White-nose syndrome

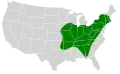

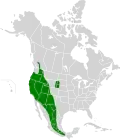

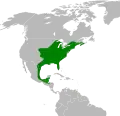

White-nose syndrome (WNS) is a fungal disease in North American bats which has resulted in the dramatic decrease of the bat population in the United States and Canada, reportedly killing millions as of 2018.[1] The condition is named for a distinctive fungal growth around the muzzles and on the wings of hibernating bats. It was first identified from a February 2006 photo taken in a cave located in Schoharie County, New York.[2] The syndrome has rapidly spread since then. In early 2018, it was identified in 33 U.S. states and seven Canadian provinces; plus the fungus, albeit sans syndrome, had been found in three additional states.[3] Most cases are in the eastern half of both countries, but in March 2016, it was confirmed in a little brown bat in Washington state.[4] In 2019, evidence of the fungus was detected in California for the first time, although no affected bats were found.[5]

.jpg.webp)

The disease is caused by the fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, which colonizes the bat's skin. No obvious treatment or means of preventing transmission is known,[6][7] and some species have declined >90% within five years of the disease reaching a site.[8]

The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has called for a moratorium on caving activities in affected areas[9] and strongly recommends to decontaminate clothing or equipment in such areas after each use. The National Speleological Society maintains an up-to-date page to keep cavers apprised of current events and advisories.[10]

Impact

As of 2012 white-nose syndrome was estimated to have caused 5.7 million to 6.7 million bat deaths in North America.[1] In 2008 bats declined in some caves by more than 90%.[11][12] Alan Hicks with the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation described the impact in 2008 as "unprecedented" and "the gravest threat to bats...ever seen."[13] In 2016, it was reported that bat populations in the caves and mines of Georgia had been decimated in a similar fashion, after the fungus was first detected in there in 2013.[14]

As of 2021, twelve North American bat species, including two endangered species and one threatened species have been affected by WNS or exposed to the causative fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, with impacts varying widely.[15] As of 2012 four species have suffered substantial declines and extinction of at least one species was predicted.[8] Declines included species already listed as endangered in the US, such as the Indiana bat, whose hibernacula, in many states, have been affected.[16] The once-common little brown bat has suffered a major population collapse in the northeastern US,[17] although some individuals may be genetically resilient to the disease.[18] In 2012 the northern long-eared myotis (Myotis septentrionalis) was reported to be extirpated from all sites where the disease has been present for more than four years.[8] In 2009, the Virginia big-eared bat (Corynorhinus townsendii virginianus), the official state bat of Virginia,[19] and the gray bat had yet to suffer measurable declines.

Beyond the direct effect on bat populations, WNS has broader ecological implications. The Forest Service estimated in 2008 that the die-off from white-nose syndrome means that at least 2.4 million pounds (1.1 million kg or 1100 tons) of insects will go uneaten and become a financial burden to farmers, possibly leading to crop damage or having other economic impact in New England.[11] It is estimated that bats save farmers in the U.S. 3 billion dollars annually in pest control services. In addition, numerous bat species provide crucial pollination and seed dispersal services.[4]

In 2008, comparisons were raised to colony collapse disorder, another incompletely understood phenomenon resulting in the abrupt disappearance of Western honey bee colonies,[20][21] and with chytridiomycosis, a fungal skin disease linked with worldwide declines in amphibian populations.[22][23]

| Confirmed North American bat species identified with diagnostic symptoms of white-nose syndrome:[24] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Scientific name | Common Name | Range | Conservation Status[25] |

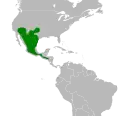

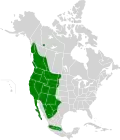

.jpg.webp) | Eptesicus fuscus | Big brown bat |  | Least Concern |

_(9403869552)_(cropped).jpg.webp) | Myotis evotis | Long-eared myotis |  | Least Concern |

| Myotis grisescens | Gray bat |  | Vulnerable |

.jpg.webp) | Myotis leibii | Eastern small-footed bat |  | Endangered |

.jpg.webp) | Myotis lucifugus | Little brown bat |  | Endangered |

.jpg.webp) | Myotis septentrionalis | Northern myotis |  | Near threatened |

| Myotis sodalis | Indiana bat |  | Near threatened |

| Myotis thysanodes | Fringed myotis |  | Least Concern |

| Myotis velifer | Cave myotis |  | Least Concern |

| Myotis volans | Long-legged myotis |  | Least Concern |

_(11362476624).jpg.webp) | Myotis yumanensis | Yuma bat |  | Least Concern |

| Perimyotis subflavus | Tricolored bat |  | Vulnerable |

Research

Biologists of the US Fish and Wildlife Service have been collecting information at each site in regard to the number of bats affected, the geographic extent of the outbreaks and samples of affected bats. They developed a geographic database to track the location of sites, where WNS has been found.[26] The Fish and Wildlife Service has been partnering with the Northeastern Cave Conservancy to track movements of cavers that have visited affected sites in New York.[26]

In 2009, the Service advised closing caves to explorers in 20 states, from the Midwest to New England. This directive was supposed to be extended to 13 southern states. One Virginia scientist stated, "If it gets into caves more to our south, in places like Tennessee, Kentucky, Georgia and Alabama, we’re going to be talking deaths in the millions."[19] In March 2012, WNS was discovered on some tri-colored bats (Perimyotis subflavus) in Russell Cave in Jackson County, Alabama.[27]

Cause

The fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans is the primary cause of WNS.[28] It preferably grows in the 4–15 °C range (39–59 °F) and will not grow at temperatures above 20 °C (68 °F).[29] It is cold loving or psychrophilic. It is phylogenetically related to Geomyces spp., but with a conidial morphology distinct from characterized members of this genus.[22] Early laboratory research placed the fungus in the genus Geomyces,[22][30] but later phylogenic evaluation revealed this organism should be reclassified within Pseudogymnoascus.[31]

A 2011 study found that 100% of healthy North American bats infected with the fungus cultured from infected bats exhibit lesions consistent with the disease.[30] Direct microscopy and culture analyses demonstrated that the skin of the WNS-affected bats is colonized by the fungus.[22]

The species has been found on bats in Europe and Asia,[32][33][34] however, no unusual mortality could be assigned to the infections.[35][36] Genetic studies have shown that the fungus must have been in Europe for a long time and was most likely transported to North America as a novel pathogen.[37][38]

Infection

A laboratory experiment suggests that physical contact is required for one bat to infect another, because bats in mesh cages adjacent to infected bats did not contract the fungus. This implies that the fungus is not airborne, or at least, is not transmitted from bat to bat through the air.[30] The primary way this fungus is spread is through bat-to-bat contact or infected cave-to-bat contact. The role of humans in the spread of the disease is debated. It is likely the fungus was brought to North America by human activities, because no bats normally migrate between Europe and North America, and the fungus was first discovered in New York where there are major trans-Atlantic air and shipping terminals. Geographical translocation of bats by ship and airplane have been documented.[39] Research has shown the fungus can persist on human clothing and thus could be carried between locations by people, but as of 2016 it has not been demonstrated that this has played any role in the spread of the disease.[40][41]

Signs of disease

The visually most obvious indication of infection is the presence of white fungal growth on the muzzles and wing membranes of affected bats. However, P. destructans may also be present in lower concentrations without leading to obvious visible cues, persisting as a cryptic infection; this appears to be more likely in some species than in others (e.g., the gray bat).[42]

As early as 2011 it was hypothesized that prematurely expending the fat reserves for winter survival may be a cause for death.[43] A 2014 study found that while bats can successfully fight off the fungus between mid-October and May, their resistance falls to near zero once they begin to hibernate when the animals shut their metabolism down to save energy. The signs observed with WNS include unusual winter behavior like abnormally frequent or abnormally long arousal from the state of torpor. Each time they rouse, they start using more energy and if this happens too much, they can use up their fat stores and starve. Some bats will even leave their winter shelters in search of absent insects and risk dying of exposure in the cold. Consequently many infected bats don’t make it until spring when their immune systems and body temperatures ramp up and insect food sources again emerge.[44]

Pathophysiology

Until December 2014 the cause for the abnormal behavior was unclear, as no physiological data linking altered behavior to hypothesized increased energy demands existed.

The Fish and Wildlife Service published a case control study in December 2014: Of 60 little brown bats, 39 bats were randomly assigned to infection by applying conidia to skin of the dorsal surface of both wings and 21 bats remained controls. All were observed for 95 days and euthanized. 32 bats developed WNS (30 mild to moderate and 2 moderate to severe). The remaining seven infected bats were PCR-positive with normal wing histology. Infected bats with WNS had higher proportions of lean tissue mass to fat tissue mass than uninfected bats in measuring an increase in total body water volume as a percent of body mass. Infected bats used twice as much energy as healthy bats, and starved to death. Direct calculations of energy expenditure failed for most bats, because isotope concentrations were indistinguishable from background. There was also no difference in torpor durations in this experiment; the average torpor duration for infected bats was 9.1 days with an average arousal of 54 min. Average torpor duration for control bats was 8.5 days with an average arousal duration of 55 min.[45] Infected bats suffered respiratory acidosis with an almost 40% higher mean pCO₂ than healthy bats, and potassium concentration was significantly higher.[45] Hence the following model of infection exists: Pseudogymnoascus destructans colonizes and eventually invades the wing epidermis. This causes increased energy expenditure, and an elevated blood pCO₂ and bicarbonate called chronic respiratory acidosis, possibly due to diffusion problems. Hyperkalemia (elevated blood potassium) ensues because of an acidosis-induced extracellular shift of potassium. Dying, infected cells could also leak their (intracellular) potassium into the blood. The damaged wing epidermis might stimulate increased frequencies of arousal from torpor, which removes excess CO₂ and normalizes blood pH, at the expense of hydration and fat reserves. With worsening wing damage, the effects are exacerbated by water and electrolyte loss across the wound (hypotonic dehydration), which stimulates more frequent arousals in a positive feedback loop that ultimately leads to death.[45]

Geographical spread

The disease was first reported in January 2007 in New York caves,[20] although it was retrospectively detected in a photograph taken in early 2006. It spread to other New York caves and into Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut by 2008.[46][47] In early 2009, it was confirmed in New Hampshire,[48] New Jersey, Pennsylvania,[49] Virginia,[50] West Virginia[46] and in March 2010, in Ontario Canada, Maryland,[51] Middle Tennessee, Missouri,[52] and Quebec, Canada.[53][54] In 2011, the syndrome was confirmed in Ohio,[55] Indiana,[56] Kentucky,[57] North Carolina,[50] Maine,[58] New Brunswick and Nova Scotia.[59] In the winter of 2011–2012, Alabama,[27] Delaware[60] and Arkansas[61] confirmed the disease in bats and new cases showed up in northeastern Ohio,[62] and Acadia National Park in Maine.[63] Confirmed cases appeared in 2013 in Georgia,[64] South Carolina,[65] Illinois,[66] and the Canadian province of Prince Edward Island.[67] In March, 2014, WDNR and USGS staff conducting routine surveillance detected white-nose syndrome in a single mine in Grant County Wisconsin and the USGS National Wildlife Health Center later confirmed the disease.[68] In April, 2014, the Michigan Department of Natural Resources announced that the disease had been found in Alpena County, Mackinac County, and Dickinson County.[69] In May, 2014, after retesting, the Myotis velifer specimen from Oklahoma and other swabs and samples from the area tested negative, and Oklahoma and Myotis velifer were removed from the list of WNS suspects.[70]

As of April 2014, the syndrome had been confirmed in 25 states and 5 Canadian provinces. The causative fungus has been confirmed in three additional states: Iowa, Minnesota, and Mississippi.[71]

A little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus) was found in Washington state infected with white-nose syndrome in March 2016. Researchers suspect through DNA analysis that the source of infection in this individual originated in the Eastern U.S. This has been the westernmost case discovered in North America thus far.[72] A second case of white-nose syndrome was detected in Washington in April 2017. The infected bat was a Yuma myotis (Myotis yumanensis), which was the first time the disease has been found in this species.[73]

In March 2017, the fungus was found on bats in six north Texas counties, bringing the number of states with the fungus to 33. Three bat species tested positive.[74]

In April 2018, it was announced that bats in Kansas were documented with white-nose syndrome, making it the first time infected bats were found in Kansas.[75]

In May 2018, it was announced that bats in Manitoba were found to be infected with white-nose syndrome.[76]

In May 2019, the fungus was found in the home of the largest colony of bats in the world, Bracken Cave, near San Antonio, Texas. [77]

While field surveys conducted in 2020 have confirmed the presence of the fungus throughout multiple counties in Montana, the first death of an infected bat was confirmed in April 2021.[78]

Decontamination

The fungus Pseudogymnoascus destructans, or a closely related species of fungus, has been found in soil samples from infected caves and suggests that it can be transported from cave to cave by soil, such as that carried by human clothing.[79] Precautionary decontamination methods are being encouraged to inhibit the possible spread of spores by humans. The WNS Decontamination Team, a sub-group of the Disease Management Working Group, published a national decontamination protocol on March 15, 2012. They revised the protocol on June 25, 2012.[80] In May 2015, based upon laboratory tests, a recommendation was issued to increase the temperature of the hot water treatment for submersible gear to 60 °C (140 °F) for 20 minutes (up from 50 °C (122 °F)). All other guidance in the existing protocol should be followed.[81]

As of 2008, cave management and preservation organizations had begun requesting that cave visitors limit their activities and disinfect clothing and equipment that has been used in possibly infected caves.[82] The current protocol goes further, and indicates that in many cases it is inappropriate to reuse even disinfected gear, and that new gear should be used.[80]: see p.3 flow chart

In some cases, access to caves is being closed entirely.[83] According to New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Commissioner Basil Seggos, "Research ... demonstrates that white-nose syndrome makes bats highly susceptible to disturbances. Even a single, seemingly quiet visit can kill bats that would otherwise survive the winter. If you see hibernating bats, assume you are doing harm and leave immediately." When hibernating bats are disturbed, it raises their body temperatures, depleting fat reserves.[84]

Treatments

A 2019 study found that bats treated with Pseudomonas fluorescens, a probiotic bacterium previously used in chytridiomycosis treatments, were five times more likely to survive post-hibernation.[85]

See also

- Anthropocene

- Chytridiomycosis

- Decline in amphibian populations

- Holocene extinction

References

- "NUSGS report on white-nose syndrome". US Geological Survey. May 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-09-30. Retrieved 2018-07-07.

- Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Behr M, Meteyer CU, Berlowski-Zier BM, Buckles EL, Coleman JT, Darling SR, Gargas A, Niver R, Okoniewski JC, Rudd RJ, Stone WB (January 2009). "Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen?" (PDF). Science. 323 (5911): 227. doi:10.1126/science.1163874. PMID 18974316. S2CID 23869393.

- Whitenosesyndrome.org: "Where is WNS now" July 2018

- "White Nose Syndrome of Bats Fact Sheet | Washington Department of Fish & Wildlife". wdfw.wa.gov. Retrieved 2016-02-03.

- DanaMichaels2013 (2019-07-05). "Deadly Bat Fungus Detected in California". CDFW News. Retrieved 2019-07-22.

- Coghlan A (26 October 2011). "Bat killer identified". New Scientist.

- Ferrante J. "Bucknell University professor, national research team identify cause of White-Nose Syndrome in bats". Archived from the original on 2019-01-03. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- Langwig KE, Frick WF, Bried JT, Hicks AC, Kunz TH, Kilpatrick AM (September 2012). "Sociality, density-dependence and microclimates determine the persistence of populations suffering from a novel fungal disease, white-nose syndrome". Ecology Letters. 15 (9): 1050–7. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01829.x. PMID 22747672. S2CID 12803482.

- "Cave activity discouraged to help protect bats from deadly white-nose syndrome" (PDF) (Advisory). US Fish and Wildlife Service. March 26, 2009.

- "White Nose Syndrome Page". National Speleological Society. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- Daley B (2008-02-07). "Die-off of bats could hurt area crops". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- Kelley T (2008-03-25). "Bats Perish, and No One Knows Why". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- Shapley D (2008-02-05). "The Gravest Threat to Bats Ever Seen". The Daily Green. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- "Fungal disease sapping bats all over Georgia". Savannah Now. 19 May 2016. Retrieved 21 May 2016.

- "Bats affected by WNS". White-Nose Syndrome. Retrieved 22 October 2021.

- "Unexplained "White Nose" Disease Killing Northeast Bats". Environment News Service. 2008-01-31. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- Frick WF, Pollock JF, Hicks AC, Langwig KE, Reynolds DS, Turner GG, Butchkoski CM, Kunz TH (August 2010). "An emerging disease causes regional population collapse of a common North American bat species". Science. 329 (5992): 679–82. Bibcode:2010Sci...329..679F. doi:10.1126/science.1188594. PMID 20689016. S2CID 43601856.

- Auteri GG, Knowles LL (February 2020). "Decimated little brown bats show potential for adaptive change". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 3023. Bibcode:2020NatSR..10.3023A. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-59797-4. PMC 7033193. PMID 32080246.

- "Cute but contagious" The Economist, May 21, 2009

- Hill M (30 January 2008). "Bat Deaths in NY, VT. Baffle Experts". Associated Press. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- Mann B (2008-02-19). "Northeast Bat Die-Off Mirrors Honeybee Collapse" (audio). All Things Considered. National Public Radio. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- Blehert DS, Hicks AC, Behr M, Meteyer CU, Berlowski-Zier BM, Buckles EL, Coleman JT, Darling SR, Gargas A, Niver R, Okoniewski JC, Rudd RJ, Stone WB (January 2009). "Bat white-nose syndrome: an emerging fungal pathogen?". Science. 323 (5911): 227. doi:10.1126/science.1163874. PMID 18974316. S2CID 23869393.

- "Newly Identified Fungus Implicated In White-nose Syndrome". Science Daily. 2008-10-31. Retrieved 2009-10-25.

- "Bats Affected by WNS". White-nose Syndrome Response Team. Retrieved 11 March 2020.

- "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". Iucnredlist.org. Retrieved 2022-08-10.

- US Fish & Wildlife Service, Northeast Region, "White-Nose Syndrome in bats: Something is killing our bats." http://www.fws.gov/northeast/white_nose.html (accessed April 14, 2009)

- Tennessee Valley Authority (22 April 2013). "WNS in Alabama Updates | Alabama Bat Working Group". Alabamabatwg.wordpress.com. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- Warnecke L, Turner JM, Bollinger TK, Lorch JM, Misra V, Cryan PM, Wibbelt G, Blehert DS, et al. (May 2012). "Inoculation of bats with European Geomyces destructans supports the novel pathogen hypothesis for the origin of white-nose syndrome". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (18): 6999–7003. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.6999W. doi:10.1073/pnas.1200374109. PMC 3344949. PMID 22493237.

- Verant ML, Boyles JG, Waldrep W, Wibbelt G, Blehert DS (2012). "Temperature-dependent growth of Geomyces destructans, the fungus that causes bat white-nose syndrome". PLOS ONE. 7 (9): e46280. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...746280V. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0046280. PMC 3460873. PMID 23029462.

- Lorch JM, Meteyer CU, Behr MJ, Boyles JG, Cryan PM, Hicks AC, Ballmann AE, Coleman JT, Redell DN, Reeder DM, Blehert DS (October 2011). "Experimental infection of bats with Geomyces destructans causes white-nose syndrome". Nature. 480 (7377): 376–8. Bibcode:2011Natur.480..376L. doi:10.1038/nature10590. PMID 22031324. S2CID 4381156.

- Minnis AM, Lindner DL (September 2013). "Phylogenetic evaluation of Geomyces and allies reveals no close relatives of Pseudogymnoascus destructans, comb. nov., in bat hibernacula of eastern North America". Fungal Biology. 117 (9): 638–49. doi:10.1016/j.funbio.2013.07.001. PMID 24012303.

- Puechmaille SJ, Verdeyroux P, Fuller H, Gouilh MA, Bekaert M, Teeling EC (February 2010). "White-nose syndrome fungus (Geomyces destructans) in bat, France" (PDF). Emerging Infectious Diseases. 16 (2): 290–3. doi:10.3201/eid1602.091391. PMC 2958029. PMID 20113562.

- Young S (2011-10-26). ""Culprit behind bat scourge confirmed" Nature". Nature. doi:10.1038/news.2011.613. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- Zukal J, Bandouchova H, Brichta J, Cmokova A, Jaron KS, Kolarik M, Kovacova V, Kubátová A, Nováková A, Orlov O, Pikula J, Presetnik P, Šuba J, Zahradníková A, Martínková N (January 2016). "White-nose syndrome without borders: Pseudogymnoascus destructans infection tolerated in Europe and Palearctic Asia but not in North America". Scientific Reports. 6: 19829. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619829Z. doi:10.1038/srep19829. PMC 4731777. PMID 26821755.

- Fritze M, Puechmaille SJ (2018). "Identifying unusual mortality events in bats: a baseline for bat hibernation monitoring and white-nose syndrome research". Mammal Review. 48 (3): 224–228. doi:10.1111/mam.12122. ISSN 1365-2907. S2CID 90460365.

- Wibbelt G, Puechmaille SJ, Ohlendorf B, Mühldorfer K, Bosch T, Görföl T, Passior K, Kurth A, Lacremans D, Forget F (2013-09-04). "Skin lesions in European hibernating bats associated with Geomyces destructans, the etiologic agent of white-nose syndrome". PLOS ONE. 8 (9): e74105. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...874105W. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0074105. PMC 3762782. PMID 24023927.

- Drees KP, Lorch JM, Puechmaille SJ, Parise KL, Wibbelt G, Hoyt JR, Sun K, Jargalsaikhan A, Dalannast M, Palmer JM, Lindner DL, Marm Kilpatrick A, Pearson T, Keim PS, Blehert DS, Foster JT (December 2017). "Phylogenetics of a Fungal Invasion: Origins and Widespread Dispersal of White-Nose Syndrome". mBio. 8 (6): e01941–17. doi:10.1128/mBio.01941-17. PMC 5727414. PMID 29233897.

- Leopardi S, Blake D, Puechmaille SJ (March 2015). "White-Nose Syndrome fungus introduced from Europe to North America". Current Biology. 25 (6): R217–R219. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.047. PMID 25784035.

- Constantine DG (January 2003). "Geographic translocation of bats: known and potential problems". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 9 (1): 17–21. doi:10.3201/EID0901.020104. PMC 2873759. PMID 12533276.

- "Bureau Land Management: "How is White-Nose Syndrome Spread?"". Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- "White-Nose Syndrome". www.blm.gov. 2014-11-28. Archived from the original on 2016-03-01. Retrieved 2016-02-22.

- Janicki, Amanda F.; Frick, Winifred F.; Kilpatrick, A. Marm; Parise, Katy L.; Foster, Jeffrey T.; McCracken, Gary F. (2015). "Efficacy of visual surveys for white-nose syndrome at bat hibernacula". PLOS ONE. 10 (7): e0133390. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1033390J. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0133390. PMC 4509758. PMID 26197236.

- "A National Plan for Assisting States, Federal Agencies, and Tribes in Managing White-Nose Syndrome in Bats" (PDF). US Fish and Wildlife Service. May 2011. p. 21. Retrieved 10 January 2015.

- "New treatment offers hope for bats battling white nose syndrome". Science News for Students. 26 July 2019. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- Verant ML, Meteyer CU, Speakman JR, Cryan PM, Lorch JM, Blehert DS (December 2014). "White-nose syndrome initiates a cascade of physiologic disturbances in the hibernating bat host". BMC Physiology. 14 (10): 10. doi:10.1186/s12899-014-0010-4. PMC 4278231. PMID 25487871.

- "White Nose Syndrome; Could cave dwelling bat species become extinct in our lifetime?". Bat Conservation and Management, Inc. Archived from the original on 2009-02-25. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- "Bat affliction found in Vermont and Massachusetts caves". Newsday. 15 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-02-20.

- http://www.nashuatelegraph.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20090223/NEWS02/302239991%5B%5D

- Kosack J (2009). "White-nose syndrome surfaces in Pennsylvania". Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- "White-Nose Syndrome Statements Archive". Dgif.virginia.gov. 2009-04-02. Archived from the original on 2014-07-31. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- Maryland Department of Natural Resources (March 18, 2010). "White Nose Syndrome Confirmed In Bats From Western Maryland Cave" (PDF). White-Nose Syndrome. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- "White-Nose Syndrome in Missouri | Missouri Department of Conservation". Mdc.mo.gov. Archived from the original on 2013-01-06. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (March 19, 2010). "White Nose Syndrome Detected In Ontario Bats". Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 2010-03-19.

- Smith C. "Bat in Clarksville's Dunbar Cave with deadly fungus may be migrant". The Leaf-Chronicle. Retrieved 2010-03-24.

- "White-nose Syndrome Detected in Ohio". Ohio DNR. 2011-03-30. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- "Newsroom". State of Indiana. 2011-02-01. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- "WNS spreads in Kentucky". White-Nose Syndrome. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- "White Nose Syndrome". Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife.

- "Early Signs of White Nose Syndrome Spreading to Bats". White-Nose Syndrome. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- "White-Nose Syndrome detected in Delaware bats". DNRec.delaware.gov. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- Arkansas Game and Fish Commission (28 July 2013). "Fungus that kills bats prompts continued precautions at Arkansas caves" (PDF).

- Galbincea P (2012-02-16). "Deadly white-nose syndrome found on bats in Cuyahoga and Geauga County parks". The Plain Dealer. Retrieved 2012-02-17.

- Acadia National Park (20 March 2012). "Bat Disease, White-Nose Syndrome, Confirmed in Acadia National Park: Not Harmful to Humans, but Deadly to Bats" (PDF). Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2012-03-21. (PDF linked from White-Nose Syndrome.org)

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources News Release (12 March 2013). "Disease Deadly to Bats Confirmed in Georgia". Archived from the original on 22 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- South Carolina Department of Natural Resources News Release (2013-03-11). "Bat disease white-nose syndrome confirmed in South Carolina". Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- Illinois Department of Natural Resources News Release (2013-02-28). "White-Nose Syndrome Confirmed in Illinois Bats" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-03-26.

- "Bat white-nose syndrome confirmed on Prince Edward Island". CBC News. 2013-02-27. Retrieved 2014-03-15.

- "Deadly bat disease detected in single Wisconsin site; State joins 23 others in confirming white-nose syndrome". Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 10 April 2014.

- "Detroit Free Press article". Detroit Free Press. 11 April 2014. p. 1A.

- "Oklahoma removed from list of suspected bat fungus areas". Oklahoma Department of Wildlife Conservation. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- "Where is it now?". White-Nose Syndrome. Retrieved 2015-01-09.

- "Deadly Bat Fungus in Washington State Likely Originated in Eastern U.S." www.usgs.gov. Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- Froschauer A (May 11, 2017). "Researchers work to stop the spread of white-nose syndrome in Washington". white-nose syndrome.org. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved May 12, 2017.

- "Fungus that Causes White-nose Syndrome in Bats Detected in Texas". Texas Parks and Wildlife. Texas Parks and Wildlife. Retrieved 4 April 2007.

- Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism (2 April 2018). "Bat Disease Detected in Kansas". KSAL.com. Rocking M Media. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

- "Province of Manitoba | News Releases | White-nose Bat Syndrome Found in Manitoba". Province of Manitoba. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- "Fungus that causes bat-killing disease White-nose Syndrome is expanding in Texas". Bat Conservation International. Retrieved 2019-07-05.

- ohtadmin (2021-04-30). "First Montana case of white-nose syndrome detected in Fallon County bat - Fallon County Times". Fallon County Times -. Retrieved 2022-04-29.

- Lindner DL, Gargas A, Lorch JM, Banik MT, Glaeser J, Kunz TH, Blehert DS (2011-03-18). "DNA-based detection of the fungal pathogen Geomyces destructans in soils from bat hibernacula". Mycologia. 103 (2): 241–6. doi:10.3852/10-262. PMID 20952799. S2CID 17331158.

- WNS Decontamination Team. "National White-Nose Syndrome Decontamination Protocol v 06.25.2012" (PDF).

- Geboy R. "National Decontamination Protocol Update" (PDF). Midwest Regional WNS Coordinator, US Fish & Wildlife Service.

- "Something is killing our bats: The white-nose syndrome mystery". US Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- Munger E (2008-02-14). "Group asking cavers to keep out". Daily Gazette. Retrieved 2008-02-14.

- "DEC Reminds the Public to Avoid Seasonal Caves and Mines to Protect Bat Populations". New York State Department of Environmental Conservation. 28 December 2016. Retrieved 1 November 2016.

- Hoyt, Joseph R.; Langwig, Kate E.; White, J. Paul; Kaarakka, Heather M.; Redell, Jennifer A.; Parise, Katy L.; Frick, Winifred F.; Foster, Jeffrey T.; Kilpatrick, A. Marm (24 June 2019). "Field trial of a probiotic bacteria to protect bats from white-nose syndrome". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 9158. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.9158H. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-45453-z. PMC 6591354. PMID 31235813.

External links

- Species Profile - White-Nose Syndrome, National Invasive Species Information Center, United States National Agricultural Library. Lists general information and resources for White-Nose Syndrome.

- White-Nose Syndrome Response Team

- White Nose Syndrome: The mystery fungus killing our bats, a comprehensive article from Wild Things Sanctuary

- Invasive Species Program: White-Nose Syndrome, United States Geological Survey

- Testimony before the US House Committee on Natural Resources on June 4, 2009

- WNS News from the National Speleological Society

- White-nose Syndrome: A Deadly Disease, Bat Conservation International