7 World Trade Center

7 World Trade Center (7 WTC, WTC-7, or Tower 7) refers to two buildings that have existed at the same location within the World Trade Center site in Lower Manhattan, New York City. The original structure, part of the original World Trade Center, was completed in 1987 and was destroyed in the September 11 attacks in 2001. The current structure opened in May 2006. Both buildings were developed by Larry Silverstein, who holds a ground lease for the site from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.

| 7 World Trade Center | |

|---|---|

The new 7 World Trade Center from the southwest (2008) | |

| |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Office |

| Location | 250 Greenwich Street Manhattan, New York City 10006, United States |

| Coordinates | 40.7133°N 74.0120°W |

| Construction started | May 7, 2002[1] |

| Completed | 2006 |

| Opened | May 23, 2006 |

| Height | |

| Architectural | 743 ft (226 m)[2] |

| Roof | 741 ft (226 m)[3] |

| Top floor | 679 ft (207 m)[2] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 52[3][4] |

| Floor area | 1,681,118 sq ft (156,181 m2)[2] |

| Lifts/elevators | 29[2] |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | David Childs of SOM[2] |

| Developer | Silverstein Properties[2][4] |

| Structural engineer | WSP Cantor Seinuk[2] |

| Main contractor | Tishman Construction |

| Website | |

| 7 World Trade Center, wtc.com | |

| References | |

| [2] | |

The original 7 World Trade Center was 47 stories tall, clad in red granite masonry, and occupied a trapezoidal footprint. An elevated walkway spanning Vesey Street connected the building to the World Trade Center plaza. The building was situated above a Consolidated Edison power substation, which imposed unique structural design constraints. When the building opened in 1987, Silverstein had difficulties attracting tenants. Salomon Brothers signed a long-term lease in 1988 and became the anchor tenant of 7 WTC.

On September 11, 2001, the structure was substantially damaged by debris when the nearby North Tower of the World Trade Center collapsed. The debris ignited fires on multiple lower floors of the building, which continued to burn uncontrolled throughout the afternoon. The building's internal fire suppression system lacked water pressure to fight the fires. The collapse began when a critical internal column buckled and triggered cascading failure of nearby columns throughout, which was first visible from the exterior with the crumbling of a rooftop penthouse structure at 5:20:33 pm. This initiated progressive collapse of the entire building at 5:21:10 pm, according to FEMA,[5]: 23 while the 2008 NIST study placed the final collapse time at 5:20:52 pm.[6]: 19, 21, 50–51 The collapse made the old 7 World Trade Center the first steel skyscraper known to have collapsed primarily due to uncontrolled fires.[7][8]

Construction of the new 7 World Trade Center began in 2002 and was completed in 2006. The building is 52 stories tall (plus one underground floor), making it the 28th-tallest in New York.[2][3][4] It is built on a smaller footprint than the original, and is bounded by Greenwich, Vesey, Washington, and Barclay Streets on the east, south, west, and north, respectively. A small park across Greenwich Street occupies space that was part of the original building's footprint. The current building's design emphasizes safety, with a reinforced concrete core, wider stairways, and thicker fireproofing on steel columns. It also incorporates numerous green design features. The building was the first commercial office building in New York City to receive the U.S. Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification, where it won a gold rating. It was also one of the first projects accepted to be part of the council's pilot program for Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design – Core and Shell Development (LEED-CS).[9]

Original building (1987–2001)

Design and layout

_3D_diagram_showing_relation_of_trusses_and_transfer_girders.svg.png.webp)

The original 7 World Trade Center was a 47-story building, designed by Emery Roth & Sons, with a red granite facade. The building was 610 feet (190 m) tall, with a trapezoidal footprint that was 330 ft (100 m) long and 140 ft (43 m) wide.[10][11] Tishman Realty & Construction managed construction of the building.[10] The ground-breaking ceremony was hosted on October 2, 1984.[12] The building opened in May 1987, becoming the seventh structure of the World Trade Center.[13]

7 World Trade Center was constructed above a two-story Con Edison substation that had been located on the site since 1967.[14][12] The substation had a caisson foundation designed to carry the weight of a future building of 25 stories containing 600,000 sq ft (56,000 m2).[15] However, the final design for 7 World Trade Center was for a much larger building than originally planned when the substation was built.[16]: xxxviii The structural design of 7 World Trade Center therefore included a system of gravity column transfer trusses and girders, located between floors 5 and 7, to transfer loads to the smaller foundation.[6]: 5 Existing caissons installed in 1967 were used, along with new ones, to accommodate the building. The 5th floor functioned as a structural diaphragm, providing lateral stability and distribution of loads between the new and old caissons. Above the 7th floor, the building's structure was a typical tube-frame design, with columns in the core and on the perimeter, and lateral loads resisted by perimeter moment frames.[15]

A shipping and receiving ramp, which served the entire World Trade Center complex, occupied the eastern quarter of the 7 World Trade Center footprint. The building was open below the 3rd floor, providing space for truck clearance on the shipping ramp.[15] The spray-on fireproofing for structural steel elements was gypsum-based Monokote, which had a two-hour fire rating for steel beams, girders and trusses, and a three-hour rating for columns.[5]: 11

Mechanical equipment was installed on floors four through seven, including 12 transformers on the 5th floor. Several emergency generators installed in the building were used by the New York City Office of Emergency Management, Salomon Smith Barney, and other tenants.[5]: 13 In order to supply the generators, 24,000 gallons (91,000 L) of diesel fuel were stored below ground level.[17] Diesel fuel distribution components were located at ground level, up to the ninth floor.[18]: 35 After the World Trade Center bombings of February 26, 1993, New York City mayor Rudy Giuliani decided to situate the emergency command center and associated fuel tanks at 7 World Trade Center. Although this decision was criticized in light of the events of 9/11, the fuel in the building is today not believed to have contributed to the collapse of the building.[19][20]: 2 The roof of the building included a small west penthouse and a larger east mechanical penthouse.[14]

Each floor had 47,000 sq ft (4,400 m2) of rentable office space, which made the building's floor plans considerably larger than most office buildings in the city.[21] In all, 7 World Trade Center had 1,868,000 sq ft (173,500 m2) of office space.[5]: 1 Two pedestrian bridges connected the main World Trade Center complex, across Vesey Street, to the third floor of 7 World Trade Center. The lobby of 7 World Trade Center held three murals by artist Al Held: The Third Circle, Pan North XII, and Vorces VII.[22]

Tenants

.jpg.webp)

In June 1986, before construction was completed, developer Larry Silverstein signed Drexel Burnham Lambert as a tenant to lease the entire 7 World Trade Center building for $3 billion over a term of 30 years.[23] In December 1986, after the Boesky insider-trading scandal, Drexel Burnham Lambert canceled the lease, leaving Silverstein to find other tenants.[24] Spicer & Oppenheim agreed to lease 14 percent of the space, but for more than a year, as Black Monday and other factors adversely affected the Lower Manhattan real estate market, Silverstein was unable to find tenants for the remaining space. By April 1988, he had lowered the rent and made other concessions.[25]

In November 1988, Salomon Brothers withdrew from plans to build a large new complex at Columbus Circle in Midtown, instead agreeing to a 20-year lease for the top 19 floors of 7 World Trade Center.[26] The building was extensively renovated in 1989 to accommodate Salomon Brothers, and 7 World Trade Center alternatively became known as the Salomon Brothers building.[27] Most of the three existing floors were removed as tenants continued to occupy other stories, and more than 350 tons (U.S.) of steel were added to construct three double-height trading floors. Nine diesel generators were installed on the 5th floor as part of a backup power station. "Essentially, Salomon is constructing a building within a building – and it's an occupied building, which complicates the situation", said a district manager of Silverstein Properties.[27] According to Larry Silverstein, the unusual task was possible because it could allow "entire portions of floors to be removed without affecting the building's structural integrity, on the assumption that someone might need double-height floors."[27]

At the time of the September 11, 2001, attacks, Salomon Smith Barney was by far the largest tenant in 7 World Trade Center, occupying 1,202,900 sq ft (111,750 m2) (64 percent of the building) which included floors 28–45.[5]: 2 [28] Other major tenants included ITT Hartford Insurance Group (122,590 sq ft/11,400 m2), American Express Bank International (106,117 sq ft/9,900 m2), Standard Chartered Bank (111,398 sq ft/10,350 m2), and the Securities and Exchange Commission (106,117 sq ft/9,850 m2).[28] Smaller tenants included the Internal Revenue Service Regional Council (90,430 sq ft/8,400 m2) and the United States Secret Service (85,343 sq ft/7,900 m2).[28] The smallest tenants included the New York City Office of Emergency Management,[29] National Association of Insurance Commissioners, Federal Home Loan Bank of New York, First State Management Group Inc., Provident Financial Management, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service.[28] The Department of Defense (DOD) and Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) shared the 25th floor with the IRS.[5]: 2 (The clandestine CIA office was revealed only after the 9/11 attacks.)[30] Floors 46–47 were mechanical floors, as were the bottom six floors and part of the seventh floor.[5]: 2 [30]

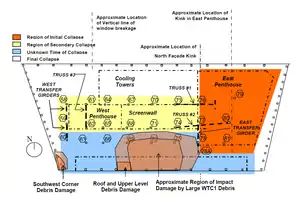

9/11 and collapse

Collapse

As the North Tower collapsed on September 11, 2001, heavy debris hit 7 World Trade Center, damaging the south face of the building[31]: 18 (PDF p. 22) and starting fires that continued to burn throughout the afternoon.[6]: 16, 18 The collapse also caused damage to the southwest corner between floors 7 and 17 and on the south face between Floor 44 and the roof; other possible structural damage included a large vertical gash near the center of the south face between Floors 24 and 41.[6]: 17 The building was equipped with a sprinkler system, but had many single-point vulnerabilities for failure: the sprinkler system required manual initiation of the electrical fire pumps, rather than being a fully automatic system; the floor-level controls had a single connection to the sprinkler water riser, and the sprinkler system required some power for the fire pump to deliver water.[32]: 11 Additionally, water pressure was low, with little or no water to feed sprinklers.[33]: 23–30

After the North Tower collapsed, some firefighters entered 7 World Trade Center to search the building. They attempted to extinguish small pockets of fire, but low water pressure hindered their efforts.[34] Over the course of the day, fires burned out of control on several floors of 7 World Trade Center, the flames visible on the east side of the building.[35] During the afternoon, the fire was also seen on floors 6–10, 13–14, 19–22, and 29–30.[31]: 24 (PDF p. 28) In particular, the fires on floors 7 through 9 and 11 through 13 continued to burn out of control during the afternoon.[7] At approximately 2:00 pm, firefighters noticed a bulge in the southwest corner of 7 World Trade Center between the 10th and 13th floors, a sign that the building was unstable and might collapse.[36] During the afternoon, firefighters also heard creaking sounds coming from the building.[37] Around 3:30 pm, FDNY Chief of Operations Daniel A. Nigro decided to halt rescue operations, surface removal, and searches along the surface of the debris near 7 World Trade Center and evacuate the area due to concerns for the safety of personnel.[38]

The fire expanded the girders of the building, causing some to collapse. This led to the northeast corner core column (Column 79), which was especially large, to buckle below the 13th floor. This caused the floors above it to collapse to the transfer floor at the fifth level. The structure also developed cracks in the facade just before the entire building started to fall.[6]: 21 [39] According to FEMA, this collapse started at 5:20:33 pm EDT when the east mechanical penthouse started crumbling.[5]: 23 [40] Differing times are given as to what time the building completely collapsed:[40] at 5:21:10 pm EDT according to FEMA,[5]: 23 and at 5:20:52 pm EDT according to NIST.[6]: 19, 21, 50–51

There were no casualties associated with the collapse.[39] NIST found no evidence to support conspiracy theories such as the collapse being the result of explosives; it found that a combination of factors including physical damage, fire, and the building's unusual construction set off a chain-reaction collapse.[41]

Reports

In May 2002, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) issued a report on the collapse based on a preliminary investigation conducted jointly with the Structural Engineering Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers under the leadership of Dr. W. Gene Corley, P.E. FEMA made preliminary findings that the collapse was not primarily caused by actual impact damage from the collapse of 1 WTC and 2 WTC but by fires on multiple stories ignited by debris from the other two towers that continued burning unabated due to lack of water for sprinklers or manual firefighting. The report did not reach conclusions about the cause of the collapse and called for further investigation.[20]: 3

Subsequently, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) was authorized to lead an investigation into the structural failure and collapse of the World Trade Center Twin Towers and 7 World Trade Center.[7] The investigation, led by Dr S. Shyam Sunder, drew upon in-house technical expertise as well as the knowledge of several outside private institutions, including the Structural Engineering Institute of the American Society of Civil Engineers (SEI/ASCE); the Society of Fire Protection Engineers (SFPE); the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA); the American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC); the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (CTBUH); and the Structural Engineers Association of New York (SEAoNY).[42]

The bulk of the investigation of 7 World Trade Center was delayed until after reports were completed on the Twin Towers.[7] In the meantime, NIST provided a preliminary report about 7 WTC in June 2004, and thereafter released occasional updates on the investigation.[31] According to NIST, the investigation of 7 World Trade Center was delayed for a number of reasons, including that NIST staff who had been working on 7 World Trade Center were assigned full-time from June 2004 to September 2005 to work on the investigation of the collapse of the Twin Towers.[43] In June 2007, Shyam Sunder explained,

We are proceeding as quickly as possible while rigorously testing and evaluating a wide range of scenarios to reach the most definitive conclusion possible. The 7 WTC investigation is in some respects just as challenging, if not more so than the study of the towers. However, the current study does benefit greatly from the significant technological advances achieved and lessons learned from our work on the towers.[44]

In November 2008, NIST released its final report on the causes of the collapse of 7 World Trade Center.[6] This followed NIST's August 21, 2008, draft report which included a period for public comments,[7] and was followed in 2012 by a peer-reviewed summary in the Journal of Structural Engineering.[45] In its investigation, NIST utilized ANSYS to model events leading up to collapse initiation and LS-DYNA models to simulate the global response to the initiating events.[46]: 6–7 NIST determined that diesel fuel did not play an important role, nor did the structural damage from the collapse of the Twin Towers or the transfer elements (trusses, girders, and cantilever overhangs). The lack of water to fight the fire was an important factor. The fires burned out of control during the afternoon, causing floor beams near column 79 to expand and push a key girder off its seat, triggering the floors to fail around column 79 on Floors 8 to 14. With a loss of lateral support across nine floors, column 79 buckled – pulling the east penthouse and nearby columns down with it. With the buckling of these critical columns, the collapse then progressed east-to-west across the core, ultimately overloading the perimeter support, which buckled between Floors 7 and 17, causing the remaining portion of the building above to fall down as a single unit. The fires, which were fueled by office contents and burned for 7 hours, along with the lack of water, were the key reasons for the collapse.[6]: 21–22 At the time, this made the old 7 WTC the only steel skyscraper to have collapsed from fire.[8]

When 7 WTC collapsed, debris caused substantial damage and contamination to the Borough of Manhattan Community College's Fiterman Hall building, located adjacent at 30 West Broadway, to the extent that the building was not salvageable.[47] A revised plan called for demolition in 2009 and completion of the new Fiterman Hall in 2012, at a cost of $325 million.[48] The Verizon Building, an art deco building located directly to the west, had extensive damage to its eastern facade from the collapse of 7 World Trade Center, though it was later restored at a cost of US$1.4 billion.[49]

Files relating to numerous federal investigations had been housed in 7 World Trade Center. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission estimated over 10,000 of its cases were affected.[50] Investigative files in the Secret Service's largest field office were lost, with one Secret Service agent saying, "All the evidence that we stored at 7 World Trade, in all our cases, went down with the building."[51] Copies of emails in connection with the WorldCom scandal that were later requested by the SEC from Salomon Brothers, a subsidiary of Citigroup housed in the building, were also destroyed.[52]

The NIST report found no evidence supporting the conspiracy theories that 7 World Trade Center was brought down by controlled demolition. Specifically, the window breakage pattern and blast sounds that would have resulted from the use of explosives were not observed.[6]: 26–28 The suggestion that an incendiary material such as thermite was used instead of explosives was considered unlikely by NIST because of the building's structural response to the fire, the nature of the fire, and the unlikelihood that a sufficient amount of thermite could be planted without discovery.[7] Based on its investigation, NIST reiterated several recommendations it had made in its earlier report on the collapse of the Twin Towers.[6]: 63–73 It urged immediate action on a further recommendation: that fire resistance should be evaluated under the assumption that sprinklers are unavailable;[6]: 65–66 and that the effects of thermal expansion on floor support systems be considered.[6]: 65, 69 Recognizing that current building codes are drawn to prevent loss of life rather than building collapse, the main point of NIST's recommendations was that buildings should not collapse from fire even if sprinklers are unavailable.[6]: 63–73

New building

| Rebuilding of the World Trade Center |

|---|

| One WTC |

|

| 2–7 WTC |

| Other elements |

|

Liberty Park

Performing Arts Center

Vehicular Security Center

Westfield World Trade Center

St. Nicholas Greek Orthodox Church |

The new 7 World Trade Center has 52 stories and is 741 ft (226 m) tall.[53] The building has 42 floors of leasable space, starting at the 11th floor, and a total of 1.7 million sq ft (160,000 m2) of office space.[54] The first ten floors house an electrical substation which provides power to much of Lower Manhattan. The office tower has a narrower footprint at ground level than did its predecessor, so the course of Greenwich Street could be restored to reunite TriBeCa and the Financial District. The original building, on the other hand, had bordered West Broadway on the east, necessitating the destruction of Greenwich Street between Barclay Street and the northern border of the World Trade Center superblock.[55]

Design

David Childs of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill worked in conjunction with glass artist and designer James Carpenter to create a design that uses ultra-clear, low-iron glass to provide reflectivity and light, with stainless-steel spandrels behind the glass to help reflect sunlight.[56] Stainless steel used in the building façade is molybdenum-containing Type 316, which provides improved resistance to corrosion.[57] To enclose the power substation and improve its aesthetics, the base of the building has a curtain wall with stainless steel louvers that provide ventilation for the machinery.[58] During the day, the curtain wall reflects light, while at night it is illuminated with blue LED lights.[59] The curtain wall around the lobby uses heavily laminated, heat-strengthened glass that meets high standards for blast resistance.[60] At night, a large cube of light above the lobby also emanates blue light, while during the day it provides white light to the lobby, and at dusk, it transitions to violet and back to blue.[61] Inside the main lobby, artist Jenny Holzer created a large light installation with glowing text moving across wide plastic panels.[56] The entire wall, which is 65 ft (20 m) wide and 14 ft (4.3 m) tall, changes color according to the time of day. Holzer worked with Klara Silverstein, the wife of Larry Silverstein, to select poetry for the art installation. The wall is structurally fortified as a security measure.[62]

The building is being promoted as the safest skyscraper in the U.S.[63] According to Silverstein Properties, the owner of the building, it "incorporate[s] a host of life-safety enhancements that will become the prototype for new high-rise construction."[64] The building has 2-foot-thick (0.61 m) reinforced-concrete and fireproofed elevator and stairway access shafts. The original building used only drywall to line these shafts.[65] The stairways are wider than in the original building to permit faster egress.[65]

7 World Trade Center is equipped with Otis destination elevators.[66] After pressing a destination floor number on a lobby keypad, passengers are grouped and directed to specific elevators that will stop at the selected floor (there are no buttons to press inside the elevators). This system is designed to reduce elevator waiting and travel times. The elevator system is integrated with the lobby turnstile and card reader system that identifies the floor on which a person works as he or she enters and can automatically call the elevator for that floor.[67]

Nearly 30 percent of structural steel used in the building consists of recycled steel.[68] Rainwater is collected and used for irrigation of the park and to cool the building.[56] Along with other sustainable design features, the building is designed to allow in plenty of natural light, power is metered to tenants to encourage them to conserve energy, the heating steam is reused to generate some power for the building, and recycled materials are used for insulation and interior materials.[69]

Construction

The construction phase of the new 7 World Trade Center began on May 7, 2002, with the installation of a fence around the construction site.[1] Tishman Construction Corporation of New York began work at the new 7 World Trade Center in 2002, soon after the site was cleared of debris. Restoring the Con Ed electrical substation was an urgent priority to meet power demands of Lower Manhattan.[55] Because 7 World Trade Center is separate from the main 16-acre (6.5 ha) World Trade Center site, Larry Silverstein required approval from only the Port Authority, and rebuilding was able to proceed quickly.[70]

Once construction of the power substation was completed in October 2003, work proceeded on building the office tower. An unusual approach was used in constructing the building; erecting the steel frame before adding the concrete core. This approach allowed the construction schedule to be shortened by a few months.[71] Construction was completed in 2006 at a cost of $700 million.[56] Though Silverstein received $861 million from insurance on the old building, he owed more than $400 million on its mortgage.[72] Costs to rebuild were covered by $475 million in Liberty Bonds, which provide tax-exempt financing to help stimulate rebuilding in Lower Manhattan and insurance money that remained after other expenses.[73]

A 15,000 sq ft (1,400 m2) triangular park was created between the extended Greenwich Street and West Broadway by David Childs with Ken Smith and his colleague, Annie Weinmayr, of Ken Smith Landscape Architect. The park comprises an open central plaza with a fountain and flanking groves of sweetgum trees and boxwood shrubs.[74] At the center of the fountain, sculptor Jeff Koons created Balloon Flower (Red), whose mirror-polished stainless steel represents a twisted balloon in the shape of a flower.[75]

2000s

The building was officially opened at noon on May 23, 2006, with a free concert featuring Suzanne Vega, Citizen Cope, Bill Ware Vibes, Brazilian Girls, Ollabelle, Pharaoh's Daughter, Ronan Tynan (of the Irish Tenors), and special guest Lou Reed.[76][77] Prior to opening, in March 2006, the new 7 World Trade Center frontage and lobby were used in scenes for the movie Perfect Stranger with Halle Berry and Bruce Willis.[78]

After the building opened, several unleased upper floors were used for events such as charity lunches, fashion shows, and black-tie galas. Silverstein Properties allowed space in the new building to be used for these events as a means to draw people to see the building.[79] From September 8 to October 7, 2006, the work of photographer Jonathan Hyman was displayed in "An American Landscape", a free exhibit hosted by the World Trade Center Memorial Foundation at 7 World Trade Center. The photographs captured the response of people in New York City and across the United States after the September 11, 2001, attacks. The exhibit took place on the 45th floor while space remained available for lease.[80]

By March 2007, 60 percent of the building had been leased.[81] In September 2006, Moody's signed a 20-year lease to rent 15 floors of 7 World Trade Center.[82] Other tenants that had signed leases in 7 World Trade Center, as of May 2007, included ABN AMRO,[83] Ameriprise Financial Inc.,[84][77] law firm Wilmer Hale,[85] publisher Mansueto Ventures,[86] and the New York Academy of Sciences.[87][77] Silverstein Properties also has offices and the Silver Suites executive office suites[88] in 7 World Trade Center, along with office space used by the architectural and engineering firms working on 1 World Trade Center, 150 Greenwich Street, 175 Greenwich Street, and 200 Greenwich Street.[89] After AMN AMRO was acquired by the Royal Bank of Scotland, forex services provider FXDD subleased some of the Royal Bank of Scotland's space in 2009.[90]

The space occupied by Mansueto Ventures has been designed to use the maximum amount of natural light and has an open floor plan.[91] The space used by the New York Academy of Sciences on the 40th floor, designed by H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture, works with the parallelogram shape of the building. Keeping with the green design of the building, the NYAS uses recycled materials in many of the office furnishings, has zoned heating and cooling, and motion-detecting lights, which activate automatically when people are present, and adjust according to incoming sunlight.[92]

2010s to present

The building became fully leased in September 2011 after MSCI agreed to occupy 125,000 square feet (11,600 m2) on the top floor.[93][94] Following this, Silverstein announced in 2012 that he would refinance the building with a $452.8 million Liberty bond issue and a $125 million commercial mortgage-backed security loan.[95][96] At the time, the building was valued at $940 million, in large part because it was fully occupied.[96] FXDD subleased its space to engineering company Permasteelisa in 2015[97] and artificial intelligence firm IPsoft in 2016.[98] The building was 94.8 percent occupied by 2017. At the time, roughly three-quarters of the space was occupied by four tenants, including Moody's, the Royal Bank of Scotland, and Wilmer Hale.[99]

Wedding planning company Zola[100] and the building's own architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill both leased space at 7 WTC in early 2019.[101] This was followed in July 2019 by luxury drink brand Moët Hennessy[102][103] and media company AccuWeather.[103] After publisher Mansueto Ventures and three other firms took space at 7 WTC in April 2022, the building was 97 percent occupied.[104][105] Shortly afterward, Silverstein Properties refinanced the property with a $458 million loan from Goldman Sachs.[105][106][107]

See also

- List of tallest buildings in New York City

- World Trade Center in popular culture

References

- Bagli, Charles V. (May 8, 2002). "As a Hurdle Is Cleared, Building Begins At Ground Zero". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2009.

- "7 World Trade Center – The Skyscraper Center". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Archived from the original on April 20, 2013.

- 7 World Trade Center Archived December 11, 2013, at the Wayback Machine, Skidmore, Owings & Merrill

- See: * Building Tenants Archived February 5, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, Silverstein Properties *

- Gilsanz, Ramon; Edward M. DePaola; Christopher Marrion; Harold "Bud" Nelson (May 2002). "WTC7 (Chapter 5)" (PDF). World Trade Center Building Performance Study. FEMA. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 5, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "NIST NCSTAR1-A: Final Report on the Collapse of World Trade Center Building 7". Final Reports of the Federal Building and Fire Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology. November 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- "Questions and Answers about the NIST WTC 7 Investigation". Nist. National Institute of Standards and Technology. May 24, 2010. Archived from the original on August 27, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Rudin, Mike (July 4, 2008). "9/11 third tower mystery 'solved'". BBC News. Archived from the original on September 3, 2014. Retrieved September 11, 2014.

- "About the WTC". Wtc.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2011. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- Lew, H.S.; Bukowski, Richard W.; Nicholas J. Carino (September 2005). Design, Construction, and Maintenance of Structural and Life Safety Systems (NCSTAR 1-1). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 13.

- "Seven World Trade Center (pre-9/11)". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2006. Retrieved May 7, 2006.

- Berger, Joseph (October 1, 1984). "Work Set on Last Trade Center Unit". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 1, 2018. Retrieved March 1, 2018.

- "History of the World Trade Center". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on June 7, 2015. Retrieved May 26, 2015.

- McAllister, T. P.; Gann, R. G.; Averill, J. D.; Gross, J. L.; Grosshandler, W. L.; Lawson, J. R.; McGrattan, K. B.; Pitts, W. M.; Prasad, K. R.; Sadek, F. H.; Nelson, H. E. (August 2008). "NIST NCSTAR 1–9: Structural Fire Response and Probable Collapse Sequence of World Trade Center Building 7". Final Reports of the Federal Building and Fire Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology. pp. 9–45. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- Salvarinas, John J. (1986). Seven World Trade Center, New York, Fabrication and Construction Aspects. Proceedings of the 1986 Canadian Structural Engineering Conference. Vancouver: Canadian Steel Construction Council.

- Lew, H.S. (September 2005). "NIST NCSTAR 1-1: Design, Construction, and Maintenance of Structural and Life Safety Systems" (PDF). Final Reports of the Federal Building and Fire Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology. pp. xxxvii. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Milke, James (Spring 2003). "Study of Building Performance in the WTC Disaster". Fire Protection Engineering. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Grill, Raymond A.; Johnson, Duane A. (September 2005). "NIST NCSTAR 1-1J: Documentation of the Fuel System for Emergency Power in World Trade Center 7" (PDF). Final Reports of the Federal Building and Fire Investigation of the World Trade Center Disaster. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 30, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- See:

Glanz, James; Lipton, Eric (December 20, 2001). "City Had Been Warned of Fuel Tank at 7 World Trade Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 28, 2007. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

Barrett, Wayne (July 31, 2007). "Rudy Giuliani's 5 Big Lies About 9/11". Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 3, 2017. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

"Transcript: Rudy Giuliani on 'FNS'". Fox News. May 14, 2007. Archived from the original on October 10, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2007.Then why did he say the building – he said it's not – the place in Brooklyn is not as visible a target as buildings in Lower Manhattan

Buettner, Russ (May 22, 2007). "Onetime Giuliani Insider Is Now a Critic". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved June 12, 2007.

"Giuliani Blames Aide for Poor Emergency Planning". New York Magazine. May 15, 2007. Archived from the original on May 17, 2007. Retrieved June 12, 2007. - National Construction Safety Team Advisory Committee. "Meeting of the National Construction Safety Team Advisory Committee, December 18, 2007" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on February 12, 2017.

- Horsley, Carter B (October 25, 1981). "Lower Manhattan Luring Office Developers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- See:

"Al Held". National Gallery of Australia. Archived from the original on June 9, 2007. Retrieved May 29, 2007.

Plagens, Peter (April 17, 1989). "Is Bigger Necessarily Better?". Newsweek. - Scardino, Albert (July 11, 1986). "A Realty Gambler's Big Coup". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 30, 2021. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Scardino, Albert (December 3, 1986). "$3 Billion Office Pact Canceled by Drexel". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Berg, Eric N (April 7, 1988). "Talking Deals; Developer Plays A Waiting Game". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Berkowitz, Harry (November 29, 1988). "Salomon to Move Downtown". Newsday.

- McCain, Mark (February 19, 1989). "The Salomon Solution; A Building Within a Building, at a Cost of $200 Million". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 19, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- "Building: 7 World Trade Center". CNN. 2001. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- Glanz, James; Eric Lipton (November 16, 2001). "Workers Shore Up Wall Keeping Hudson's Waters Out". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on September 17, 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- "CIA Lost Office In WTC: A secret office operated by the CIA was destroyed in the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center, seriously disrupting intelligence operations'". CBSNews.com / AP. November 5, 2001. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "Interim Report on WTC 7" (PDF). Appendix L. National Institute of Standards and Technology. 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2007. Retrieved August 20, 2007.

- Grosshandler, William. "Active Fire Protection Systems Issues" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved September 11, 2007.

- Evans, David D (September 2005). "Active Fire Protection Systems" (PDF). Nist. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 31, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- "Oral Histories From Sept. 11 – Interview with Captain Anthony Varriale" (PDF). The New York Times. December 12, 2001. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 2, 2007. Retrieved August 22, 2007.

-

- Spak, Steve (September 11, 2001). WTC 9-11-01 Day of Disaster (Video). New York City: Steve Spak. Archived from the original on October 27, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

Scheuerman, Arthur (December 8, 2006). The Collapse of Building 7 (PDF) (Report). National Institute of Standards and Technology. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 3, 2007. Retrieved June 29, 2007.

- Spak, Steve (September 11, 2001). WTC 9-11-01 Day of Disaster (Video). New York City: Steve Spak. Archived from the original on October 27, 2018. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- "WTC: This Is Their Story, Interview with Chief Peter Hayden". Firehouse.com. September 9, 2002. Archived from the original on March 6, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- "WTC: This Is Their Story, Interview with Captain Chris Boyle". Firehouse.com. August 2002. Archived from the original on April 10, 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2011.

- "Oral Histories From Sept. 11 – Interview with Chief Daniel Nigro". The New York Times. October 24, 2001. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 4, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- Lipton, Eric (August 21, 2008). "Fire, Not Explosives, Felled 3rd Tower on 9/11, Report Says". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 9, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- CBS News (September 11, 2001). CBS Sept. 11, 2001 4:51 pm – 5:33 pm (September 11, 2001) (Television). WUSA, CBS 9, Washington, D.C. – View footage on YouTube of the collapse captured by CBS.

- "Debunking the 9/11 Myths: Special Report – The World Trade Center". Popular Mechanics. April 7, 2010. Archived from the original on March 20, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- See:

"World Trade Center Investigation Team Members". Nist. National Institute of Standards and Technology. July 27, 2011. Archived from the original on January 11, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2011.

"Commerce's NIST Details Federal Investigation of World Trade Center Collapse". Nist. National Institute of Standards and Technology. August 2002. Archived from the original on November 27, 2011. Retrieved November 21, 2011. - "Answers to Frequently Asked Questions". National Institute of Standards and Technology. August 2006. Archived from the original on February 14, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Newman, Michael (June 29, 2007). "NIST Status Update on World Trade Center 7 Investigation" (Press release). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original on August 29, 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- McAllister, Therese; et al. (January 2012). "Analysis of Structural Response of WTC 7 to Fire and Sequential Failures Leading to Collapse". Journal of Structural Engineering. 138 (1): 109–117. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0000398.

- McAllister, Therese (December 12, 2006). "WTC 7 Technical Approach and Status Summary" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 5, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "Fiterman Hall — Project Updates". Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center/LMDC. Archived from the original on September 12, 2007. Retrieved August 23, 2007.

- See:

"Fiterman is Funded". BMCC News. November 17, 2008. Archived from the original on December 28, 2008.

Agovino T (November 13, 2008). "Ground Zero building to be razed". Crain's New York Business. Archived from the original on October 3, 2009. Retrieved May 5, 2022. - "Verizon Building Restoration". New York Construction (McGraw Hill). Archived from the original on September 26, 2007. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- "Federal Agencies: Re-Creating Lost Files". New York Lawyer. September 14, 2001. Archived from the original on April 8, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- "Ground Zero for the Secret Service". July 23, 2002. Archived from the original on July 1, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- "Citigroup Facing Subpoena in IPO Probe". The Street. Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- See:

"7 World Trade Center". World Trade Center. Archived from the original on December 30, 2009. Retrieved January 9, 2010.

Ramirez, Anthony (September 30, 2004). "Construction Worker Dies in Fall at Trade Center Site". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 5, 2022. Retrieved May 20, 2008. - "Seven World Trade Center (post-9/11)". Emporis.com. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved November 22, 2007.

- Dunlap, David W (April 11, 2002). "21st-Century Plans, but Along 18th-Century Paths". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "Major Step at Ground Zero: 7 World Trade Center Opening". Architectural Record. May 17, 2006. Archived from the original on May 22, 2006. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Houska, Catherine (January 2004). "New 7 World Trade Center Uses Type 316 Stainless Steel". International Molybdenum Association News Letter: 4–6.

- Blum, Andrew (March 28, 2006). "A World of Light and Glass". BusinessWeek. Archived from the original on March 24, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Marpillero, Sandro; Frampton, Kenneth; Schlaich, Jorg (2006). James Carpenter: Environmental Refractions. Princeton Architectural Press. pp. 55–70. ISBN 1-56898-608-4.

- Garmhausen, Steve (November 16, 2004). "Curtain (Wall) Time". Slatin Report. Archived from the original on February 25, 2005. Retrieved February 25, 2005.

- "7 World Trade Center — Outstanding Achievement, Exterior Lighting". Architectural Lighting Magazine. July 1, 2007. Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Collins, Glenn (March 6, 2006). "At Ground Zero, Accord Brings a Work of Art". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- "Downtown Construction and Building Information". Lower Manhattan Construction Command Center. Archived from the original on May 17, 2006. Retrieved May 22, 2006.

- "Silverstein Properties Names CB Richard Ellis to Serve as Exclusive Leasing Agent for 7 World Trade Center" (Press release). Silverstein Properties. September 28, 2004.

- Reiss, Matthew (March 2003). "Shortcuts to Safety". Metropolis Magazine / Skyscraper Safety Campaign. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Angwin, Julia (November 19, 2006). "No-button elevators take orders in lobby". Charleston Gazette (West Virginia).

- Kretkowski, Paul (March 2007). "First Up". ARCHI-TECH. Archived from the original on October 13, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Pogrebin, Robin (April 16, 2006). "7 World Trade Center and Hearst Building: New York's Test Cases for Environmentally Aware Office Towers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 11, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- DePalma, Anthony (January 20, 2004). "At Ground Zero, Rebuilding With Nature in Mind". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 26, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Bagli, Charles V (January 31, 2002). "Developer's Pace at 7 World Trade Center Upsets Some". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 25, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Post, Nadine M (September 12, 2005). "Strategy for Seven World Trade Center Exceeds Expectations". Engineering News Record. Archived from the original on December 10, 2005. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Herman, Eric (May 31, 2002). "No Tenants for New 7 WTC, Construction to Begin with Financing in Doubt". Daily News (New York).

- Pristin, Terry (July 12, 2006). "A Pot of Tax-Free Bonds for Post-9/11 Projects Is Empty". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 23, 2009. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Collins, Glenn (July–August 2006). "A Prism with Prose — Seven World Trade Center". Update Unbound. New York Academy of Science. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Dunlap, David W (May 24, 2006). "Luster of 7 World Trade Center Has Tattered Reminder of 9/11". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- "7 World Trade Center Opens with Musical Fanfare". Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC). May 22, 2006. Archived from the original on August 9, 2007. Retrieved July 27, 2007.

- WESTFELDT, AMY (May 23, 2006). "First Rebuilt Skyscraper at WTC Opens". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- "Under Cover, Tower 7 is no 'Stranger' to fame". Downtown Express. March 2006. Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Birkner, Gabrielle (May 14, 2007). "The City's Hottest Event Space? Try 7 World Trade Center". New York Sun. Archived from the original on March 30, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "WTC Memorial Foundation Announces Photography Exhibitions to Mark 5th Anniversary of 9/11" (PDF) (Press release). World Trade Center Memorial Foundation. August 7, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Spitz, Rebecca (August 31, 2006). "9/11: Five Years Later: 7 World Trade Open For Business, Lacking Tenants". NY1 News. Archived from the original on February 15, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- See:

"Moody's signs on dotted line at 7WTC". Real Estate Weekly. September 20, 2006. Archived from the original on January 20, 2022. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

"Pricey Midtown Rents Mean Big Tenant for 7 WTC". Gothamist. June 20, 2006. Archived from the original on February 21, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008. - Pristin, Terry (February 28, 2007). "Lower Manhattan: A Relative Bargain but Filling Up Fast". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- "Ameriprise Financial to lease 20,000 SF at 7 WTC" (Press release). AmeriPrise Financial. January 4, 2006. Archived from the original on October 27, 2014. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- "Darby & Darby P.C. to move headquarters to 7 WTC" (Press release). Darby & Darby. August 24, 2006. Archived from the original on November 6, 2006.

- "Mansueto Ventures signs lease at 7 World Trade Center to become the first corporate tenant to locate its national headquarters in the building" (Press release). Goliath. July 26, 2006. Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- "New York Academy of Sciences Signs Lease at 7 WTC". New York Academy of Sciences. December 16, 2005. Archived from the original on February 25, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- Levere, Jane (January 29, 2013). "Seeing Big Promise in Manhattan Corporate Apartments". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 4, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- See:

Dunlap, David W (January 25, 2007). "What a View to Behold, And It's Really Something". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017.

Dunlap, David W (January 18, 2007). "Behind the Scenes, Three Towers Take Shape". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 22, 2017. Retrieved February 4, 2017. - Geminder, Emily (November 30, 2009). "Midtown, Schmidtown! Currency Trader FXDD Subleases 40K Feet in 7 WTC". Observer. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Wilson, Claire (May 13, 2007). "An Open, Sunlit Space At 7 World Trade Center". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 10, 2008. Retrieved February 17, 2008.

- H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture (2007). The New York Academy of Sciences (brochure). H3 Hardy Collaboration Architecture.

- Chaban, Matt (September 19, 2011). "Zero Ground: 7 World Trade Center Now Fully Leased". Observer. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- "7 World Trade Center Skyscraper Fully Leased". NBC New York. September 19, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2022.

- Hlavenka, Jacqueline (March 19, 2012). "Silverstein To Refinance $577M in Bonds at 7 WTC". GlobeSt. Archived from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Brown, Eliot (March 19, 2012). "For Silverstein, Time to Celebrate". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Santani, Hitem (March 4, 2015). "A firm key to the rebuilding of 7WTC will now call it home". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Cullen, Terence (June 9, 2016). "Artificial Intelligence Company IPsoft Takes 27K SF at 7 WTC". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Gourarie, Chava (December 1, 2017). "Fitch upgrades CMBS debt on 7 WTC". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Kim, Betsy (January 17, 2019). "Zola Gets Hitched to 7 WTC". GlobeSt. Archived from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Baird-Remba, Rebecca (May 6, 2019). "Architecture Firm SOM Nails Down 80K SF at 7 WTC". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Rizzi, Nicholas (July 2, 2019). "Moët Hennessy Ditching Chelsea for 7 WTC". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- "Itʼs raining deals at 7 World Trade Center". Real Estate Weekly. July 11, 2019. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Young, Celia (April 7, 2022). "Publisher, Investment Manager Each Take 40K SF at 7 WTC". Commercial Observer. Archived from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- "Silverstein Properties signs four leases at 7 World Trade Center". Real Estate Weekly. April 9, 2022. Archived from the original on July 28, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- "Silverstein Scores $458M Refinancing at 7 World Trade Center". The Real Deal New York. April 7, 2022. Archived from the original on May 18, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

- Morphy, Erika (April 7, 2022). "7 World Trade Center Lands 104k-SF in Leases; Secures $457.5M Refi". GlobeSt. Archived from the original on July 29, 2022. Retrieved July 28, 2022.

External links

- 7 World Trade Center at SilversteinProperties.com

- 7 World Trade Center on CTBUH Skyscraper Center