Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (UK: /ˌvæskoʊ də ˈɡɑːmə/, US: /ˌvɑːskoʊ də ˈɡæmə/;[1][2] European Portuguese: [ˈvaʃku ðɐ ˈɣɐ̃mɐ]; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.[3]

Count of Vidigueira Vasco da Gama | |

|---|---|

| |

| Viceroy of Portuguese India | |

| In office 5 September 1524 – 24 December 1524 | |

| Monarch | John III of Portugal |

| Preceded by | Duarte de Menezes |

| Succeeded by | Henrique de Menezes |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1460 or 1469 Sines, Alentejo, Kingdom of Portugal |

| Died | 24 December 1524 (aged approximately 55–65) Cochin, Kingdom of Cochin |

| Resting place | Jerónimos Monastery, Lisbon, Portugal |

| Spouse | Catarina de Ataíde |

| Children | Francisco da Gama, 2nd Count of Vidigueira Estêvão da Gama, Governor of India Cristóvão da Gama, Captain of Malacca Among others |

| Parents |

|

| Occupation | Explorer, Viceroy of India |

| Signature |  |

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope[4] (1497–1499) was the first to link Europe and Asia by an ocean route, connecting the Atlantic and the Indian oceans. This is widely considered a milestone in world history, as it marked the beginning of a sea-based phase of global multiculturalism.[5] Da Gama's discovery of the sea route to India opened the way for an age of global imperialism and enabled the Portuguese to establish a long-lasting colonial empire along the way from Africa to Asia. The violence and hostage-taking employed by da Gama and those who followed also assigned a brutal reputation to the Portuguese among India's indigenous kingdoms that would set the pattern for western colonialism in the Age of Exploration.[6] Traveling the ocean route allowed the Portuguese to avoid sailing across the highly disputed Mediterranean and traversing the dangerous Arabian Peninsula. The sum of the distances covered in the outward and return voyages made this expedition the longest ocean voyage ever made until then.[7]

After decades of sailors trying to reach the Indies, with thousands of lives and dozens of vessels lost in shipwrecks and attacks, da Gama landed in Calicut on 20 May 1498. Unopposed access to the Indian spice routes boosted the economy of the Portuguese Empire, which was previously based along northern and coastal West Africa. The main spices at first obtained from Southeast Asia were pepper and cinnamon, but soon included other products, all new to Europe. Portugal maintained a commercial monopoly of these commodities for several decades. It was not until a century later that other European powers, first the Dutch Republic and England, later France and Denmark, were able to challenge Portugal's monopoly and naval supremacy in the Cape Route.

Da Gama led two of the Portuguese India Armadas, the first and the fourth. The latter was the largest and departed for India four years after his return from the first one. For his contributions, in 1524 da Gama was appointed Governor of India, with the title of Viceroy, and was ennobled as Count of Vidigueira in 1519. He remains a leading figure in the history of exploration, and homages worldwide have celebrated his explorations and accomplishments. The Portuguese national epic poem, Os Lusíadas, was written in his honour by Luís de Camões.

Early life

Vasco da Gama was born in 1460 in the town of Sines,[3] one of the few seaports on the Alentejo coast, southwest Portugal, probably in a house near the church of Nossa Senhora das Salas.

Vasco da Gama's father was Estêvão da Gama, who had served in the 1460s as a knight of the household of Infante Ferdinand, Duke of Viseu.[8] He rose in the ranks of the military Order of Santiago. Estêvão da Gama was appointed alcaide-mór (civil governor) of Sines in the 1460s, a post he held until 1478; after that he continued as a receiver of taxes and holder of the Order's commendas in the region.

Estêvão da Gama married Isabel Sodré, a daughter of João Sodré (also known as João de Resende), scion of a well-connected family of English origin.[9] Her father and her brothers, Vicente Sodré and Brás Sodré, had links to the household of Infante Diogo, Duke of Viseu, and were prominent figures in the military Order of Christ. Vasco da Gama was the third of five sons of Estêvão da Gama and Isabel Sodré – in (probable) order of age: Paulo da Gama, João Sodré, Vasco da Gama, Pedro da Gama and Aires da Gama. Vasco also had one known sister, Teresa da Gama (who married Lopo Mendes de Vasconcelos).[10]

Little is known of da Gama's early life. The Portuguese historian Teixeira de Aragão suggests that he studied at the inland town of Évora, which is where he may have learned mathematics and navigation. It has been claimed that he studied under Abraham Zacuto, an astrologer and astronomer, but da Gama's biographer Subrahmanyam thinks this dubious.[11]

Around 1480, da Gama followed his father (rather than the Sodrés) and joined the Order of Santiago.[12] The master of Santiago was Prince John, who ascended to the throne in 1481 as King John II of Portugal. John II doted on the Order, and the da Gamas' prospects rose accordingly.

In 1492, John II dispatched da Gama on a mission to the port of Setúbal and to the Algarve to seize French ships in retaliation for peacetime depredations against Portuguese shipping – a task that da Gama rapidly and effectively performed.[13]

Exploration before da Gama

From the earlier part of the 15th century, Portuguese expeditions organized by Prince Henry the Navigator had been reaching down the African coastline, principally in search of west African riches (notably, gold and slaves).[14] They had greatly extended Portuguese maritime knowledge, but had little profit to show for the effort. After Henry's death in 1460, the Portuguese Crown showed little interest in continuing this effort and, in 1469, licensed the neglected African enterprise to a private Lisbon merchant consortium led by Fernão Gomes. Within a few years, Gomes' captains expanded Portuguese knowledge across the Gulf of Guinea, doing business in gold dust, melegueta pepper, ivory and sub-Saharan slaves. When Gomes' charter came up for renewal in 1474, Prince John (future John II), asked his father Afonso V of Portugal to pass the African charter to him.[15]

Upon becoming king in 1481, John II of Portugal set out on many long reforms. To break the monarch's dependence on the feudal nobility, John II needed to build up the royal treasury; he considered royal commerce to be the key to achieving that. Under John II's watch, the gold and slave trade in west Africa was greatly expanded. He was eager to break into the highly profitable spice trade between Europe and Asia, which was conducted chiefly by land. At the time, this was virtually monopolized by the Republic of Venice, who operated overland routes via Levantine and Egyptian ports, through the Red Sea across to the spice markets of India. John II set a new objective for his captains: to find a sea route to Asia by sailing around the African continent.[16]

By the time Vasco da Gama was in his 20s, the king's plans were coming to fruition. In 1487, John II dispatched two spies, Pero da Covilhã and Afonso de Paiva, overland via Egypt to East Africa and India, to scout the details of the spice markets and trade routes. The breakthrough came soon after, when John II's captain Bartolomeu Dias returned from rounding the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, having explored as far as the Fish River (Rio do Infante) in modern-day South Africa and having verified that the unknown coast stretched away to the northeast.[16]

An explorer was needed who could prove the link between the findings of Dias and those of da Covilhã and de Paiva, and connect these separate segments into a potentially lucrative trade route across the Indian Ocean.

First voyage

On 8 July 1497 Vasco da Gama led a fleet of four ships[17] with a crew of 170 men from Lisbon. The distance traveled in the journey around Africa to India and back was greater than the length of the equator.[17][18] The navigators included Portugal's most experienced, Pero de Alenquer, Pedro Escobar, João de Coimbra, and Afonso Gonçalves. It is not known for certain how many people were in each ship's crew but approximately 55 returned, and two ships were lost. Two of the vessels were carracks, newly built for the voyage; the others were a caravel and a supply boat.[17]

The four ships were:

- São Gabriel, commanded by Vasco da Gama; a carrack of 178 tons, length 27 m, width 8.5 m, draft 2.3 m, sails of 372 m2

- São Rafael, commanded by his brother Paulo da Gama; similar dimensions to the São Gabriel

- Berrio (nickname, officially called São Miguel), a caravel, slightly smaller than the former two, commanded by Nicolau Coelho

- A storage ship of unknown name, commanded by Gonçalo Nunes, destined to be scuttled in Mossel Bay (São Brás) in South Africa[8]

Journey to the Cape

The expedition set sail from Lisbon on 8 July 1497. It followed the route pioneered by earlier explorers along the coast of Africa via Tenerife and the Cape Verde Islands. After reaching the coast of present-day Sierra Leone, da Gama took a course south into the open ocean, crossing the Equator and seeking the South Atlantic westerlies that Bartolomeu Dias had discovered in 1487.[19] This course proved successful and on 4 November 1497, the expedition made landfall on the African coast. For over three months the ships had sailed more than 10,000 kilometres (6,000 mi) of open ocean, by far the longest journey out of sight of land made by that time.[17][20]

By 16 December, the fleet had passed the Great Fish River (Eastern Cape, South Africa) – where Dias had anchored – and sailed into waters previously unknown to Europeans. With Christmas pending, da Gama and his crew gave the coast they were passing the name Natal, which carried the connotation of "birth of Christ" in Portuguese.

Mozambique

Vasco da Gama spent 2 to 29 March 1498 in the vicinity of Mozambique Island. Arab-controlled territory on the East African coast was an integral part of the network of trade in the Indian Ocean. Fearing the local population would be hostile to Christians, da Gama impersonated a Muslim and gained audience with the Sultan of Mozambique. With the paltry trade goods he had to offer, the explorer was unable to provide a suitable gift to the ruler. Soon the local populace became suspicious of da Gama and his men. Forced by a hostile crowd to flee Mozambique, da Gama departed the harbor, firing his cannons into the city in retaliation.[21]

Mombasa

In the vicinity of modern Kenya, the expedition resorted to piracy, looting Arab merchant ships that were generally unarmed trading vessels without heavy cannons. The Portuguese became the first known Europeans to visit the port of Mombasa from 7 to 13 April 1498, but were met with hostility and soon departed.

Malindi

Vasco da Gama continued north, arriving on 14 April 1498 at the friendlier port of Malindi, whose leaders were having a conflict with those of Mombasa. There the expedition first noted evidence of Indian traders. Da Gama and his crew contracted the services of a pilot who used his knowledge of the monsoon winds to guide the expedition the rest of the way to Calicut, located on the southwest coast of India. Sources differ over the identity of the pilot, calling him variously a Christian, a Muslim, and a Gujarati. One traditional story describes the pilot as the famous Arab navigator Ibn Majid, but other contemporaneous accounts place Majid elsewhere, and he could not have been near the vicinity at the time.[22] None of the Portuguese historians of the time mentions Ibn Majid. Vasco da Gama left Malindi for India on 24 April 1498.

Calicut, India

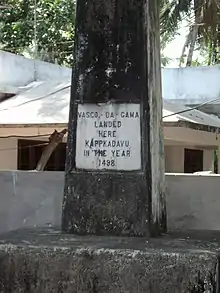

The fleet arrived in Kappadu near Kozhikode (Calicut), in Malabar Coast (present day Kerala state of India), on 20 May 1498. The King of Calicut, the Samudiri (Zamorin), who was at that time staying in his second capital at Ponnani, returned to Calicut on hearing the news of the foreign fleet's arrival. The navigator was received with traditional hospitality, including a grand procession of at least 3,000 armed Nairs, but an interview with the Zamorin failed to produce any concrete results. When local authorities asked da Gama's fleet, "What brought you hither?", they replied that they had come "in search of Christians and spices."[23] The presents that da Gama sent to the Zamorin as gifts from Dom Manuel – four cloaks of scarlet cloth, six hats, four branches of corals, twelve almasares, a box with seven brass vessels, a chest of sugar, two barrels of oil and a cask of honey – were trivial, and failed to impress. While Zamorin's officials wondered at why there was no gold or silver, the Muslim merchants who considered da Gama their rival suggested that the latter was only an ordinary pirate and not a royal ambassador.[24] Vasco da Gama's request for permission to leave a factor behind him in charge of the merchandise he could not sell was turned down by the King, who insisted that da Gama pay customs duty – preferably in gold – like any other trader, which strained the relation between the two. Annoyed by this, da Gama carried a few Nairs and sixteen fishermen (mukkuva) off with him by force.[25]

Return

Vasco da Gama left Calicut on 29 August 1498. Eager to set sail for home, he ignored the local knowledge of monsoon wind patterns that were still blowing onshore. The fleet initially inched north along the Indian coast, and then anchored in at Anjediva island for a spell. They finally struck out for their Indian Ocean crossing on 3 October 1498. But with the winter monsoon yet to set in, it was a harrowing journey. On the outgoing journey, sailing with the summer monsoon wind, da Gama's fleet crossed the Indian Ocean in only 23 days; now, on the return trip, sailing against the wind, it took 132 days.

Da Gama saw land again only on 2 January 1499, passing before the coastal Somali city of Mogadishu, then under the influence of the Ajuran Empire in the Horn of Africa. The fleet did not make a stop, but passing before Mogadishu, the anonymous diarist of the expedition noted that it was a large city with houses of four or five storeys high and big palaces in its center and many mosques with cylindrical minarets.[26]

Da Gama's fleet finally arrived in Malindi on 7 January 1499, in a terrible state – approximately half of the crew had died during the crossing, and many of the rest were afflicted with scurvy. Not having enough crewmen left standing to manage three ships, da Gama ordered the São Rafael scuttled off the East African coast, and the crew re-distributed to the remaining two ships, the São Gabriel and the Berrio. Thereafter, the sailing was smoother. By early March, they had arrived in Mossel Bay, and crossed the Cape of Good Hope in the opposite direction on 20 March, reaching the west African coast by 25 April.

The diary record of the expedition ends abruptly here. Reconstructing from other sources, it seems they continued to Cape Verde, where Nicolau Coelho's Berrio separated from Vasco da Gama's São Gabriel and sailed on by itself.[27] The Berrio arrived in Lisbon on 10 July 1499 and Nicolau Coelho personally delivered the news to King Manuel I and the royal court, then assembled in Sintra. In the meantime, back in Cape Verde, da Gama's brother, Paulo da Gama, had fallen grievously ill. Da Gama elected to stay by his side on Santiago island and handed the São Gabriel over to his clerk, João de Sá, to take home. The São Gabriel under Sá arrived in Lisbon sometime in late July or early August. Da Gama and his sickly brother eventually hitched a ride with a Guinea caravel returning to Portugal, but Paulo da Gama died en route. Da Gama disembarked at the Azores to bury his brother at the monastery of São Francisco in Angra do Heroismo, and lingered there for a little while in mourning. He eventually took passage on an Azorean caravel and finally arrived in Lisbon on 29 August 1499 (according to Barros),[28] or early September[17] (8th or 18th, according to other sources). Despite his melancholic mood, da Gama was given a hero's welcome and showered with honors, including a triumphal procession and public festivities. King Manuel wrote two letters in which he described da Gama's first voyage, in July and August 1499, soon after the return of the ships. Girolamo Sernigi also wrote three letters describing da Gama's first voyage soon after the return of the expedition.

The expedition had exacted a large cost – two ships and over half the men had been lost. It had also failed in its principal mission of securing a commercial treaty with Calicut. Nonetheless, the small quantities of spices and other trade goods brought back on the remaining two ships demonstrated the potential of great profit for future trade.[29] Vasco da Gama was justly celebrated for opening a direct sea route to Asia. His path would be followed up thereafter by yearly Portuguese India Armadas.

The spice trade would prove to be a major asset to the Portuguese royal treasury, and other consequences soon followed. For example, da Gama's voyage had made it clear that the east coast of Africa, the Contra Costa, was essential to Portuguese interests; its ports provided fresh water, provisions, timber, and harbors for repairs, and served as a refuge where ships could wait out unfavorable weather. One significant result was the colonization of Mozambique by the Portuguese Crown.

Rewards

In December 1499, King Manuel I of Portugal rewarded Vasco da Gama with the town of Sines as a hereditary fief (the town his father, Estêvão, had once held as a commenda). This turned out to be a complicated affair, for Sines still belonged to the Order of Santiago. The master of the Order, Jorge de Lencastre, might have endorsed the reward – after all, da Gama was a Santiago knight, one of their own, and a close associate of Lencastre himself. But the fact that Sines was awarded by the king provoked Lencastre to refuse out of principle, lest it encourage the king to make other donations of the Order's properties.[30] Da Gama would spend the next few years attempting to take hold of Sines, an effort that would estrange him from Lencastre and eventually prompt da Gama to abandon his beloved Order of Santiago, switching over to the rival Order of Christ in 1507.

In the meantime, da Gama made do with a substantial hereditary royal pension of 300,000 reis. He was awarded the noble title of Dom (lord) in perpetuity for himself, his siblings and their descendants. On 30 January 1502, da Gama was awarded the title of Almirante dos mares de Arabia, Persia, India e de todo o Oriente ("Admiral of the Seas of Arabia, Persia, India and all the Orient") – an overwrought title reminiscent of the ornate Castilian title borne by Christopher Columbus (evidently, Manuel must have reckoned that if Castile had an 'Admiral of the Ocean Seas', then surely Portugal should have one too).[31] Another royal letter, dated October 1501, gave da Gama the personal right to intervene and exercise a determining role on any future India-bound fleet.

Around 1501, Vasco da Gama married Catarina de Ataíde, daughter of Álvaro de Ataíde, the alcaide-mór of Alvor (Algarve), and a prominent nobleman connected by kinship with the powerful Almeida family (Catarina was a first cousin of Dom Francisco de Almeida).[32]

Second voyage

The follow-up expedition, the Second India Armada, launched in 1500 under the command of Pedro Álvares Cabral with the mission of making a treaty with the Zamorin of Calicut and setting up a Portuguese factory in the city. However, Pedro Cabral entered into a conflict with the local Arab merchant guilds, with the result that the Portuguese factory was overrun in a riot and up to 70 Portuguese were killed. Cabral blamed the Zamorin for the incident and bombarded the city. Thus war broke out between Portugal and Calicut.

Vasco da Gama invoked his royal letter to take command of the 4th India Armada, scheduled to set out in 1502, with the explicit aim of taking revenge upon the Zamorin and force him to submit to Portuguese terms. The heavily armed fleet of fifteen ships and eight hundred men left Lisbon on 12 February 1502. It was followed in April by another squadron of five ships led by his cousin, Estêvão da Gama (the son of Aires da Gama), which caught up to them in the Indian Ocean. The 4th Armada was a veritable da Gama family affair. Two of his maternal uncles, Vicente Sodré and Brás Sodré, were pre-designated to command an Indian Ocean naval patrol, while brothers-in-law Álvaro de Ataíde (brother of Vasco's wife Catarina) and Lopo Mendes de Vasconcelos (betrothed to Teresa da Gama, Vasco's sister) captained ships in the main fleet.

On the outgoing voyage, da Gama's fleet opened contact with the East African gold trading port of Sofala and reduced the sultanate of Kilwa to tribute, extracting a substantial sum of gold.

Pilgrim ship incident

On reaching India in October 1502, da Gama's fleet intercepted Mirim,[33] a ship of Muslim pilgrims at Madayi travelling from Calicut to Mecca. Described in detail by eyewitness Thomé Lopes and chronicler Gaspar Correia, da Gama looted the ship with over 400 pilgrims on board including 50 women, locked in the passengers, the owner and an ambassador from Egypt and burned them to death. They offered their wealth, which "could ransom all the Christian slaves in the Kingdom of Fez and much more" but were not spared. Da Gama looked on through the porthole and saw the women bringing up their gold and jewels and holding up their babies to beg for mercy.[34] The lives of twenty children were spared against a forced conversion to Christianity[33]

Calicut

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

After stopping at Cannanore, Gama drove his fleet before Calicut, demanding redress for the treatment of Cabral. Having known of the fate of the pilgrims' ship, the Zamorin adopted a conciliatory attitude towards the Portuguese and expressed willingness to sign a new treaty but da Gama made a call to the Hindu king to expel all Muslims from Calicut before beginning negotiations, which was turned down.[35] At the same time however, the Zamorin sent a message to his rebellious vassal, the Raja of Cochin urging cooperation and obedience to counter the Portuguese threat; the ruler of Cochin forwarded this message to Gama, which reinforced his opinion of the Indians as duplicitous.[36] After demanding the expulsion of Muslims from Calicut to the Hindu Zamorin, the latter sent the high priest Talappana Namboothiri (the very same person who conducted da Gama to the Zamorin's chamber during his much celebrated first visit to Calicut in May 1498) for talks. Da Gama called him a spy, ordered the priest's lips and ears to be cut off and after sewing a pair of dog's ears to his head, sent him away.[37] The Portuguese fleet then bombarded the unfortified city for nearly two days from the sea, severely damaging it. He also captured several rice vessels and cut off the crew's hands, ears and noses, dispatching them with a note to the Zamorin, in which Gama declared that he would be open to friendly relations once the Zamorin had paid for the items plundered from the feitoria as well as the gunpowder and cannonballs.[38][39]

Seabattle

The violent treatment meted out by da Gama quickly brought trade along the Malabar Coast of India, upon which Calicut depended, to a standstill. The Zamorin ventured to dispatch a fleet of strong warships to challenge da Gama's armada, but which Gama managed to defeat in a naval battle before Calicut harbor.

Cochin

Da Gama loaded up with spices at Cochin and Cannanore, small nearby kingdoms at war with the Zamorin, whose alliances had been secured by prior Portuguese fleets. The 4th armada left India in early 1503. Da Gama left behind a small squadron of caravels under the command of his uncle, Vicente Sodré, to patrol the Indian coast, to continue harassing Calicut shipping, and to protect the Portuguese factories at Cochin and Cannanore from the Zamorin's inevitable reprisals.

Vasco da Gama arrived back in Portugal in September 1503, effectively having failed in his mission to bring the Zamorin to submission. This failure, and the subsequent more galling failure of his uncle Vicente Sodré to protect the Portuguese factory in Cochin, probably counted against any further rewards. When the Portuguese king Manuel I of Portugal decided to appoint the first governor and viceroy of Portuguese India in 1505, da Gama was conspicuously overlooked, and the post given to Francisco de Almeida.

Interlude

For the next two decades, Vasco da Gama lived out a quiet life, unwelcome in the royal court and sidelined from Indian affairs. His attempts to return to the favor of Manuel I (including switching over to the Order of Christ in 1507), yielded little. Almeida, the larger-than-life Afonso de Albuquerque and, later on, Albergaria and Sequeira, were the king's preferred point men for India.

After Ferdinand Magellan defected to the Crown of Castile in 1518, Vasco da Gama threatened to do the same, prompting the king to undertake steps to retain him in Portugal and avoid the embarrassment of losing his own "Admiral of the Indies" to Spain.[40] In 1519, after years of ignoring his petitions, King Manuel I finally hurried to give Vasco da Gama a feudal title, appointing him the first Count of Vidigueira, a count title created by a royal decree issued in Évora on 29 December, after a complicated agreement with Dom Jaime, Duke of Braganza, who ceded him on payment the towns of Vidigueira and Vila dos Frades. The decree granted Vasco da Gama and his heirs all the revenues and privileges related,[41] thus establishing da Gama as the first Portuguese count who was not born with royal blood.[42]

Third voyage and death

.jpg.webp)

After the death of King Manuel I in late 1521, his son and successor, King John III of Portugal set about reviewing the Portuguese government overseas. Turning away from the old Albuquerque clique (now represented by Diogo Lopes de Sequeira), John III looked for a fresh start. Vasco da Gama re-emerged from his political wilderness as an important adviser to the new king's appointments and strategy. Seeing the new Spanish threat to the Maluku Islands as the priority, Vasco da Gama advised against the obsession with Arabia that had pervaded much of the Manueline period, and continued to be the dominant concern of Duarte de Menezes, then-governor of Portuguese India. Menezes also turned out to be incompetent and corrupt, subject to numerous complaints. As a result, John III decided to appoint Vasco da Gama himself to replace Menezes, confident that the magic of his name and memory of his deeds might better impress his authority on Portuguese India, and manage the transition to a new government and new strategy.

By his appointment letter of February 1524, John III granted Vasco da Gama the privileged title of "Viceroy", being only the second Portuguese governor to enjoy that title (the first was Francisco de Almeida in 1505).[43] His second son, Estêvão da Gama was simultaneously appointed Capitão-mor do Mar da Índia ('Captain-major of the Indian Sea', commander of the Indian Ocean naval patrol fleet), to replace Duarte's brother, Luís de Menezes. As a final condition, Gama secured from John III of Portugal the commitment to appoint all his sons successively as Portuguese captains of Malacca.

Setting out in April 1524, with a fleet of fourteen ships, Vasco da Gama took as his flagship the famous large carrack Santa Catarina do Monte Sinai on her last journey to India, along with two of his sons, Estêvão and Paulo. After a troubled journey (four or five of the ships were lost en route), he arrived in India in September. Vasco da Gama immediately invoked his high viceregent powers to impose a new order in Portuguese India, replacing all the old officials with his own appointments. But Gama contracted malaria not long after arriving, and died in the city of Cochin on Christmas Eve in 1524, three months after his arrival. As per royal instructions, da Gama was succeeded as governor of India by one of the captains who had come with him, Henrique de Menezes (no relation to Duarte). Da Gama's sons Estêvão and Paulo immediately lost their posts and joined the returning fleet of early 1525 (along with the dismissed Duarte de Menezes and Luís de Menezes).[44]

Vasco da Gama's body was first buried at St. Francis Church, at Fort Kochi in the city of Kochi, but his remains were returned to Portugal in 1539. The body of Vasco da Gama was re-interred in Vidigueira in a casket decorated with gold and jewels.

.jpg.webp)

The Monastery of the Hieronymites, in Belém, which would become the necropolis of the Portuguese royal dynasty of Aviz, was erected in the early 1500s near the launch point of Vasco da Gama's first journey, and its construction funded by a tax on the profits of the yearly Portuguese India Armadas. In 1880, da Gama's remains and those of the poet Luís de Camões (who celebrated da Gama's first voyage in his 1572 epic poem, The Lusiad), were moved to new carved tombs in the nave of the monastery's church, only a few meters away from the tombs of the kings Manuel I and John III, whom da Gama had served.

Marriage and descendants

Vasco da Gama and his wife, Catarina de Ataíde, had six sons and one daughter:[45]

- Dom Francisco da Gama, who inherited his father's titles as 2nd Count of Vidigueira and the 2nd "Admiral of the Seas of India, Arabia and Persia". He remained in Portugal.

- Dom Estevão da Gama, after his abortive 1524 term as Indian patrol captain, he was appointed for a three-year term as captain of Malacca, serving from 1534 to 1539 (includes the last two years of his younger brother Paulo's term). He was subsequently appointed as the 11th governor of India from 1540 to 1542.

- Dom Paulo da Gama (having the same name as his uncle Paulo), captain of Malacca from 1533 to 1534, killed in a naval action off Malacca.

- Dom Cristovão da Gama, captain of Malacca from 1538 to 1540; nominated to succeed in Malacca, but executed by Ahmad ibn Ibrahim during the Ethiopian-Adal war in 1542.

- Dom Pedro da Silva da Gama, appointed captain of Malacca from 1548 to 1552.

- Dom Álvaro de Ataíde da Gama, appointed captain of Malacca fleet in the 1540s, captain of Malacca itself from 1552 to 1554.

- Dona Isabel de Ataíde da Gama, only daughter, married Dom Ignacio de Noronha, son of the first Count of Linhares.

His male-line issue became extinct in 1735, when the 7th Count of Vidigueira, Dom Vasco Baltasar José Luís Gama died, leaving only one daughter from his marriage, Dona Maria José da Gama, who inherited the Vidigueira estate. The title thus continued through this female-line.[46]

Intergenerations

- Dom Vasco da Gama, 3rd Count of Vidigueira, the nobility and military personnel, son of Francisco (2nd Count) and grandson of Vasco da Gama.

- Dom Francisco da Gama, 4th Count of Vidigueira, the viceroy (1597–1600) and governor (1622–1628) of India, son of Vasco (3rd Count) and great-grandson of Vasco da Gama.

Legacy

Vasco da Gama is one of the most famous and celebrated explorers from the Age of Discovery. As much as anyone after Henry the Navigator, he was responsible for Portugal's success as an early colonising power. Beside the fact of the first voyage itself, it was his astute mix of politics and war on the other side of the world that placed Portugal in a prominent position in Indian Ocean trade. Following da Gama's initial voyage, the Portuguese crown realized that securing outposts on the eastern coast of Africa would prove vital to maintaining national trade routes to the Far East.

However, his fame is tempered by such incidents and attitudes as displayed in the notorious Pilgrim Ship Incident previously discussed.

The Portuguese national epic, the Lusíadas of Luís Vaz de Camões, largely concerns Vasco da Gama's voyages.[47]

The 1865 grand opera L'Africaine: Opéra en Cinq Actes, composed by Giacomo Meyerbeer from a libretto by Eugène Scribe, prominently includes the character of Vasco da Gama. The events depicted, however, are fictitious. Meyerbeer's working title for the opera was Vasco da Gama. A 1989 production of the opera by the San Francisco Opera featured noted tenor Plácido Domingo in the role of da Gama.[48] The 19th-century composer Louis-Albert Bourgault-Ducoudray composed an eponymous 1872 opera based on da Gama's life and exploits at sea.

The port city of Vasco da Gama in Goa is named after him, as is the crater Vasco da Gama on the Moon. There are three football clubs in Brazil (including Club de Regatas Vasco da Gama) and Vasco Sports Club in Goa that were also named after him. There exists a church in Kochi, Kerala called Vasco da Gama Church, and a private residence on the island of Saint Helena. The suburb of Vasco in Cape Town also honours him.

.jpg.webp)

A few places in Lisbon's Parque das Nações are named after the explorer, such as the Vasco da Gama Bridge, Vasco da Gama Tower and the Centro Comercial Vasco da Gama shopping centre.[49] The Oceanário in the Parque das Nações has a mascot of a cartoon diver with the name of "Vasco", who is named after the explorer.[50]

Vasco da Gama was the only explorer on the final pool of Os Grandes Portugueses. Although the final shortlist featured other Age of Discovery related people, they were not actually explorers nor navigators for any matter.

The Portuguese Navy has a class of frigates named after him. There are three Vasco da Gama class frigates in total, of which the first one also bears his name.

The Portuguese government erected two navigational beacons, Dias Cross and da Gama Cross, to commemorate da Gama and Bartolomeu Dias who were the first modern European explorers to reach the Cape of Good Hope. When lined up, these crosses point to Whittle Rock, a large, permanently submerged shipping hazard in False Bay.

South African musician Hugh Masekela recorded an anti-colonialist song entitled "Colonial Man", which contains the lyrics "Vasco da Gama was no friend of mine", and another song entitled "Vasco da Gama (The Sailor Man)". Both songs were included in his 1976 album Colonial Man.

Vasco da Gama appears as an antagonist in the Indian film Urumi. The film, directed by Santosh Sivan, depicts atrocities and progression to establish the Portuguese empire by da Gama in India.

In March 2016, archaeologists working off the coast of Oman identified a shipwreck believed to be that of the Esmeralda from da Gama's 1502–1503 fleet. The wreck was initially discovered in 1998. Later underwater excavations took place between 2013 and 2015 through a partnership between the Oman Ministry of Heritage and Culture and Blue Water Recoveries Ltd., a shipwreck recovery company. The vessel was identified through such artifacts as a "Portuguese coin minted for trade with India (one of only two coins of this type known to exist) and stone cannonballs engraved with what appear to be the initials of Vincente Sodré, da Gama's maternal uncle and the commander of the Esmeralda."[51]

See also

- Chronology of European exploration of Asia

References

Citations

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15255-6.

- "Vasco da Gama | Biography, Achievements, Route, Map, Significance, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- "Vasco da Gama | Biography, Achievements, Route, Map, Significance, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

- Nigel, Cliff (2011). Holy War: How Vasco da Gama's Epic Voyages Turned the Tide in a Centuries-Old Clash of Civilizations. Harper..

- M. G. S. Narayanan, Calicut: The City of Truth (2006) Calicut University Publications.

- Diffie, Bailey W. and George D. Winius, Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580, p. 176

- Ames, Glenn J. (2008). The Globe Encompassed. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-13-193388-0..

- The Sodrés were said to have been descended from Frederick Sudley, of Gloucestershire, who accompanied the Earl of Cambridge to Portugal in 1381, and subsequently settled there (Subrahmanyam, 1997, p. 61).

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, p. 61.

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, p. 62.

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, pp. 60–61.

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, p. 63.

- de Oliveira Marques, António Henrique R. (1972). History of Portugal. Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-03159-9, pp. 158–160, 362–370.

- Parry, 1981, pp. 132-135

- Scammell, 1981, p. 232

- Diffie, Bailey W.; Winius, George D. (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1850. Europe and the World in the Age of Expansion. Vol. 1. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-0-8166-0850-8.

- Da Gama's Round Africa to India, fordham.edu Retrieved 16 November 2006.

- Gago Coutinho, C.V. (1951–52) A Nautica dos Descobrimentos: os descobrimentos maritimos visitos por um navegador, Lisbon: Agencia Geral do Ultramar; pp. 319–363; Axelson, E. (1988) "The Dias Voyage, 1487–1488: toponymy and padrões", Revista da Universidade de Coimbra, Vol. 34, pp. 29–55 offprint; Waters, D.W. (1988) "Reflections Upon Some Navigational and Hydrographic Problems of the XVth Century Related to the voyage of Bartolomeu Dias", Revista da Universidade de Coimbra, Vol. 34, pp. 275–347. offprint.

- Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 177–178. ISBN 978-0-393-06259-5.

- "Vasco da Gamma Seeks Sea Route to India" Archived 22 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Old News Publishing, Retrieved 8 July 2006.

- Fernandez-Armesto, Felipe (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 178–179. ISBN 978-0-393-06259-5.

- Ames, Glenn J. (2005). Vasco da Gama: Renaissance Crusader. New York: Pearson/Longman. p. 50.

- Castaneda, Herman Lopes de, The First Book of the Historie of the Discoveries and Conquests of the East India by the Portingals, London, 1582, in Kerr, Robert (ed.) A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels Vol. II, London, 1811.

- M.G.S. Narayanan, Calicut: The City of Truth (2006) Calicut University Publications (The incident is mentioned by Camoes in The Lusiads, wherein it is stated that the Zamorin "showed no signs of treachery" and that "on the other hand, da Gama's conduct in carrying off the five men he had entrapped on board his ships is indefensible.").

- Da Gama's First Voyage p. 88.

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, p. 149.

- João de Barros, Da Asia, Dec. I, Lib. IV, c. 11, p. 370.

- Diffie & Winius, 1977, p. 185.

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, p. 168.

- João de Barros (1552, pp. 23–24) dates this appointment in January 1502, just before da Gama's departure on his second voyage. But Subrahmanyan (1997, p. 169), following Braancamp Freire, conjectures this award may have been made as early as January 1500.

- Catarina de Ataíde's mother, Maria da Silva, was the sister of Beatriz da Silva, mother of Francisco de Almeida. The Almeidas provided a substantial part of Catarina's dowry (Subrahmanyan, 1997, p. 174).

- Allen, Charles (2017). Coromandel : a personal history of South India. London: Little, Brown. p. 233. ISBN 9781408705391.

- Nambiar O.K, The Kunjalis – Admirals of Calicut, Bombay, 1963.

- "Vasco da Gama Arrives in India 1498". Archived from the original on 18 January 2004. Retrieved 29 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Dana Thompson, Felicity Ruiz, Michelle Mejiak; 15 December 1998. Retrieved 8 July 2006. - Prof. Roger Crowley: Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire, Faber & Faber, 2015, p.131.

- M. G. S. Narayanan, Calicut: The City of Truth (2006) Calicut University Publications.

- Sreedhara Menon. A. A Survey of Kerala History (1967), p. 152. D. C. Books Kottayam.

- Roger Crowley, in Conquerors: How Portugal Forged the First Global Empire, Faber & Faber, 2015, p.134.

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, p. 278.

- Vasco Da Gama, Ernest George Ravenstein, "A journal of the first voyage of Vasco da Gama, 1497–1499", p. Hakluyt Society, Issue 99 of Works issued by the Hakluyt Society, ISBN 81-206-1136-5.

- At this time in Portugal, there were only twelve counts, one count-bishop, two marquises and two dukes (Subrahmaynam, 1997, p. 281).

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, p. 304.

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, pp. 343–345.

- See also Diogo do Couto (Decadas de Asia, Dec. IV, Lib. 8, c. 2); Teixeira de Aragão pp. 15–16, and Castanhoso (1898: p. viiff.).

- Freire, Anselmo Braamcamp (1921). Brasões da Sala de Sintra, Livro Segundo. Robarts - University of Toronto. Coimbra : Imprensa da Universidade. p. 93.

- "The Lusiads". World Digital Library. 1800–1882. Retrieved 31 August 2013..

- Subrahmanyam, 1997, p. 2.

- "Centro Vasco da Gama". Centrovascodagama.pt. Retrieved 29 January 2009..

- "Vasco participa na maior Parada das Mascotes em Portugal". Lisbon Oceanarium. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- Romey, Kristin (14 March 2016). "Shipwreck Discovered from Explorer Vasco da Gama's Fleet". National Geographic. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

Bibliography

- Ames, Glenn J. (2004). Vasco da Gama: Renaissance Crusader. Longman. ISBN 978-0-321-09282-3.

- Ames, Glenn J. (2007). The Globe Encompassed: The Age of European Discovery, 1500–1700. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-193388-0.

- Castanhoso, M. de (1898) Dos feitos de D. Christovam da Gama em Ethiopia Lisbon: Imprensa nacional. online

- Corrêa, Gaspar (2001). The Three Voyages of Vasco da Gama, and His Viceroyalty. Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4021-9543-3. Facsimile reprint of an 1869 edition by the Hakluyt Society, London.

- Diffie, Bailey W.; Winius, George D. (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire 1415-1580. University of Minnesota Press.

- Disney, Anthony; Booth, Emily (2000). The Indian Ocean in World History. New Delhi and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2001). Civilizations. Basingstoke and Oxford: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7432-0248-0.

- Fernández-Armesto, Felipe (2006). Pathfinders: A Global History of Exploration. W.W. Norton. pp. 177–181. ISBN 978-0-393-06259-5.

- Jayne, Kingsley Garland (1910). Vasco Da Gama and His Successors 1460 to 1580. London: Meuthen & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-0-548-00895-9.

- Panikkar, K.M. (1959). Asia and Western Dominance: A Survey of the Vasco da Gama Epoch of Asian History, 1498–1945 (new ed.). London: Allen & Unwin. ASIN B000Q5T6X6.

- Parry, J. H. (1981). Age of Reconnaissance. University of California Press.

- Ravenstein, E. G.; ed. and trans. (1898). A Journal of the First Voyage of Vasco da Gama, 1497–1499. London: Hakluyt Society. Retrieved 4 March 2019 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01296-6) - Russell-Wood, A.J.R. (1993). A World on the Move: The Portuguese in Africa, Asia, and America, 1415–1808. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-09427-0.

- Scammell, G. V. (1981). The World Encompassed. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520044227.

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay (1997). The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47072-8.

- Teixeira de Aragão, A.C. (1887) Vasco da Gama e a Vidigueira: um estudo historico. Lisbon: Sociedade de Geografia de Lisboa online

- Towle, George Makepeace (c. 1878). Vasco da Gama, his voyages and adventures. Boston: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard.

Further reading

| Library resources about Vasco da Gama |

- Vasco da Gama (Ernst Georg Ravenstein, Gaspar Corrêa, Alvaro Velho) [2011] Viartis ISBN 978-1-906421-04-5

- Vasco da Gama: Renaissance Crusader (Glen J.Ames) [2004] Longman ISBN 0-321-09282-1

- The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama (Sanjay Subrahmanyam) [1997] Cambridge University Press ISBN 978-0-521-47072-8

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 11 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 433–434.

.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)