US Open (tennis)

The US Open Tennis Championships is a hardcourt tennis tournament held annually in Queens, New York. Since 1987, the US Open has been chronologically the fourth and final Grand Slam tournament of the year. The other three, in chronological order, are the Australian Open, French Open and Wimbledon. The US Open starts on the last Monday of August and continues for two weeks, with the middle weekend coinciding with the US Labor Day holiday. The tournament is of one of the oldest tennis championships in the world, originally known as the U.S. National Championship, for which men's singles and men's doubles were first played in August 1881. It is the only Grand Slam that was not affected by cancellation of World War I and World War II or interrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

| Official website | |

| Founded | 1881 |

|---|---|

| Editions | 142 (2022) |

| Location | New York City United States |

| Venue | USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center (since 1978) |

| Surface | Hard – outdoors[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] (since 1978) Clay – outdoors (1975–1977) Grass – outdoors (1881–1974) |

| Prize money | US$60.1 million (2022)[1] |

| Men's | |

| Draw | S (128Q) / 64D (16Q)[lower-alpha 3] |

| Current champions | Carlos Alcaraz (singles) Rajeev Ram Joe Salisbury (doubles) |

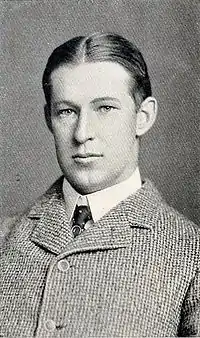

| Most singles titles | 7 Richard Sears William Larned Bill Tilden |

| Most doubles titles | 6 Mike Bryan Richard Sears Holcombe Ward |

| Women's | |

| Draw | S (128Q) / 64D (16Q) |

| Current champions | Iga Świątek (singles) Barbora Krejčíková Katerina Siniaková (doubles) |

| Most singles titles | 8 Molla Mallory |

| Most doubles titles | 13 Margaret Osborne duPont |

| Mixed doubles | |

| Draw | 32 |

| Current champions | Storm Sanders John Peers |

| Most titles (male) | 4 Bill Tilden Bill Talbert Bob Bryan |

| Most titles (female) | 9 Margaret Osborne duPont |

| Grand Slam | |

| Last completed | |

| 2022 US Open | |

The tournament consists of five primary championships: men's and women's singles, men's and women's doubles, and mixed doubles. The tournament also includes events for senior, junior, and wheelchair players. Since 1978, the tournament has been played on acrylic hardcourts at the USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, Queens, New York City. The US Open is owned and organized by the United States Tennis Association (USTA), a non-profit organization, and the chairperson of the US Open is Patrick Galbraith. Revenue from ticket sales, sponsorships, and television contracts is used to develop tennis in the United States.

This tournament, from 1971 to 2021, employed standard tiebreakers (first to 7, win by 2) in every set of a singles match.[2] Since 2022, when a match that reaches 6–all in the last possible set (the third for women and the fifth for men) an extended tiebreaker to 10 points is played. Should the tiebreaker be tied at 9-all, whoever scores two straight points wins it.

History

1881–1914: Newport Casino

The tournament was first held in August 1881 on grass courts at the Newport Casino in Newport, Rhode Island, which is now home to the International Tennis Hall of Fame. That year, only clubs that were members of the United States National Lawn Tennis Association (USNLTA) were permitted to enter.[3] Richard Sears won the men's singles at this tournament, which was the first of his seven consecutive singles titles.[4] From 1884 through 1911, the tournament used a challenge system whereby the defending champion automatically qualified for the next year's final, where he would play the winner of the all-comers tournament.

In the first years of the U.S. National Championship, only men competed and the tournament was known as the U.S. National Singles Championships for Men. In September 1887, six years after the men's nationals were first held, the first U.S. Women's National Singles Championship was held at the Philadelphia Cricket Club. The winner was 17-year-old Philadelphian Ellen Hansell. In that same year, the men's doubles event was played at the Orange Lawn Tennis Club in South Orange, New Jersey.[5]

The women's tournament used a challenge system from 1888 through 1918, except in 1917. Between 1890 and 1906, sectional tournaments were held in the east and the west of the country to determine the best two doubles teams, which competed in a play-off for the right to compete against the defending champions in the challenge round.[6]

The 1888 and the 1889 men's doubles events were played at the Staten Island Cricket Club in Livingston, Staten Island, New York.[7] In the 1893 Championship, the men's doubles event was played at the St. George Cricket Club in Chicago.[8][9][10] In 1892, the US Mixed Doubles Championship was introduced and in 1899 the US Women's National Doubles Championship.

In 1915, the national championship was relocated to the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills, Queens, New York City. The effort to relocate it to New York City began as early as 1911 when a group of tennis players, headed by New Yorker Karl Behr, started working on it.[11]

1915–1977: West Side Tennis Club

In early 1915, a group of about 100 tennis players signed a petition in favor of moving the tournament. They argued that most tennis clubs, players, and fans were located in the New York City area and that it would therefore be beneficial for the development of the sport to host the national championship there.[12] This view was opposed by another group of players that included eight former national singles champions.[13][14] This contentious issue was brought to a vote at the annual USNLTA meeting on February 5, 1915, with 128 votes in favor of and 119 against relocation.[15][16][17] In August 1915, the men's singles tournament was held in the West Side Tennis Club, Forest Hills in New York City for the first time while the women's tournament was held in Philadelphia Cricket Club in Chestnut Hill, Philadelphia (the women's singles event was not moved until 1921). From 1917 to 1933, the men's doubles event was held in Longwood Cricket Club in Chestnut Hill, Massachusetts. In 1934, both men's and women's doubles events were held in Longwood Cricket Club.[18]

From 1921 through 1923, the men's singles tournament was played at the Germantown Cricket Club in Philadelphia.[19] It returned to the West Side Tennis Club in 1924 following completion of the 14,000-seat Forest Hills Stadium.[6] Although many already regarded it as a major championship, the International Lawn Tennis Federation officially designated it as one of the world's major tournaments commencing in 1924.[20] At the 1922 U.S. National Championships, the draw seeded players for the first time to prevent the leading players from playing each other in the early rounds.[21][22] From 1935 to 1941 and from 1946 to 1967, the men's and women's doubles were held at the Longwood Cricket Club.[23]

Open era

The open era began in 1968 when professional tennis players were allowed to compete for the first time at the Grand Slam tournament held at the West Side Tennis Club. The previous U.S. National Championships had been limited to amateur players. Except for mixed doubles, all events at the 1968 national tournament were open to professionals. That year, 96 men and 63 women entered, and prize money totaled $100,000. In 1970, the US Open became the first Grand Slam tournament to use a tiebreaker to decide a set that reached a 6–6 score in games. From 1970 through 1974, the US Open used a best-of-nine-point sudden-death tiebreaker before moving to the International Tennis Federation's (ITF) best-of-twelve points system.[4] In 1973, the US Open became the first Grand Slam tournament to award equal prize money to men and women, with that year's singles champions, John Newcombe and Margaret Court, receiving $25,000 each.[4] From 1975, following complaints about the surface and its impact on the ball's bounce, the tournament played on clay courts instead of grass. This was also an experiment to make it more "TV friendly". The addition of floodlights allowed matches to be played at night.[24][25]

Since 1978: USTA National Tennis Center

In 1978, the tournament moved from the West Side Tennis Club to the larger and newly constructed USTA National Tennis Center in Flushing Meadows, Queens, 3 miles (4.8 km) to the north. The tournament's court surface also switched from clay to hard. Jimmy Connors is the only individual to have won US Open singles titles on three surfaces (grass, clay, and hard), while Chris Evert is the only woman to win US Open singles titles on two surfaces (clay and hard).[4]

The US Open is the only Grand Slam tournament that has been played every year since its inception.[26]

During the 2006 US Open, the complex was renamed to "USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center" in honor of Billie Jean King, a four-time US Open singles champion and women's tennis pioneer.[27]

From 1984 through 2015, the US Open deviated from traditional scheduling practices for tennis tournaments with a concept that came to be known as "Super Saturday": the women's and men's finals were played on the final Saturday and Sunday of the tournament respectively, and their respective semifinals were held one day prior. The women's final was originally held in between the two men's semifinal matches; in 2001, the women's final was moved to the evening so it could be played on primetime television, citing a major growth in popularity for women's tennis among viewers.[28] This scheduling pattern helped to encourage television viewership, but proved divisive among players because it only gave them less than a day's rest between their semifinals and championship match.[29][30]

For five consecutive tournaments between 2008 through 2012, the men's final was postponed to Monday due to weather. In 2013 and 2014, the USTA intentionally scheduled the men's final on a Monday—a move praised for allowing the men's players an extra day's rest following the semifinals, but drew the ire of the ATP for further deviating from the structure of the other Grand Slams.[31][29] In 2015, the Super Saturday concept was dropped, and the US Open returned to a format similar to the other Grand Slams, with women's and men's finals on Saturday and Sunday. However, weather delays forced both sets of semifinals to be held on Friday that year.[32][30]

In 2018, the tournament was the first Grand Slam tournament that introduced the shot clock to keep a check on the time consumed by players between points.[lower-alpha 4] The reason for this change was to increase the pace of play.[34] The clock is placed in a position visible to players, the chair umpire and fans.[35] Since 2020, all Grand Slams, ATP, and WTA tournaments apply this technology.[36]

In 2020, the event was held without spectators due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[37] An announcement that the wheelchair tennis competition would not be held caused controversy because USTA did not consult with the disabled athletes prior to it, as it had consulted with the players' organizations for the non-disabled competitions. After accusations of discrimination, USTA was forced to backtrack, admitting that it should have discussed the decision with the disabled competitors and offering them either $150,000 to be split between them (compared with $3.3m to be split between the players affected by the cancellation of each of the men's and women's qualifying competition and reductions in the mixed-doubles pool), a competition as part of the Open with 95% of the 2019 prize fund, or a competition to be held at the USTA base in Florida.[38]

Grounds

.jpg.webp)

The grounds of the US Open have 22 outdoor courts (plus 12 practice courts just outside the East Gate) consisting of four "show courts" (Arthur Ashe Stadium, Louis Armstrong Stadium, the Grandstand, and Court 17), 13 field courts, and 5 practice courts.

The main court is the 23,771-seat[39] Arthur Ashe Stadium, which opened in 1997. A US$180 million[40] retractable roof was added in 2016.[41] The stadium is named after Arthur Ashe, who won the men's singles title at the inaugural US Open in 1968, the Australian Open in 1970, and Wimbledon in 1975 and who was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame in 1985. The next largest court is the 14,061-seat Louis Armstrong Stadium, which cost US$200 million to build and opened in 2018.[40] The 6,400-seat lower tier of this stadium is separately ticketed, reserved seating while the 7,661-seat upper tier is general admission and not separately ticketed.[40][42] The third largest court is the 8,125-seat Grandstand in the southwest corner of the grounds, which opened in 2016.[41] Court 17 in the southeast corner of the grounds is the fourth largest stadium. It opened with temporary seating in 2011 and received its permanent seating the following year.[43] It has a seating capacity of 2,800, all of which is general admission and not separately ticketed.[43] It is nicknamed "The Pit", partly because the playing surface is sunk 8 feet into the ground.[43][44] The total seating capacity for practice courts P1-P5 is 672 and for competition Courts 4–16 is 12,656, itemized as follows:[45]

- Courts 11 & 12: 1,704 each

- Court 7: 1,494

- Court 5: 1,148

- Courts 10 & 13: 1,104 each

- Court 4: 1,066

- Court 6: 1,032

- Court 9: 624

- Courts 14 & 15: 502 each

- Courts 8 & 16: 336 each

All the courts used by the US Open are illuminated, allowing matches and television coverage to extend into primetime. In 2001, the women's singles final was intentionally scheduled for primetime for the first time. CBS Sports president Sean McManus cited significant public interest in star players Serena Williams and Venus Williams and the good ratings performance of the 1999 women's singles final, which was pushed into primetime by rain delays.[28]

Surface

From 1978 to 2019, the US Open was played on a hardcourt surface called Pro DecoTurf. It is a multi-layer cushioned surface and classified by the International Tennis Federation as medium-fast.[46] Each August before the start of the tournament, the courts are resurfaced.[47] In March 2020, the USTA announced that Laykold would become the new court surface supplier beginning with the 2020 tournament.[48]

Since 2005, all US Open and US Open Series tennis courts have been painted a shade of blue (trademarked as "US Open Blue") inside the lines to make it easier for players, spectators, and television viewers to see the ball.[49] The area outside the lines is still painted "US Open Green".[49]

Player line call challenges

In 2006, the US Open introduced instant replay reviews of line calls, using the Hawk-Eye computer system. It was the first Grand Slam tournament to use the system.[50] The Open felt the need to implement the system because of the controversial quarterfinal match at the 2004 US Open between Serena Williams and Jennifer Capriati, where important line calls went against Williams.[51] Instant replay was available only on the Arthur Ashe Stadium and Louis Armstrong Stadium courts through the 2008 tournament. In 2009, it became available on the Grandstand court. Starting in 2018, all competition courts are outfitted with Hawk-Eye and all matches in the main draws (Men's and Women's Singles and Doubles) follow the same procedure – each player is allowed three incorrect challenges per set, with one more being allowed in a tiebreak. Player challenges were eliminated in 2021, when the tournament became the second Grand Slam to fully incorporate Hawk-Eye Live, where all line calls are made electronically; the previous year's tournament had also incorporated Hawk-Eye Live on all courts except for Arthur Ashe and Louis Armstrong stadiums to reduce personnel during the COVID-19 pandemic.[52]

In 2007, JPMorgan Chase renewed its sponsorship of the US Open and, as part of the arrangement, the replay system was renamed to "Chase Review" on in-stadium video and television.[53]

Point and prize money distribution

Ranking points for the men (ATP) and women (WTA) have varied at the US Open through the years. Below is a series of tables for each of the competitions showing the ranking points on offer for each event:

Senior

| Event | W | F | SF | QF | R4 | R3 | R2 | R1 | Q | Q3 | Q2 | Q1 |

| Men's singles | 2000 | 1200 | 720 | 360 | 180 | 90 | 45 | 10 | 25 | 16 | 8 | 0 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men's doubles | 0 | — | — | — | — | — | ||||||

| Women's singles | 1300 | 780 | 430 | 240 | 130 | 70 | 10 | 40 | 30 | 20 | 2 | |

| Women's doubles | 10 | — | — | — | — | — |

Wheelchair

|

Junior

|

Prize money

The total prize money for the 2022 US Open was $60,102,000 and is the largest package of all Grand Slams and the largest in tournament history. The package is divided as follows:[54]

| Event[55] | W | F | SF | QF | Round of 16 | Round of 32 | Round of 64 | Round of 128 | Q3 | Q2 | Q1 |

| Singles | $2,600,000 | $1,300,000 | $705,000 | $445,000 | $278,000 | $188,000 | $121,000 | $80,000 | $44,000 | $33,600 | $21,100 |

| Doubles | $688,000 | $344,000 | $172,000 | $97,500 | $56,400 | $35,800 | $21,300 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Mixed doubles | $163,000 | $81,500 | $42,000 | $23,200 | $14,200 | $8,300 | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

The men's and women's singles prize money (US$42,628,000) accounts for 70.9 percent of total player base compensation, while men's and women's doubles (US$6,943,200), men's and women's singles qualifying (US$6,259,200), and mixed doubles (US$667,700) account for 11.6 percent, 10.4 percent, and 1.1 percent, respectively. All prize money for the doubles competitions are distributed per team. The prize money for the wheelchair draw amounts to a total of US$1,032,000, which accounts for a total of 1.7 percent of the package, and additional expenses, such as per diem and direct hotel payments of US$2,571,900 accounts for a total of 4.3 percent.[54]

In 2012, the USTA agreed to increase the US Open prize money to $50,400,000 by 2017. As a result, the prize money for the 2013 tournament was US$33.6 million, a record US$8.1 million increase from 2012. The champions of the 2013 US Open Series also had the opportunity to add US$2.6 million in bonus prize money, potentially bringing the total 2013 US Open purse to more than US$36 million.[56] In 2014, the prize money was US$38.3 million.[57] In 2015, the prize money was raised to US$42.3 million.[58] In 2021, the USTA set a new record for the highest prize money and total player compensation in the tournament's history with $57,462,000, and also boosted the prize money for the qualifying tournament to $6,000,000, a 66% increase over the package in 2019.[59]

Champions

Former champions

- Men's singles

- Women's singles

- Men's doubles

- Women's doubles

- Mixed doubles

- All champions

Current champions

|

Most recent finals

| 2022 Event | Champion | Runner-up | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men's singles | 6–4, 2–6, 7–6(7–1), 6–3 | ||

| Women's singles | 6–2, 7–6(7–5) | ||

| Men's doubles | 7–6(7–4), 7–5 | ||

| Women's doubles | 3–6, 7–5, 6–1 | ||

| Mixed doubles | 4–6, 6–4, [10–7] |

Records

_(cropped).jpg.webp)

| Record | Era | Player(s) | Count | Years |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men since 1881 | ||||

| Most singles titles | Pre-Open Era | 7 | 1881–87 | |

| 1901–02, 1907–11 | ||||

| 1920–25, 1929 | ||||

| Open Era | 5 | 1974, 1976, 1978, 1982–83 | ||

| 1990, 1993, 1995–96, 2002 | ||||

| 2004–08 | ||||

| Most consecutive singles titles | Pre-Open Era | 7 | 1881–87 | |

| Open Era | 5 | 2004–08 | ||

| Most doubles titles | Pre-Open Era | 6 | 1882–84, 1886–87 with James Dwight 1885 with Joseph Clark | |

| 1899–1901 with Dwight F. Davis 1904–06 with Beals Wright | ||||

| Open Era | 6 | 2005, 2008, 2010, 2012, 2014 with Bob Bryan 2018 with Jack Sock | ||

| Most consecutive doubles titles | Pre-Open Era | 6 | 1882–87 | |

| Open Era | 2 | 1995–96 | ||

| 1995–96 | ||||

| 2021–22 | ||||

| 2021–22 | ||||

| Most mixed doubles titles | Pre-Open Era | 4 | 1894–96 with Juliette Atkinson 1898 with Carrie Neely | |

| 1907 with May Sayers 1909, 1911, 1915 with Hazel Hotchkiss Wightman | ||||

| 1913–14 with Mary Browne 1922–23 with Molla Mallory | ||||

| 1943–46 with Margaret Osborne duPont | ||||

| Open Era | 1966 with Donna Floyd 1967, 1971, 1973 with Billie Jean King | |||

| 1969–70, 1972 with Margaret Court 1980 with Wendy Turnbull | ||||

| 2003 with Katarina Srebotnik 2004 with Vera Zvonareva 2006 with Martina Navratilova 2010 with Liezel Huber | ||||

| Most Championships (singles, doubles & mixed doubles) |

Pre-Open Era | 16 | 1913–29 (7 singles, 5 doubles, 4 mixed doubles) | |

| Open Era | 9 | 2003–14 (5 doubles, 4 mixed doubles) | ||

| Women since 1887 | ||||

| Most singles titles | Pre-Open Era | 8 | 1915–18, 1920–22, 1926 | |

| Open Era | 6 | 1975–78, 1980, 1982 | ||

| 1999, 2002, 2008, 2012–14 | ||||

| Most consecutive singles titles | Pre-Open Era | 4 | 1915–18 | |

| 1932–35 | ||||

| Open Era | 4 | 1975–78 | ||

| Most doubles titles | Pre-Open Era | 13 | 1941 with Sarah Palfrey Cooke 1942–50, 1955–57 with Louise Brough | |

| Open Era | 9 | 1977 with Betty Stöve 1978, 1980 with Billie Jean King 1983–84, 1986–87 with Pam Shriver 1989 with Hana Mandlíková 1990 with Gigi Fernández | ||

| Most consecutive doubles titles | Pre-Open Era | 10 | 1941 with Sarah Palfrey Cooke 1942–50 with Louise Brough | |

| Open Era | 3 | 2002–04 | ||

| 2002–04 | ||||

| Most mixed doubles titles | Pre-Open Era | 9 | 1943–46 with Bill Talbert 1950 with Ken McGregor 1956 with Ken Rosewall 1958–60 with Neale Fraser | |

| Open Era | 3 | 1969–70, 1972 with Marty Riessen | ||

| 1971, 1973 with Owen Davidson 1976 with Phil Dent | ||||

| 1985 with Heinz Günthardt 1987 with Emilio Sánchez 2006 with Bob Bryan | ||||

| Most Championships (singles, doubles & mixed doubles) |

Pre-Open Era | 25 | 1941–60 (3 singles, 13 doubles, 9 mixed doubles) | |

| Open Era | 16 | 1977–2006 (4 singles, 9 doubles, 3 mixed doubles) | ||

| Miscellaneous | ||||

| Unseeded champions | Men | 1994 | ||

| Women | 2009 2017 2021 (the only qualifier to win a major title) | |||

| Youngest singles champion | Men | 19 years and 1 month (1990)[60] | ||

| Women | 16 years and 8 months (1979)[60] | |||

| Oldest singles champion | Men | 38 years and 8 months (1911)[60] | ||

| Women | 42 years and 5 months (1926)[60] | |||

Media and attendance

Media coverage

The US Open's website allows viewing of live streaming video, but unlike other Grand Slam tournaments, does not allow watching video on demand. The site also offers live radio coverage.

United States

ESPN took full control of televising the event in 2015. When taking over, ESPN ended 47 years of coverage produced and aired by CBS.[61] ESPN uses ESPN and ESPN2 for broadcasts, while putting outer court coverage on ESPN+.[62] The tournament briefly returned to broadcast television for only a few seconds in 2022, as ABC aired a quad box with a simulcast look in of ESPN2’s coverage multiple times during ABC’s college football coverage.

Other regions

- Continental Europe – Eurosport

- Latin America & Caribbean – ESPN International

- Middle East & North Africa – beIN Sports

- Southern Africa – SuperSport

- Indian Subcontinent – Sony Pictures Sports Network

- Southeast Asia (except Vietnam) – SPOTV

- Oceania – ESPN International

Exceptions

- UK and Ireland – Prime Video (2022), Sky Sports (from 2023)[63]

- Australia – Nine Network and Stan Sport

- Canada – TSN and RDS

- China – CCTV and iQIYI

- Japan – Wowow

- Pakistan – PTV Sports[64]

- South Korea – JTBC

- Vietnam – Disney+ Hotstar

Source[65]

Recent attendance

- 2022: 776,120

- 2021: 631,134[66]

- 2020: 0[lower-alpha 5]

- 2019: 737,872

- 2018: 732,663

- 2017: 691,143

- 2016: 688,542

- 2015: 691,280

- 2014: 713,642

- 2013: 713,026

- 2012: 710,803

- 2011: 658,664

- 2010: 712,976

- 2009: 721,059

- 2008: 720,227

- 2007: 715,587

- 2006: 640,000

- 2005: 659,538

Sources: US Open,[67] Record Attendance 2019,[68] City University of New York (CUNY)[69][70]

See also

- List of US Open singles finalists during the Open Era, records and statistics

Notes

- DecoTurf was used from 1978 to 2019, and Laykold since 2020.

- Except Arthur Ashe Stadium and Louis Armstrong Stadium during rain delays.

- In the main draws, there are 128 singles players (S) and 64 doubles teams (D), and there are 128 and 16 entrants in the respective qualifying (Q) draws.

- Once the chair umpire has announced the score following the previous point, the countdown starts and players have 25 seconds to begin their service motion. However, the chair umpire has the ability and discretion to pause or reset the clock to 25 seconds the clock if a point with a particularly long rally merits a pause for the players to recover their breath. In normal circumstances during the game, if the player has not started the service motion at the completion of the 25-second countdown, the chair umpire issues a time violation. The server will receive a warning and for each subsequent violation, the player loses a first serve (second serves are supposed to happen without delay, so the clock won't be used). In the case of the receiver, if it isn't ready at the end of 25 seconds, the chair umpire first issues a warning, then the loss of a point with every other violation. After even-numbered games, the chair umpire will start the clock when the balls are all in place on the server's end of the court.[33]

- The 2020 US Open was played behind closed doors due to the COVID-19 pandemic in New York.

References

- "2022 US Open Prize Money". USOpen.org. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- "Tiebreak in Tennis". Tennis Companion. October 29, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- "National Lawn-Tennis Tournament" (PDF). The New York Times. July 14, 1881. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- Bud Collins (2010). The Bud Collins History of Tennis (2nd ed.). New York City: New Chapter Press. pp. 10, 452, 454. ISBN 978-0942257700.

- "USTA LOCATIONS". www.usta.com. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- Bill Shannon (1981). United States Tennis Association Official Encyclopedia of Tennis (Centennial ed.). New York City: Harper & Row. pp. 237–249. ISBN 0-06-014896-9.

- "How the U.S. Open found its home in New York at Flushing Meadows". Sports Illustrated. June 24, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "Championship tennis tournament". The Chicago Tribune. May 28, 1893. p. 7.

- "On courts of turf". The Chicago Tribune. July 24, 1893. p. 12.

- "Tennis notes" (PDF). The New York Times. July 24, 1893.

- "Tennis Tournament at Newport Again" (PDF). The New York Times. February 4, 1911. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- "Newport May Lose Tennis Tourney" (PDF). The New York Times. January 17, 1915. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- "Want Newport for Tennis Tourney" (PDF). The New York Times. January 18, 1915. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- "A Tennis "Solar Plexus"" (PDF). The New York Times. January 23, 1915. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- "Tourney Goes to New York". Boston Evening Transcript. February 6, 1915. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- "'All-Comers' Tourney to be Restricted" (PDF). The New York Times. February 7, 1915. Retrieved July 16, 2012.

- "Newport Loses Tennis Tourney" (PDF). The New York Times. February 6, 1915. Retrieved July 21, 2012.

- "SITES OF THE U.S. CHAMPIONSHIPS" (PDF). www.usta.com. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- "Germantown Cricket Club History". Germantown Cricket Club. Archived from the original on April 3, 2012. Retrieved December 15, 2013.

- Robertson, Max (1974). The Encyclopedia of Tennis. The Viking Press. p. 33. ISBN 067029408X.

- "Recommendation is made for the abolition of blind draw in promotion of tennis tourneys". Newspapers.com. Evening Public Ledger. December 19, 1921. p. 21.

- E. Digby Baltzell (2013). Sporting Gentlemen: Men's Tennis from the Age of Honor to the Cult of the Superstar. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers. p. 182. ISBN 978-14128-5180-0.

- "New England youths spring net upset". Minneapolis Morning Tribune. August 22, 1960. p. 18 – via Newspapers.com.

Paul Sullivan and Ned Weld, two youngsters from New England, toppled Antonio Palafox and Joaquin Reyes of Mexico, 6 up, 8-6, 3-6, 1-6, 6-3 Sunday in the only opening day upset of the national doubles tennis championships at Longwood Cricket club.

- "U.S. Open History". Tennis.com. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- Maverick, Vickey (August 27, 2016). "When the US Open was played on clay…". Medium. Retrieved May 15, 2020.

- "Grand Slams – US Open". International Tennis Federation. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- Richard Sandomir (August 3, 2006). "Tennis Center to Be Named for Billie Jean King". The New York Times.

- "Ladies first – women's open final is so hot, they're moving it to prime-time". New York Post. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- "ATP blasts US Open over Monday final". ESPN.co.uk. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- "Traditional US Open scheduling favors Federer". ESPN.go.com. August 31, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- "US Open schedules Monday finish". ESPN.co.uk. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- "U.S. Open schedule: How to watch semifinal matches". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- "US Open '18: On the clock! 25-second countdown's Slam debut". AP. August 26, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- Marshall, Ashley (July 11, 2018). "Shot clock, warm-up clock to be implemented at 2018 US Open". usopen.org. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "USTA, ATP & WTA Implement Rules Innovations At Events Throughout Summer". atptour.com. July 11, 2018. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "Tennis: ATP to use Shot Clock in all tournaments in 2020". Reuters. London. March 13, 2019. Retrieved March 29, 2020.

- "US Open to be held behind closed doors after New York governor gives go-ahead". BBC Sport. June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "After complaints, USTA gives options for US Open wheelchair tournament". Tennis.com. June 19, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.

- "USTA ARTHUR ASHE STADIUM". Rossetti. August 15, 2016. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- Cindy Shmerler (August 20, 2018). "What's New, and What's Free, at the 2018 U.S. Open". The New York Times. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- David W. Dunlap (August 29, 2016). "How the Roof Was Raised at Arthur Ashe Stadium". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- Tim Newcomb (August 8, 2018). "Finishing Touches at U.S. Open's Home". VenuesNow. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- Howard Beck (September 4, 2011). "A Tiny New Stage for High-Energy Tennis". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- Robson, Douglas. "New show court draws a crowd, quietly" USA Today (August 29, 2011)

- "USTA Tennis Championships Magazine: 2018 US Open Edition". United States Tennis Association. p. 26. Retrieved August 28, 2018.

- "About Court Pace Classification". International Tennis Federation. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- Thomas Lin (September 7, 2011). "Speed Bumps on a Hardcourt". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- "US Open Changing Hard-Court Brand for First Time since 1970S". tennis.com. Associated Press. March 23, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Tim Newcomb (August 24, 2015). "The science behind creating the U.S. Open courts and signature colors". Sports Illustrated.

- Williams, Daniel (January 11, 2007). "Australian Open Preview". TIME. Time Warner. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

As seen at last year's U.S. Open and numerous events since, this is the best innovation in tennis since yellow balls.

- Chris Broussard (September 9, 2004). "Williams Receives Apology, and Umpire's Open Is Over". The New York Times.

- Agency (September 6, 2021). "US Open 2021: 'Hawk-Eye Live' replaces line judge as technology takes over US Open; officials reduced from 400 to 130". InsideSport. Retrieved September 8, 2021.

- "Chase signs mega renewal with Open". Retrieved September 9, 2016.

- "2022 US Open Prize Money". United States Tennis Association. Retrieved August 29, 2022.

- US Open Prize Money 2022

- "US Open makes long-term commitment to the game". United States Tennis Association. Retrieved June 25, 2013.

- "2014 US Open Prize Money" Archived August 26, 2015, at the Wayback Machine US Open

- "US prize money upped" Archived July 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine DPA International, July 14, 2014.

- "2021 US Open offers record prize money, $57.5 million in total player compensation". US Open. August 23, 2021. Retrieved September 11, 2021.

- "Youngest and oldest champions". United States Tennis Association. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

- "ESPN to Gain Full Rights to U.S. Open in 2015". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2018.

- "International TV Schedule". United States Tennis Association. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- insider.co.uk (April 1, 2022). "Sky Sports taking back U.S. Open rights in U.K." Sports Business Journal. Retrieved April 19, 2022.

- "The Final Grand Slam of 2021 LIVE on PTV Sports". Twitter.com. August 30, 2021. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- International TV Schedule Retrieved 2021-09-16.

- "2021 US Open Finals, By the Numbers". usopen.org. September 12, 2021.

- "US Open History – Year-by-Year". United States Tennis Association (USTA).

- "2019 US Open, by the numbers". US Open. September 8, 2019.

- "U.S. Open Tennis – Total Attendance (By Year)". www.baruch.cuny.edu. City University of New York.

- September 12; 2017. "U.S. Open Attendance Up From '16; USTA Earns Roughly $125M In Ticket Revenue". www.sportsbusinessdaily.com.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

Media related to US Open (tennis) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to US Open (tennis) at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

_(52036462443)_(edited).jpg.webp)

_(48199020336).jpg.webp)

_(52144533385).jpg.webp)

_(52144292229).jpg.webp)

_(41168839590).jpg.webp)

_(48199057067).jpg.webp)

_(52191140653).jpg.webp)

_(48521737101).jpg.webp)