TAZARA Railway

The Tazara Railway, also called the Uhuru Railway or the Tanzam Railway, is a railway in East Africa linking the port of Dar es Salaam in east Tanzania with the town of Kapiri Mposhi in Zambia's Central Province. The single-track railway is 1,860 km (1,160 mi) long and is operated by the Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA).

| Tanzania–Zambia Railway | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Status | Minimally operational |

| Termini |

|

| Website | www |

| Service | |

| Type | Heavy rail |

| Operator(s) | Tanzania–Zambia Railway Authority |

| History | |

| Opened | 1975 |

| Technical | |

| Line length | 1,860 km (1,160 mi) |

| Track gauge | 1,067 mm (3 ft 6 in) |

(interactive version)

1000mm gauge, 1067mm gauge (TAZARA)

Tanzania-Zambia Railway (TAZARA) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The governments of Tanzania, Zambia, and the People's Republic of China built the railway to eliminate landlocked Zambia's economic dependence on Rhodesia and South Africa, both of which were ruled by white-minority governments.[1] The railway provided the only route for bulk trade from Zambia's Copperbelt to reach the sea without having to transit white-ruled territories. The spirit of Pan-African socialism among the leaders of Tanzania and Zambia and the symbolism of China's support for newly independent African countries gave rise to Tazara's designation as the "Great Uhuru Railway", Uhuru being the Swahili word for freedom.

The project was built from 1970 to 1975 as a turnkey project financed and supported by China. At its completion, the TAZARA was the longest railway in sub-Saharan Africa.[2] TAZARA was also the largest single foreign-aid project undertaken by China at the time, at a construction cost of US $406 million (the equivalent of US $2.83 billion today).[3][4]

TAZARA has faced operational difficulties from the start and was kept running by continued assistance from China, several European countries, and the United States. Freight traffic peaked at 1.2 million tons in 1986, but began to decline in the 1990s as the end of apartheid in South Africa and the independence of Namibia opened alternative transport routes for Zambian copper. Freight traffic bottomed out at 88,000 metric tons in Fiscal Year (FY) 2014/2015, less than 2% of the railway's design capacity of 5 million tonnes per year.[5][6]

Route

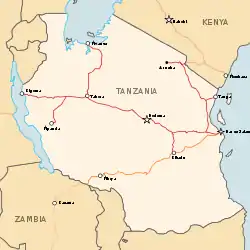

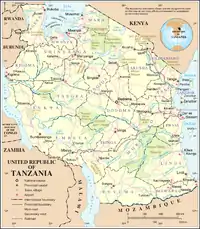

Running some 1,860 km (1,160 mi) from Tanzania's largest city, Dar es Salaam, on the coast of the Indian Ocean to Kapiri Mposhi, near the Copperbelt of central Zambia, the Tazara is sometimes regarded as the greatest engineering effort of its kind since World War II. The railway crosses Tanzania in a southwest direction, leaving the coastal strip and then entering largely uninhabited areas of the vast Selous Game Reserve. The line crosses the Tanzam Highway at Makambako and runs parallel to the highway toward Mbeya and the Zambian border, before entering Zambia, and linking with Zambia Railways at Kapiri Mposhi.

From sea level, the railway climbs to 550 metres (1,800 feet) at Mlimba, and then reaches its highest point of 1,789.43 m (5,870 ft 10 in) at Uyole in Mbeya before descending to 1,660 m (5,450 ft) at Mwenzo, the highest point in Zambia, and settling to 1,274.63 m (4,181 ft 10 in) at Kapiri Mposhi.[7]

The Tanzanian interior

Upon leaving the coast, Tazara runs west, through the Pwani Region, then dips south of Mikumi National Park and enters the wilderness in the northern part of the Selous Game Reserve in the Morogoro Region. The Selous is one of the largest faunal reserves in the world and passengers can often see wildlife such as giraffe, elephant, zebra, antelope and warthog, which have become accustomed to the rumbling of the trains.[8] The railway crosses the Great Ruaha River for the first time in the Selous.

Further south, the railway cuts through the fertile Kilombero Valley, and skirts the great Kibasira Swamp. The next section, between Mlimba (the Kingdom of Elephants) and Makambako (the Place of Bulls) was to be 158 km (98 mi) long, and presented the builders of the railway with the greatest challenge. To lay track across rugged mountains, precipitous valleys and deep swamps, it was necessary to construct 46 bridges, 18 tunnels, and 36 culverts.[9] Because of the heavy rainfall in this area, intricate drainage works had to be integrated with every feature. The most spectacular feature is the bridge across the Mpanga River, which stands on three 50 m (164 ft) tall pillars.

At Kidatu, a metre gauge branch railway connects to the Central Line at Kilosa. The TAZARA then climbs into the Southern Highlands of the Iringa Region and levels out onto a rolling plateau. Here, in the coffee and tea country of the Njombe Region, the weather becomes noticeably cooler, the air sharper. On the approach to Makambako, the Udzungwa Mountains National Park rise 2,137 m (7,011 ft) to the north, while the Kipengere Range roll ahead to the south. Makambako is one of the meeting points of the railway and the Tanzania-Zambia Highway.

From Makambako the railway and the highway run a parallel course towards Mbeya running past the Kipengere Range that towers to the south. Here in the Mbeya Region, the Tazara crosses several upstream tributaries of the Great Ruaha, which are lined with belts of forest and grasslands.

After the Kipengere Mountains, the Uporoto Range takes over with the Usangu Flats stretching to the north. From Mbeya town, both the railway and the highway heads northwest to Tunduma where they cross the border into Zambia.

Zambia

The Tazara enters northeastern Zambia in the Nakonde District, in the Muchinga Province, and heads southwest to Kasama. It then turns due south and crosses the Chambeshi River en route to Mpika. After entering the Central Province, the railway again turns to the southwest, running along the northern foothills of the Muchinga Mountains, past Serenje and Mkushi to Kapiri Mposhi, located due north of the Lusaka.

Passenger service

As of February 2016, two passenger trains per week traverse the entire TAZARA in each direction. Departures are on Tuesdays and Fridays in each direction. The brand new Express train travels Fridays from Dar and Tuesdays from New Kapiri Mposhi. The Ordinary train makes all possible stops, and the Express service makes fewer stops[8][10] The entire journey, as scheduled, takes 36 hours, though delays can extend the trip to as long as 50 hours or more.[8][3] Trains on the TAZARA are slower than overland bus service but cheaper and safer.[11][8] The TAZARA trains have attracted foreign tourists wishing to see the landscape and wildlife along route.[8]

Rovos Rail of South Africa operates the Pride of Africa, a luxury train, that runs periodic tours from Cape Town to Dar es Salaam via the TAZARA.[12]

The TAZARA tracks are also used for passenger commuter rail service between Dar es Salaam and its suburbs. The Dar es Salaam commuter rail was launched in 2012 to relieve traffic congestion. The TAZARA offers two routes on its 20.5 km rail network.[13]

Rail gauge and standards

The TAZARA has a track gauge of 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm), also known as the Cape gauge, which is widely used throughout southern Africa.[14] TAZARA connects to the Cape-gauge Zambia Railways at Kapiri Mposhi. The remainder of Tanzania’s railways have 1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in) metre gauge tracks.[15] A transshipment station with a break of gauge station was built in Kidatu in 1998.[15]

Except for the rail gauge, TAZARA generally reflects Chinese railway standards of the 1970s. The technical characteristics of the line were:

- Couplers: Janney (AAR)[16]

- Brakes: Air/vacuum[17]

- Axle loading: 20 metric tons[17]

- Sleepers: Concrete on main line, Wood at turnouts and on bridges[17]

- Rail: High-manganese steel, 45 kg/m (90 lb/yard), mostly jointed[18]

- Signals: Semaphore

- Design speed: 110 km/h (70 mph)[19]

- Design capacity: 5 million metric tons per year[5]

- Loading gauge: Limited by 22 tunnels in the Udzungwa Mountains

Equipment

Locomotives

At the moment the railways operates three types of locomotives as listed below:

| Type | Quantity | Manufacturer | Notes | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SDD20 | 10 | CSR Qishuyan | [20][21] | |

| U30C | 10 | Krupp | Variant of GE U26C, not to be confused with the identically-named GE U30C. | [21] |

| CK6 | CSR Chengdu | Shunting locomotive | [22] | |

History

Origins of the project

In the late 19th century, Cecil Rhodes envisioned a railway from British Rhodesia to Tanganyika (then German East Africa) to carry copper ore.[2] After World War I, Tanganyika was handed over to the United Kingdom for administration as a League of Nations Mandate, and British colonial authorities again explored the idea.[2] Still, from the outset, the Western powers refused to construct the Tanzam railway because it would have been unprofitable for Western investors.[23]

Following World War II, interest in railway construction revived.[2] A map from April 1949 in Railway Gazette showed a proposed line from Dar es Salaam to Kapiri Mposhi, not far from the route that would eventually be taken by the Chinese railway.[24] A report in 1952 by Sir Alexander Gibb & Partners concluded that the Northern Rhodesia-Tanganyika railway was not economically justified, due to the low level of agricultural development and the fact that existing railways through Mozambique and Angola were adequate for carrying copper exports.[25] A World Bank report in 1964 projected that only 87,000 tons of cargo would be carried between Zambia and Tanzania by the year 2000, not enough to support a railway, and recommended that a road be built instead.[26]: 43

In 1961, Tanganyika became independent under the leadership of Julius Nyerere, and in 1964 the country joined with Zanzibar to form the United Republic of Tanzania. Also in 1964, Northern Rhodesia was granted independence as Zambia, under the leadership of Kenneth Kaunda. Both Nyerere and Kaunda were charismatic socialist African leaders who supported the self-determination of their African neighbors.[2] A railway connecting their two countries would help to develop the agricultural regions of southwestern Tanzania and northeastern Zambia.[27]

Attempts to secure funding

Nyerere and Kaunda pursued different avenues for the construction of a rail route. When Nyerere visited Beijing in February 1965, he was hesitant to raise the issue of the railway out of concern that China was also a poor country. President Liu Shaoqi offered to assist Tanzania and Zambia in building a railway between the two countries.[3][28] Chairman Mao Zedong told Nyerere, "You have difficulties as do we, but our difficulties are different. To help you build the railway, we are willing to forsake building railways for ourselves."[3] Chinese leaders assured Nyerere that Tanzania and Zambia would have full ownership of the completed railway, along with transferred technology and equipment.[28] Nyerere did not immediately accept the Chinese offer but sought to use it to induce Western backing for the railway, but none was forthcoming.[29] He did, however, accept a team of Chinese surveyors, who produced a short report in October 1966.

Kaunda was wary of Communist involvement and wanted to maintain friendly ties with Britain. He turned down an offer from the Chinese Embassy in Lusaka to build the railway. In addition, Zambia and Rhodesia were joint owners of the Zambian Railway, and the joint ownership agreement would penalize Zambia for diverting traffic to other railways. A Canadian-British aerial survey was commissioned and conducted by chief engineer John Leslie Charles,[30] concluding in a July 1966 report that the line was "feasible and economic" based on a predicted 2.5 million tons of traffic, with an estimated construction cost of £126 million ($353 million). Western funding was not, however, forthcoming,[31] as Britain, Japan, West Germany, World Bank, the United States and United Nations all declined to fund the project.[2][32] The Soviet Union was also uninterested.[32]

Chinese support

At the time, China was actively seeking diplomatic support in the Third World against the United States and Soviet Union. Trade Minister Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu and other ministers from Zanzibar were instrumental in lobbying Chinese leaders for support and then persuading Nyerere to accept the assistance.[33] British prime minister Harold Wilson, after seeing Tanzania's pro-China attitude at the 1965 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference, claimed that many of Nyerere's ministers were "directly in the Chinese pay."[34] Canadian prime minister Lester Pearson also questioned whether Nyerere should get so close to the Chinese.[35]

Nyerere later complained that Western nations opposed the Chinese plans for the railway, but did not offer him any alternative.[36]

"... all the money in this world is either Red or Blue. I do not have my own Green money, so where can I get some from? I am not taking a cold war position. All I want is money to build it."

— Julius Nyerere, PRO, DO183/730, from Dar es Salaam to CRO, No. 1089, 3 July 1965

In November 1965, Southern Rhodesia's white-led colonial government issued its Unilateral Declaration of Independence from Britain, threatening Zambia's access to the sea. In the first months after UDI, supplies had to be airlifted to Zambia or transported 1,600 km (1,000 mi) by road.[37] Nyerere warned Humphry John Berkeley, a British politician who served as the economic consultant for the Canadian-British survey team, that "The West must hurry, because the Chinese are going ahead." Yet, when Berkeley met with Harold Wilson, the British prime minister assured him that "The Chinese have not got the money to build the railway."[38]

Finally, Kaunda dropped his objections and accepted the Chinese offer while visiting China in January 1967.[39][40] On 6 September 1967, an agreement was signed in Beijing by the three nations. China committed itself to building a railway between Tanzania and Zambia, supplying an interest-free loan of RMB988 million (approx. US$406 million) to be repaid between 1973 and 2013.[3][4]

The West reacted to Chinese backing for the project with both derision and alarm. Critics questioned the construction quality and competence of the Chinese, calling the TAZARA the "bamboo railway".[32] The Wall Street Journal stated in 1967, "the prospects of hundreds and perhaps thousands of Red Guards descending upon an already troubled Africa is a chilling one for the West."[41] The United States funded the Tanzam Highway, which was built from 1968 to 1973, to compete with the railway.[42] As the projects proceeded in parallel, Chinese and American workers clashed at the Great Ruaha River bridge in 1970.[43]

Construction

Before the railway construction began, 12 Chinese surveyors traveled for nine months on foot from Dar es Salaam to Mbeya in the Southern Highlands to choose and align the railway's path. Chinese workers had already begun arriving in 1969, and construction began in July 1970.[4] A formal inauguration ceremony was held on 26 October 1970, where the band played Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman and marchers held signs saying, "The Uhuru line will fight Imperialism".[44]

Chinese assistance was provided in large part by the Railway Engineering Corps of the People’s Liberation Army (predecessor of China Railway Construction Corporation) and the foreign aid department of the Ministry of Railways (predecessor of China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation).[45] Chinese personnel sent to Africa were selected for political dependability, moral probity, technical expertise and personal fitness, and underwent as long as two months of training.[46] Chinese assistance followed the country's socialist ethos, a labor-intensive model instead of the Western capital-intensive model.[47]

In total, China sent about 50,000 personnel to work on the railway from 1965 to 1976, including 30,000 to 40,000 workers.[48] An estimated 60,000 Africans participated in the railway's construction.[48] At the height of construction in 1972, there were 13,500 Chinese and 38,000 African workers on the project.[49] Chinese engineers lived and worked according to the same standards as their African counterparts.[2][47] Construction camps were set up for each 64-kilometre (40 mi) section of track, being relocated as the work progressed. Papaya and banana trees were grown to provide shade and food, and workers tended vegetable gardens in the camps in off-hours.[50]

The work involved moving 330,000 tons of rail and 89 million cubic meters of earth and rock, and the construction of 93 stations, 320 bridges, 22 tunnels and 2,225 culverts.[46][51] Virtually all building materials, equipment and significant amounts of food and medical supplies were shipped from China.[46] Braving rain, sun and wind, the workers laid the track through some of Africa's wildest and most rugged landscapes. One Chinese worker recalled that his team was trapped in the wilderness for a week after floods and landslides washed away the only connecting road.[46] "We lived in fear of lions and hyenas."[46] Over 160 workers, including 64 Chinese nationals, died in construction accidents.[51]

The section from Mlimba to Makambako crosses mountains and steep valleys. Almost 30 percent of the bridges, tunnels, viaducts, and earthworks of the entire route are located a 16-kilometre (10 mi) stretch of this section. The bridge across the Mpanga River is 49 metres (160 ft) in height, and the Irangi Number 3 Tunnel is 2.4 km (1+1⁄2 mi) long. After the work crews reached Zambia at the end of 1972, the terrain became much easier, and the track-laying machine could advance 3 km (2 mi) per day[52]

The project pressed forward despite the enormous upheaval in China caused by the Cultural Revolution, during which most domestic railway projects were delayed as many government officials were purged. President Liu Shaoqi, who had made the offer to President Nyerere in 1965, was removed from power in 1966, publicly vilified and died in 1969. In Tanzania, Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu, who had persuaded the Chinese to back the TAZARA, was sentenced to death in 1972 for allegedly plotting to overthrow the Zanzibar government. He was pardoned by Nyerere in 1978.

The first passenger train arrived in Dar es Salaam on 24 October 1975,[53] the 11th anniversary of Zambia's independence from Great Britain.

Initial difficulties

The TAZARA has been a major economic conduit in the region notwithstanding operating difficulties from the start and never reaching its design capacity of 5 million metric tons. In the first two years of operation, TAZARA carried over 1.1 million metric tons of cargo annually. The diesel hydraulic locomotives sent by the Chinese were insufficiently powerful to haul heavy loads up the steep escarpment between Mlimba and Makambako, limiting the line's carrying capacity.[32] When the Chinese rolling stock broke down, there was limited local capacity for repair.[32] By 1978, 19 to 27 of the locomotives were out of operation, as were half of the rail cars.[54]

The railway was also beset with staff difficulties. In their haste to complete the railway, the Chinese did not train enough African technicians to take over management of the railway.[32] In 1972, two hundred Tanzanian and Zambian students were enrolled in the Northern Jiaotong University in Beijing to learn railway management, but a dozen of them were expelled in the first year for misbehavior.[26]: 99 Employee theft was so common that 20 Zambian crew members were fired in 1978 for stealing, drivers were brought back from China for a return run, and hundreds of other Chinese advisers had their stay extended.[54] These problems resulted in much lengthier than planned turnaround times for freight, and in 1978 Zambia had to break ranks and reopen links with white-ruled Rhodesia for its copper exports.[55]

TAZARA played an important role in the black nationalist struggles of the late 1970s and 1980s. The railway served as a trade route for Zambia, Zimbabwe, and Malawi that did not pass through apartheid South Africa, or Angola or Mozambique, which were embroiled in civil wars with South African-backed proxies.[19] During Zimbabwe's struggle for independence, the white Rhodesian government targeted ZIPRA's supply lines from Tanzania.[56] Rhodesian forces also attacked and destroyed three bridges; the Chambeshi River Bridge was blown up by the Selous Scouts in 1979 and required one year to reconstruct.[57][19] As a result of these difficulties, cargo transport fell below 800,000 tons per annum from 1979/80 to 1982/83. In addition, landslides and washouts frequently disrupted service, especially during the rainy seasons of 1979 and 1985/86.[32][57]

Foreign support in the 1980s

In 1983, Tanzania and Zambia invited the Chinese back to help manage the railway.[58] About 250 Chinese managers were assigned to railway bureaus along the route.[58] They brought operational profitability to the railway and paid for their expenses through revenues, but China had to issue additional zero-interest loans to pay for spare parts and rehabilitation.[58] From 1987 to 1993, foreign aid totaling $150 million was supplied by the European Economic Community, Austria, Denmark, Finland, France, West Germany, Norway, Sweden, and Switzerland.[59]

In 1987, the United States also joined in the donor efforts to improve the TAZARA and reduce the dependency of "frontline states" on South Africa.[60][57][61] A 1987 report commissioned for the USAID identified inadequate motive power and poor equipment maintenance as constraints to operational capacity.[60] The report found TAZARA mechanics to be poorly trained and supervised, many being illiterate, and faced with the need to maintain a diverse set of equipment from different donor countries.[60] The USAID then funded a $50 million program over seven years, providing locomotives, facilities, and training.[57] Equipment repairs would only "reduce some short-range problems", and the report highlighted the need to address "underlying causes", such as the locomotive workshops lacking basic supplies, and less than 20% of employees at the locomotive workshops being engaged in actual work.[60]

Thanks to support from foreign donors, the cargo transported annually by TAZARA increased from 1.0 to 1.9 million metric tons in 1986 to 1991. The locomotive availability rate rose from 46% to 65%, and wagon turnaround time was reduced from 35 days to 20 days.[57] Passenger traffic on the railway rebounded from 564,000 in the FY1982/83 to 1.6 million in FY1990/91.[57][19][32] Local goods accounted for nearly half of the cargo shipped on the line between 1985 and 1988.[32]

Decline

along the TAZARA

In the 1990s, the economic performance of the railway began to decline with changes to the broader economic and political environment. With the independence of Namibia in 1990 and multiracial elections in South Africa in 1994, southern Africa was no longer dominated by white minority governments, and Zambian copper had more economic outlets to the south and east. Road transport provided competition in the form of the Trans–Caprivi Highway and the Walvis Bay Corridor to Namibia.

The privatization of Zambia's copper mines forced railways in Zambia to compete for previously-guaranteed government cargo.[62] Traffic on Zambian Railways fell from 6 million tonnes in 1975 to 690,000 tonnes in 2009. TAZARA suffered an even greater drop in traffic.

In the early 2000s, the end of civil wars in Angola and Mozambique opened further rail outlets for Zambian copper.[63][64] In 2008, the railway's condition was described as being "on the verge of collapse due to financial crisis," and dangerous track conditions were discovered by Chinese technicians inspecting the line.[65] The company's cash flow difficulties have led to delays in paying salaries, resulting in frequent strikes by the workforce.[66] By 2012, TAZARA had only 10 operational main line locomotives.[67] In September 2013, the TAZARA was reporting $1.53 million in monthly revenue against $2.5 million in monthly expenditures.[11]

Attempts at revitalization

The railway is sometimes described as an economic "lifeline" for Zambia and the government in Lusaka has ostensibly remained committed to its revitalization.[11] In April 2013, Zambia’s second largest copper miner, Konkola Copper Mines, agreed to re-commence shipping copper on the TAZARA after a five-year hiatus.[68] By November 2013, the line was reportedly shipping 15,000 tons of copper weekly, but still prone to breakdowns and delays.[68] In addition to carrying copper, manganese, cobalt and other minerals for export, the TAZARA also transports Asian imports and fertilizer to Zambia, Congo, Malawi, Burundi, and Rwanda.[11]

The Chinese government has also been unwilling to see the complete shutdown of its signature foreign aid project. In 2011, China cancelled half of the debts it was owed by the TAZARA.[11] Since the loan was interest-free and not indexed for inflation, the real value of the debt had also shrunk by more than 80%.[lower-alpha 1]

Additional Chinese aid has kept TAZARA in a state of minimal operation. In 2010, the Chinese government gave TAZARA a US$39 million interest-free loan,[69][70] but TAZARA management estimated that it would require US$770 million to become commercially viable.[71] In 2012, the Chinese government gave another $42 million for equipment and training.[67] In March 2014, Tanzanian, Zambian and Chinese officials held talks to recapitalize the TAZARA and to split it into a Tanzanian company and a Zambian company.[72] The Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority took delivery in 2015 of four diesel-electric locomotives and 18 coaches from China. TAZARA’s Dar es Salaam workshop has also begun a programme to refurbish 24 out-of-use coaches.[73]

In FY2014/15, freight traffic fell to 88,000 metric tons in Fiscal Year (FY) but rebounded to 130,000 tons in FY2015/16.[74]

In 2018, TAZARA and South African firm Calabash Freight reached an agreement for the latter to use the line in order to maximise line utilization.[75] In FY2018/19, total utilization reached 362,710 tons.[76]

Standard Gauge Railway

On August 3, 2022, during a state visit by Zambian president Hakainde Hichilema to Tanzania, the presidents of both nations issued a joint statement to launch a new project to revitalize the railway and build to Standard gauge through a Public Private Partnership.[77]

Statistics

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: FY1977/78 to FY1988/89;[78] FY2006/07 to FY2009/10;[79] FY2014/15;[6] FY2013/14[80] FY2015/16;[74] FY2016/17 to FY2019/20[76] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: FY1977/78 to FY1988/89;[78] FY2019/20[76] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Social impact

The TAZARA has had a strong impact on the rural regions along route. In the 1970s, the Tanzanian government resettled villagers into ujamaa villages that were near the railway.[32] The villages were tasked with providing security for the railway against foreign sabotage.[81] As the Tanzanian economy liberalized in the 1990s, the villagers began to use the railway to trade local produce.[32]

The railway also enabled settlers to move to the fertile Kilombero River Valley, between Mbeya and Kidatu, to grow cash crops such as rice and vegetables that they can readily ship to other communities.[32] As the TAZARA traverses diverse ecosystems, it facilitates trade in local produce across previously isolated communities, including maize, beans and vegetables from the highlands of Makambako, rice from Ifakara, oranges from Mlimba, and bananas from Mngeta and Idete.[32] The TAZARA ran the kipsi shuttle trains in the "passenger belt" of southern Tanzania to serve the region.[32] Many settlements have grown into large towns and districts.[82]

The TAZARA also spurred other large-scale economic developments in the region, including a hydroelectric power plant at Kidatu and a paper mill at Rufiji.

The TAZARA Railway Authority has also become a large state employer. In 40 years of operation, as many as one million people have been employed by the railway.[82] Chinese involvement has also been credited for increasing the opportunities of women to enter male-dominated jobs such as train driver.[83]

Legacy

The TAZARA remains an enduring symbol of the solidarity of the developing world and Chinese support for African independence and development. When Beijing hosted the 2008 Summer Olympic Games, the starting point of the torch relay in Tanzania was the grand terminal of the TAZARA.[84]

The difficulties with TAZARA made the Chinese government wary about funding other rail projects in Africa. China would not complete another new main line railway in Africa for another 41 years. A new era in Chinese railway construction in Africa began in 2016–2017 with the inauguration of the Abuja–Kaduna Railway in Nigeria, the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway in Ethiopia and Djibouti, and the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway in Kenya. To avoid repeating the problems of TAZARA, the Chinese government took measures to limit the financial and operational risk of the new railways. TAZARA had been 100% funded by an interest-free loan from China, but the new railways were financed through interest-bearing loans and required the recipient government to supply matching funds.[85] TAZARA had been handed over immediately to the Tanzanian and Zambian governments, but most of the new railways were concessioned to Chinese operating companies for the first 3–5 years.[86][87]

See also

- East African Railway Master Plan

- Tanzania Railways Corporation

- Transport in Tanzania

- Transport in Zambia

- Zambia Railways

- Railway stations in Tanzania

- Railway stations in Zambia

- List of tunnels by location

- Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway

Footnotes

- $406 million in 1970 was the equivalent of US $2.35 billion in 2011

References

- Thomas W. Robinson and David L. Shambaugh. Chinese Foreign Policy: theory and practice, 1994. Page 287.

- Brautigam 2010: 40

- (Chinese) 记者重走我国援建的坦赞铁路:年久失修常晚点 新华社-瞭望东方周刊 2010-08-04

- "Tanzania‐Zambia Railway: a Bridge to China?". New York Times. 29 January 1971.

- "Services". Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

With a designed capacity of five (5) million tonnes of freight per annum ...

- "Tazara's new CEO pledges to revive Chinese-built railway line". Xinhuanet. Xinhua News Agency. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016.

- Route Map & Profile Tazarasite.com

- Philip Briggs, Tanzania: With Zanzibar, Pemba and Mafia Bradt Travel Guides, 2009 ISBN 1841622885 P. 475

- Meandering through inhospitable terrainsTazarasite.com

- "Adjustment to the passenger train running schedules - TAZARA". 4 February 2016. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Amy Fallon, "Throwing the Tanzania-Zambia Railway a Lifeline" IPS 2013-12-11

- "Luxury Train Club - Pride of Africa Rovos Rail". 25 June 2012. Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- Kolumbia, Louis (29 October 2012). "Dar train services begin". The Citizen (Tanzania). Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- "Services". Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

The TAZARA railway line is designed with a 1067mm-gauge, which allows through traffic operations with other Southern African railways, such as Spoornet of South Africa, Botswana Railways, National Railways of Zimbabwe, Zambia Railways Limited Namibia Railways, Mozambique Railways and Societe Nationale Des Chemins De Fer Du Congo Sarl (SNCC) of the DRC.

- "Types of Gauges & Links" Tazarasite.com

- Railways Africa 2008/1 p8

- "East African Railways Master Plan". Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- "TAZARA Expansion Project Brief" (PDF). Tripartite and IGAD Investment Conference, 28–29 September 2011, Nairobi.

- Harden, Blaine (7 July 1987). "The Little Railroad that Could". The Washington Post.

- Batwell, John (6 March 2014). "Tazara orders more Chinese locomotives". International Railway Journal.

TANZANIA-Zambia Railway Authority (Tazara) has awarded CSR Qishuyan Locomotive Company, China, a contract worth US$12.5m to supply four additional type SDD20 diesel locomotives for use on its 1860km line between Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania, and New Kapiri Mposhi in Zambia.

- "TAZARA, Chinese firm sign pact for four locomotives". Lusaka Voice. 1 March 2014.

TAZARA now has a fleet of about 16 mainline locomotives at its disposal, six of the SDD20 were acquired recently while the remaining 10 were the old Diesel Electric U30C Locomotives aged over 25 years whose reliability has reduced drastically due to overuse and lack of maintenance.

- "Types of Freight and Vehicles". Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

The CK6 diesel locomotive is a diesel-hydraulic locomotive manufactured for TAZARA by CSR Chengdu Co, Ltd of China. ... It is suitable for the shunting and transfer services only.

- Brun, Ellen; Hersh, Jacques (2011). "2, footnote 25". Socialist Korea: A Case Study of Historical Development. Monthly Review Press. pp. 64–5.

- Hall & Peyman 1976: 31

- Hall & Peyman 1976: 32

- Bailey, Martin (1976). Freedom Railway: China and the Tanzania-Zambia Link. London: Rex Collings. ISBN 0860360245.

- "How it all began" Tazarasite.com

- Altorfer-Ong 2009: PDF 9

- Altorfer-Ong 2009: PDF 9-10

- Charles, John L. Westward Go Young Man: The Reminiscences of Les Charles, (CNAC Consultants, 1978)

- Hall & Peyman 1976: 87–88

- Jamie Monson, "Freedom Railway: The unexpected successes of a Cold War development project" Boston Review 2004-12-01

- Altorfer-Ong 2009: PDF 6

- Altorfer-Ong 2009: PDF 16

- Altorfer-Ong 2009: PDF 16-17

- Altorfer-Ong 2009: PDF 22-23

- Hall and Peyman, p. 85

- Hall and Peyman, p. 80

- Altorfer-Ong 2009: PDF 24

- Hall and Peyman, p.98

- Monson 2009: 6

- Altorfer-Ong 2009: PDF 26

- Mohr, Charles (26 March 1970). "American and Red Chinese Workers Reported to Have Clashed in Tanzania". The New York Times.

- Hall & Peyman 1976: 124

- Brautigam 2010: 163

- (Chinese) 【中国输出】坦赞铁路今昔 2009-09-22

- Monson 2009: 36

- Monson 2009: 33

- Monson 2009: 58

- Hall & Peyman 1976: 127

- "TAZARA: The Uhuru Railway…" Zambia Daily Mail 2014-03-25

- Hall & Peyman 1976: 138–139

- "Tanzania Greets Train". The New York Times. Agence France Presse. 25 October 1975.

- Copper, John Franklin (1979). "China's Foreign Aid in 1978". Occasional Papers/Reprints Series in Contemporary Asian Studies. 29 (8).

- Preston 2005: 161

- Petter-Bowyer, P. J. H. (2003). Winds of Destruction: The Autobiography of a Rhodesian Combat Pilot. Johannesburg: 30° South Publ. p. 369. ISBN 9780958489034.

- Regional Transport Development, Dar es Salaam Corridor Project (TAZARA) Project No. 690-0240, "Interim Project Evaluation", November 1989

- Brautigam 2010: 84

- Tanzania-Zambia Railway Authority, "TAZARA Ten Year Development Plan" Documentation from Donors Conference, 2-3 February 1988

- Forman, J. F. (May 1987). "Identified Improvements to the Equipment Fleet of the TAZARA Railway" (PDF). United States Agency for International Development.

- De Leuw, Cather International Limited, "Final Report of Train Operations Improvement Study" Presented to the USAID, Harare, Zimbabwe 16 December 1992

- Adam, Christopher; Collier, Paul; Gondwe, Michael, eds. (2014). Zambia: Building Prosperity from Resource Wealth. Oxford University Press. p. 279. ISBN 9780191636264.

- Amos Chanda, "Angola, Zambia to reconstruct Benguela railway" Southern African News Features SANF 05 No. 39 April 2005

- "Freight train will link Mozambique, Zimbabwe and Zambia" Macauhub 11 September 2015

- "Save the 'Uhuru Railway' from collapse" Archived 14 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine "This Day", Wednesday, 29 October 2008.

- Amani, Victor (27 May 2011). "Strikes cost Tazara 6bn shillings in revenue in a year".

- "Tazara receives US$42 million railway funding from China" African Review 2012-10-01

- [https://online.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20131120-702947.html "Tazara Railway Accident Hits Zambia Copper Exports" Wall Street Journal 2013-11-20

- Editor, Chief (12 January 2010). "Zambia : China injects $39m into TAZARA operations". Retrieved 11 January 2017.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Southern Times, June 2010

- "TAZARA seeks funding from shareholders". Daily News. 2 January 2012.

- TAZARA to change management structure DailyNews Online 2014-03-24

- UK, DVV Media. "TAZARA takes delivery of locos and coaches". Retrieved 11 January 2017.

- "Tanzania: TAZARA Sets to Double Cargo Movement By June 2017" Tanzania Daily News (Dar es Salaam) 11 July 2016

- "South African firm Calabash Freight to use Tanzania-Zambia Railway". Reuters. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- "Performance results for 2019/2020". TAZARA. Retrieved 14 March 2021.

- "Tanzania, Zambia agree to upgrade Tazara to SGR level". The Citizen. 3 August 2022. Retrieved 4 August 2022.

- "Regional Transport Development Dar es Salaam Corridor Project (TAZARA) Project Number 690-0240 Interim Internal Project Evaluation" USAID, November 1989 pg. 8

- Christopher Adam,Paul Collier & Michael Gondwe, Zambia : building prosperity from resource wealth Oxford University Press, 2014, pg. 279

- Shem Oirere, "Tazara suffers huge fall in freight traffic", International Rail Journal 23 December 2015

- Monson 2009: 81-83

- "Achievements" Tazarasite.com

- Ng’uni, Chambo (7 December 2014). "Day with Evelyn Mwansa, Zambia's first female locomotive driver". TAZARA. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

When she joined TAZARA, she had no clue that one day she would be the first woman in Zambia to venture into an all-man dominated field. In those days it was unheard of for a woman to take up such a profession which was a preserve for men. "It is the Chinese (we were working with) who suggested that I start driving the train. For me, it never crossed my mind that I could drive a train. The Chinese motivated me and once I took on this challenge I never looked back", she said.

- Monson 2009: 154

- Omondi, George (2 September 2013). "Kenya to repay Chinese loan at floating rate". Business Daily Africa.

Transport secretary Michael Kamau said last month’s loan for the standard gauge railway (SGR), energy and wildlife protection was negotiated at a floating interest rate of 360 basis points above the London Interbank Offered Rate (Libor).... Other than the Chinese loan, the remaining part of Sh340 billion railway modernisation project will be financed by the recently introduced railway development levy.

- Yewondwossen, Muluken (22 December 2016). "Two Chinese firms to overseas Ethio-Djibouti railway". Capital Ethiopia Newspaper. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Maundu, Pius. "Mombasa-Nairobi section of the SGR to be complete by June next year".

Sources

- Altorfer-Ong, Alicia (2009). "Tanzanian 'Freedom' and Chinese 'Friendship' in 1965: laying the tracks for the TanZam rail link" (PDF). LSE Ideas. London School of Economics (LSE): 655–670. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 October 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2010.

- Ball, Peter (17 November 2015). "The Tanzania - Zambia Railway". The Heritage Portal. Retrieved 23 August 2021.

- Brautigam, Deborah (2010). The Dragon's Gift: The Real Story of China in Africa. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199550227.

- Hall, Richard Seymour; Peyman, Hugh (1976). The Great Uhuru Railway: China's Showpiece in Africa. Gollancz. ISBN 057502089X.

- Monson, Jamie (2009). Africa's Freedom Railway: How a Chinese Development Project Changed Lives and Livelihoods in Tanzania. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0253002815.

- Preston, Matthew (2005). Ending Civil War: Rhodesia and Lebanon in Perspective. Tauris Academic Studies. ISBN 978-1850435792.

- Wolfe, Alvin W. "Tanzania-Zambia Railway: Escape Route from Neocolonial Control?" Nonaligned Third World Annual. St. Louis: Books International of D.H.-T.E. International, 1970. 92-103.