Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral

Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral (Irish: Ardeaglais Naomh Fionnbarra) is a Gothic Revival three-spire Church of Ireland cathedral in the city of Cork. It is located on the south bank of the River Lee and dedicated to Finbarr of Cork, patron saint of the city. Formerly the sole cathedral of the Diocese of Cork, it is now one of three co-cathedrals in the United Dioceses of Cork, Cloyne and Ross in the ecclesiastical province of Dublin. Christian use of the site dates back 7th-century AD when, according to local lore, Finbarr of Cork founded a monastery. The original building survived until the 12th century, when it either fell into disuse or was destroyed during the Norman invasion of Ireland. Around 1536, during the Protestant Reformation, the cathedral became part of the established church, later known as the Church of Ireland. The previous building was constructed in the 1730s, but was widely regarded as plain and featureless.

| Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork | |

|---|---|

| Cathedral Church of Saint Fin Barre | |

Ardeaglais Naomh Fionnbarra | |

West façade | |

Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork | |

| 51.8944°N 08.4806°W | |

| Location | Bishop Street, Cork, T12 K710 |

| Country | Ireland |

| Denomination | Church of Ireland |

| Website | cathedral |

| History | |

| Dedication | Fin Barre of Cork |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | William Burges |

| Style | Gothic Revival |

| Groundbreaking | 1865 |

| Completed | 1879 |

| Specifications | |

| Bells | 13 (1870, reinstalled 2008) |

| Administration | |

| Province | Dublin |

| Diocese | Cork, Cloyne and Ross |

| Clergy | |

| Bishop(s) | Paul Colton |

| Dean | Nigel Dunne |

| Precentor | The Dean of Cloyne |

| Chancellor | The Dean of Ross |

| Archdeacon | Adrian Wilkinson |

| Laity | |

| Director of music | Peter Stobart |

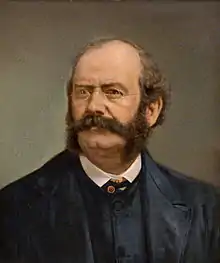

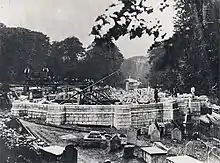

The cathedral's demolition and rebuild was commissioned in the mid-19th century by an Anglican church intent on strengthening its hand after the reforms of penal law. Work began in 1863, and resulted in the first major commissioned project for the Victorian architect William Burges, who designed most of the cathedral's architecture, sculpture, stained glass, mosaics and interior furniture. Saint Fin Barre's foundation stone was laid in 1865. The cathedral was consecrated in 1870 and the limestone spires completed by October 1879.

Saint Fin Barre's is mostly built from local stone sourced from Little Island and Fermoy. The exterior is capped by three spires: two on the west front and above where the transept crosses the nave. Many of the external sculptures, including the gargoyles, were modelled by Thomas Nicholls.[1] The entrances contain the figures of over a dozen biblical figures, capped by a tympanum showing a Resurrection scene.

History

Finbarr of Cork

The church grounds are south of the River Lee on Holy Island, on one of the many inlets forming the Great Marsh of Munster (Corcach Mor na Mumhan). Saint Fin Barre's is on the site of at least two previous church buildings, each dedicated to Fin Barre of Cork, patron saint of Cork city and founder of the monastic hermitage at Gougane Barra.[2]

Finbarr was born in about 550. He was, by legend, given Gougane Barra as a place of contemplation, and visited Cork city to lay the foundation stones for the "one true Christian faith".[3] According to tradition, after Finbarr died his remains were brought to Cork to be enclosed in a shrine near the site of today's cathedral.[4]

Archaeological evidence suggests the first site at Fin Barre's probably dates from the 7th century, and consisted of a church and round tower[5] that survived until the 12th century, after which it fell into neglect, or was destroyed during the Norman invasions.[6]

Medieval and 18th-century churches

A 1644 reference to the site notes that "in one of the suburbs of Korq [Cork] there is an old tower ten or twelve feet [3.3 m] in circumference, and more than one hundred feet [30 m] high ... believ[ed] to have been built by St. Baril [Finbarr]".[7] The building was badly damaged in 1690 during the siege of Cork, after which only the steeple remained intact, due to an outbreak of fire and the impact of a 24-pound (11-kg) shot[8] from Elizabeth Fort in nearby Barrack Street. The cannonball was rediscovered during the 1865 demolition and is now on display in the cathedral.[9] The church was demolished in 1735[10] and replaced the same year by a smaller building, as part of a citywide phase of construction and renovation.[11]

Only the earlier spire was retained for the new building.[12] The older part of this church was described in 1862 as Doric in style, attached to a featureless modern tower with an "ill-formed" spire.[13] The building was widely considered to be poorly designed. The Dublin Builder called it "a shabby apology for a cathedral which has long disgraced Cork",[14] while The Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland judged it "a plain, massive, dull, tasteless, oblong pile, totally destitute of what is usually regarded as cathedral character, and possessing hardly a claim to any sort of architectural consideration".[15] It was demolished in 1865.[16]

19th-century building

In April 1862, the Church of Ireland, in pursuit of a larger, more attractive cathedral, and determined to reassert its authority in response to resurgent Catholicism,[17] initiated a competition for a replacement building,[18] which became the commission for the first cathedral to be built in the British Isles since London's St Paul's.[18] The next February, the designs of the architect William Burges, then 35,[19] were declared the winner of the competition.[20] Burges disregarded the £15,000 budget, producing a design that he estimated would cost twice as much.[18] Despite the protestations of fellow competitors, it won.[21] His diary records his reaction—"Got Cork!"—while cathedral accounts mention a payment of £100 as prize money.[20] The foundation stone was laid on 12 January 1865,[18] the unfinished cathedral consecrated in 1870 by Bishop John Gregg,[20] and the spires topped out in 1879,[21] though minor work continued on the cathedral for many years afterward.[22]

Burges used a number of his earlier unrealised designs for the exterior, including those intended for the Crimea Memorial Church, Istanbul, St John's Cathedral, Brisbane and elevations for Lille Cathedral.[23] The main obstacle was economics. Despite the efforts of fundraisers, Cork was unable to afford a large cathedral.[24] Burges partially alleviated this by designing a three-spired exterior that enhanced the size of the building to viewers.[24] He realised early on the build would vastly exceed the money the city had raised.[14]

The superiority of his design was recognised by Gregg, who supported Burges and lobbied for additional funding.[25] Gregg was instrumental in sourcing additional money, including local merchants such as William Crawford of the Crawford brewing family and Francis Wise, a local distiller.[8] The final total was significantly over £100,000. Assured by Gregg's efforts, Burges was unconcerned.[26] Gregg died before the completion of the project. In his place, his son Robert continued his father's support, and in 1879 ceremoniously placed the final stone on the eastern spire. By then the contractors estimated that the build was nearing its completion, with only a number of pre-designed stained glass fittings left to be installed.[18]

[In the future] the whole affair will be on its trial and, the elements of time and cost being forgotten, the result only will be looked at. The great questions will then be, first, is this work beautiful and, secondly, have those to whom it was entrusted, done it with all their heart and all their ability.[26]

January 1877 letter from Burges to Gregg

The cathedral holds the book of estimates prepared for the decoration of the west front. Nicholls was paid £1,769 for the modelling, and Robert McLeod £5,153 for the carving. Burges took 10 per cent for the design, more than his usual 5 per cent, apparently due to his high level of personal involvement.[27] Its construction took seven years before the first service was held in 1870. During the first building phase, three firms of contractors were employed, owned by, chronologically, Robert Walker, Gilbert Cockburn and John Delany, who completed the spires' construction in 1879.[8] Building, carving and decoration continued into the 20th century, long after Burges's death in 1881,[20] including the marble panelling of the aisles, the installation of the reredos and side choir walls, and the 1915 construction of the chapter house.[28]

The architectural historians David Lawrence and Ann Wilson call Saint Fin Barre's "undoubtedly [Burges's] greatest work in ecclesiastical architecture",[20] with an "overwhelming and intoxicating" interior.[29] Through his ability, careful leadership of his team, artistic control, and by vastly exceeding the intended budget, Burges produced a building that—though not much larger than a parish church—has been called "a cathedral becoming such a city and one which posterity may regard as a monument to the Almighty's praise".[30]

20th and 21st centuries

Mindful that the cathedral was unlikely to be finished in his lifetime, Burges produced comprehensive plans for its decoration and furnishing, recorded in his Book of Furniture and Book of Designs.[31] At the end of the 20th century, a major restoration of the cathedral, costing £5 million, was undertaken.[32] This included the reinstatement and restoration of the twin trumpets held by the resurrection angel which had been vandalised in 1999.[32] The restoration programme also saw the cleaning, repointing and repair of the exterior of the building, including the re-carving of some of Burges's gargoyles, where repair proved impracticable.[33] The cathedral's heating system was also replaced when it was found to be damaging the intricate mosaic floor.[34]

In 2006, Lawrence and Wilson published the first detailed study of the cathedral's history and architecture, The Cathedral of Saint Fin Barre at Cork: William Burges in Ireland.[35] The building is also covered in Frank Keohane's volume Cork: City and County, in the Buildings of Ireland series, published in 2020.[36] The cathedral is one of the three cathedrals of the Anglican Diocese of Cork, Cloyne and Ross, the other two being Saint Colmán's Cathedral in Cloyne, and Saint Fachtna's Cathedral in Rosscarbery.[37]

Notable interments in the graveyard include those of archbishop William Lyon (died 1617), Richard Boyle (died 1644),[38] and, in a family vault, the first "Lady Freemason", Elizabeth Aldworth (died c. 1773–1775).[39]

Exterior

Architecture

The cathedral's style is Gothic Revival, Burges's preferred period, which he used for his own home, The Tower House, in London. He reused elements of unsuccessful designs he had produced for competitions for cathedrals at Lille and Brisbane.[40] The shell of the building is mostly limestone, sourced from near Cork, with the interior walls formed from stone brought from Bath. The red marble came from Little Island, the purple-brown stone from Fermoy.[8]

Each of the three spires supports a Celtic cross, a reference to Saint Patrick, seen as a foundational ancestor by both Irish Catholics and Protestants. This inclusion was an implicit statement of national identity, but was against Burges's wishes. His initial design included weather vanes, a choice rejected by the building committee, which, according to the historian Antóin O'Callaghan, wanted the church to "retain the continuity with the one true faith of the ancient past".[41]

The northwestern tower hosts a ring of twelve bells, as well as an additional sharp second bell, which forms part of a diatonic ring of eight bells, for a total of 13 bells.[22][42] Originally, eight bells were hung on a wooden frame in the tower in either 1752 or 1753, which were cast by Abel Rudman of Gloucester.[42][43] The bells were taken down in 1865 in advance of the original cathedral's demolition. They were reinstated at some point before the new cathedral's consecration in 1870. But at this point, the towers and spires had not been constructed above the level of the nave, and consequently the bells were hung lower than is appropriate, which meant that they could not be rung properly. In 1902, an appeal was launched in an attempt to raise £500 to properly fit the bells, and the next year they were hung from a steel frame higher in the cathedral.[44] Due to corrosion of the frame in 2007, the frame was replaced, which created an opportunity to expand on the collection of bells: in 2008 four trebles were added, along with the additional second bell.[42][43] Between their initial installation and today, many of the bells have been recast, and all were restored in 2008.[42][44]

The spires had a troubled construction: it was a difficult build technically and thus expensive to fund. The cost reached £40,000 early in the build, with a further £60,000 spent by the time the spires were in place. Along the way, a number of sub-contractors were hired and dismissed; the contract was eventually completed by the Cork builder John Delaney, hired in May 1876. By the end of the next year the main and two ancillary spires were complete.[25]

Sculpture

An 1881 estimate by the local stonemason McLeod suggests that Burges provided around 844 sculptures, of which around 412 were for the interior.[28] The total of some 1,260 sculptures include 32 gargoyles, each with different animal heads.[45] Burges oversaw nearly all aspects of the design, headquartered in his office in Buckingham Street and on numerous site visits. Most modern scholars agree that his overarching control over the design of the architecture, statuary, stained glass and internal decorations led to the cathedral's unity of style.[8] He considered sculpture an "indispensable attribute of architectural effect"[46] and, at Saint Fin Barre's, believed he was engaged upon "a work which has not been attempted since the West front of Wells Cathedral".[46] In the designs for the pieces decorating the cathedral, Burges worked closely with Thomas Nicholls, who constructed each figure in plaster,[46] and with McLeod and local stonemasons, who carved almost all of the sculptures in situ.[46]

Burges's designs for the western façade were based on medieval French iconography. He considered this front to be the most important exterior feature, as it would be lit by the setting sun and thus the most dramatic.[47] The theme is The Last Judgement, with representations of the twelve Apostles bearing instruments of their martyrdom, the Wise and the Foolish Virgins, the Resurrection of the Dead and the Beasts of The Evangelists.[48] The gilded copper "resurrection angel" facing eastward on the main spire is locally the cathedral's most iconic feature, and colloquially known as the "goldie angel".[32] It was designed by Burges and erected in 1870 free of charge as his gift to the city, in recognition of Cork's willingness to fund his original design, and positioned in place of an intended wrought-iron cross.[41]

.JPG.webp)

The imagery of the tympanum is taken from the Book of Revelation, with the divine on the upper register and mortals below. It shows an angel, accompanied by John the Evangelist, measuring the temple in Jerusalem, while beneath them the dead rise from their graves.[25] Of these sculptures, the Victorian critic Charles Eastlake wrote in A History of the Gothic Revival, "no finer examples of decorative sculpture have been produced during the Revival".[1]

Burges found it difficult to realise some of his original images for the sculptures and stained glass panels; a number of them contained frontal nudes, including the designs for the creation of the planets, the figures of Adam and Eve, Christ in Glory, Our Lord as King Crucified, the dead rising from their graves, and the welcoming angels.[49] In August 1868, some Protestant committee members, led by the chancellor, George Webster, rejected the use of images of the naked human body in ecclesiastical iconography, especially in images of Christ, and forced Burges to provide clothed designs, modesty-providing loincloths, or strategically placed foliage or books.[25] In frustration Burges wrote, "I am sorry to see Puritanism so rampant in Cork ... I wish we could transplant the building to England".[47] His revised designs were reviewed in April and May 1869, but again rejected. Both Gregg and the dean, Arthur Edwards, supported Burges, and moved the decision from the general committee to a select vestry sub-committee. Webster continued to object, but the modified designs were finally approved.[47]

.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)

.JPG.webp)

Interior

Plan and elevation

The cathedral's plan is conventional; the west front is opened by three entrance doors leading to the nave, with internal vaulting, arcade, triforium and clerestory, rising to a timber roof. Beyond the nave, the pulpit, choir, bishop's throne and altar end in an ambulatory.[51] The small floor plan drew criticism both at the time and in later years. The building is relatively short at 180 feet, but contains all of the traditional elements of a larger cathedral. A contemporary critic, Robert Rolt Brash, wrote, "the effect of this is to make the building look exceedingly short, and disproportionately high".[51] Although modest in size, the compact design makes the most of the small footprint. The three spires allow the illusion of greater interior space.[52]

Main features

Burges designed most of the interior, including the mosaic pavement, the altar, the pulpit and bishop's throne.[52][53] The narrow and unusually high marble nave, from red and puce stone, is supported by large columns supporting the central tower and spire. The exterior gives the impression of a large structure, which is at odds with the reduced size of the interior, where the choir, sanctuary and ambulatory take up almost half of the floor space.[54] The interior is filled with colour, most especially from the stained glass windows. This aspect of the interior is in marked contrast to the uniform and austere grey exterior.[54]

The cylindrical pulpit is near the entrance and was completed in 1874, but not painted until 1935. Like the baptismal font, it is placed on four sculpted legs. It contains five stone relief figures, assumed to be the four evangelists, and Paul the Apostle sitting on an upturned "pagan" altar, and a winged dragon below the reading stand.[28] The baptismal font is near the entrance. Its ledge is decorated with a carving of the head of John the Baptist. The font's bowl is of Cork red marble,[55] and supported by a stem, also red marble, a marble shaft of sculpted capitals, and an octagonal base.[56] Brass lettering reads "We are buried with Him by baptism into death".[55]

The lectern (reading desk) is made of solid brass, from a design Burges originally intended for Lille Cathedral. It is decorated with the heads of Moses and King David.[55] There is a "Heroes Column" (War Memorial) by the Choir, at the Dean's chapel. It contains the names of 400 men from the dioceses killed in battle during the First World War. A processional cross, completed in 1974 by Patrick Pye, is in front of the Dean's chapel. The 46-foot 'Great Oak Throne' of the Cork Dioceses Bishop was installed in 1878, alongside a statue of Fin Barre of Cork and a kneeling angel.[28]

Stained glass

Burges conceived the iconographical scheme for the stained glass windows, designed the individual panels for the each of the 74 windows, and oversaw every stage of their production. According to Maurice Carey, "in consequence, the windows have a consistent cohesive style and follow a logical sequence in subject matter".[54] The panels were cartooned by H. W. Lonsdale and manufactured in London between 1868 and 1869 by William Gualbert Saunders, who worked in Burges's office before forming his own firm of stained glass makers.[19][57] Doctrinal objections to some of the figures, particularly of Christ, lead to a four-year delay, with their eventual installation between 1873 and 1881. Four windows remain incomplete.[58] Lonsdale's cartoons are kept at the cathedral.[58]

The impact created by all these glowing, coloured religious images is overwhelming and intoxicating. To enter St Fin Barre's Cathedral is an experience unparalleled in Ireland and rarely matched anywhere.

—David Lawrence writing on the stained glass windows of Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral[29]

Many of the figures relate to Christian iconography, and echo those in the tympanum, including, in the ambulatory a window showing God as the King of Heaven overlooking the evangelists Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. In the panel, Matthew takes human form, Mark is depicted as a lion, Luke as an ox, while John takes the form of an eagle.[52] As elsewhere in the cathedral, the illustrations can be divided between the divine, wise and foolish.[57]

The scheme begins and ends with two rose windows, at the west front and south transept respectively.[59] The west rose window shows God as the creator resting on a rainbow and in the act of blessing. He is surrounded by eight compartments, each inspired by the scenes from Book of Genesis, beginning with the creation of light, and ending with the birth of Eve, and Adam naming the animals. [60] The south transept rose window, known as the "Heavenly Hierarchies", places Christ the King in the centre, with the compartments containing a series of angels, archangels and cherubim. Separate glass sheets containing building tools are placed between each angelic compartment.[59]

The nave windows contain signs of the Zodiac. Each lancet by the arcade contains a grisaille panel. These scenes are mostly from the Old Testament, while those from the transepts onward are of prophets who foretold Christ's coming, or from the New Testament.[58] The clerestory panels above the high altar depict Christ reigning from his cross alongside His Mother, John, the Three Marys and various disciples. The windows around the ambulatory include scenes from the Life of Christ, culminating in a representation of heaven at worship from the Book of Revelation.[54]

Pipe organ

The organ was built in 1870 by William Hill & Sons. It consisted of three manuals, over 4,500 pipes and 40 stops.[61] The main organ utilised a tubular-pneumatic action, with tracker action for the other two manuals. It was in place for the cathedral's grand opening on Saint Andrew's Day, 1870, and positioned in the west gallery, but moved to the north transept in 1889, to improve acoustics, maximise space, and avoid its interference with the view of the windows.[62] That year, a 14-foot pit was dug in the floor beside the nave, as the new location for the organ.[11]

Its maintenance has been one of the most expensive parts of the cathedral's upkeep.[11] It was overhauled in 1889 by the Cork firm T.W. Magahy, which added three new stops. The organ was moved from the west gallery (balcony) down to a pit in the north transept, where it sits today.[63] Most of the choir organ is housed in an enclosure attached to the console, the lid of which the organist can raise or lower electrically.[64] The next major overhaul was in 1906 by Hele & Company of Plymouth, which added a fourth manual (the Solo). By this stage, the action of the organ was entirely pneumatic. In 1965–1966, J. W. Walker & Sons Ltd of London overhauled the soundboards, installed a new console with electropneumatic action, and lowered the pitch.[65]

By 2010 the organ's electrics were unreliable. Trevor Crowe was employed to reconstruct and increase the number of pipes,[66] and make tonal enhancements, including a 32′ extension to the pedal trombone.[67] The project cost €1.2m and took three years to complete.[66]

References

Notes

- Eastlake 1872, p. 354.

- Farmer 2011, p. 165.

- Caulfield 1871, p. v.

- Cahalane, P. (1953). "Saint Finnbarr, Founder of the Diocese of Cork". The Fold.

- Bracken & Riain-Raedel 2006, p. 47.

- Caulfield 1871, p. vi.

- Caulfield 1871, p. viii.

- Burgess 2002.

- Caulfield 1871, p. x.

- Day & Patton 1932, p. 133.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 60.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 55.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 153.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, p. 28.

- The Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland 1846, p. 522.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 155.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, p. 41.

- Crook 2013, p. 160.

- Williams 2004, p. 6.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, p. 19.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, p. 35.

- St Leger 2013, p. 357.

- Crook 1981, p. 199.

- Crook 1981, p. 200.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 160.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, ch. "Preface".

- Crook 1981, p. 95.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 161.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, p. 110.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, p. 37.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, p. 151.

- Hogan, Dick (17 February 1999). "Cork's Landmark Angel Restored to Its Former Glory". The Irish Times. Dublin. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- "St. Fin Barre's Cathedral". RBR Conservation. 20 January 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- Burgess 2002, p. 7.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, pp. 15–18.

- Keohane 2020, pp. 143–150.

- St Leger, Alicia. "A Short History of the Diocese". Cork: United Diocese of Cork, Cloyne and Ross. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- Ware, James. "The Antiquities and History of Ireland". Dublin: A. Crook, 1705. p. 36

- Speth 1895, p. 55.

- Turnor 1950, p. 70.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 162.

- "The Bells of St Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork". Cork Anglican. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Roche, Barry (27 March 2008). "Sound move by St Fin Barre's as historic bells refurbished". The Irish Times. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

- "Bells". Cork Cathedral. Retrieved 30 August 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Carey 2015, p. 15.

- Crook 2013, p. 167.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 159.

- Lawrence & Wilson 2006, p. 113.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 158.

- Carey 2015, p. 11.

- Crook 2013, p. 164.

- Banerjee, Jacqueline (2009). "St. Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork, by William Burges". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 30 June 2017.

- Crook 2013, pp. 172–176.

- Carey 2015, p. 17.

- Carey 2015, p. 19.

- O'Callaghan 2016, p. 157.

- Banerjee, Jacqueline (2015) [2006]. "The Interior of St. Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork, by William Burges". The Victorian Web. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Cronin 2013, p. 7.

- Cronin 2013, p. 96.

- Cronin 2013, p. 11.

- "The Cathedral Organ". Cork: Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral. Archived from the original on 17 April 2017.

- Carey 2015, p. 24.

- Leland, Mary (15 May 2005). "Breathing New Life into Cork's Vital Organs". Irish Independent. Dublin: Independent News & Media. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Kelleher, Olivia (21 October 2013). "4,500-Pipe Organ Back to Heavenly Duty after Restoration". Irish Independent. Dublin: Independent News & Media. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- Leland, Mary (6 September 2007). "An Irishwoman's Diary". The Irish Times. Dublin. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- "Deenihan Attends St Fin Barre's Cathedral following Major Restoration Works" (Press release). Dublin: Irish Government Information Services. 20 October 2013. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- English, Eoin (3 September 2010). "Iconic Cathedral Organ to 'Speak Again'". Irish Examiner. Cork. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

Sources

- Bracken, Damian; Riain-Raedel, Dagmar Ó (2006). Ireland and Europe in the Twelfth Century: Reform and Renewal. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-85182-848-7.

- Burgess, John (12 November 2002). Maintenance of a Masterpiece: St Fin Barres Cathedral, Cork (PDF). Joint Meeting of the Cork Region IEI and CIBSE. Cork: Rochestown Park Hotel. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Carey, Maurice (2015). Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral. Cork: Jarrold. ISBN 978-0-7117-2954-4.

- Caulfield, Richard (1871). Annals of St. Fin Barre's Cathedral, Cork: Compiled from Records in the British Museum; the Bodleian Library, Oxford; the Public Record Office, London; the Chapter Book of the Cathedral; the Council Books of the Corporation of Cork; and Other Authentic Sources. Cork: Purcell & Company.

- Cronin, Eileen (2013). A Guide to the Stained Glass Windows of Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral Cork. Cork: Saint Fin Barre's Cathedral. OCLC 891574691.

- Crook, J. Mordaunt (1981). The Strange Genius of William Burges. Cardiff: The National Museum of Wales. ISBN 978-0-7200-0259-1.

- ——— (2013). William Burges and the High Victorian Dream. London: Frances Lincoln. ISBN 978-0-7112-3349-2.

- Day, J. Godfrey F.; Patton, Henry E. (1932). The Cathedrals of the Church of Ireland. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Eastlake, Charles L. (1872). A History of the Gothic Revival: An Attempt to Show How the Taste for Mediæval Architecture which Lingered in England during the Two Last Centuries Has since Been Encouraged and Developed. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. OCLC 1026953. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- Farmer, David (2011). The Oxford Dictionary of Saints (rev. 5th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780199596607.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-1995-9660-7.

- Keohane, Frank (2020). Cork: City and County. Buildings of Ireland. New Haven, US and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-22487-0.

- Lawrence, David; Wilson, Ann (2006). The Cathedral of Saint Fin Barre at Cork: William Burges in Ireland. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-023-6.

- O'Callaghan, Antóin (2016). The Churches of Cork City. Dublin: The History Press Ireland. ISBN 978-1-845-88893-0.

- Speth, G. W., ed. (1895). Ars Quatuor Coronatorum: Being the Transactions of the Quatuor Coronati Lodge No. 2076, London. Vol. 8. London: W. J. Parre H. Retrieved 31 March 2018.

- St Leger, Dr. Alicia (2013). "The Province of Dublin: Cork, Cloyne and Ross". In McAuley, Alicia; Costecalde, Dr. Claude; Walker, Prof Brian (eds.). The Church of Ireland: An illustrated history. Dublin: Booklink. p. 357. ISBN 978 1 906886 56 1.

- The Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland: Adapted to the New Poor-Law, Franchise, Municipal and Ecclesiastical Arrangements, and Compiled with a Special Reference to the Lines of Railroad and Canal Communication, as Existing in 1844–45. Vol. 1. Glasgow: A. Fullarton and Company. 1846. Retrieved 1 April 2018.

- Turnor, Reginald (1950). Nineteenth Century Architecture in Britain. London: R. T. Batsford. OCLC 3978928.

- Williams, Matthew (2004). William Burges. Gloucestershire: Pitkin. ISBN 978-1-84165-139-2.