Oresteia

The Oresteia (Ancient Greek: Ὀρέστεια) is a trilogy of Greek tragedies written by Aeschylus in the 5th century BC, concerning the murder of Agamemnon by Clytemnestra, the murder of Clytemnestra by Orestes, the trial of Orestes, the end of the curse on the House of Atreus and the pacification of the Erinyes. The trilogy—consisting of Agamemnon (Ἀγαμέμνων), The Libation Bearers (Χοηφόροι), and The Eumenides (Εὐμενίδες)—also shows how the Greek gods interacted with the characters and influenced their decisions pertaining to events and disputes.[1] The only extant example of an ancient Greek theatre trilogy, the Oresteia won first prize at the Dionysia festival in 458 BC. The principal themes of the trilogy include the contrast between revenge and justice, as well as the transition from personal vendetta to organized litigation.[2] Oresteia originally included a satyr play, Proteus (Πρωτεύς), following the tragic trilogy, but all except a single line of Proteus has been lost.

| Oresteia | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) SNG Drama Ljubljana performs an adaptation of The Oresteia, in 1968 | |

| Written by | Aeschylus |

| Original language | Greek |

| Genre | tragedy |

Agamemnon

| Agamemnon | |

|---|---|

The murder of Agamemnon, from an 1879 illustration from Stories from the Greek Tragedians by Alfred Church | |

| Written by | Aeschylus |

| Chorus | Elders of Argos |

| Characters | Watchman Clytemnestra Herald Agamemnon Messenger Cassandra Aegisthus |

| Mute | Soldiers Servants |

| Setting | Argos, before the royal palace |

Agamemnon (Ἀγαμέμνων, Agamémnōn) is the first of the three plays within the Oresteia trilogy. It details the homecoming of Agamemnon, King of Mycenae, from the Trojan War. After ten years of warfare, Troy had fallen and all of Greece could lay claim to victory. Waiting at home for Agamemnon is his wife, Queen Clytemnestra, who has been planning his murder. She desires his death to avenge the sacrifice of her daughter Iphigenia, to exterminate the only thing hindering her from commandeering the crown, and to finally be able to publicly embrace her long-time lover Aegisthus.[3]

The play opens to a watchman looking down and over the sea, reporting that he has been lying restless "like a dog" for a year, waiting to see some sort of signal confirming a Greek victory in Troy. He laments the fortunes of the house, but promises to keep silent: "A huge ox has stepped onto my tongue." The watchman sees a light far off in the distance—a bonfire signaling Troy's fall—and is overjoyed at the victory and hopes for the hasty return of his King, as the house has "wallowed" in his absence. Clytemnestra is introduced to the audience and she declares that there will be celebrations and sacrifices throughout the city as Agamemnon and his army return.

Upon the return of Agamemnon, his wife laments in full view of Argos how horrible the wait for her husband, and King, has been. After her soliloquy, Clytemnestra pleads with and persuades Agamemnon to walk on the robes laid out for him. This is a very ominous moment in the play as loyalties and motives are questioned. The King's new concubine, Cassandra, is now introduced and this immediately spawns hatred from the queen, Clytemnestra. Cassandra is ordered out of her chariot and to the altar where, once she is alone, she is heard crying out insane prophecies to Apollo about the death of Agamemnon and her own shared fate.

Inside the house a cry is heard; Agamemnon has been stabbed in the bathtub. The chorus separate from one another and ramble to themselves, proving their cowardice, when another final cry is heard. When the doors are finally opened, Clytemnestra is seen standing over the dead bodies of Agamemnon and Cassandra. Clytemnestra describes the murder in detail to the chorus, showing no sign of remorse or regret. Suddenly the exiled lover of Clytemnestra, Aegisthus, bursts into the palace to take his place next to her. Aegisthus proudly states that he devised the plan to murder Agamemnon and claim revenge for his father (the father of Aegisthus, Thyestes, was tricked into eating two of his sons by his brother Atreus, the father of Agamemnon). Clytemnestra claims that she and Aegisthus now have all the power and they re-enter the palace with the doors closing behind them.[4]

The Libation Bearers

| The Libation Bearers | |

|---|---|

Orestes, Electra and Hermes in front of Agamemnon's tomb by Choephoroi Painter | |

| Written by | Aeschylus |

| Chorus | Slave women |

| Characters |

|

| Setting |

|

In The Libation Bearers (Χοηφόροι, Choēphóroi)—the second play of Aeschylus' Oresteia trilogy—many years after the murder of Agamemnon, his son Orestes returns to Argos with his cousin Pylades to exact vengeance on Clytemnestra, as an order from Apollo, for killing Agamemnon.[5] Upon arriving, Orestes reunites with his sister Electra at Agamemnon's grave, while she was there bringing libations to Agamemnon in an attempt to stop Clytemnestra's bad dreams.[6] Shortly after the reunion, both Orestes and Electra, influenced by the Chorus, come up with a plan to kill both Clytemnestra and Aegisthus.[7]

Orestes then heads to the palace door where he is unexpectedly greeted by Clytemnestra. In his response to her he pretends he is a stranger and tells Clytemnestra that he (Orestes) is dead, causing her to send for Aegisthus. Unrecognized, Orestes is then able to enter the palace where he then kills Aegisthus, who was without a guard due to the intervention of the Chorus in relaying Clytemnestra's message.[8] Clytemnestra then enters the room. Orestes hesitates to kill her, but Pylades reminds him of Apollo's orders, and he eventually follows through.[6] Consequently, after committing the matricide, Orestes is now the target of the Furies' merciless wrath and has no choice but to flee from the palace.[8]

The Eumenides

| The Eumenides | |

|---|---|

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp) Orestes Pursued by the Furies by William-Adolphe Bouguereau | |

| Written by | Aeschylus |

| Chorus | The Erinyes |

| Characters | |

| Setting | before the temple of Apollo at Delphi and in Athens |

The final play of the Oresteia, called The Eumenides (Εὐμενίδες, Eumenídes), illustrates how the sequence of events in the trilogy ends up in the development of social order or a proper judicial system in Athenian society.[1] In this play, Orestes is hunted and tormented by the Furies, a trio of goddesses known to be the instruments of justice, who are also referred to as the "Gracious Ones" (Eumenides). They relentlessly pursue Orestes for the killing of his mother.[9] Through the intervention of Apollo, Orestes is able to escape them for a brief moment while they are asleep and head to Athens under the protection of Hermes. Seeing the Furies asleep, Clytemnestra's ghost comes to wake them up to obtain justice on her son Orestes for killing her.[10]

After waking up, the Furies hunt Orestes again and when they find him, Orestes pleads to the goddess Athena for help. She responds by setting up a trial for him in Athens on the Areopagus. This trial is made up of a group of twelve Athenian citizens and is supervised by Athena. Here Orestes is used as a trial dummy by Athena to set-up the first courtroom trial. He is also the object of the Furies, Apollo, and Athena.[1] After the trial comes to an end, the votes are tied. Athena casts the deciding vote and determines that Orestes will not be killed.[11] This does not sit well with the Furies but Athena eventually persuades them to accept the decision; instead of violently retaliating against wrongdoers, become a constructive force of vigilance in Athens. She then changes their names from the Furies to "the Eumenides" which means "the Gracious Ones".[12] Athena then ultimately rules that all trials must henceforth be settled in court rather than being carried out personally.[12]

Proteus

Proteus (Πρωτεύς, Prōteus), the satyr play which originally followed the first three plays of The Oresteia, is lost except for a two-line fragment preserved by Athenaeus. It is widely believed to have been based on the story told in Book IV of Homer's Odyssey, where Menelaus, Agamemnon's brother, tries to return home from Troy and finds himself on an island off Egypt, "whither he seems to have been carried by the storm described in Agam.674".[13] The title character, "the deathless Egyptian Proteus", the Old Man of the Sea, is described in Homer as having been visited by Menelaus seeking to learn his future. Proteus tells Menelaus of the death of Agamemnon at the hands of Aegisthus and the fates of Ajax the Lesser and Odysseus at sea. Proteus is compelled to tell Menelaus how to reach home from the island of Pharos. "The satyrs who may have found themselves on the island as a result of shipwreck . . . perhaps gave assistance to Menelaus and escaped with him, though he may have had difficulty in ensuring that they keep their hands off Helen".[14] The only extant fragment that has been definitively attributed to Proteus was translated by Herbert Weir Smyth as "A wretched piteous dove, in quest of food, dashed amid the winnowing-fans, its breast broken in twain."[15] In 2002, Theatre Kingston mounted a production of The Oresteia and included a new reconstruction of Proteus based on the episode in The Odyssey and loosely arranged according to the structure of extant satyr plays.

Analysis of themes

Justice through retaliation

Retaliation is seen in the Oresteia as a slippery slope, occurring after the actions of one character to another. In the first play Agamemnon, it is mentioned how to shift the wind for his voyage to Troy, Agamemnon had to sacrifice his innocent daughter Iphigenia.[16] This then caused Clytemnestra pain and eventually anger which resulted in her plotting revenge on Agamemnon. She found a new lover Aegisthus and when Agamemnon returned to Argos from the Trojan War, Clytemnestra killed him by stabbing him in the bathtub and would eventually inherit his throne.[2] The death of Agamemnon thus sparks anger in Orestes and Electra and this causes them to plot the death of their mother Clytemnestra in the next play Libation Bearers, which would be considered matricide. Through much pressure from Electra and his cousin Pylades, Orestes eventually kills his mother Clytemnestra and her lover Aegisthus in "The Libation Bearers".[16] Now after committing the matricide, Orestes is being hunted down by the Furies in the third play "The Eumenides", who wish to exact vengeance on him for this crime. And even after he gets away from them Clytemnestra's spirit comes back to rally them again so that they can kill Orestes and obtain vengeance for her.[16] However this cycle of non-stop retaliation comes to a stop near the end of The Eumenides when Athena decides to introduce a new legal system for dealing out justice.[2]

Justice through the law

This part of the theme of 'justice' in The Oresteia is seen really only in The Eumenides, however its presence still marks the shift in themes. After Orestes begged Athena for deliverance from 'the Erinyes,' she granted him his request in the form of a trial.[1] It is important that Athena did not just forgive Orestes and forbid the Furies from chasing him, she intended to put him to a trial and find a just answer to the question regarding his innocence. This is the first example of proper litigation in the trilogy and illuminates the change from emotional retaliation to civilized decisions regarding alleged crimes.[17] Instead of allowing the Furies to torture Orestes, she decided that she would have both the Furies and Orestes plead their case before she decided on the verdict. In addition, Athena set up the ground rules for how the verdict would be decided so that everything would be dealt with fairly. By Athena creating this blueprint the future of revenge-killings and the merciless hunting of the Furies would be eliminated from Greece. Once the trial concluded, Athena proclaimed the innocence of Orestes and he was set free from the Furies. The cycle of murder and revenge had come to an end while the foundation for future litigation had been laid.[11] Aeschylus, through his jury trial, was able to create and maintain a social commentary about the limitations of revenge crimes and reiterate the importance of trials.[18] The Oresteia, as a whole, stands as a representation of the evolution of justice in Ancient Greece.[19]

Revenge

The theme of revenge plays a large role in the Oresteia. It is easily seen as a principal motivator of the actions of almost all of the characters. It all starts in Agamemnon with Clytemnestra, who murders her husband, Agamemnon, in order to obtain vengeance for his sacrificing of their daughter, Iphigenia. The death of Cassandra, the princess of Troy, taken captive by Agamemnon in order to fill a place as a concubine, can also be seen as an act of revenge for taking another woman as well as the life of Iphigenia. Later on, in The Libation Bearers, Orestes and Electra, siblings as well as the other children of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra, plot to kill their mother and succeed in doing so due to their desire to avenge their father's death. The Eumenides is the last play in which the Furies, who are in fact the goddesses of vengeance, seek to take revenge on Orestes for the murder of his mother. It is also in this part of the trilogy that it is discovered that the god Apollo played a part in the act of vengeance toward Clytemnestra through Orestes. The cycle of revenge seems to be broken when Orestes is not killed by the Furies, but is instead allowed to be set free and deemed innocent by the goddess Athena. The entirety of the play's plot depends on the theme of revenge, as it is the cause of almost all of the effects within the play.

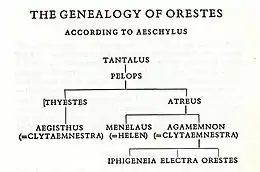

Relation to the Curse of the House of Atreus

The House of Atreus began with Tantalus, son of Zeus, who murdered his son, Pelops, and attempted to feed him to the gods. The gods, however, were not tricked and banished Tantalus to the Underworld and brought his son back to life. Later in life Pelops and his family line were cursed by Myrtilus, a son of Hermes, catalyzing the curse of the House of Atreus. Pelops had two children, Atreus and Thyestes, who are said to have killed their half-brother Chrysippus, and were therefore banished.

Thyestes and Aerope, Atreus’ wife, were found out to be having an affair, and in an act of vengeance, Atreus murdered his brother's sons, cooked them, and then fed them to Thyestes. Thyestes had a son with his daughter and named him Aegisthus, who went on to kill Atreus.

Atreus’ children were Agamemnon, Menelaus, and Anaxibia. Leading up to here, we can see that the curse of the House of Atreus was one forged from murder, incest and deceit, and continued in this way for generations through the family line. To put it simply, the curse demands blood for blood, a never ending cycle of murder within the family.

Those who join the family seem to play a part in the curse as well, as seen in Clytemnestra when she murders her husband Agamemnon, in revenge for sacrificing their daughter, Iphigenia.[20] Orestes, goaded by his sister Electra, murders Clytemnestra in order to exact revenge for her killing his father.

Orestes is said to be the end of the curse of the House of Atreus. The curse holds a major part in the Oresteia and is mentioned in it multiple times, showing that many of the characters are very aware of the curse's existence. Aeschylus was able to use the curse in his play as an ideal formulation of tragedy in his writing.

Contemporary background

Some scholars believe that the trilogy is influenced by contemporary political developments in Athens. A few years previously, legislation sponsored by the democratic reformer Ephialtes had stripped the court of the Areopagus, hitherto one of the most powerful vehicles of upper-class political power, of all of its functions except some minor religious duties and the authority to try homicide cases; by having his story being resolved by a judgement of the Areopagus, Aeschylus may be expressing his approval of this reform. It may also be significant that Aeschylus makes Agamemnon lord of Argos, where Homer puts his house, instead of his nearby capitol Mycenae, since about this time Athens had entered into an alliance with Argos.[21]

Adaptations

Key British productions

In 1981, Sir Peter Hall directed Tony Harrison's adaptation of the trilogy in masks in London's Royal National Theatre, with music by Harrison Birtwistle and stage design by Jocelyn Herbert.[22][23][24] In 1999, Katie Mitchell followed him at the same venue (though in the Cottesloe Theatre, where Hall had directed in the Olivier Theatre) with a production which used Ted Hughes' translation.[25] In 2015, Robert Icke's production of his own adaptation was a sold out hit at the Almeida Theatre and was transferred that same year to the West End's Trafalgar Studios.[26] Two other productions happened in the UK that year, in Manchester and at Shakespeare's Globe.[27] The following year, in 2016, playwright Zinnie Harris premiered her adaptation, This Restless House, at the Citizen's Theatre to five-star critical acclaim.[28]

Other adaptations

- 1895: Composer Sergei Taneyev adapted the trilogy into his own operatic trilogy of the same name, which was premiered in 1895.

- 1965-66: Composer Iannis Xenakis adapted vocal work for chorus and 12 instruments.

- 1967: Composer Felix Werder adapted Agamemnon as an opera.[29]

- 1969: The Spaghetti Western The Forgotten Pistolero, is based on the myth and set in Mexico following the Second Mexican Empire. Ferdinando Baldi, who directed the film, was also a professor of classical literature who specialized in Greek tragedy.[30][31][32][33]

- 1974: Rush Rehm's translation of the trilogy was staged at The Pram Factory in Melbourne.

- 2008: Theatre professor Ethan Sinnott directed an ASL adaptation of Agamemnon.[34]

- 2008: Dominic Allen and James Wilkes, The Oresteia, for Belt Up Theatre Company.[35]

- 2009: Anne Carson's An Oresteia, an adaptation featuring episodes from the Oresteia from three different playwrights: Aeschylus' Agamemnon, Sophocles' Electra, and Euripides' Orestes.

- 2009: Yael Farber's Molora, a South African adaptation of the Oresteia.

- 2019: Playwright Ellen McLaughlin and director Michael Khan's The Oresteia, premiered on April 30, 2019 at the Shakespeare Theatre Company, Washington, DC. The adaptation was shown as a digital production by Theater for a New Audience in New York City during the COVID-19 Pandemic and was directed by Andrew Watkins.[36][37]

Translations

- Thomas Medwin and Percy Bysshe Shelley, 1832–1834 – verse (Pagan Press reprint 2011)

- Anna Swanwick, 1886 – verse: full text

- Robert Browning, 1889 – verse: Agamemnon

- Arthur S. Way, 1906 – verse

- John Stuart Blackie, 1906 – verse

- Edmund Doidge Anderson Morshead, 1909 – verse: full text

- Herbert Weir Smyth, Aeschylus, Loeb Classical Library, 2 vols. Greek text with facing translations, 1922 – prose Agamemnon Libation Bearers Eumenides

- Gilbert Murray, 1925 – verse Agamemnon, Libation Bearers

- Louis MacNeice, 1936 – verse Agamemnon

- Edith Hamilton, 1937, Three Greek Plays: Prometheus Bound, Agamemnon, The Trojan Women

- Richmond Lattimore, 1953 – "verse"

- F. L. Lucas, 1954 – verse Agamemnon

- Robert A. Johnston, 1955 – verse, an "acting version"

- Philip Vellacott, 1956 – verse

- Paul Roche, 1963 – verse

- Peter Arnott, 1964 – verse

- George Thomson, 1965 – verse

- John Lewin, 1966 (University of Minnesota Press)

- Howard Rubenstein, 1965 – verse Agamemnon

- Hugh Lloyd-Jones, 1970 – verse

- Rush Rehm, 1978 – verse, for the stage

- Robert Fagles, 1975 – verse

- Robert Lowell, 1977 – verse

- Tony Harrison, 1981 – verse

- David Grene and Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty, 1989 – verse

- Peter Meineck, 1998 – verse

- Ted Hughes, 1999 – verse

- Ian C. Johnston, 2002 – verse: full text

- George Theodoridis, Agamemnon, Choephori, Eumenides 2005–2007 – prose

- Alan Sommerstein, Aeschylus, Loeb Classical Library, 3 vols. Greek text with facing translations, 2008

- Peter Arcese, 2010 – Agamemnon, in syllabic verse

- Sarah Ruden , 2016 – verse

- David Mulroy, 2018 – verse

- Oliver Taplin, 2018 – verse

- Jeffrey Scott Bernstein and Tom Phillips (illustrator), 2020 – verse

See also

- The Oresteia in the arts and popular culture

- Mourning Becomes Electra – a modernized version of the story by Eugene O'Neill, who shifts the action to the American Civil War

- The Flies – an adaptation of the Libation-Bearers by Jean-Paul Sartre, which focuses on human freedom

- Live by the sword, die by the sword – a line from the trilogy

Citations

- Porter, David (2005). "Aeschylus' "Eumenides": Some Contrapuntal Lines". The American Journal of Philology. 126 (3): 301–331. doi:10.1353/ajp.2005.0044. JSTOR 3804934. S2CID 170134271.

- Euben, J. Peter (March 1982). "Justice and the Oresteia". The American Political Science Review. 76 (1): 22–33. doi:10.2307/1960439. JSTOR 1960439.

- Burke, Kenneth (July–September 1952). "Form and Persecution in the Oresteia". The Sewanee Review. 60 (3): 377–396. JSTOR 27538150.

- Aeschylus (1975). The Oresteia. New York, New York: Penguin Group. pp. 103–172. ISBN 978-0-14-044333-2.

- Vellacot, Philip (1984). "Aeschylus' Orestes". The Classical World. The Johns Hopkins University Press on behalf of the Classical Association of the Atlantic States. 77 (3): 145–157. doi:10.2307/4349540. JSTOR 4349540.

- O'Neill, K. (1998). "Aeschylus, Homer, and the Serpent at the Breast". Phoenix. Classical Association of Canada. 52 (3/4): 216–229. doi:10.2307/1088668. JSTOR 1088668.

- Kells, J. H. (1966). "More Notes on Euripides' Electra". The Classical Quarterly. Cambridge University Press on behalf of The Classical Association. 16 (1): 51–54. doi:10.1017/S0009838800003359. JSTOR 637530. S2CID 170813768.

- H., R. (1928). "Orestes Sarcophagus and Greek Accessions". The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Cleveland Museum of Art. 15 (4): 90–87. JSTOR 25137120.

- Henrichs, Albert (1994). "Anonymity and Polarity: Unknown Gods and Nameless Altars at the Areopagos". Illinois Classical Studies. University of Illinois Press. 19: 27–58. JSTOR 23065418.

- Trousdell, Richard (2008). "Tragedy and Transformation: The Oresteia of Aeschylus". Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche. C.G. Jung Institute of San Francisco. 2 (3): 5–38. doi:10.1525/jung.2008.2.3.5. JSTOR 10.1525/jung.2008.2.3.5. S2CID 170372385.

- Hester, D. A. (1981). "The Casting Vote". The American Journal of Philology. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 102 (3): 265–274. doi:10.2307/294130. JSTOR 294130.

- Mace, Sarah (2004). "Why the Oresteia's Sleeping Dead Won't Lie, Part II: "Choephoroi" and "Eumenides"". The Classical Journal. The Classical Association of the Middle West and South, Inc. (CAMWS). 100 (1): 39–60. JSTOR 4133005.

- Smyth, H.W. (1930). Aeschylus: Agamemnon, Libation-Bearers, Eumenides, Fragments. Harvard University Press. p. 455. ISBN 0-674-99161-3.

- Alan Sommerstein: Aeschylus Fragments, Loeb Classical Library, 2008

- Smyth, H. W. (1930). Aeschylus: Agamemnon, Libation-Bearers, Eumenides, Fragments. Harvard University Press. p. 455. ISBN 0-674-99161-3.

- Scott, William (1966). "Wind Imagery in the Oresteia". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 97: 459–471. doi:10.2307/2936026. JSTOR 2936026.

- Burke, Kenneth (1952). "Form and Persecution in the Oresteia". The Sewanee Review. 20: 377–396.

- Raaflaub, Kurt (1974). "Conceptualizing and Theorizing Peace in Ancient Greece". Transactions of the American Philological Association. 129 (2): 225–250. JSTOR 40651971.

- Trousdell, Richard (2008). "Tragedy and Transformation: The Oresteia of Aeschylus". Jung Journal: Culture and Psyche. 2: 5–38. doi:10.1525/jung.2008.2.3.5. S2CID 170372385.

- Zeitlin, Froma I. (1966-01-01). "Postscript to Sacrificial Imagery in the Oresteia (Ag. 1235–37)". Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association. 97: 645–653. doi:10.2307/2936034. JSTOR 2936034.

- Bury, J. B.; Meiggs, Russell (1956). A history of Greece to the death of Alexander the Great, 3rd edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 347–348, 352.

- "Sir Peter Hall | National Theatre". www.nationaltheatre.org.uk. 12 April 2016. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- "About 'The Oresteia' Production". jocelynherbert.org. Retrieved 2021-02-28.

- Nightingale, Benedict (1981-12-20). "'ORESTEIA'". New York Times.

- "An inexhaustible masterpiece is transformed into a glib anti-war morality play". Daily Telegraph. 1999-12-03. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 2016-02-26. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- Higgins, Charlotte (2015-07-30). "Ancient Greek tragedy Oresteia receives surprise West End transfer". The Guardian. Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- Higgins, Charlotte (2015-07-30). "Ancient Greek tragedy Oresteia receives surprise West End transfer". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-08-13.

- "This Restless House five star review Zinnie Harris". The Guardian. 3 May 2016.

-

- Thérèse Radic. "Agamemnon", Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed October 15, 2015), (subscription access)

- Silvia Dionisio. "Terror Express".

- "Fistful of Pasta: Texas Adios".

- "The Forgotten Pistolero Review". The Spaghetti Western Database.

- "The Forgotten Pistolero Review by Korano". The Spaghetti Western Database.

- "SCENOGRAPHY". home. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- "Theatre review: The Oresteia at York Theatre Royal Studio". British Theatre Guide. Retrieved 2020-10-08.

- "The Oresteia 18-19". Shakespeare Theatre Company. Retrieved 2020-10-09.

- "THE ORESTEIA streaming free June 25–2". 9 June 2021.

General references

- Collard, Christopher (2002). Introduction to and translation of Oresteia. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-283281-6.

- Widzisz, Marcel (2012). Chronos on the Threshold: Time, Ritual, and Agency in the Oresteia. Lexington Press. ISBN 978-0-7391-7045-8.

- MacLeod, C. W. (1982). "Politics and the Oresteia". The Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 102. doi:10.2307/631132. JSTOR 631132. pp. 124–144.

Further reading

- Barbara Goward (2005). Aeschylus: Agamemnon. Duckworth Companions to Greek and Roman Tragedy. London: Duckworth. ISBN 978-0-7156-3385-4.

External links

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ἀγαμέμνων

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ἀγαμέμνων Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Χοηφόροι

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Χοηφόροι Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Εὐμενίδες

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Εὐμενίδες- Oresteia at Theatricalia.com

Oresteia public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Oresteia public domain audiobook at LibriVox- See the triumphant ending of The Oresteia. MacMillan Films staging 2014. 5 minutes.

- BBC audio file. The Oresteia discussion on the BBC Radio 4 programme In Our Time. 45 minutes.

- La Tragedie d'Oreste et Electre: Album by British band Cranes which is a musical adaptation of Jean-Paul Sartre's The Flies.

- Oresteia (2011): an avant-garde work inspired by Aeschylus' trilogy, written and directed by Jonathan Vandenberg.