British Indian Ocean Territory

The British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) is a disputed Overseas Territory of the United Kingdom situated in the Indian Ocean, halfway between Tanzania and Indonesia. The territory comprises the seven atolls of the Chagos Archipelago with over 1,000 individual islands – many very small – amounting to a total land area of 60 square kilometres (23 square miles).[2] The largest and most southerly island is Diego Garcia, 27 square kilometres (10 square miles), the site of a Joint Military Facility of the United Kingdom and the United States.[5]

British Indian Ocean Territory | |

|---|---|

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Motto: In Tutela Nostra Limuria Limuria is in our trust | |

| Anthem: God Save the King | |

| |

| Sovereign state | |

| Capital and settlement | Camp Thunder Cove on Diego Garcia 7°18′S 72°24′E |

| Official languages | English |

| Ethnic groups (2001) |

|

| Government | Dependency under a constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

• Commissioner | Paul Candler |

• Deputy Commissioner | Becky Richards |

• Administrator | Balraj Dhanda |

| Government of the United Kingdom | |

• Minister | Nigel Adams MP |

| Area | |

• Total | 54,000 km2 (21,000 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 99.89 |

• Land | 60 km2 (23 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• Non-permanent 2018 estimate | |

• Permanent | 0 |

• Density | 50.0/km2 (129.5/sq mi) |

| Currency |

|

| Time zone | UTC+06 |

| Mains electricity | 230 Volt, 50 Hertz |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +246 |

| UK postcode | BBND 1ZZ |

| ISO 3166 code | IO |

| Internet TLD | .io |

| Website | biot.gov.io |

The only inhabitants are British and United States military personnel, and associated contractors, who collectively number around 3,000 (2018 figures).[2] The forced removal of Chagossians from the Chagos Archipelago occurred between 1968 and 1973. The Chagossians, then numbering about 2,000 people, were expelled by the UK government to Mauritius and Seychelles in order to construct the military base. Today, the exiled Chagossians are still trying to return, saying that the forced expulsion and dispossession was unlawful, but the UK government has repeatedly denied them the right of return.[6][7] The islands are off-limits to Chagossians, casual tourists, and the media.

Since the 1980s, the Government of Mauritius has sought to regain control over the Chagos Archipelago, which was separated from the then Crown Colony of Mauritius by the UK in 1965 to form the British Indian Ocean Territory. A February 2019 advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice called for the islands to be given to Mauritius. Since this, the United Nations General Assembly and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea have reached similar decisions. On 3 November 2022, it was announced that the UK and Mauritius had decided to begin negotiations on sovereignty over the British Indian Ocean Territory, taking into account the international legal proceedings.[8]

History

Maldivian mariners knew the Chagos Islands well.[9] In Maldivian lore, they are known as Fōlhavahi or Hollhavai (the latter name in the closer Southern Maldives). According to Southern Maldivian oral tradition, traders and fishermen were occasionally lost at sea and got stranded on one of the islands of the Chagos. Eventually they were rescued and brought back home. However, these islands were judged to be too far away from the seat of the Maldivian crown to be settled permanently by them. Thus, for many centuries the Chagos were ignored by their northern neighbours.

Early settlement

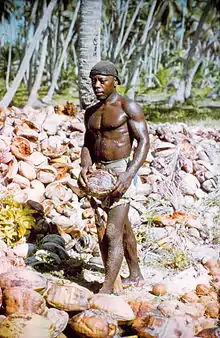

The islands of Chagos Archipelago were charted by Vasco da Gama in the early 16th century, and then claimed in the 18th century by France as a possession of Mauritius. They were first settled in the 18th century by African slaves and Indian contractors brought by Franco-Mauritians to found coconut plantations.[10] In 1810, Mauritius was captured by the United Kingdom, and France subsequently ceded the territory in the Treaty of Paris in 1814.

Formation of BIOT

In 1965, the United Kingdom split the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius and the islands of Aldabra, Farquhar and Desroches (Des Roches) from the Seychelles to form the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT). The purpose was to allow the construction of military facilities for the mutual benefit of the United Kingdom and the United States of America. The islands were formally established as an overseas territory of the United Kingdom on 8 November 1965.[11]

A few weeks after the decision to detach the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 2066 on 16 December 1965, which stated that this detachment of part of the colonial territory of Mauritius was against customary international law as recorded earlier in the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples of 14 December 1960. This stated that "Any attempt aimed at the partial or total disruption of the national unity and the territorial integrity of a country is incompatible with the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations".[12][13] Largely because of the detachment of the islands, the International Court of Justice determined in 2019 that the decolonisation of Mauritius was still not lawfully completed.[14]

Mauritius became an independent Commonwealth realm in March 1968, and subsequently became a republic, also within the Commonwealth, in March 1992.

On 23 June 1976, Aldabra, Farquhar and Desroches were returned to the Seychelles which became independent as a republic on 29 June 1976; the islands now form part of the Outer Islands district of the Seychelles. Subsequently, the territory has consisted only of the six main island groups comprising the Chagos Archipelago.

Forced depopulation

In 1966, the UK Government purchased the privately owned copra plantations and closed them. Over the next five years, the British authorities forcibly and clandestinely removed the entire population of about 2,000 people, known as Chagossians (or Ilois), from Diego Garcia and two other Chagos atolls, Peros Banhos and Salomon Islands, to Mauritius.[15] In 1971, the United Kingdom and the United States signed a treaty, leasing the island of Diego Garcia to the US military for the purposes of building a large air and naval base on the island. The deal was important to the UK Government, as the United States granted it a substantial discount on the purchase of Polaris nuclear missiles in return for the use of the islands as a base.[16] The strategic location of the island was also significant at the centre of the Indian Ocean, and to counter any Soviet threat in the region.

During the 1980s, Mauritius asserted a claim to sovereignty for the territory, citing the 1965 separation as illegal under international law, despite their apparent agreement at the time. The UK does not recognise Mauritius' claim, but has agreed to cede the territory to Mauritius when it is no longer required for defence purposes.[17] The Seychelles also made a sovereignty claim on the islands.[2]

The islanders, who now mainly reside in Mauritius and Seychelles, have continually asserted their right to return to Diego Garcia, winning important legal victories in the High Court of England and Wales in 2000, 2006, and 2007. However, in the High Court and Court of Appeal in 2003 and 2004, the islanders' application for further compensation on top of the £14.5 million value package of compensation they had already received was dismissed by the court.[18]

On 11 May 2006, the High Court ruled that a 2004 Order in Council preventing the Chagossians' resettlement of the islands was unlawful, and consequently that the Chagossians were entitled to return to the outer islands of the Chagos Archipelago.[19] On 23 May 2007, this was confirmed by the Court of Appeal.[20] In a visit sponsored by the UK Government, the islanders visited Diego Garcia and other islands on 3 April 2006 for humanitarian purposes, including the tending of the graves of their ancestors.[21] On 22 October 2008, the UK Government won an appeal to the House of Lords regarding the royal prerogative used to continue excluding the Chagossians from their homeland.[22][23]

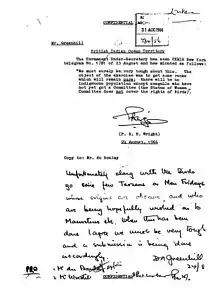

According to a WikiLeaks disclosure document,[24] in a calculated move in 2009 to prevent Chagossians returning to their homeland, the UK proposed that the BIOT become a 'marine reserve' with the aim of preventing the former inhabitants from returning to the islands. The summary of the diplomatic cable is as follows:

HMG would like to establish a 'marine park' or 'reserve' providing comprehensive environmental protection to the reefs and waters of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), a senior Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) official informed Polcouns on 12 May. The official insisted that the establishment of a marine park – the world's largest – would in no way impinge on USG use of the BIOT, including Diego Garcia, for military purposes. He agreed that the UK and U.S. should carefully negotiate the details of the marine reserve to assure that U.S. interests were safeguarded and the strategic value of BIOT was upheld. He said that the BIOT's former inhabitants would find it difficult, if not impossible, to pursue their claim for resettlement on the islands if the entire Chagos Archipelago were a marine reserve.

The UK Government established a marine reserve in April 2010, to mixed reactions from Chagossians. While the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office claimed that it was an environmental move as well as a necessary move to improve the coral populations off east Africa, and therefore sub-Saharan marine supplies, some Chagossians claimed that the reserve would prevent any resettlement due to the inability to fish in protected areas. The Chagossian UK-based Diego Garcian Society stated that it welcomed the marine reserve, noting that it was in the interest of Chagossians to have the area protected while they were exiled and that it could be renegotiated upon resettlement. The Foreign Office claimed the reserve was made "without prejudice to the outcome of proceedings before the European Court of Human Rights".[25] (That court's 2012 decision was not in favour of the Islanders anyway.)[26]

On 1 December 2010, a leaked US Embassy London diplomatic cable exposed British and US communications in creating the marine nature reserve. The cable relays exchanges between US political counselor Richard Mills, and British Foreign and Commonwealth Office official Colin Roberts, in which Roberts "asserted that establishing a marine park would, in effect, put paid to resettlement claims of the archipelago's former residents".[27] Richard Mills concludes: "Establishing a marine reserve might, indeed, as the FCO's Roberts stated, be the most effective long-term way to prevent any of the Chagos Islands' former inhabitants or their descendants from resettling in the BIOT".[27] The cable (reference ID '09LONDON1156') was classified as confidential and "no foreigners", and leaked as part of the Cablegate cache.

Development of BIOT

Work on the military base commenced in 1971, with a large airbase with several long range runways constructed, as well as a harbour suitable for large naval vessels. Although classed as a joint UK/US base, in practice it is primarily staffed by the US military, although the UK maintains a garrison at all times, and Royal Air Force (RAF) long-range patrol aircraft are deployed there. The United States Air Force (USAF) used the base during the 1991 Gulf War and the 2001 War in Afghanistan, as well as the 2003 Iraq War.

In 1990, the first BIOT flag was unfurled. This flag, which also contains the Union Jack, has depictions of the Indian Ocean, where the islands are located, in the form of white and blue wavy lines and also a palm tree rising above the British crown.[28] The US-UK arrangement which established the territory for defence purposes initially was in place from 1966 to 2016, and has subsequently been renewed to continue until 2036. The announcement was accompanied by a pledge of £40 million in compensation to former residents.[29]

International opinion and rulings

On 22 May 2019, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted a resolution, affirming that "the Chagos Archipelago forms an integral part of the territory of Mauritius", citing the February 2019 advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the separation of the archipelago from Mauritius.[30] In its advisory opinion, the Court concluded that "the process of decolonisation of Mauritius was not lawfully completed when that country acceded to independence", and that "the United Kingdom is under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible".[31] The motion was approved by a majority vote with 116 member states voting for and 6 against.[30] On 28 January 2021, the United Nation's International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea ruled, in a dispute between Mauritius and Maldives on their maritime boundary, that the United Kingdom has no sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago, and that Mauritius is sovereign there. The United Kingdom disputes and does not recognise the tribunal's decision.[32][33]

The Universal Postal Union (UPU), which has jurisdiction over international mail among treaty signatory states, voted in 2021 to ban the use of British postage stamps on mail to and from BIOT, instead requiring Mauritian stamps to be used.[34]

On 3 November 2022, the British Foreign Secretary James Cleverly announced that the UK and Mauritius had decided to begin negotiations on sovereignty over the British Indian Ocean Territory, taking into account international legal proceedings. Both states had agreed to ensure the continued operation of the joint UK/US military base on Diego Garcia.[8][35]

2022 Mauritian expedition

In February 2022, exiled islanders made their first unsupervised visit to an island in the Chagos Archipelago.[36] The Permanent Representative of Mauritius to the United Nations, Jagdish Koonjul, raised the Mauritian flag on Peros Banhos.[37][38] The main purpose of the fifteen-day Mauritian expedition is to survey the unclaimed Blenheim Reef, to discover for a forthcoming International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea hearing if it is exposed at high tide so is claimable.[39][40] The chartered Bleu De Nîmes was shadowed by a British fisheries protection vessel.[41]

Government

.jpg.webp)

As a territory of the United Kingdom, the head of state is King Charles III. There is no Governor appointed to represent the King in the territory, as there are no permanent inhabitants (as is also the case in South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands and the British Antarctic Territory). The territory is one of eight dependencies in the Indian Ocean, alongside the Ashmore and Cartier Islands, Christmas Island, the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and Heard Island and McDonald Islands, all Australian possessions; the French Southern and Antarctic Lands, with the French Scattered Islands in the Indian Ocean and its dependencies of Tromelin and the Glorioso Islands; along with French Mayotte and Réunion.

The head of government is the Commissioner, currently Paul Candler, who is also Director of Overseas Territories in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and Commissioner of the British Antarctic Territory; the Deputy Commissioner is Stephen Hilton, and the Administrator is Kit Pyman, and all senior officials reside in the United Kingdom. The Commissioner's Representative in the territory is the officer commanding the detachment of British forces.[42]

The laws of the territory are based on the constitution, currently set out in the British Indian Ocean Territory (Constitution) Order 2004, which gives the Commissioner power to make laws for the peace, order and good government of the territory.[43][42][44] If the Commissioner has not made a law on a particular topic then, in most circumstances, the laws that apply in the territory are the same as those that apply in England and Wales under the terms of the Courts Ordinance 1983.[45] There is no legislature (and no elections) as there are no permanent inhabitants, although a small legal system has been established for the jurisdiction. As almost all residents of the BIOT are members of the United States military, however, in practice crimes are more commonly charged under United States military law.

Applicable treaties between the United Kingdom and the United States govern the use of the military base. The first exchange of notes, signed on 30 December 1966, constituted an agreement concerning the availability for defence purposes of the British Indian Ocean Territory.[46] This was followed by agreements on the construction of a communications facility (1972), naval support facility (1976), construction contracts (1987), and a monitoring facility (1999). The United States is reportedly required to ask permission of the United Kingdom to use the base for offensive military action.

Naval Party 1002 and MV Grampian Frontier

Naval Party 1002 (NP 1002) is directly present in the territory, and is composed of both Royal Navy and Royal Marine personnel. NP 1002 is responsible for civil administration and enforcement. Its members are tasked with policing and carrying out customs duties. Royal Marines in the territory also reportedly form a security detachment.[47]

Prior to 2017, the BIOT patrol vessel, MV Pacific Marlin, was based in Diego Garcia. It was operated by the Swire Pacific Offshore Group. The Pacific Marlin patrolled the marine reserve all year, and since the marine reserve was designated in April 2010, the number of apprehensions of illegal vessels within the area has increased. The ship was built in 1978 as an ocean-going tug. It is 57.7 metres (189 feet 4 inches) long, with a draught of 3.8 metres (12 feet 6 inches), and gross tonnage of 1,200 tons. It has a maximum speed of 12.5 knots (23.2 kilometres per hour; 14.4 miles per hour) with an economic speed of 11 knots (20 kilometres per hour; 13 miles per hour), permitting a range of about 18,000 nautical miles (33,000 kilometres; 21,000 miles) and fuel endurance of 68 days. It was the oldest vessel in the Swire fleet.[48] Pacific Marlin reportedly spent about 54% of her taskings on fishery patrol duties, and a further 19% on military patrol duties.[49]

In 2016, a new contract was signed with Scottish-based North Star Shipping for the use of the vessel MV Grampian Frontier. She is a 70 metres (230 feet) vessel carrying up to 24 personnel, and fulfils both the patrol and research role.[49] The vessel reportedly operates in conjunction with personnel from NP 1002 on both fisheries and military enforcement tasks / exercises, and also carries scientists / researchers involved in a range of research work, particularly conservation.[50] In 2022, Grampian Frontier tracked a Mauritian-charted vessel temporarily bringing Chagossian exiles to Blenheim Reef in the archipelego.[51]

Geography

The territory is an archipelago of 55 islands,[42] the largest being Diego Garcia, the only inhabited island, which accounts for almost half of the territory's total land area (60 square kilometres (23 square miles)). The terrain is flat and low, with most areas not exceeding two metres (6 ft 7 in) above sea level. In 2010, 545,000 square kilometres (210,000 square miles) of ocean around the islands was declared a marine reserve.[25]

The British Indian Ocean Territory (Constitution) Order 2004 defines the territory as comprising the following islands or groups of islands:

- Diego Garcia

- Three Brothers Islands

- Egmont Islands

- Nelson Island

- Peros Banhos

- Eagle Islands

- Salomon Islands

- Danger Islands

As indicated above, the territory also included Aldabra, Farquhar and Desroches between 1965 and 1976; the latter group of islands is located north of Madagascar and were annexed from and returned to the Seychelles.

Climate

The climate is tropical marine; hot, humid, and moderated by trade winds.[52]

Transport

In terms of transportation on Diego Garcia, the island has short stretches of paved road between the port and airfield, and on its streets; transport is mostly by bicycle and on foot. The island had many wagonways, which were donkey-hauled narrow gauge railways for the transport of coconut wagons. These are no longer in use and have deteriorated.[53]

Diego Garcia's military base is home to the territory's only airport. At 3,000 metres (9,800 feet) long, the runway is capable of supporting heavy US Air Force bombers such as the B-52, and would have been able to support the Space Shuttle in the event of a mission abort.[54] It also has a major naval seaport,[55] and there is also a marina bus service along the main road of the island.[56]

Yacht crews seeking safe passage across the Indian Ocean may apply for a mooring permit for the uninhabited Outer Islands (beyond Diego Garcia),[57] but must not approach within 3 nautical miles (5.6 kilometres; 3.5 miles) land on or anchor at islands designated as Strict Nature Reserves, or the nature reserve within the Peros Banhos atoll. Unauthorised vessels or persons are not permitted access to Diego Garcia, and no unauthorised vessel is permitted to approach within three nautical miles of the island.[58]

Conservation

On 1 April 2010, the Chagos Marine Protected Area (MPA) was declared to cover the waters around the Chagos Archipelago. However, Mauritius objected, stating this was contrary to its legal rights, and on 18 March 2015, the Permanent Court of Arbitration ruled that the MPA was illegal under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, as Mauritius had legally binding rights to fish in the waters surrounding the archipelago, to an eventual return of the archipelago, and to the preservation of any minerals or oil discovered in or near the archipelago prior to its return.[59][60]

The MPA's declaration doubled the total area of environmental no-take zones worldwide. The benefits of protecting this area are described as follows:

- Providing an environmental benchmark for other areas (unlike the rest of the world, the BIOT has been relatively untouched by man's actions);

- Providing a natural laboratory to help understand climate change;

- An opportunity for research related to marine science, biodiversity, and climate change;

- Acting as a reserve for species in danger in other areas; and

- Providing an export supply of surplus juveniles, larvae, seeds, and spores to help with output in neighbouring areas.[61]

The area had already been declared an Environmental (Preservation and Protection) Zone, but since the establishment of the MPA, fishing has no longer been permitted in the area.

The BIOT Administration has facilitated several visits to the territory by the eldest Chagossians, and environmental training for UK-based Chagossians that allows some to become involved in scientific work (alongside visiting scientists).[62]

Demographics

The British Indian Ocean Territory (Constitution) Order 2004 states that "no person has the right of abode" in the territory as it "was constituted and is set aside to be available for the defence purposes of the Government of the United Kingdom and the Government of the United States of America", and accordingly, "no person is entitled to enter or be present in the Territory except as authorised" by its laws.

As there is no permanent population, or census, information on the demographics of the territory is limited; the size of the population is related to its offensive requirements. Diego Garcia, with a land area of 27 square kilometres (10 square miles), is the only inhabited island in the territory, and therefore has an estimated average population density of around 110 persons per km2. Diego Garcia's population is normally limited to official visitors and military-essential personnel only, and family members are not authorised to travel to Diego Garcia (the island therefore has no schools). Personnel may not travel to the island for leave, but they may transit through Diego Garcia to connect with follow-on flights.[63] The population in 1995 was estimated to be approximately 3,300; i.e. 1,700 UK and US military personnel and 1,500 civilian contractors. The total population was reportedly 4,000 persons in 2006, of whom 2,200 were US military personnel or contractors, 1,400 were Overseas Filipino Worker contract staff, 300 were Mauritian contract staff, and 100 were members of the British Armed Forces. The population had decreased to around 3,000 persons in 2018.[2] United Nations population statistics indicate that island's population is comparable to that of the Falkland Islands. The remainder of the archipelago is ordinarily uninhabited.

Marooned asylum seekers

In October 2021, 89 Sri Lankan Tamils, including 20 children, who were traveling from India to Canada in a vessel which ran into distress, were intercepted and escorted to Diego Garcia by the British military. After more than seven months without a resolution to their situation on the island, 42 of them started a hunger strike. London solicitors for 81 of them say they have been given no information about how they may claim international protection, or how long they will be kept on Diego Garcia.[64]

On 10 April 2022, a further 30 asylum seekers rescued from a second vessel joined the 89 Sri Lankans, who are being kept in a tented fenced-in camp.[65][66] Britain has not extended many humanitarian treaties to the unpopulated islands, including the 1951 Refugee Convention and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which makes the legal situation difficult.[67][68] On 25 October 2022, the British government stated it "remains committed to supporting their departure" and they "will not be permitted to make a claim for asylum in the UK".[69]

Further small boats with Tamil refugees that ran into difficulties were escorted to Diego Garcia, where repairs were made, and they were permitted to leave. One boat carrying 46 people went on to the French territory of Réunion.[70][68]

Economy

.svg.png.webp)

All economic activity is concentrated on Diego Garcia, where joint UK/US defence facilities are located. Construction projects and the operation of various services needed to support the military installations are carried out by military, and contract employees from Britain, Mauritius, the Philippines, and the United States. There are no industrial or agricultural activities on the islands. Until the creation of the marine sanctuary, the licensing of commercial fishing provided an annual income of about US$1 million for the territory.[71]

Services

The Navy Morale, Welfare and Recreation (MWR) section provides several facilities on Diego Garcia, including a library, outdoor cinema, shops, and sports centres, with prices in US dollars. The BIOT Post Office provides outbound postal services, and postage stamps have been issued for the territory since 17 January 1968. As the territory was originally part of Mauritius and the Seychelles, these stamps were denominated in rupees until 1992. However, after that date they were issued in denominations of Pound sterling, which is the official currency of the territory. Basic medical services are provided, with the option of medical evacuation where required, and the territory has no schools.[72]

Telecommunications

Cable & Wireless started operating telecommunications services in 1982, under licence from the UK Government. In April 2013, the company was acquired by the Batelco Group, and Cable & Wireless (Diego Garcia) Ltd subsequently changed its name to Sure (Diego Garcia) Ltd; Sure International is the corporate division of the business.

Due to its geographic location in proximity to the Equator, with unobstructed views to the horizon, Diego Garcia has access to a relatively large number of geosynchronous satellites over the Indian and eastern Atlantic Oceans, and the island is home to Diego Garcia Station (DGS), a remote tracking station making up part of the United States Space Force's Satellite Control Network (SCN); the station has two sides to provide enhanced tracking capabilities for AFSCN users.[73]

Broadcasting

The territory has three FM radio broadcast stations; provided by the American Forces Network (AFN) and British Forces Broadcasting Service (BFBS). Amateur radio operations occur from Diego Garcia, using the British callsign prefix VQ9. An amateur club station, VQ9X, was sponsored by the US Navy for use by operators both licensed in their home country and possessing a VQ9 callsign issued by the local British Indian Ocean Territory representative.[74] However, the US Navy closed the station in early 2013, and any future licensed amateurs wishing to operate from the island would therefore have had to provide their own antenna and radio equipment.[75]

.io domain name

The .io (Indian Ocean) country-code top-level domain was delegated by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority (IANA) to British entrepreneur Paul Kane in 1997, and was operated for private benefit under the trade name 'Internet Computer Bureau' from 1997 until 2017.[76] In April 2017, Paul Kane sold the Internet Computer Bureau holding company to privately held domain name registry services provider Afilias for US$70.17 m in cash.[77]

In July 2021, the Chagos Refugees Group UK submitted a complaint to the Irish government against Paul Kane and Afilias, seeking repatriation of the .io domain, and payment of back royalties from the $7 m per year in revenue generated by the domain.[78]

Sports

- Chagos Islands national football team

See also

- British Overseas Territories

- Chagos Archipelago sovereignty dispute

- Index of United Kingdom–related articles

- Legal Consequences of the Separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965

- List of sovereign states and dependent territories in the Indian Ocean

References

- Citations

- "FCO country profile - British Indian Ocean Territory". Archived from the original on 10 June 2010. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- "British Indian Ocean Territory". World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 27 March 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "British Indian Ocean Territory Currency". GreenwichMeantime.com. Archived from the original on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- "Launch of first commemorative British Indian Ocean Territory coin". coinnews.net. Pobjoy Mint Ltd. 17 May 2009. Retrieved 4 April 2014.

- Chirayu Thakkar (12 July 2021). "Overcoming the Diego Garcia stalemate". WarOnTheRocks.com.

- "Mauritius profile". BBC News. 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- "Historical background – what happened to the Chagos Archipelago?". chagosinternational.org. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2012.

- Wintour, Patrick (3 November 2022). "UK agrees to negotiate with Mauritius over handover of Chagos Islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- Xavier Romero-Frias (1999). "1 A Seafaring Nation". The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom. Barcelona: Nova Ethnographia Indica. p. 19. ISBN 84-7254-801-5.

- Vine, David (17 April 2008). "Introducing the other Guantanamo". atimes.com. Asia Times. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - United States Dept. of State. Office of the Geographer (1968). Commonwealth of Nations. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 15. Retrieved 7 November 2013 – via Google Books.

- "United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2066 (XX) - Question of Mauritius". United Nations. 16 December 1965. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- {{Cite book|url=https://www.open.edu/openlearn/society-politics-law/exploring-the-boundaries-international-law/content-section-0?active-tab=content-tab%7Ctitle=Exploring the boundaries of international law|publisher=[[The Open University|chapter-url=https://www.open.edu/openlearn/society-politics-law/exploring-the-boundaries-international-law/content-section-2.4%7Cchapter=2.4 Self-determination|access-date=2 February 2021}}

- "Legal consequences of the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965 - overview of the case". International Court of Justice. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Baker, Luke (25 May 2007). "The coral sea vista opened up by British judges". Reuters. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- Knapton, Sarah (21 October 2008). "Law Lords to rule on whether Chagos Islanders can finally return home". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- Foreign Affairs Committee (6 July 2008). "Seventh Report – Overseas Territories". House of Commons. p. 125. Retrieved 6 August 2009.

- "Chagos Islanders v Attorney General & Anor [2004] EWCA Civ 997 (22 July 2004)". bailii.org. BAILII. Retrieved 27 April 2021.

- The Queen on the application of Louis Olivier Bancoult v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, 1038 (Admin) (2006reporter=EWHC).

- Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs v The Queen (on the application of Bancoult), EWCA Civ 498 (2007).

- Reynolds, Paul (3 April 2006). "Paradise regained – for a few days". BBC News. Retrieved 27 April 2010.

- "Britain wins appeal over Chagos islanders' return home". Agence France-Press. 22 October 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- R (on the application of Bancoult) v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, UKHL 61 (2008).

- "HMG floats proposal for marine reserve covering Chagos Archipeligo (British Indian Ocean Territory)". The Daily Telegraph. 4 February 2011. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- "UK sets up Chagos Islands marine reserve". BBC News. 1 April 2010. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- "Chagos Islanders against the United Kingdom: Decision". European Court of Human Rights. 11 December 2012.

- "Cable 09LONDON1156_a". Wikileaks. 15 May 2009. Retrieved 23 February 2015.

- "British Indian Ocean Territory". WorldAtlas.com. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- Mance, Henry (16 November 2016). "Extended US lease blocks Chagossians' return home". Financial Times. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "General Assembly welcomes International Court of Justice opinion on Chagos Archipelago, adopts text calling for Mauritius' complete decolonisation". www.un.org. Retrieved 31 July 2020.

- "Advisory Opinion: Legal Consequences of the Separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965" (PDF). International Court of Justice. 25 February 2019. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- Harding, Andrew (28 January 2021). "UN court rules UK has no sovereignty over Chagos islands". BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "Dispute concerning delimitation of the Maritime Boundary between Mauritius and Maldives in the Indian Ocean (Mauritius/Maldives)" (PDF) (Press release). International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. 28 January 2021. ITLOS/Press 313. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- "British stamps banned from Chagos Islands in Indian Ocean". BBC News. 25 August 2021.

- Cleverly, James (3 November 2022). "Chagos Archipelago". Hansard. UK Parliament. HCWS354. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- Bowcott, Owen; Rinvolucri, Bruno (13 February 2022). "Exiled Chagos Islanders bask in return 'as pilgrims to abandoned place'". The Observer. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- Bowcott, Owen; Rinvolucri, Bruno (14 February 2022). "Mauritius formally challenges Britain's ownership of Chagos Islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- Flanagan, Jane (14 February 2022). "Mauritius plants flag on disputed Chagos islands". The Times. London. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- Bowcott, Owen; Rinvolucri, Bruno (13 February 2022). "Mauritius measures reef hoping to lay claim on Chagos Islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- Brewster, David; Bashfield, Samuel (13 February 2022). "An unclaimed reef adds a wrinkle to the dispute over Diego Garcia". The Lowy Interpreter. The Maritime Executive. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- Bowcott, Owen; Rinvolucri, Bruno (20 February 2022). "Chagossian exiles celebrate emotional return as UK tries to justify control". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- "Governance". BIOT. British Indian Ocean Territory Administration. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "British Indian Ocean Territory (Constitution) Order 2004 – a Freedom of Information request to Privy Council Office". WhatDoTheyKnow.com. 9 November 2012.

- Cormacain, Ronan (1 September 2013). "Prerogative legislation as the paradigm of bad law-making: the Chagos Islands". Commonwealth Law Bulletin. 39 (3): 487–508. doi:10.1080/03050718.2013.822317. S2CID 131408841 – via Taylor and Francis+NEJM.

- British Indian Ocean Territory Ordinance No 3 of the 1983 ("the Courts Ordinance"), Article 3.1.

- "Exchange of notes constituting an agreement concerning the availability for defense purposes of the British Indian Ocean Territory". UN Treaty Series. 603: 273. 1967. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Welcome to Diego Garcia" (PDF). public.navy.mil. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- Milmo, Cahal (28 March 2014). "Exclusive: British Government under fire for pollution of pristine lagoon". The Independent. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Patrol Vessel". The Chagos Archipelago. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- "The high point of our circumnavigation?". SailingSteelSapphire.com. 10 July 2020. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- Bowcutt, Owen; Rinvolucri, Bruno (20 February 2022). "Chagossian exiles celebrate emotional return as UK tries to justify control". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

- "HA08 - British Indian Ocean Territory". ctbto.org. Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty Organization. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Morris, Ted. "Diego Garcia – The Plantation". zianet.com.

- Pike, John (20 July 2007). "Space Shuttle landing sites". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- "US Naval Support Facility, Diego Garcia". www.cnic.navy.mil. US Navy. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "On the Chop's visit to Diego Garcia". TheBaltimoreChop.com. 12 October 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2013.

- "How to apply for a mooring permit". www.biot.gov.io. BIOT Administration. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Mooring site plots". www.biot.gov.io. BIOT Administration. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Bowcott, Owen; Jones, Sam (19 March 2015). "UN ruling raises hope of return for exiled Chagos islanders". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Chagos Marine Protected Area arbitration (Mauritius v. United Kingdom) (Press Release and Summary of Award)". Permanent Court of Arbitration. 19 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- North Sea Marine Cluster (2012). "Managing Marine Protected Areas" (PDF). NSMC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- "BIOT history". biot.gov.io. BIOT Administration. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "Visitor information". cnic.navy.mil. US Navy. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Siddique, Haroon (20 May 2022). "Tamil refugees detained by UK on Chagos Islands go on hunger strike". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 May 2022.

- Goldberg, Jacob (20 May 2022). "Asylum seekers stuck on Diego Garcia start hunger strike". AlJazeera.com. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Israel, Simon (10 June 2022). "Sri Lankans stranded in Diego Garcia after rescue from sinking". London, England: Channel 4 News. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Bashfield, Samuel (1 June 2022). "The BIOT: A judicial vacuum now consuming Tamil refugees". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 10 June 2022.

- Mellersh, Natasha (19 October 2022). "UK plans to deport Tamil refugees on British territory in Rwanda-style plan". InfoMigrants. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- Norman, Jesse (25 October 2022). "Diego Garcia: Asylum". UK Parliament. UIN 67039. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- Siddique, Haroon (16 October 2022). "UK accused of putting Tamil refugees at risk in Indian Ocean". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- "British Indian Ocean Territories". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 21 June 2004. col. 1219W.

- "Feasibility study for the resettlement of the British Indian Ocean Territory, Volume 1" (PDF). Parliament.uk. KPMG. 31 January 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "20th Space Control Squadron, Det 2". Peterson.af.mil. US Air Force. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Arneson, Larry (VQ9LA). "VQ9X Club Station". QSL.NET. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- Arneson, Larry (VQ9LA). "(Post of) May 24, 2013". Official VQ9X Facebook page. Retrieved 20 September 2013.

- Bridle, James. ".IO: British Indian Ocean Territory". Citizen Ex. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- Murphy, Kevin (9 November 2018). "Afilias bought .io for $70 million". Domain Incite. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Levy, Jonathan. "Complaint filed against Afilias Ltd. (Ireland) including its subsidiaries 101domain GRS Limited (Ireland), Internet Computer Bureau Limited (England & British Indian Ocean Territory), in respect of OECD guidelines violations in operation of ccTLD .io, before the Ireland OECD national contact point" (PDF). Chagos Refugees Group UK. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- Further reading

External links

- Official websites

- British Indian Ocean Territory Administration - official website

- British Indian Ocean Territory - UK Government site

- British Indian Ocean Territory - UK travel advice

- British Indian Ocean Territory - official map

- Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia - US Navy website

- Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia - YouTube

- Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia - Facebook

- Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty station, Diego Garcia

- BIOT Post Office

- Chagossian campaign

- UK Chagos Support Association

- Let Us Return USA - US Chagossian Support Group

- Christian Nauvel, "A Return from Exile in Sight? The Chagossians and their Struggle" (2006) 5 Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights 96–126 (retrieved 9 May 2011).

- Others

- Chagos Conservation Trust – a non-political charity whose aims are to promote conservation, scientific and historical research, and to advance education concerning the archipelago

- Sure Diego Garcia - telecommunications company, Diego Garcia

- Diego Garcia Online - information for Diego Garcia population

- British Indian Ocean Territory - The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency.

- EU relations with British Indian Ocean Territory (archived)

- Diego Garcia - timeline posted at the History Commons Archived 30 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Chagos Islands (BIOT) at Britlink – British Islands & Territories (archived)

.svg.png.webp)