550 Madison Avenue

550 Madison Avenue (formerly known as the Sony Tower, Sony Plaza, and AT&T Building) is a postmodern skyscraper at Madison Avenue between 55th and 56th Streets in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. Designed by Philip Johnson and John Burgee with associate architect Simmons Architects, the building was completed in 1984 as the headquarters of AT&T and later became the American headquarters of Sony. The building consists of a 647-foot-tall (197-meter), 37-story office tower with a facade made of pink granite. It originally had a four-story granite annex to the west, which was demolished and replaced with a shorter annex in 2020.

| 550 Madison Avenue | |

|---|---|

Seen in 2007 | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Office |

| Architectural style | Postmodern |

| Location | Manhattan, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°45′41″N 73°58′24″W |

| Construction started | 1980 |

| Completed | 1984 |

| Opening | July 29, 1983 |

| Owner | The Olayan Group (Olayan America) |

| Height | |

| Roof | 647 ft (197 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 37 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Philip Johnson and John Burgee |

| Developer | AT&T |

| Structural engineer | Leslie E. Robertson Associates Cosentini Associates |

| Main contractor | William Crow Construction, HRH Construction |

New York City Landmark | |

| Designated | July 31, 2018[1] |

| Reference no. | 2600[1] |

At the base of the building is a large entrance arch facing east toward Madison Avenue, flanked by arcades with smaller flat arches. A pedestrian atrium, connecting 55th and 56th Streets midblock, was also included in the design, which enabled the building to rise higher without the use of setbacks. The ground-level lobby is surrounded by retail shops, which were originally an open arcade. The office stories are accessed from a sky lobby above the base. Atop the building is a broken pediment with a circular opening. The building has received much attention ever since its design was first announced in March 1978.

The AT&T Building at 550 Madison Avenue was intended to replace 195 Broadway, the company's previous headquarters in Lower Manhattan. Following the breakup of the Bell System in 1982, near the building's completion, AT&T spun off its subsidiary companies. As a result, AT&T never occupied the entire building as it had originally intended. Sony leased the building in 1991, substantially renovated the base and interior, and acquired the structure from AT&T in 2002. Sony sold the building to the Chetrit Group in 2013 and leased back its offices there for three years. In 2016, the Olayan Group and Chelsfield purchased 550 Madison Avenue with plans to renovate it. 550 Madison Avenue was designated a city landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2018.

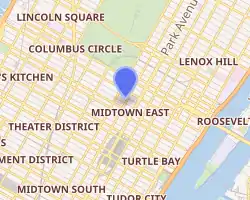

Site

550 Madison Avenue is in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. The rectangular land lot is bounded by Madison Avenue to the east, 56th Street to the north, and 55th Street to the south. The land lot covers approximately 36,800 square feet (3,420 m2),[2][3] with a frontage of 200 feet (61 m) on Madison Avenue and 189 feet (58 m) on both 55th and 56th Streets. The building is on the same city block as the Corning Glass Building to the west. Other nearby buildings include St. Regis New York and 689 Fifth Avenue to the southwest, the Minnie E. Young House to the south, the New York Friars Club and Park Avenue Tower to the east, 432 Park Avenue to the northeast, 590 Madison Avenue to the north, and Trump Tower and the Tiffany & Co. flagship store to the northwest.[2]

Prior to 19th-century development, the site had been occupied by a stream.[4] The current building directly replaced fifteen smaller structures, including several 4- and 5-story residences dating from the late 19th century. These residences had become commercial stores by the middle of the 20th century.[5] The stretch of Madison Avenue in Midtown was a prominent retail corridor during the 20th century, but new office buildings were developed on the avenue in the two decades after World War II ended.[6] Nevertheless, until the 1970s, the current site of 550 Madison Avenue was described by New York magazine as "unusually human" compared to Midtown's other office developments.[5][7]

Architecture

550 Madison Avenue, also known as the AT&T Building and later the Sony Tower, was designed by Philip Johnson and John Burgee of Johnson/Burgee. Completed in 1984 as the headquarters of telecommunications company AT&T, it subsequently served as the American headquarters of media conglomerate Sony.[8][9] Johnson had been an influential figure in modernist architecture during the late 20th century, having helped design the Seagram Building nearby in the 1950s, but he reverted to more classical motifs for 550 Madison Avenue's design.[10][11][12] The building was among Johnson and Burgee's most influential works and, according to the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC), is considered the world's first postmodern skyscraper.[13] Alan Ritchie of Johnson/Burgee was named as design manager,[14][15] while Simmons Architects was the associate architect.[15][16]

Numerous engineers and contractors were involved in the building's construction. These included structural engineer Leslie E. Robertson of Robertson & Fowler Associates; associate engineer Leroy Callender; foundation engineer Mueser, Rutledge, Johnston & DeSimone; mechanical engineer Cosentini Associates; and interior designer ISD Inc.[15][17] Frank Briscoe was the construction manager, while William Crow Construction and HRH Construction were the general contractors.[4][15][18] There were also several material suppliers.[19] In constructing the building, AT&T had requested the building use material sourced only from within the United States.[20]

Form

The primary portion of the building is the 37-story office tower along Madison Avenue, on the eastern section of the land lot. This tower is 647 feet (197 m) tall, as measured between sidewalk level and the highest point of the tower's broken pediment. It contains no setbacks.[8][9][21] Unlike other postmodernist structures with irregular ground-level plans, 550 Madison Avenue was designed as a rectangle at ground level, similar to older International Style buildings.[10] The tower stories have a footprint measuring 200 by 90 feet (61 by 27 m).[22][lower-alpha 1]

There was also a three- and four-story annex at the western end of the site.[21][24][25] At the time of 550 Madison Avenue's construction, there was a lease on the adjacent Corning Glass Building that limited the height of any structures near that building to 60 feet (18 m) in height.[12] This restriction included the westernmost lots of the AT&T site,[26] so the roof of the annex was exactly 60 feet tall.[24] Following a 2020 renovation, the annex was demolished and replaced with a single-story annex.[27]

Facade

550 Madison's articulation is inspired by classical buildings, with three horizontal sections similar to the components of a column: a base, shaft, and capital.[6][12] The facade is clad with 60,000 pieces of roughly textured pink Stony Creek granite, weighing up to 7,000 pounds (3,200 kg) apiece, supplied by Castellucci & Sons from its Connecticut quarry.[20][28][29] More than 13,000 short tons (12,000 long tons; 12,000 t) of granite is used, representing over 160,000 cubic feet (4,500 m3) of the material.[12] The stonework cost $25 million in total[29][30][31] and required an additional 6,000 short tons (5,400 long tons; 5,400 t) of steel to support it.[32] Varying reasons are given for the use of granite. Johnson considered pink granite as "simply the best" type of stone,[12][20] and Ritchie said the Stony Creek pink granite had "more character" than granite for other sources.[20] Conversely, Burgee said the pink color was chosen to contrast with 590 Madison Avenue, the gray-green granite structure built simultaneously by IBM to the north.[33]

The granite facade helped to reduce energy compared to the glass curtain walls used on many of the city's contemporary skyscrapers.[20][34] Only about one-third of 550 Madison Avenue's facade is clad in glass. At the time that the plans were announced in 1978, Johnson said this would make 550 Madison Avenue the city's "most energy-efficient structure".[20][35] The windows are recessed into granite surrounds that are up to 10 inches (250 mm) deep.[12] The architects had wanted the windows to be deeper, but this was not possible because of the cost of the granite. Additionally, the round mullions of the original design were given a more rectangular shape, and the window arrangement was dictated by the interior use.[36] The building also includes more than 1,000 pieces of brass manufactured by the Chicago Extruded Metals Company.[29]

Base

The main entrance is on Madison Avenue and consists of an archway measuring 116 feet (35 m) high by 50 feet (15 m) wide, with a recess 20 feet (6.1 m) deep. Within the archway is a 70-foot (21 m) arched window,[37] topped by a circular oculus with a 20-foot (6.1 m) radius.[38][21][39] Both windows have glazed glass panels and vertical and horizontal bronze mullions. These windows are surrounded by stonework with rhombus tiles. The side walls have smaller round arches and rectangular stonework, while the top of the arch contains recessed rectangular lights.[21] According to architectural writer Paul Goldberger, the arch may have been influenced by the Basilica of Sant'Andrea, Mantua.[40][41][42] AT&T said the arch was supposed to make the building appear dominant and give it "a sense of dignity".[37] To the left and right of the main entrance arch are three flat-arched openings, measuring 60 feet (18 m) tall by 20 feet (6.1 m) wide, with voussoirs at their tops.[43]

Originally, 550 Madison Avenue had an open-air arcade north and south of the central archway, extending west to the public atrium behind the building.[24][39][43] The arcade measured 60 feet high;[43][25] it was conceived as a 100-foot-high space but was downsized "for reasons of scale".[39][44][lower-alpha 2] The presence of the arcade allowed for what Johnson described as "a more monumental building" with more floor area.[37][45] The space is supported by 45 granite columns weighing 50 short tons (45 long tons; 45 t) apiece.[32] The granite columns are designed to resemble load-bearing columns;[20][22] they use thicker stone to represent solidity, and they contained notches to represent depth.[46] There was initially no retail space on the Madison Avenue front because, according to critic Nory Miller, "AT&T didn't want a front door sandwiched between a drug store and a lingerie shop."[44] After the AT&T Building's opening, the arcade gained a reputation for being inhospitable, dark, and windy.[47][48] Following a renovation in the 1990s, the arcade was enclosed with recessed display windows with grids of bronze mullions.[43] When the windows were replaced in 2020, transparent mullions were added.[49]

At the extreme ends on Madison Avenue are single-story flat arches surmounted by flagpoles. These lead to recessed passages along 55th and 56th Streets, which act as an extension of the sidewalks on these streets. There are multicolored granite pavement tiles within these passages.[50] The 56th and 57th Street facades contain flat arches measuring 16 feet (4.9 m) tall, supported by granite-clad piers at regular intervals. Just above each flat arch is a circular opening with canted profiles, atop which are four vertically aligned rectangular openings.[50] The circular openings were carved in false perspective, making the arcades on either side appear deeper than they actually were.[51]

The granite wall of the original annex on 55th Street was windowless and contained three garage doors. The granite wall on 56th Street had a tall window bay, a garage door, and a cornice.[50]

Shaft

The intermediate stories of the office tower are divided on all sides into several window bays, each of which contains one single-pane window on each floor. The Madison Avenue and western facades are identical to each other, as are the 55th and 56th Street facades.[50] The west and east facades contain nine bays each. The center bay is eight windows wide, flanked by three sets of four windows on either side, as well as a wide single window at the extreme north and south ends. Granite spandrels separate the windows on different stories, except at the executive offices in the top three stories, which contained bays with glazed curtain walls.[50] The north and south facades contain six bays each, separated by granite piers.[23] The granite panels contain real and false joints to give a consistent appearance.[52]

The granite panels are typically 2 or 5 inches (51 or 127 mm) thick, while the mullions are 6 or 10 inches (150 or 250 mm) square.[52] The granite panels are extremely heavy, with many panels weighing over 1 short ton (0.89 long tons; 0.91 t), so they could not be hung onto the steel frame as with typical skyscrapers. Leslie Robertson determined that each granite panel had to be anchored individually to the steel frame, and the mounting apparatus had to be strong enough to support the weight of two panels.[31][18]

Pediment

At the roof is a broken pediment, consisting of a gable that faces west toward Fifth Avenue and east of the Madison Avenue. The center of the pediment contains a circular opening that extends the width of the roof.[11][38][50] The opening measures 34 feet (10 m) across.[11][53] Within the opening are ribbed slats, which contain vents for the building's HVAC system; according to Johnson, the vents would create steam puffs when there was a certain proportion of moisture in the air.[39] The remainder of the gable is trimmed with a stone coping.[38][50] The granite slabs are suspended from a steel parapet.[52]

The pediment, inspired by classical designs, was included to unify the symmetrical facades.[39][53] Johnson may have also been inspired by his dissatisfaction with the Citigroup Center's sloped roof, visible from his own office in the Seagram Building.[44] Johnson/Burgee wanted to make the roof recognizable upon the skyline, and they decided upon a pediment because it was well suited for the narrow tower.[53] During the design process, Johnson/Burgee had considered various ornamental designs before deciding on the circular notch.[39][53] One of the previous buildings on the site, the Delman Building at 558 Madison Avenue, had contained a similar broken pediment, although Johnson repudiated claims it influenced 550 Madison Avenue's rooftop.[16][24][54] Instead, Johnson claimed to have been inspired by Al-Khazneh in the Jordanian city of Petra.[37][55]

Features

550 Madison Avenue has a gross floor area of 685,125 square feet (63,650.2 m2).[2] The superstructure is composed of steel tubes, except at the base, where the superstructure is composed of shear walls connecting the sky lobby and foundation.[15] The steel beams were constructed by Bethlehem Steel.[18][19][32] The colonnade at the base was insufficient to protect against wind shearing. As a result, the core of the tower contains two concrete and steel "shear tubes", each measuring 25 by 31 feet (7.6 by 9.4 m).[32] In addition to its 37 above-ground stories, the building is designed with three basements.[4] One of these basement levels contained a 45-spot parking garage, originally meant for AT&T board members, as well as vehicular elevators for delivery trucks.[56]

Lobbies

550 Madison Avenue contains a main lobby just inside the large arch on Madison Avenue. The lobby measures 50 by 50 feet (15 by 15 m)[44] and originally contained a floor made of black-and-white marble, as well as walls made of granite.[57][58] The floor pattern was inspired by the designs of British architect Edwin Lutyens.[36][44][59] The lobby's ceiling was a groin vault.[60] After a 2020 renovation, the lobby was redesigned with large windows at its western end, as well as decorative materials like terrazzo, leather, and bronze mesh.[57][58] The terrazzo floors incorporate some of the original marble flooring. The lowest portions of the lobby wall are decorated with the mesh, while the rest of the walls are covered in white marble.[61] Solid Sky, a 20,000-pound (9,100-kilogram) spherical blue sculpture by Alicja Kwade, hangs in the lobby.[62][63]

Spirit of Communication (also Golden Boy), a 20,000-pound (9,100-kilogram) bronze statue[64] that stood atop AT&T's previous headquarters at 195 Broadway,[60][64] was removed from that building in 1981 and relocated to 550 Madison Avenue's main lobby in 1983.[65] The artist Evelyn Beatrice Longman created the statue in 1916.[25][66] It depicts a 24-foot-tall (7.3 m) winged male figure on top of a globe, wrapped by cables, clutching bolts of electricity in his left hand.[66] The statue was repainted in gold leaf when it was relocated to 550 Madison Avenue.[24][29][39] The statue was placed on a pedestal inside the lobby, with the circular window atop the main entrance arch seeming to form a halo above the statue.[39][44] It was relocated to AT&T's Basking Ridge, New Jersey, facility in 1992.[67]

One wall of the main lobby contained an arcade with Byzantine-inspired column capitals,[59] behind which was an elevator lobby with bronze elevator doors.[60] From the main lobby, elevators led to a sky lobby on the seventh floor, 77 feet (23 m) above ground level.[22] The sky lobby was clad with veined Breccia Strazzema marble.[22][25][60] It originally contained the building's security checkpoints.[24][39] As designed, the sky lobby had sparse decoration.[48][68][69] Between 1992 and 1994, after Sony acquired the building. Dorothea Rockburne was hired to paint two abstract frescoes, and Gwathmey Siegel redesigned the lobby with wooden paneling and black glass.[68][69] The frescoes, entitled "Northern Sky" and "Southern Sky", measure 30 by 30 feet (9.1 by 9.1 m) and consist of red and yellow patterns with spheres.[70]

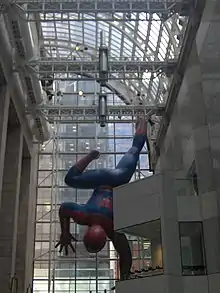

Atrium and annex

Between the annex to the west and the main tower to the east was an atrium measuring 40 feet (12 m) wide by 100 feet (30 m) tall.[26] The public atrium between the annex and the tower was originally covered by a metal and glass roof, the ceiling of which was a half-barrel vault (shaped as a quarter-circle).[24][50][60] The presence of the atrium not only allowed additional floor area but also was aligned with the atrium in the IBM Building at 590 Madison Avenue.[26][60] According to Burgee, he wanted the atrium to have a distinct identity from the office tower.[26] The atrium, designed as an open-air pedestrian pathway, was enclosed in the 1990s when Sony moved to the building.[47] A large television screen was installed with this renovation.[71][72]

In the early 2020s, the roof was replaced by a lighter metal and glass canopy.[73][74] A new garden called 550 Madison Garden was constructed within the atrium. The garden will contain shrubs, trees, bulbs, and perennial plants and will be split into five sections.[75] The garden's greenery will extend onto the roof of a rebuilt annex to the west. The atrium also includes a waterfall and seating, as well as circular floor pavers to demarcate various parts of the space.[73][74][75]

The parking garage and truck elevators were in the annex, with a ramp to the garage from 56th Street and the elevators from 55th Street.[51] The annex had its own lobby near 56th Street.[51] There was also retail space within the original annex,[51] facing the western wall of the atrium.[22][44] The annex originally contained Infoquest, an AT&T technology exhibit, which opened in 1986[76] and operated until about 1993.[68] The annex became the Sony Wonder museum in 1994; it was open on Tuesdays through Saturdays, and Sony described the free exhibits as a "technology and entertainment museum for all ages".[77] The original annex was demolished as part of a 2020 renovation, and a one-story replacement structure was built in its place.[27]

Office spaces

The office stories cover the fifth through 33rd stories.[25] 550 Madison's height is equivalent to that of a 60-story building with 8-foot (2.4 m) ceilings. However, the ceilings at 550 Madison Avenue were typically designed to be 10 feet (3.0 m) high, and executive suites had ceilings of 12 feet (3.7 m). At the time, computer hardware required taller ceilings than was usual.[56] As originally designed, the acoustic ceiling panels had air conditioning vents and minimal ceiling lighting, as each worker's desk had task lighting.[22] In addition to offices, the building contained a two-story auditorium at the fifth and sixth stories, as well as a CCTV studio at the eighth story.[31][56]

The office stories were generally less ornately decorated than the lobbies, but the 33rd- and 34th-floor executive offices contained ornate wood paneling.[48] AT&T had requested that the highest-quality materials be used,[78] although escalating costs during construction led to the substitution of cheaper material in some places.[30] The acoustic ceilings were manufactured by the Industrial Acoustics Company,[19][29] which manufactured 325,000 square feet (30,200 m2) of perforated steel panels clad with vinyl. In addition, AT&T bought $5.5 million worth of honey-colored Burmese teak furnishings such as paneling, trim, and doors from L. Vaughn Company, which hired 75 workers to supply the rare wood. The decorative materials used in the building included Burmese teak document cabinets, Turkish onyx elevator panels, Chinese silk in the employee dining room, and Italian leather in the executive dining room. Italian marble was used for the executive staircases.[29]

After Sony moved into the building in 1992, Gwathmey Siegel renovated the interior with additional staircases, as well as doors topped with glass panels. The offices were refitted with sound systems and Sony videocassette recorder systems. The spaces were generally more flexible than under AT&T's occupancy, as they were meant to accommodate record and movie production. A conference center for Sony was also installed on the 28th floor.[68][79] The AT&T executive offices on the 35th floor were retained and an executives' dining club called the Sony Club was opened within the space.[68][79][80] By 2020, the seventh floor was being renovated into amenity space, including a food hall, fitness center, library, screening room, and pool hall.[81]

History

AT&T was established in 1885[82] and had occupied a headquarters at 195 Broadway in Lower Manhattan since 1916.[3][83] In the subsequent decades, AT&T became the world's largest corporation,[82] and maintenance costs on the headquarters had increased significantly.[84] With its continued growth, AT&T acquired land for a new facility in Basking Ridge, New Jersey, in 1970,[85] although the company repudiated claims that it was fleeing for the suburbs.[3][86] Furthermore, John D. deButts, who became AT&T's CEO in 1972, wished to construct a new Midtown headquarters as a monument to the company and to boost his own name recognition.[3][87] The 195 Broadway headquarters had a capacity of only 2,000 workers, but AT&T had 5,800 headquarters workers by the mid-1970s, most of them in New Jersey.[88]

Site acquisition

AT&T began looking for a Midtown site in the early 1970s, hiring James D. Landauer Associates to assist with site selection. It wished to build a site near Grand Central Terminal but eschewed Park Avenue as being too prominent. The western blockfront of Madison Avenue between 56th and 57th Streets was being acquired by IBM, which refused to give up its lot to AT&T.[87] On the block immediately to the south, Stanley Stahl had paid $12 million since 1970 for a lot of 23,000 square feet (2,100 m2).[89] On Stahl's block, AT&T acquired seven buildings in late 1974, followed by two adjacent buildings to the west in 1975, the latter of which were acquired in anticipation that AT&T would be allowed to construct extra space.[3] Stanley W. Smith, president of the 195 Broadway Corporation, paid Stahl $18 million for his assemblage in October 1975.[88][90] The land value appreciated significantly in the following years; by 1982, Stahl's plot alone was worth $70 million.[84][90]

To save time and limit inflation-related costs, AT&T awarded some construction contracts before certain design details were finalized.[56] Demolition permits for the site had been approved by 1976, but because of subsequent delays, the vacant lot was temporarily considered for a park or taxpayer building.[16] The Alpine Wrecking Corporation was hired to dismantle the existing structures. The company removed non-load-bearing walls, salvaged recyclable materials, demolished the structures' upper stories by hand, and finally used machinery to destroy the lower stories. The two buildings nearest the Corning Glass Building were temporarily preserved to allow that building's fire code rating to be retained.[28]

Planning and design

Around 1977, a committee of three AT&T officials and three officials from Smith's offices mailed questionnaires to twenty-five architects or design firms which the executives deemed "highly qualified".[16][90][91] Thirteen of the recipients responded.[90] Conversely, Johnson/Burgee recalled that they set aside the questionnaire until AT&T called them two weeks afterward.[90][91] Smith visited eight candidates and picked three finalists: Johnson/Burgee, Roche-Dinkeloo, and Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum.[16][91] The three finalists were to give presentations to the committee and high ranking officials.[92] Johnson recalled that he did not have an elaborate presentation, but instead brought photographs of his past work and came with Burgee. According to AT&T officials, "there was no close second" candidate;[93] Smith subsequently recalled that Johnson/Burgee were open to different design ideas.[92]

On June 17, 1977, the day after the presentations, The New York Times reported that AT&T had hired Johnson/Burgee to design a 37-story headquarters on the site.[6][94] Johnson was quoted as saying that he wanted the new headquarters to be a "landmark" representing the company.[16][94] The Wall Street Journal reported shortly afterward that Johnson was conducting a "feasibility study" for the headquarters.[95] AT&T mandated that Johnson/Burgee select an associate architect as per the provisions of the Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972. Harry Simmons Jr., head of a small African-American firm, was selected out of seven interviewees from a field of 28 candidates. Simmons's firm was tasked with designing twenty percent of the overall architectural detail.[16]

According to design manager Alan Ritchie, DeButts explained "what he wanted in broad terms" but gave wide latitude to the final design.[14][92] Johnson and Burgee examined various structures, such as the entries to the Tribune Tower design competition, for inspiration.[14][96] Judith Grinberg created a 7-foot-tall (2.1 m) sketch of the AT&T Building's facade "to interpret [Johnson's] design intent";[59][97] the sketch was sold to London's Victoria and Albert Museum in 2010.[98] In addition, Howard W. Swenson created numerous styrofoam models for the building and helped to refine the design details.[22][53] The New York City Department of Buildings received blueprints for the new headquarters in January 1978.[46] A Times editorial that month praised the AT&T project, as well as the neighboring IBM development at 590 Madison Avenue, as a "declaration of corporate commitment" to New York City, which had then recently rebounded from its fiscal crisis.[99]

AT&T announced its official plans on March 30, 1978, in front of New York City Hall.[35][100] A rendering of the headquarters was shown on the front page of the next day's Times.[6][16] Mayor Ed Koch described the project as "a strong vote of confidence" in the city's future,[101] and the news media characterized it as part of a trend of midtown revitalization.[102][103] AT&T initially expected construction to begin in late 1978 and be complete by 1982 at an estimated cost of $60 million.[101][lower-alpha 3] The design, particularly the broken pediment, received widespread media attention, prompting AT&T to reexamine the plan in detail before deciding to proceed without modifications.[44][104] In late 1978, the project received several floors' worth of zoning "bonuses" and exemption from setback regulations, in exchange for public space, a three-story communications museum, and a covered arcade on Madison Avenue.[37][105][lower-alpha 4] The next month, Johnson decided that Stony Creek pink granite would be used on the AT&T Building's facade.[44]

Construction

Construction started in December 1978 with the excavation of the foundations.[18] The same month, AT&T received a $20 million tax abatement toward the construction cost.[106] The foundation excavation cost $3.1 million and largely consisted of blasting into the underlying bedrock.[4] The detonations used about 50,000 pounds (23,000 kg) of Tovex gel. The underlying rock layer was made of mica schist, the composition of which was unpredictable if detonated, so about 8,000 small blasts were used to excavate the foundation.[28] The resulting hole was 45 to 50 feet (14 to 15 m) deep.[18][28] Excavations were ongoing in February 1979 when deButts was replaced by Charles L. Brown as AT&T CEO. Brown, who was less enthusiastic about a grand headquarters than deButts had been, sought a review of the project, but construction continued nonetheless.[44][107] In the face of rising construction costs, the architects were compelled to swap some of the expensive materials with cheaper materials, such as replacing granite in the elevator cabs with wood.[30][32]

Steel for the superstructure was constructed starting in March 1980.[18][32] Before the steel beams were placed, the workers erected the shear tubes at the building's core, as well as the 50-ton granite columns supporting the base. Because the steel only started above the sky lobby, atop the base, the workers climbed through the shear tubes to complete the sky lobby, then installed the steel crane in place. Furthermore, the IBM Building was simultaneously under construction on 56th Street, limiting access on that street.[32] The project only had one construction manager, Frank Briscoe. Shortly after work started, two additional foremen were hired after Local 282, the union whose workers were constructing the building, threatened a strike.[45] In December 1980, Paul Goldberger wrote for The New York Times that "the arch is beginning to take shape".[108]

At its peak, the project's three foremen had to balance the requests of about "three dozen powerful prime contractors and 150 subcontractors and suppliers", according to Inc magazine.[18][29] Workers from more than 70 trades were involved in the construction of the building.[18][32] The cladding was erected starting in September 1981, several months behind schedule.[18][109] The workings were so complex that even the facade cladding required the involvement of members of four construction unions.[29] The building topped out on November 18, 1981.[18] Because of the hastened pace of construction, the contractors made some mistakes; for instance, electrical ducts had to be carved into the concrete floors after they were built.[31] By late 1982, the work was one year late and $40 million over budget.[18][31]

Completion and early years

Throughout nearly the entire development process, AT&T faced an antitrust lawsuit from the United States Department of Justice.[30][90] The parties reached an agreement in January 1982, with AT&T consenting to divest its Bell System effective January 1, 1984.[30][110] Shortly after this agreement, AT&T decided to seek a lessee for 300,000 sq ft (28,000 m2) of space on the 7th through 25th floors, nearly half the space in the building.[111] AT&T sought to rent out the space for as much as $60 per square foot ($650/m2) but had few potential takers.[30][111] The company had expected to relocate as many as 1,500 employees, but the impending divestiture meant it would only be moving 600 employees into 550 Madison Avenue.[111] In early 1983, AT&T reneged on its rental proposal after city government officials warned AT&T officials that the building's tax exemption could be canceled if AT&T were to receive rental income.[112]

The first occupants moved to their offices on July 29, 1983,[18] and the Spirit of Communication statue was dedicated two months later, with full occupancy expected by the time of the Bell System divestiture at the end of the year.[65] However, only three of the office stories were occupied by the end of the year.[18] With the Bell System divestiture, about 1,200 employees were moved from 195 Broadway to 550 Madison Avenue by January 1984. That month, AT&T's longtime advertising agency N. W. Ayer & Son displayed a large welcome message from its own offices nearby.[113] New York magazine reported in February 1984 that the executive offices were not occupied and that full completion was not expected until that May.[114] The completion of 550 Madison Avenue took place sometime in 1984 but was overlooked by the media, which instead publicized the divestiture.[18] The building ultimately cost $200 million, a rate of about $200 per square foot ($2,200/m2),[18][29] although New York placed the cost as high as $220 million.[114] Despite the high cost of construction, the Bell System divestiture meant that AT&T never fully occupied 550 Madison Avenue.[115][116]

In early 1984, AT&T indicated that, rather than constructing a museum in the annex for bonus zoning, it would use the annex for a showroom.[114] The change of plan came following the Bell divestiture and the reduced presence it expected to have at the building.[26][105] After the city firmly opposed the move, AT&T agreed to construct a three-story exhibition space within the annex.[117] In exchange, AT&T was granted a $42 million, ten-year tax abatement that August.[118][119] The museum, which was named Infoquest Center, opened in May 1986.[26][76] That September, AT&T announced it planned to move up to 1,000 of its 1,300 employees to Basking Ridge, placing at least 600,000 square feet on the market. The company was reconsidering leasing out its Madison Avenue headquarters by early 1987.[120][121] After Koch threatened to rescind the entire tax abatement, AT&T agreed to limit the relocation to 778 employees.[122] The fine dining restaurant The Quilted Giraffe relocated to the building in June 1987.[123]

Sony ownership

Having decreased in size substantially, AT&T sought to sublet 80 percent of the space at 550 Madison Avenue in January 1991. At the time, AT&T wanted to move most employees to cheaper space.[124][125] AT&T had signed a tentative 20-year lease with Sony by that May, although neither company would confirm the rumor at the time.[126] Sony signed a 20-year lease agreement for the entire building that July, including an option to purchase 550 Madison Avenue. AT&T also forfeited $14.5 million of tax abatements to the city government, equivalent to the taxes forgiven since 1987.[115][127][128] The refunded tax abatements were used to fund programs at the financially distressed City University of New York for the 1991–1992 school year.[129] AT&T relocated its headquarters to 32 Avenue of the Americas, its long-distance telephone building in Lower Manhattan, and removed the Spirit of Communication statue.[130] With the sale of the building, Burgee said, "The period of making image buildings for companies appears to be over."[131]

Renovation

After Sony leased the building, it became known as the Sony Tower. In early 1992, Gwathmey Siegel designed a renovation of the base, with Philip Johnson as consultant. The arcade space would be converted into retail space and, in exchange, the atrium would be expanded with new planters and public seating.[116][132] Edwin Schlossberg was hired to design the new storefronts and redesign the annex.[72][133] Sony expected that 8,727 sq ft (810.8 m2) of the arcade could be converted into stores at a rate of $200 per square foot ($2,200/m2). According to Sony, the arcades were "dark, windy and noisy", and a conversion to commercial space would provide "retail continuity" with the remainder of Madison Avenue.[134]

Johnson was not overly concerned about the closure of the arcade, saying, "It isn't that my ideas have changed. The period has changed."[47] The plan did face some opposition: the original associate architect Harry Simmons Jr. said that a "valued and useful space" would be razed, while Joseph B. Rose of the local Manhattan Community Board 5 said it would create "a dangerous precedent" for converting public plazas to commercial space.[47][135] David W. Dunlap of The New York Times said the changes were "unquestionably an improvement" not only aesthetically, but also functionally.[47][136] The New York City Planning Commission had to review and approve the proposal.[115][116] While the plans would result in a net loss in public space, they would increase the overall zoning bonus.[47][79][lower-alpha 5] The commission approved slightly modified plans in September 1992, which retained small portions of the arcade.[47] Sony bought out the Quilted Giraffe's lease and the restaurant closed at the end of 1992.[137]

The Sony Tower was renovated between 1992 and 1994. Windows with bronze gridded frames were installed to close off the atrium, which became Sony stores, and the annex was converted into the Sony Wonder technology museum.[133] The annex was completely gutted because, under guidelines set by the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the existing ramps and passageways were too steep.[138] Inside, Dorothea Rockburne was commissioned to paint two fresco murals for the formerly bare sky lobby, and additional staircases, conference centers, and offices were installed on the office stories.[68][69] Barry Wine, founder of the Quilted Giraffe, was hired as the chef for the building's private dining club.[69][139]

Use

The new atrium and retail spaces, known as Sony Plaza, were completed in 1994, and the Sony Wonder museum opened in the annex that May.[72][69][133] The company name was prominently displayed in Sony Plaza: the company logo was emblazoned on the jackets of the atrium's security guards, and banners with Sony's name were displayed.[71] In its first year, the converted Sony retail space at ground level received less profit than expected, prompting Sony Plaza Inc. to hire a new general manager in 1995.[140] The atrium was criticized for being inhospitable to the homeless, as private security guards had been hired to patrol the space.[141]

Sony leased four stories at 555 Madison Avenue immediately to the east in February 1995.[142] By the following year, Sony was renovating its space within 555 Madison Avenue; the company installed fiber-optic cables under Madison Avenue to connect its two buildings, and it installed microwave communications equipment atop 555 Madison Avenue. Sony had consolidated most of the operations for its Sony Music Entertainment division at the Sony Tower on 550 Madison Avenue, for which The New York Times noted that "such high-profile and elaborate space is appropriate and necessary."[143] This was part of a move to consolidate Sony's United States operations away from the Sony Corporation of America, which had overseen Sony Pictures and Sony Music, and give more control over the United States operations to executives in Japan.[144] It was described by The Wall Street Journal as indicative of "a long-term commitment to the area".[145]

In 2002, Sony exercised its option to purchase the building from the cash-strapped AT&T for $236 million, or $315 per square foot ($3,390/m2). This was a relatively cheap price in comparison to the building's location in Midtown Manhattan.[146][147] Two years later, Sony contemplated selling the building once its merger with Bertelsmann was completed.[148] Part of the Sony Wonder museum was renovated in 2008 and reopened the following year.[149] An accumulation of ice dislodged from an upper floor after a February 2010 blizzard, breaking the glass ceiling of the atrium and injuring several inside.[150][151]

Chetrit purchase

By 2012, Sony was looking to sell off the Sony Tower, as the company perceived that the costs of keeping its American headquarters in Midtown were too high.[152] At the time, the company faced large losses; in the fiscal year ending March 2012, it had reported $5.7 billion in revenue losses.[153] Potential buyers started submitting bids for the Sony Tower in December 2012.[154][155] Sony received over 20 bids, including from Joseph Sitt's Thor Equities, Mitsui Fudosan, and a partnership led by the Brunei Investment Agency.[152] All of the bids included converting at least part of the space to hotel or condominium use.[156] In January 2013, Sony announced it would sell the building to Joseph Chetrit's Chetrit Group for $1.1 billion, leasing back its offices there.[157][158] Shortly afterward, Sony filed eviction proceedings against Joseph Allaham, a longtime tenant and Chetrit's friend, who operated a pizzeria and a restaurant in the base.[159][160] Allaham ultimately decided to relocate his restaurant and retain his pizzeria.[161]

The Chetrit Group planned to redevelop the Sony Tower with condominiums and the first Oetker Collection hotel in the United States.[162][163] In February 2015, the developers filed a condominium offering that called for 96 residences, which would be sold at a combined total of $1.8 billion.[164] The offering included what was then considered Manhattan's most expensive residence, a three-story penthouse in the upper stories costing $150 million.[165][166] Dorothea Rockburne expressed concern that the developers would not adequately preserve two of her frescoes in the sky lobby, which was set to be converted into the hotel's lobby.[167] Sony permanently closed the Sony Wonder Technology Lab in January 2016. Over the following months, Sony moved its headquarters and stores south to 11 Madison Avenue.[168][169]

Olayan redevelopment

Following a declining real estate market in the 2010s, Chetrit abandoned its condominium conversion plan.[170] Chetrit sold the building to Olayan Group and Chelsfield in April 2016 for $1.4 billion, relinquishing the "Sony Tower" name.[171][172] Olayan and Chelsfield announced plans to rebrand 550 Madison Avenue and reconfigure the existing space, which was then empty besides Allaham's pizzeria.[173] A group of banks including ING Group, Bank of East Asia, Crédit Agricole, Société Générale, and Natixis provided $570 million in financing to facilitate the redevelopment.[174] The pizzeria closed in September 2017.[175]

In late October 2017, the Olayan Group announced plans to renovate the building with designs by Snøhetta. The firm planned to add a glass curtain wall along the base on Madison Avenue, as well as demolish the arcade and annex on the western end of the site, replacing it with a garden.[176][177] The renovation was anticipated to cost $300 million and raise rents at the building to between $115 and $210 per square foot, some of the highest office rents in New York City.[178] Several architecture critics, architects, and artists voiced their opposition to the plans,[179] and a November protest and petition drew media coverage.[180][181] Shortly afterward, the LPC voted to calendar the building for consideration as a landmark.[182][183] Though there were efforts to preserve the significant interiors,[184] demolition of the building's original ground floor lobby began in January 2018.[185][186] The LPC determined that the lobby was not eligible for interior landmark status because its design had changed significantly when Spirit of Communication was removed and the arcades were enclosed.[187][188] By that February, the original lobby had been demolished.[188]

On July 31, 2018, the LPC voted unanimously to designate the exterior as a New York City landmark.[189][190][191] Filmmaker and cultural heritage activist Nathan Eddy, who petitioned to preserve the original status, described the designation as "an astonishing and marvelous victory".[189] As a result of the landmark status, the plans for the lobbies were modified so that the western end of the ground-floor lobby faced the atrium, and Rockburne's frescoes were to be mounted on the sky lobby.[49][192] These new plans were approved by the LPC in February 2019.[193][194] The original plan to demolish the annex and atrium was also modified. In Snøhetta's updated plan, the atrium would be planted with greenery and connected to 717 Fifth Avenue, and the atrium's roof and the annex would be replaced.[73] The New York City Planning Commission approved the modified design for the plaza in January 2020.[74][195] Olayan executive Erik Horvat said the renovation would help 550 Madison "compete against Hudson Yards, One Vanderbilt and the best buildings in the city".[196]

The canopy over the midblock atrium was being installed by August 2021.[197] The new lobby was completed that October,[61][198] at which point 550 Madison Avenue was 45 percent leased.[61] The Chubb Group leased ten floors the next month, becoming the first confirmed tenant within the renovated building.[199][200] Luxury fashion retailer Hermès leased three stories in February 2022 for its headquarters,[201][202] and the first plantings were delivered to the rebuilt atrium that May.[75]

Impact

Critical reception

_11_-_Steam_Funnel.jpg.webp)

The AT&T Building received much publicity from architectural critics from the time plans were announced in March 1978.[104][203] When the building was announced, Paul Goldberger it "post-modernism's major monument", but felt that the broken pediment "suggests that a joke is being played with scale that, may not be quite so funny when the building [...] is complete".[24][42][104] Ada Louise Huxtable described the design as "a monumental demonstration of quixotic aesthetic intelligence rather than art"[104][204] and dubbed it 1978's "non‐building of the year".[205][206] Michael Sorkin of The Village Voice dismissed the building as merely a "Seagram Building with ears".[23][207] Architects and members of the public wrote letters about the design, many of which were sardonic and disapproving.[208] Robert Hughes of Time magazine called it "peculiar rather than radical"[203][209] but said it gave other designers permission "to build their own monuments of the hybrid" postmodernist style.[206][209]

Much controversy surrounded the roof's broken pediment.[6][10] Goldberger was the first person to publicly characterize the pediment as "Chippendale", after the British manufacturer's furniture, but said the term had been first used by Arthur Drexler of the Museum of Modern Art,[40][44] who did not want to be associated with the nickname.[46] The pediment gained more notice elsewhere. Chicago Tribune architecture critic Paul Gapp wrote that the pediment had "made instant history" and incited "a natural uproar",[210] and the Atlanta Constitution quoted various architects who said the design "couldn't possibly succeed" and was "a tragedy" if taken seriously,[211] Conversely, The Baltimore Sun expressed optimism that the design would inspire similar structures in Downtown Baltimore.[212] The cynical response to the initial plans led Johnson to publicly defend his plan in 1978, both in a New York Times op-ed[206][213] and a speech for the American Institute of Architects.[214] Der Scutt, architect of the neighboring Trump Tower, said in 1981 in response to criticism of 550 and 590 Madison Avenue: "I can't find anything oppressively hideous in IBM or AT&T. What is wrong with 'a showcase of superscale' in a city that prides itself as being culturally ecstatic about it's [sic] skyscrapers?"[215]

When 550 Madison Avenue was nearly finished, Goldberger re-appraised it as an important structure architecturally, though he said the completion "threatened to be something of an anticlimax".[65][203][216] Ellen Posner of The Wall Street Journal said "It is not at all surprising that some of the original negative votes have been recast as positive".[217] After the building was completed, it was received much more positively than during its construction.[116] Susan Doubliet wrote for Progressive Architecture that the building was "more pleasure to passers-by than anyone would have predicted", while also stating that "more was expected" of the disorganized design.[22][116] Art historian Vincent Scully said 550 Madison Avenue "takes charge of the street" and that the pediment "has the effect of making us wonder why we ever allowed people to build skyscrapers with flat tops".[116][218] Conversely, in a 1987 New York magazine poll of "more than 100 prominent New Yorkers", 550 Madison Avenue was one of the ten most disliked structures in New York City.[219] Huxtable disliked the entrance lobby, which she called "an oddly awkward and unsatisfactory space, distorted by its overreaching height and narrow dimensions".[220]

Sony's redesign of the building's atrium and arcades in the 1990s received mixed criticism.[79][133] Some onlookers praised the openness of the atrium and retail spaces; one visitor interviewed by The New York Times regarded the changes as akin to a television commercial in exchange for a public benefit. Others disapproved of the many references to Sony, including Ruth Messinger, Manhattan's borough present at the time, who perceived the atrium as "overly commercial".[72] Progressive Architecture characterized the atrium as "not so bad" aesthetically but said that Sony's commercial amenities were not necessarily a sufficient tradeoff for public space.[221]

Architectural significance

With ornamental additions such as the pediment and ground-level arch, the building challenged architectural modernism's demand for stark functionalism and purely efficient design.[38] Wolf Von Eckardt wrote for The Washington Post in 1978, "I believe Johnson may well unite contemporary architecture again and lead it out of both the glass box and the concrete sculpture to a new ecumenic gentility."[222] Similarly, critic Reyner Banham thought the building had the potential to reshape architecture in New York City and in the postmodern era.[115][116][223] The effect on the public at large has been described as legitimizing the postmodern movement globally. Johnson described the building as "a symbolic shift from the flat top" of International Style skyscrapers like the nearby Lever House.[35] In a conversation with LPC researchers, Burgee said he received numerous letters from younger architects who expressed their gratitude that "the previous rules no longer apply".[115] The design also influenced some of Johnson and Burgee's other works during the 1980s.[17]

For his design of the AT&T Building, Johnson received the Bronze Medallion from the city government in 1978.[82] Johnson also received the 1978 Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architects, and he was the first architect to receive a Pritzker Architecture Prize in 1979.[224]

See also

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- List of tallest buildings in New York City

- AT&T Corporate Center

- Sony Building (Tokyo)

References

Notes

- The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission describes the tower stories as measuring 200 by 100 feet (61 by 30 m), but also describes the 55th and 56th Street facades as measuring 90 feet (27 m) wide.[23]

- The arcade height is also cited as 65 feet.[44]

- According to The New Yorker, the initial projected cost was $110 million, though this cost was not dated.[89]

- AT&T was granted permission to add 81,928 square feet (7,611.4 square meters), about four stories, in exchange for the open public space and communications museum. The company was given an additional 43,000 sq ft (4,000 m2), or two stories, for creating a 14,000 sq ft (1,300 m2) covered arcade along Madison Avenue with include seating and retail kiosks.[105]

- The building received 3 square feet of additional interior space for every square foot of arcade space, and it received 11 square feet of interior space for every square foot of midblock atrium space. About 10,560 square feet (981 m2) was to be removed from the arcade, so 31,680 square feet (2,943 m2) of interior bonus would be forfeited. About 4,106 square feet (381.5 m2) was to be added to the midblock atrium, so 45,166 square feet (4,196.1 m2) of interior bonus would be added.[47]

Citations

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 1.

- "550 Madison Avenue, 10022". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 10.

- Barbanel, Josh (July 8, 1979). "The Skyscraper Business: Getting Off the Ground". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, pp. 10–11.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 493.

- Unger 1982a, p. 44.

- "Sony Tower". Emporis. Archived from the original on March 17, 2008. Retrieved July 12, 2008.

- "550 Madison Avenue - The Skyscraper Center". Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. October 11, 2019. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Stichweh, Dirk (2016). New York Skyscrapers. Prestel Publishing. p. 137. ISBN 978-3-7913-8226-5. OCLC 923852487.

- Nash, Eric (2005). Manhattan Skyscrapers. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-56898-652-4. OCLC 407907000.

- Unger 1982a, p. 51.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 8.

- Unger 1982a, p. 49.

- Doubliet 1984, p. 75.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 11.

- Johnson et al. 2002, p. 243.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 12.

- Doubliet 1984, p. 168.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 15.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 6.

- Doubliet 1984, p. 70.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, pp. 14–15.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 494.

- Johnson et al. 2002, p. 238.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 18.

- Krisel, Brendan (February 12, 2019). "Preservation Commission Approves 550 Madison Ave Renovation". Midtown-Hell's Kitchen, NY Patch. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Unger 1982b, p. 50.

- Lanson, Gerald (May 1, 1986). "The Att Building In Manhattan". Inc. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Knight 1983, p. 65.

- Unger 1982b, p. 53.

- Unger 1982b, p. 51.

- Horsley, Carter B. (July 12, 1978). "A $75 Million, 41‐Story Prism for I.B.M.". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Tomasson, Robert E. (September 15, 1979). "Quarries Cutting More Granite for Skyline". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Carrol, Maurice (March 31, 1978). "A.T.&T. to Build New Headquarters Tower at Madison and 55th St.: A 'Shift From the Flat Top' City's Involvement Minimal". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Doubliet 1984, p. 72.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 17.

- Langdon, David (January 12, 2019). "AD Classics: AT&T Building / Philip Johnson and John Burgee". ArchDaily. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Unger 1982a, p. 52.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 14.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 494–496.

- Goldberger, Paul (March 31, 1978). "Major, Monument of Post‐Modernism". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, pp. 6–7.

- Knight 1983, p. 64.

- Unger 1982b, p. 52.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 23.

- Dunlap, David W. (September 27, 1992). "Remaking Spaces for Public Use". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Branch 1994, p. 100.

- "550 Madison Ave. will have 30-foot-tall window in new lobby". New York Post. October 21, 2019. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 7.

- Doubliet 1984, p. 73.

- Doubliet 1984, p. 74.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 16.

- Gray, Christopher (March 22, 1998). "Streetscapes/William Van Alen; An Architect Called the 'Ziegfeld of His Profession'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 7, 2017. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Lewis, Hilary (2002). The architecture of Philip Johnson. Boston: Bulfinch Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8212-2788-6. OCLC 50501522.

- Unger 1982b, p. 49.

- Plitt, Amy (October 22, 2019). "550 Madison Avenue's new lobby will be large and light-filled". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- "Gensler Reveals Renderings of the Redesign of Philip Johnson's 550 Madison Avenue in Midtown East". New York YIMBY. October 26, 2019. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- "Tower of Power". V&A Blog. September 3, 2010. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Reynolds, Donald (1994). The Architecture of New York City: Histories and Views of Important Structures, Sites, and Symbols. New York: J. Wiley. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-471-01439-3. OCLC 45730295.

- Minutillo, Josephine (September 30, 2021). "Gensler Renovates Lobby of New York's First Postmodern Skyscraper, 550 Madison Avenue". Architectural Record. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- "At 550 Madison, Alicja Kwade introduces a superheavy object in tension". The Architect’s Newspaper. September 29, 2021. Archived from the original on September 29, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- Angeleti, Gabriella (September 29, 2021). "Alicja Kwade invades corporate New York tower with celestial sculpture". The Art Newspaper. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- Teltsch, Kathleen (August 31, 1981). "Landmark Statue Being Restored". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- Goldberger, Paul (September 28, 1983). "The A.T. & T. Building: Harbinger of a New Era". The New York Times. p. B1. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 122260254.

- Teltsch, Kathleen (August 31, 1981). "Landmark Statue Being Restored". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 27, 2018. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Dewan, Shaila (April 20, 2000). "AT&T Statue to Remain Suburban". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 2, 2019. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Deutsch, Claudia H. (February 21, 1993). "Commercial Property: Sony's New Headquarters; Carving Chippendale Into the Sony Image". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 500.

- "What's happening to the monumental murals at the AT&T building?". The Architect’s Newspaper. November 3, 2017. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Branch 1994, p. 104.

- Dunlap, David W. (May 24, 1994). "So Inviting, So . . . Sony; Can a Public Plaza Be Too Corporate?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Spivack, Caroline (December 4, 2019). "Snøhetta-designed public garden at 550 Madison Avenue secures city approval". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- "Snøhetta gets go ahead for public garden in Phillip Johnson's AT&T building". Dezeen. January 8, 2020. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Gaudino, Linda (May 25, 2022). "New Public Garden Park to Open in Midtown this Fall". NBC New York. Retrieved May 25, 2022.

- Anderson, Susan Heller; Dunlap, David W. (May 28, 1986). "New York Day by Day; Infoquest at A.T.&T". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Leimbach, Dulcie (June 24, 1994). "For Children". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Unger 1982a, p. 47.

- Branch 1994, p. 102.

- "Management: In a cost-cutting era, many CEOs enjoy imperial perks". The Wall Street Journal. March 7, 1995. p. B1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398470391.

- Alexa, Alexandra (January 14, 2020). "See inside the amenity spaces at Philip Johnson's 550 Madison Avenue". 6sqft. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 9.

- Gray, Christopher (April 23, 2000). "Streetscapes/AT&T Headquarters at 195 Broadway; A Bellwether Building Where History Was Made". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 10, 2020. Retrieved February 9, 2020.

- Knight 1983, p. 61.

- Smith, Gene (May 23, 1970). "A.T.&T. Confirms Real Estate Deals On Both Coasts". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Smith, Gene (October 20, 1971). "A.T.&T. Is Planning Rise in Jobs Here". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Unger 1982a, p. 43.

- "A.T &T. Purchases Madison Ave. Site For Possible Office". The New York Times. October 11, 1975. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Unger 1982a, p. 42.

- Unger 1982a, p. 45.

- Knight 1983, p. 62.

- Knight 1983, p. 63.

- Unger 1982a, pp. 45, 47.

- "Notes on People". The New York Times. June 17, 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- "AT&T Sets Architect's Survey". The Wall Street Journal. June 21, 1977. p. 3. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 134192849.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, pp. 13–14.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, pp. 15–16.

- Pogrebin, Robin (August 8, 2010). "The Hand of a Master Architect". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- "Two Towering Votes for New York City". The New York Times. January 28, 1978. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- "AT&T Set to Build New Headquarters In Mid-Manhattan: Granite Structure Would Be 37 Stories Tall; A Source Puts Cost at $60 Million". The Wall Street Journal. March 29, 1978. p. 44. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 134280284.

- "Facility to Cost $110 Million; Plan Is Called a Vote of Confidence in New York". The Wall Street Journal. March 31, 1978. p. 32. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 134280284.

- "IBM Planing N.Y. Tower: Mayor Says City Rebounding". The Washington Post. July 15, 1978. p. D4. ISSN 0190-8286. ProQuest 146929221.

- Carberry, James (June 5, 1978). "Construction Market In New York Shows Signs of Recovering: Numerous Office Buildings, Hotels, Apartments Are in Works, Citibank Aide Says". The Wall Street Journal. p. 20. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 134228514.

- Unger 1982b, p. 48.

- Gottlieb, Martin (May 25, 1984). "A.T.&T. Planning Change in Pact With City for Museum at Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- "3 Proposed Midtown Towers to Get Nearly $30 Million in Abatements". The New York Times. December 20, 1978. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Unger 1982b, pp. 50–51.

- Goldberger, Paul (December 18, 1980). "Critic's Notebook New Madison Avenue Buildings, a New New York?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- Unger 1982b, pp. 52–53.

- Holsendolph, Ernest (January 9, 1982). "U.S. Settles Phone Suit, Drops I.B.M. Case; A.T.& T. To Split Up, Transforming Industry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Henry, Diane (September 29, 1982). "Real Estate; A.T.& T. In Role of Landlord". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Henry, Diane (February 16, 1983). "About Real Estate; A.T.& T. Ends Rent Plan at Its Tax-aided Building". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 13, 2021. Retrieved April 13, 2021.

- "New AT&T welcomed". The Post-Star. January 27, 1984. p. 16. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021 – via newspapers.com.

- Unger, Craig (February 27, 1984). "AT&T Hones Home". New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC. p. 30. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 20.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, p. 499.

- Gottlieb, Martin (July 11, 1984). "A.T.&.T. in a Reversal, to Open Exhibition Space". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Gottlieb, Martin (August 1, 1984). "A.T.& T. Gets Its Tax Break for a Museum". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- "New AT&T Building Gets New York City Tax Break". The Wall Street Journal. August 2, 1984. p. 1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 397915412.

- Scardino, Albert (March 27, 1987). "A.T.&T. Is Vacating Much of Its Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- "AT&T Again Weighs Leasing Out a Portion Of Its Headquarters". The Wall Street Journal. March 30, 1987. p. 1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 39797557.

- Lambert, Bruce (May 20, 1987). "A.T.& T. Signs Pact Limiting Plan to Move". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Fabricant, Florence (June 7, 1987). "The Quilted Giraffe to Move and Reopen in Its Cafe Space". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- "AT&T Seeking to Sublet 80% of Its Headquarters". The Wall Street Journal. January 29, 1991. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398222444.

- Shapiro, Eben (January 28, 1991). "A.T.&T. Is Hoping To Lease Out Space At Its Headquarters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Hylton, Richard D. (May 23, 1991). "Sony Is Reportedly Near Deal To Lease A.T.&T. Skyscraper". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- "AT&T Rents Headquarters In Manhattan to Sony Unit". The Wall Street Journal. July 9, 1991. p. A6. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 135463102.

- Dunlap, David W. (July 28, 1991). "Commercial Property: The Office Market; The Gloom Persists On Offices". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- McKinley, James C. Jr. (August 14, 1991). "CUNY Rescued As City Covers $19 Million Bill". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Dunlap, David W. (January 19, 1992). "A Leaner A.T.&T. Returns to Lower Manhattan". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Barsky, Neil (February 20, 1992). "What Will Become Of Skylines Without Edifice Complexes? --- Big Corporate Ego-Buildings Are a Casualty of the '90s; The New Style: No Style". The Wall Street Journal. p. A1. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398264913.

- Goldberger, Paul (May 24, 1992). "Architecture View; Some Welcome Fiddling With Landmarks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, p. 21.

- Dunlap, David W. (May 1, 1992). "Plan Reduces Public Areas For a Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Landmarks Preservation Commission 2018, pp. 20–21.

- Stern, Fishman & Tilove 2006, pp. 499–500.

- Fabricant, Florence (December 30, 1992). "The Quilted Giraffe Joins the Dinosaurs". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Rothstein, Merv (October 24, 1993). "For the Disabled, Some Progress". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Miller, Bryan (May 24, 1995). "After the Quilted Giraffe, There's Sony and Cyberspace". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Leuchter, Miriam (June 5, 1995). "Sony drafts retail vet to fix problem plaza". Crain's New York Business. Vol. 11, no. 23. p. 15. ProQuest 219181260.

- Ramirez, Anthony (April 21, 1996). "Neighborhood Report: Midtown; Homeless Say Public Plaza Is Harassing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Slatin, Peter (February 22, 1995). "About Real Estate; Sony Looks Across Street for Expansion Space". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Rothstein, Mervyn (April 3, 1996). "Real Estate;Sony makes a number of moves in Manhattan to put more of its businesses under one roof". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Pollack, Andrew (January 24, 1997). "Sony Is Planning to Create A New York Headquarters". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Kinsella, Eileen (December 24, 1997). "Developments: Sony Puts It in Lights: Location, Location". The Wall Street Journal. p. B4. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398596576.

- Magpily, Gerald (April 11, 2002). "DealEstate — April 11, 2002". Daily Deal. Retrieved October 12, 2008.

- "Sony exercises option on 550 Madison Ave". Real Estate Alert. April 10, 2002. p. 1. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- "Sony Said To Be Weighing Manhattan Trophy Office Sale". Real Estate Finance and Investment. February 23, 2004. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on April 16, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021 – via ProQuest.

- "Celebrate Summer at the Newly Renovated Sony Wonder Technology Lab". Sony. July 13, 2009. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Associated Press (February 28, 2010). "Witness: Glass 'everywhere' in NYC atrium collapse". Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved March 15, 2010.

- Schmidt, Michael S. (February 28, 2010). "15 Hurt When Ice Shatters Glass in Sony Building". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Bagli, Charles V. (December 25, 2012). "Future of Corporate Tower May Hinge on a New Use". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Atkinson, Claire (June 13, 2012). "Sony mulls options, including possible sale of HQ". New York Post. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "First-round bids for NYC's Sony Tower due on Monday". Reuters. December 10, 2012. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved April 23, 2013.

- Weiss, Lois (December 12, 2012). "Bids galore for Sony Building". New York Post. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Brown, Eliot (January 18, 2013). "Sony to Sell Tower In $1.1 Billion Deal". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on March 4, 2013. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Bagli, Charles V. (January 19, 2013). "Sony Building to Be Sold for $1.1 Billion". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- "Sony Corporation of America Announces Sale of 550 Madison Avenue Building". Sony Corporation of America. January 17, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 24, 2015.

- Hughes, C. J. (August 13, 2013). "Sony Wants Pizzeria Out of Building in Midtown". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "Chetrit, Bistricer buy said to spell trouble for Sony Building pizzeria". The Real Deal New York. August 14, 2013. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "Sony Building eatery calls it quits after legal tussle". The Real Deal New York. December 30, 2013. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Brown, Eliot (June 9, 2014). "Portion of Sony Building to Become High-End Condos". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Guilbault, Laure (April 11, 2016). "Le Bristol Paris Hotel's Owner to Open in New York". WWD. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Solomont, E.B.; Barger, Kerry (February 19, 2015). "Revealed: Prices, floor plans for all Sony Building condos". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Ungarino, Rebecca (February 19, 2015). "Most expensive New York home—$150 million". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Clarke, Katherine (February 17, 2015). "New York's new most expensive home: Madison Ave. penthouse to hit market for record $150M". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- Grant, Peter (March 27, 2016). "Artist Doesn't Trust Developer to Save Murals at Sony Building". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- "Sony Completes Move of Its NYC Headquarters". Billboard. Archived from the original on May 27, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- "Sony to shutter longtime Madison Avenue store as it moves south". Crain's New York Business. January 10, 2016. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 14, 2021.

- Sender, Henny (April 25, 2016). "New York's 550 Madison Ave sold for $1.3bn". Financial Times. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Bagli, Charles V. (April 29, 2016). "Plan to Turn Sony Building Into Luxury Apartments Is Abandoned". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- Plitt, Amy (June 9, 2016). "Sony Building's $1.4b sale hits public record, making it official". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on June 10, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- Mashayekhi, Rey (June 2, 2016). "Olayan closes on Sony Building buy, gets $570M bridge loan". The Real Deal New York. Archived from the original on June 7, 2016. Retrieved June 10, 2016.

- "Property Watch". The Wall Street Journal. November 20, 2016. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- Chizhik-Goldschmidt, Avital (October 8, 2017). "Is This The Fall Of The Prime Grill Empire?". The Forward. Archived from the original on April 15, 2021. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

- "Snohetta Will Remodel Philip Johnson's AT&T Building". Metropolis. October 30, 2017. Archived from the original on August 4, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- "Snøhetta reimagines Philip Johnson's postmodern New York skyscraper". Dezeen. October 30, 2017. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

- Morris, Keiko (October 29, 2017). "Sony Building Makeover Aims for Upscale Office Tenants". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on April 11, 2021. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- "Protest planned as controversy erupts over AT&T Building". The Architect’s Newspaper. October 1, 2017. Archived from the original on September 24, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- "Architects protest AT&T Building plans with "Hands off my Johnson" placards". Dezeen. November 3, 2017. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- Edelson, Zachary; Fixsen, Anna (November 3, 2017). ""Hands off My Johnson," Say Architects and Preservationists at AT&T Building Redesign Protest". Metropolis. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- "After Protests Over Snøhetta's Proposed Renovation, Philip Johnson's AT&T Building May Get Landmark Status". Architectural Digest. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- Morris, Keiko (November 28, 2017). "Towering Landmark Battle Looms Over Philip Johnson Building". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on August 3, 2018. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- Hudson, Erin (November 9, 2021). "Former AT&T Building May Become Landmark but Interiors Remain Threatened". Architectural Record. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- "Demolition underway at landmark-eligible AT&T Building". The Architect’s Newspaper. January 9, 2018. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- Rosenberg, Zoe (January 9, 2018). "Lobby of Philip Johnson's 550 Madison Avenue is being dismantled". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- Barron, James (January 16, 2018). "This Building Could Be a Landmark. Should Its Lobby Be One, Too?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 17, 2021. Retrieved April 17, 2021.