Priming (psychology)

Priming is a phenomenon whereby exposure to one stimulus influences a response to a subsequent stimulus, without conscious guidance or intention.[1][2] The priming effect refers to the positive or negative effect of a rapidly presented stimulus (priming stimulus) on the processing of a second stimulus (target stimulus) that appears shortly after. Generally speaking, the generation of priming effect depends on the existence of some positive or negative relationship between priming and target stimuli. For example, the word nurse is recognized more quickly following the word doctor than following the word bread. Priming can be perceptual, associative, repetitive, positive, negative, affective, semantic, or conceptual. Priming effects involve word recognition, semantic processing, attention, unconscious processing, and many other issues, and are related to differences in various writing systems. Research, however, has yet to firmly establish the duration of priming effects,[3][4] yet their onset can be almost instantaneous.[5]

Priming works most effectively when the two stimuli are in the same modality. For example, visual priming works best with visual cues and verbal priming works best with verbal cues. But priming also occurs between modalities,[6] or between semantically related words such as "doctor" and "nurse".[7][8]

The study of priming and interpretation of its research has been subject to controversy due to a replication crisis,[9] publication bias,[10] and the experimenter effect.[11]

Types

Positive and negative priming

The terms positive and negative priming refer to when priming affects the speed of processing. A positive prime speeds up processing, while a negative prime lowers the speed to slower than un-primed levels.[12] Positive priming is caused by simply experiencing the stimulus,[13] while negative priming is caused by experiencing the stimulus, and then ignoring it.[12][14] Positive priming effects happen even if the prime is not consciously perceived.[13] The effects of positive and negative priming are visible in event-related potential (ERP) readings.[15]

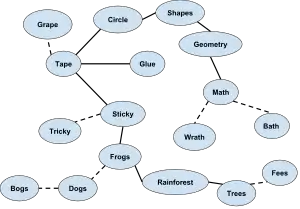

Positive priming is thought to be caused by spreading activation.[13] This means that the first stimulus activates parts of a particular representation or association in memory just before carrying out an action or task. The representation is already partially activated when the second stimulus is encountered, so less additional activation is needed for one to become consciously aware of it.

Negative priming is more difficult to explain. Many models have been hypothesized, but currently the most widely accepted are the distractor inhibition and episodic retrieval models.[12] In the distractor inhibition model, the activation of ignored stimuli is inhibited by the brain.[12] The episodic retrieval model hypothesizes that ignored items are flagged 'do-not-respond' by the brain. Later, when the brain acts to retrieve this information, the tag causes a conflict. The time taken to resolve this conflict causes negative priming.[12] Although both models are still valid, recent scientific research has led scientists to lean away from the distractor inhibitor model.[12]

Perceptual and conceptual priming

The difference between perceptual and conceptual types of priming is whether items with a similar form or items with a similar meaning are primed, respectively.

Perceptual priming is based on the form of the stimulus and is enhanced by the match between the early and later stimuli. Perceptual priming is sensitive to the modality and exact format of the stimulus. An example of perceptual priming is the identification of an incomplete word in a word-stem completion test. The presentation of the visual prime does not have to be perfectly consistent with later testing presentations in order to work. Studies have shown that, for example, the absolute size of the stimuli can vary and still provide significant evidence of priming.[16]

Conceptual priming is based on the meaning of a stimulus and is enhanced by semantic tasks. For example, the word table will show conceptual priming effects on the word chair, because the words belong to the same category.[17]

Repetition

Repetition priming, also called direct priming, is a form of positive priming. When a stimulus is experienced, it is also primed. This means that later experiences of the stimulus will be processed more quickly by the brain.[18] This effect has been found on words in the lexical decision task.

Semantic

In semantic priming, the prime and the target are from the same semantic category and share features.[19] For example, the word dog is a semantic prime for wolf, because the two are similar animals. Semantic priming is theorized to work because of spreading activation within associative networks.[13] When a person thinks of one item in a category, similar items are stimulated by the brain. Even if they are not words, morphemes can prime for complete words that include them.[20] An example of this would be that the morpheme 'psych' can prime for the word 'psychology'.

In support with further detail, when an individual processes a word sometimes that word can be affected when the prior word is linked semantically. Previous studies have been conducted, focusing on priming effects having a rapid rise time and a hasty decay time. For example, an experiment by Donald Frost researched the decay time of semantic facilitation in lists and sentences. Three experiments were conducted and it was found that semantic relationships within words differs when words occur in sentences rather than lists. Thus, supporting the ongoing discourse model.[21]

Associative priming

In associative priming, the target is a word that has a high probability of appearing with the prime, and is "associated" with it but not necessarily related in semantic features. The word dog is an associative prime for cat, since the words are closely associated and frequently appear together (in phrases like "raining cats and dogs").[22] A similar effect is known as context priming. Context priming works by using a context to speed up processing for stimuli that are likely to occur in that context. A useful application of this effect is reading written text.[23] The grammar and vocabulary of the sentence provide contextual clues for words that will occur later in the sentence. These later words are processed more quickly than if they had been read alone, and the effect is greater for more difficult or uncommon words.[23]

Response priming

In the psychology of visual perception and motor control, the term response priming denotes a special form of visuomotor priming effect. The distinctive feature of response priming is that prime and target are presented in quick succession (typically, less than 100 milliseconds apart) and are coupled to identical or alternative motor responses.[24][25] When a speeded motor response is performed to classify the target stimulus, a prime immediately preceding the target can thus induce response conflicts when assigned to a different response as the target. These response conflicts have observable effects on motor behavior, leading to priming effects, e.g., in response times and error rates. A special property of response priming is its independence from visual awareness of the prime: For example, response priming effects can increase under conditions where visual awareness of the prime is decreasing.[26][27]

Masked priming

The masked priming paradigm has been widely used in the last two decades in order to investigate both orthographic and phonological activations during visual word recognition. The term "masked" refers to the fact that the prime word or pseudoword is masked by symbols such as ###### that can be presented in a forward manner (before the prime) or a backward manner (after the prime). These masks enable to diminish the visibility of the prime. The prime is usually presented less than 80 ms (but typically between 40-60 ms) in this paradigm. In all, the short SOA (Stimuli Onset Asynchrony, i.e. the time delay between the onset of the mask and the prime) associated with the masking make the masked priming paradigm a good tool to investigate automatic and irrespective activations during visual word recognition.[28] Forster has argued that masked priming is a purer form of priming, as any conscious appreciation of the relationship between the prime and the target is effectively eliminated, and thus removes the subject's ability to use the prime strategically to make decisions. Results from numerous experiments show that certain forms of priming occur that are very difficult to occur with visible primes. One such example is form-priming, where the prime is similar to, but not identical to the target (e.g., the words nature and mature).[29][30] Form priming is known to be affected by several psycholinguistic properties such as prime-target frequency and overlap. If a prime is higher frequency than the target, lexical competition occurs, whereas if the target has a higher frequency than the prime, then the prime pre-activates the target[31] and if the prime and target differ by one letter and one phoneme, the prime competes with the target, leading to lexical competition.[32] Not only is it affected by the prime and target, but also by individual differences such that people with well-established lexical representations are more likely to show lexical competition than people with less-established lexical representation.[33][34][35][36][37][38]

Kindness priming

Kindness priming is a specific form of priming that occurs when a subject experiences an act of kindness and subsequently experiences a lower threshold of activation when subsequently encountering positive stimuli. A unique feature of kindness priming is that it causes a temporarily increased resistance to negative stimuli in addition to the increased activation of positive associative networks.[39] This form of priming is closely related to affect priming.

Affective priming

Affective or affect priming entails the evaluation of people, ideas, objects, goods, etc., not only based on the physical features of those things, but also on affective context. Most research and concepts about affective priming derive from the affective priming paradigm where people are asked to evaluate or respond to a stimuli following positive, neutral, or negative primes. Some research suggests that valence (positive vs. negative) has a stronger effect than arousal (low vs. high) on lexical-decision tasks.[40] Affective priming might also be more diffuse and stronger when the prime barely enters conscious awareness.[41] Evaluation of emotions can be primed by other emotions as well. Thus, neutral pictures, when presented after unpleasant pictures, are perceived as more pleasant than when presented after pleasant pictures.[42]

Cultural priming

Cultural priming is a technique employed in the field of cross-cultural psychology and social psychology to understand how people interpret events and other concepts, like cultural frame switching and self-concept.[43]: 270 [44] For example, Hung and his associate display participants a different set of culture related images, like U.S. Capitol building vs Chinese temple, and then watch a clip of fish swimming ahead of a group of fishes.[45] When exposed to the latter one, Hong Kong participants are more likely to reason in a collectivistic way.[46]: 187 In contrast, their counterparts who view western images are more likely to give a reverse response and focus more on that individual fish.[47]: 787 [48] People from bi-culture society when primed with different cultural icons, they are inclined to make cultural activated attribution.[43]: 327 One method is the Pronoun circling task, a type of cultural priming task, which involves asking participants to consciously circle pronouns like "We", "us", "I", and "me" during paragraph reading.[49][50]: 381

Anti-priming

Anti-priming is a measurable impairment in processing information owing to recent processing of other information when the representations of information overlap and compete. Strengthening one representation after its usage causes priming for that item but also anti-priming for some other, non-repeated items.[51] For example, in one study, identification accuracy of old Chinese characters was significantly higher than baseline measurements (i.e., the priming effect), while identification accuracy of novel characters was significantly lower than baseline measurements (i.e., the anti-priming effect).[52] Anti-priming is said to be the natural antithesis of repetition priming, and it manifests when two objects share component features, thereby having overlapping representations.[53] However, one study failed to find anti-priming effects in a picture-naming task even though repetition priming effects were observed. Researchers argue that anti-priming effects may not be observed in a small time-frame.[53]

Measuring the effects of priming

Priming effects can be found with many of the tests of implicit memory. Tests such as the word-stem completion task, and the word fragment completion task measure perceptual priming. In the word-stem completion task, participants are given a list of study words, and then asked to complete word "stems" consisting of 3 letters with the first word that comes to mind. A priming effect is observed when participants complete stems with words on the study list more often than with novel words. The word fragment completion task is similar, but instead of being given the stem of a word, participants are given a word with some letters missing. The lexical decision task can be used to demonstrate conceptual priming.[7][54] In this task, participants are asked to determine if a given string is a word or a nonword. Priming is demonstrated when participants are quicker to respond to words that have been primed with semantically-related words, e.g., faster to confirm "nurse" as a word when it is preceded by "doctor" than when it is preceded by "butter". Other evidence has been found through brain imaging and studies from brain injured patients. Another example of priming in healthcare research was studying if safety behaviors of nurses could be primed by structuring change of shift report.[55] A pilot simulation study found that there is early evidence to show that safety behaviors can be primed by including safety language into report.[55]

Effects of brain injuries

Amnesia

Patients with amnesia are described as those who have suffered damage to their medial temporal lobe, resulting in the impairment of explicit recollection of everyday facts and events. Priming studies on amnesic patients have varying results, depending on both the type of priming test done, as well as the phrasing of the instructions.

Amnesic patients do as well on perceptual priming tasks as healthy patients,[56] however they show some difficulties completing conceptual priming tasks, depending on the specific test. For example, they perform normally on category instance production tasks, but show impaired priming on any task that involves answering general knowledge questions.[57][58]

Phrasing of the instructions associated with the test has had a dramatic impact on an amnesic's ability to complete the task successfully. When performing a word-stem completion test, patients were able to successfully complete the task when asked to complete the stem using the first word that came to mind, but when explicitly asked to recall a word to complete the stem that was on the study list, patients performed at below-average levels.[59]

Overall, studies from amnesic patients indicate that priming is controlled by a brain system separate from the medial temporal system that supports explicit memory.

Aphasia

Perhaps the first use of semantic priming in neurological patients was with stroke patients with aphasia. In one study, patients with Wernicke's aphasia who were unable to make semantic judgments showed evidence of semantic priming, while patients with Broca's aphasia who were able to make semantic judgments showed less consistent priming than those with Wernicke's aphasia or normal controls. This dissociation was extended to other linguistic categories such phonology and syntactic processing by Blumstein, Milberg and their colleagues.[60]

Dementia

Patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD), the most common form of dementia, have been studied extensively as far as priming goes. Results are conflicting in some cases, but overall, patients with AD show decreased priming effects on word-stem completion and free association tasks, while retaining normal performance on lexical decision tasks.[61] These results suggest that AD patients are impaired in any sort of priming task that requires semantic processing of the stimuli, while priming tasks that require visuoperceptual interpretation of stimuli are unaffected by Alzheimers.

Focal cortical lesions

Patient J.P., who suffered a stroke in the left medial/temporal gyrus, resulting in auditory verbal agnosia - the inability to comprehend spoken words, but maintaining the ability to read and write, and with no effects to hearing ability. J.P. showed normal perceptual priming, but his conceptual priming ability for spoken words was, expectedly, impaired.[62] Another patient, N.G., who suffered from prosopanomia (the inability to retrieve proper names) following damage to his left temporal lobe, was unable to spontaneously provide names of persons or cities, but was able to successfully complete a word-fragment completion exercise following priming with these names. This demonstrated intact perceptual priming abilities.[63]

Cognitive neuroscience

Perceptual priming

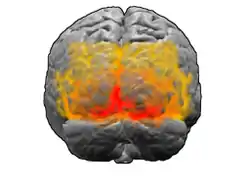

Priming while improving performance decreases neural processing in the cerebral cortex of sensory stimuli with stimulus repetition. This has been found in single-cell recordings[64] and in electroencephalography (EEG) upon gamma waves,[65] with PET[66] and functional MRI.[67] This reduction is due to representational sharpening in the early sensory areas which reduces the number of neurons representing the stimulus. This leads to a more selective activation of neurons representing objects in higher cognitive areas.[68]

Conceptual priming

Conceptual priming has been linked to reduced blood flow in the left prefrontal cortex.[69] The left prefrontal cortex is believed to be involved in the semantic processing of words, among other tasks.[70]

The view that perceptual priming is controlled by the extrastriate cortex while conceptual priming is controlled by the left prefrontal cortex is undoubtedly an oversimplified view of the process, and current work is focused on elucidating the brain regions involved in priming in more detail.[71]

In daily life

Priming is thought to play a large part in the systems of stereotyping.[72] This is because attention to a response increases the frequency of that response, even if the attended response is undesired. [72][73] The attention given to these response or behaviors primes them for later activation.[72] Another way to explain this process is automaticity. If trait descriptions, for instance "stupid" or "friendly", have been frequently or recently used, these descriptions can be automatically used to interpret someone's behavior. An individual is unaware of this, and this may lead to behavior that may not agree with their personal beliefs.[74]

This can occur even if the subject is not conscious of the priming stimulus.[72] An example of this was done by John Bargh et al. in 1996. Subjects were implicitly primed with words related to the stereotype of elderly people (example: Florida, forgetful, wrinkle). While the words did not explicitly mention speed or slowness, those who were primed with these words walked more slowly upon exiting the testing booth than those who were primed with neutral stimuli.[72] Similar effects were found with rude and polite stimuli: those primed with rude words were more likely to interrupt an investigator than those primed with neutral words, and those primed with polite words were the least likely to interrupt.[72] A 2008 study showed that something as simple as holding a hot or cold beverage before an interview could result in pleasant or negative opinion of the interviewer.[75]

These findings have been extended to therapeutic interventions. For example, a 2012 study suggested that presented with a depressed patient who "self-stereotypes herself as incompetent, a therapist can find ways to prime her with specific situations in which she had been competent in the past... Making memories of her competence more salient should reduce her self-stereotype of incompetence."[76]

Replicability controversy and criticism

The replicability and interpretation of goal-priming findings has become controversial.[9] Studies in 2012 failed to replicate findings, including age priming,[11] with additional reports of failure to replicate this and other findings such as social-distance also reported.[77][78]

Priming is often considered to play a part in the success of sensory branding of products and connected to ideas like crossmodal correspondencies and sensation transference. Known effects are e.g. consumers perceiving lemonade suddenly as sweeter when the logo of the drink is more saturated towards yellow.[79]

Although semantic, associative, and form priming are well established,[80] some longer-term priming effects were not replicated in further studies, casting doubt on their effectiveness or even existence.[81] Nobel laureate and psychologist Daniel Kahneman has called on priming researchers to check the robustness of their findings in an open letter to the community, claiming that priming has become a "poster child for doubts about the integrity of psychological research."[82] In 2022, Kahneman described behavioral priming research as "effectively dead."[83] Other critics have asserted that priming studies suffer from major publication bias,[10] experimenter effect[11] and that criticism of the field is not dealt with constructively.[84]

See also

- Intertrial priming

- Implicit association test

References

- Weingarten E, Chen Q, McAdams M, Yi J, Hepler J, Albarracín D (May 2016). "From primed concepts to action: A meta-analysis of the behavioral effects of incidentally presented words". Psychological Bulletin. 142 (5): 472–97. doi:10.1037/bul0000030. PMC 5783538. PMID 26689090.

- Bargh JA, Chartrand TL (2000). "Studying the Mind in the Middle: A Practical Guide to Priming and Automaticity Research". In Reis H, Judd C (eds.). Handbook of Research Methods in Social Psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–39.

- Tulving E, Schacter DL, Stark HA (1982). "Priming Effects in Word Fragment Completion are independent of Recognition Memory". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 8 (4): 336–342. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.8.4.336.

- Bargh JA, Gollwitzer PM, Lee-Chai A, Barndollar K, Trötschel R (December 2001). "The automated will: nonconscious activation and pursuit of behavioral goals". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 81 (6): 1014–27. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.81.6.1014. PMC 3005626. PMID 11761304.

- Ben-Haim MS, Chajut E, Hassin RR, Algom D (April 2015). "Speeded naming or naming speed? The automatic effect of object speed on performance". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 144 (2): 326–38. doi:10.1037/a0038569. PMID 25559652.

- Several researchers, for example, have used cross-modal priming to investigate syntactic deficits in individuals with damage to Broca's area of the brain. See the following:

- Zurif E, Swinney D, Prather P, Solomon J, Bushell C (October 1993). "An on-line analysis of syntactic processing in Broca's and Wernicke's aphasia". Brain and Language. 45 (3): 448–64. doi:10.1006/brln.1993.1054. PMID 8269334. S2CID 8791285.

- Swinney D, Zurif E, Prather P, Love T (March 1996). "Neurological distribution of processing resources underlying language comprehension". Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 8 (2): 174–84. doi:10.1162/jocn.1996.8.2.174. PMID 23971422. S2CID 1836757. }}

- For an overview, see also Zurif EB (1995). "Brain Regions of Relevance to Syntactic Processing". In Larson R, Segal G (eds.). Knowledge of Meaning: An Introduction to Semantic Theory. MIT Press.

- Meyer DE, Schvaneveldt RW (1971). "Facilitation in recognizing pairs of words: Evidence of a dependence between retrieval operations". Journal of Experimental Psychology. 90 (2): 227–234. doi:10.1037/h0031564. PMID 5134329. S2CID 36672941.

-

Friederici AD, Steinhauer K, Frisch S (May 1999). "Lexical integration: sequential effects of syntactic and semantic information". Memory & Cognition. 27 (3): 438–53. doi:10.3758/BF03211539. PMID 10355234.

Semantic priming refers to the finding that word recognition is typically faster when the target word (e.g., doctor) is preceded by a semantically related prime word (e.g., nurse).

- B. Bower. (2012). The hot and cold of priming: Psychologists are divided on whether unnoticed cues can influence behavior. Science News, 181, The Hot and Cold of Priming

- Bower B. "The Hot and Cold of Priming". Science News. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- Doyen S, Klein O, Pichon CL, Cleeremans A (2012). "Behavioral priming: it's all in the mind, but whose mind?". PLOS ONE. 7 (1): e29081. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...729081D. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029081. PMC 3261136. PMID 22279526.

- Mayr S, Buchner A (2007). "Negative Priming as a Memory Phenomenon". Zeitschrift für Psychologie. 215 (1): 35–51. doi:10.1027/0044-3409.215.1.35.

- Reisberg, Daniel: Cognition: Exploring the Science of the Mind (2007), page 255, 517.

- Neumann E, DeSchepper BG (November 1991). "Costs and benefits of target activation and distractor inhibition in selective attention". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 17 (6): 1136–45. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.17.6.1136. PMID 1838386.

- Bentin S, McCarthy G, Wood CC (April 1985). "Event-related potentials, lexical decision and semantic priming". Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 60 (4): 343–55. doi:10.1016/0013-4694(85)90008-2. PMID 2579801.

- Biederman I, Cooper EE (1992). "Size Invariance in Visual Object Priming". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 18 (1): 121–133. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.18.1.121.

- Vaidya CJ, Gabrieli JD, Monti LA, Tinklenberg JR, Yesavage JA (October 1999). "Dissociation between two forms of conceptual priming in Alzheimer's disease" (PDF). Neuropsychology. 13 (4): 516–24. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.13.4.516. PMID 10527059. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 19, 2011.

- Forster KI, Davis C (1984). "Repetition Priming and Frequency Attenuation". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 10 (4): 680–698. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.10.4.680.

- Ludovic Ferrand and Boris New: Semantic and associative priming in the mental lexicon, found on: boris.new.googlepages.com/Semantic-final-2003.pdf

- Marslen-Wilson W, Tyler LK, Waksler R, Older L (1994). "Morphology and Meaning in the English Mental Lexicon". Psychological Review. 101 (1): 3–33. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.294.7035. doi:10.1037/0033-295x.101.1.3.

- Foss, Donald (April 23, 1982). "A discourse on semantic priming". Cognitive Psychology. 14 (4): 590–607. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(82)90020-2. PMID 7140212. S2CID 42931448.

- Matsukawa J, Snodgrass JG, Doniger GM (November 2005). "Conceptual versus perceptual priming in incomplete picture identification". Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 34 (6): 515–40. doi:10.1007/s10936-005-9162-5. hdl:2297/1842. PMID 16341912. S2CID 18396648.

- Stanovich KE, West RF (March 1983). "On priming by a sentence context". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 112 (1): 1–36. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.112.1.1. PMID 6221061.

- Klotz W, Wolff P (1995). "The effect of a masked stimulus on the response to the masking stimulus". Psychological Research. 58 (2): 92–101. doi:10.1007/bf00571098. PMID 7480512. S2CID 25422424.

- Klotz W, Neumann O (1999). "Motor activation without conscious discrimination in metacontrast masking". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 25 (4): 976–992. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.25.4.976.

- Vorberg, D., Mattler, U., Heinecke, A., Schmidt, T., & Schwarzbach, J. Different time courses for visual perception and action priming. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, 100, 2003, p. 6275-6280.

- Schmidt, T., & Vorberg, D. Criteria for unconscious cognition: Three types of dissociation. In: Perception & Psychophysics, 68, 2006, p. 489-504.

- Forster KI, Davis C (1984). "Repetition priming and frequency attenuation in lexical decision". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 10 (4): 680–698. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.10.4.680.

- Forster KI, Davis C (1984). "The density constraint on form-priming in the naming task: Interference effects from a masked prime". Journal of Memory and Language. 30 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1016/0749-596X(91)90008-8.

- Forster KI, Davis C, Schoknecht C, Carter R (1987). "Masked priming with graphemically related forms: Repetition or partial activation?". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology A. 39A (2): 211–251. doi:10.1080/14640748708401785. S2CID 144992122.

- Segui, Juan; Grainger, Jonathan (1990). "APA PsycNet". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 16 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.16.1.65. S2CID 27807746. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- Davis, C. J.; Lupker, S. J. (2006). "APA PsycNet". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance. 32 (3): 668–687. doi:10.1037/0096-1523.32.3.668. PMID 16822131. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- Andrews, S.; Hersch, J. (2010). "APA PsycNet". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 139 (2): 299–318. doi:10.1037/a0018366. PMID 20438253. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- Andrews, S.; Lo, S. (2012). "APA PsycNet". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 38 (1): 152–163. doi:10.1037/a0024953. PMID 21875252. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- Perfetti, Charles (September 26, 2007). "Reading Ability: Lexical Quality to Comprehension". Scientific Studies of Reading. 11 (4): 357–383. doi:10.1080/10888430701530730. ISSN 1088-8438. S2CID 62203167.

- Adelman, James S.; Johnson, Rebecca L.; McCormick, Samantha F.; McKague, Meredith; Kinoshita, Sachiko; Bowers, Jeffrey S.; Perry, Jason R.; Lupker, Stephen J.; Forster, Kenneth I.; Cortese, Michael J.; Scaltritti, Michele (December 1, 2014). "A behavioral database for masked form priming". Behavior Research Methods. 46 (4): 1052–1067. doi:10.3758/s13428-013-0442-y. ISSN 1554-3528. PMID 24488815. S2CID 935533.

- Elsherif, M.M; Wheeldon, L.R.; Frisson, S. (September 1, 2021). "Phonological precision for word recognition in skilled readers". Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 75 (6): 1021–1040. doi:10.1177/17470218211046350. ISSN 1747-0218. PMC 9016675. PMID 34467802.

- Elsherif, M. M.; Frisson, S.; Wheeldon, L. R. (August 25, 2022). "Orthographic precision for word naming in skilled readers". Language, Cognition and Neuroscience. 0 (0): 1–20. doi:10.1080/23273798.2022.2108091. ISSN 2327-3798.

- Carlson, Charlin, Norman, http://psycnet.apa.org/journals/psp/55/2/211/, Positive mood and helping behavior: A test of six hypotheses, 1989

- Yao, Zhao; Zhu, Xiangru; Luo, Wenbo (October 1, 2019). "Valence makes a stronger contribution than arousal to affective priming". PeerJ. 7: e7777. doi:10.7717/peerj.7777. ISSN 2167-8359. PMC 6777477. PMID 31592186.

- Rotteveel, M.; de Groot, P.; Geutskens, A.; Phaf, R. H. (December 2001). "Stronger suboptimal than optimal affective priming?". Emotion. 1 (4): 348–364. doi:10.1037/1528-3542.1.4.348. ISSN 1528-3542. PMID 12901397.

- Kosonogov, Vladimir (December 30, 2020). "The effects of the order of picture presentation on the subjective emotional evaluation of pictures". Psicologia. 34 (2): 171–178. doi:10.17575/psicologia.v34i2.1608. ISSN 2183-2471.

- Kitayama S, Cohen D (2007). Handbook of cultural psychology. New York: Guilford Press. ISBN 9781593857325. OCLC 560675525.

- Liu Z, Cheng M, Peng K, Zhang D (September 30, 2015). "Self-construal priming selectively modulates the scope of visual attention". Frontiers in Psychology. 6: 1508. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01508. PMC 4588108. PMID 26483747.

- Hong YY, Chiu CY, Kung TM (1997). "Bringing culture out in front: Effects of cultural meaning system activation on social cognition". Progress in Asian Social Psychology. 1: 135–46. }}

- Myers DG (2010). Social psychology (Tenth ed.). New York, NY. ISBN 9780073370668. OCLC 667213323.

- Kruglanski AW, Higgins ET (2007). Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles. Guilford Press. ISBN 9781572309180.

- Hong YY, Morris MW, Chiu CY, Benet-Martínez V (July 2000). "Multicultural minds. A dynamic constructivist approach to culture and cognition". The American Psychologist. 55 (7): 709–20. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.55.7.709. PMID 10916861.

- Oyserman D, Sorensen N, Reber R, Chen SX (August 2009). "Connecting and separating mind-sets: culture as situated cognition". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 97 (2): 217–35. doi:10.1037/a0015850. PMID 19634972.

- Keith KD (April 12, 2018). Culture across the curriculum : a psychology teacher's handbook. New York. ISBN 9781107189973. OCLC 1005687090.

- Marsolek, Chad J. (May 2008). "What antipriming reveals about priming". Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 12 (5): 176–181. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2008.02.005. ISSN 1364-6613. PMID 18403251. S2CID 44554182.

- Zhang, Feng; Fairchild, Amanda J.; Li, Xiaoming (2017). "Visual Antipriming Effect: Evidence from Chinese Character Identification". Frontiers in Psychology. 8: 1791. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01791. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 5651016. PMID 29089908.

- Humphries, Ailsa; Chen, Zhe; Wiltshire, Jonathan (March 2020). "Repetition priming with no antipriming in picture identification". Vision Research. 168: 9–17. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2019.09.011. ISSN 1878-5646. PMID 32044587. S2CID 211054740.

- Schvaneveldt RW, Meyer DE (1973). "Retrieval and comparison processes in semantic memory". In Kornblum S (ed.). Attention and performance IV. New York: Academic Press. pp. 395–409.

- Groves PS, Bunch JL, Cram E, Farag A, Manges K, Perkhounkova Y, Scott-Cawiezell J (November 2017). "Priming Patient Safety Through Nursing Handoff Communication: A Simulation Pilot Study". Western Journal of Nursing Research. 39 (11): 1394–1411. doi:10.1177/0193945916673358. PMID 28322631. S2CID 32696412.

- Cermak LS, Talbot N, Chandler K, Wolbarst LR (1985). "The perceptual priming phenomenon in amnesia". Neuropsychologia. 23 (5): 615–22. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(85)90063-6. PMID 4058707. S2CID 30545942.

- Shimamura AP, Squire LR (1984). "Paired-associate learning and priming effects in amnesia: a neuropsychological approach". J. Exp. Psychol. 113 (4): 556–570. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.554.414. doi:10.1037/0096-3445.113.4.556.

- Blaxton TA (September 1992). "Dissociations among memory measures in memory-impaired subjects: evidence for a processing account of memory". Memory & Cognition. 20 (5): 549–62. doi:10.3758/BF03199587. PMID 1453972.

- Graf P, Squire LR, Mandler G (January 1984). "The information that amnesic patients do not forget". Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition. 10 (1): 164–78. doi:10.1037/0278-7393.10.1.164. PMID 6242734.

- "Aphasia". The British Medical Journal. 2 (296): 258–261. 1866. ISSN 0007-1447. JSTOR 25205881.

- Carlesimo GA, Oscar-Berman M (June 1992). "Memory deficits in Alzheimer's patients: a comprehensive review". Neuropsychology Review. 3 (2): 119–69. doi:10.1007/BF01108841. PMID 1300219. S2CID 19548915.

- Schacter DL, McGlynn SM, Milberg WP, Church BA (1993). "Spared priming despite impaired comprehension: implicit memory in a case of word meaning deafness". Neuropsychology. 7 (2): 107–118. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.7.2.107.

- Geva A, Moscovitch M, Leach L (April 1997). "Perceptual priming of proper names in young and older normal adults and a patient with prosopanomia". Neuropsychology. 11 (2): 232–42. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.11.2.232. PMID 9110330.

- Li L, Miller EK, Desimone R (June 1993). "The representation of stimulus familiarity in anterior inferior temporal cortex". Journal of Neurophysiology. 69 (6): 1918–29. doi:10.1152/jn.1993.69.6.1918. PMID 8350131. S2CID 6482631.

- Gruber T, Müller MM (May 2002). "Effects of picture repetition on induced gamma band responses, evoked potentials, and phase synchrony in the human EEG". Brain Research. Cognitive Brain Research. 13 (3): 377–92. doi:10.1016/S0926-6410(01)00130-6. PMID 11919002.

- Squire LR, Ojemann JG, Miezin FM, Petersen SE, Videen TO, Raichle ME (March 1992). "Activation of the hippocampus in normal humans: a functional anatomical study of memory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 89 (5): 1837–41. Bibcode:1992PNAS...89.1837S. doi:10.1073/pnas.89.5.1837. PMC 48548. PMID 1542680.

- Wig GS, Grafton ST, Demos KE, Kelley WM (September 2005). "Reductions in neural activity underlie behavioral components of repetition priming". Nature Neuroscience. 8 (9): 1228–33. doi:10.1038/nn1515. PMID 16056222. S2CID 470957.

- Moldakarimov S, Bazhenov M, Sejnowski TJ (March 2010). "Perceptual priming leads to reduction of gamma frequency oscillations". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 107 (12): 5640–5. Bibcode:2010PNAS..107.5640M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907525107. PMC 2851786. PMID 20212165.

- Demb JB, Desmond JE, Wagner AD, Vaidya CJ, Glover GH, Gabrieli JD (September 1995). "Semantic encoding and retrieval in the left inferior prefrontal cortex: a functional MRI study of task difficulty and process specificity". The Journal of Neuroscience. 15 (9): 5870–8. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-09-05870.1995. PMC 6577672. PMID 7666172.

- Gabrieli JD, Poldrack RA, Desmond JE (February 1998). "The role of left prefrontal cortex in language and memory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 95 (3): 906–13. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95..906G. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.3.906. PMC 33815. PMID 9448258.

- Dehaene S, Naccache L, Le Clec'H G, Koechlin E, Mueller M, Dehaene-Lambertz G, van de Moortele PF, Le Bihan D (October 1998). "Imaging unconscious semantic priming" (PDF). Nature. 395 (6702): 597–600. Bibcode:1998Natur.395..597D. doi:10.1038/26967. PMID 9783584. S2CID 4373890. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 6, 2011.

- Bargh JA, Chen M, Burrows L (August 1996). "Automaticity of social behavior: direct effects of trait construct and stereotype-activation on action". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 71 (2): 230–44. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.318.3898. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.230. PMID 8765481.

- (see Ironic process theory for a more in-depth discussion of this phenomenon)

- Bargh JA, Williams EL (February 2006). "The Automaticity of Social Life". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 15 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2006.00395.x. PMC 2435044. PMID 18568084.

- Williams LE, Bargh JA (October 2008). "Experiencing physical warmth promotes interpersonal warmth". Science. 322 (5901): 606–7. Bibcode:2008Sci...322..606W. doi:10.1126/science.1162548. PMC 2737341. PMID 18948544.

- Cox WT, Abramson LY, Devine PG, Hollon SD (September 2012). "Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Depression: The Integrated Perspective". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 7 (5): 427–49. doi:10.1177/1745691612455204. PMID 26168502. S2CID 1512121.

- Pashler H, Coburn N, Harris CR (2012). "Priming of social distance? Failure to replicate effects on social and food judgments". PLOS ONE. 7 (8): e42510. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...742510P. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0042510. PMC 3430642. PMID 22952597.

- PsychFileDrawer, (2013). Replicability of Social and goal priming findings.

- Rajain P (September 2016). "Sensory Marketing Aspects: Priming, Expectations, Crossmodal Correspondences & More". Vikalpa. 41 (3): 264–6. doi:10.1177/0256090916652045.

- Meyer DE (August 2014). "Semantic priming well established". Science. 345 (6196): 523. Bibcode:2014Sci...345..523M. doi:10.1126/science.345.6196.523-b. PMID 25082691.

- Yong E. "Replication studies: Bad copy". Nature. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- Kahneman D. "A proposal to deal with questions about priming effects" (PDF). Nature. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- "Adversarial Collaboration: An EDGE Lecture by Daniel Kahneman | Edge.org". www.edge.org. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- Yong, Ed (March 10, 2012). "A failed replication draws a scathing personal attack from a psychology professor". Discover Magazine. Retrieved October 12, 2012.