Sequel

A sequel is a work of literature, film, theatre, television, music or video game that continues the story of, or expands upon, some earlier work. In the common context of a narrative work of fiction, a sequel portrays events set in the same fictional universe as an earlier work, usually chronologically following the events of that work.[1]

In many cases, the sequel continues elements of the original story, often with the same characters and settings. A sequel can lead to a series, in which key elements appear repeatedly. Although the difference between more than one sequel and a series is somewhat arbitrary, it is clear that some media franchises have enough sequels to become a series, whether originally planned as such or not.

Sequels are attractive to creators and to publishers because there is less risk involved in returning to a story with known popularity rather than developing new and untested characters and settings. Audiences are sometimes eager for more stories about popular characters or settings, making the production of sequels financially appealing.[2]

In film, sequels are very common. There are many name formats for sequels. Sometimes, they either have unrelated titles or have a letter added on the end. More commonly, they have numbers at the end or have added words on the end. It is also common for a sequel to have a variation of the original title or have a subtitle. In the 1930s, many musical sequels had the year included in the title. Sometimes sequels are released with different titles in different countries, because of the perceived brand recognition. There are several ways that subsequent works can be related to the chronology of the original. Various neologisms have been coined to describe them.

Classifications

The most common approach is for the events of the second work to directly follow the events of the first one, either resolving remaining plot threads or introducing a new conflict to drive the events of the second story. This is often called a direct sequel.

A legacy sequel is a work that follows the continuity of the original work(s), but takes place further along the timeline, often focusing on new characters with the original ones still present in the plot.[3][4][5] Legacy sequels are sometimes also direct sequels that ignore previous installments entirely, effectively retconning preceding events. Superman Returns, Halloween, Cobra Kai, Blade Runner 2049, the Star Wars sequel trilogy, Ghostbusters: Afterlife, Terminator: Dark Fate, Top Gun: Maverick and the Jurassic World Trilogy are examples of legacy sequels.

A standalone sequel is a work set in the same universe, yet has very little, if any, inspiration from its predecessor in terms of its narrative, and can stand on its own without a thorough understanding of the series. Home Alone 3, Species - The Awakening, Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides, The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift, Mad Max: Fury Road, The SpongeBob Movie: Sponge Out of Water, Spirit Untamed, Space Jam: A New Legacy, The Suicide Squad, and Ghost Rider: Spirit of Vengeance are examples of standalone sequels.[6][7]

A spiritual sequel is a work inspired by its predecessor. It shares the same styles, genres and elements as its predecessor, but has no direct connection to it at all. Most spiritual sequels are also set in different universes from their predecessors, and some spiritual sequels aren't even a part of their predecessor's franchise, making them non-franchise sequels. Examples of spiritual sequels in film include 10 Cloverfield Lane, a spiritual sequel to the film Cloverfield, and Mute, a spiritual sequel to the film Moon. The video game Deltarune is also considered a spiritual sequel to Undertale, a similar video game.

A sequel to the first sequel might be referred to as a "third installment", a threequel, or a second sequel.[8][9] Batman Forever, Captain America: Civil War, The Matrix Revolutions, and How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World are examples of "third installment" sequels.

Parallels, paraquels, or sidequels are stories that run at the same point in time as the original story.[10][11]

Midquel is a term used to refer to works which take place between events. Types include interquels and intraquels.[12] An interquel is a story that takes place in between two previously published or released stories. For example, if 'movie C' is an interquel of 'movies A' and 'B', the events of 'movie C' take place after the events of 'movie A', but before the events of 'movie B'. An examples can include Rogue One: A Star Wars Story of Star Wars and some films of The Fast and the Furious franchise. An intraquel, on the other hand, is a work which focuses on events within a previous work. An examples can include Bambi 2 and Black Widow.[13][14][15]

Relatives

Alongside sequels, there are also other types of continuation or inspiration of a previous work.

A prequel is an installment that is made following the original product which portrays events occurring chronologically before those of the original work.[16] Although its name is based on the word sequel, prequels are usually spin-offs, not true sequels. Some prequels are also a part of the main series, making them prequel/sequel hybrids or prequel sequels. An example of this would be Better Call Saul, taking place mainly before Breaking Bad but also having some scenes after and during it.

A spin-off is a work that is not a sequel to any previous works, but is set in the same universe. It is a separate work-on-its-own in the same franchise as the series of other works. Spin-offs are often focused on one or more of the minor characters from the other work or new characters in the same universe as the other work. The Scorpion King, Planes, Minions, Hobbs & Shaw and Lightyear are examples of spin-off movies while Star Trek: The Next Generation and CSI: NY are examples of spin-off television series.

A crossover is a work where two previous works from different franchises are meeting in the same universe. Alien vs. Predator, Freddy vs. Jason, Boa vs. Python and Lake Placid vs. Anaconda are examples of a crossover film.

A reboot is a start over from a previous work. It could either be a film set in a new universe resembling the old one or it could be a regular spin-off film that starts a new film series. Reboots are usually a part of the same media franchise as the previous work(s), but not always. Batman Begins, Casino Royale, Star Trek, Børning, Man of Steel and Terminator: Genisys are examples of reboot films.

History

In The Afterlife of a Character, David Brewer describes a reader's desire to "see more", or to know what happens next in the narrative after it has ended.[17]

Sequels of the novel

The origin of the sequel as it is conceived in the 21st century developed from the novella and romance traditions in a slow process that culminated towards the end of the 17th century.

The substantial shift toward a rapidly growing print culture and the rise of the market system by the early 18th-century meant that an author's merit and livelihood became increasingly linked to the number of copies of a work he or she could sell. This shift from a text-based to an author-centered reading culture[18] led to the "professionalization" of the author – that is, the development of a "sense of identity based on a marketable skill and on supplying to a defined public a specialized service it was demanding."[19] In one sense, then, sequels became a means to profit further from previous work that had already obtained some measure of commercial success.[20] As the establishment of a readership became increasingly important to the economic viability of authorship, sequels offered a means to establish a recurring economic outlet.

In addition to serving economic profit, the sequel was also used as a method to strengthen an author's claim to his literary property. With weak copyright laws and unscrupulous booksellers willing to sell whatever they could, in some cases the only way to prove ownership of a text was to produce another like it. Sequels in this sense are rather limited in scope, as the authors are focused on producing "more of the same" to defend their "literary paternity".[19] As is true throughout history, sequels to novels provided an opportunity for authors to interact with a readership. This became especially important in the economy of the 18th century novel, in which authors often maintained readership by drawing readers back with the promise of more of what they liked from the original. With sequels, therefore, came the implicit division of readers by authors into the categories of "desirable" and "undesirable"—that is, those who interpret the text in a way unsanctioned by the author. Only after having achieved a significant reader base would an author feel free to alienate or ignore the "undesirable" readers.[19]

This concept of "undesirable" readers extends to unofficial sequels with the 18th century novel. While in certain historical contexts unofficial sequels were actually the norm (for an example, see Arthurian literature), with the emphasis on the author function that arises in conjunction with the novel many authors began to see these kinds of unauthorized extensions as being in direct conflict with authorial authority. In the matter of Don Quixote (an early novel, perhaps better classified as a satirical romance), for example, Cervantes disapproved of Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda's use of his characters in Second Volume of the Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha, an unauthorized sequel. In response, Cervantes very firmly kills the protagonist at the end of the Second Part to discourage any more such creative liberties.[21] Another example is Samuel Richardson, an 18th-century author who responded particularly strongly against the appropriation of his material by unauthorized third parties. Richardson was extremely vocal in his disapproval of the way the protagonist of his novel Pamela was repeatedly incorporated into unauthorized sequels featuring particularly lewd plots. The most famous of these is Henry Fielding's parody, entitled Shamela.[22]

In To Renew Their Former Acquaintance: Print, Gender, and Some Eighteenth Century Sequels, Betty Schellenberg theorizes that whereas for male writers in the 18th century sequels often served as "models of paternity and property", for women writers these models were more likely to be seen as transgressive. Instead, the recurring readership created by sequels let female writers function within the model of "familiar acquaintances reunited to enjoy the mutual pleasures of conversation", and made their writing an "activity within a private, non-economic sphere". Through this created perception women writers were able to break into the economic sphere and "enhance their professional status" through authorship.[19]

Dissociated from the motives of profit and therefore unrestrained by the need for continuity felt by male writers, Schellenberg argues that female-authored sequel fiction tended to have a much broader scope. He says that women writers showed an "innovative freedom" that male writers rejected to "protect their patrimony". For example, Sarah Fielding's Adventures of David Simple and its sequels Familiar Letters between the Principal Characters in David Simple and David Simple, Volume the Last are extremely innovative and cover almost the entire range of popular narrative styles of the 18th century.[23]

Video games

As the cost of developing a triple-A video game has risen,[24][25][26] sequels have become increasingly common in the video game industry.[27] Today, new installments of established brands make up much of the new releases from mainstream publishers and provide a reliable source of revenue, smoothing out market volatility.[28] Sequels are often perceived to be safer than original titles because they can draw from the same customer base, and generally keep to the formula that made the previous game successful.

Media franchises

In some cases, the characters or the settings of an original film or video game become so valuable that they develop into a series, lately referred to as a media franchise. Generally, a whole series of sequels is made, along with merchandising. Multiple sequels are often planned well in advance, and actors and directors may sign extended contracts to ensure their participation. This can extend into a series/ franchise's initial production's plot to provide story material to develop for sequels called sequel hooks.

Box office

Movie sequels do not always do as well at the box office as the original, but they tend to do better than non-sequels, according to a study in the July 2008 issue of the Journal of Business Research. The shorter the period between releases, the better the sequel does at the box office. Sequels also show a faster drop in weekly revenues relative to non-sequels.[29]

Sequels in other media

Sequels are most often produced in the same medium as the previous work (e.g. a film sequel is usually a sequel to another film). Producing sequels to a work in another medium has recently become common, especially when the new medium is less costly or time-consuming to produce.

A sequel to a popular but discontinued television series may be produced in another medium, thereby bypassing whatever factors led to the series' cancellation.

Some highly popular movies and television series have inspired the production of multiple novel sequels, sometimes rivaling or even dwarfing the volume of works in the original medium.

For example, the 1956 novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians, its 1961 animated adaptation and that film's 1996 live-action remake each have a sequel unrelated to the other sequels: respectively The Starlight Barking (1967), 101 Dalmatians II: Patch's London Adventure (2003, direct to video) and 102 Dalmatians (2000).

Unofficial sequels

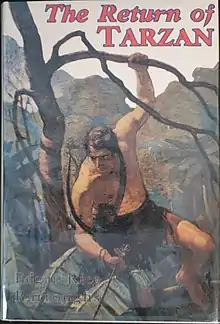

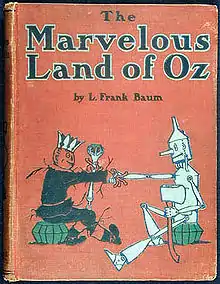

Sometimes sequels are produced without the consent of the creator of the original work. These may be dubbed unofficial, informal, unauthorized, or illegitimate sequels. In some cases, the work is in the public domain, and there is no legal obstacle to producing sequels. An example would be books and films serving as sequels to the book The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, which is in the public domain (as opposed to its 1939 film adaptation). In other cases, the original creator or their heirs may assert copyrights, and challenge the creators of the sequels.

Literary

- Old Friends and New Fancies: An Imaginary Sequel to the Novels of Jane Austen (1913) is a novel by Sybil G. Brinton that is generally acknowledged to be the first sequel to the works of Jane Austen and as such the first piece of Austen fan fiction.[30][31]

- Porto Bello Gold (1924), a prequel by A. D. Howden Smith to Treasure Island that was written with explicit permission from Stevenson's executor, tells the origin of the buried treasure and recasts many of Stevenson's pirates in their younger years, giving the hidden treasure some Jacobite antecedents not mentioned in the original.[32]

- Back to Treasure Island (1935) is a sequel by H. A. Calahan, the introduction of which argues that Robert Louis Stevenson wanted to write a continuation of the story.

- Heidi Grows Up (a.k.a. Heidi Grows Up: A Sequel to Heidi) is a 1938 novel and sequel to Johanna Spyri's 1881 novel Heidi, written by Spyri's French and English translator, Charles Tritten, after a three-decade long period of pondering what to write, since Spyri's death gave no sequel of her own.[33][34]

- Manly Wade Wellman and his son Wade Wellman wrote Sherlock Holmes' War of the Worlds (1975) which describes Sherlock Holmes's adventures during the Martian occupation of London. This version uses Wells' short story "The Crystal Egg" as a prequel (with Holmes being the man who bought the egg at the end) and includes a crossover with Arthur Conan Doyle's Professor Challenger stories. Among many changes the Martians are changed into simple vampires, who suck and ingest human blood.[35]

- In The Space Machine (1976) Christopher Priest presents both a sequel and prequel to The War of the Worlds (due to time travel elements), which also integrates the events of The Time Machine.[36]

- György Dalos wrote the novel 1985 that was intended as a direct sequel to Orwell's work.

- Alice Through the Needle's Eye (1984) by Gilbert Adair, a sequel to Lewis Carroll's Alice in Wonderland books.[37]

- The novelist Angela Carter was working on a sequel to Jane Eyre at the time of her death in 1992. This was to have been the story of Jane's stepdaughter Adèle Varens and her mother Céline. Only a synopsis survives.[38]

- Mrs. Rochester: A Sequel to Jane Eyre (1997) by Hilary Bailey.

- The Last Ringbearer (Russian: Последний кольценосец, Posledniy kol'tsenosets) (1999) is a fantasy book by Russian author Kirill Eskov. It is an alternative account of, and an informal sequel to, the events of J.R.R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings.[39]

See also

- Cliffhanger

- Crossover (fiction)

- Film series

- Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd.

- List of video game franchises

- List of film sequels by box-office performance

- Prequel

- List of prequels

- Reboot (fiction)

- Remake

- Shared universe

- Spin-off (media)

- Spiritual successor

- Standalone film

- Tetralogy

- Trilogy

References

- Fabrikant, Geraldine (March 12, 1991). "Sequels of Hit Films Now Often Loser". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-08-09.

- Rosen, David (June 15, 2011). "Creative Bankruptcy". Call It Like I See It. Archived from the original on December 3, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- "6 Films That Are Waiting for Their Legacy Sequels". 4 August 2016.

- "Do legacy sequels fail if they pander to the fans?". 30 December 2016.

- "Creed 2 Loses Sylvester Stallone as Director". 12 December 2017.

- Michael Andre-Driussi (1 August 2008). Lexicon Urthus, Second Edition. Sirius Fiction. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-9642795-1-3. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- "Five Films Show How 2008 Redefined the Movies". Cinematic Slant. 14 August 2018. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- John Kenneth Muir (2013). Horror Films of the 1980s. McFarland. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-7864-5501-0. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- Soanes, Stevenson (2008). Concise Oxford English dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 1501. ISBN 978-0199548415.

- "What is a Paraquel?", The Storyteller's Scroll; Sunday, March 27, 2011

- Mark J.P. Wolf, Building Imaginary Worlds: The Theory and History of Subcreation; 210

- Wolf, Mark J.P. (2017). The Routledge Companion to Imaginary Worlds. Taylor & Francis. pp. 82–. ISBN 978-1-317-26828-4.

- William D. Crump, How the Movies Saved Christmas: 228 Rescues from Clausnappers, Sleigh Crashes, Lost Presents and Holiday Disasters; 19

- Jack Zipes; The Enchanted Screen: The Unknown History of Fairy-Tale Films

- Mark J.P. Wolf; The Routledge Companion to Imaginary Worlds

- Silverblatt, Art (2007). Genre Studies in Mass Media: A Handbook. M. E. Sharpe. p. 211. ISBN 9780765616708.

Prequels focus on the action that took place before the original narrative. For instance, in Star Wars: Episode III – Revenge of the Sith the audience learns about how Darth Vader originally became a villain. A prequel assumes that the audience is familiar with the original—the audience must rework the narrative so that they can understand how the prequel leads up to the beginning of the original.

- Brewer, David A. The Afterlife of Character, 1726–1825. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2005. Print.

-

Schellenberg, Betty A. (2007). "The Measured Lines of the Copyist: Sequels, Reviews, and the Discourse of Authorship in England, 1749–1800". In Taylor Bourdeau, Debra; Kraft, Elizabeth (eds.). On Second Thought: Updating the Eighteenth-century Text. University of Delaware Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780874139754. Retrieved 2014-11-14.

Of particular interest to me in this essay is the shift from a text-based to an author-based culture, accompanied by a developing elevation of the original author over the imitative one.

- Schellenberg, Betty A. "'To Renew Their Former Acquaintance': Print, Gender, and Some Eighteenth-Century Sequels." Part Two: Reflections on the Sequel (Theory / Culture). Ed. Paul Budra and Betty A. Schellenberg. New York: University of Toronto, 1998. Print.

- Budra, Paul, and Betty Schellenberg. "Introduction." Part Two: Reflections on the Sequel (Theory / Culture). New York: University of Toronto, 1998. Print.

- Riley, E.C. "Three Versions of Don Quixote". The Modern Language Review 68.4 (173). JSTOR. Web.

- Brewer, David A. The Afterlife of Character, 1726–1825. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2005. Print.

- Michie, Allen. "Far From Simple: Sarah Fielding's Familiar Letters and the Limits of the Eighteenth-Century Sequel" in Second Thought, Edited by Bourdeau and Kraft. Cranbury, NJ: Rosemont, 2007. Print.

- Koster, Raph (January 23, 2018). "The cost of games". VentureBeat. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

The trajectory line for triple-A games ... goes up tenfold every 10 years and has since at least 1995 or so ...

- Takatsuki, Yo (December 27, 2007). "Cost headache for game developers". BBC News.

- Mattas, Jeff. "Video Game Development Costs Continue to Rise in Face of Nearly 12K Layoffs Since '08". Shacknews.

- Taub, Eric (September 20, 2004). "In Video Games, Sequels Are Winners". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- Richtel, Matt (August 8, 2005). "Relying on Video Game Sequels". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2019.

- Newswise: Researchers Investigate Box Office Impact Vs. Original Movie Retrieved on June 19, 2008.

- "Austen mashups are nothing new to Janeites". The Daily Dot. 23 July 2012.

- Morrison, Ewan (13 August 2012). "In the beginning, there was fan fiction: from the four gospels to Fifty Shades". The Guardian.

- "Piratical prequels".

- "Heidi Grows Up" - foreword, by Charles Tritten

- "Heidi has a secret past: she sneaked in over the border".

- "War of the Worlds gets a sequel 119 years on – but what about all the unofficial ones?". The Guardian. 8 December 2015.

- "Steampunk". The A.V. Club. 16 July 2009.

- Fuller, John (5 May 1985). "LEWIS CARROLL IS STILL DEAD (Published 1985)". The New York Times.

- Susannah Clapp (2006-01-29). "Theatre: Nights at the Circus | The Observer". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- Smith, Kevin (23 February 2011). "One ring to rule them all?". Scholarly Communications @ Duke.

Further reading

- Henderson, Stuart (2017). The Hollywood Sequel: History & Form, 1911-2010. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84457-843-6.

- Jess-Cooke, Carolyn (2012). Film Sequels. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-8947-7.

- Jess-Cooke, Carolyn; Verevis, Constantine (2012). Second Takes: Critical Approaches to the Film Sequel. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-3031-7.