Tsushima Island

Tsushima Island (Japanese: 対馬, Hepburn: Tsushima) is an island of the Japanese archipelago situated in-between the Tsushima Strait and Korea Strait, approximately halfway between Kyushu and the Korean Peninsula.[3][4] The main island of Tsushima, once a single island, was divided into two in 1671 by the Ōfunakoshiseto canal and into three in 1900 by the Manzekiseto canal. These canals were driven through isthmuses in the center of the island, forming "North Tsushima Island" (Kamino-shima) and "South Tsushima Island" (Shimono-shima). Tsushima also incorporates over 100 smaller islands, many tiny. The name Tsushima generally refers to all the islands of the Tsushima archipelago collectively.[5] Administratively, Tsushima Island is in Nagasaki Prefecture.

Native name: 対馬 | |

|---|---|

Satellite photo of Tsushima island | |

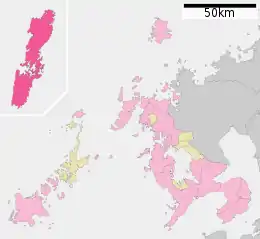

Map of Nagasaki Prefecture with Tsushima Island in red | |

Tsushima  Tsushima | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Tsushima Strait, Korea Strait |

| Coordinates | 34°25′N 129°20′E |

| Adjacent to | Tsushima Strait |

| Area | 708.7 km2 (273.6 sq mi)[1] |

| Coastline | 915 km (568.6 mi) |

| Highest elevation | 649 m (2129 ft) |

| Highest point | Mt. Yatate[2] |

| Administration | |

| Prefectures | Nagasaki Prefecture |

| City | Tsushima |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 29,577 (Sep 2020.) |

| Pop. density | 42/km2 (109/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Japanese people |

The island group measures about 70 km (43 mi) by 15 km (9 mi) and had a population of about 34,000 as of 2013. The main islands (that is, the "North" and "South" islands, and the thin island that connects them) are the largest coherent satellite island group of Nagasaki Prefecture and the eighth-largest in Japan. The city of Tsushima, Nagasaki lies on Tsushima Island and is divided into six boroughs.[6]

Geography

Tsushima Island is located west of the Kanmon Strait at a latitude between Honshu and Kyushu of the Japanese mainland. The Korea Strait splits at the Tsushima Island Archipelago into two channels; the wider channel, closer to the mainland of Japan, is the Tsushima Strait. Ōfunakoshi-Seto and Manzeki-Seto, the two canals built in 1671 and 1900 respectively, connect the deep indentation of Asō Bay (浅茅湾) to the east side of the island. The archipelago comprises over 100 smaller islets in addition to the main island.

Tsushima is the closest Japanese territory to the Korean Peninsula, lying approximately 50 km from Busan.[7] On a clear day, the hills and mountains of the Korean peninsula are visible from the higher elevations on the two northern mountains. The nearest Japanese port, Iki, situated on Iki Island within the Tsushima Basin, is also 50 km away.[8] Tsushima Island and Iki Island are collectively within the borders of the Iki–Tsushima Quasi-National Park,[6] designated as a nature preserve and protected from further development. Much of Tsushima (89%) is covered by natural vegetation and mountains.[9] Tsushima Island has many mountains such as the Mt. Ohira, Mt. Yatate, Mt. Hokogatake, Mt. Koyasan, Mt. Ontake, Mt. Gogen.[10]

The Government of Japan administers Tsushima Island as a single entity despite the artificial waterways that have separated it into two islands. The northern area is known as Kamino-shima (上島), and the southern island as Shimono-shima (下島). Both sub-islands have a pair of mountains. Shimo-no-shima has Mount Yatate (矢立山), standing 649 m (2,129 ft) high,[2] and Ariake-yama (有明山), at 558 m (1,831 ft) high.[2] Kami-no-shima has Mi-take (御嶽), 487 m (1,598 ft).[2] The two main sections of the island are now joined by a combination bridge and causeway.[11][12] The island has a total area of 696.26 km2 (268.83 sq mi).

Asō Bay from Shiroyama

Asō Bay from Shiroyama Top of Mount Shiroyama and Asō Bay in Tsushima

Top of Mount Shiroyama and Asō Bay in Tsushima Aerial photo of Asō Bay and around Ochikiri Island (1977)

Aerial photo of Asō Bay and around Ochikiri Island (1977) Tsushima Island, located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan

Tsushima Island, located in Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan

Climate

Tsushima has a marine humid subtropical climate strongly influenced by monsoon winds. The average temperature is 15.8 °C (60.4 °F),[13] and the average yearly precipitation is 2,132.6 mm.[13] The highest temperature ever recorded on the island is 36.6 °C (97.9 °F), on 20 August 2013, and the lowest −6.8 °C (19.8 °F), in 1895.[14] Throughout most of the year, Tsushima is 1–2 °C cooler than the city of Nagasaki.[13][15] The island's rainfall is generally higher than that of the main islands of Japan; this is attributed to the difference in their size. Because Tsushima is small and isolated, it is exposed on all sides to moist marine air, which releases precipitation as it ascends the island's steep slopes. Continental monsoon winds carry loess, a dust which is a highly fertile mix of clay and sand, from China in the spring and cool the island in the winter.[6]

| Climate data for Izuhara, Tsushima (1991−2020 normals, extremes 1886−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 19.8 (67.6) |

21.3 (70.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

27.8 (82.0) |

32.0 (89.6) |

32.9 (91.2) |

36.9 (98.4) |

36.8 (98.2) |

34.6 (94.3) |

30.2 (86.4) |

26.9 (80.4) |

22.3 (72.1) |

36.9 (98.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.2 (48.6) |

10.5 (50.9) |

13.6 (56.5) |

18.1 (64.6) |

22.2 (72.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.0 (86.0) |

26.5 (79.7) |

22.3 (72.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

11.6 (52.9) |

19.5 (67.1) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.0 (42.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

14.2 (57.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.3 (70.3) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.8 (80.2) |

23.4 (74.1) |

18.7 (65.7) |

13.3 (55.9) |

8.0 (46.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2.5 (36.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

6.3 (43.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

14.4 (57.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

20.6 (69.1) |

15.3 (59.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

12.7 (54.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −7.7 (18.1) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

4.8 (40.6) |

6.2 (43.2) |

12.2 (54.0) |

13.6 (56.5) |

8.8 (47.8) |

0.7 (33.3) |

−2.7 (27.1) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

−8.6 (16.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 80.1 (3.15) |

94.7 (3.73) |

172.3 (6.78) |

218.4 (8.60) |

241.2 (9.50) |

294.4 (11.59) |

370.5 (14.59) |

326.4 (12.85) |

235.5 (9.27) |

120.8 (4.76) |

100.6 (3.96) |

68.0 (2.68) |

2,302.6 (90.65) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.4 | 6.8 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 8.2 | 10.8 | 11.6 | 10.5 | 9.0 | 5.6 | 6.6 | 6.3 | 99.8 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1 cm) | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 61 | 62 | 65 | 68 | 72 | 82 | 83 | 81 | 78 | 70 | 68 | 63 | 71 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 147.6 | 143.5 | 161.5 | 183.1 | 199.2 | 136.3 | 136.1 | 160.4 | 131.1 | 161.1 | 149.0 | 153.9 | 1,862.8 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[16][17] | |||||||||||||

Ecology

Fauna

The island's fauna include leopard cat, Japanese marten, Siberian weasel, and rodents.[18] Otters were discovered to be living on Tsushima in February 2017.[19] Migrating birds that stop over on the island include hawks, harriers, eagles, and black-throated loons. Forests, covering 90% of the island, consist of broad-leafed evergreens, conifers, and deciduous trees including cypress. Honey bees are common, with many used to produce commercial honey.[20] The Tsushima Island pitviper (Gloydius tsushimaensis) is a venomous snake endemic to the Tsushima Island.[21] The islands have been recognised as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because they support populations of Japanese wood pigeons and Pleske's grasshopper warblers.[22]

Tsushima Reef, located in the bay between Tsushima and Iki Island, is the northernmost coral reef in the world, surpassing the Iki Island reef discovered in 2001.[23] It is dominated by cool-tolerant stony or Scleractinian Favia corals but the observed settling of tropical Acropora coral is expected to provide an ongoing indicator for continuing global warming.[24]

Flora

The whole island is covered in forest and there are few plains. There are Yoshino cherry and Chionanthus retusus.

Yoshino cherry

Yoshino cherry Chionanthus retusus

Chionanthus retusus

Economy

Industry

According to a 2000 census, 23.9% of the local population is employed in primary industries while 19.7% and 56.4% of the population are employed in secondary and tertiary industries, respectively. Of these economic activities, fishing amounts to 82.6% of the primary industry, with much of it dedicated to catching squid on the eastern coast of the island. The number of employees in the primary industries has been decreasing, while employee growth in the secondary and tertiary industries has been increasing.

Tourism

Tourism, targeting mainly South Koreans, has recently made a great contribution to the islands' economy. The number of Korean tourists to the island increased greatly after the launching of a high-speed ferry service from Busan to the island in 1999. In 2008, 72,349 Koreans visited the island. Due to a drop in the value of the won, the number fell to 45,266 in 2009. Korean tourists generate an estimated ¥2.1 billion in revenue for the local economy and generate about 260 jobs on the island.[25]

The island expected around 200,000 visitors from Korea in 2013, surpassing the number of visitors from within Japan for the first time.[26] However, a summer pageant focused on a historical event involving Korean emissaries was cancelled that same year.[26][27] In 2018, 90% of visitors to Tsushima were from South Korea; however, diplomatic issues between Japan and South Korea led to an 88% decrease (1.7 million fewer visitors) in Korean visitors in 2019. Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has further reduced and limited tourism.[28]

Tsushima has been gaining popularity as a tourist destination thanks in large part to the samurai action-adventure stealth game Ghost of Tsushima that was released in 2020, with visitors keen to see some of the places featured in the game, as well as discover what the island is like in "real life". This includes trying local culinary specialties such as rokube noodles, ishiyaki, tonchan and anago conger eel.[29]

Tsushima city

Tsushima city was established on 1 March 2004, from the merger of six towns on Tsushima Island: Izuhara, Mitsushima, and Toyotama (all from Shimoagata District), and Mine, Kamiagata, and Kamitsushima (all from Kamiagata District). It is the only city of Tsushima Subprefecture and encompasses the whole island.

Transportation

Tsushima Airport has flights to Fukuoka Airport (on All Nippon Airways and Oriental Air Bridge) and Nagasaki Airport (Oriental Air Bridge only).

There are ferries to Izuhara port, such as Iki via Hakata port in Fukuoka.

History

Ancient and classical period

In Japanese mythology, Tsushima was one of the eight original islands created by the Shinto deities Izanagi and Izanami. Archaeological evidence suggests that Tsushima was already inhabited by settlers from the Japanese archipelago and Korean Peninsula from the Jōmon period to the Kofun period. The Records of the Three Kingdoms, a Chinese historical text, describes a country called Duì hǎi guó (Chinese: 對海國; Japanese pronunciation: Tsuikai-koku) with a population of more than one thousand households, which is commonly identified with Tsushima. It was one of the about 30 that composed the Yamatai union countries.[30] These families exerted control over Iki Island, and established trading links with Yayoi Japan. Since Tsushima had almost no land to cultivate, islanders earned their living by fishing and trading.

Since the beginning of the early sixth century, Tsushima has been an official province of Japan, known as Tsushima Province (today Tsushima, Nagasaki.)

Under the Ritsuryō system, Tsushima became a province of Japan. This province was linked with Dazaifu, the political and economical center of Kyūshū, as well as the central government of Japan. Due to its strategic location, Tsushima played a major role in defending Japan against invasions from the Asian continent and developing trade lines with Baekje and Silla of Three Kingdoms of Korea. After Baekje, which had been aided by Yamato Japan, was defeated in 663 by Sillan and Tang Chinese forces at the Battle of Baekgang, Japanese border guards were sent to Tsushima and Kaneda Castle was constructed on the island.

Tsushima Province was controlled by officials called Tsushima no kuni no miyatsuko (対馬国造) until the Nara period, and then by the Abiru clan until the middle of the 13th century. The role and title of "Governor of Tsushima" was exclusively held by the Shōni clan for generations. However, since the Shōni actually resided in Kyūshū, it was the Sō clan, known subjects of the Shōni, who actually exerted control over these islands. The Sō clan governed Tsushima until the late 15th century.

Feudal period

Tsushima was an important trade center during this period. After the Toi invasion, private trade started between Goryeo, Tsushima, Iki Island, and Kyūshū, but halted during the Mongol invasions of Japan between 1274 and 1281. The Goryeosa, a history of the Goryeo dynasty, mentions that in 1274, Korean troops of the Mongol army led by Kim Bang-gyeong killed a great number of people on the islands.

Tsushima became one of the major bases of the Wokou, Japanese pirates, also called wakō, along with Iki and Matsuura. Due to repeated pirate raids, the Goryeo and Joseon at times placated the pirates by establishing trade agreements as well as negotiating with the Ashikaga shogunate and its deputy in Kyūshū and at other times used force to neutralize the pirates. In 1389, General Pak Wi of Goryeo wiped out Wokou on the island of Tsushima.

On 19 June 1419, the recently abdicated king Taejong of Joseon sent general Yi Jongmu to an expedition to Tsushima island to clear it of the Wokou pirates, using a fleet of 227 vessels and 17,000 soldiers, known in Japanese as the Ōei Invasion. After suffering casualties in an ambush, the Korean Army negotiated a ceasefire and withdrew on 3 July 1419.[31][32] In 1443, the Daimyō of Tsushima, Sō Sadamori proposed the Treaty of Gyehae. The number of trade ships from Tsushima to Korea was decided by this treaty, and the Sō clan monopolized the trade with Korea.[33]

In 1510, Japanese traders initiated an uprising against Joseon's stricter policies on Japanese traders from Tsushima and Iki coming to Busan, Ulsan and Jinhae to trade. The So Clan supported the uprising, but it was soon crushed. The uprising later came to be known as the "Disturbance of the Three Ports" (三浦の乱 (Sanbo-No-Ran) in Japan and 삼포왜란 (三浦倭亂, Sampo Waeran) in Korea). Trade resumed under the direction of King Jungjong in 1512, but only under strictly limited terms, and only twenty-five ships were allowed to visit Joseon annually.[34]

In the late 16th century, Japanese leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi united the various feudal lords (daimyō) under his command and in 1587, Hideyoshi confirmed the Sō clan's possession of Tsushima. Sō Yoshitoshi (宗 義智, 1568 – 31 January 1615) was a Sō clan daimyō (feudal lord) of the island domain of Tsushima. Planning to unite all factions with a common cause, Hideyoshi's coalition attacked Joseon Korea, leading to the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598). Tsushima was the main naval base for this invasion, and in continuing support of the war, large numbers of Korean prisoners were transported to Tsushima until 1603.

In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu established a new shogunate; and Sō Yoshitoshi was officially granted Fuchū Domain (100,000 koku) in Tsushima Province.[35]

The Tsushima-Fuchū Domain shipyard was built in 1663 CE. There are still ruins of the shipyard on the island.

After Japan's attempts at conquest failed, peace was re-established between the two nations. Once again, the islands became a port for merchants. Both the Joseon Dynasty and the Tsushima-Fuchū Domain sent their trading representatives to Tsushima, governing trade until 1755.

The island was described by Hayashi Shihei in Sangoku Tsūran Zusetsu, which was published in 1785. It was identified as part of Japan.[36]

In 1811, for cost reduction, representatives of the Tokugawa shogunate met at Tsushima with ambassadors from the Joseon king (Joseon Tongsinsa).[37]

Until the Meiji, Tsushima was a frontier between Japan and Korea, heavily dependent on the trade with Korea, with unique institutions/systems of trade which strongly resembled those of Korean, not Japanese, institutions - for instance, measurement system for the taxation of land in Japan, is determined by the production of kokus of rice. Tsushima had a low production of rice, so it was permitted to use a unique survey system (Kendaka (間高)) by Tokugawa shogunate. Because it had originated in China Land Survey System (間尺法), it was similar to the system of Korea - gyeolbu (結負制); Tsushima law resembled Korean law in its calculation of finances. "Unfree labor" or slavery for fixed periods of time, always rare in any form in the rest of Japan, existed as an established institution, often as a form of punishment, in Tsushima as it did in Korea. The Tsushima han owned a 33 hectares (82 acres) place of residence in Busan, according to Murai Shosuke, the Japanese was given the title from the Joseon dynasty is called "marginal men", was responsible for security in this residential area.[38] Lewis also cites the official preparations of Sō Yoshitoshi listing some 1,000 Koreans as guides in preparation for Hideyoshi's invasions of Korea to support a "zone of ambiguous boundary qualities" aspect of Tsushima.[38] The islanders spoke the Tsushima dialect and their daily customs, social structure, and economic interactions were in Japanese, with exception of loanwords from Korean in their dialect.[39]

Modern period

In an episode now known as the Tsushima incident, the Imperial Russian Navy tried to appropriate the island by establishing a base on the island in 1861. In 1860 this plan had been made by Vice Admiral Ivan Likhachev, commanding the Russian squadron in the waters of Japan and the Commander of the Possadnick, Birilev in co-operation with the Russian Consul at Hakodate Goshkevitch. The plan had been discussed with high authorities at St Petersburg who had given the green light to proceed with it. If the plan would miscarry they would deny all knowledge about it.[40] The Russians were forced to withdraw by Vice Admiral John Hope, Commanding the British ships in the waters of Japan on orders of Sir Rutherford Alcock, representing Britain in Japan and the British government. Support at St Petersburg was given by the British Envoy Lord Napier and the Dutch Envoy Baron Gevers[41]

As a result of the abolition of the han system, the Tsushima Fuchu domain became part of Izuhara Prefecture in 1871. In the same year, Izuhara Prefecture was merged with Imari Prefecture, which was renamed Saga Prefecture in 1872. Tsushima was transferred to Nagasaki Prefecture in 1872, and its districts of Kamiagata (上県) and Shimoagata (下県) were merged to form the modern city of Tsushima. This change was part of widespread reforms within Japan which started after 1854. Japan was at this time becoming a modern nation state and regional power, with widespread changes in government, industry, and education.

After the First Sino-Japanese War ended with the Treaty of Shimonoseki, Japan felt humiliated when the Triple Intervention of the three great powers of Germany, France, and Russia forced it to return the valuable Liaodong Peninsula to China under threat of force. Consequently, the Japanese leadership correctly anticipated that a war with Russia or another Western imperial power was likely. Between 1895 and 1904, the Imperial Japanese Navy blasted the Manzeki-Seto canal 25 metres (82 feet) wide and 3 metres (9.8 feet) deep; it was later expanded to 40 metres (130 feet) wide and 4.5 metres (14.8 feet) deep through a mountainous rocky isthmus of the island between Asō Bay to the west and Tsushima Strait to the east, technically dividing the island into three islands.[42] Strategic concerns explain the scope and funding of the canal project by Japan during an era when it was still struggling to establish an industrial economy. The canal enabled the Japanese to move transports and warships quickly between their main naval bases in the Seto Inland Sea (directly to the east) via the Kanmon and Tsushima Strait into the Korea Strait or to destinations beyond in the Yellow Sea.

An imperial ordinance in July 1899 established Izuhara, Sasuna, and Shishimi as open ports for trading with the United States and the United Kingdom.[43]

During the Russo-Japanese War in 1905, the Russian Baltic Fleet under Admiral Rozhestvensky, after making an almost year-long trip to East Asia from the Baltic Sea, was crushed by the Japanese under Admiral Togo Heihachiro at the Battle of Tsushima.[44] The Japanese third squadron (cruisers) began shadowing the Russian fleet off the tip of the south island and followed it through the Tsushima Strait where the main Japanese fleet awaited. The battle began at slightly east-northeast of the northern island around midday, and ended to its north a day later when the Japanese surrounded the Russian Fleet. Japan won a decisive victory.

From 1948 to 1949, due to the Jeju uprising, and its resulting suppression and massacre by anti-communist Korean forces, thousands of Jeju residents fled to Japan via Tsushima.[45]

In 1950, the South Korean government asserted sovereignty over the island based on "historical claims".[46] Korea-US negotiations about the Treaty of San Francisco made no mention of Tsushima Island.[47] After this, the status of Tsushima as an island of Japan was re-confirmed.[48] While the South Korean government has since relinquished claims on the island, some Koreans (including some members of the Korean parliament) have periodically attempted to dispute the ownership of the island.

In 1973, one of the transmitters for the OMEGA-navigation system was built on Tsushima. It was dismantled in 1998.

Today, Tsushima is part of Nagasaki Prefecture, Japan. On 1 March 2004, the six towns on the island – Izuhara, Mitsushima, Toyotama, Mine, Kamiagata, and Kamitsushima – were merged to create the city of Tsushima. About 700 Japan Self-Defense Forces personnel are stationed on the island to watch the local coastal and ocean areas.[25]

Historical dispute

Tsushima is administered by Nagasaki Prefecture. The South Korean city of Changwon also asserts ownership of the island,[49] calling it Daemado (Korean pronunciation: [te:ma.do]; Korean: 대마도; Hanja: 對馬島; RR: Daemado; MR: Taemado), the Korean reading of the characters used in the Japanese name (Japanese: 對馬).[50]

Archaeological evidence suggests that Tsushima was already inhabited by settlers from the Japanese archipelago from the Jōmon period (14,000 BCE) to the Kofun period (300 CE). Also, according to the Sanguo Zhi in the 3rd century Tsushima was Tsuikai-koku and one of the 30 that composed the Yamataikoku union countries (邪馬台国).[30] This island, as Tsushima Province, has been ruled by Japanese governments since the Nara period (710 CE).[51] According to the Korean history book Samguk Sagi written in 1145, Tsushima is ruled by the Japanese from CE 400.[52]

On 19 June 1419, Japan repelled the Ōei Invasion of king Sejong of Joseon. He sent general Yi Jong-mu to an expedition to Tsushima island to clear it of the Wokou pirates, using a fleet of 227 vessels and 17,000 soldiers. The Joseon invaders suffered casualties in an ambush and the Korean Army negotiated a ceasefire and withdrew on 3 July 1419.[31] Afterwards, in diplomatic exchanges, the lords of Tsushima would be granted exclusive trading privileges with Joseon in exchange for maintaining control and order of pirate threats originating from the island which was the very reason for the original expedition.[53]

The Tsushima Fuchu domain became part of Izuhara Prefecture in 1871. In the same year, Izuhara Prefecture merged with Imari Prefecture, which was renamed Saga Prefecture on 29 May 1872. The island provinces of Tsushima and Iki were merged with the western half of the former province of Hizen and became modern-day Tsushima, Nagasaki Prefecture in 1872.[54]

The South Korean government made a claim in 1948, but it was rejected by US Gen. MacArthur, the then-Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers (SCAP) in 1949. On 19 July 1951, the South Korean government agreed that the earlier demand for Tsushima had been dropped by the South Korean government with regard to the Japanese peace treaty negotiations.[55]

The status of Tsushima as an island of Japan was re-confirmed in 1965.[48]

In 2008, Yasunari Takarabe, incumbent Mayor of Tsushima rejected the South Korean territorial claim: "Tsushima has always been Japan. I want them to retract their wrong historical perception. It was mentioned in the Gishiwajinden (魏志倭人伝) [a chapter of volume 30 of Book of Wei in the Chinese Records of the Three Kingdoms] as part of Wa (Japan). It has never been and cannot be a South Korean territory."[56]

Notable people from Tsushima

- Tsuyoshi Shinjo - Baseball player

- Misia - Japanese singer

- Sō Yoshitoshi - Sō clan

Popular culture

Tsushima Island is the setting for the PlayStation 4 game Ghost of Tsushima, released by Sucker Punch Productions in 2020.[57] In response to the popularity of the game, Nagasaki Prefecture used it to promote tourism to Tsushima.[58][59] After a typhoon damaged a Shinto torii gate on the island in September 2020, fans of the game helped raise money to restore it.[60] The creative leads of the game, Nate Fox and Jason Connell, were named as tourism ambassadors to the island in March 2021, as those "who has spread the name and history of Tsushima through their works".[61] On March 25, 2021, Sony Pictures and PlayStation Productions announced the development of a film adaptation of the game.[62]

See also

- History of Japan

- Oei Invasion

- Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598)

- Tsushima Island dispute

- Tsushima Subprefecture

- Korea Strait

References

- 市勢要覧(資料編) Archived 12 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine (in Japanese)—Data about Tsushima

- (in Japanese) 国土交通省国土地理院 九州地方測量部「長崎県山岳標高」 Archived 15 January 2008 at the Wayback Machine - Kyushu Regional Survey Department, Geographical Survey Institute, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism in Japan

- "34.416667,129.333333 - Map of Cities in 34.416667,129.333333 - MapQuest". www.mapquest.com. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- "Tsushima | archipelago, Japan". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

-

For example:

"Tsushima". The New Encyclopaedia Britannica: Macropaedia. Vol. 10 (15 ed.). Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1983. ISBN 9780852294000. Retrieved 28 October 2020.

Tsushima, archipelago, Nagasaki Prefecture (ken), Japan, in the Korea Strait separating Japan and Korea.

- "A Profile of Tsushima shi (Tsushima City)". www.city.tsushima.nagasaki.jp. Archived from the original on 10 September 2020. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- "Google Maps". Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- "Google Maps". Retrieved 2 May 2008.

- "Asahi.com article on Tsushima". Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 17 June 2006.

- "Interactive Map of Tsushima". Tsushima. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- "Aerial view of the junction between the two islands of Tsushima Island". Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 23 June 2005.

- Water level view of the junction between the two islands of Tsushima Island

- Meteorologic data in Izuhara (厳原), Tsushima by Japan Meteorological Agency

- Meteorologic data in Izuhara (厳原), Tsushima by Japan Meteorological Agency - most ~ 10th largest value on record

- Meteorologic data in Nagasaki (長崎) by Japan Meteorological Agency

- 観測史上1~10位の値(年間を通じての値). JMA. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). JMA. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- Tatara, M.; Doi, T. (1994). "Comparative analyses on food habits of Japanese marten, Siberian weasel and leopard cat in the Tsushima islands, Japan". Ecological Research. 9 (1): 99–107. doi:10.1007/BF02347247. S2CID 19530021.

- "Wild otter filmed alive in first Japan sighting since 1979". The Japan Times. 17 August 2017. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Nicol, C.W., "Hark ye to the Donkey's Ears", Japan Times, 7 March 2010, p. 12. Archived 16 July 2012 at archive.today

- Gloydius tsushimaensis at the Reptarium.cz Reptile Database. Accessed 14 February 2015.

- "Tsushima islands". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- Gammon, Crystal (July 2012). "World's Northernmost Coral Reef Discovered in Japan". livescience.com. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- Hiroya Yamano et al., in the on-line journal Geology, 12 July 2012, reported by Joost DeVries at Reefbuilders and at Advanced Aquarist

- Kaneko, Maya, (Kyodo News) "Tsushima's S. Koreans: guests or guerrillas?", Japan Times, 5 March 2010, p. 3. Archived 6 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Fackler, Martin (3 June 2013). "An Icon and a Symbol of Two Nations' Anger". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- "Official announcement of Tsushima tourism association". Archived from the original on 20 August 2013. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- Wolfe, Dan Kopf, Daniel. "The Japan tourism explosion stalled in 2019 because of a spat with South Korea". Quartz. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Wallin, Lisa, "What to Eat When You’re on Tsushima Island", Japanese Food Guide

- zhulang.com Archived 12 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "朝鮮王朝実録世宗4卷1年7月3日" Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty King SejongVol.4 July 3

- "朝鮮王朝実録世宗4卷1年7月9日" Veritable Records of the Joseon Dynasty King SejongVol.4 July 9 "세종 4권, 1년(1419 기해 / 명 영락(永樂) 17년) 7월 9일(임자) 5번째기사이원이 막 돌아온 수군을 돌려 다시 대마도 치는 것이 득책이 아님을 고하다"

- Tsushima tourist Association WEB site Archived 17 September 2018 at the Wayback Machine"1443 嘉吉条約(発亥約定)- 李氏朝鮮と通交条約である嘉吉条約を結び、歳遣船の定数を定める。これにより、宗家が朝鮮貿易の独占的な地位を占めるようになる。"

- dictionary.goo.ne.jp

- Papinot, Jacques. (2003). Nobiliare du Japon -- Sō, p. 56; Papinot, Jacques Edmond Joseph. (1906). Dictionnaire d'histoire et de géographie du Japon.

- Klaproth, Julius. (1832). San kokf tsou ran to sets, ou Aperçu général des trois royaumes, p. 96; excerpt, "... et vis-à-vis de l'île de Toui ma tao (Tsou sima) qui fait partie du Japon ...."

- Walraven, Boudewijn (2007). Korea in the Middle: Korean Studies and Area Studies : Essays in Honour of Boudewijn Walraven. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 359–361. ISBN 978-90-5789-153-3.

- Lewis, James B. (2003). Frontier Contact Between Choson Korea and Tokugawa Japan. Taylor & Francis. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-203-98732-2.

- Lewis, James B. (2003). Frontier Contact Between Choson Korea and Tokugawa Japan. Taylor & Francis. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-203-98732-2.

- Russian documents in the Central State Navy Archive St Petersburg, fund 410 and Morskoi Sbornik, 1913

- Public Record Office Kew, Foreign Office 262 and 410; National Archive, The Hague, Archive of Consulat Yokohama No. 3 and 4

- "地理院地図 / GSI Maps|国土地理院". maps.gsi.go.jp. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- US Department of State. (1906). A digest of international law as embodied in diplomatic discussions, treaties and other international agreements (John Bassett Moore, ed.), Vol. 5, p. 759.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 351.

- "[Special Features Series: April 3 Jeju Uprising, Part II] The April 3 Exodus". english.hani.co.kr. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- "U.S. State Department, Report from the Office of Intelligence Research: Korea´s Recent Claim to the Island of Tsushima (prepared on March 30, 1950)"; retrieved 2 April 2013.

- "Memorandum of Conversation, by the Officer in Charge of Korean Affairs in the Office of Northeast Asian Affairs (Emmons)," Archived 7 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine Foreign Relations 1951, Vol. VI, pp. 1202-1203; excerpt, "Mr. Dulles noted that paragraph 1 of the Korean Ambassador's communication made no reference to the island of Tsushima and the Korean Ambassador agreed that this had been omitted."

- US Bureau of the Census (1965). Foreign Commerce and Navigation of the United States, p. lv.

- "Ordinance of Day of Daemado in Changwon". Enhanced Local Laws and Regulations Information System (in Korean). 28 December 2012. Archived from the original on 19 September 2019. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "Japan ponders law banning foreigners buying land near to military sites". South China Morning Post. 29 October 2013.

- "ながさきのしま|長崎のしま紹介【対馬】|".

- 三国史記(Samguk Sagi) 巻三 新羅本記 三 實聖尼師今条 "七年、春二月、王聞倭人於対馬島置営貯以兵革資糧、以謀襲我 我欲先其末発 練精兵 撃破兵儲"

- "Annals of King Sejong Vol.7 1st leap month 10". sillok.history.go.kr. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- Frédéric, Louis (2002). Japan Encyclopedia. Harvard University Press. p. 780. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5.

- The Foreign Relations Series (FRUS) 1951 VolumeVI P1203. Subject:Japanese Peace Treaty Archived 7 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine, Participants:Dr. Yu Chan Yang, Korean Ambassador and John Foster Dulles U.S. Ambassador

- "【動画】竹島問題で韓国退役軍人が抗議 対馬市民反発で現場騒然". The Nagasaki Shimbun. 24 July 2008. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2011.

- Stedman, Alex (15 July 2020). "'Ghost of Tsushima': How Sucker Punch Built the Massive World in 1274 Japan". Variety. Archived from the original on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

- Ramsey, Robert (20 July 2020). "Actual Tsushima Tourism Page Partners with Ghost of Tsushima". Push Square. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Kelly, Katy (31 July 2020). "Venture through real-life locations from 'Ghost of Tsushima' with this handy tourism website". Japan Today. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- Nelva, Giuseppe (21 December 2020). "Ghost of Tsushima Fans Help Restore Torii Toppled by Typhoon in Real-World Tsushima". Twinfinite. Retrieved 22 December 2020.

- Scullion, Chris (5 March 2021). "Ghost of Tsushima devs to be made permanent ambassadors of the real island". Video Games Chronicle. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- Kroll, Justin (25 March 2021). "Sony And PlayStation Productions Developing 'Ghost of Tsushima' Movie With 'John Wick's Chad Stahelski Directing". Deadline Hollywood. Penske Media Corporation. Archived from the original on 25 March 2021. Retrieved 24 June 2021.

Further reading

- Ian Nish, A Short History of Japan, 1968, LoCCC# 68-16796, OCLC 439631, Fredrick A. Praeger, Inc., New York, 238 pp. British title and publisher: The Story of Japan, 1968, Farber and Farber, Ltd.

- Edwin O. Reischauer, Japan: The Story of a Nation, 1970, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York. LoCCC# 77-10895. 345 pp. plus index. Previously published as Japan Past and Present, four editions, 1946–1964.

H.J. Moeshart, The Russian Occupation of Tsushima: a Stepping-stone to British Leadership in Japan, in: Ian Neary (Ed.) 'Leaders and Leadership in Japan' (Japan Library, 1996).

External links

- Tsushima City English Webpage

- A Profile of Tsushima City Archived 10 September 2020 at the Wayback Machine