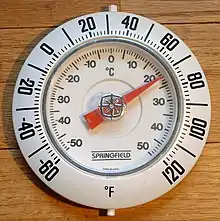

Thermometer

A thermometer is a device that measures temperature or a temperature gradient (the degree of hotness or coldness of an object). A thermometer has two important elements: (1) a temperature sensor (e.g. the bulb of a mercury-in-glass thermometer or the pyrometric sensor in an infrared thermometer) in which some change occurs with a change in temperature; and (2) some means of converting this change into a numerical value (e.g. the visible scale that is marked on a mercury-in-glass thermometer or the digital readout on an infrared model). Thermometers are widely used in technology and industry to monitor processes, in meteorology, in medicine, and in scientific research.

History

While an individual thermometer is able to measure degrees of hotness, the readings on two thermometers cannot be compared unless they conform to an agreed scale. Today there is an absolute thermodynamic temperature scale. Internationally agreed temperature scales are designed to approximate this closely, based on fixed points and interpolating thermometers. The most recent official temperature scale is the International Temperature Scale of 1990. It extends from 0.65 K (−272.5 °C; −458.5 °F) to approximately 1,358 K (1,085 °C; 1,985 °F).

Early developments

Various authors have credited the invention of the thermometer to Hero of Alexandria. The thermometer was not a single invention, however, but a development. Hero of Alexandria (10–70 AD) knew of the principle that certain substances, notably air, expand and contract and described a demonstration in which a closed tube partially filled with air had its end in a container of water.[2] The expansion and contraction of the air caused the position of the water/air interface to move along the tube.

Such a mechanism was later used to show the hotness and coldness of the air with a tube in which the water level is controlled by the expansion and contraction of the gas. These devices were developed by several European scientists in the 16th and 17th centuries, notably Galileo Galilei[3] and Santorio Santorio.[4] As a result, devices were shown to produce this effect reliably, and the term thermoscope was adopted because it reflected the changes in sensible heat (the modern concept of temperature was yet to arise).[3] The difference between a thermoscope and a thermometer is that the latter has a scale.[5] Though Galileo is often said to be the inventor of the thermometer, there is no surviving document that he actually produced any such instrument.

The first clear diagram of a thermoscope was published in 1617 by Giuseppe Biancani (1566 – 1624); the first showing a scale and thus constituting a thermometer was by Santorio Santorio in 1625.[4] This was a vertical tube, closed by a bulb of air at the top, with the lower end opening into a vessel of water. The water level in the tube is controlled by the expansion and contraction of the air, so it is what we would now call an air thermometer.[6]

The word thermometer (in its French form) first appeared in 1624 in La Récréation Mathématique by Jean Leurechon, who describes one with a scale of 8 degrees.[7] The word comes from the Greek words θερμός, thermos, meaning "hot" and μέτρον, metron, meaning "measure".

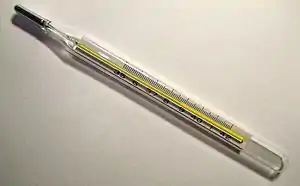

The above instruments suffered from the disadvantage that they were also barometers, i.e. sensitive to air pressure. In 1629, Joseph Solomon Delmedigo, a student of Galileo and Santorio in Padua, published what is apparently the first description and illustration of a sealed liquid-in-glass thermometer. It is described as having a bulb at the bottom of a sealed tube partially filled with brandy. The tube had a numbered scale. Delmedigo did not claim to have invented this instrument. Nor did he name anyone else as its inventor.[8] In about 1654, Ferdinando II de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany (1610–1670) did produce such an instrument, the first modern-style thermometer, dependent on the expansion of a liquid and independent of air pressure.[7] Many other scientists experimented with various liquids and designs of thermometer.

However, each inventor and each thermometer was unique — there was no standard scale. Early attempts at standardization added a single reference point such as the freezing point of water. The use of two references for graduating the thermometer is said to have been introduced by Joachim Dalence[9] in 1668 although Christiaan Huygens (1629–1695) in 1665 had already suggested the use of graduations based on the melting and boiling points of water as standards[10] and, in 1694, Carlo Renaldini (1615–1698) proposed using them as fixed points along a universal scale. In 1701, Isaac Newton (1642–1726/27) proposed a scale of 12 degrees between the melting point of ice and body temperature.

Era of precision thermometry

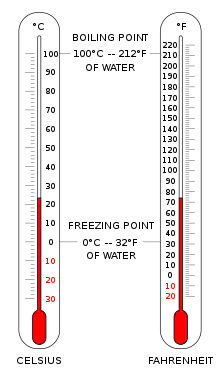

In 1714, scientist and inventor Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit invented a reliable thermometer, using mercury instead of alcohol and water mixtures. In 1724, he proposed a temperature scale which now (slightly adjusted) bears his name. In 1742, Anders Celsius (1701–1744) proposed a scale with zero at the boiling point and 100 degrees at the freezing point of water,[11] though the scale which now bears his name has them the other way around.[12] French entomologist René Antoine Ferchault de Réaumur invented an alcohol thermometer and, temperature scale in 1730, that ultimately proved to be less reliable than Fahrenheit's mercury thermometer.

The first physician to use thermometer measurements in clinical practice was Herman Boerhaave (1668–1738).[13] In 1866, Sir Thomas Clifford Allbutt (1836–1925) invented a clinical thermometer that produced a body temperature reading in five minutes as opposed to twenty.[14] In 1999, Dr. Francesco Pompei of the Exergen Corporation introduced the world's first temporal artery thermometer, a non-invasive temperature sensor which scans the forehead in about two seconds and provides a medically accurate body temperature.[15][16]

Registering

Traditional thermometers were all non-registering thermometers. That is, the thermometer did not hold the temperature reading after it was moved to a place with a different temperature. Determining the temperature of a pot of hot liquid required the user to leave the thermometer in the hot liquid until after reading it. If the non-registering thermometer was removed from the hot liquid, then the temperature indicated on the thermometer would immediately begin changing to reflect the temperature of its new conditions (in this case, the air temperature). Registering thermometers are designed to hold the temperature indefinitely, so that the thermometer can be removed and read at a later time or in a more convenient place. Mechanical registering thermometers hold either the highest or lowest temperature recorded until manually re-set, e.g., by shaking down a mercury-in-glass thermometer, or until an even more extreme temperature is experienced. Electronic registering thermometers may be designed to remember the highest or lowest temperature, or to remember whatever temperature was present at a specified point in time.

Thermometers increasingly use electronic means to provide a digital display or input to a computer.

Physical principles of thermometry

Thermometers may be described as empirical or absolute. Absolute thermometers are calibrated numerically by the thermodynamic absolute temperature scale. Empirical thermometers are not in general necessarily in exact agreement with absolute thermometers as to their numerical scale readings, but to qualify as thermometers at all they must agree with absolute thermometers and with each other in the following way: given any two bodies isolated in their separate respective thermodynamic equilibrium states, all thermometers agree as to which of the two has the higher temperature, or that the two have equal temperatures.[17] For any two empirical thermometers, this does not require that the relation between their numerical scale readings be linear, but it does require that relation to be strictly monotonic.[18] This is a fundamental character of temperature and thermometers.[19][20][21]

As it is customarily stated in textbooks, taken alone, the so-called "zeroth law of thermodynamics" fails to deliver this information, but the statement of the zeroth law of thermodynamics by James Serrin in 1977, though rather mathematically abstract, is more informative for thermometry: "Zeroth Law – There exists a topological line which serves as a coordinate manifold of material behaviour. The points of the manifold are called 'hotness levels', and is called the 'universal hotness manifold'."[22] To this information there needs to be added a sense of greater hotness; this sense can be had, independently of calorimetry, of thermodynamics, and of properties of particular materials, from Wien's displacement law of thermal radiation: the temperature of a bath of thermal radiation is proportional, by a universal constant, to the frequency of the maximum of its frequency spectrum; this frequency is always positive, but can have values that tend to zero. Another way of identifying hotter as opposed to colder conditions is supplied by Planck's principle, that when a process of isochoric adiabatic work is the sole means of change of internal energy of a closed system, the final state of the system is never colder than the initial state; except for phase changes with latent heat, it is hotter than the initial state.[23][24][25]

There are several principles on which empirical thermometers are built, as listed in the section of this article entitled "Primary and secondary thermometers". Several such principles are essentially based on the constitutive relation between the state of a suitably selected particular material and its temperature. Only some materials are suitable for this purpose, and they may be considered as "thermometric materials". Radiometric thermometry, in contrast, can be only slightly dependent on the constitutive relations of materials. In a sense then, radiometric thermometry might be thought of as "universal". This is because it rests mainly on a universality character of thermodynamic equilibrium, that it has the universal property of producing blackbody radiation.

Thermometric materials

There are various kinds of empirical thermometer based on material properties.

Many empirical thermometers rely on the constitutive relation between pressure, volume and temperature of their thermometric material. For example, mercury expands when heated.

If it is used for its relation between pressure and volume and temperature, a thermometric material must have three properties:

(1) Its heating and cooling must be rapid. That is to say, when a quantity of heat enters or leaves a body of the material, the material must expand or contract to its final volume or reach its final pressure and must reach its final temperature with practically no delay; some of the heat that enters can be considered to change the volume of the body at constant temperature, and is called the latent heat of expansion at constant temperature; and the rest of it can be considered to change the temperature of the body at constant volume, and is called the specific heat at constant volume. Some materials do not have this property, and take some time to distribute the heat between temperature and volume change.[26]

(2) Its heating and cooling must be reversible. That is to say, the material must be able to be heated and cooled indefinitely often by the same increment and decrement of heat, and still return to its original pressure, volume and temperature every time. Some plastics do not have this property;[27]

(3) Its heating and cooling must be monotonic.[18][28] That is to say, throughout the range of temperatures for which it is intended to work,

- (a) at a given fixed pressure,

- either (i) the volume increases when the temperature increases, or else (ii) the volume decreases when the temperature increases;

- but not (i) for some temperatures and (ii) for others; or

- (b) at a given fixed volume,

- either (i) the pressure increases when the temperature increases, or else (ii) the pressure decreases when the temperature increases;

- but not (i) for some temperatures and (ii) for others.

At temperatures around about 4 °C, water does not have the property (3), and is said to behave anomalously in this respect; thus water cannot be used as a material for this kind of thermometry for temperature ranges near 4 °C.[20][29][30][31][32]

Gases, on the other hand, all have the properties (1), (2), and (3)(a)(α) and (3)(b)(α). Consequently, they are suitable thermometric materials, and that is why they were important in the development of thermometry.[33]

Constant volume thermometry

According to Preston (1894/1904), Regnault found constant pressure air thermometers unsatisfactory, because they needed troublesome corrections. He therefore built a constant volume air thermometer.[34] Constant volume thermometers do not provide a way to avoid the problem of anomalous behaviour like that of water at approximately 4 °C.[32]

Radiometric thermometry

Planck's law very accurately quantitatively describes the power spectral density of electromagnetic radiation, inside a rigid walled cavity in a body made of material that is completely opaque and poorly reflective, when it has reached thermodynamic equilibrium, as a function of absolute thermodynamic temperature alone. A small enough hole in the wall of the cavity emits near enough blackbody radiation of which the spectral radiance can be precisely measured. The walls of the cavity, provided they are completely opaque and poorly reflective, can be of any material indifferently. This provides a well-reproducible absolute thermometer over a very wide range of temperatures, able to measure the absolute temperature of a body inside the cavity.

Primary and secondary thermometers

A thermometer is called primary or secondary based on how the raw physical quantity it measures is mapped to a temperature. As summarized by Kauppinen et al., "For primary thermometers the measured property of matter is known so well that temperature can be calculated without any unknown quantities. Examples of these are thermometers based on the equation of state of a gas, on the velocity of sound in a gas, on the thermal noise voltage or current of an electrical resistor, and on the angular anisotropy of gamma ray emission of certain radioactive nuclei in a magnetic field."[35]

In contrast, "Secondary thermometers are most widely used because of their convenience. Also, they are often much more sensitive than primary ones. For secondary thermometers knowledge of the measured property is not sufficient to allow direct calculation of temperature. They have to be calibrated against a primary thermometer at least at one temperature or at a number of fixed temperatures. Such fixed points, for example, triple points and superconducting transitions, occur reproducibly at the same temperature."[35]

Calibration

Thermometers can be calibrated either by comparing them with other calibrated thermometers or by checking them against known fixed points on the temperature scale. The best known of these fixed points are the melting and boiling points of pure water. (Note that the boiling point of water varies with pressure, so this must be controlled.)

The traditional way of putting a scale on a liquid-in-glass or liquid-in-metal thermometer was in three stages:

- Immerse the sensing portion in a stirred mixture of pure ice and water at atmospheric pressure and mark the point indicated when it had come to thermal equilibrium.

- Immerse the sensing portion in a steam bath at Standard atmospheric pressure and again mark the point indicated.

- Divide the distance between these marks into equal portions according to the temperature scale being used.

Other fixed points used in the past are the body temperature (of a healthy adult male) which was originally used by Fahrenheit as his upper fixed point (96 °F (35.6 °C) to be a number divisible by 12) and the lowest temperature given by a mixture of salt and ice, which was originally the definition of 0 °F (−17.8 °C).[36] (This is an example of a Frigorific mixture.) As body temperature varies, the Fahrenheit scale was later changed to use an upper fixed point of boiling water at 212 °F (100 °C).[37]

These have now been replaced by the defining points in the International Temperature Scale of 1990, though in practice the melting point of water is more commonly used than its triple point, the latter being more difficult to manage and thus restricted to critical standard measurement. Nowadays manufacturers will often use a thermostat bath or solid block where the temperature is held constant relative to a calibrated thermometer. Other thermometers to be calibrated are put into the same bath or block and allowed to come to equilibrium, then the scale marked, or any deviation from the instrument scale recorded.[38] For many modern devices calibration will be stating some value to be used in processing an electronic signal to convert it to a temperature.

Precision, accuracy, and reproducibility

The precision or resolution of a thermometer is simply to what fraction of a degree it is possible to make a reading. For high temperature work it may only be possible to measure to the nearest 10 °C or more. Clinical thermometers and many electronic thermometers are usually readable to 0.1 °C. Special instruments can give readings to one thousandth of a degree. However, this precision does not mean the reading is true or accurate, it only means that very small changes can be observed.

A thermometer calibrated to a known fixed point is accurate (i.e. gives a true reading) at that point. Most thermometers are originally calibrated to a constant-volume gas thermometer. In between fixed calibration points, interpolation is used, usually linear.[38] This may give significant differences between different types of thermometer at points far away from the fixed points. For example, the expansion of mercury in a glass thermometer is slightly different from the change in resistance of a platinum resistance thermometer, so these two will disagree slightly at around 50 °C.[39] There may be other causes due to imperfections in the instrument, e.g. in a liquid-in-glass thermometer if the capillary tube varies in diameter.[39]

For many purposes reproducibility is important. That is, does the same thermometer give the same reading for the same temperature (or do replacement or multiple thermometers give the same reading)? Reproducible temperature measurement means that comparisons are valid in scientific experiments and industrial processes are consistent. Thus if the same type of thermometer is calibrated in the same way its readings will be valid even if it is slightly inaccurate compared to the absolute scale.

An example of a reference thermometer used to check others to industrial standards would be a platinum resistance thermometer with a digital display to 0.1 °C (its precision) which has been calibrated at 5 points against national standards (−18, 0, 40, 70, 100 °C) and which is certified to an accuracy of ±0.2 °C.[40]

According to British Standards, correctly calibrated, used and maintained liquid-in-glass thermometers can achieve a measurement uncertainty of ±0.01 °C in the range 0 to 100 °C, and a larger uncertainty outside this range: ±0.05 °C up to 200 or down to −40 °C, ±0.2 °C up to 450 or down to −80 °C.[41]

Indirect methods of temperature measurement

- Thermal expansion

- Utilizing the property of thermal expansion of various phases of matter.

- Pairs of solid metals with different expansion coefficients can be used for bi-metal mechanical thermometers. Another design using this principle is Breguet's thermometer.

- Some liquids possess relatively high expansion coefficients over a useful temperature ranges thus forming the basis for an alcohol or mercury thermometer. Alternative designs using this principle are the reversing thermometer and Beckmann differential thermometer.

- As with liquids, gases can also be used to form a gas thermometer.

- Pressure

- Vapour pressure thermometer

- Density

- Galileo thermometer[42]

- Thermochromism

- Some compounds exhibit thermochromism at distinct temperature changes. Thus by tuning the phase transition temperatures for a series of substances the temperature can be quantified in discrete increments, a form of digitization. This is the basis for a liquid crystal thermometer.

- Band edge thermometry (BET)

- Band edge thermometry (BET) takes advantage of the temperature-dependence of the band gap of semiconductor materials to provide very precise optical (i.e. non-contact) temperature measurements.[43] BET systems require a specialized optical system, as well as custom data analysis software.[44][45]

- Blackbody radiation

- All objects above absolute zero emit blackbody radiation for which the spectra is directly proportional to the temperature. This property is the basis for a pyrometer or infrared thermometer and thermography. It has the advantage of remote temperature sensing; it does not require contact or even close proximity unlike most thermometers. At higher temperatures, blackbody radiation becomes visible and is described by the colour temperature. For example a glowing heating element or an approximation of a star's surface temperature.

- Fluorescence

- Phosphor thermometry

- Optical absorbance spectra

- Fiber optical thermometer

- Electrical resistance

- Resistance thermometer which use materials such as Balco alloy

- Thermistor

- Coulomb blockade thermometer

- Electrical potential

- Thermocouples are useful over a wide temperature ranges from cryogenic temperatures to over 1000°C, but typically have an error of ±0.5-1.5°C.

- Silicon bandgap temperature sensors are commonly found packaged in integrated circuits with accompanying ADC and interface such as I2C. Typically they are specified to work within about —50 to 150°C with accuracies in the ±0.25 to 1°C range but can be improved by binning.[46][47]

- Electrical resonance

- Quartz thermometer

- Nuclear magnetic resonance

- Chemical shift is temperature dependent. This property is used to calibrate the thermostat of NMR probes, usually using methanol or ethylene glycol.[48][49] This can potentially be problematic for internal standards which are usually assumed to have a defined chemical shift (e.g 0 ppm for TMS) but in fact exhibit a temperature dependence.[50]

- Magnetic susceptibility

- Above the Curie temperature, the magnetic susceptibility of a paramagnetic material exhibits an inverse temperature dependence. This phenomenon is the basis of a magnetic cryometer.[51][52]

Applications

Thermometers utilize a range of physical effects to measure temperature. Temperature sensors are used in a wide variety of scientific and engineering applications, especially measurement systems. Temperature systems are primarily either electrical or mechanical, occasionally inseparable from the system which they control (as in the case of a mercury-in-glass thermometer). Thermometers are used in roadways in cold weather climates to help determine if icing conditions exist. Indoors, thermistors are used in climate control systems such as air conditioners, freezers, heaters, refrigerators, and water heaters.[53] Galileo thermometers are used to measure indoor air temperature, due to their limited measurement range.

Such liquid crystal thermometers (which use thermochromic liquid crystals) are also used in mood rings and used to measure the temperature of water in fish tanks.

Fiber Bragg grating temperature sensors are used in nuclear power facilities to monitor reactor core temperatures and avoid the possibility of nuclear meltdowns.[54]

Nanothermometry

Nanothermometry is an emergent research field dealing with the knowledge of temperature in the sub-micrometric scale. Conventional thermometers cannot measure the temperature of an object which is smaller than a micrometre, and new methods and materials have to be used. Nanothermometry is used in such cases. Nanothermometers are classified as luminescent thermometers (if they use light to measure temperature) and non-luminescent thermometers (systems where thermometric properties are not directly related to luminescence).[55]

Cryometer

Thermometers used specifically for low temperatures.

Medical

- Ear thermometers tend to be an infrared thermometer.

- Forehead thermometer is an example of a liquid crystal thermometer.

- Rectal and oral thermometers have typically been mercury but have since largely been superseded by NTC thermistors with a digital readout.[56]

Various thermometric techniques have been used throughout history such as the Galileo thermometer to thermal imaging.[42] Medical thermometers such as mercury-in-glass thermometers, infrared thermometers, pill thermometers, and liquid crystal thermometers are used in health care settings to determine if individuals have a fever or are hypothermic.

Food and food safety

Thermometers are important in food safety, where food at temperatures within 41 and 135 °F (5 and 57 °C) can be prone to potentially harmful levels of bacterial growth after several hours which could lead to foodborne illness. This includes monitoring refrigeration temperatures and maintaining temperatures in foods being served under heat lamps or hot water baths.[53] Cooking thermometers are important for determining if a food is properly cooked. In particular meat thermometers are used to aid in cooking meat to a safe internal temperature while preventing over cooking. They are commonly found using either a bimetallic coil, or a thermocouple or thermistor with a digital readout. Candy thermometers are used to aid in achieving a specific water content in a sugar solution based on its boiling temperature.

Environmental

- Indoor-outdoor thermometer

- Heat meter uses a thermometer to measure rate of heat flow.

- Thermostats have used bimetallic strips but digital thermistors have since become popular.

Alcohol thermometers, infrared thermometers, mercury-in-glass thermometers, recording thermometers, thermistors, and Six's thermometers are used in meteorology and climatology in various levels of the atmosphere and oceans. Aircraft use thermometers and hygrometers to determine if atmospheric icing conditions exist along their flight path. These measurements are used to initialize weather forecast models. Thermometers are used in roadways in cold weather climates to help determine if icing conditions exist and indoors in climate control systems.

See also

- Automated airport weather station

- Thermodynamic instruments

- Maximum-minimum thermometer

- Wet-and-dry bulb thermometer

- Mercury-in-glass thermometer

- Infrared thermometer

- Medical thermometer

- Resistance thermometer

References

- Knake, Maria (April 2011). "The Anatomy of a Liquid-in-Glass Thermometer". AASHTO re:source, formerly AMRL (aashtoresource.org). Retrieved 4 August 2018.

For decades mercury thermometers were a mainstay in many testing laboratories. If used properly and calibrated correctly, certain types of mercury thermometers can be incredibly accurate. Mercury thermometers can be used in temperatures ranging from about -38 to 350°C. The use of a mercury-thallium mixture can extend the low-temperature usability of mercury thermometers to -56°C. (...) Nevertheless, few liquids have been found to mimic the thermometric properties of mercury in repeatability and accuracy of temperature measurement. Toxic though it may be, when it comes to LiG [Liquid-in-Glass] thermometers, mercury is still hard to beat.

- T.D. McGee (1988) Principles and Methods of Temperature Measurement ISBN 0-471-62767-4

- R.S. Doak (2005) Galileo: astronomer and physicist ISBN 0-7565-0813-4 p36

- Bigotti, Fabrizio (2018). "The Weight of the Air: Santorio's Thermometers and the Early History of Medical Quantification Reconsidered". Journal of Early Modern Studies. 7 (1): 73–103. doi:10.5840/jems2018714. ISSN 2285-6382. PMC 6407691. PMID 30854347.

- T.D. McGee (1988) Principles and Methods of Temperature Measurement page 3, ISBN 0-471-62767-4

- T.D. McGee (1988) Principles and Methods of Temperature Measurement, pages 2–4 ISBN 0-471-62767-4

- R.P. Benedict (1984) Fundamentals of Temperature, Pressure, and Flow Measurements, 3rd ed, ISBN 0-471-89383-8 page 4

- Adler, Jacob (1997). "J. S. Delmedigo and the Liquid-in-Glass Thermometer". Annals of Science. 54 (3): 293–299. doi:10.1080/00033799700200221.

- Bolton, H.C. (1900). Evolution of the thermometer 1592-1743. Easton, PA: The Chemical Publishing Company. pp. 7–8.

- Wright, William F. (2016). "Early evolution of the thermometer and application to clinical medicine". Journal of Thermal Biology. 56: 18–30. doi:10.1016/j.jtherbio.2015.12.003. PMID 26857973.

- R.P. Benedict (1984) Fundamentals of Temperature, Pressure, and Flow Measurements, 3rd ed, ISBN 0-471-89383-8 page 6

- Christin's thermometer Archived 2013-06-01 at the Wayback Machine and Linnaeus' thermometer

- Tan, S. Y.; Hu, M (2004). "Medicine in Stamps: Hermann Boerhaave (1668 - 1738): 18th Century Teacher Extraordinaire" (PDF). Singapore Medical Journal. Vol. 45, no. 1. pp. 3–5.

- Sir Thomas Clifford Allbutt, Encyclopædia Britannica

- Exergen Corporation. Exergen.com. Retrieved on 2011-03-30.

- Patents By Inventor Francesco Pompei :: Justia Patents. Patents.justia.com. Retrieved on 2011-03-30.

- Beattie, J.A., Oppenheim, I. (1979). Principles of Thermodynamics, Elsevier Scientific Publishing Company, Amsterdam, ISBN 0-444-41806-7, page 29.

- Thomsen, J.S. (1962). "A restatement of the zeroth law of thermodynamics". Am. J. Phys. 30 (4): 294–296. Bibcode:1962AmJPh..30..294T. doi:10.1119/1.1941991.

- Mach, E. (1900). Die Principien der Wärmelehre. Historisch-kritisch entwickelt, Johann Ambrosius Barth, Leipzig, section 22, pages 56-57. English translation edited by McGuinness, B. (1986), Principles of the Theory of Heat, Historically and Critically Elucidated, D. Reidel Publishing, Dordrecht, ISBN 90-277-2206-4, section 5, pp. 48–49, section 22, pages 60–61.

- Truesdell, C.A. (1980). The Tragicomical History of Thermodynamics, 1822-1854, Springer, New York, ISBN 0-387-90403-4.

- Serrin, J. (1986). Chapter 1, 'An Outline of Thermodynamical Structure', pages 3-32, especially page 6, in New Perspectives in Thermodynamics, edited by J. Serrin, Springer, Berlin, ISBN 3-540-15931-2.

- Serrin, J. (1978). The concepts of thermodynamics, in Contemporary Developments in Continuum Mechanics and Partial Differential Equations. Proceedings of the International Symposium on Continuum Mechanics and Partial Differential Equations, Rio de Janeiro, August 1977, edited by G.M. de La Penha, L.A.J. Medeiros, North-Holland, Amsterdam, ISBN 0-444-85166-6, pages 411-451.

- Planck, M. (1926). Über die Begründung des zweiten Hauptsatzes der Thermodynamik, S.-B. Preuß. Akad. Wiss. phys. math. Kl.: 453–463.

- Buchdahl, H.A. (1966). The Concepts of Classical Thermodynamics, Cambridge University Press, London, pp. 42–43.

- Lieb, E.H.; Yngvason, J. (1999). "The physics and mathematics of the second law of thermodynamics". Physics Reports. 314 (1–2): 1–96 [56]. arXiv:hep-ph/9807278. Bibcode:1999PhR...314....1L. doi:10.1016/S0370-1573(98)00128-8. S2CID 119517140.

- Truesdell, C., Bharatha, S. (1977). The Concepts and Logic of Classical Thermodynamics as a Theory of Heat Engines. Rigorously Constructed upon the Foundation Laid by S. Carnot and F. Reech, Springer, New York, ISBN 0-387-07971-8, page 20.

- Ziegler, H., (1983). An Introduction to Thermomechanics, North-Holland, Amsterdam, ISBN 0-444-86503-9.

- Landsberg, P.T. (1961). Thermodynamics with Quantum Statistical Illustrations, Interscience Publishers, New York, page 17.

- Maxwell, J.C. (1872). Theory of Heat, third edition, Longmans, Green, and Co., London, pages 232-233.

- Lewis, G.N., Randall, M. (1923/1961). Thermodynamics, second edition revised by K.S Pitzer, L. Brewer, McGraw-Hill, New York, pages 378-379.

- Thomsen, J.S.; Hartka, T.J. (1962). "Strange Carnot cycles; thermodynamics of a system with a density extremum". Am. J. Phys. 30 (1): 26–33. Bibcode:1962AmJPh..30...26T. doi:10.1119/1.1941890.

- Truesdell, C., Bharatha, S. (1977). The Concepts and Logic of Classical Thermodynamics as a Theory of Heat Engines. Rigorously Constructed upon the Foundation Laid by S. Carnot and F. Reech, Springer, New York, ISBN 0-387-07971-8, pages 9-10, 15-18, 36-37.

- Planck, M. (1897/1903). Treatise on Thermodynamics, translated by A. Ogg, Longmans, Green & Co., London.

- Preston, T. (1894/1904). The Theory of Heat, second edition, revised by J.R. Cotter, Macmillan, London, Section 92.0

- Kauppinen, J. P.; Loberg, K. T.; Manninen, A. J.; Pekola, J. P. (1998). "Coulomb blockade thermometer: Tests and instrumentation". Rev. Sci. Instrum. 69 (12): 4166–4175. Bibcode:1998RScI...69.4166K. doi:10.1063/1.1149265. S2CID 33345808.

- R.P. Benedict (1984) Fundamentals of Temperature, Pressure, and Flow Measurements, 3rd ed, ISBN 0-471-89383-8, page 5

- J. Lord (1994) Sizes ISBN 0-06-273228-5 page 293

- R.P. Benedict (1984) Fundamentals of Temperature, Pressure, and Flow Measurements, 3rd ed, ISBN 0-471-89383-8, chapter 11 "Calibration of Temperature Sensors"

- T. Duncan (1973) Advanced Physics: Materials and Mechanics (John Murray, London) ISBN 0-7195-2844-5

- Peak Sensors Reference Thermometer

- BS1041-2.1:1985 Temperature Measurement- Part 2: Expansion thermometers. Section 2.1 Guide to selection and use of liquid-in-glass thermometers

- E.F.J. Ring (January 2007). "The historical development of temperature measurement in medicine". Infrared Physics & Technology. 49 (3): 297–301. Bibcode:2007InPhT..49..297R. doi:10.1016/j.infrared.2006.06.029.

- "Band-edge thermometry". Molecular Beam Epitaxy Research Group. 2014-08-19. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- Johnson, Shane (May 1998). "In situ temperature control of molecular beam epitaxy growth using band-edge thermometry". Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B: Microelectronics and Nanometer Structures. 16 (3): 1502. Bibcode:1998JVSTB..16.1502J. doi:10.1116/1.589975. hdl:2286/R.I.27894.

- Wissman, Barry (June 2016). "The truth behind today's wafer temperature methods: Band-edge thermometry vs. emissivity-corrected pyrometry" (PDF). Retrieved December 22, 2020.

- "MCP9804: ±0.25°C Typical Accuracy Digital Temperature Sensor". Microchip. 2012. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- "Si7050/1/3/4/5-A20: I2C Temperature Sensors" (PDF). Silicon Labs. 2016. Retrieved 2017-01-03.

- Findeisen, M.; Brand, T.; Berger, S. (February 2007). "A1H-NMR thermometer suitable for cryoprobes". Magnetic Resonance in Chemistry. 45 (2): 175–178. doi:10.1002/mrc.1941. PMID 17154329. S2CID 43214876.

- Braun, Stefan Berger ;Siegmar (2004). 200 and more NMR experiments : a practical course ([3. ed.]. ed.). Weinheim: WILEY-VCH. ISBN 978-3-527-31067-8.

- Hoffman, Roy E.; Becker, Edwin D. (September 2005). "Temperature dependence of the 1H chemical shift of tetramethylsilane in chloroform, methanol, and dimethylsulfoxide". Journal of Magnetic Resonance. 176 (1): 87–98. Bibcode:2005JMagR.176...87H. doi:10.1016/j.jmr.2005.05.015. PMID 15996496.

- Krusius, Matti (2014). "Magnetic thermometer". AccessScience. doi:10.1036/1097-8542.398650.

- Sergatskov, D. A. (Oct 2003). "New Paramagnetic Susceptibility Thermometers for Fundamental Physics Measurements" (PDF). AIP Conference Proceedings (PDF). Vol. 684. pp. 1009–1014. doi:10.1063/1.1627261.

- Angela M. Fraser, Ph.D. (2006-04-24). "Food Safety: Thermometers" (PDF). North Carolina State University. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 2010-02-26.

- Fernandez, Alberto Fernandez; Gusarov, Andrei I.; Brichard, Benoît; Bodart, Serge; Lammens, Koen; Berghmans, Francis; Decréton, Marc; Mégret, Patrice; Blondel, Michel; Delchambre, Alain (2002). "Temperature monitoring of nuclear reactor cores with multiplexed fiber Bragg grating sensors". Optical Engineering. 41 (6): 1246–1254. Bibcode:2002OptEn..41.1246F. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.59.1761. doi:10.1117/1.1475739.

- Brites, Carlos D. S.; Lima, Patricia P.; Silva, Nuno J. O.; Millán, Angel; Amaral, Vitor S.; Palacio, Fernando; Carlos, Luís D. (2012). "Thermometry at the nanoscale". Nanoscale. 4 (16): 4799–829. Bibcode:2012Nanos...4.4799B. doi:10.1039/C2NR30663H. hdl:10261/76059. PMID 22763389.

- US Active 6854882, Ming-Yun Chen, "Rapid response electronic clinical thermometer", published 2005-02-15, assigned to Actherm Inc.

Further reading

- Middleton, W.E.K. (1966). A history of the thermometer and its use in meteorology. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Reprinted ed. 2002, ISBN 0-8018-7153-0.

- History of the Thermometer

- - Recent review on Thermometry at the Nanoscale

External links

- History of Temperature and Thermometry

- The Chemical Educator, Vol. 5, No. 2 (2000) The Thermometer—From The Feeling To The Instrument

- History Channel – Invention – Notable Modern Inventions and Discoveries

- About – Thermometer – Thermometers – Early History, Anders Celsius, Gabriel Fahrenheit and Thomson Kelvin.

- Thermometers and Thermometric Liquids – Mercury and Alcohol.

- The NIST Industrial Thermometer Calibration Laboratory

- Thermometry at the Nanoscale—Review