−1

In mathematics, −1 (also known as negative one or minus one) is the additive inverse of 1, that is, the number that when added to 1 gives the additive identity element, 0. It is the negative integer greater than negative two (−2) and less than 0.

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cardinal | −1, minus one, negative one | ||||

| Ordinal | −1st (negative first) | ||||

| Arabic | −١ | ||||

| Chinese numeral | 负一,负弌,负壹 | ||||

| Bengali | −১ | ||||

| Binary (byte) |

| ||||

| Hex (byte) |

| ||||

Algebraic properties

Multiplying a number by −1 is equivalent to changing the sign of the number – that is, for any x we have (−1) ⋅ x = −x. This can be proved using the distributive law and the axiom that 1 is the multiplicative identity:

- x + (−1) ⋅ x = 1 ⋅ x + (−1) ⋅ x = (1 + (−1)) ⋅ x = 0 ⋅ x = 0.

Here we have used the fact that any number x times 0 equals 0, which follows by cancellation from the equation

- 0 ⋅ x = (0 + 0) ⋅ x = 0 ⋅ x + 0 ⋅ x.

In other words,

- x + (−1) ⋅ x = 0,

so (−1) ⋅ x is the additive inverse of x, i.e. (−1) ⋅ x = −x, as was to be shown.

Square of −1

The square of −1, i.e. −1 multiplied by −1, equals 1. As a consequence, a product of two negative numbers is positive.

For an algebraic proof of this result, start with the equation

- 0 = −1 ⋅ 0 = −1 ⋅ [1 + (−1)].

The first equality follows from the above result, and the second follows from the definition of −1 as additive inverse of 1: it is precisely that number which when added to 1 gives 0. Now, using the distributive law, it can be seen that

- 0 = −1 ⋅ [1 + (−1)] = −1 ⋅ 1 + (−1) ⋅ (−1) = −1 + (−1) ⋅ (−1).

The third equality follows from the fact that 1 is a multiplicative identity. But now adding 1 to both sides of this last equation implies

- (−1) ⋅ (−1) = 1.

The above arguments hold in any ring, a concept of abstract algebra generalizing integers and real numbers.

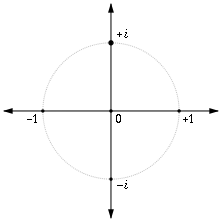

Square roots of −1

Although there are no real square roots of −1, the complex number i satisfies i2 = −1, and as such can be considered as a square root of −1.[1][2] The only other complex number whose square is −1 is −i because there are exactly two square roots of any non‐zero complex number, which follows from the fundamental theorem of algebra. In the algebra of quaternions – where the fundamental theorem does not apply – which contains the complex numbers, the equation x2 = −1 has infinitely many solutions.

Exponentiation to negative integers

Exponentiation of a non‐zero real number can be extended to negative integers. We make the definition that x−1 = 1/x, meaning that we define raising a number to the power −1 to have the same effect as taking its reciprocal. This definition is then extended to negative integers, preserving the exponential law xaxb = x(a + b) for real numbers a and b.

Exponentiation to negative integers can be extended to invertible elements of a ring, by defining x−1 as the multiplicative inverse of x.

A −1 that appears as a superscript of a function does not mean taking the (pointwise) reciprocal of that function, but rather the inverse function of the function. For example, sin−1(x) is a notation for the arcsine function, and in general f −1(x) denotes the inverse function of f(x),. When a subset of the codomain is specified inside the function, it instead denotes the preimage of that subset under the function.

Uses

- In software development, −1 is a common initial value for integers and is also used to show that a variable contains no useful information.

- −1 bears relation to Euler's identity since eiπ = −1.

See also

- Balanced ternary

- Menelaus's theorem

References

- "Imaginary Numbers". Math is Fun. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Imaginary Number". MathWorld. Retrieved 15 February 2021.