficiency of Reverse Osmosis Seawater Desalination". guma science.

- Knorr, Erik Voigt, Henry Jaeger, Dietrich (2012). Securing Safe Water Supplies : comparison of applicable technologies (Online-Ausg. ed.). Oxford: Academic Press. p. 33. ISBN 978-0124058866.

- Council Directive of 15 July 1980 on the approximation of the laws of the Member States relating to the exploitation and marketing of natural mineral waters. eur-lex.europa.eu

- "Purification of Contaminated Water with Reverse Osmosis" ISSN 2250-2459, ISO 9001:2008 Certified Journal, Volume 3, Issue 12, December 2013

- "Award-winning Solar Powered Desalination Unit aims to solve Central Australian water problems". University of Wollongong. 4 November 2005. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- Low temperature desalination using solar collectors augmented by thermal energy storage

- Shah, Vishal, ed. (2008). Emerging Environmental Technologies. Dordrecht: Springer Science. p. 108. ISBN 978-1402087868.

- Grabowski, Andrej (2010). Electromembrane desalination processes for production of low conductivity water. Berlin: Logos-Verl. ISBN 978-3832527143.

- Lewis, Michael J; Young, Tom W (6 December 2012). Brewing (2 ed.). New York: Kluwer. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-4615-0729-1.

- Warsinger, David M.; Mistry, Karan H.; Nayar, Kishor G.; Chung, Hyung Won; Lienhard V, John H. (2015). "Entropy Generation of Desalination Powered by Variable Temperature Waste Heat". Entropy. 17 (11): 7530–7566. Bibcode:2015Entrp..17.7530W. doi:10.3390/e17117530.

- International Desalination Association Yearbook 2012–13

- Israel is No. 5 on Top 10 Cleantech List in Israel 21c A Focus Beyond Archived 16 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 21 December 2009

- Desalination Plant Seawater Reverse Osmosis (SWRO) Plant. Water-technology.net

- Sauvetgoichon, B (2007). "Ashkelon desalination plant — A successful challenge". Desalination. 203 (1–3): 75–81. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2006.03.525.

- Malki, M. (2008). "Optimizing scale inhibition costs in reverse osmosis desalination plants". International Desalination and Water Reuse Quarterly. 17 (4): 28–29.

- Yu, Yi-Hsiang; Jenne, Dale (8 November 2018). "Numerical Modeling and Dynamic Analysis of a Wave-Powered Reverse-Osmosis System". Journal of Marine Science and Engineering. MDPI AG. 6 (4): 132. doi:10.3390/jmse6040132. ISSN 2077-1312.

- Stover, Richard L. (2007). "Seawater reverse osmosis with isobaric energy recovery devices". Desalination. Elsevier BV. 203 (1–3): 168–175. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2006.03.528. ISSN 0011-9164.

- Cordoba, Sandra; Das, Abhimanyu; Leon, Jorge; Garcia, Jose M; Warsinger, David M (2021). "Double-acting batch reverse osmosis configuration for best-in-class efficiency and low downtime". Desalination. Elsevier BV. 506: 114959. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2021.114959. ISSN 0011-9164.

- Wei, Quantum J.; Tucker, Carson I.; Wu, Priscilla J.; Trueworthy, Ali M.; Tow, Emily W.; Lienhard, John H. (2020). "Impact of salt retention on true batch reverse osmosis energy consumption: Experiments and model validation". Desalination. Elsevier BV. 479: 114177. doi:10.1016/j.desal.2019.114177. hdl:1721.1/124221. ISSN 0011-9164.

- Sekar, Chandru. "IEEE R10 HTA Portable Autonomous Water Purification System". IEEE. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- "RO Water Purifier Banned in India". India: Deccan Herald. 10 February 2020. OCLC 185061134. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Singh, Govind (2017). "Implication of Household Use of R.O. Devices for Delhi's Urban Water Scenario". Journal of Innovation for Inclusive Development. 2 (1): 24–29.

- Kozisek, Frantisek. "Health risks from drinking demineralised water" (PDF). Czech Republic: National Institute of Public Health. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 February 2022.

- Weber, Walter J. (1972). Physicochemical Processes for Water Quality Control. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 320. ISBN 9780471924357. OCLC 1086963937.

- Hammer, Mark J. (1975). Water and Waste-Water Technology. New York: John Wiley & Sons. p. 266. ISBN 9780471347262.

- M. GöktuğAhunbay (2019). "Achieving high water recovery at low pressure in reverse osmosis processes for seawater desalination". ScienceDirect. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Zhu, Chongqin; Li, Hui; Zeng, Xiao Cheng; Wang, E. G.; Meng, Sheng (2013). "Quantized Water Transport: Ideal Desalination through Graphyne-4 Membrane". Scientific Reports. 3: 3163. arXiv:1307.0208. Bibcode:2013NatSR...3E3163Z. doi:10.1038/srep03163. PMC 3819615. PMID 24196437.

- "Next Big Future: Israel scales up Reverse Osmosis Desalination to slash costs with a fourth of the piping". nextbigfuture.com. 19 February 2015.

Sources

- Metcalf; Eddy (1972). Wastewater Engineering. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company.