Woodlouse

A woodlouse (plural woodlice) is an isopod crustacean from the polyphyletic[2][3][Note 1] suborder Oniscidea within the order Isopoda. They get their name from often being found in old wood.[4]

| Woodlice Temporal range: Early Cretaceous–present, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Clockwise from top right: Ligia oceanica, Hemilepistus reaumuri, Platyarthrus hoffmannseggii and Schizidium tiberianum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Crustacea |

| Class: | Malacostraca |

| Superorder: | Peracarida |

| Order: | Isopoda |

| Suborder: | Oniscidea Latreille 1802[1] |

| Sections | |

| |

The first woodlice were marine isopods which are presumed to have colonised land in the Carboniferous, though the oldest known fossils are from the Cretaceous period.[5] They have many common names and although often referred to as terrestrial isopods, some species live semiterrestrially or have recolonised aquatic environments. Woodlice in the families Armadillidae, Armadillidiidae, Eubelidae, Tylidae and some other genera can roll up into a roughly spherical shape (conglobate) as a defensive mechanism; others have partial rolling ability, but most cannot conglobate at all.

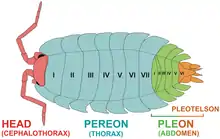

Woodlice have a basic morphology of a segmented, dorso-ventrally flattened body with seven pairs of jointed legs, specialised appendages for respiration and like other peracarids, females carry fertilised eggs in their marsupium, through which they provide developing embryos with water, oxygen and nutrients. The immature young hatch as mancae and receive further maternal care in some species. Juveniles then go through a series of moults before reaching maturity.

While the broader phylogeny of the Oniscideans has not been settled, eleven infraorders/sections are agreed on with 3,937 species validated in scientific literature in 2004[6] and 3,710 species in 2014 out of an estimated total of 5,000–7,000 species extant worldwide.[7] Key adaptations to terrestrial life have led to a highly diverse set of animals; from the marine littoral zone and subterranean lakes to arid deserts and desert slopes 4,725 m (15,500 ft) above sea-level, woodlice have established themselves in most terrestrial biomes and represent the full range of transitional forms and behaviours for living on land.

Woodlice are widely studied in the contexts of evolutionary biology, behavioural ecology and nutrient cycling. They are popular as terrarium pets because of their varied colour and texture forms, conglobating ability and ease of care.

Common names

Common names for woodlice vary throughout the English-speaking world. A number of common names make reference to the fact that some species of woodlice can roll up into a ball. Other names compare the woodlouse to a pig.

Common names include:

- armadillo bug[8]

- billy baker (South Somerset)

- billy button (Dorset)

- boat-builder (Newfoundland, Canada)[9]

- butcher boy or butchy boy (Australia,[10] mostly around Melbourne[11])

- carpenter or cafner (Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada)[12]

- carpet shrimp (Ryedale)

- charlie pig (Norfolk, England)

- cheeselog (Reading, England)[13]

- cheesey wig

- cheesy bobs (Guildford, England)[14]

- cheesy bug (North West Kent, Gravesend, England)[15]

- cheesy lou (Suffolk)

- cheesy papa (Essex)

- chiggy pig (Devon, England)[16][17]

- chisel pig[18]

- chucky pig (Devon, Gloucestershire, Herefordshire, England)[19]

- chuggy pig

- crawley baker (Dorset)

- daddy grampher (North Somerset)

- damp beetle (North East England)

- doodlebug (also used for the larva of an antlion[20] and for the cockchafer)

- fat pigs (Cork, Ireland),

- gramersow (Cornwall, England)[21]

- granny grey (Wales)

- granny grunter (Isle of Man)

- grumper-pig (Bermuda)

- hardback (Humberside, England)

- hobbling Andrew (Oxfordshire, England)

- hobby horse (Isle of Purbeck, Dorset, England)

- hog-louse[22]

- horton bug (Deal, Kent, England)

- humidity bug (Ontario, Canada)

- jomits (Cloneganna)

- menace (Plymouth, Devon)

- mochyn coed (tree pig), pryf lludw (ash bug), granny grey in Wales[23]

- monkey-peas (Kent, England)[5]

- pea bug (Medway, England)[5]

- peasie-bug (Kent, England)[5]

- pennysow (Pembrokeshire, Wales)

- piggy wig

- pill bug (usually applied only to the genus Armadillidium)[24]

- potato bug[25]

- roll up bug[26]

- roly-poly[25]

- saw bug (Dingwall, Nova Scotia)

- scuttlebug (New Zealand)

- slater (Scotland, Ulster, New Zealand and Australia)[27][28][29]

- sour bug (Cambridgeshire)

- sow bug[30]

- water bug

- wood bug (British Columbia, Canada)[31]

- wood-louse

Description and life cycle

The woodlouse has a shell-like exoskeleton, which it must progressively shed as it grows. The moult takes place in two stages;[32] the back half is lost first, followed two or three days later by the front. This method of moulting is different from that of most arthropods, which shed their cuticle in a single process.

A female woodlouse will keep fertilised eggs in a marsupium on the underside of her body, which covers the under surface of the thorax and is formed by overlapping plates attached to the bases of the first five pairs of legs. They hatch into offspring that look like small white woodlice curled up in balls, although initially without the last pair of legs.[32] The mother then appears to "give birth" to her offspring. Females are also capable of reproducing asexually.[33]

Despite being crustaceans like lobsters or crabs, woodlice are said to have an unpleasant taste similar to "strong urine".[33]

Pillbugs and pill millipedes

Pillbugs (woodlice of the family Armadillidiidae, also known as pill woodlice) can be confused with pill millipedes of the order Glomerida.[34] Both of these groups of terrestrial segmented arthropods are about the same size. They live in very similar habitats, and they can both roll up into a ball. Pill millipedes and pillbugs appear superficially similar to the naked eye. This is an example of convergent evolution.

Pill millipedes can be distinguished from woodlice on the basis of having two pairs of legs per body segment instead of one pair like all isopods. Pill millipedes have 12 to 13 body segments and about 18 pairs of legs, whereas woodlice have 11 segments and only seven pairs of legs. In addition, pill millipedes are smoother, and resemble normal millipedes in overall colouring and the shape of the segments.

_-_Ystad-2020.jpg.webp)

Ecology

Many members of Oniscidea live in terrestrial, non-aquatic environments, breathing through trachea-like lungs in their paddle-shaped hind legs (pleopods), called pleopodal lungs. Woodlice need moisture because they rapidly lose water by excretion and through their cuticle, and so are usually found in damp, dark places, such as under rocks and logs, although one species, the desert dwelling Hemilepistus reaumuri, inhabits "the driest habitat conquered by any species of crustacean".[35] They are usually nocturnal and are detritivores, feeding mostly on dead plant matter.

A few woodlice have returned to water. Evolutionary ancient species are amphibious, such as the marine-intertidal sea slater (Ligia oceanica), which belongs to family Ligiidae. Other examples include some Haloniscus species from Australia (family Scyphacidae), and in the northern hemisphere several species of Trichoniscidae and Thailandoniscus annae (family Styloniscidae). Species for which aquatic life is assumed include Typhlotricholigoides aquaticus (Mexico) and Cantabroniscus primitivus (Spain).[36]

Woodlice are eaten by a wide range of insectivores, including spiders of the genus Dysdera, such as the woodlouse spider Dysdera crocata,[30] and land planarians of the genus Luteostriata, such as Luteostriata abundans.[37]

Woodlice are sensitive to agricultural pesticides, but can tolerate some toxic heavy metals, which they accumulate in the hepatopancreas. Thus they can be used as bioindicators of heavy metal pollution.[38]

Evolutionary history

The oldest fossils of woodlice are known from the mid-Cretaceous around 100 million years ago, from amber deposits found in Spain, France and Myanmar, These include a specimen of living genus Ligia from the Charentese amber of France, the genus Myanmariscus from the Burmese amber of Myanmar, which belongs to the Synocheta and likely the Styloniscidae,[39] Eoligiiscus tarraconensis which belongs to the family Ligiidae, Autrigoniscus resinicola which belongs to the family Trichoniscidae, and Heraclitus helenae which possibly belongs to Detonidae all from Spanish amber,[40] and indeterminate specimens Charentese amber.[5][39] The widespread distribution and diversification apparent of woodlice in the mid-Cretaceous implies that the origin of woodlice predates the breakup of Pangaea, likely during the Carboniferous.[5]

As pests

Although woodlice, like earthworms, are generally considered beneficial in gardens for their role in controlling certain pests,[41] producing compost and overturning the soil, they have also been known to feed on cultivated plants, such as ripening strawberries and tender seedlings.[42]

Woodlice can also invade homes en masse in search of moisture and their presence can indicate dampness problems.[43] They are not generally regarded as a serious household pest as they do not spread malady and do not damage sound wood or structures. They can be easily removed with the help of vacuum cleaners, chemical sprays, insect repellents, and insect killers,[44] or by removing the damp.

As pets

Woodlice have become a popular, low-maintenance household pet for children as well as a hobby for invertebrate and insect enthusiasts or collectors.[45] Porcellionidae (sowbugs) and Armadillidae (pillbugs) are seen often as they are the most common terrestrial isopods in Europe and North America.[46]

The isopod community has many resources for the care of the species.[47][48][49] Many sites sell isopods for starting a colony, and to keep a bioactive vivarium clean. Isopods are also a popular species at reptile or invertebrate conventions either sold as pets or micro-feeders.

Morphs and varieties

Amongst those who keep woodlice as pets, many species are bred for a certain coloration or variety of a species and are often recognized by a nickname that corresponds with their variety.

Popular varieties include Dalmatian (Porcellio scaber), Dairy Cow (Porcellio laevis), Montenegro (Armadillidium klugii), Zebra (Armadillidium maculatum), Magic Potion (Armadillidium vulgare), Powder Blue (Porcellionides pruinosus), Panda King (Cubaris sp.), Tricolor (Merulanella sp.), and Rubber Ducky (Cubaris sp.). The Rubber Ducky variety currently proves to be one of the most desired and yet most expensive pillbug isopod to date, with a purchase of 6 individual specimens costing over one-hundred dollars on most shop sites. The Rubber Ducky is popular likely due to its rarity and cute or innocent appearance of a duck face, having yellow bands across the back and front of its body. All Cubaris species have this duck-billed shape on the head, but the Rubber Ducky variety has a coincidental coloring that lines up perfectly with this shape.

Many varieties also have sub-varieties that are even more rare or uncommon, such as the orange mutation or variant of Orange Dalmatian (Dalmatian), Powder Orange (Powder Blue), Pink Ducky (Rubber Ducky), and Orange Koi (Koi) which could be bred with by combining their solid orange variants with the variants in the parentheticals.[50] Other sub-varieties include the Japanese line of Magic Potion, White Ducky, Champagne and Yellow versions of Zebra, Albinos and T-albinos, and many more.

There are some terrestrial isopods, though very few, that have been known to be parthenogenic. More specifically, dwarf whites, but it is unclear whether other varieties such as dwarf purple produce the same. Because of this parthenogenesis, they reproduce quickly and can be great for use as pets or feeders in vivariums.[51]

Some coloration descriptions can be used to identify multiple species, such as Orange Dalmatian, a color-pattern combination seen in both Armadillidium vulgare and Porcellio scaber.

Orange Vigor or Tangerine (Armadillidium vulgare), Peach (Armadillidium nasatum), Orange (Porcellio laevis), Orange (Armadillidium werneri), Orange (Porcellio expansus), Orange, Orange Ember, or Spanish Orange (Porcellio scaber), Maple Orange (Oniscus asellus), Kumquat (Agabiformius lentus), and Persimmon (Venezillo parvus) are all simply orange varieties of their species, and when combined with other varieties of their species can make even more uncommon colorations unique to them.[52]

Some unique species of woodlouse include the spiny isopods, though not much is known about them and there are only a few of them easily accessible for purchase online. These occasionally include Cristarmadillidium muricatum and a species from Thailand often referred to as simply "Thailand Spiny".[53]

In the British Isles

Classification

- Infraorder/Section Diplocheta

- Ligiidae

- Infraorder Holoverticata

- Section: Tylida

- Tylidae

- Section: Microcheta

- Mesoniscidae

- Section: Synocheta

- Buddelundiellidae

- Schoebliidae

- Styloniscidae

- Titaniidae

- Trichoniscidae

- Turanoniscidae

- Section: Crinocheta

- Agnaridae

- Alloniscidae

- Armadillidae

- Armadillidiidae

- Balloniscidae

- Bathytropidae

- Berytoniscidae

- Cylisticidae

- Delatorreiidae

- Detonidae

- Eubelidae

- Halophilosciidae

- Olibrinidae

- Oniscidae

- Philosciidae

- Platyarthridae

- Porcellionidae

- Pudeoniscidae

- Rhyscotidae

- Scleropactidae

- Scyphacidae

- Spelaeoniscidae

- Stenoniscidae

- Tendosphaeridae

- Trachelipodidae

See also

- Invertebrate iridescent virus 31 – a species of virus hosted by woodlice

Notes

- The current consensus is that Oniscidea is actually triphyletic

References

- WORMS

- Dimitriou, Andreas C.; Taiti, Stefano; Sfenthourakis, Spyros (December 6, 2019). "PGenetic evidence against monophyly of Oniscidea implies a need to revise scenarios for the origin of terrestrial isopods". Scientific Reports. Nature. 9 (1): 18508. Bibcode:2019NatSR...918508D. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-55071-4. PMC 6898597. PMID 31811226.

- Lins, Luana S. F.; Ho, Simon Y. W.; Lo, Nathan (October 15, 2017). "An evolutionary timescale for terrestrial isopods and a lack of molecular support for the monophyly of Oniscidea (Crustacea: Isopoda)". Organisms Diversity & Evolution. Springer. 17 (4): 813–820. doi:10.1007/s13127-017-0346-2. S2CID 6580830.

- "woodlouse". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved April 14, 2020.

- Broly, Pierre; Deville, Pascal; Maillet, Sébastien (December 23, 2012). "The origin of terrestrial isopods (Crustacea: Isopoda: Oniscidea)". Evolutionary Ecology. 27 (3): 461–476. doi:10.1007/s10682-012-9625-8. ISSN 0269-7653. S2CID 17595540.

- Helmut Schmalfuss (2003). "World catalog of terrestrial isopods (Isopoda: Oniscidea)—revised and updated version" (PDF). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie A. 654: 341 pp.

- Sfendourakis, Spyros; Taiti, Stefano (July 30, 2015). "Patterns of taxonomic diversity among terrestrial isopods". ZooKeys (515): 13–25. doi:10.3897/zookeys.515.9332. ISSN 1313-2970. PMC 4525032. PMID 26261437.

- Dale Mayer (2010). The Complete Guide to Companion Planting: Everything You Need to Know to Make Your Garden Successful. Atlantic Publishing Company. p. 88. ISBN 9781601383457.

- "Dictionary of Newfoundland English - boat n". Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- "Bugs Bugs Bugs!" (PDF). Museum Victoria. Retrieved March 30, 2010.

- "Australian Word Map". Macquarie Dictionary. Macmillan Publishers, Australia. 2014. Retrieved February 8, 2015.

- "Dictionary of Newfoundland English - carpenter n". Dictionary of Newfoundland English. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- Paul Kerswill. "The sound of Reddin". BBC. Retrieved September 17, 2006.

- James Chapple (January 14, 2016). "Everyone in Guildford is calling wood lice 'cheesy bobs' and it's brilliant". Trinity Mirror Group. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- Howe, Ian (2012). Kent Dialect. Bradwell Books. pp. 7, 18. ISBN 9781902674346.

- "BBC Devon: Voices". BBC Devon. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- "365 Urban Species. #093: Woodlouse". The Urban Pantheist. April 3, 2006. Retrieved January 18, 2009.

- Aylward, Steve (March 30, 2021). "The egg-cellent world of invertebrate eggs". Suffolk Wildlife Trust. Retrieved April 8, 2022.

- Barber, A. D. (2015). "Vernacular names of woodlice with particular reference to Devonshire" (PDF). Bulletin of the British Myriapod & Isopod Group. 28: 54–63.

- "Sow bug". Dictionary.com Unabridged (v 1.0.1). 2006. Retrieved August 17, 2006.

- Matthew Francis (2004). Where the People Are: Language and Community in the Poetry of W.S. Graham. Salt Publishing. ISBN 978-1-876857-23-3.

- Oxford English Dictionary 1933: headword Hog-louse

- "Pillbugs". Niles Biological, Inc. Retrieved June 8, 2016.

- Bill Amos (August 10, 2002). "Little armored tanks". Caledonian-Record.

- Bert Vaux & Scott A. Golder. "Dialect Survey". Harvard University. Archived from the original on September 3, 2006. Retrieved September 30, 2006.

- Gail Smith-Arrants (March 20, 2004). "You say potato bug, I say roly-poly, you say…" (PDF). Charlotte Observer.

- Mairi Robinson, ed. (1987). The Concise Scots Dictionary (3rd ed.). Aberdeen: Aberdeen University Press. p. 628. ISBN 978-0-08-028492-7.

- Maria Minor & A. W. Robertson (2006). "Guide to New Zealand soil invertebrates: Isopoda". Massey University. Retrieved May 13, 2007.

- Josh Byrne (2009). "Fact Sheet: Slater Control". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved May 22, 2012.

- Bruce Marlin. "Common Woodlouse, Sow Bug, Pillbug". North American Insects and Spiders. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- "Wood Bug". Vancouver Sun. November 26, 2007. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012.

- Calman, William Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 802.

- "How Now, Sow Bug?," Discover, August 1999, 68.

- "Pill woodlouse (Armadillidium vulgare)". ARKive.org. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved February 13, 2009.

- Rod Preston-Mafham & Ken Preston-Mafham (1993). "Crustacea. Woodlice, crabs". The Encyclopedia of Land Invertebrate Behavior. MIT Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-262-16137-4.

- Ivo Karaman (2003). "Macedonethes stankoi n. sp., a rhithral oniscidean isopod (Isopoda: Oniscidea: Trichoniscidae) from Macedonia" (PDF). Organisms Diversity & Evolution. 3 (8): 1–15. doi:10.1078/1439-6092-00054.

- Prasniski, M. E. T.; Leal-Zanchet, A. M. (2009). "Predatory behavior of the land flatworm Notogynaphallia abundans (Platyhelminthes: Tricladida)". Zoologia (Curitiba). 26 (4): 606. doi:10.1590/S1984-46702009005000011.

- Paoletti, Maurizio G.; Hassall, Mark (1999). "Woodlice (Isopoda: Oniscidea): their potential for assessing sustainability and use as bioindicators". Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment. 74 (1–3): 157–165. doi:10.1016/S0167-8809(99)00035-3.

- Broly, Pierre; Maillet, Sébastien; Ross, Andrew J. (July 2015). "The first terrestrial isopod (Crustacea: Isopoda: Oniscidea) from Cretaceous Burmese amber of Myanmar". Cretaceous Research. 55: 220–228. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2015.02.012.

- Sánchez-García, Alba; Peñalver, Enrique; Delclòs, Xavier; Engel, Michael S. (August 6, 2021). "Terrestrial Isopods from Spanish Amber (Crustacea: Oniscidea): Insights into the Cretaceous Soil Biota". American Museum Novitates (3974). doi:10.1206/3974.1. hdl:2445/182822. ISSN 0003-0082. S2CID 236936902.

- Bailey, Pat (March 15, 1999). "Humble Roly-Poly Bug Thwarts Stink Bugs in Farms, Gardens". UC Davis News Service.

- Phillip E. Sloderbeck (2004). "Pillbugs and sowbugs" (PDF). Kansas State University.

- "Sow Bugs". Pestcontrolcanada.com. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- "How To Get Rid Of Woodlice in Home Naturally | With Best Woodlice Killer". June 3, 2020.

- "Pet Isopods: The great crawling! -". February 16, 2021. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- "Pillbugs and Sowbugs (Land Isopods)". Missouri Department of Conservation. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- "Isopod Food - How to feed them right. -". August 24, 2018. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- "Isopod keeping reports -". Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- "Isopods Archives". Josh's Frogs How-To Guides. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- Bug, Smug (March 20, 2021). "The Orange Mutation in Different Isopod Species". Smugbug. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- Bug, Smug (August 29, 2020). "The Use of Dwarf White Isopods in the Reptile Hobby". Smugbug. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- Bug, Smug (March 20, 2021). "The Orange Mutation in Different Isopod Species". Smugbug. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- "Other Isopods (Merulanella, etc.) Archive -". Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- Richard Brusca (August 6, 1997). "Isopoda". Tree of Life Web Project.

- Helmut Schmalfuss (2003). "World catalog of terrestrial isopods (Isopoda: Oniscidea) – revised and updated version" (PDF). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie A. 654: 341 pp.

- Paul T. Harding & Stephen L. Sutton (1985). Woodlice in Britain and Ireland: distribution and habitat (PDF). Abbots Ripton, Huntingdon, Institute of Terrestrial Ecology. p. 151. ISBN 0-904282-85-6. accessed through the NERC Open Access Research Archive (NORA)

- "Walking with Woodlice". Imperial College London.

Paul T. Harding & Stephen L. Sutton (1985). Woodlice in Britain and Ireland: distribution and habitat (PDF). Abbots Ripton, Huntingdon, Institute of Terrestrial Ecology. p. 151. ISBN 0-904282-85-6. accessed through the NERC Open Access Research Archive (NORA)

External links

Further reading

- Helmut Schmalfuss (2003). "World catalog of terrestrial isopods (Isopoda: Oniscidea)—revised and updated version" (PDF). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie A. 654: 341 pp. (lists all validated species of Oniscidea published up to the end of 2004)

- Helmut Schmalfuss; Karin Wolf-Schwenninger (2002). "A bibliography of terrestrial isopods (Crustacea, Isopoda, Oniscidea)—revised and updated version" (PDF). Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie A. 639: 120 pp. (lists most scientific publications on the biology of Oniscidea published in a European language until the year 2004.)

- Christian Schmidt & Andreas Leistikow (2004). "Catalogue of the terrestrial Isopoda (Crustacea: Isopoda: Oniscidea)" (PDF). Steenstrupia. 28 (1): 1–118. (lists all genera published up to the end of 2001)