Supply chain

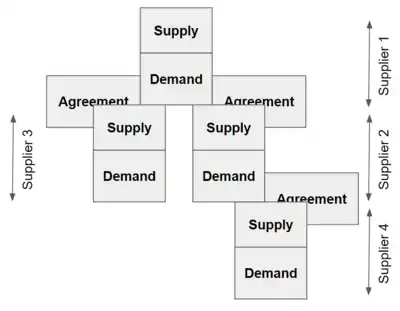

In commerce, a supply chain is a network of facilities that procure raw materials, transform them into intermediate goods and then final products to customers through a distribution system. It refers to the network of organizations, people, activities, information, and resources involved in delivering a product or service to a consumer.[1] Supply chain activities involve the transformation of natural resources, raw materials, and components into a finished product and delivering the same to the end customer.[2] In sophisticated supply chain systems, used products may re-enter the supply chain at any point where residual value is recyclable. Supply chains link value chains.[3] Suppliers in a supply chain are often ranked by "tier", with first-tier suppliers supplying directly to the client, second-tier suppliers supplying to the first tier, and so on.[4]

| Business logistics |

|---|

| Distribution methods |

|

| Management systems |

|

| Industry classification |

|

Overview

.svg.png.webp)

A typical supply chain begins with the ecological, biological, and political regulation of natural resources, followed by the human extraction of raw material, and includes several production links (e.g., component construction, assembly, and merging) before moving on to several layers of storage facilities of ever-decreasing size and increasingly remote geographical locations, and finally reaching the consumer. At the end of the supply chain, materials and finished products only flow there because of the customer behaviour at the end of the chain;[6] academics Alan Harrison and Janet Godsell argue that "supply chain processes should be co-ordinated in order to focus on end customer buying behaviour", and look for "customer responsiveness" as an indicator confirming that materials are able to flow "through a sequence of supply chain processes in order to meet end customer buying behaviour".[7]

Many of the exchanges encountered in the supply chain take place between varied companies that seek to maximize their revenue within their sphere of interest but may have little or no knowledge or interest in the remaining players in the supply chain. More recently, the loosely coupled, self-organizing network of businesses who cooperate in providing product and service offerings has been called the extended enterprise,[8] and the use of the term "chain" and the linear structure it appears to represent have been criticised as "harder to relate ... to the way supply networks really operate.[9] A chain is actually a complex and dynamic supply and demand network.[5]

As part of their efforts to demonstrate ethical practices, many large companies and global brands are integrating codes of conduct and guidelines into their corporate cultures and management systems. Through these, corporations are making demands on their suppliers (facilities, farms, subcontracted services such as cleaning, canteen, security etc.) and verifying, through social audits, that they are complying with the required standard. A lack of transparency in the supply chain can bar consumers from knowledge of where their purchases originated and facilitate socially irresponsible practices. In 2018, the Loyola University Chicago's Supply and Value Chain Center found in a survey that 53% of supply chain professionals considered ethics to be "extremely" important to their organization.[10] Supply-chain managers are under constant scrutiny to secure the best pricing for their resources, which becomes a difficult task when faced with the inherent lack of transparency. Cost benchmarking is one effective method for identifying competitive pricing within the industry. This gives negotiators a solid basis to form their strategy on and drive overall spending down.

Typologies

Marshall L. Fisher (1977) asks the question in a key article, "Which is the right supply chain for your product?"[11] Fisher, and also Naylor, Naim and Berry (1999), identify two matching characteristics of supply chain strategy: a combination of "functional" and "efficient", or a combination of "responsive" and "innovative" (Harrison and Godsell).[7][12]

Brown et al. refer to supply chains as either "loosely coupled" or "tightly coupled":

Cutting-edge companies are swapping their tightly coupled processes for loosely coupled ones, making themselves not only more flexible but also more profitable.[13]

These ideas refer to two polar models of collaboration: tightly coupled, or "hard-wired", also known as "linked", collaboration represents a close relationship between a buyer and supplier within the chain, whereas a loosely-coupled link relates to low interdependency between buyer and seller and therefore greater flexibility.[14] The Chartered Institute of Procurement & Supply's professional guidance suggests that the aim of a tightly coupled relationship is to reduce inventory and avoid stock-outs.[14]

Modeling

There are a variety of supply-chain models, which address both the upstream and downstream elements of supply-chain management (SCM). The SCOR (Supply-Chain Operations Reference) model, developed by a consortium of industry and the non-profit Supply Chain Council (now part of APICS) became the cross-industry de facto standard defining the scope of supply-chain management. SCOR measures total supply-chain performance. It is a process reference model for supply-chain management, spanning from the supplier's supplier to the customer's customer.[15] It includes delivery and order fulfillment performance, production flexibility, warranty and returns processing costs, inventory and asset turns, and other factors in evaluating the overall effective performance of a supply chain.[16]

The supply chain can be split into different segments, after which stage in the supply chain process it considers. The earlier stages of a supply chain, such as raw material processing and manufacturing determine their break-even point by considering production costs, relative to market price. The later stages of a supply chain, such as wholesale and retail determine their break-even point by considering transaction costs, relative to market price. Additionally, there are financial costs associated with all the stages of a supply chain model.

The Global Supply Chain Forum has introduced another supply chain model.[17] This framework is built on eight key business processes that are both cross-functional and cross-firm in nature. Each process is managed by a cross-functional team including representatives from logistics, production, purchasing, finance, marketing, and research and development. While each process interfaces with key customers and suppliers, the processes of customer relationship management and supplier relationship management form the critical linkages in the supply chain.

The American Productivity and Quality Center (APQC) Process Classification Framework (PCF) SM is a high-level, industry-neutral enterprise process model that allows organizations to see their business processes from a cross-industry viewpoint. The PCF was developed by APQC and its member organizations as an open standard to facilitate improvement through process management and benchmarking, regardless of industry, size, or geography. The PCF organizes operating and management processes into 12 enterprise-level categories, including process groups, and over 1,000 processes and associated activities.

In the developing country public health setting, John Snow, Inc. has developed the JSI Framework for Integrated Supply Chain Management in Public Health, which draws from commercial sector best practices to solve problems in public health supply chains.[18]

Mapping

Similarly, supply chain mapping involves documenting information regarding all participants in an organisation's supply chain and assembling the information as a global map of the organisation's supply network.[19]

Management

In the 1980s, the term supply-chain management (SCM) was developed to express the need to integrate the key business processes, from end user through original suppliers.[20] Original suppliers are those that provide products, services, and information that add value for customers and other stakeholders. The basic idea behind SCM is that companies and corporations involve themselves in a supply chain by exchanging information about market demand, distribution capacity and production capabilities. Keith Oliver, a consultant at Booz Allen Hamilton, is credited with the term's invention after using it in an interview for the Financial Times in 1982.[21][22][23] The term was used earlier by Alizamir et al. in 1981.[24]

If all relevant information is accessible to any relevant company, every company in the supply chain has the ability to help optimize the entire supply chain rather than to sub-optimize based on local optimization. This will lead to better-planned overall production and distribution, which can cut costs and give a more attractive final product, leading to better sales and better overall results for the companies involved. This is one form of vertical integration. Yet, it has been shown that the motives for and performance efficacy of vertical integration differ by global region.[25]

Incorporating SCM successfully leads to a new kind of competition on the global market, where competition is no longer of the company-versus-company form but rather takes on a supply-chain-versus-supply-chain form.

The primary objective of SCM is to fulfill customer demands through the most efficient use of resources, including distribution capacity, inventory, and labor. In theory, a supply chain seeks to match demand with supply and do so with minimal inventory. Various aspects of optimizing the supply chain include liaising with suppliers to eliminate bottlenecks; sourcing strategically to strike a balance between lowest material cost and transportation, implementing just-in-time techniques to optimize manufacturing flow; maintaining the right mix and location of factories and warehouses to serve customer markets; and using location allocation, vehicle routing analysis, dynamic programming, and traditional logistics optimization to maximize the efficiency of distribution.

The term "logistics" applies to activities within one company or organization involving product distribution, whereas "supply chain" additionally encompasses manufacturing and procurement, and therefore has a much broader focus as it involves multiple enterprises (including suppliers, manufacturers, and retailers) working together to meet a customer need for a product or service.[26]

Starting in the 1990s, several companies chose to outsource the logistics aspect of supply-chain management by partnering with a third-party logistics provider (3PL). Companies also outsource production to contract manufacturers.[27] Technology companies have risen to meet the demand to help manage these complex systems. Cloud-based SCM technologies are at the forefront of next-generation supply chains due to their impact on optimization of time, resources, and inventory visibility.[28] Cloud technologies facilitate work being processed offline from a mobile app which solves the common issue of inventory residing in areas with no online coverage or connectivity.[29]

Resilience

Supply chain resilience is "the capacity of a supply chain to persist, adapt, or transform in the face of change".[30] For a long time, the interpretation of resilience in the sense of engineering resilience (= robustness[31]) prevailed in supply chain management, leading to the notion of persistence.[30] A popular implementation of this idea is given by measuring the time-to-survive and the time-to-recover of the supply chain, allowing identification of weak points in the system.[32] More recently, the interpretations of resilience in the sense of ecological resilience and social–ecological resilience have led to the notions of adaptation and transformation, respectively.[30] A supply chain is thus interpreted as a social-ecological system that – similar to an ecosystem (e.g. forest) – is able to constantly adapt to external environmental conditions and – through the presence of social actors and their ability to foresight – also to transform itself into a fundamentally new system.[33] This leads to a panarchical interpretation of a supply chain, embedding it into a system of systems, allowing to analyze the interactions of the supply chain with systems that operate at other levels (e.g. society, political economy, planet Earth).[33] For example, these three components of resilience can be discussed for the 2021 Suez Canal obstruction, when a ship blocked the canal for several days.[34] Persistence means to "bounce back"; in our example it is about removing the ship as quickly as possible to allow "normal" operations. Adaptation means to accept that the system has reached to a "new normal" state and to act accordingly; here, this can be implemented by redirecting ships around the African cape or use alternative modes of transport. Finally, transformation means to question the assumptions of globalization, outsourcing, and linear supply chains and to envision alternatives; in this example this could lead to local and circular supply chains.

Role of the internet

On the internet, customers can directly contact the distributors. This has reduced the length of the chain to some extent by cutting down on middlemen. Some of the benefits are cost reduction and greater collaboration.[35] Social media now plays an important role in holding corporations accountable due to rapid spread of information that can sway purchasing decisions.[10] Internet has allowed all types of transactions (economic and social) to be performed online, which in turn has enabled real-time digital capture of data; the use of big data analytics to drive supply chains has been reviewed in recent papers by Sanders and others.[36][37]

Social responsibility

Incidents like the 2013 Savar building collapse with more than 1,100 victims have led to widespread discussions about corporate social responsibility across global supply chains. Wieland and Handfield (2013) suggest that companies need to audit products and suppliers and that supplier auditing needs to go beyond direct relationships with first-tier suppliers (those who supply the main customer directly). They also demonstrate that visibility needs to be improved if the supply cannot be directly controlled and that smart and electronic technologies play a key role to improve visibility. Finally, they highlight that collaboration with local partners, across the industry and with universities is crucial to successfully manage social responsibility in supply chains.[38] This incident also highlights the need to improve workers safety standards in organizations. Hoi and Lin (2012) note that corporate social responsibility can influence the enacting of policies that can improve occupational safety and health management in organizations. In fact, international organizations with presence in other nations have a responsibility to ensure that workers are well protected by policies in an organization to avoid safety related incidents.[39]

Food supply chains

Many agribusinesses and food processors source raw materials from smallholder farmers. This is particularly true in certain sectors, such as coffee, cocoa and sugar. Over the past 20 years, there has been a shift towards more traceable supply chains. Rather than purchasing crops that have passed through several layers of collectors, firms are now sourcing directly from farmers or trusted aggregators. The drivers for this change include concerns about food safety, child labor and environmental sustainability as well as a desire to increase productivity and improve crop quality.[40]

In October 2009, the European Commission issued a Communication concerning "a better functioning food supply chain in Europe", addressing the three sectors of the European economy which comprise the food supply chain: agriculture, food processing industries, and the distribution sectors.[41] An earlier interim report on food prices (published in December 2008) had already raised concerns about the food supply chain.[41] Arising out of the two reports, the Commission established a "European Food Prices Monitoring Tool", an initiative developed by Eurostat and intended to "increase transparency in the food supply chain".[42]

In March 2022 the Commission noted "the need for EU agriculture and food supply chains to become more resilient and sustainable".[43]

Regulation

Supply chain security has become particularly important in recent years. As a result, supply chains are often subject to global and local regulations. In the United States, several major regulations emerged in 2010 that have had a lasting impact on how global supply chains operate. These new regulations include the Importer Security Filing (ISF)[44] and additional provisions of the Certified Cargo Screening Program.[45] EU's draft supply chain law are due diligence requirements to protect human rights and the environment in the supply chain. [46]

Development and design

With the increasing globalization and easier access to different kinds of alternative products in today's markets, the importance of product design to generating demand is more significant than ever. In addition, as supply, and therefore competition, among companies for the limited market demand increases and as pricing and other marketing elements become less distinguishing factors, product design likewise plays a different role by providing attractive features to generate demand. In this context, demand generation is used to define how attractive a product design is in terms of creating demand. In other words, it is the ability of a product's design to generate demand by satisfying customer expectations. But product design affects not only demand generation but also manufacturing processes, cost, quality, and lead time. The product design affects the associated supply chain and its requirements directly, including manufacturing, transportation, quality, quantity, production schedule, material selection, production technologies, production policies, regulations, and laws. Broadly, the success of the supply chain depends on the product design and the capabilities of the supply chain, but the reverse is also true: the success of the product depends on the supply chain that produces it.

Since the product design dictates multiple requirements on the supply chain, as mentioned previously, then once a product design is completed, it drives the structure of the supply chain, limiting the flexibility of engineers to generate and evaluate different (and potentially more cost-effective) supply-chain alternatives.[47]

See also

- Supply-chain sustainability

- Digital Supply Chain

- Software supply chain

- Freight forwarder

- Logistics

- Supply chain attack

- 2021 global supply chain crisis

References

- Hayes, Adam. "Supply Chain". Investopedia. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- Kozlenkova, Irina; et al. (2015). "The Role of Marketing Channels in Supply Chain Management". Journal of Retailing. 91 (4): 586–609. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2015.03.003. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- Nagurney, Anna (2006). Supply Chain Network Economics: Dynamics of Prices, Flows, and Profits. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. ISBN 978-1-84542-916-4.

- SCM Portal, Supplier Tiering, Procurement Glossary supplied by CIPS, accessed 11 July 2021

- cf. Wieland, Andreas; Wallenburg, Carl Marcus (2011). Supply-Chain-Management in stürmischen Zeiten (in German). Berlin: Universitätsverlag der TU. ISBN 978-3-7983-2304-9.

- Gattorna, J. L., ed. (1998), Strategic Supply Chain Alignment, Gower, Aldershot

- Harrison, A. and Godsell, J. (2003), Responsive Supply Chains: An Exploratory Study of Performance Management, Cranfield School of Management, accessed 12 May 2021

- Ross, Jeanne W. (2006). Enterprise architecture as strategy: creating a foundation for business execution. Weill, Peter, Robertson, David, 1935-. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Business School Press. ISBN 1-59139-839-8. OCLC 66463473.

- Keith, R., So Why Do We Call it a 'Supply Chain' Anyway?, Industry Week, emphasis added, published 3 December 2012, accessed 6 January 2021

- "In this issue of SCMR: The ethical supply chain". www.scmr.com. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- Fisher, M. L., What is the Right Supply Chain for your Product?, Harvard Business Review, March–April 1977, pp 105-116

- Naylor, B. J. et al., Leagility: Integrating the lean and agile manufacturing paradigms in the total supply chain, International Journal of Production Economics, vol 19, no. 8, pp 765-784

- Brown, J. S., Hagel, J. III and Durchslag, S. (2002), Loosening up: How process networks unlock the power of specialization, McKinsey Quarterly, vol 2 ,pp 59-69

- CIPS, Loosely-Coupled vs Tightly-Coupled Supply Chain, no date, accessed 13 May 2021

- "Supply Chain Council, SCOR Model".

- Stevens, Graham C. (1989). "Integrating the Supply Chain". International Journal of Physical Distribution & Materials Management. Emerald Insight. 19 (8): 3–8. doi:10.1108/EUM0000000000329. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- "SCM Institute". scm-institute.org. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- "Getting Products to People: The JSI Framework for Integrated Supply Chain Management in Public Health".

- American Express, What is Supply Chain Mapping and Why is it Important?, published 4 February 2022, accessed 11 June 2022

- Oliver, R. K.; Webber, M. D. (1992) [1982]. "Supply-chain management: logistics catches up with strategy". In Christopher, M. (ed.). Logistics: The Strategic Issues. London: Chapman Hall. pp. 63–75. ISBN 978-0-412-41550-0.

- Jacoby, David (2009). Guide to Supply Chain Management: How Getting it Right Boosts Corporate Performance. The Economist Books (1st ed.). Bloomberg Press. ISBN 978-1-57660-345-1.

- Andrew Feller, Dan Shunk, & Tom Callarman (2006). BPTrends, March 2006 - Value Chains Vs. Supply Chains

- Blanchard, David (2010). Supply Chain Management Best Practices (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-53188-4.

- Alizamir, S., Alptekinoglu, A., & Sapra, A. (1981). Demand management using responsive pricing and product variety in the presence of supply chain disruptions: Working paper, SMU Cox School of Business.

- Durach, Christian F.; Wiengarten, Frank (2019-10-31). "Supply chain integration and national collectivism". International Journal of Production Economics. 224: 107543. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.107543. ISSN 0925-5273. S2CID 211460516.

- "eShipGlobal - Ship. Connect. Deliver". eShipGlobal. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- Selecting a Third Party Logistics (3PL) Provider Martin Murray, about.com

- "JD.com: Building the Smart Logistic System for the Future". Technology and Operations Management. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- Inventory®, Cloud (2021-01-14). "IS YOUR SUPPLY CHAIN PREPARED FOR DISRUPTION? — #1 Cloud Inventory® Software as a Service". Medium. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- Wieland, Andreas; Durach, Christian F. (2021). "Two perspectives on supply chain resilience". Journal of Business Logistics. 42 (3): 315–322. doi:10.1111/jbl.12271. ISSN 2158-1592. S2CID 233812114.

- Durach, Christian F.; Wieland, Andreas; Machuca, Jose A. D. (2015). "Antecedents and dimensions of supply chain robustness: a systematic literature review" (PDF). International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. 45: 118–137. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-05-2013-0133. hdl:10398/9123. ISSN 0960-0035.

- Simchi‐Levi, D., Wang, H., & Wei, Y. (2018). Increasing supply chain robustness through process flexibility and inventory. Production and Operations Management, 27(8), 1476-1491.

- Wieland, Andreas (2021). "Two perspectives on supply chain resilience". Journal of Supply Chain Management. 57 (1). doi:10.1111/jscm.12248. ISSN 1745-493X.

- "Ships Get Moving Through Suez as Giant Ever Given Is Freed". www.supplychainbrain.com. Retrieved 2021-04-03.

- "What Is the Role of the Internet in Supply-Chain Management in B2B?". Retrieved 2017-08-24.

- Sanders, Nada R. (2016-05-01). "How to Use Big Data to Drive Your Supply Chain". California Management Review. 58 (3): 26–48. doi:10.1525/cmr.2016.58.3.26. ISSN 0008-1256. S2CID 156591110.

- Hofmann, Erik; Rutschmann, Emanuel (2018-05-14). "Big data analytics and demand forecasting in supply chains: a conceptual analysis". The International Journal of Logistics Management. 29 (2): 739–766. doi:10.1108/IJLM-04-2017-0088. ISSN 0957-4093.

- Wieland, Andreas; Handfield, Robert B. (2013). "The Socially Responsible Supply Chain: An Imperative for Global Corporations". Supply Chain Management Review. 17 (5).

- "Corporate social responsibility", Preventing Corporate Accidents (0 ed.), Routledge, pp. 252–279, 2012-06-25, doi:10.4324/9780080570297-17, ISBN 978-0-08-057029-7, retrieved 2022-04-21

- International Finance Corporation (2013), Working with Smallholders: A Handbook for Firms Building Sustainable Supply Chains (online).

- European Commission, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A better functioning food supply chain in Europe, provisional version published 28 October 2019, accessed 26 April 2022

- European Commission, European Food Prices Monitoring Tool, accessed 16 June 2022

- European Commission, Commission acts for global food security and for supporting EU farmers and consumers, published 23 March 2022, accessed 26 April 2022

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-22. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "TSA: Certified Cargo Screening Program". Archived from the original on 2011-06-16. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- "The EU's new supply chain law – what you should know". Retrieved 2021-07-28.

- Gokhan, Nuri Mehmet; Needy, Norman (December 2010). "Development of a Simultaneous Design for Supply Chain Process for the Optimization of the Product Design and Supply Chain Configuration Problem" (PDF). Engineering Management Journal. 22 (4): 20–30. doi:10.1080/10429247.2010.11431876. S2CID 109412871.