Robert F. Kennedy Bridge

The Robert F. Kennedy Bridge (RFK Bridge; formerly known and still commonly referred to as the Triborough Bridge) is a complex of bridges and elevated expressway viaducts[2] in New York City. The bridges link the boroughs of Manhattan, Queens, and the Bronx. The viaducts cross Randalls and Wards Islands, previously two islands and now joined by landfill.

Robert F. Kennedy Bridge (Triborough Bridge) | |

|---|---|

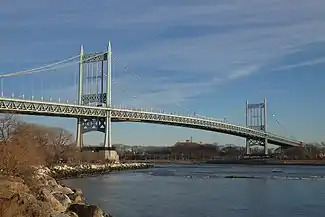

The Queens–Wards Island span of the bridge, over the East River | |

| Coordinates | 40°46′50″N 73°55′39″W |

| Carries | 8 lanes of 6 lanes of NY 900G (Manhattan span) |

| Crosses | East River, Harlem River and Bronx Kill |

| Locale | New York City, United States |

| Official name | Robert F. Kennedy Bridge |

| Other name(s) | RFK Triborough Bridge, Triboro Bridge, RFK Bridge |

| Maintained by | MTA Bridges and Tunnels |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Suspension bridge, lift bridge, truss bridge |

| Total length | 2,780 feet (850 m) (Queens span) 770 feet (230 m) (Manhattan span) 1,600 feet (490 m) (Bronx span) |

| Width | 98 feet (30 m) (Queens span) |

| Longest span | 1,380 feet (420 m) (Queens span) 310 feet (94 m) (Manhattan span) 383 feet (117 m) (Bronx span) |

| Clearance above | 14 feet 6 inches (4.42 m) (Queens/Bronx spans) 13 feet 10 inches (4.22 m) (Manhattan span) |

| Clearance below | 143 feet (44 m) (Queens span) 135 feet (41 m) (Manhattan span when raised) 55 feet (17 m) (Bronx span) |

| History | |

| Opened | July 11, 1936 |

| Statistics | |

| Daily traffic | 95,552 (Queens–Manhattan and Bronx–Manhattan, 2016)[1] 83,053 (Queens–Bronx, 2016)[1] |

| Toll | As of April 11, 2021, $10.17 (Tolls By Mail and non-New York E-ZPass); $6.55 (New York E-ZPass); $8.36 (Mid-Tier NYCSC E-Z Pass) |

| Location | |

| |

The RFK Bridge, a toll bridge, carries Interstate 278 (I-278) as well as the unsigned highway New York State Route 900G. It connects with the FDR Drive and the Harlem River Drive in Manhattan, the Bruckner Expressway (I-278) and the Major Deegan Expressway (Interstate 87) in the Bronx, and the Grand Central Parkway (I-278) and Astoria Boulevard in Queens.

The three primary bridges of the RFK Bridge complex are:[2]

- The vertical-lift bridge over Harlem River, the largest in the world, connecting Manhattan to Randalls Island

- The truss bridge over Bronx Kill, connecting Randalls Island to the Bronx

- The suspension bridge over Hell Gate (a strait of the East River), connecting Wards Island to Astoria in Queens

These three bridges are connected by an elevated highway viaduct across Randalls and Wards Islands and 14 miles (23 km) of support roads. The viaduct includes a smaller span across the former site of Little Hell Gate, which separated Randalls and Wards Islands.[2][3] Also part of the complex is a grade-separated T-interchange on Randalls Island, which sorted out traffic in a way that ensured that drivers paid a toll at only one bank of tollbooths.[4] The tollbooths have since been removed, and all tolls are collected electronically at the approaches to each bridge.

The bridge complex was designed by chief engineer Othmar H. Ammann and architect Aymar Embury II,[5] and has been called "not a bridge so much as a traffic machine, the largest ever built".[4] The American Society of Civil Engineers designated the Triborough Bridge Project as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1986.[6] The bridge is owned and operated by MTA Bridges and Tunnels (formally the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority, or TBTA), an affiliate of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority.

Description

The RFK Bridge is made of four segments. The three primary spans traverse the East River to Queens; the Harlem River to Manhattan; and Bronx Kill to the Bronx,[7] while the fourth is a T-shaped approach viaduct that leads to an interchange plaza between the three primary spans on Randalls Island. The Queens arm of the viaduct formerly crossed Little Hell Gate, a creek located between Randalls Island to the north and Wards Island to the south.[2] Excluding elevated ramps, the segments are a total of 17,710 feet (5,400 m) long, with a 13,560-foot-long (4,130 m) span between the Bronx and Queens, and a 4,150-foot-long (1,260 m) span between Manhattan and the interchange plaza.[8][9][7] In total, the bridge contains 17.5 miles (28.2 km) of roadway, including elevated ramps.[10]

The bridge was primarily designed by chief engineer Othmar H. Ammann and architect Aymar Embury II.[5] Wharton Green served as the Public Works Administration (PWA)'s resident engineer for the project.[11]

East River suspension bridge (I-278)

The East River span, a suspension bridge across the Hell Gate of the East River, connects Queens with Wards Island. It carries eight lanes of Interstate 278, four in each direction, as well as a sidewalk on the northeastern side. The span connects to Grand Central Parkway, and indirectly to the Brooklyn–Queens Expressway (I-278), in Astoria, Queens.[12] Originally it connected to the intersection of 25th Avenue and 31st Street; the former was later renamed Hoyt Avenue.[13] The suspension span was designed by chief engineer Othmar Ammann.[14] The span was originally designed to be double-decked, with eight lanes on each deck.[15][9] When the construction of the Triborough Bridge was paused in 1932 due to lack of funding, the suspension span was downsized to a single deck. There are Warren trusses on each side of the span, which stiffen the deck.[15]

The center span between the two suspension towers is 1,380 feet (421 m) long, and the side spans between the suspension towers and the anchorages are each 700 feet (213 m) long.[15] The total length of the bridge is 2,780 feet (847 m), and the deck is 98 feet (30 m) wide.[15]

At mean high water, the towers are 315 feet (96 m) tall, and there is 143 feet (44 m) of clearance under the middle of the main span.[15] The suspension towers were originally designed by Arthur I. Perry. Each tower was supposed to have two ornate arches at the top, similar to the Brooklyn Bridge, and was to have been supported by four legs: two on the outside and two in the center.[16][9] A 1932 article described that each tower would be made of 5,000 tons of material, including 3,680 tons of steel.[9] The final design of the suspension towers, by Ammann, consists of comparatively simple cross bracing supported by two legs.[16] The tops of each tower contain cast iron saddles in the Art Deco style, over which the bridge's main cables run. These are topped by 30-foot (9.1 m) decorative lanterns with red aircraft warning lights.[17]

The span is supported by two main cables, which suspend the deck and are held up by the suspension towers. Each cable is 20 inches (51 cm) in diameter and contains 10,800 miles (17,400 km) of individual wires.[18] At the Wards Island and Astoria ends of the suspension span, there are two anchorages that hold the main cables.[9] The anchorages contain a combined 133,500 tons of concrete.[18]

Harlem River lift bridge (NY 900G)

New York State Route 900G | |

|---|---|

| Location | Manhattan–Randall's Island |

| Length | 0.66 mi[19] (1,060 m) |

The Harlem River span is a lift bridge that connects Manhattan with Randalls Island, designed by chief engineer Ammann.[14] It carries six lanes of New York State Route 900G (NY 900G), an unsigned reference route, as well as two sidewalks, one on each side. The span connects to the Harlem River Drive and the FDR Drive, as well as the intersection of Second Avenue and East 125th Street, in East Harlem, Manhattan. A direct-access ramp leads from the westbound bridge to the northbound Harlem River Drive.[12] At the time of its completion, the Harlem River lift bridge had the largest deck of any lift bridge in the world, with a surface area of 20,000 square feet (1,900 m2). To lighten the deck, it was made of asphalt paved onto steel girders, rather than of concrete.[20]

The movable span is 310 feet (94 m) long, and the side spans between the movable span and the approach viaducts are each 195 feet (59 m) long. The total length of the bridge is 700 feet (213 m).[20] The towers are 210 feet (64 m) above mean high water. Each of the lift towers is supported by two clusters of four columns, which supports the bridge deck. A curved truss at the top of each pair of column clusters forms an arch directly underneath the deck.[20]

The lift span is 55 feet (17 m) above mean high water in the "closed" position, but can be raised to 135 feet (41 m). The movable section is suspended by a total of 96 wire ropes, which are wrapped around pulleys with 15-foot (4.6 m) diameters.[21] These pulleys, in turn, are powered by four motors that can operate at 200 horsepower (149 kW).[20][22]

Major intersections

NY 900G is officially maintained as a north-south route, despite its largely east-west progression.[19] The entire route is in the New York City borough of Manhattan. All exits are unnumbered.

| Location | mi[23] | km | Destinations | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randall's Island | 0.0 | 0.0 | Exit 46 on I-278 | ||

| Randall's Island, Icahn Stadium | |||||

| 0.1 | 0.16 | Toll gantry (southbound only) | |||

| Harlem River | 0.2– 0.4 | 0.32– 0.64 | Bridge | ||

| East Harlem | 0.4 | 0.64 | Exit 17 on FDR/Harlem River Drive | ||

| 0.6 | 0.97 | 124th Street | Southbound entrance only | ||

| 2nd Avenue / 125th Street / 126th Street | At-grade intersection; northern terminus | ||||

1.000 mi = 1.609 km; 1.000 km = 0.621 mi

| |||||

Bronx Kill crossing (I-278)

The Bronx Kill span is a truss bridge that connects the Bronx with Randalls Island. It carries eight lanes of I-278, as well as two sidewalks, one on each side. The span connects to Major Deegan Expressway (I-87) and the Bruckner Expressway (I-278) in Mott Haven, Bronx.[12] It originally connected to the intersection of East 134th Street and Cypress Avenue, a site now occupied by the interchange between I-87 and I-278.[13] The truss span was designed by consulting engineers Ash-Howard-Needles and Tammen.[14]

The Bronx Kill span contains three main truss crossings, which are fixed spans because the Bronx Kill is not used by regular boat traffic.[22] The main truss span across the Bronx Kill is 383 feet (117 m) long,[14] while the approaches are a combined 1,217 feet (371 m).[3][14] The total length of the bridge is 1,600 feet (488 m). The truss span is 55 feet (17 m) above mean high water.[14]

Interchange plaza and approach viaducts

The three spans of the RFK Bridge intersect at a grade-separated T-interchange on Randalls Island.[12] The span to Manhattan intersects perpendicularly with the I-278 viaduct between the Bronx and Queens spans.[22] Although I-278 is signed as a west-east highway, the orientation of I-278 on the bridge is closer to a north-south alignment, with the southbound roadway carrying westbound traffic, and the northbound roadway carrying eastbound traffic.[12] Two circular ramps carry traffic to and from eastbound I-278 and the RFK lift bridge to Manhattan.[12][24][25] Randalls and Wards Islands are accessed via exits and entrances to and from westbound I-278; to and from the westbound lift bridge viaduct; to eastbound I-278; and from the eastbound lift bridge viaduct. Eastbound traffic on I-278 accesses the island by first exiting onto the lift bridge viaduct.[12]

The interchange plaza originally contained two tollbooths: one for traffic traveling to and from Manhattan, and one for traffic traveling on I-278 between the Bronx and Queens. The tollbooths were arranged so vehicles only paid one toll upon entering Randalls and Wards Islands, and there was no charge to exit the island.[4][24][25] The elevated toll plazas had a surface area of about 9 acres (3.6 ha) and were supported by 1,700 columns, all hidden behind a concrete retaining wall.[24] In 2017, the MTA started collecting all tolls electronically at the approaches to each bridge,[26] and the tollbooths were removed from the toll plazas on the RFK Bridge and all other MTA Bridges and Tunnels crossings.[27][28]

The Robert Moses Administration Building, a two-story Art Deco structure designed by Embury, served as the headquarters of the TBTA (now the MTA's Bridges and Tunnels division). The building was next to the Manhattan span's plaza, to which it was connected. In 1969, the Manhattan span's toll plaza was relocated west and the I-278 toll plaza was relocated south, and both toll plazas were expanded more than threefold. This required the destruction of the building's original towers. A room was built in 1966 to store Moses's models and blueprints of planned roads and crossings, but they were relocated to the MTA's headquarters at 2 Broadway in the 1980s. The building was renamed after Moses in 1989.[29]

The interchange plaza connects with the over-water spans via a three-legged concrete viaduct that has a total length of more than 2.5 miles (4.0 km). The segments of the viaduct rest atop steel girders, which in turn are placed perpendicularly between concrete piers spaced 60 to 140 feet (18 to 43 m) apart.[20] Each pier is supported by a set of three octagonal columns. The viaduct is mostly eight lanes wide, except at the former locations of the toll plazas, where it widens. The viaduct once traversed Little Hell Gate, a small creek that formerly separated Randalls Island to the north and Wards Island to the south; the waterway has since been filled in.[24] The viaduct rose 62 feet (19 m) above the mean high water of Little Hell Gate.[22]

History

Initial plans

Edward A. Byrne, chief engineer of the New York City Department of Plant and Structures, first announced plans for connecting Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx in 1916.[30][14] The next year, the Harlem Boards of Trade and Commerce and the Harlem Luncheon Association announced their support for such a bridge, which was proposed to cost $10 million. The "Tri-Borough Bridge", as it was called, would connect 125th Street in Manhattan, St. Ann's Avenue in the Bronx, and an as-yet-undetermined location in Queens. It would parallel the Hell Gate Bridge, a railroad bridge connecting Queens and the Bronx via Randalls and Wards Islands.[31] Plans for the Tri-Borough Bridge were bolstered by the 1919 closure of a ferry between Yorkville in Manhattan and Astoria in Queens.[32]

A bill to construct the bridge was proposed in the New York State Legislature in 1920.[33] Gustav Lindenthal, who had designed the Hell Gate Bridge, criticized the Tri-Borough plan as "uncalled for", as the new Tri-Borough Bridge would parallel the existing Hell Gate Bridge. He stated that the Hell Gate Bridge could be retrofitted with an upper deck for vehicular and pedestrian use.[34] Queens borough president Maurice K. Connolly also opposed the bridge, arguing that there was no need to construct a span between Queens and the Bronx due to low demand. Connolly also said that a bridge between Queens and Manhattan needed to be built further downstream, closer to the Queensboro Bridge, which at the time was the only bridge between the two boroughs.[35][36]

The Port of New York Authority included the proposed Tri-Borough Bridge in a report to the New York state legislature in 1921.[37] The following year, the planned bridge was also included in a "transit plan" published by Mayor John Francis Hylan, who called for the construction of the Tri-Borough Bridge as part of the city-operated Independent Subway System (see § Public transportation).[38][39] In March 1923, a vote was held on whether to allocate money to perform surveys and test borings, as well as create structural plans for the Tri-Borough Bridge. The borough presidents of Manhattan and the Bronx voted for the allocation of the funds, while the presidents of Queens and Staten Island agreed with Hylan, who preferred the construction of the new subway system instead of the Tri-Borough Bridge.[40] The bridge allocation was ultimately not approved.[41] Another attempt at obtaining funds was declined in 1924, although there was a possibility that the bridge could be built based on assessment plans that were being procured.[42]

Funding

The Tri-Borough Bridge project finally received funding in June 1925, when the city appropriated $50,000 for surveys, test borings and structural plans. Work started on a tentative design for the bridge.[3][43] By December 1926, the $50,000 allotment had been spent on bores.[44] Around the same time, the proposal to convert the Hell Gate Bridge resurfaced.[45] Albert Goldman, the Commissioner of Plant and Structures, had finished a tentative report for the Tri-Borough Bridge by that time; however, it was not immediately submitted to the New York City Board of Estimate as a result of a reorganization of the city's proposed budget.[46][47] Goldman finally published the report in March 1927, stating that the bridge was estimated to cost $24.6 million.[48] He explained that the Hell Gate Bridge only had enough space for five lanes of roadway, so a new bridge would have to be constructed parallel to it.[49]

Though two mayoral committees endorsed the Tri-Borough plan,[50] as did several merchants' associations,[51] construction was delayed for a year because of a lack of funds.[52] However, the Board of Estimate did approve $150,000 for preliminary borings and soundings.[53] Following this, in September 1927, a group of entrepreneurs proposed to fund the bridge privately.[54] Under this plan, the bridge would be set up as a toll bridge, and ownership would be transferred to the city once the bridge was paid for.[55] In August 1928, Mayor Jimmy Walker received a similar proposal from the Long Island Board of Commerce to build the Tri-Borough Bridge using $32 million of private capital.[56] The Queens Chamber of Commerce also favored setting up tolls on the bridge to pay for its construction.[57] Yet another plan called for financing the bridge using proceeds from a bond issue, which would also pay for the proposed Queens–Midtown Tunnel.[58]

The Tri-Borough Bridge was being planned in conjunction with the Brooklyn–Queens Expressway, which would create a continuous highway between the Bronx and Brooklyn with a southward extension over The Narrows to Staten Island. In January 1929, New York City aldermanic president Joseph V. McKee endorsed the bridge, saying there was enough funding to begin one of four proposed bridges on the expressway's route.[59] The newly elected borough president of Queens, George U. Harvey, also endorsed the bridge, as did Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce leader George Vincent McLaughlin.[60] Trade groups petitioned Mayor Walker to take up the bridge's construction.[61] By the end of the month, Walker acquiesced, and he had included both the Tri-Borough Bridge and a tunnel under the Narrows in his 10-year traffic program.[62] The preliminary borings were completed by late February 1929.[63] The results of the preliminary borings showed that the bedrock in the ground underneath the proposed bridge was sufficient to support the spans' foundations.[64]

In early March, the Board of Estimate voted to start construction on the bridge and on the Narrows tunnel once funding was obtained. The same month, the board allocated $3 million toward the bridge's construction.[65][66] Separately, the Board of Estimate voted to create an authority to impose toll charges on both crossings.[67] In April 1929, the New York state legislature voted to approve the Tri-Borough Bridge as well as a prison on Rikers Island before adjourning for the fiscal year.[68] The same month, New York state governor Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the bill to approve the relocation of about 700 beds in Wards Island's mental hospital, which were in the way of the proposed bridge's suspension span to Queens.[69] The New York state legislature later approved a bill that provided for the relocation of the Queens span's Wards Island end, 1,100 feet (340 m) to the west, thereby preserving hospital buildings from demolition.[70]

The bridge was ultimately planned to cost $24 million and was planned to start construction in August 1929.[71] By July, the groundbreaking was scheduled for September.[72] The preliminary Triborough Bridge proposal comprised four bridges: a suspension span across the East River to Queens; a truss span across Bronx Kill to the Bronx; a fixed span across the Harlem River to Manhattan; and a steel arch viaduct across the no-longer-extant Little Hell Gate between Randalls and Wards Islands.[72]

In August 1929, plans for the bridge were submitted to the United States Department of War for approval to ensure that the proposed Tri-Borough Bridge would not block any maritime navigation routes. Railroad and shipping groups objected that the proposed Harlem River span, with a height of 50 feet (15 m) above mean high water, was too short for most ships, and suggested building a 135-foot-high (41 m) suspension span over the Harlem River instead.[73] Because of complaints about maritime navigational clearance, the Department of War approved an increase in the Harlem River fixed bridge's height to 55 feet (17 m), as well as an increase in the length of the Hell Gate suspension bridge's main span from 1,100 to 1,380 feet (340 to 420 m).[70]

Construction

The scale of the Triborough Bridge project, including its approaches, was such that hundreds of large apartment buildings were demolished to make way for it. The structure used concrete from factories "from Maine to the Mississippi", and steel from 50 mills in Pennsylvania. To make the formwork for pouring the concrete, a forest's worth of trees on the Pacific Coast was cut down.[8] Robert Caro, the author of a biography on Long Island State Parks commissioner and Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority chairman Robert Moses, wrote about the project:

Triborough was not a bridge so much as a traffic machine, the largest ever built. The amount of human energy expended in its construction gives some idea of its immensity: more than five thousand men would be working at the site, and these men would only be putting into place the materials furnished by the labor of many times five thousand men; before the Triborough Bridge was completed, its construction would have generated more than 31,000,000 man-hours of work in 134 cities in twenty states.[4]

Initial efforts

The Board of Estimate approved the first contracts for the Triborough Bridge in early October 1929, specifically for the construction bridge piers on Randalls and Wards Islands and in Queens. This allowed for the start of construction on the Triborough Bridge's suspension span to Queens.[70] A groundbreaking ceremony was held in Astoria Park, Queens, on October 25, 1929, just a day after Black Thursday, which started the Great Depression.[18] Mayor Walker turned over the first spadeful of dirt for the bridge in front of 10,000 visitors.[74] After the groundbreaking ceremony, further construction was delayed because the company originally contracted to build the piers, the Albert A. Volk Company, refused to carry out the contract. In early December, the contract for the piers was reassigned to the McMullen Company.[75] Meanwhile, the Board was condemning the land in the path of the bridge's approaches.[76] However, this process was also postponed because homeowners wanted to sell their property to the city at exceedingly high prices.[77]

The War Department gave its approval to the Bronx Kills, East River, and Little Hell Gate spans in late April 1930, after construction was already underway on the Queens suspension span across the East River.[78] A week later, the War Department also approved the Harlem River span, with another amendment: the span was now a movable lift bridge, which could be raised to allow maritime traffic to pass.[79] Shortly afterward, a special mayoral committee sanctioned a $5 million expenditure for the Triborough project,[80] and in July 1930, a $5 million bond issue to fund the Triborough Bridge's construction was passed.[81]

Plans for an expressway to connect to the bridge's Queens end were also filed in July 1930. This later became the Brooklyn Queens Expressway, which was connected to the bridge via the Grand Central Parkway.[82] There were also proposals for an expressway to connect to the Bronx end of the bridge along Southern Boulevard.[83] Robert Moses, the Long Island state parks commissioner, wanted to expand Grand Central Parkway from its western terminus at the time, Union Turnpike in Kew Gardens, Queens, northwest to the proposed bridge.[84] The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway proposal, which would create a highway from the Queens end of the bridge to Queens Boulevard in Woodside, Queens, was also considered.[85]

A contract to build the suspension anchorage on Wards Island was awarded in January 1931.[86] At the time, progress on the bridge approaches was proceeding rapidly, and it was expected that the entire Triborugh Bridge complex would be completed in 1934.[13] By August 1931, it was reported that the Wards Island anchorage was 33% completed, and that the corresponding anchorage on the Queens side was 15% completed. Work on drainage dikes, as well as contracts for bridge approach piers, were also progressing.[87] A report the next month indicated that the overall project was 6% completed, and that another $2.45 million in contracts was planned to be awarded over the following year.[88][89] In October, contracts for constructing the bridge piers were advertised.[90] By December 1931, the project was 15% completed,[91] and the city was accepting designs for the Queens span's suspension towers.[92] The granite foundations in the water near each bank of the East River, which would support the suspension towers, were completed in early or mid-1932.[93][94] At the time, there were no funds to build six additional piers on Randalls Island and one in Little Hell Gate, nor were there funds to build the suspension towers themselves.[93]

Funding issues

The Great Depression severely impacted the city's ability to finance the Triborough Bridge's construction.[18] City comptroller Charles W. Berry had stated in February 1930 that the city was in sound financial condition, even though other large cities were nearing bankruptcy.[95] However, the New York City government was running out of money by that July.[96] The Triborough project's outlook soon began to look bleak. Chief engineer Othmar Ammann was enlisted to help guide the project, but the combination of Tammany Hall graft, the stock market crash, and the Great Depression which followed it, brought the project to a virtual halt.[97] Investors shied away from purchasing the municipal bonds needed to fund it.[5]

By the spring of 1932, the Triborough Bridge project was moribund.[98] As part of $213 million in cuts to the city's budget, Berry wanted to halt construction on the span in order to avoid a $43.7 million budget shortage by the end of that year.[99] With no new contracts being awarded, the chief engineer of the Department of Plant and Structures, Edward A. Byrne, warned in March 1932 that construction on the Triborough Bridge would have to be halted.[100] Though Queens borough president Harvey objected to the impending postponement of the bridge's construction,[101] the project was still included in the $213 million worth of budget cuts.[102] Following this, Goldman submitted a proposal to fund the planning stages for the remaining portions of construction, so that work could resume immediately once sufficient funding was available.[103]

In August 1932, Senator Robert F. Wagner announced that he would ask for a $26 million loan from the federal government, namely President Herbert Hoover's Reconstruction Finance Corporation, so there could be funds for the construction of both the Triborough Bridge and Queens-Midtown Tunnel.[104] Queens borough president Harvey also went to the RFC to ask for funding for the bridge.[105] Soon after, the RFC moved to prepare the loan for the Triborough Bridge project.[106] However, when Mayor Walker resigned suddenly in September 1932, his successor Joseph V. McKee refused to seek RFC or other federal aid for the two projects, stating, "If we go to Washington for funds to complete the Triborough Bridge [...] where would we draw the line?"[107] Governor Al Smith agreed, saying that such requests were unnecessary because the bridge could pay for itself.[108] Harvey continued to push for federal funding for the Triborough Bridge, prioritizing its completion over other projects such as the development of Jamaica Bay in southern Queens.[109] Civic groups also advocated for the city to apply for RFC funding.[110]

In February 1933, a nine-person committee, appointed by Lehman and chaired by Moses, applied to the RFC for a $150 million loan for projects in New York state, including the Triborough Bridge.[111] However, although the RFC favored a loan for the Triborough project,[112] the new mayor, John P. O'Brien, banned the RFC from giving loans to the city.[113] Instead, O'Brien wanted to create a bridge authority to sell bonds to pay for the construction of the Triborough Bridge as well as for the Queens-Midtown Tunnel.[114] Robert Moses was also pushing the state legislature to create an authority to fund, build, and operate the Triborough Bridge.[97] A bill to create the Triborough Bridge Authority (TBA) passed quickly through both houses of the state legislature,[115] and was signed by Governor Herbert H. Lehman that April. The bill included a provision that the authority could sell up to $35 million in bonds and fund the remainder of construction through bridge tolls.[116][117] George Gordon Battle, a Tammany Hall attorney, was appointed as chairman of the new authority, and three commissioners were appointed.[118]

Shortly after the TBA bill was signed, the War Department extended its deadline for the Triborough Bridge's completion by three years, to April 28, 1936.[119] Lehman also signed bills to clear land for a bridge approach in the Bronx,[120] and he promised to resume construction of the bridge.[121] That May, the TBA asked the RFC for a $35 million loan to pay for the bridge.[122][123] The RFC ultimately agreed in August to grant $44.2 million, to be composed of a loan of $37 million, as well as a $7.2 million subsidy.[124] However, the loan would only be given under a condition that 18,000 workers be hired first,[125] so the city's Board of Estimate voted to hire 18,000 workers to work on the Triborough project.[126] The funds for the Triborough Bridge, as well as for the Lincoln Tunnel from Manhattan to New Jersey, were ready by the beginning of September.[127]

Construction resumes

The city purchased land in the path of the Triborough Bridge in September 1933,[128] and construction on the Triborough Bridge resumed that November.[98] By January 1934, contracts were being prepared for the completion of the suspension span and the construction of the other three spans;[129] one of these contracts included the construction of the bridge's piers.[130] Families living in the path of the bridge's approaches protested against the eviction notices given to them.[131] The construction of the Triborough Bridge across Little Hell Gate also required the demolition of hospital buildings on Randalls and Wards Islands.[132] Work on land-clearing for the bridge began that April.[133] The New York City Department of Hospitals later decided to apply for funds to build the Seaview Hospital on Staten Island, which would house the hospital facilities displaced by the Triborough Bridge.[134]

In February 1934, the TBA contemplated condensing the Queens span's 16-lane, double-deck roadway into an 8-lane, single deck road, as well as simplify the suspension towers' designs, in order to save $5 million.[135] With a 16-lane capacity, the span would have been able to carry 40 million vehicles a year, but this was not projected to be reached until forty years after the bridge's opening.[136] In April, a new plan was approved that would reduce the bridge's cost from $51 million to $42 million so the subsidy could pay for the bridge's entire cost.[136][137][138] Chief engineer Ammann had decided to collapse the original design's two-deck roadway into one, requiring lighter towers and lighter piers.[97] The steel company constructing the towers challenged the TBA's decision in an appellate court, but the court ruled in favor of the TBA.[139]

During this time, the TBA was in turmoil: by January 1934, one of the TBA's commissioners had resigned,[140] and New York City Mayor Fiorello H. La Guardia was trying another TBA commissioner, John Stratton O'Leary, for corruption.[141] As a result, Public Works Administration (PWA) administrator Harold L. Ickes refused to distribute more of the RFC grant until the existing funds could be accounted for.[142] After O'Leary had been removed, La Guardia appointed Moses to the position.[143] After O'Leary's removal, Ickes gave the city $1.5 million toward the bridge's construction.[144][145] Moses became the chairman of the TBA in April 1934, after a series of interim chairmen had held the post.[146] Moses leveraged his leadership of the Authority as well as the state and city positions he also held, to expedite the project.[98] The first major construction contract after Moses gained control of the TBA was awarded in May 1934, for the construction of an approach highway to the Queens span.[147]

Moses continued to advocate for new roads and parkways to feed into the bridge. The complex of roads included the Grand Central Parkway and Astoria Boulevard in Queens; 125th Street, the East River Drive (now the FDR Drive), and Harlem River Drive in Manhattan; and Whitlock Avenue and Eastern Boulevard (now Bruckner Expressway) in the Bronx.[148] All of these roads would be part of an interconnected parkway system that would allow cars to move smoothly through the New York City area.[149] Civic groups also wanted a road from the West Bronx to connect to the bridge, but it was rejected.[150] The first of those roads, the Grand Central Parkway extension from Kew Gardens to the Triborough Bridge, was planned to start construction in spring 1934.[151] Further changes to the plan for the Bronx span came in July 1934: instead of being a lift bridge, as originally proposed, it was approved by the Department of War as a fixed truss span, since the Bronx Kill was not a navigable waterway. However, it could be replaced with a lift bridge if needed.[148][152] The same month, the city approved construction for the first segment of the East River Drive, leading from York Avenue and 92nd Street to the Triborough Bridge approach at 125th Street.[153][154] The bridge approach on the Bronx side was finalized, running along Southern and Eastern Boulevards,[154] with a future extension to Pelham Bay Park in the northeastern Bronx.[155] The Board of Estimate approved the East River Drive approach that October, while voting against the proposed West Bronx approach highway.[156]

While reformers embraced Moses's plans to expand the parkway system, state and city officials were overwhelmed by their scale, and slow to move to provide financing for the vast system.[97] Partial funding came from interest-bearing bonds issued by the Triborough Bridge Authority, to be secured by future toll revenue.[157][158] Financing disputes with the PWA involved complex political infighting between Moses, Ickes, now-President Roosevelt, and Mayor La Guardia.[159] The political disputes peaked in January 1935, when Ickes passed a rule that effectively prohibited PWA funding for the TBA unless Moses resigned the post of either TBA chairman or New York City Parks Commissioner.[160] This came as a result of Moses's criticism that New Deal funding programs like the PWA were too slow to disburse funds.[161] Ickes threatened to withhold salaries for TBA workers as well.[162] Though La Guardia was supportive of Moses, even petitioning Roosevelt to intervene, he was willing to replace the TBA chairman if it resulted in funding for the bridge, since Roosevelt sided with Ickes.[163] In mid-March, Ickes suddenly backed down on his ultimatum, and not only was Moses allowed to keep both of his positions, but also the PWA resumed its payments to the TBA.[164][165][166]

Significant progress

In February 1935, while the feud between Moses and Ickes was ongoing, the TBA awarded a contract to build supporting piers for the Harlem River lift structure to Manhattan.[167] Despite an impending lack of funds due to the dispute between Moses and Ickes, the TBA announced its intent to open bids for bridge steelwork.[168] By March, the suspension towers for the East River span to Queens were nearing completion, as only the tops of the towers remained outstanding. The support piers on Randalls and Wards Islands had progressed substantially.[155] After the Moses/Ickes dispute had subsided, the TBA started advertising for bids to build the steel roadways of the Randalls and Wards Islands viaducts, as well as the East River suspension span.[169] Less than a week afterward, the first temporary wires were strung between the two towers of the suspension span, marking the future locations of that span's main cables.[170] A contract for the Harlem River lift span's steel superstructure was awarded that May,[171] followed by a contract for the Bronx Kill truss span's structure the following month.[172]

The spinning of the main span's suspension cables was finished in July 1935. By that time, half of the $41 million federal grant had been spent on construction, and the bridge was expected to open the following year.[173] The projected completion of the Triborough Bridge in July 1936 was expected to relieve traffic on highways in the New York City area,[174] and with the upcoming 1939 New York World's Fair being held in Queens, it would also provide a new fast route to the fairground at Flushing Meadows–Corona Park.[175] By October 1935, the Queens approach and the Randalls and Wards Islands viaduct was nearly complete. Vertical suspender cables had been hung from the main cables of the Queens suspension span, and the steel slabs to support the span's roadway deck were being erected. However, progress on the Bronx and Manhattan spans had not progressed as much: the concrete piers supporting Bronx span were being constructed, and the site of the Manhattan span was marked only by its foundations.[176] The deck of the Queens suspension span was completed the following month.[177]

%252C_Queens_County%252C_NY_HAER_NY%252C41-QUE%252C2-21_(cropped).tif.jpg.webp)

In November 1935, a controversy emerged over the fact that the Triborough Bridge would use steel imported from Nazi Germany, rather than American producers.[178] Although American steel producers objected to the contract, the PWA approved of it anyway, because the German steel contract was cheaper than any of the bids presented by American producers.[179] Moses also approved of the decision because it would save money.[180][181] However, La Guardia blocked the deal, writing that "the only commodity we can get from Hitlerland [Germany] is hatred, and we don't want any in our country."[182] Shortly afterward, imported materials were banned for use on any PWA projects.[183]

By February 1936, the TBA had awarded contracts for paving the Bronx Kill and East River spans, as well as for constructing several administrative buildings for the TBA near the bridge.[184] Moses wanted to speed up construction on the Triborough Bridge so that it would meet a deadline of July 11, 1936. He objected to an order that Ickes made in March 1936, decentralizing control of PWA resident engineers, who would report to state PWA bosses instead of directly to the PWA's main office in Washington, D.C. Moses believed that the PWA boss for New York, Arthur S. Tuttle, was indecisive.[185] In return, Ickes assured Moses of Tuttle's full cooperation.[186] Moses also appealed to Ickes to increase the construction workers' workweeks from 30 to 40 hours so the bridge would be able to open on time, but was initially rejected.[187][188] A 40-hour workweek was approved in June 1936, one month before the bridge's projected opening.[189]

The 300-by-84-foot superstructure of the Harlem River lift span was assembled in Weehawken, New Jersey. It was floated northward to the Triborough Bridge site in April 1936.[190] Early the next month, the 200-ton main lift span was hoisted into place above the Harlem River in a process that took sixteen minutes.[191] In addition, the city gave the New York City Omnibus Corporation a temporary permit to operate bus routes on the Triborough Bridge, connecting the bus stops on each of the bridge's ends, during the summer months.[192]

A byproduct of the Triborough project was the creation of parks and playgrounds in the lands underneath the bridges and approaches.[98] The largest of these parks was Randall's Island Park, located on Wards and Randalls Islands.[193][194] The park on Randalls Island was approved in February 1935,[195] and included the construction of an Olympic-sized running track called Downing Stadium, work on which began in summer 1935.[194][196][197] Smaller parks were also built in Astoria and Manhattan.[98][3]

Opening

By May 1936, the opening ceremonies for both the Triborough Bridge and the Downing Stadium were scheduled for July 11.[198] The dedication was scheduled to occur on the Manhattan lift span.[199] Due to the previous conflicts between President Roosevelt and Robert Moses, the attendance of the former was not certain until two weeks before the ceremony.[200] PWA administrator Ickes's attendance was only finalized four days beforehand.[201]

The completed structure, described by The New York Times as a "Y-shaped sky highway", was dedicated on July 11, 1936, along with the Downing Stadium.[202] The ceremony for the Triborough Bridge was held at the interchange plaza, and was attended by President Roosevelt, Mayor La Guardia, Governor Lehman, PWA administrator Ickes, and Postmaster General James A. Farley, who all gave speeches.[203][204] Robert Moses acted as the master of ceremonies.[202][205] The ceremonies were broadcast via a nationwide radio connection.[205] A parade was also held on 125th Street in Manhattan to celebrate the bridge's opening.[206] The Triborough Bridge opened to the general public at 1:30 p.m., and by that midnight an estimated 200,000 people had visited the bridge via car, bus, or foot.[202][10] The next day, 40,000 vehicles used the bridge on its first full day of service.[207] July 13 was the first weekday that the bridge was in service, and it saw about 1,000 vehicles an hour.[208] In the first month of service, the TBA recorded an average bridge usage of 31,000 vehicles per day.[209] The American Institute of Steel Construction later declared the Triborough Bridge to be the most beautiful steel bridge constructed in 1936.[210]

The ferry between Yorkville, Manhattan, and Astoria, Queens, was made redundant by the new Triborough Bridge. Upon the bridge's opening, Moses unsuccessfully attempted to destroy the ferry house before being stopped by La Guardia.[211][212] The city had closed the ferry by the end of July.[213] Traffic on the Queensboro Bridge, the only other vehicular bridge that connected Manhattan and Queens, declined after the Triborough Bridge opened.[214]

The Triborough Bridge, the largest PWA project in the eastern U.S.,[215] cost $60 million (equivalent to $1 billion in 2021) according to final TBA figures.[98] Based on expenditures, the PWA had originally estimated the bridge's cost to be as high as $64 million.[215][216] In either case, the Triborough Bridge was one of the largest public works projects of the Great Depression, more expensive than the Hoover Dam.[3][205][217] Of this, $16 million came from the city and $9 million directly from the PWA. The latter also purchased $35 million worth of TBA bonds, which were eventually bought back and resold to the public.[98] The PWA had finished giving out the $35 million loan by February 1937,[218] and the Reconstruction Finance Corporation had sold the last of the TBA's funds that July.[219] Additional funding came from toll collection: the toll was initially set at 25 cents per passenger car, with lower rates for motorcycles and higher rates for commercial vehicles.[220] In the first year of the bridge's operation it generated $2.72 million (equivalent to $51.27 million in 2021), collected from 9.65 million vehicles.[5]

Early years

When the bridge opened, none of the spans had direct connections to the greater system of highways in New York City.[7] In Queens, the Grand Central Parkway extension to the Triborough Bridge was nearly completed at the time of the bridge's opening. The Manhattan span was planned to connect to the East River Drive (now the FDR Drive), the first segments of which were still under construction.[7] The section of the East River Drive from the bridge south to 92nd Street opened that October.[221]

The Bronx span ended in local traffic at the no-longer extant intersection of 135th Street and Cypress Avenue.[7] The first of two approach highways in the Bronx was approved late in 1936;[222] it connected to the West Bronx, following the present route of the Major Deegan Expressway (I-87) northwest to the intersection of 138th Street and Grand Concourse, where there were flyover ramps connecting to the Grand Concourse.[223] Another approach highway in the Bronx, the present Bruckner Boulevard, was approved in 1938.[224] This highway was built on the site of Whitlock Avenue, extending northeast through the South Bronx from the bridge to the Bronx River, where it followed Eastern Boulevard eastward to what is now the Bruckner Interchange.[225] Both Bronx approach roads were completed quickly in preparation for the 1939 New York World's Fair, which was held in Queens. The first segment of the West Bronx approach highway to the Grand Concourse was opened in April 1939, in time for the fair.[226] The West Bronx highway later became part of the Major Deegan Expressway, an Interstate-standard highway that reached to the New York State Thruway at the New York City border.[227]

Originally, there was no direct access from the Queens span to Wards Island, but in November 1937, Moses announced the construction of a ramp from the Queens span that would lead down to the island.[228] The next year, a lawsuit was filed by two Wards Islands landowners, who alleged that the Triborough Bridge had been built on portions of their land. They each received nominal damages of $1.[229][230]

The Triborough Bridge Authority was headquartered in an administration building adjacent to the Manhattan span's toll plaza, where by 1940, it controlled the operation of all toll bridges located entirely within New York City.[29] An additional bridge between the Bronx and Queens, the Bronx–Whitestone Bridge, was opened in April 1939.[231][232] However, the Triborough Bridge did not see any initial decline in traffic, likely because both spans were heavily used during the World's Fair.[233] Soon after, vehicle rationing caused by the onset of World War II resulted in a decline in traffic at crossings operated by the TBA including the Triborough Bridge.[234] Still, by 1940, the Triborough Bridge was the most profitable crossing operated by the TBA.[235] The TBA became the Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority (TBTA) in 1946 after it took over the construction of the Queens–Midtown Tunnel and Brooklyn–Battery Tunnel, though TBTA operations continued to be managed from the Triborough Bridge.[236]

Years after the Triborough Bridge's opening, Moses continued expanding the system of highways in the New York City area, including arteries that led to the Triborough Bridge. Construction on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway in Queens—between the Grand Central Parkway interchange, just east of the Triborough Bridge, and the Kosciuszko Bridge at the Brooklyn border—was underway by the late 1940s.[237] In addition, Moses wanted to build an elevated expressway atop Bruckner Boulevard.[238] In 1956, the New York City Planning Commission approved the upgrade of Bruckner Boulevard between the Triborough Bridge and the Bruckner Interchange to a grade-separated expressway as part of the Interstate Highway System.[239] The entire Bruckner Expressway except for the Bruckner Interchange opened in 1962,[240] while the entire Brooklyn-Queens Expressway was completed in 1964.[241] Both segments became part of I-278, as did the Queens and Bronx spans of the Triborough Bridge.[242]

Later history

.jpg.webp)

In 1968, the Triborough Bridge received its first major renovation in its 31-year history. Seven tollbooths were added, three at the Manhattan span's toll plaza and four at the Queens/Bronx spans' toll plaza, and several ramps were widened at a cost of $20 million. The project also added a direct ramp from the Manhattan span to the southbound lanes of Second Avenue in East Harlem.[243] The TBTA administration building was also expanded during this project.[29] Traffic from the Manhattan span was temporarily diverted during this project.[244][245]

In 1997, more renovations were announced as part of the Triborough Bridge Rehabilitation Project.[246] The project consisted of three phases. The first phase involved renovating the Queens span and approach ramps, as well as replacing the suspender cables. On the Queens side, an exit ramp from westbound I-278 to 31st Street necessitated the destruction of the entrance to the southern sidewalk. The second phase involved renovating the Bronx span and approach ramps. The third phase involved renovating the Manhattan span and approach ramps.[247] Work on replacing the Queens span's suspender cables and adding an orthotropic deck to the Queens suspension span started in 2000.[248][249]

At some point in the past, a sign on the bridge informed travelers, "In event of attack, drive off bridge," New York Times columnist William Safire wrote in 2008. The "somewhat macabre sign", he wrote, must have "drawn a wry smile from millions of motorists."[250]

On November 19, 2008, the Triborough Bridge was officially renamed after Robert F. Kennedy, former U.S. Senator representing New York and U.S. Attorney General, at the request of the Kennedy family.[251] Forty years had passed since Kennedy had been assassinated during a 1968 presidential bid.[252][253][254] Traffic and news reports have come to commonly refer to the bridge as the "RFK Triborough Bridge" and at times simply the "Triborough Bridge" to avoid confusion among residents long accustomed to its original name.[255]

The MTA announced further renovations to the Triborough Bridge in 2008; the work included the replacement of the roadways at the toll plazas, as well as the rehabilitation of various ramps and the construction of a new service building.[246] The same year, the MTA awarded contracts to renovate the Queens span's anchorages.[256] In 2015, the MTA started two reconstruction projects on different parts of the bridge[257] as part of a $1 billion, 15-year program to renovate the bridge complex.[258] The MTA commenced construction on a $213 million rehabilitation of the 1930s-era toll plaza between the Queens and Bronx spans, which included a rebuilding of the roadway and the supporting structure underneath. The new toll plaza structure was completed in 2019.[257]

Cashless tolling was implemented on June 15, 2017,[26][259] allowing drivers to pay tolls electronically via E-ZPass or Toll-by-Mail without having to stop at any tollbooths.[26] Shortly afterward, the tollbooths were demolished.[27][28] In addition, a ramp from the Manhattan span to the northbound Harlem River Drive was being built for $68.3 million, and was to be finished by December 2017;[257] however, this was later delayed pending the reconstruction of the Harlem River Drive viaduct around the area.[260] In February 2020, the northbound Harlem River Drive ramp's completion was tentatively announced for 2021.[261][262] At that point, the ramp was expected to cost $72.6 million.[263] The ramp opened in November 2020.[264]

Usage

The toll revenues from the RFK Bridge pay for a portion of the public transit subsidy for the New York City Transit Authority and the commuter railroads.[265] The bridge had annual average daily traffic of 164,116 in 2014. For that year, the bridge saw annual toll-paying traffic rise by 2.9% to 59.9 million, generating $393.6 million in revenue at an average toll of $6.57.[266]

Pedestrian and bicycle sidewalks

The bridge has sidewalks on all three spans where the TBTA officially requires bicyclists to walk their bicycles across[267] due to safety concerns.[268] However, the signs stating this requirement have been usually ignored by bicyclists,[269]: 16 and the New York City Government has recommended that the TBTA should reassess this kind of bicycling ban.[269]: 57 Stairs on the 2 km (1.2 mi) Queens span impede handicapped access, and only the northern sidewalk on that span is open to traffic; the Queens end of the southern sidewalk was demolished in the early 2000s.[270] The two sidewalks of the Bronx span are connected to one long and winding ramp at the Randalls Island end,[271] though another pedestrian bridge between Randalls Island and the neighborhood of Port Morris, Bronx, opened to the east of the RFK Bridge in November 2015.[272]

Public transportation

The RFK Bridge carries the M35, M60 SBS and X80 bus routes operated by MTA New York City Transit, as well as several express bus routes operated by the MTA Bus Company: BxM6, BxM7, BxM8, BxM9, BxM10 and BxM11. The M35 travels from Manhattan to Randalls and Wards Islands (with the X80 also operating during special events), while the M60 SBS runs between Manhattan and Queens, and the MTA Bus express routes travel between Manhattan and the Bronx.[273]

In the 1920s, John F. Hylan proposed building the Triborough Bridge as part of his planned Independent Subway System. The proposal entailed extending the New York City Subway's BMT Astoria Line along the same route the Triborough now follows. It would have created a crosstown subway line along 125th Street, as well as a new subway line in the Bronx under St. Ann's Avenue.[38][39][274]

Tolls

As of April 11, 2021, drivers pay $10.17 per car or $4.28 per motorcycle for tolls by mail/non-NYCSC E-ZPass. E-ZPass users with transponders issued by the New York E‑ZPass Customer Service Center pay $6.55 per car or $2.85 per motorcycle. Mid-Tier NYCSC E-ZPass users pay $8.36 per car or $3.57 per motorcycle. All E-ZPass users with transponders not issued by the New York E-ZPass CSC will be required to pay Toll-by-mail rates.[275]

When the Triborough Bridge opened, it had a combined 22 tollbooths spread across two toll plazas.[220] Motorists were first able to pay with E‑ZPass in lanes for automatic coin machines at the toll plazas on August 21, 1996.[276]

Open-road cashless tolling began on June 15, 2017.[26] The tollbooths were dismantled, and drivers are no longer able to pay cash at the bridge. Instead, there are cameras mounted onto new overhead gantries manufactured by TransCore[277] near where the booths were formerly located.[278][279] A vehicle without an E-ZPass has a picture taken of its license plate and a bill for the toll is mailed to its owner.[280] For E-ZPass users, sensors detect their transponders wirelessly.[278][279][280]

Historical tolls

| Years | Toll | Toll equivalent in 2021[281] |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1936–1972 | $0.25 | $1.62–4.88 | [282][283] |

| 1972–1975 | $0.50 | $2.52–3.24 | [283][284] |

| 1975–1980 | $0.75 | $2.47–3.78 | [284][285] |

| 1980–1982 | $1.00 | $2.81–3.29 | [285][286] |

| 1982–1984 | $1.25 | $3.26–3.51 | [286][287] |

| 1984–1986 | $1.50 | $3.78–3.71 | [287][288] |

| 1986–1987 | $1.75 | $4.17–4.33 | [288][289] |

| 1987–1989 | $2.00 | $4.37–4.77 | [289][290] |

| 1989–1993 | $2.50 | $4.69–5.47 | [290][291] |

| 1993–1996 | $3.00 | $5.18–5.63 | [291][292] |

| 1996–2003 | $3.50 | $6.05–6.05 | [292][293] |

| 2003–2005 | $4.00 | $5.55–6.91 | [293][294] |

| 2005–2008 | $4.50 | $5.66–6.24 | [294][295] |

| 2008–2010 | $5.00 | $6.21–6.29 | [295][296] |

| 2010–2015 | $6.50 | $7.43–8.08 | [296][297] |

| 2015–2017 | $8.00 | $8.84–9.15 | [298][299] |

| 2017–2019 | $8.50 | $9.01–9.40 | [300][301] |

| 2019–2021 | $9.50 | $9.95–$10.07 | [302][303] |

| April 2021 – present | $10.17 | $10.17 | [304] |

See also

- List of bridges documented by the Historic American Engineering Record in New York

- National Register of Historic Places listings in New York County, New York

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Queens County, New York

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Bronx County, New York

- List of reference routes in New York

References

Notes

- "New York City Bridge Traffic Volumes" (PDF). New York City Department of Transportation. 2016. p. 11. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- "Robert F. Kennedy Bridge". Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). Retrieved November 3, 2015.

The Robert F. Kennedy Bridge (formerly the Triborough Bridge), the authority's flagship facility, opened in 1936. It is actually three bridges, a viaduct, and 14 miles of approach roads connecting Manhattan, Queens, and the Bronx.

- See:

- "Triboro Plaza Highlights : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- "Triborough Bridge Playground B Highlights : NYC Parks". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- Caro 1974, pp. 366–395.

- Shanor, Rebecca Read. "Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Bridge [Triborough Bridge]" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. p. 1110. ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2.

- "Triborough Bridge Project". ASCE Metropolitan Section. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- Duffus, R. L. (July 5, 1936). "Bridge Will Speed Up Traffic; Breaking Down Barriers That Have Impeded the Flow In and Out of New York, It Is Part of a Vast and Growing Road System". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- Caro 1974, p. 386.

- "The Triborough Bridge Is Taking Shape; Work Is Expected To Start This Year On The Great Towers Beside Hell Gate". The New York Times. January 24, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "200,000 Rush to Use New Bridge By Auto, Bus, Cycle and on Foot; Presidential Party First to Drive Over 17 1/2 Miles of Span – Rush at All Approaches When Barriers Are Lifted on Word Flashed by Police Radio – Boy Bicyclist First at Toll Booth". The New York Times. July 12, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 10, 2018.

- "Ickes Names Green Project Engineer; Appointee Will Supervise Triborough Bridge And Hudson Tunnel Construction". The New York Times. March 29, 1935. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- Google (November 1, 2018). "Robert F. Kennedy Bridge" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved November 1, 2018.

- "Triborough Bridge Progress Is Rapid; Structure Will Link Boroughs of Manhattan, Queens and the Bronx". The New York Times. February 1, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- Rastorfer 2000, p. 93.

- Rastorfer 2000, p. 106.

- Rastorfer 2000, pp. 110–111.

- Rastorfer 2000, p. 113.

- Feuer, Alan (June 28, 2009). "Deconstructing the Robert F. Kennedy Bridge". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "2014 Traffic Data Report for New York State" (PDF). New York State Department of Transportation. July 22, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2020.

- Rastorfer 2000, p. 102.

- Rastorfer 2000, p. 97.

- Brock, H. I. (April 28, 1935). "A Triborough Giant Flings Out Its Steel Arms". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- Google (January 23, 2020). "New York State Route 900G" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- Rastorfer 2000, p. 105.

- Brock, H. I. (May 12, 1935). "FAST TRAVEL OVER BRIDGE; Triborough Route Will Provide Steady Run Without Lights". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 8, 2018.

- "Cashless Tolls Arrive on RFK Triboro Bridge". Spectrum News NY1. June 15, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2018.

- Walker, Ameena (September 30, 2017). "NYC's last remaining toll booths are removed from bridges and tunnels". Curbed NY. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- "Open road tolling closes gate on era at NYC-area crossings". Newsday. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- "From the B&T Archive: The Robert Moses Building". Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA). January 18, 2011. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- "Triboro Plaza". New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. Retrieved February 25, 2010.

- "Proposed Triborough Bridge Across The Harlem And East Rivers, Connecting Manhattan, Bronx, And Queens Boroughs". The New York Times. January 14, 1917. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Proposed Triborough Bridge Over Harlem And East Rivers". The New York Times. January 5, 1919. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Harlem-To-Queens Bridge Proposed". The New York Times. February 3, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Tri-Boro Bridge is "Uncalled For", Says Lindenthal" (PDF). Greenpoint Daily Star. February 19, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "Connolly Opposes Proposed Bridge" (PDF). New York Sun. February 15, 1920. p. 1. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "Bridge Plan Opposed. Tri-Borough Structure Declared Unnecessary By Queens President". The New York Times. February 7, 1920. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "New Tri-borough Bridge; Port Authority Will Include Structure in Its Report". The New York Times. December 1, 1921. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Hylan Announces His $600,000,000 Plan For Transit; Proposes to Construct 35 More Subways, Extensions, Tunnels and Bridges". The New York Times. August 28, 1922. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Hylan Offers Transit Plan". Daily News. New York. August 28, 1922. p. 26. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hulbert Likens Hylan To A Crab;". The New York Times. May 5, 1923. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Mayor Hylan Going To Albany Today; Will Plead Before Legislature for Home Rule and Transit Bills". The New York Times. March 11, 1924. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "City Won't Pay for Surveys for Tri-Boro Bridge". Daily Star. March 11, 1924. pp. 1, 2 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- "Celebrate Proposed Tri Borough Bridge". The New York Times. June 25, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Tri-borough Bridge Comes Up Monday; Goldman to Tell of Plan Which Then Goes to Berry for Opinion on Financing". The New York Times. December 17, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "New Auto Bridge?". Daily News. New York. December 17, 1926. p. 33. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Cuts To Fit Budget Held Up For Berry; Estimate Board Awaits Report on Sum to Be Available for $713,000,000 Projects". The New York Times. December 21, 1926. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Tri-Borough Span Plans Modified". Daily News. New York. December 21, 1926. p. 69. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Tri-borough Bridge To Cost $24,625,000; Goldman Completes Plans, and Estimate Board Sets April 21 for Public Hearing". The New York Times. March 25, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Triborough Bridge Objections Refuted". Daily News. New York. April 23, 1927. p. 36. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Committee Backs Tri-Borough Bridge; Goldman Project For Queens, Manhattan And Bronx Goes To Plan And Survey Body". The New York Times. May 7, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Merchants Back Tri-borough Bridge; Association Also Approves the Vehicular Tunnel Under the East River". The New York Times. May 22, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Tri-borough Bridge Held Up For A Year; Lack of City Funds Seen as Bar to $25,000,000 Project and the $50,000,000 East River Tube". The New York Times. May 11, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "First Fund Is Voted For Tri-boro Bridge; Estimate Board Appropriates $150,000 for Preliminary Soundings and Borings". The New York Times. May 27, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Offers To Finance Tri-borough Bridge; Capitalists' Committee Tells Acting Mayor Private Funds Can Be Obtained". The New York Times. September 22, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Offers Plan To Pay For Tri-Boro Bridge; B. F. Yoakum Suggests Private Capital Be Used For The Construction". The New York Times. September 29, 1927. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Mayor Gets Bridge Offer; But Declines to Discuss $32,000,000 Tri-Borough Proposal". The New York Times. August 21, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Favors Tolls For Tri-boro Bridge; Feasibility of That Plan Explained by Queens Chamberof Commerce". The New York Times. December 2, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Bond Issue Weighed To Relieve Traffic; Mayor Discusses Program to Ease Congestion at Once With Lawmakers". The New York Times. December 21, 1928. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Says City Has Cash To Start New Span; McKee Urges Agreement on One Bridge to Brooklyn So It Can Be Begun at Once". The New York Times. January 3, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Queens Chief in Tri-Boro Big Three". Daily News. New York. January 4, 1929. p. 368. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Trade Bodies Urge Tri-borough Bridge; Early Action to Ease Traffic Congestion Is Demanded at Bronx Chamber Luncheon". The New York Times. January 18, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "50-year Traffic Aid Pledged By Mayor; He Decries Piecemeal Program and Promises Basis for Full Plan in 3 Months". The New York Times. January 30, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Ready To Construct Tri-borough Bridge; Commissioner Goldman Says Borings for Which Funds Were Provided Are Finished". The New York Times. February 24, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Bridge Borings Finished; Preliminary Tests for Triboro Span Show Bedrock Is Good". The New York Times. August 7, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "City's Boosting Slate Boosted by $156,552,450". Daily News. New York. March 13, 1929. p. 12. Retrieved November 1, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "City Acts To Speed Bridge And Tunnel; Walker and Civic Delegates Go to Albany Today to Urge New Commission". The New York Times. March 13, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Toll Power Voted For Bridge And Tube; Estimate Board Passes Bill to Fix Charges on Triborough Span and Narrows Tunnel". The New York Times. March 22, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- "City Hails Passage Of Bridge Measure; Success of Bills at Albany Opens Way for Tri-Borough Span and Riker's Island Prison". The New York Times. April 2, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- Limpus, Lowell (April 10, 1929). "Insane Hospital Loses 700 Beds by Bridge Pier". Daily News. New York. p. 138. Retrieved November 2, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Work Begins Oct. 26 On Triborough Span; Goldman Authorized by Board to Let Contracts at Once for Towers on City Property". The New York Times. October 4, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- Ruppel, Louis (June 9, 1929). "5 Cents Plus $1,400,000,000 Walker's Fare Next Fall". Daily News. New York. p. 217. Retrieved November 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Fete To Mark Start Of Triborough Span; Plans Laid for Celebration in September at Beginning of Construction". The New York Times. July 26, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "See Shipping Peril In Triborough Span; Rail and Harbor Interests Say Clearance of Harlem River Crossing Is Too Low". The New York Times. July 31, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Walker Opens Work On Triborough Span; With Silver-Plated Pick and Spade He Breaks Ground in Astoria Park". The New York Times. October 26, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Will Build Piers Of Triborough Span; The McMullen Company Gets Contract for Work Original Holder Failed to Perform". The New York Times. December 5, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "To Condemn Bridge Land; Estimate Board Fixes Procedure on Triborough Span Approaches". The New York Times. December 17, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Move To Expedite Triborough Bridge; Property Owners Delay Work by Asking Unduly High Prices". The New York Times. March 2, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Plan For 3 Bridges Here Is Approved; Bronx-Randalls Island, Queenswards Island And Hell Gate Get War Department O.K.; Bronx Kills Dam Favored; Plans For Harlem River Bridge At East 125th St. Altered And Approval Later Is Expected". The New York Times. May 1, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Washington Approves Harlem Bridge Plan; War Department Sanction Clears the Way for City's Triborough Bridge System". The New York Times. May 8, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Approves Plan for $3,000,000 Hospital Here". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 29, 1930. p. 26. Retrieved November 5, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- "Act on Triborough Bridge; Aldermen Approve $5,000,000 Bond Issue for the Project". The New York Times. July 9, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Two Boroughs File Express Road Plan; Queens and Brooklyn Submit Crosstown Boulevard Data to Estimate Board". The New York Times. July 11, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "New Bridge Approach Proposed For Bronx; Civic Groups to Confer With Bruckner on Tri-Borough Boulevard Link". The New York Times. July 26, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Urges Extension Of 2 Queens Drives; Moses Proposes to Continue Grand Central Parkway as Triborough Bridge Link". The New York Times. September 16, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Plans Studied for Brooklyn Link to Queens Span". Daily News. New York. December 28, 1931. p. 199. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Speeds Triborough Bridge; Goldman Lets $618,855 Work on Ward's Island Anchorage". The New York Times. January 7, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- "Rapid Progress Made On Triborough Bridge; One-Third of Ward's Island Anchorage Finished, Says the Report to Goldman". The New York Times. August 18, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Work Rushed by Triborough Span Builders". Daily News. New York. September 8, 1931. p. 361. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Plans $2,450,000 Bridge Contracts". The New York Times. September 5, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Bid List Opens on Piers for Tri-boro Span". Daily News. New York. October 5, 1931. p. 481. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Engineers View Work On Triborough Bridge; 15% of Construction Completed, Says City Designer". The New York Times. December 20, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Designs Submitted For Bridge Towers; Design Of Triborough Bridge Towers". The New York Times. December 7, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Piers for Tri-Borough Bridge Near Completion". Daily News. New York. February 28, 1932. p. 74. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Big Pier Ready Today On Tri-borough Bridge; First Granite Structure, in Astoria, for Support of Towers, to Be Completed". The New York Times. July 11, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Finances Of The City Were Never Better, Berry Points Out". The New York Times. February 7, 1930. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 5, 2018.

- Wantuch, Howard (July 18, 1930). "Berry Warns City's Nearing Limit of Debt". Daily News. New York. p. 62. Retrieved November 5, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- Caro 1974, pp. 340–344.

- Federal Writers' Project (1939). New York City Guide. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-60354-055-1. (Reprinted by Scholarly Press, 1976; often referred to as WPA Guide to New York City.), pp.392–94

- "Berry Would Halt $213,000,000 Work; Warns Of A Deficit". The New York Times. February 6, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Byrne Fears A Halt On Triborough Span; City Engineer Warns Work Will Be Stopped in Three Months Unless Contracts Are Let". The New York Times. March 16, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Harvey Protests Delay in Work on Tri-Boro Bridge". Daily News. New York. March 25, 1932. p. 406. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Walker And M'kee Clash Over Economy; Aldermanic Head Loses Fight to Omit Triborough Bridge From $213,000,000 Recisions". The New York Times. April 2, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "City To Push Work On Triborough Span; Approval Expected of $115,000 Rise in 1932 Budget for the New Bridg". The New York Times. May 4, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Walker To Ask R.F.C. To Give Bridge Loan And Buy City Bonds; Going to Capital Next Week to Arrange Hearing for Plea for Urgent Public Works". The New York Times. August 6, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Harvey Pleads Today for U.S. Loan on Bridge". Daily News. New York. August 11, 1932. p. 23. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "R. F. C. Prepares Liquidating Loans; Data on New York $26,000,000 Triborough Bridge Project Are Found Satisfactory". The New York Times. September 2, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "M'kee Denies Plea To Seek R.F.C. Aid; Blocks Proposals to Finish Bridge and Start Tunnel With a Federal Loan". The New York Times. October 12, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Smith Tells City How to Slash Costs". Daily News. New York. December 2, 1932. p. 294. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Bridge Before Bay Project, Urges Harvey". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 6, 1932. p. 107. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- "Seek R.F.C. Loan; Combined Civic Bodies Want Tri-borough Bridge Completed". The New York Times. January 13, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "State Board To Ask $150,000,000 Of R.F.C.; Moses Will Hold a Hearing Monday to Decide Which Projects to Recommend". The New York Times. February 4, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Harvey Hears Loan Report with Delight". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. February 12, 1932. p. 3. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- "Mayor Bans Loans From R.F.C. For City; Financing Will Continue as in Past, He Says on Proposal for Real Estate Help". The New York Times. February 15, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "City Bridge Board Sought By O'Brien; Mayor Wants Agency Like the Port Authority to Finance Triborough Project". The New York Times. March 29, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Lehman To Demand Action On Charter; Message Is Expected When the Desmond-Moffat Proposal Is Taken Up Today". The New York Times. April 5, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Signs Tri-Borough Bridge Bills". The New York Times. April 8, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Lehman OKs Bill for 3-Boro Span". Daily News. New York. April 9, 1933. p. 133. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Battle Is Made Head Of Bridge Authority; Mayor Also Names J.A. O'Leary and F.C. Lemmerman to Board for Triborongh Span". The New York Times. April 29, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Extends Time For Bridge; War Department Sets 1936 for Completion of Triborough Section". The New York Times. April 7, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Bronx Bridge Link Bill Signed". The New York Times. April 15, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Lehman Pledges Speedy Action on Triboro Bridge". Daily News. New York. July 16, 1933. p. 357. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "$35,000,000 Sought For City Bridge; Application to R.F.C. for Triborough Loan Scheduled Within 48 Hours". The New York Times. May 24, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Requests Pour In to U.S. for Building Loans". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. May 28, 1933. p. 3. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- "Triborough Loan Expected By Aug. 31; Bridge Authority Moves to Get City to Accept Terms for $44,200,000 Grant". The New York Times. August 19, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "City Can Give No Jobs On Triborough Span; Contractors Mast Hire 18,000 Needed for Project Under Terms of Federal Loan". The New York Times. August 22, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "City Votes Work For 18,000 Men On Triboro Span". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 25, 1933. p. 1. Retrieved November 6, 2018 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- "$79,500,000 Is Ready For City ProjectS; Officials Sign Compacts for Loans for Triborough Span and Midtown Tunnel". The New York Times. September 2, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "City Acquires Land For Triborough Span; Board of Estimate Expected to Remove Last Obstacle to Project on Monday". The New York Times. September 16, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "$10,399,810 Works For Bridge Listed; Contracts Prepared and Some Approved for New Phases of Triborough Span Project". The New York Times. January 4, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.

- "Triborough Bridge Bids Opened". The New York Times. January 7, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 6, 2018.