Scottish clan

A Scottish clan (from Gaelic clann, literally 'children', more broadly 'kindred'[1]) is a kinship group among the Scottish people. Clans give a sense of shared identity and descent to members, and in modern times have an official structure recognised by the Court of the Lord Lyon, which regulates Scottish heraldry and coats of arms. Most clans have their own tartan patterns, usually dating from the 19th century, which members may incorporate into kilts or other clothing.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Scotland |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Mythology and Folklore:Category:Scottish folklore |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

The modern image of clans, each with their own tartan and specific land, was promulgated by the Scottish author Sir Walter Scott after influence by others. Historically, tartan designs were associated with Lowland and Highland districts whose weavers tended to produce cloth patterns favoured in those districts. By process of social evolution, it followed that the clans/families prominent in a particular district would wear the tartan of that district, and it was but a short step for that community to become identified by it.

Many clans have their own clan chief; those that do not are known as armigerous clans. Clans generally identify with geographical areas originally controlled by their founders, sometimes with an ancestral castle and clan gatherings, which form a regular part of the social scene. The most notable clan event of recent times was The Gathering 2009 in Edinburgh, which attracted at least 47,000 participants from around the world.[2]

It is a common misconception that every person who bears a clan's name is a lineal descendant of the chiefs.[3] Many clansmen, although not related to the chief, took the chief's surname as their own either to show solidarity or to obtain basic protection or for much needed sustenance.[3] Most of the followers of the clan were tenants, who supplied labour to the clan leaders.[4] Contrary to popular belief, the ordinary clansmen rarely had any blood tie of kinship with the clan chiefs, but they sometimes took the chief's surname as their own when surnames came into common use in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[4] Thus, by the eighteenth century the myth had arisen that the whole clan was descended from one ancestor, perhaps relying on Scottish Gaelic clann originally having a primary sense of 'children' or 'offspring'.[4]

Clan organisation

Clan membership

As noted above, the word clan is derived from the Gaelic word clann.[5] However, the need for proved descent from a common ancestor related to the chiefly house is too restrictive.[6] Clans developed a territory based on the native men who came to accept the authority of the dominant group in the vicinity.[6] A clan also included a large group of loosely related septs – dependent families – all of whom looked to the clan chief as their head and their protector.[7]

.jpg.webp)

According to the former Lord Lyon, Sir Thomas Innes of Learney, a clan is a community that is distinguished by heraldry and recognised by the Sovereign. Learney considered clans to be a "noble incorporation" because the arms borne by a clan chief are granted or otherwise recognised by the Lord Lyon as an officer of the Crown, thus conferring royal recognition to the entire clan. Clans with recognised chiefs are therefore considered a noble community under Scots law. A group without a chief recognised by the Sovereign, through the Lord Lyon, has no official standing under Scottish law. Claimants to the title of chief are expected to be recognised by the Lord Lyon as the rightful heir to the undifferenced arms of the ancestor of the clan of which the claimant seeks to be recognized as chief. A chief of a clan is the only person who is entitled to bear the undifferenced arms of the ancestral founder of the clan. The clan is considered to be the chief's heritable estate and the chief's Seal of Arms is the seal of the clan as a "noble corporation". Under Scots law, the chief is recognised as the head of the clan and serves as the lawful representative of the clan community.[8][9]

Historically, a clan was made up of everyone who lived on the chief's territory, or on territory of those who owed allegiance to the said chief. Through time, with the constant changes of "clan boundaries", migration or regime changes, clans would be made up of large numbers of members who were unrelated and who bore different surnames. Often, those living on a chief's lands would, over time, adopt the clan surname. A chief could add to his clan by adopting other families, and also had the legal right to outlaw anyone from his clan, including members of his own family. Today, anyone who has the chief's surname is automatically considered to be a member of the chief's clan. Also, anyone who offers allegiance to a chief becomes a member of the chief's clan, unless the chief decides not to accept that person's allegiance.[10]

Clan membership goes through the surname.[11] Children who take their father's surname are part of their father's clan and not their mother's. However, there have been several cases where a descendant through the maternal line has changed their surname in order to claim the chiefship of a clan, such as the late chief of the Clan MacLeod who was born John Wolridge-Gordon and changed his name to the maiden name of his maternal grandmother in order to claim the chiefship of the MacLeods.[12] Today, clans may have lists of septs. Septs are surnames, families or clans that historically, currently or for whatever reason the chief chooses, are associated with that clan. There is no official list of clan septs, and the decision of what septs a clan has is left up to the clan itself.[10] Confusingly, sept names can be shared by more than one clan, and it may be up to the individual to use his or her family history or genealogy to find the correct clan they are associated with.

Several clan societies have been granted coats of arms. In such cases, these arms are differenced from the chief's, much like a clan armiger. Former Lord Lyon Thomas Innes of Learney stated that such societies, according to the Law of Arms, are considered an "indeterminate cadet".[13]

Authority of the clans (the dùthchas and the oighreachd)

Scottish clanship contained two complementary but distinct concepts of heritage. These were firstly the collective heritage of the clan, known as their dùthchas, which was their prescriptive right to settle in the territories in which the chiefs and leading gentry of the clan customarily provided protection.[14] This concept was where all clansmen recognised the personal authority of the chiefs and leading gentry as trustees for their clan.[14] The second concept was the wider acceptance of the granting of charters by the Crown and other powerful land owners to the chiefs, chieftains and lairds which defined the estate settled by their clan.[14] This was known as their oighreachd and gave a different emphasis to the clan chief's authority in that it gave the authority to the chiefs and leading gentry as landed proprietors, who owned the land in their own right, rather than just as trustees for the clan.[14] From the beginning of Scottish clanship, the clan warrior elite, who were known as the ‘fine’, strove to be landowners as well as territorial war lords.[14]

Clans, the law and the legal process

The concept of dùthchas mentioned above held precedence in the Middle Ages; however, by the early modern period the concept of oighreachd was favoured.[14] This shift reflected the importance of Scots law in shaping the structure of clanship in that the fine were awarded charters and the continuity of heritable succession was secured.[14] The heir to the chief was known as the tainistear and was usually the direct male heir.[14] However, in some cases the direct heir was set aside for a more politically accomplished or belligerent relative. There were not many disputes over succession after the 16th century and, by the 17th century, the setting aside of the male heir was a rarity.[14] This was governed and restricted by the law of Entail, which prevented estates from being divided up amongst female heirs and therefore also prevented the loss of clan territories.[14]

The main legal process used within the clans to settle criminal and civil disputes was known as arbitration, in which the aggrieved and allegedly offending sides put their cases to a panel that was drawn from the leading gentry and was overseen by the clan chief.[14] There was no appeal against the decision made by the panel, which was usually recorded in the local royal or burgh court.[14]

Social ties

Fosterage and manrent were the most important forms of social bonding in the clans.[15] In the case of fosterage, the chief's children would be brought up by a favored member of the leading clan gentry and in turn their children would be favored by members of the clan.[15]

In the case of manrent, this was a bond contracted by the heads of families looking to the chief for territorial protection, though not living on the estates of the clan elite.[15] These bonds were reinforced by calps, death duties paid to the chief as a mark of personal allegiance by the family when their head died, usually in the form of their best cow or horse. Although calps were banned by Parliament in 1617, manrent continued covertly to pay for protection.[15]

The marriage alliance reinforced links with neighboring clans as well as with families within the territory of the clan.[15] The marriage alliance was also a commercial contract involving the exchange of livestock, money, and land through payments in which the bride was known as the tocher and the groom was known as the dowry.[15]

Clan management

Rents from those living within the clan estate were collected by the tacksmen.[16] These lesser gentry acted as estate managers, allocating the runrig strips of land, lending seed-corn and tools and arranging the droving of cattle to the Lowlands for sale, taking a minor share of the payments made to the clan nobility, the fine.[17] They had the important military role of mobilizing the Clan Host, both when required for warfare and more commonly as a large turnout of followers for weddings and funerals, and traditionally, in August, for hunts which included sports for the followers, the predecessors of the modern Highland games.[16]

Clan disputes and disorder

Where the oighreachd (land owned by the clan elite or fine) did not match the common heritage of the dùthchas (the collective territory of the clan) this led to territorial disputes and warfare.[18] The fine resented their clansmen paying rent to other landlords. Some clans used disputes to expand their territories.[19] Most notably, the Clan Campbell and the Clan Mackenzie were prepared to play off territorial disputes within and among clans to expand their own land and influence.[18] Feuding on the western seaboard was conducted with such intensity that the Clan MacLeod and the Clan MacDonald on the Isle of Skye were reputedly reduced to eating dogs and cats in the 1590s.[18]

Feuding was further compounded by the involvement of Scottish clans in the wars between the Irish Gaels and the English Tudor monarchy in the 16th century.[18] Within these clans, there evolved a military caste of members of the lesser gentry who were purely warriors and not managers, and who migrated seasonally to Ireland to fight as mercenaries.[20]

There was heavy feuding between the clans during the civil wars of the 1640s; however, by this time, the chiefs and leading gentry preferred increasingly to settle local disputes by recourse to the law.[21] After the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660, the incidents of feuding between clans declined considerably.[21] The last "clan" feud that led to a battle and which was not part of a civil war was the Battle of Mulroy, which took place on 4 August 1688.[21]

Cattle raiding, known as "reiving", had been normal practice prior to the 17th century.[21] It was also known as creach, where young men took livestock from neighbouring clans.[21] By the 17th century, this had declined and most reiving was known as sprèidh, where smaller numbers of men raided the adjoining Lowlands and the livestock taken usually being recoverable on payment of tascal (information money) and guarantee of no prosecution.[21] Some clans, such as the Clan MacFarlane and the Clan Farquharson, offered the Lowlanders protection against such raids, on terms not dissimilar to blackmail.[21]

Lowland clans

An act of the Scottish Parliament of 1597 talks of the "Chiftanis and chieffis of all clannis ... duelland in the hielands or bordouris". It has been argued that this vague phrase describes Borders families as clans.[8] The act goes on to list the various Lowland families, including the Maxwells, Johnstones, Carruthers, Turnbulls, and other famous Border Reivers' names. Further, Sir George MacKenzie of Rosehaugh, the Lord Advocate (Attorney General) writing in 1680, said: "By the term 'chief' we call the representative of the family from the word chef or head and in the Irish [Gaelic] with us the chief of the family is called the head of the clan".[8] In summarizing this material, Sir Crispin Agnew of Lochnaw Bt wrote: "So it can be seen that all along the words chief or head and clan or family are interchangeable. It is therefore quite correct to talk of the MacDonald family or the Stirling clan."[8] The idea that Highlanders should be listed as clans while the Lowlanders should be termed as families was merely a 19th-century convention.[8] Although Gaelic has been supplanted by English in the Scottish Lowlands for nearly six hundred years, it is acceptable to refer to Lowland families, such as the Douglases as "clans".[22]

The Lowland Clan MacDuff are described specifically as a "clan" in legislation of the Scottish Parliament in 1384.[23]

History

Origins

Many clans have often claimed mythological founders that reinforced their status and gave a romantic and glorified notion of their origins.[24] Most powerful clans gave themselves origins based on Irish mythology.[24] For example, there have been claims that the Clan Donald were descended from either Conn, a second-century king of Ulster, or Cuchulainn, the legendary hero of Ulster.[24] Whilst their political enemies the Clan Campbell have claimed as their progenitor Diarmaid the Boar, who was rooted in the Fingalian or Fenian Cycle.[24]

In contrast, the Clans Grant, Mackinnon and Gregor claimed ancestry from the Siol Alpin family, who descend from Alpin, father of Kenneth MacAlpin, who united the Scottish kingdom in 843.[24] Only one confederation of clans, which included the Clan Sweeney, Clan Lamont, Clan MacLea, Clan MacLachlan and Clan MacNeill, can trace their ancestry back to the fifth century Niall of the Nine Hostages, High King of Ireland.[24]

However, in reality, the progenitors of clans can rarely be authenticated further back than the 11th century, and a continuity of lineage in most cases cannot be found until the 13th or 14th centuries.[24]

The emergence of clans had more to do with political turmoil than ethnicity.[24] The Scottish Crown's conquest of Argyll and the Outer Hebrides from the Norsemen in the 13th century, which followed on from the pacification of the Mormaer of Moray and the northern rebellions of the 12th and 13th centuries, created the opportunity for war lords to impose their dominance over local families who accepted their protection. These warrior chiefs can largely be categorized as Celtic; however, their origins range from Gaelic to Norse-Gaelic and British.[24] By the 14th century, there had been further influx of kindreds whose ethnicity ranged from Norman or Anglo-Norman and Flemish, such as the Clan Cameron, Clan Fraser, Clan Menzies, Clan Chisholm and Clan Grant.[24]

During the Wars of Scottish Independence, feudal tenures were introduced by Robert the Bruce, to harness and control the prowess of clans by the award of charters for land in order to gain support in the national cause against the English.[24] For example, the Clan MacDonald were elevated above the Clan MacDougall, two clans who shared a common descent from a great Norse-Gaelic warlord named Somerled of the 12th century.[24] Clanship was thus not only a strong tie of local kinship but also of feudalism to the Scottish Crown. It is this feudal component, reinforced by Scots law, that separates Scottish clanship from the tribalism that was found in Ancient Europe or the one that is still found in the Middle East and among aboriginal groups in Australasia, Africa, and the Americas.[24]

Civil wars and Jacobitism

During the 1638 to 1651 Wars of the Three Kingdoms, all sides were 'Royalist', in the sense of a shared belief monarchy was divinely inspired. The choice of whether to support Charles I, or the Covenanter government, was largely driven by disputes within the Scottish elite. In 1639, Covenanter politician Argyll, head of Clan Campbell, was given a commission of 'fire and sword', which he used to seize MacDonald territories in Lochaber, and those held by Clan Ogilvy in Angus.[25] As a result, both clans supported Montrose's Royalist campaign of 1644–1645, in hopes of regaining them.[26]

When Charles II regained the throne in 1660, the Rescissory Act 1661 restored bishops to the Church of Scotland. This was supported by many chiefs since it suited the hierarchical clan structure and encouraged obedience to authority. Both Charles and his brother James VII used Highland levies, known as the "Highland Host", to control Campbell-dominated areas in the South-West and suppress the 1685 Argyll's Rising. By 1680, it is estimated there were fewer than 16,000 Catholics in Scotland, confined to parts of the aristocracy and Gaelic-speaking clans in the Highlands and Islands.[27]

When James was deposed in the November 1688 Glorious Revolution, choice of sides was largely opportunistic. The Presbyterian Macleans backed the Jacobites to regain territories in Mull lost to the Campbells in the 1670s; the Catholic Keppoch MacDonalds tried to sack the pro-Jacobite town of Inverness, and were bought off only after Dundee intervened.[28]

Highland involvement in the Jacobite risings was the result of their remoteness, and the feudal clan system which required tenants to provide military service. Historian Frank McLynn identifies seven primary drivers in Jacobitism, support for the Stuarts being the least important; a large percentage of Jacobite support in 1745 Rising came from Lowlanders who opposed the 1707 Union, and members of the Scottish Episcopal Church.[29]

In 1745, the majority of clan leaders advised Prince Charles to return to France, including MacDonald of Sleat and Norman MacLeod.[30] By arriving without French military support, they felt Charles failed to keep his commitments, while it is also suggested Sleat and MacLeod were vulnerable to government sanctions due to their involvement in illegally selling tenants into indentured servitude.[31]

Enough were persuaded, but the choice was rarely simple; Donald Cameron of Lochiel committed himself only after he was provided "security for the full value of his estate should the rising prove abortive," while MacLeod and Sleat helped Charles escape after Culloden.[32]

Collapse of the clan system

In 1493, James IV confiscated the Lordship of the Isles from the MacDonalds. This destabilised the region, while links between the Scottish MacDonalds and Irish MacDonnells meant unrest in one country often spilled into the other.[33] James VI took various measures to deal with the resulting instability, including the 1587 'Slaughter under trust' law, later used in the 1692 Glencoe Massacre. To prevent endemic feuding, it required disputes to be settled by the Crown, specifically murder committed in 'cold-blood', once articles of surrender had been agreed, or hospitality accepted.[34] Its first recorded use was in 1588, when Lachlan Maclean was prosecuted for the murder of his new stepfather, John MacDonald, and 17 other members of the MacDonald wedding party.[35]

Other measures had limited impact; imposing financial sureties on landowners for the good behaviour of their tenants often failed, as many were not regarded as the clan chief. The 1603 Union of the Crowns coincided with the end of the Anglo-Irish Nine Years' War, followed by land confiscations in 1608. Previously the most Gaelic part of Ireland, the Plantation of Ulster tried to ensure stability in Western Scotland by importing Scots and English Protestants. This process was often supported by the original owners; in 1607 Sir Randall MacDonnell settled 300 Presbyterian Scots families on his land in Antrim.[36] This ended the Irish practice of using Highland gallowglass, or mercenaries.

The 1609 Statutes of Iona imposed a range of measures on clan chiefs, designed to integrate them into the Scottish landed classes. Whilst there is debate over their practical effect, they were an influential force on clan elites in the long term.[37]: 39 The Statutes obliged clan chiefs to reside in Edinburgh for a large part of the year, and have their heirs educated in the English-speaking Lowlands. Lengthy periods in Edinburgh were costly. Since the Highlands were a largely non-cash economy, this meant they shifted towards commercial exploitation of their lands, rather than managing them as part of a social system. The costs of living away from their clan lands contributed to the chronic indebtedness that was increasingly common for Highland landowners, eventually leading to the sale of many of the great Highland estates in the late 18th and early 19th century.[38]: 105–107 [39]: 1–17 [37]: 37–46, 65–73, 132

During the 18th century, in an effort to increase the income from their estates, clan chiefs started to restrict the ability of tacksmen to sublet. This meant more of the rent paid by those actually farming the land went to the landowner. The result, though, was the removal of this layer of clan society. In a process that accelerated from the 1770s onward, by the early 19th century the tacksman had become a rare component of society. Historian T. M. Devine describes "the displacement of this class as one of the clearest demonstrations of the death of the old Gaelic society."[39]: 34 Many tacksmen, as well as the wealthier farmers (who were tired of repeated rent increases) chose to emigrate. This could be taken as resistance to the changes in the Highland agricultural economy, as the introduction of agricultural improvement gave rise to the Highland clearances.[40]: 9 The loss of this middle tier of Highland society represented not only a flight of capital from Gaeldom, but also a loss of entrepreneurial energy.[39]: 50 The first major step in the clearances was the decision of the Dukes of Argyll to put tacks (or leases) of farms and townships up for auction. This began with Campbell property in Kintyre in the 1710s and spread after 1737 to all their holdings. This action as a commercial landlord, letting land to the highest bidder, was a clear breach of the principle of dùthchas.[37]: 44

The Jacobite rising of 1745 used to be described as the pivotal event in the demise in clanship. There is no doubt that the aftermath of the uprising saw savage punitive expeditions against clans that had supported the Jacobites, and legislative attempts to demolish clan culture. However, the emphasis of historians now is on the conversion of chiefs into landlords in a slow transition over a long period. The successive Jacobite rebellions, in the view of T.M. Devine, simply paused the process of change whilst the military aspects of clans regained temporary importance; the apparent surge in social change after the '45 was merely a process of catching up with the financial pressures that gave rise to landlordism.[37]: 46 The various pieces of legislation that followed Culloden included the Heritable Jurisdictions Act which extinguished the right of chiefs to hold courts and transferred this role to the judiciary. The traditional loyalties of clansmen were probably unaffected by this. There is also doubt about any real effect from the banning of Highland dress (which was repealed in 1782 anyway).[37]: 57–60

The Highland Clearances saw further actions by clan chiefs to raise more money from their lands. In the first phase of clearance, when agricultural improvement was introduced, many of the peasant farmers were evicted and resettled in newly created crofting communities, usually in coastal areas. The small size of the crofts were intended to force the tenants to work in other industries, such as fishing or the kelp industry. With a shortage of work, the numbers of Highlanders who became seasonal migrants to the Lowlands increased. This gave an advantage in speaking English, as the "language of work". It was found that when the Gaelic Schools Society started teaching basic literacy in Gaelic in the early decades of the 19th century, there was an increase in literacy in English. This paradox may be explained by the annual report of the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Knowledge (SSPCK) in 1829, which stated: "so ignorant are the parents that it is difficult to convince them that it can be any benefit to their children to learn Gaelic, though they are all anxious ... to have them taught English".[39]: 110–117

The second phase of the Highland clearances affected overpopulated crofting communities which were no longer able to support themselves due to famine and/or collapse of the industries on which they relied. "Assisted passages" were provided to destitute tenants by landlords who found this cheaper than continued cycles of famine relief to those in substantial rent arrears. This applied particularly to the Western Highlands and the Hebrides. Many Highland estates were no longer owned by clan chiefs,[lower-alpha 1] but landlords of both the new and old type encouraged the emigration of destitute tenants to Canada and, later, to Australia.[42]: 370–371 [37]: 354–355 The clearances were followed by a period of even greater emigration, which continued (with a brief lull for the First World War) up to the start of the Great Depression.[37]: 2

Romantic memory

Most of the anti-clan legislation was repealed by the end of the eighteenth century as the Jacobite threat subsided, with the Dress Act restricting kilt wearing being repealed in 1782. There was soon a process of the rehabilitation of highland culture. By the nineteenth century, tartan had largely been abandoned by the ordinary people of the region, although preserved in the Highland regiments in the British army, which poor highlanders joined in large numbers until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815.[43][44] The international craze for tartan, and for idealising a romanticised Highlands, was set off by the Ossian cycle published by James Macpherson (1736–96).[45][46] Macpherson claimed to have found poetry written by the ancient bard Ossian, and published translations that acquired international popularity.[47] Highland aristocrats set up Highland Societies in Edinburgh (1784) and other centres including London (1788).[48] The image of the romantic highlands was further popularised by the works of Walter Scott. His "staging" of the royal visit of King George IV to Scotland in 1822 and the King's wearing of tartan, resulted in a massive upsurge in demand for kilts and tartans that could not be met by the Scottish linen industry. The designation of individual clan tartans was largely defined in this period and they became a major symbol of Scottish identity.[49] This "Highlandism", by which all of Scotland was identified with the culture of the Highlands, was cemented by Queen Victoria's interest in the country, her adoption of Balmoral Castle as a major royal retreat from and her interest in "tartenry".[44]

Clan symbols

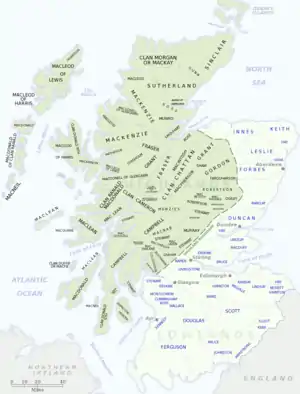

The revival of interest, and demand for clan ancestry, has led to the production of lists and maps covering the whole of Scotland giving clan names and showing territories, sometimes with the appropriate tartans. While some lists and clan maps confine their area to the Highlands, others also show Lowland clans or families. Territorial areas and allegiances changed over time, and there are also differing decisions on which (smaller) clans and families should be omitted (some alternative online sources are listed in the External links section below).

This list of clans contains clans registered with the Lord Lyon Court. The Lord Lyon Court defines a clan or family as a legally recognised group, but does not differentiate between families and clans as it recognises both terms as being interchangeable. Clans or families thought to have had a chief in the past but not currently recognised by the Lord Lyon are listed at armigerous clans.

Tartan

.png.webp)

Tartans were traditionally associated with the Highland Clans and following the end of the Dress Act of 1746 banning tartans from being worn by men and boys, "district then clan tartans" have been an important part of Scottish clans. Almost all Scottish clans have more than one tartan attributed to their surname. Although there are no rules on who can or cannot wear a particular tartan, and it is possible for anyone to create a tartan and name it almost any name they wish, the only person with the authority to make a clan's tartan "official" is the chief.[50] In some cases, following such recognition from the clan chief, the clan tartan is recorded and registered by the Lord Lyon. Once approved by the Lord Lyon, after recommendation by the Advisory Committee on Tartan, the clan tartan is then recorded in the Lyon Court Books.[51] In at least one instance a clan tartan appears in the heraldry of a clan chief and the Lord Lyon considers it to be the "proper" tartan of the clan.[lower-alpha 2]

Originally, there appears to have been no association of tartans with specific clans; instead, highland tartans were produced to various designs by local weavers and any identification was purely regional, but the idea of a clan-specific tartan gained currency in the late 18th century and in 1815 the Highland Society of London began the naming of clan-specific tartans. Many clan tartans derive from a 19th-century hoax known as the Vestiarium Scoticum. The Vestiarium was composed by the "Sobieski Stuarts", who passed it off as a reproduction of an ancient manuscript of clan tartans. It has since been proven a forgery, but despite this, the designs are still highly regarded and they continue to serve their purpose to identify the clan in question.

Crest badge

A sign of allegiance to the clan chief is the wearing of a crest badge. The crest badge suitable for a clansman or clanswoman consists of the chief's heraldic crest encircled with a strap and buckle and which contains the chief's heraldic motto or slogan. Although it is common to speak of "clan crests", there is no such thing.[53] In Scotland (and indeed all of UK) only individuals, not clans, possess a heraldic coat of arms.[54] Even though any clansmen and clanswomen may purchase crest badges and wear them to show their allegiance to his or her clan, the heraldic crest and motto always belong to the chief alone.[11] In principle, these badges should only be used with the permission of the clan chief; and the Lyon Court has intervened in cases where permission has been withheld.[55] Scottish crest badges, much like clan-specific tartans, do not have a long history, and owe much to Victorian era romanticism, having only been worn on the bonnet since the 19th century.[56] The concept of a clan badge or form of identification may have some validity, as it is commonly stated that the original markers were merely specific plants worn in bonnets or hung from a pole or spear.[57]

Clan badge

Clan badges are another means of showing one's allegiance to a Scottish clan. These badges, sometimes called plant badges, consist of a sprig of a particular plant. They are usually worn in a bonnet behind the Scottish crest badge; they can also be attached at the shoulder of a lady's tartan sash, or be tied to a pole and used as a standard. Clans which are connected historically, or that occupied lands in the same general area, may share the same clan badge. According to popular lore, clan badges were used by Scottish clans as a form of identification in battle. However, the badges attributed to clans today can be completely unsuitable for even modern clan gatherings. Clan badges are commonly referred to as the original clan symbol. However, Thomas Innes of Learney claimed the heraldic flags of clan chiefs would have been the earliest means of identifying Scottish clans in battle or at large gatherings.[58]

See also

- Armigerous clan

- Chief of the name

- Clan seat

- Clan

- Feud

- Gaels

- Gàidhealtachd

- Highland Clearances

- History of Scotland

- Irish clans

- List of Scottish clans

- Lord Lyon

- Scotia

- Scoto-Normans

- Scottish clan chief

- Scottish Gaelic

- Scottish names

- Scottish Heraldry

- Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs

- Statutes of Iona

Notes

- In Devine's study of the Highland Potato Famine, he states that, in 1846, of the 86 landowners in the famine-affected region, at least 62 (i.e. 70%) were "new purchasers who had not owned Highland property before 1800".[41]: 93–94

- The crest of the chief of Clan MacLennan is A demi-piper all Proper, garbed in the proper tartan of the Clan Maclennan.[52]

References

- Lynch, Michael, ed. (2011). Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 9780199234820.

- Mollison, Hazel (27 July 2009). "The Gathering is hailed big success after 50,000 flock to Holyrood Park". The Scotsman. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- "Surnames: Clan-based surnames". Scotland's People. National Records of Scotland. 2018. Archived from the original on 14 June 2019. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Roberts, J. L. (2000). Clan, King, and Covenant: History of the Highland Clans from the Civil War to the Glencoe Massacre. Edinburgh University Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-7486-1393-5.

- Lynch, Michael, ed. (2011). Oxford Companion to Scottish History. Oxford University Press. p. 23. ISBN 9780199234820.

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): p. 28.

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): p. 29.

- Agnew of Lochnaw, Sir Crispin, Bt (13 August 2001). "Clans, Families and Septs". ElectricScotland.com. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- "What is a clan?". Lyon-Court.com. Court of the Lord Lyon. Archived from the original on 17 January 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- "Who is a member of a clan?". Lyon-Court.com. Court of the Lord Lyon. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- Court of the Lord Lyon. "Information Leaflet No. 2". Retrieved 25 April 2009 – via ElectricScotland.com.

- "John MacLeod of MacLeod". The Independent. London. 17 March 2007. Archived from the original on 13 May 2011.

- Innes of Learney (1971): pp. 55–57.

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): p. 14.

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): p. 15.

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): pp. 15–16.

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): pp. 15–16 .

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): p. 16.

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): p. 16 .

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): pp. 16–17.

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): p. 17.

- Scots Kith & Kin. HarperCollins. 2014. p. 53. ISBN 9780007551798.

- Grant, Alexander; Stringer, Keith J. (1998). Medieval Scotland: Crown, Lordship and Community. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-7486-1110-2..

- Way of Plean; Squire (1994): pp. 13–14.

- Royle 2004, pp. 109–110.

- Lenihan 2001, p. 65.

- Mackie, Lenman, Parker (1986): pp. 237–238.

- Lenman 1995, p. 44.

- McLynn 1982, pp. 97–133.

- Riding 2016, pp. 83–84.

- Pittock 2004.

- Riding 2016, pp. 465–467.

- Lang 1912, pp. 284–286.

- Harris 2015, pp. 53–54.

- Levine 1999, p. 129.

- Elliott 2000, p. 88.

- Devine, T. M. (2018). The Scottish Clearances: A History of the Dispossessed, 1600–1900. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0241304105.

- Dodgshon, Robert A. (1998). From Chiefs to Landlords: Social and Economic Change in the Western Highlands and Islands, c.1493–1820. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1034-0.

- Devine, T. M. (2013). Clanship to Crofters' War: The Social Transformation of the Scottish Highlands. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-9076-9.

- Richards, Eric (2013). The Highland Clearances: People, Landlords and Rural Turmoil. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 978-1-78027-165-1.

- Devine, T. M. (1995). The Great Highland Famine: Hunger, Emigration and the Scottish Highlands in the Nineteenth Century. Edinburgh: Birlinn. ISBN 1-904607-42-X.

- Lynch, Michael (1992). Scotland: A New History. London: Pimlico. ISBN 9780712698931.

- Roberts (2002) pp. 193–5.

- Sievers (2007), pp. 22–5.

- Morère (2004), pp. 75–6.

- Ferguson (1998), p. 227.

- Buchan (2003), p. 163.

- Calloway (2008), p. 242.

- Milne (2010), p. 138.

- "Tartans". Lyon-Court.com. Court of the Lord Lyon. Archived from the original on 14 January 2008. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- Campbell of Airds (2000): pp. 259–261.

- Way of Plean; Squire (2000): p. 214.

- "Crests". Lyon-Court.com. Court of the Lord Lyon. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- "The History of Arms". Lyon-Court.com. Court of the Lord Lyon. Retrieved 26 February 2008.

- Adam; Innes of Learney (1970)

- Campbell of Airds (2002): pp. 289–290.

- Moncreiffe of that Ilk (1967): p. 20.

- Adam; Innes of Learney (1970): pp. 541–543

Sources

- Adam, Frank; Innes of Learney, Thomas (1970). The Clans, Septs & Regiments of the Scottish Highlands (8th ed.). Edinburgh: Johnston and Bacon.

- Brown, Ian (2020). Performing Scottishness: Enactment and National Identities. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3030394066.

- Buchan, James (2003). Crowded with Genius. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-06-055888-8.

- Calloway, C. G. (2008). White People, Indians, and Highlanders: Tribal People and Colonial Encounters in Scotland and America: Tribal People and Colonial Encounters in Scotland and America. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971289-2.

- Campbell, Alastair (2000). A History of Clan Campbell, Volume 1: From Origins to the Battle of Flodden. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-902930-17-6.

- Campbell, Alastair (2002). A History of Clan Campbell, Volume 2: From Flodden to the Restoration. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-902930-18-3.

- Beresford Ellis, Peter (1990). MacBeth, High King of Scotland 1040–1057. Dundonald, Belfast: Blackstaff Press. ISBN 978-0-85640-448-1.

- Elliott, Marianne (2000). The Catholics of Ulster. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0713994643.

- Ferguson, William (1998). The Identity of the Scottish Nation: an Historic Quest. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-1071-6.

- Harris, Tim (2015). Rebellion: Britain's First Stuart Kings, 1567–1642. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0198743118.

- Innes of Learney, Thomas (1971). The Tartans of the Clans and Families of Scotland (8th ed.). Edinburgh: Johnston and Bacon.

- Lang, Andrew (1912). The History Of Scotland: Volume 3: From the early 17th century to the death of Dundee (2016 ed.). Jazzybee Verlag. ISBN 978-3849685645.

- Lenihan, Padraig (2001). Conquest and Resistance: War in Seventeenth-Century Ireland (History of Warfare). Brill. ISBN 978-9004117433.

- Lenman, Bruce (1995). The Jacobite Risings in Britain, 1689–1746. Scottish Cultural Press. ISBN 189821820X.

- Levine, Mark, ed. (1999). The Massacre in History (War and Genocide). Bergahn Books. ISBN 1571819355.

- Mackie, J. D.; Lenman, Bruce (1986). Parker, Geoffrey (ed.). A History of Scotland. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0880290401.

- McLynn, Frank (1982). "Issues and Motives in the Jacobite Rising of 1745". The Eighteenth Century. 23 (2): 177–181. JSTOR 41467263.

- Milne, N. C. (2010). Scottish Culture and Traditions. Paragon Publishing. ISBN 978-1-899820-79-5.

- Dawson, Deidre; Morère, Pierre (2004). Scotland and France in the Enlightenment. Bucknell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8387-5526-6.

- Moncreiffe of that Ilk, Iain (1967). The Highland Clans. London: Barrie & Rocklif.

- Pittock, Murray (2004). "Charles Edward Stuart; styled Charles; known as the Young Pretender, Bonnie Prince Charlie". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5145. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Riding, Jacqueline (2016). Jacobites: A New History of the 45 Rebellion. Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1408819128.

- Roberts, J. L. (2002). The Jacobite Wars: Scotland and the Military Campaigns of 1715 and 1745. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-1-902930-29-9.

- Royle, Trevor (2004). Civil War: The War of the Three Kingdoms 1638-1660. Brown, Little. ISBN 978-0316861250.

- Sievers, Marco (2007). The Highland Myth as an Invented Tradition of 18th and 19th Century and Its Significance for the Image of Scotland. Edinburgh: GRIN Verlag. ISBN 978-3-638-81651-9.

- Way of Plean, George; Squire, Romilly (1995). Clans and Tartans: Collins Pocket Reference. Glasgow: Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-470810-5.

- Way of Plean, George; Squire, Romilly (2000). Clans & Tartans. Glasgow: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-472501-8.

- Way of Plean, George; Squire, Romilly (1994). Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. Glasgow: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-00-470547-5.

Further reading

- Devine, T. M. (2013). Clanship to Crofters' War: The Social Transformation of the Scottish Highlands. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-9076-9.

- Dodgshon, Robert A. (1998). From Chiefs to Landlords: Social and Economic Change in the Western Highlands and Islands, c. 1493–1820. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 0-7486-1034-0.

- Macinnes, Allan I. (1996). Clanship, Commerce and the House of Stewart, 1603–1788. East Linton: Tuckwell Press. ISBN 1-898410-43-7.

External links

- The Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs

- The Court of the Lord Lyon – the official heraldic authority of Scotland

- The Scottish Register of Tartans – official Scottish government database of tartan registrations, established in 2009

- The Scottish Tartans Authority – Scottish registered charity and the only extant private organisation dedicated to the preservation and promotion of tartans

- Council of Scottish Clans and Associations (COSCA, US-based)

- The Scottish Australian Heritage Council

- "Scottish Clans and Families"" – clans registered with the Court of the Lord Lyon (unofficial list via the Electric Scotland website)

- "All Hail the Chiefs: The Unlikely Leaders of Scotland's Modern Clans". The Independent. 19 July 2009.

- SkyeLander: Scottish History Online blog by Robert M. Gunn