William Stoughton (judge)

William Stoughton (1631 – July 7, 1701) was a colonial magistrate and administrator in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. He was in charge of what have come to be known as the Salem Witch Trials, first as the Chief Justice of the Special Court of Oyer and Terminer in 1692, and then as the Chief Justice of the Superior Court of Judicature in 1693. In these trials he controversially accepted spectral evidence (based on supposed demonic visions). Unlike some of the other magistrates, he never admitted to the possibility that his acceptance of such evidence was in error.

William Stoughton | |

|---|---|

Portrait by an unknown artist, c. 1700 | |

| Acting Governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay | |

| In office December 4, 1694 – May 26, 1699 | |

| Preceded by | Sir William Phips |

| Succeeded by | Earl of Bellomont |

| In office July 22, 1700 – July 7, 1701 | |

| Preceded by | Earl of Bellomont |

| Succeeded by | Massachusetts Governor's Council (acting) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1631 Kingdom of England or Massachusetts Bay Colony (accounts differ) |

| Died | July 7, 1701 (aged 69–70) Dorchester, Suffolk County, Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Signature | |

After graduating from Harvard College in 1650, he continued religious studies in England, where he also preached. Returning to Massachusetts in 1662, he chose to enter politics instead of the ministry. An adept politician, he served in virtually every government through the period of turmoil in Massachusetts that encompassed the revocation of its first charter in 1684 and the introduction of its second charter in 1692, including the unpopular rule of Sir Edmund Andros in the late 1680s. He served as lieutenant governor of the province from 1692 until his death in 1701, acting as governor (in the absence of an appointed governor) for about six years. He was one of the province's major landowners, partnering with Joseph Dudley and other powerful figures in land purchases, and it was for him that the town of Stoughton, Massachusetts was named.

Early life

William Stoughton was born in 1631 to Israel Stoughton and Elizabeth Knight Stoughton. The exact location of his birth is uncertain, because there is no known birth or baptismal record for him, and the date when his parents migrated from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony is not known with precision. What is known is that by 1632 the Stoughtons were in the colony, where they were early settlers of Dorchester, Massachusetts.[1]

Stoughton graduated from Harvard College in 1650 with a degree in theology. He intended to become a Puritan minister and traveled to England, where he continued his studies in New College, Oxford. He graduated with an M.A. in theology in 1653.[2] Stoughton was a pious preacher who believed in the "Lord's promise and expectations of great things."[3] England was at the time under Puritan Commonwealth Rule, although 1653 was the year Oliver Cromwell dissolved Parliament, beginning The Protectorate.[4] Stoughton preached in Sussex, and after Charles II was restored to the throne in 1660, Stoughton lost his position in the crackdown on religious dissenters that followed.[5]

Politics and land development

With little prospect for another position in England, Stoughton returned to Massachusetts in 1662.[5] He preached on several occasions at Dorchester and Cambridge, but refused offers of permanent ministerial posts. He instead became involved in politics and land development. He served on the colony's council of assistants (a precursor to the idea of a governor's council) almost every year from 1671 to 1686, and represented the colony in the New England Confederation from 1673 to 1677 and 1680 to 1686.[2] In the 1684 election, Joseph Dudley, who had been labelled as an enemy of the colony (along with Stoughton, Bulkley, and others) for his moderate position on colonial charter issues, failed to win reelection to the council. Stoughton, who was reelected by a small majority and was a friend and business partner of Dudley, refused to serve in protest.[6]

In 1676 he was chosen, along with Peter Bulkeley, to be an agent representing colonial interests in England. Their instructions were narrowly tailored. They were authorized to acquire land claims from the heirs of Sir Ferdinando Gorges and John Mason that conflicted with some Massachusetts land claims in present-day Maine. These they acquired for £1,200,[7] incurring the anger of Charles II, who had intended to acquire those claims for the Duke of York.[8] They were unsuccessful in maintaining broader claims made by Massachusetts against other territories of Maine and the Province of New Hampshire. Their limited authority upset the Lords of Trade, who sought to have the colonial laws modified to conform to their policies.[7] The mission of Stoughton and Bulkley did little more than antagonize colonial officials in London because of their hardline stance.[8]

For many years Stoughton and Joseph Dudley were friends, as well as political and business partners.[9] The two worked closely together politically, and engaged in land development together. In the 1680s Stoughton acquired significant amounts of land from the Nipmuc tribe in what is now Worcester County in partnership with Dudley. The partnership included a venture that established Oxford as a place to settle refugee Huguenots.

Dudley and Stoughton used their political positions to ensure that the titles to lands they were interested in were judicially cleared, a practice that also benefited their friends, relatives, and other business partners.[10] Concerning this practice, Crown agent Edward Randolph wrote that it was "impossible to bring titles of land to trial before them where his Majesties's rights are concerned, the Judges also being parties."[11] This was particularly obvious when Stoughton and Dudley were part of a venture to acquire 1 million acres (4,000 km2) of land in the Merrimack River valley. Dudley's council, on which Stoughton and other investors sat, formally cleared that land's title in May 1686.[12]

When Dudley was commissioned in 1686 to temporarily head the Dominion of New England, Stoughton was appointed to his council, and he was then elected by the council as the deputy president.[13] During the administration of Sir Edmund Andros he served as a magistrate and on the council. As a magistrate he was particularly harsh on the town leaders of Ipswich, who had organized tax protests against the dominion government, based on the claim that dominion rule without representation violated the Rights of Englishmen.[14] When Andros was arrested in April 1689 in a bloodless uprising inspired by the 1688 Glorious Revolution in England, Stoughton was one of the signatories to the declaration of the revolt's ringleaders.[15] Despite this statement of support for the popular cause, he was sufficiently unpopular due to his association with Andros that he was denied elective offices.[16] He appealed to the politically powerful Mather family, with whom he still had positive relations. In 1692,[17] when Increase Mather and Sir William Phips arrived from England carrying the charter for the new Province of Massachusetts Bay and a royal commission for Phips as governor, they also brought one for Stoughton as lieutenant governor.[18]

Lieutenant governor and chief justice

Witch trials

When Phips arrived, rumors of witchcraft were running rampant, especially in Salem.[19] Phips immediately appointed Stoughton to head a special tribunal to deal with accusations of witchcraft, and in June appointed him chief justice of the colonial courts, a post he would hold for the rest of his life.[20][21]

In the now-notorious Salem Witch Trials, Stoughton acted as both chief judge and prosecutor. He was particularly harsh on some of the defendants, sending the jury deliberating in the case of Rebecca Nurse back to reconsider its not guilty verdict; after doing so, she was convicted.[20] Many convictions were made because Stoughton permitted the use of spectral evidence, the idea that a demonic vision could only take on the shape or appearance of someone who had made some sort of devilish pact or engaged in witchcraft. Although Cotton Mather argued that this type of evidence was acceptable when making accusations, some judges expressed reservations about its use in judicial proceedings.[22] Stoughton, however, was convinced of its acceptability, and may have influenced other judges to this view.[23] The special court stopped sitting in September 1692.[24]

In November and December 1692 Governor Phips oversaw a reorganization of the colony's courts to bring them into conformance with English practice. The new courts, with Stoughton still sitting as chief justice, began to handle the witchcraft cases in 1693, but were under specific instructions from Phips to disregard spectral evidence. As a result, a significant number of cases were dismissed due to a lack of evidence, and Phips vacated the few convictions that were made. On 3 January 1693 Stoughton ordered the execution of all suspected witches who had been exempted by their pregnancy. Phips denied enforcement of the order.[24] This turn of events angered Stoughton, and he briefly left the bench in protest.[20]

Historian Cedric Cowing suggests that Stoughton's acceptance of spectral evidence was based partly in a need he saw to reassert Puritan authority in the province.[23] Unlike his colleague Samuel Sewall, who later expressed regret for his actions on the bench in the trials, Stoughton never admitted that his actions and beliefs with respect to spectral evidence and the trials were in error.[25]

Acting governor

Stoughton was also involved in overseeing the colonial response to King William's War, which had broken out in 1689. Massachusetts Bay (which included the area now known as Maine) was in the forefront of the war with New France, and its northern frontier communities suffered significantly from French and Indian raids.[26] Governor Phips was frequently in Maine overseeing the construction of defenses there, leaving Stoughton to oversee affairs in Boston.[27] During one such absence, for example, Stoughton was responsible for raising a small force of militia intended to help protect neighboring New Hampshire, which was similarly being devastated by raids.[28] In early 1694 Phips was recalled to London, to answer charges of misconduct. He delayed his departure until November, at which time Stoughton took over as acting governor. Phips died in London in early 1695, before the charges against him were heard.[29]

Stoughton viewed himself as a caretaker, holding the government until the crown appointed a new governor. As a consequence, he gave the provincial assembly a significant degree of autonomy, which, once established, complicated the relationship the assembly had with later governors. He also took relatively few active steps to implement colonial policies, and only did the minimum needed to follow instructions from London. A commentator in the colonial office observed that he was a "good scholar", but that he was "not suited to enforce the Navigation Act".[30]

In 1695 Stoughton protested the actions of French privateers operating from Acadia, who were wreaking havoc in the New England fishing and merchant fleets.[31] In an attempt to counter this activity, he authorized Benjamin Church to organize a raid against Acadia. While Church was recruiting men for the expedition, New France's governor, the comte de Frontenac, organized an expedition to target the English fort at Pemaquid, Maine. Church had still not departed in August 1696 when he learned that the fort had been taken and destroyed.[32] The instructions Stoughton issued to Church were somewhat vague, and he did little more than raid Beaubassin at the top of the Bay of Fundy before returning to Boston. Before Church's return Stoughton organized a second, smaller expedition that unsuccessfully besieged Fort Nashwaak on the Saint John River. The failure of these expeditions highlighted the inadequacies of the provincial forces, and the Massachusetts assembly appealed to London for aid.[33]

Peace between France and England was achieved with the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697, but it did not resolve any issues concerning the Abenakis to the north.[34] As a result, there continued to be tension on the frontier, and disputes over fishing grounds and the use of Acadian territory by New Englanders for drying fish continued. Stoughton and Acadian Governor Joseph Robineau de Villebon exchanged complaints and threats in 1698 over the issue, with Villebon issuing largely empty threats (he lacked the needed resources to execute them) to seize Massachusetts ships and property left in Acadian territory.[35] Stoughton appealed to London for diplomatic assistance, which had some success in reducing tensions.[36]

Stoughton served as acting governor until 1699, while still also serving as chief justice. He remained lieutenant governor during the brief tenure of the Earl of Bellomont as governor, and again became acting governor on the latter's departure in 1700. He was by then in poor health, and accomplished little of note in his final year.[37]

Harvard and the Brattle Street Church

The corporate existence of Harvard College had been thrown into turmoil by the recission of the colonial charter in 1684, upon which the Harvard charter depended. In 1692 the provincial assembly passed a law enacting a new charter for the college, but the Board of Trade vetoed this law in 1696, again throwing the college's existence into jeopardy. Stoughton, then acting governor, made temporary arrangements for the college's governance while the assembly worked to craft a new charter.[38] Ultimately, Harvard's charter problems would not be solved until 1707, when its 1650 charter was revived.[39]

Religious and political differences between factions of directors at Harvard boiled into the open during the late 1690s. Increase Mather, then the president of Harvard, was theologically conservative, while a number of the directors had adopted moderate views, and in these years they began a struggle for control of the college.[40] This split eventually led to the founding in 1698 of Boston's Brattle Street Church, which issued a manifesto explicitly distancing itself from some of the more extreme Puritan practices advocated by Mather and his son, Cotton.[41] Stoughton and a number of other high-profile religious and political figures in the colony stepped in to resolve the dispute.[42] The peace was so successfully brokered that the elder Mather took part in the new church's dedicatory services.[43]

Family and legacy

Stoughton's was given the then-prestigious Green Dragon Tavern for his social status, one of Boston's most significant masonic and historical landmarks in -about- 1676.[44][45] He died at home in Dorchester in 1701, while serving as acting governor,[46] and was buried in the cemetery now known as the Dorchester North Burying Ground.[47] He was a bachelor, and willed a portion of his estate and his mansion to William Tailer, the son of his sister Rebeccah.[48] Tailer, who was twice lieutenant governor and briefly served as acting governor,[49] was buried alongside Stoughton.[50]

The only sermon of Stoughton's to be published was entitled New-Englands True Interest.[51] The sermon was originally delivered at the election of 1668, and was published in 1670.[52] In it he harkened back to the founding of the colony, saying "God sifted a whole Nation that he might send choice Grain over into this Wilderness", but also lamented what he saw as a decline in Massachusetts society, and urged the lay members of society to defer judgment to their clerical elders.[53]

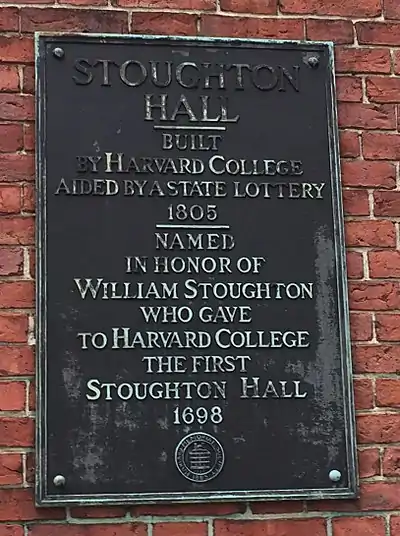

The town of Stoughton, Massachusetts is named in his honor,[2] as is one of the Harvard College dormitories in Harvard Yard. Construction of the first Stoughton Hall, in 1698, was made possible by his £1,000 gift.[54]

Notes

- Anderson, pp 1773–5

- Colby and Sandeman, p. 480

- Felt, p. 424

- Manganiello, p. 43

- Sibley, p. 195

- Lovejoy, p. 155

- Staloff, p. 184

- Lovejoy, p. 140

- Quincy, p. 175

- Martin, pp. 88–97

- Martin, p. 91

- Martin, p. 99

- Lovejoy, p. 180

- Lovejoy, p. 194

- Lovejoy, pp. 241–242

- The Quarterly Register, p. 338

- Quincy, p. 61

- Quincy, p. 178

- Cowing, p. 90

- Cowing, p. 93

- Hurd, pp. xiv, xvi

- Cowing, p. 92

- Cowing, p. 94

- Dunn, pp. 265–267

- The Quarterly Register, p. 339

- Leach, pp. 84–104

- Rawlyk, p. 76

- Leach, p. 105

- Dunn, pp. 268–69.

- Pencak, p. 38

- Rawlyk, p. 80

- Rawlyk, p. 81

- Rawlyk, pp. 82–83

- Morrison, pp. 141–142

- Rawlyk, p. 86

- Rawlyk, p. 87

- Sibley, p. 202

- Quincy, pp. 69–82

- Quincy, p. 277

- Quincy, pp. 127–129

- Quincy, pp. 130–132

- Quincy, p. 134

- Quincy, p. 135

- Old Landmarks and Historic Personages of Boston. Samuel Adams Drake. 1873. page 150.

- A Topographical and Historical Description of Boston. Nathaniel Bradstreet Shurtleff. 1871. Page 605.

- "Biography of William Stoughton". State of Massachusetts. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- Boston Cemetery Department, p. 38

- Clapp, p. 20

- Clapp, pp. 22–24

- Boston Cemetery Department, p. 39

- McWilliams, p. 164

- McWilliams, p. 337

- Staloff, p. 163

- Quincy, p. 180

References

- Anderson, Robert Charles (1995). The Great Migration Begins: Immigrants to New England, 1620–1633. Boston, MA: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 978-0-88082-120-9. OCLC 42469253.

- Boston Cemetery Department (1904). Annual Report of the Cemetery Department, 1903. Boston: City of Boston. OCLC 25503633.

- Clapp, David (1883). The Ancient Proprietors of Jones's Hill, Dorchester. Boston: self-published. OCLC 13392454.

- Colby, Frank; Sandeman, George (1913). Nelson's Encyclopedia. New York: Thomas Nelson. OCLC 8831481.

- Cowing, Cedric (1995). The Saving Remnant: Religion and the Settling of New England. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02138-1. OCLC 30624261.

- Dunn, Richard (1962). Puritans and Yankees: The Winthrop Dynasty of New England. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. OCLC 187083766.

- Felt, Joseph Barlow (1862). The Ecclesiastical History of New England: Comprising Not Only the Religious, But Also Moral, and Other Relations. Boston: Congregational Library Association. p. 424. ISBN 978-0-7905-8263-4. OCLC 22948816.

- Hurd, Duane (1890). History of Middlesex County, Massachusetts. Philadelphia: J. W. Lewis. OCLC 2155461.

- Leach, Douglas (1973). Arms for Empire: A Military history of the British Colonies in North America 1607–1763. New York: Macmillan. OCLC 164624574.

- Lovejoy, David (1987). The Glorious Revolution in America. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 978-0-8195-6177-0. OCLC 14212813.

- Manganiello, Stephen (2004). The Concise Encyclopedia of the Revolutions and Wars of England, Scotland, and Ireland, 1639–1660. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5100-9. OCLC 231993361.

- Martin, John Frederick (1991). Profits in the Wilderness: Entrepreneurship and the Founding of New England Towns in the Seventeenth Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2001-8. OCLC 231347624.

- McWilliams, John (2004). New England's Crises and Cultural Memory: Literature, Politics, History, Religion, 1620–1860. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-511-21107-2. OCLC 144618556.

- Morrison, Kenneth (1984). The Embattled Northeast: the Elusive Ideal of Alliance in Abenaki-Euramerican Relations. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05126-3. OCLC 10072696.

- Pencak, William (1981). War, Politics and Revolution in Provincial Massachusetts. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 978-0-930350-10-9. OCLC 469556813.

- The Quarterly Register. Boston: American Education Society (printed by Perkins and Marvin). 1836.

- Quincy, Josiah (1840). The History of Harvard University. J. Owen. OCLC 60721951.

- Rawlyk, George (1973). Nova Scotia's Massachusetts. Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 978-0-7735-0142-3. OCLC 1371993.

- Sibley, John Langdon (1873). Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Charles William Sever. OCLC 13538569.

- Staloff, Darren (2001). The Making of an American Thinking Class: Intellectuals and Intelligentsia in Puritan Massachusetts. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514982-1. OCLC 469081745.

Further reading

- Miller, Perry; Johnson, Thomas Herbert (2001) [1963]. The Puritans: A Sourcebook of Their Writings. Mineola, NY: Courier Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-41601-4. OCLC 248269294. Contains New-Englands True Interest.

External links

- Biography of William Stoughton (1631-1701) from Stoughton, MA website

- A narrative of the proceedings of sir Edmond Androsse and his complices by William Stoughton, et al. (1691)

- "William Stoughton," pp. 194–208 of Biographical Sketches of Graduates of Harvard University, Vol. 1