Social group

In the social sciences, a social group can be defined as two or more people who interact with one another, share similar characteristics, and collectively have a sense of unity.[1] Regardless, social groups come in a myriad of sizes and varieties. For example, a society can be viewed as a large social group. The system of behaviors and psychological processes occurring within a social group or between social groups is known as group dynamics.

| Part of a series on |

| Sociology |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

|

|

Definition

Social cohesion approach

A social group exhibits some degree of social cohesion and is more than a simple collection or aggregate of individuals, such as people waiting at a bus stop, or people waiting in a line. Characteristics shared by members of a group may include interests, values, representations, ethnic or social background, and kinship ties. Kinship ties being a social bond based on common ancestry, marriage or adoption.[2] In a similar vein, some researchers consider the defining characteristic of a group as social interaction.[3] According to Dunbar's number, on average, people cannot maintain stable social relationships with more than 150 individuals.[4]

Social psychologist Muzafer Sherif proposed to define a social unit as a number of individuals interacting with each other with respect to:[5]

- Common motives and goals

- An accepted division of labor, i.e. roles

- Established status (social rank, dominance) relationships

- Accepted norms and values with reference to matters relevant to the group

- Development of accepted sanctions (praise and punishment) if and when norms were respected or violated

This definition is long and complex, but it is also precise. It succeeds in providing the researcher with the tools required to answer three important questions:

- "How is a group formed?"

- "How does a group function?"

- "How does one describe those social interactions that occur on the way to forming a group?"

Significance of that definition

The attention of those who use, participate in, or study groups has focused on functioning groups, on larger organizations, or on the decisions made in these organizations.[6] Much less attention has been paid to the more ubiquitous and universal social behaviors that do not clearly demonstrate one or more of the five necessary elements described by Sherif.

Some of the earliest efforts to understand these social units have been the extensive descriptions of urban street gangs in the 1920s and 1930s, continuing through the 1950s, which understood them to be largely reactions to the established authority.[7] The primary goal of gang members was to defend gang territory, and to define and maintain the dominance structure within the gang. There remains in the popular media and urban law enforcement agencies an avid interest in gangs, reflected in daily headlines which emphasize the criminal aspects of gang behavior. However, these studies and the continued interest have not improved the capacity to influence gang behavior or to reduce gang related violence.

The relevant literature on animal social behaviors, such as work on territory and dominance, has been available since the 1950s. Also, they have been largely neglected by policy makers, sociologists and anthropologists. Indeed, vast literature on organization, property, law enforcement, ownership, religion, warfare, values, conflict resolution, authority, rights, and families have grown and evolved without any reference to any analogous social behaviors in animals. This disconnect may be the result of the belief that social behavior in humankind is radically different from the social behavior in animals because of the human capacity for language use and rationality. Of course, while this is true, it is equally likely that the study of the social (group) behaviors of other animals might shed light on the evolutionary roots of social behavior in people.

Territorial and dominance behaviors in humans are so universal and commonplace that they are simply taken for granted (though sometimes admired, as in home ownership, or deplored, as in violence). But these social behaviors and interactions between human individuals play a special role in the study of groups: they are necessarily prior to the formation of groups. The psychological internalization of territorial and dominance experiences in conscious and unconscious memory are established through the formation of social identity, personal identity, body concept, or self concept. An adequately functioning individual identity is necessary before an individual can function in a division of labor (role), and hence, within a cohesive group. Coming to understand territorial and dominance behaviors may thus help to clarify the development, functioning, and productivity of groups.

Social identification approach

Explicitly contrasted against a social cohesion based definition for social groups is the social identity perspective, which draws on insights made in social identity theory.[8] Here, rather than defining a social group based on expressions of cohesive social relationships between individuals, the social identity model assumes that "psychological group membership has primarily a perceptual or cognitive basis."[9] It posits that the necessary and sufficient condition for individuals to act as group members is "awareness of a common category membership" and that a social group can be "usefully conceptualized as a number of individuals who have internalized the same social category membership as a component of their self concept."[9] Stated otherwise, while the social cohesion approach expects group members to ask "who am I attracted to?", the social identity perspective expects group members to simply ask "who am I?"

Empirical support for the social identity perspective on groups was initially drawn from work using the minimal group paradigm. For example, it has been shown that the mere act of allocating individuals to explicitly random categories is sufficient to lead individuals to act in an ingroup favouring fashion (even where no individual self-interest is possible).[10] Also problematic for the social cohesion account is recent research showing that seemingly meaningless categorization can be an antecedent of perceptions of interdependence with fellow category members.[11]

While the roots of this approach to social groups had its foundations in social identity theory, more concerted exploration of these ideas occurred later in the form of self-categorization theory.[12] Whereas social identity theory was directed initially at the explanation of intergroup conflict in the absence of any conflict of interests, self-categorization theory was developed to explain how individuals come to perceive themselves as members of a group in the first place, and how this self-grouping process underlies and determines all problems subsequent aspects of group behaviour.[13]

Defining characteristics

In his text, Group Dynamics, Forsyth (2010) discuses several common characteristics of groups that can help to define them.[14]

1) Interaction

This group component varies greatly, including verbal or non-verbal communication, social loafing, networking, forming bonds, etc. Research by Bales (cite, 1950, 1999) determine that there are two main types of interactions; relationship interactions and task interactions.

- Relationship interactions: “actions performed by group members that relate to or influence the emotional and interpersonal bonds within the group, including both positive actions (social support, consideration) and negative actions (criticism, conflict).”[14]

- Task interactions: “actions performed by group members that pertain to the group’s projects, tasks, and goals.”[14] This involve members organizing themselves and utilizing their skills and resources to achieve something.

2) Goals

Most groups have a reason for their existence, be it increasing the education and knowledge, receiving emotional support, or experiencing spirituality or religion. Groups can facilitate the achievement of these goals.[14] The circumplex model of group tasks by Joseph McGrath[15] organizes group related tasks and goals. Groups may focus on several of these goals, or one area at a time. The model divides group goals into four main types, which are further sub-categorized

- Generating: coming up with ideas and plans to reach goals

- Planning Tasks

- Creativity Tasks

- Choosing: Selecting a solution.

- Intellective Tasks

- Decision-making Tasks

- Negotiating: Arranging a solution to a problem.

- Cognitive Conflict Tasks

- Mixed Motive Task

- Executing: Act of carrying out a task.

- Contests/Battles/Competitive Tasks

- Performance/Psychomotor Tasks

3) Interdependence in relation

“The state of being dependent, to some degree, on other people, as when one’s outcomes, actions, thoughts, feelings, and experiences are determined in whole or part by others."[14] Some groups are more interdependent than others. For example, a sports team would have a relatively high level of interdependence as compared to a group of people watching a movie at the movie theater. Also, interdependence may be mutual (flowing back and forth between members) or more linear/unilateral. For example, some group members may be more dependent on their boss than the boss is on each of the individuals.

4) Structure

Group structure involves the emergence or regularities, norms, roles and relations that form within a group over time. Roles involve the expected performance and conduct of people within the group depending on their status or position within the group. Norms are the ideas adopted by the group pertaining to acceptable and unacceptable conduct by members. Group structure is a very important part of a group. If people fail to meet their expectations within to groups, and fulfil their roles, they may not accept the group, or be accepted by other group members.

5) Unity

When viewed holistically, a group is greater than the sum of its individual parts. When people speak of groups, they speak of the group as a whole, or an entity, rather than speaking of it in terms of individuals. For example, it would be said that “The band played beautifully.” Several factors play a part in this image of unity, including group cohesiveness, and entitativity (appearance of cohesion by outsiders).[14]

Types

There are four main types of groups: 1) primary groups, 2) social groups, 3) collectives, and 4) categories.[16]

1) Primary groups

Primary groups[16] are small, long-term groups characterized by high amounts of cohesiveness, member identification, face-to-face interaction, and solidarity. Such groups may act as the principal source of socialization for individuals as primary groups may shape an individual's attitudes, values, and social orientation.

Three sub-groups of primary groups are:[17]

- kin (relatives)

- close friends

- neighbours.

2) Social groups

Social groups[16] are also small groups but are of moderate duration. These groups are often formed due to a common goal. In this type of group, it is possible for outgroup members (i.e., social categories of which one is not a member)[18] to become ingroup members (i.e., social categories of which one is a member)[18] with reasonable ease. Social groups, such as study groups or coworkers, interact moderately over a prolonged period of time.

3) Collectives

In contrast, spontaneous collectives,[16] such as bystanders or audiences of various sizes, exist only for a very brief period of time and it is very easy to become an ingroup member from an outgroup member and vice versa. Collectives may display similar actions and outlooks.

4) Categories

Categories[16] consist of individuals that are similar to one another in a certain way, and members of this group can be permanent ingroup members or temporary ingroup members. Examples of categories are individuals with the same ethnicity, gender, religion, or nationality. This group is generally the largest type of group.

Health

The social groups people are involved with in the workplace directly affect their health. No matter where you work or what the occupation is, feeling a sense of belonging in a peer group is a key to overall success.[19] Part of this is the responsibility of the leader (manager, supervisor, etc.). If the leader helps everyone feel a sense of belonging within the group, it can help boost morale and productivity. According to Dr. Niklas Steffens "Social identification contributes to both psychological and physiological health, but the health benefits are stronger for psychological health".[20] The social relationships people have can be linked to different health conditions. Lower quantity or quality social relationships have been connected to issues such as: development of cardiovascular disease, recurrent myocardial infarction, atherosclerosis, autonomic dysregulation, high blood pressure, cancer and delayed cancer recovery, and slower wound healing as well as inflammatory biomarkers and impaired immune function, factors associated with adverse health outcomes and mortality. The social relationship of marriage is the most studied of all, the marital history over the course of one's life can form differing health outcomes such as cardiovascular disease, chronic conditions, mobility limitations, self-rated health, and depressive symptoms. Social connectedness also plays a large part in overcoming certain conditions such as drug, alcohol, or substance abuse. With these types of issues, a person's peer group play a big role in helping them stay sober. Conditions do not need to be life-threatening, one's social group can help deal with work anxiety as well. When people are more socially connected have access to more support.[21] Some of the health issues people have may also stem from their uncertainty about just where they stand among their colleagues. It has been shown that being well socially connected has a significant impact on a person as they age, according to a 10-year study by the MacArthur Foundation, which was published in the book 'Successful Aging'[22] the support, love, and care we feel through our social connections can help to counteract some of the health-related negatives of aging. Older people who were more active in social circles tended to be better off health-wise.[23]

Group membership and recruitment

Social groups tend to form based on certain principles of attraction, that draw individuals to affiliate with each other, eventually forming a group.

- The Proximity Principle – the tendency for individuals to develop relationships and form groups with those they are (often physically) close to. This is often referred to as ‘familiarity breeds liking’, or that we prefer things/people that we are familiar with [24]

- The Similarity Principle – the tendency for individuals to affiliate with or prefer individuals who share their attitudes, values, demographic characteristics, etc.

- The Complementarity Principle – the tendency for individuals to like other individuals who are dissimilar from themselves, but in a complementary manner. E.g. leaders will attract those who like being led, and those who like being led will attract leaders [25]

- The Reciprocity Principle – the tendency for liking to be mutual. For example, if A likes B, B is inclined to like A. Conversely, if A dislikes B, B will probably not like A (negative reciprocity)

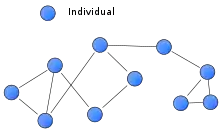

- The Elaboration Principle – the tendency for groups to complexify over time by adding new members through their relationships with existing group members. In more formal or structured groups, prospective members may need a reference from a current group member before they can join.

Other factors also influence the formation of a group. Extroverts may seek out groups more, as they find larger and more frequent interpersonal interactions stimulating and enjoyable (more than introverts). Similarly, groups may seek out extroverts more than introverts, perhaps because they find they connect with extroverts more readily.[26] Those higher in relationality (attentiveness to their relations with other people) are also likelier to seek out and prize group membership. Relationality has also been associated with extroversion and agreeableness.[27] Similarly, those with a high need for affiliation are more drawn to join groups, spend more time with groups and accept other group members more readily.[28]

Previous experiences with groups (good and bad) inform people's decisions to join prospective groups. Individuals will compare the rewards of the group (e.g. belonging,[29] emotional support,[30] informational support, instrumental support, spiritual support; see Uchino, 2004 for an overview) against potential costs (e.g. time, emotional energy). Those with negative or 'mixed' experiences with previous groups will likely be more deliberate in their assessment of potential groups to join, and with which groups they choose to join. (For more, see Minimax Principal, as part of Social Exchange Theory)

Once a group has begun to form, it can increase membership through a few ways. If the group is an open group,[31] where membership boundaries are relatively permeable, group members can enter and leave the group as they see fit (often via at least one of the aforementioned Principles of Attraction). A closed group [31] on the other hand, where membership boundaries are more rigid and closed, often engages in deliberate and/or explicit recruitment and socialization of new members.

If a group is highly cohesive, it will likely engage in processes that contribute to cohesion levels, especially when recruiting new members, who can add to a group's cohesion, or destabilize it. Classic examples of groups with high cohesion are fraternities, sororities, gangs, and cults, which are all noted for their recruitment process, especially their initiation or hazing. In all groups, formal and informal initiations add to a group's cohesion and strengthens the bond between the individual and group by demonstrating the exclusiveness of group membership as well as the recruit's dedication to the group.[14] Initiations tend to be more formal in more cohesive groups. Initiation is also important for recruitment because it can mitigate any cognitive dissonance in potential group members.[32]

In some instances, such as cults, recruitment can also be referred to as conversion. Kelman's Theory of Conversion[33] identifies 3 stages of conversion: compliance (individual will comply or accept group's views, but not necessarily agree with them), identification (member begins to mimic group's actions, values, characteristics, etc.) and internalization (group beliefs and demands become congruent with member's personal beliefs, goals and values). This outlines the process of how new members can become deeply connected to the group.

Development

If one brings a small collection of strangers together in a restricted space and environment, provides a common goal and maybe a few ground rules, then a highly probable course of events will follow. Interaction between individuals is the basic requirement. At first, individuals will differentially interact in sets of twos or threes while seeking to interact with those with whom they share something in common: i.e., interests, skills, and cultural background. Relationships will develop some stability in these small sets, in that individuals may temporarily change from one set to another, but will return to the same pairs or trios rather consistently and resist change. Particular twosomes and threesomes will stake out their special spots within the overall space.

Again depending on the common goal, eventually twosomes and threesomes will integrate into larger sets of six or eight, with corresponding revisions of territory, dominance-ranking, and further differentiation of roles. All of this seldom takes place without some conflict or disagreement: for example, fighting over the distribution of resources, the choices of means and different subgoals, the development of what are appropriate norms, rewards and punishments. Some of these conflicts will be territorial in nature: i.e., jealousy over roles, or locations, or favored relationships. But most will be involved with struggles for status, ranging from mild protests to serious verbal conflicts and even dangerous violence.

By analogy to animal behavior, sociologists may term these behaviors territorial behaviors and dominance behaviors. Depending on the pressure of the common goal and on the various skills of individuals, differentiations of leadership, dominance, or authority will develop. Once these relationships solidify, with their defined roles, norms, and sanctions, a productive group will have been established.[34][35][36]

Aggression is the mark of unsettled dominance order. Productive group cooperation requires that both dominance order and territorial arrangements (identity, self-concept) be settled with respect to the common goal and within the particular group. Some individuals may withdraw from interaction or be excluded from the developing group. Depending on the number of individuals in the original collection of strangers, and the number of "hangers-on" that are tolerated, one or more competing groups of ten or less may form, and the competition for territory and dominance will then also be manifested in the inter group transactions.

Dispersal and transformation

Two or more people in interacting situations will over time develop stable territorial relationships. As described above, these may or may not develop into groups. But stable groups can also break up in to several sets of territorial relationships. There are numerous reasons for stable groups to "malfunction" or to disperse, but essentially this is because of loss of compliance with one or more elements of the definition of group provided by Sherif. The two most common causes of a malfunctioning group are the addition of too many individuals, and the failure of the leader to enforce a common purpose, though malfunctions may occur due to a failure of any of the other elements (i.e., confusions status or of norms).

In a society, there is a need for more people to participate in cooperative endeavors than can be accommodated by a few separate groups. The military has been the best example as to how this is done in its hierarchical array of squads, platoons, companies, battalions, regiments, and divisions. Private companies, corporations, government agencies, clubs, and so on have all developed comparable (if less formal and standardized) systems when the number of members or employees exceeds the number that can be accommodated in an effective group. Not all larger social structures require the cohesion that may be found in the small group. Consider the neighborhood, the country club, or the megachurch, which are basically territorial organizations who support large social purposes. Any such large organizations may need only islands of cohesive leadership.

For a functioning group to attempt to add new members in a casual way is a certain prescription for failure, loss of efficiency, or disorganization. The number of functioning members in a group can be reasonably flexible between five and ten, and a long-standing cohesive group may be able to tolerate a few hangers on. The key concept is that the value and success of a group is obtained by each member maintaining a distinct, functioning identity in the minds of each of the members. The cognitive limit to this span of attention in individuals is often set at seven. Rapid shifting of attention can push the limit to about ten. After ten, subgroups will inevitably start to form with the attendant loss of purpose, dominance-order, and individuality, with confusion of roles and rules. The standard classroom with twenty to forty pupils and one teacher offers a rueful example of one supposed leader juggling a number of subgroups.

Weakening of the common purpose once a group is well established can be attributed to: adding new members; unsettled conflicts of identities (i.e., territorial problems in individuals); weakening of a settled dominance-order; and weakening or failure of the leader to tend to the group. The actual loss of a leader is frequently fatal to a group, unless there was lengthy preparation for the transition. The loss of the leader tends to dissolve all dominance relationships, as well as weakening dedication to common purpose, differentiation of roles, and maintenance of norms. The most common symptoms of a troubled group are loss of efficiency, diminished participation, or weakening of purpose, as well as an increase in verbal aggression. Often, if a strong common purpose is still present, a simple reorganization with a new leader and a few new members will be sufficient to re-establish the group, which is somewhat easier than forming an entirely new group. This is the most common factor.

See also

- Bureaucracy

- Club (organization)

- Corporate group

- Crowd

- Crowd psychology

- Globalization

- Group conflict

- Group dynamics

- Group emotion

- Group narcissism

- Institution

- Intergroup relations

- Loneliness

- Mob rule

- Public opinion

- Secret society

- Social class

- Social isolation

- Social network

- Social organization

- Social representation

- Sociology of sport

- Status group

- Types of social groups

References

- Reicher, S. D. (1982). "The determination of collective behaviour." Pp. 41–83 in H. Tajfel (ed.), Social identity and intergroup relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Macionis, John, and Linda Gerber (2010). Sociology 7th Canadian Ed. Toronto, Ontario: Pearson Canada Inc.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hare, A. P. (1962). Handbook of small group research. New York: Macmillan Publishers.

- Gladwell 2002, pp. 177–81.

- Sherif, Muzafer, and Carolyn W. Sherif, An Outline of Social Psychology (rev. ed.). New York: Harper & Brothers. pp. 143–80.

- Simon, Herbert A. 1976. Administrative Behavior (3rd ed.). New York. Free Press. pp. 123–53.

- Sherif, op. cit. p. 149.

- Tajfel, H., and J. C. Turner (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W.G. Austin & S. Worchel (eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations. pp. 33–47. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole

- Turner, J.C. (1982). Tajfel, H. (ed.). "Towards a cognitive redefinition of the social group". Social Identity and Intergroup Relations. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 15–40.

- Tajfel, H., Billig, M., Bundy, R.P. & Flament, C. (1971). "Social categorization and intergroup behaviour". European Journal of Social Psychology, 2, 149–78,

- Platow, M.J.; Grace, D.M.; Smithson, M.J. (2011). "Examining the Preconditions for Psychological Group Membership: Perceived Social Interdependence as the Outcome of Self-Categorization". Social Psychological and Personality Science. 3 (1).

- Turner, J.C.; Reynolds, K.H. (2001). Brown, R.; Gaertner, S.L. (eds.). "The Social Identity Perspective in Intergroup Relations: Theories, Themes, and Controversies". Blackwell Handbook of Social Psychology. 3 (1).

- Turner, J. C. (1987) Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self-Categorization Theory. Oxford: Blackwell. pp. 42–67.

- Forsyth, Donelson R. (2010). Group Dynamics (5 ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, Cengage Learning.

- McGrath, Joseph, E. (1984). Groups: Interaction and Performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. pp. 61–62.

- Forsyth, Donelson R. 2009. Group Dynamics (5th ed.). New York: Wadsworth. ISBN 9780495599524.

- Litwak, Eugene, and Ivan Szelenyi. 1969. "Primary Group Structures and Their Functions: Kin, Neighbors, and Friends." American Sociological Review 34(4):465–81. doi:10.2307/2091957. – via ResearchGate.

- Quattrone, G.A., Jones, E.E. (1980). "The perception of variability within in-groups and out-groups: Implications for the law of small numbers". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 38 (1): 142. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.38.1.141.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Health determined by social relationships at work". phys.org. Society for Personality and Social Psychology. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04.

- "Workplace leaders improve employee wellbeing". phys.org. University Of Queensland. Archived from the original on 2016-11-04.

- Debra Umberson; Karas Montez, Jennifer (2010). "Social Relationships and Health: A Flashpoint for Health Policy". Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 51 (Suppl): S54–S66. doi:10.1177/0022146510383501. PMC 3150158. PMID 20943583.

- Rowe, J.W.; Kahn, R.L. (1997). "Successful Aging". The Gerontologist. 37 (4): 433–40. doi:10.1093/geront/37.4.433. PMID 9279031.

- Staackmann, Mary. "Social Connections are a Key to Aging Well". Chicago Tribune. The Evanston Review. Archived from the original on 2016-11-30.

- Bornstein, Robert F. (1989). "Exposure and affect: Overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968, 1987". Psychological Bulletin. 106 (2): 265–289. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.106.2.265.

- Tracey, Terence, Ryan, Jennifer M., Jaschik-Herman, Bruce (2001). "Complementarity of interpersonal circumplex traits". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 27 (7): 786–797. doi:10.1177/0146167201277002. S2CID 144304609.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Gardner, William L., Reithel, Brian J., Cogliser, Claudia C., Walumbwa, Fred O., Foley, Richard T. (2012). "Matching personality and organizational culture effects of recruitment strategy and the five-factor model on subjective person-organization fit". Management Communication Quarterly. 24: 585–622. doi:10.1177/0893318912450663. S2CID 146744551.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Cross, S. E., Bacon, P. L., Morris, M. L. (2000). "The relational-interdependent self-construal and relationships". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 78 (4): 791–808. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.191. PMID 10794381.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McAdams, Dan P., Constantian, Carol A. (1983). "Intimacy and affiliation motives in daily living: An experience in sampling analysis". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 45 (4): 851–861. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.45.4.851.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kruase, Neal, Wulff, Keith M. (2005). "Church-based social ties, a sense of belonging in a congregation, and physical health status". International Journal for the Psychology of Religion. 15: 75–93.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McGuire, Gail M. (2007). "Intimate work: A typology of the social support that workers provide to their network members". Work and Occupations. 34: 125–147. doi:10.1177/0730888406297313. S2CID 145394891.

- Ziller, R. C. (1965). "Toward a theory of open and closed groups". Psychological Bulletin. 34 (3): 164–182. doi:10.1037/h0022390. PMID 14343396.

- Aronson, E., Mills, J. (1959). "The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 59 (2): 177–181. doi:10.1037/h0047195.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kelman, H. (1958). "Compliance, identification, and internalization: Three processes of attitude change". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 2: 51–60. doi:10.1177/002200275800200106. S2CID 145642577.

- Sherif, op. cit. pp. 181–279

- Scott, John Paul. Animal Behavior, The University of Chicago Press, 1959, 281pp.

- Halloway, Ralph L., Primate Aggression, Territoriality, and Xenophobia, Academic Press: New York, and London 1974. 496 pp.

- Gladwell, Malcolm (2002), The tipping point: How little things can make a big difference, Boston: Little, Brown & Co., ISBN 0-316-31696-2

External links

Media related to Social groups at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Social groups at Wikimedia Commons- Muar Talent