Aceh

Aceh (/ˈɑːtʃeɪ/ (![]() listen) AH-chay), officially the Aceh Province (Acehnese: Nanggroë Acèh; Indonesian: Provinsi Aceh) is the westernmost province of Indonesia. It is located on the northernmost of Sumatra island, with Banda Aceh being its capital and largest city. Granted a special autonomous status, Aceh is a religiously conservative territory and the only Indonesian province practicing the Sharia law officially. There are ten indigenous ethnic groups in this region, the largest being the Acehnese people, accounting for approximately 80% to 90% of the region's population.

listen) AH-chay), officially the Aceh Province (Acehnese: Nanggroë Acèh; Indonesian: Provinsi Aceh) is the westernmost province of Indonesia. It is located on the northernmost of Sumatra island, with Banda Aceh being its capital and largest city. Granted a special autonomous status, Aceh is a religiously conservative territory and the only Indonesian province practicing the Sharia law officially. There are ten indigenous ethnic groups in this region, the largest being the Acehnese people, accounting for approximately 80% to 90% of the region's population.

Aceh | |

|---|---|

Province with special status | |

| Province of Aceh | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Acehnese | Nanggroë Acèh |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): | |

| Motto(s): Pancacita (Kawi) "Five Ideals" | |

| Anthem: Aceh Mulia (Indonesian) "Glorious Aceh" | |

| |

OpenStreetMap  | |

| Coordinates: 05°33′25″N 95°19′34″E | |

| Province status | 7 December 1956[1] |

| Capital and largest city | Banda Aceh |

| Government | |

| • Type | Special autonomous province |

| • Acting Governor | Achmad Marzuki |

| • Legislative | People's Representative Council of Aceh |

| Area | |

| • Total | 58,376.81 km2 (22,539.41 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 11th |

| Elevation | 125 m (410 ft) |

| Highest elevation (Mount Leuser) | 3,466 m (11,371 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population (mid 2021 official estimate)[2] | |

| • Total | 5,333,733 |

| • Rank | 14th |

| • Density | 91/km2 (240/sq mi) |

| • Rank | 20th |

| Demonym | Acehnese[3] |

| Demographics | |

| • Ethnic groups | |

| • Religion |

|

| • Languages |

|

| Time zone | UTC+7 (Indonesia Western Time) |

| GRP per capita | US$2,239.49 |

| GRP rank | 19th (2018) |

| HDI (2021) | |

| HDI rank | 11th (2021) |

| Website | acehprov |

Aceh is where the spread of Islam in Indonesia began, and was a key factor of the spread of Islam in Southeast Asia. Islam reached Aceh (Kingdoms of Fansur and Lamuri) around 1250 AD. In the early 17th century the Sultanate of Aceh was the most wealthy, powerful and cultivated state in the Malacca Straits region. Aceh has a history of political independence and resistance to control by outsiders, including the former Dutch colonists and later the Indonesian government.

Aceh has substantial natural resources of oil and natural gas.[6] Aceh was the closest point of land to the epicenter of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, which devastated much of the western coast of the province. Approximately 170,000 Indonesians were killed or went missing in the disaster.[7] The disaster helped precipitate the peace agreement between the government of Indonesia and the terrorist-separatist group of Free Aceh Movement.

Etymology

Aceh was first known as Aceh Darussalam (1511–1945). Upon its formation in 1956 it bore the name Aceh before being renamed to the Daerah Istimewa Aceh (Aceh Special Region; 1959–2001), Nanggroë Aceh Darussalam (2001–2009), and back to Aceh (2009–present). In the past it was also spelled as Acheh, Atjeh, and Achin.[8]

History

Prehistory

According to several archaeological findings, the first evidence of human habitation in Aceh is from a site near the Tamiang River where shell middens are present. Stone tools and faunal remains were also found on the site. Archeologists believe the site was first occupied around 10,000 BCE.[9]

Pre-Islamic Aceh

The history of Aceh stretches back to the Lambri Kingdom. Several documented references indicate that Hindu-Buddhist culture existed in the area before its Islamization. The Hindu-Buddhist culture in Aceh was not as evident or well established as in other parts of Indonesia.[10][11]

The people of Lambri were described by Marco Polo as "idolaters", who had a Maharaja as their ruler, a king in the Hindu political structure, likely meaning they were Hindus, Buddhists, or a combination thereof.[12]

The inscription at Tanjore of Rajendra Chola I documents the conquest of a land called "llämuridesam", located at the northern tip of Sumatra. The Nagarakritagama documents the possessions of the Imperial Majapahit, and states that they control Barat, identified as the western coast of Aceh. Chinese records indicate that Aceh was under the control of the Sriwijaya.[13]

Though many temples were left abandoned or converted into mosques, such as the Indrapuri Old Mosque,[14] some evidence remains, such as the head of a stone sculpture of Avalokiteshvara Boddhisattva was discovered in Aceh. Images of Amitabha Buddhas adorn his crown in front and on each side. Srivijayan art estimated 9th-century CE collection of National Museum of Indonesia, Jakarta. One of the few structural remains is the Indra Patra fort, which has several Hindu shrines.[15] Historic names such as Indrapurba, Indrapurwa, Indrapatra, and Indrapuri, which refer to the God Indra, also indicate that Hinduism had a lasting and significant presence in this land.

Beginnings of Islam in Southeast Asia

Evidence concerning the initial coming and subsequent establishment of Islam in Southeast Asia is thin and inconclusive. The historian Anthony Reid has argued that the region of the Cham people on the south-central coast of Vietnam was one of the earliest Islamic centers in Southeast Asia. Furthermore, as the Cham people fled the Vietnamese, one of the earliest locations that they established a relationship was with Aceh.[16] Furthermore, it is thought that one of the earliest centers of Islam was in the Aceh region. When Venetian traveller Marco Polo passed by Sumatra on his way home from China in 1292 he found that Peureulak was a Muslim town while nearby 'Basma(n)' and 'Samara' were not. 'Basma(n)' and 'Samara' are often said to be Pasai and Samudra but evidence is inconclusive. The gravestone of Sultan Malik as-Salih, the first Muslim ruler of Samudra, has been found and is dated AH 696 (AD 1297). This is the earliest clear evidence of a Muslim dynasty in the Indonesia-Malay area and more gravestones from the 13th century show that this region continued under Muslim rule. Ibn Batutah, a Moroccan traveller, passing through on his way to China in 1345 and 1346, found that the ruler of Samudra was a follower of the Shafi'i school of Islam.[17]

After the initial appearance of Islam in Aceh, it further spread into the coastal regions by the 15th century.[10] Aceh soon became a cultural and scholastic Islamic center throughout Southeast Asia. It also became wealthy because it was a center of extensive trade.[18]

The Portuguese apothecary Tome Pires reported in his early 16th-century book Suma Oriental that most of the kings of Sumatra from Aceh through Palembang were Muslim. At Pasai, in what is now the North Aceh Regency, there was a thriving international port. Pires attributed the establishment of Islam in Pasai to the 'cunning' of the Muslim merchants. The ruler of Pasai, however, had not been able to convert the people of the interior.[19]

Sultanate of Aceh

The Sultanate of Aceh was established by Sultan Ali Mughayat Syah in 1511.

In 1584–88 the Bishop of Malacca, D. João Ribeiro Gaio, based on information provided by a former captive called Diogo Gil, wrote the "Roteiro das Cousas do Achem" (Lisboa 1997) – a description of the sultanate.

Later, during its golden era, in the 17th century, its territory and political influence expanded as far as Satun in southern Thailand, Johor in Malay Peninsula, and Siak in what is today the province of Riau. As was the case with most non-Javan pre-colonial states, Acehnese power expanded outward by sea rather than inland. As it expanded down the Sumatran coast, its main competitors were Johor and Portuguese Malacca on the other side of the Straits of Malacca. It was this seaborne trade focus that saw Aceh rely on rice imports from north Java rather than develop self sufficiency in rice production.[20]

After the Portuguese occupation of Malacca in 1511, many Islamic traders passing the Malacca Straits shifted their trade to Banda Aceh and increased the Acehnese rulers' wealth. During the reign of Sultan Iskandar Muda in the 17th century, Aceh's influence extended to most of Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula. Aceh allied itself with the Ottoman Empire and the Dutch East India Company in their struggle against the Portuguese and the Johor Sultanate. Acehnese military power waned gradually thereafter, and Aceh ceded its territory of Pariaman in Sumatra to the Dutch in the 18th century.[21]

By the early 19th century, however, Aceh had become an increasingly influential power due to its strategic location for controlling regional trade. In the 1820s it was the producer of over half the world's supply of black pepper. The pepper trade produced new wealth for the sultanate and for the rulers of many smaller nearby ports that had been under Aceh's control, but were now able to assert more independence. These changes initially threatened Aceh's integrity, but a new sultan Tuanku Ibrahim, who controlled the kingdom from 1838 to 1870, reasserted power over nearby ports.[22]

Under the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 the British ceded their colonial possessions on Sumatra to the Dutch. In the treaty, the British described Aceh as one of their possessions, although they had no actual control over the sultanate. Initially, under the agreement the Dutch agreed to respect Aceh's independence. In 1871, however, the British dropped previous opposition to a Dutch invasion of Aceh, possibly to prevent France or the United States from gaining a foothold in the region. Although neither the Dutch nor the British knew the specifics, there had been rumors since the 1850s that Aceh had been in communication with the rulers of France and of the Ottoman Empire.[22]

Aceh War

Pirates operating from Aceh threatened commerce in the Strait of Malacca; the sultan was unable to control them. Britain was a protector of Aceh and gave the Netherlands permission to eradicate the pirates. The campaign quickly drove out the sultan but the local leaders mobilized and fought the Dutch in four decades of guerrilla war, with high levels of atrocities.[23] The Dutch colonial government declared war on Aceh on 26 March 1873. Aceh sought American help but Washington rejected the request.[22]

The Dutch tried one strategy after another over the course of four decades. An expedition under Major General Johan Harmen Rudolf Köhler in 1873 occupied most of the coastal areas. Köhler's strategy was to attack and take the sultan's palace. It failed. The Dutch then tried a naval blockade, reconciliation, concentration within a line of forts, and lastly passive containment. They had scant success. Reaching 15 to 20 million guilders a year, the heavy spending for failed strategies nearly bankrupted the colonial government.[24] During the course of the war, the Dutch set up the Gouvernment of Atjeh and Dependencies under a governor, although it did not establish wider control of its territory until after 1908.

The Aceh army was rapidly modernized, and Aceh soldiers butchered Köhler (a monument to this atrocity has been built inside Grand Mosque of Banda Aceh). Köhler made some grave tactical errors and the reputation of the Dutch was severely harmed. In recent years, in line with expanding international attention to human rights issues and atrocities in war zones, there has been increasing discussion about some of the recorded acts of cruelty and slaughter committed by Dutch troops during the period of warfare in Aceh.[25]

Hasan Mustafa (1852–1930) was a chief penghulu, or judge, for the colonial government and was stationed in Aceh. He had to balance traditional Muslim justice with Dutch law. To stop the Aceh rebellion, Hasan Mustafa issued a fatwa, telling the Muslims there in 1894, "It is Incumbent upon the Indonesian Muslims to be loyal to the Dutch East Indies Government".[26]

Japanese occupation

During World War II, Japanese troops occupied Aceh. The Acehnese ulama (Islamic clerics) fought against both the Dutch and the Japanese, revolting against the Dutch in February 1942 and against Japan in November 1942. The revolt was led by the All-Aceh Religious Scholars' Association (PUSA). The Japanese suffered 18 dead in the uprising while they slaughtered up to 100 or over 120 Acehnese.[27][28] The revolt happened in Bayu and was centered around Tjot Plieng village's religious school.[29][30][31][32] During the revolt, the Japanese troops armed with mortars and machine guns were charged by sword wielding Acehnese under Teungku Abduldjalil (Tengku Abdul Djalil) in Buloh Gampong Teungah and Tjot Plieng on 10 and 13 November.[33][34][35][36][37][38][39] In May 1945 the Acehnese rebelled again.[40] The religious ulama party gained ascendancy to replace district warlords (Ulèëbalang) party that formerly collaborated with the Dutch. Concrete bunkers still line the northernmost beaches.

Indonesian independence

After World War II, civil war erupted in 1945 between the district warlords party, that supported the return of a Dutch government, and the religious ulama party that supported the newly proclaimed state of Indonesia. The ulama won, and the area remained free during the Indonesian War of Independence. The Dutch military itself never attempted to invade Aceh. The civil war raised the religious ulama party leader, Daud Bereueh, to the position of military governor of Aceh.[41][42]

Acehnese rebellion

The Acehnese revolted soon after its inclusion into an independent Indonesia, a situation created by a complex mix of what the Acehnese regarded as transgressions against and betrayals of their rights.[43]

Sukarno, the first president of Indonesia, had reneged on his promise made on 16 June 1948 that Aceh would be allowed to rule itself in accordance with Islamic Law. Aceh was politically dismantled and incorporated into the province of North Sumatra in 1950. This resulted in the Acehnese Rebellion of 1953–59 which was led by Daud Beureu'eh who on 20 September 1953 declared a free independent Aceh under the leadership of Sekarmadji Maridjan Kartosoewirjo. In 1959, the Indonesian government attempted to placate the Acehnese by offering wide-ranging freedom in matters relating to religion, education and culture.[44][45]

Free Aceh Movement

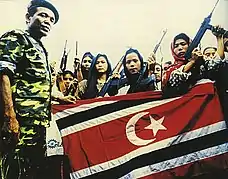

During the 1970s, under an agreement with the Indonesian central government, American oil and gas companies began exploitation of Aceh natural resources. Alleged unequal distribution of profits between central government and the native people of Aceh induced Dr. Hasan Muhammad di Tiro, former ambassador of Darul Islam,[41] to call for an independent Aceh. He proclaimed independence in 1976.

The movement had a small number of followers initially, and di Tiro himself had to live in exile in Sweden. Meanwhile, the province followed Suharto's policy of economic development and industrialization. During the late 1980s several security incidents prompted the Indonesian central government to take repressive measures and to send troops to Aceh. Human rights abuse was rampant for the next decade, resulting in many grievances on the part of the Acehnese toward the Indonesian central government. In 1990, the Indonesian government initiated military operations against GAM by deploying more than 12,000 Indonesian troops in the region.

During the late 1990s, chaos in Java and an ineffective central government gave an advantage to the Free Aceh Movement and resulted in the second phase of the rebellion, this time with large support from the Acehnese people. This support was demonstrated during the 1999 plebiscite in Banda Aceh which was attended by nearly half a million people (of four million population of the province). The Indonesian central government responded in 2001 by broadening Aceh's autonomy, giving its government the right to apply Sharia law more broadly and the right to receive direct foreign investment. This was again accompanied by repressive measures, however, and in 2003 an offensive began and a state of emergency was proclaimed in the province. The war was still ongoing when the tsunami disaster of 2004 struck the province.

In 2001, villagers from the North Aceh Regency sued Exxon Mobil for human rights abuses at the hands of Indonesian military units hired by the company for security for its natural gas operations. Exxon Mobil denies fault for the allegations. After a series of attacks against its operations, the company shut down its Arun natural gas operations in the province.[46]

Tsunami disaster

The western coastal areas of Aceh, including the cities of Banda Aceh, Calang, and Meulaboh, were among the areas hardest-hit by the tsunami resulting from the magnitude 9.2 Indian Ocean earthquake on 26 December 2004.[47] While estimates vary, over 170,000 people were killed by tsunami in Aceh and about 500,000 were left homeless. The tragedy of the tsunami was further compounded several months later, when the 2005 M8.6 Nias–Simeulue earthquake struck the sea bed between the islands of Simeulue Island in Aceh and Nias in North Sumatra. This second quake killed a further 1346 people on Nias and Simeulue, displaced tens of thousands more, and caused the tsunami response to be expanded to include Nias. the World Health Organisation estimates a 100% increase in prevalence of mild and moderate mental disorders in Aceh's general population after the tsunami.[48]

The population of Aceh before the December 2004 tsunami was 4,271,000 (2004). The population as of 15 September 2005 was 4,031,589, and at January 2014 was 4,731,705.[49] The 2020 census produced a total population of 5,274,871, comprising 2,647,563 males and 2,627,308 females.[50]

As of February 2006, more than a year after the tsunami, a large number of people were still living in barrack-style temporary living centers (TLC) or tents. Reconstruction was visible everywhere, but due to the sheer scale of the disaster, and logistic difficulties, progress was slow. A study in 2007 estimates 83.6% of the population has psychiatric illness, while 69.8% suffers from severe emotional distress.[51]

The ramifications of the tsunami went beyond the immediate impact to the lives and infrastructure of the Acehnese living on the coast. Since the disaster, the Acehnese rebel movement GAM, which had been fighting for independence against the Indonesian authorities for 29 years, has signed a peace deal (15 August 2005). The perception that the tsunami was punishment for insufficient piety in this proudly Muslim province is partly behind the increased emphasis on the importance of religion post-tsunami. This has been most obvious in the increased implementation of Sharia law, including the introduction of the controversial Wilayatul Hisbah or Syariah police. As homes are being built and people's basic needs are met, the people are also looking to improve the quality of education, increase tourism, and develop responsible, sustainable industry. Well-qualified educators are in high demand in Aceh.

While parts of the capital Banda Aceh were unscathed, the areas closest to the water, especially the areas of Kampung Jawa and Meuraxa, were completely destroyed. Most of the rest of the western coast of Aceh was severely damaged. Many towns completely disappeared. Other towns on Aceh's west coast hit by the disaster included Lhoknga, Leupung, Lamno, Patek, Calang, Teunom, and the island of Simeulue. Affected or destroyed towns on the region's north and east coasts were Pidie Regency, Samalanga, and Lhokseumawe.

The area was slowly rebuilt after the disaster. The government initially proposed the creation of a two-kilometer buffer zone along low-lying coastal areas within which permanent construction was not permitted. This proposal was unpopular among some local inhabitants and proved impractical in most situations, especially fishing families that are dependent on living near to the sea.

The Indonesian government set up a special agency for Aceh reconstruction, the Badan Rehabilitasi dan Rekonstruksi (BRR) headed by Kuntoro Mangkusubroto, a former Indonesian government minister. This agency had ministry level of authority and incorporated officials, professionals and community leaders from all backgrounds. Most of the reconstruction work was performed by local people using a mix of traditional methods and partial prefabricated structures, with funding coming from many international organizations and individuals, governments, and the people themselves.

The Government of Indonesia estimated in their Preliminary Damage and Losses Assessment[52] that damages amounted to US$4.5 billion (before inflation, and US$6.2 billion including inflation). Three years after the tsunami, reconstruction was still ongoing. The World Bank monitored funding for reconstruction in Aceh and reported that US$7.7 billion had been earmarked for the reconstruction whilst at June 2007 US$5.8 billion had been allocated to specific reconstruction projects, of which US$3.4 billion had actually been spent (58%).

In 2009, the government opened a US$5.6 million museum to commemorate the tsunami with photographs, stories, and a simulation of the earthquake that triggered the tsunami.[53]

Peace agreement and contemporary history

The 2004 tsunami helped trigger a peace agreement between the GAM and the Indonesian government. The mood in post-Suharto Indonesia in the liberal-democratic reform period, as well as changes in the Indonesian military, helped create an environment more favorable to peace talks. The roles of newly elected president Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and vice president Jusuf Kalla were highly significant.[54] At the same time, the GAM leadership was undergoing changes, and the Indonesian military had inflicted so much damage on the rebel movement that it had little choice but to negotiate with the central government.[55] The peace talks were first initiated by Juha Christensen, a Finnish peace activist, and then formally facilitated by a Finland-based NGO, the Crisis Management Initiative led by former Finnish president Martti Ahtisaari. The resulting peace agreement, generally known as the Helsinki MOU, was signed on 15 August 2005. Under the agreement Aceh would receive special autonomy and government troops would be withdrawn from the province in exchange for GAM's disarmament. As part of the agreement, the European Union dispatched 300 monitors. Their mission expired on 15 December 2006, following local elections.[56]

Aceh has been granted broader autonomy through Aceh government legislation covering special rights agreed upon in 2002 as well as the right of the Acehnese to establish local political parties to represent their interests.[57] Human rights advocates protested that previous human rights violations in the province needed to be addressed, however.[58][59]

Ecology and biodiversity

Aceh has the largest range of biodiversity in the Asian Pacific region.[60] Among the rarer large mammals are the Sumatran rhinoceros, Sumatran tiger, Orangutan and Sumatran elephant.[60] In 2014, there were 460 Sumatran elephants in Aceh including at least eight baby elephants.[61] The area has been suffering from deforestation since the 1970s.[62] The first wood pulp mill in Aceh was built in 1982.[63] The government of Aceh intends a law by which 1.2 million hectares would be opened for commercial use.[64] This proposal has caused many protests.[64]

Government

Within the country, Aceh is governed not as a province but as a special territory (daerah istimewa), an administrative designation intended to give the area increased autonomy from the central government in Jakarta. This has resulted in public caning for crimes deemed to have violated sharia law such as gambling, drinking, skipping Friday prayers, women wearing clothes deemed too tight, and most notably homosexuality.

Regional elections have been held in Aceh in recent years for senior positions at the provincial, regency (kabupaten) and district (kecamatan) levels. In the 2006 elections, Irwandi Yusuf was elected as the provincial governor for 2007–2012 and in elections in April 2012, Zaini Abdullah was elected as governor for 2012–2017.[65][66]

Law

Beginning with the promulgation of Law 44/1999, Aceh's governor began to issue limited Sharia-based regulations, for example requiring female government employees to wear Islamic dress. These regulations were not enforced by the provincial government, but as early as April 1999, reports emerged that groups of men in Aceh were engaging in vigilante violence in an effort to impose Sharia, for example, by conducting "jilbab raids," subjecting women who were not wearing Islamic headscarves to verbal abuse, cutting their hair or clothes, and committing other acts of violence against them.[67] The frequency of these and other attacks on individuals considered to be violating Sharia principles appeared to increase following the enactment of Law 44/1999 and the governor's Sharia regulations.[67] In 2014, a group of scholars who call themselves Tadzkiiratul Ummah, started to paint the pants of men and women as a call for heavier Islamic law enforcement in the area.[68]

Upon the enactment of the Special Autonomy Law in 2001, Aceh's provincial legislature enacted a series of qanuns (local laws) governing the implementation of Sharia. Five qanuns enacted between 2002 and 2004 contained criminal penalties for violations of Sharia: Qanun 11/2002 on "belief, ritual, and promoting Islam," which contains the Islamic attire requirement; Qanun 12/2003 prohibiting the consumption and sale of alcohol; Qanun 13/2003 prohibiting gambling; Qanun 14/2003 prohibiting "seclusion"; and Qanun 7/2004 on the payment of Islamic alms. With the exception of gambling, none of the offenses are prohibited outside of Aceh.[67]

Responsibility for enforcement of the qanuns rests both with the National Police and with a special Sharia police force unique to Aceh, known as the Wilayatul Hisbah (Sharia Authority). All of the qanuns provide for penalties including fines, imprisonment, and caning, the latter a punishment unknown in most parts of Indonesia. Between mid-2005 and early 2007, at least 135 people were caned in Aceh for transgressing the qanuns.[67] In April 2016, a 60-year-old non-Muslim woman was sentenced to 30 lashes for selling alcohol drinks. The controversy is that qanun is not allowed for non-Muslim person, and national law should be used instead as in other parts of Indonesia.[69]

In April 2009, Partai Aceh won control of the local parliament in Aceh's first post-war legislative elections. In September 2009, one month before the new legislators were to take office, the outgoing parliament unanimously endorsed two new qanuns to expand the existing criminal Sharia framework in Aceh.

- One bill, the Qanun on Criminal Procedure (Qanun Hukum Jinayat), to create an entirely new procedural code for the enforcement of Sharia by police, prosecutors, and courts in Aceh.[67]

- The other bill, the Qanun on Criminal Law (Qanun Jinayat), reiterated the existing criminal Sharia prohibitions, at times enhancing their penalties, and a host of new criminal offenses, including ikhtilat (intimacy or mixing), zina (adultery, defined as willing intercourse by unmarried people), sexual harassment, rape, and homosexual conduct.[70] The law authorized punishments including up to 60 lashes for "intimacy," up to 100 lashes for engaging in homosexual conduct, up to 100 lashes for adultery by unmarried persons, and death by stoning for adultery by a married person.[67]

Caning

In practice since the introduction of the new laws, there has been a considerable increase in the use of the penalties provided set out in the laws. As an example, in August 2015 six men in Bireun regency were arrested and caned for betting on the names of passing buses.[71] And it was reported that on just one day, 18 September 2015, a total of 34 people were caned in Banda Aceh and in the nearby regency of Aceh Besar.[72]

Two gay men are to be publicly lashed 85 times each under sharia law after being filmed by vigilantes in Indonesia. An Islamic court in the province of Aceh passed down its first sentence for homosexuality on the International Day Against Homophobia and Transphobia, 17 May 2017 in spite of international appeals to spare the couple.[73]

Public whipping is the common hudud punishment for gambling, adultery, drinking alcohol, and having gay or pre-marital sex. Typically the whipping has been done by men. In 2020, with increased enforcement and more crimes being conducted by women, Aceh authorities say they are trying to follow Islamic law, which calls for women to whip female perpetrators.[74][75]

Administrative divisions

Administratively, the province now is subdivided into eighteen regencies (kabupaten) and five autonomous cities (kota). The capital and the largest city is Banda Aceh, located on the coast near the northern tip of Sumatra. When originally devised, the province comprised the city of Banda Aceh and seven regencies – Aceh Besar, Pidie, North Aceh, East Aceh, Central Aceh, West Aceh and South Aceh; Sabang City was separated from Aceh Besar in 1967 and Southeast Aceh Regency from Central Aceh in 1974; three additional regencies were formed in 1999 – Aceh Singkil, Bireuen and Simeulue; the cities of Lhokseumawe and Langsa were given separate status in 2001 and five additional regencies created in 2002 – Aceh Jaya, Aceh Tamiang, Gayo Kues, Nagan Raya and Southwest Aceh in 2002. Bener Meriah Regency was created in 2003, and Pidie Jaya Regency and Subulussalam City in 2007. Some local areas are pushing to create new autonomous areas, usually with the stated goal of enhancing local control over politics and development.

The cities and regencies (subdivided into the 289 districts or kecamatan of Aceh), are listed below with their populations at the 2010 census[76] and the 2020 census,[50] together with the officially estimated population as at mid 2021.[77]

| Name | Capital | Est. | Establish by statute | Area (in km2) | Population 2010 census | Population 2020 census | Population mid 2021 estimate | HDI[78] 2021 estimates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sabang City | 1967 | 153.00 | 30,653 | 41,197 | 42,070 | 0.761 (High) | ||

| Aceh Besar Regency | Jantho | 1956 | UU 24/1956 | 2,969.00 | 351,418 | 405,535 | 409,530 | 0.735 (High) |

| Banda Aceh City | 1956 | UU 24/1956 | 61.36 | 223,446 | 252,899 | 255,030 | 0.857 (Very High) | |

| Aceh Jaya Regency | Calang | 2002 | UU 4/2002 | 3,812.99 | 76,782 | 93,159 | 94,418 | 0.698 (Medium) |

| Pidie Regency | Sigli | 1956 | UU 24/1956 | 3,086.95 | 379,108 | 435,280 | 439,400 | 0.707 (High) |

| Pidie Jaya Regency | Meureudu | 2007 | UU 7/2007 | 1,073.60 | 132,956 | 158,400 | 160,330 | 0.736 (High) |

| Bireuen Regency | Bireuen | 1999 | UU 48/1999 | 1,901.20 | 389,288 | 436,420 | 439,790 | 0.723 (High) |

| North Aceh Regency (Aceh Utara) | Lhoksukon | 1956 | UU 24/1956 | 3,236.86 | 529,751 | 602,793 | 608,106 | 0.694 (Medium) |

| Lhokseumawe City | 2001 | UU 2/2001 | 181.06 | 171,163 | 188,713 | 189,940 | 0.775 (High) | |

| East Aceh Regency (Aceh Timur) | Idi Rayeuk | 1956 | UU 24/1956 | 6,286.01 | 360,475 | 422,401 | 427,030 | 0.678 (Medium) |

| Langsa City | 2001 | UU 3/2001 | 262.41 | 148,945 | 185,971 | 188,880 | 0.774 (High) | |

| Aceh Tamiang Regency | Karang Baru | 2002 | UU 4/2002 | 1,956.72 | 251,914 | 294,356 | 297,520 | 0.694 (Medium) |

| Gayo Lues Regency | Blangkejeren | 2002 | UU 4/2002 | 5,719.58 | 79,560 | 99,532 | 101,100 | 0.675 (Medium) |

| Bener Meriah Regency | Simpang Tiga Redelong | 2003 | UU 41/2003 | 1,454.09 | 122,277 | 161,342 | 164,520 | 0.732 (High) |

| Central Aceh Regency (Aceh Tengah) | Takengon | 1956 | UU 24/1956 | 4,318.39 | 175,527 | 215,860 | 218,680 | 0.733 (High) |

| West Aceh Regency (Aceh Barat) | Meulaboh | 1956 | UU 24/1956 | 2,927.95 | 173,558 | 198,736 | 200,579 | 0.716 (High) |

| Nagan Raya Regency | Suka Makmue | 2002 | UU 4/2002 | 3,363.72 | 139,663 | 168,392 | 170,591 | 0.693 (Medium) |

| Southwest Aceh Regency (Aceh Barat Daya) | Blangpidie | 2002 | UU 4/2002 | 1,490.60 | 126,036 | 150,780 | 152,660 | 0.669 (Medium) |

| South Aceh Regency (Aceh Selatan) | Tapaktuan | 1956 | UU 24/1956 | 3,841.60 | 202,251 | 232,410 | 234,630 | 0.674 (Medium) |

| Southeast Aceh Regency (Aceh Tenggara) | Kutacane | 1974 | UU 7/1974 | 4,231.43 | 179,010 | 220,860 | 224,119 | 0.694 (Medium) |

| Subulussalam City | 2007 | UU 8/2007 | 1,391.00 | 67,446 | 90,751 | 92,671 | 0.652 (Medium) | |

| Aceh Singkil Regency (including the Banyak Islands) | Singkil | 1999 | UU 14/1999 | 2,185.00 | 102,509 | 126,514 | 128,384 | 0.692 (Medium) |

| Simeulue Regency | Sinabang | 1999 | UU 48/1999 | 2,051.48 | 80,674 | 92,865 | 93,762 | 0.664 (Medium) |

Economy

In 2006, the economy of Aceh grew by 7.7% after having minimal growth since the devastating tsunami.[79] This growth was primarily driven by the reconstruction effort with massive growth in the building/construction sector.

The ending of the conflict, and the reconstruction program resulted in the structure of the economy changing significantly since 2003. Service sectors played a more dominant role whilst the share of the oil and gas sectors continued to decline.

| Sector (% share of Aceh GDP) | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture and fisheries | 17 | 20 | 21 | 21 |

| Oil, gas and mining | 36 | 30 | 26 | 25 |

| Manufacturing (incl. oil and gas manufacturing) | 20 | 18 | 16 | 14 |

| Electricity and water supply | ... | |||

| Building / construction | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| Trade, hotels and restaurants | 11 | 12 | 14 | 15 |

| Transport & communication | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Banking & other financial | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Services | 8 | 10 | 13 | 13 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

After peaking at around 40% in December 2005, largely as a result of the Dutch disease impact of sudden aid flows into the province, inflation declined steadily and was 8.5% in June 2007, close to the national level in Indonesia of 5.7%. Persistent inflation means that Aceh's consumer price index (CPI) remains the highest in Indonesia. As a result, Aceh's cost competitiveness has declined as reflected in both inflation and wage data. Although inflation has slowed down, CPI has registered steady increases since the tsunami. Using 2002 as a base, Aceh's CPI increased to 185.6 (June 2007) while the national CPI increased to 148.2. There have been relatively large nominal wage increases in particular sectors, such as construction where, on average, workers' nominal wages have risen to almost Rp.60,000 per day, from Rp.29,000 pre-tsunami. This is also reflected in Aceh's minimum regional wage (UMR, or Upah Minimum Regional), which increased by 55% from Rp.550,000 pre-tsunami to Rp.850,000 in 2007, compared with an increase of 42% in neighboring North Sumatra, from Rp.537,000 to Rp.761,000.

Poverty levels increased slightly in Aceh in 2005 after the tsunami, but by less than expected.[80] The poverty level then fell in 2006 to below the pre-tsunami level, suggesting that the rise in tsunami-related poverty was short lived and reconstruction activities and the end of the conflict most probably facilitated this decline. However, poverty in Aceh remains significantly higher than in the rest of Indonesia.[81] A large number of the Acehnese remain vulnerable to poverty, reinforcing the need for further sustained efforts at development in the post-tsunami construction period.[82]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 2,008,595 | — |

| 1980 | 2,611,271 | +2.96% |

| 1990 | 3,416,156 | +2.72% |

| 1995 | 3,847,583 | +2.41% |

| 2000 | 3,930,905 | +0.43% |

| 2010 | 4,494,410 | +1.35% |

| 2015 | 4,993,385 | +2.13% |

| 2020 | 5,274,871 | +1.10% |

| 2021 | 5,333,733 | +1.12% |

| Source: Badan Pusat Statistik 2022. | ||

The population of Aceh was not adequately documented during the Indonesia 2000 census because the insurgency complicated the process of collecting accurate information. An estimated 170,000 people died in Aceh in the 2004 tsunami which further complicates the task of careful demographic analysis. According to the most recent censuses, the total population of Aceh in 2010 was 4,486,570, in 2015 was 4,993,385, and in 2020 was 5,274,871.[83] The official estimate for mid 2021 is 5,333,733.[84]

Ethnic and cultural groups

Aceh is a diverse region occupied by several ethnic and language groups. The major ethnic groups are the Acehnese (who are distributed throughout Aceh), Gayo (in central and eastern part), Alas (in Southeast Aceh Regency), Tamiang-Malays (in Aceh Tamiang Regency), Aneuk Jamee (descendant from Minangkabau, concentrated in southern and southwestern), Kluet (in South Aceh Regency), Singkil (in Singkil and Subulussalam), Simeulue and Sigulai (on Simeulue Island). There is also a significant population of Chinese, Among the present day Acehnese can be found some individuals of Arab, Turkish, and Indian descent.

The Acehnese language is widely spoken within the Acehnese population. This is a member of the Aceh-Chamic group of languages, whose other representatives are mostly found in Vietnam and Cambodia, and is also closely related to the Malay group of languages. Acehnese also has many words borrowed from Malay and Arabic and traditionally was written using Arabic script. Acehnese is also used as local language in Langkat and Asahan (North Sumatra), and Kedah (Malaysia), and once dominated Penang. Alas and Kluet are closely related languages within the Batak group. The Jamee language originated from Minangkabau language in West Sumatra, with just a few variations and differences.

Religion

Religion in Aceh[85]

According to 2010 census of the Central Statistics Agency, Muslims dominate Aceh with more than 98% or 4,413,200 followers and only 50,300 Protestants and 3,310 Catholics.[86] Religious issues are often sensitive in Aceh. There is very strong support for Islam across the province, and sometimes other religious groups – such as Christians or Buddhists – feel that they are subject to social or community pressure to limit their activities. The official explanation for this action, supported by both the governor of Aceh Zaini Abdullah and the Indonesian home affairs minister Gamawan Fauzi from Jakarta, was that the churches did not have the appropriate permits. Earlier in April 2012, a number of churches in the Singkil regency in southern Aceh had also been ordered to close.[87] In response, some Christians voiced concern about these actions. In 2015 a church was burned down and another attacked in which a Muslim rioter was shot, causing President Joko Widodo to call for calm.[88]

Human rights

Caning has increasingly been used as a form of judicial punishment in Aceh.[89] This is backed by the governor of Aceh. At least 72 people were caned for various offences, including drinking alcohol, being alone with someone of the opposite sex who was not a marriage partner or relative (khalwat), gambling and for being caught having gay sex.[90] The Acehnese authorities passed a series of by-laws governing the implementation of Sharia after the enactment of the province's Special Autonomy Law in 2001. In 2016 alone, 339 public caning cases were documented by human rights organizations.[91]

In January 2018, the Aceh police, with support from the Aceh autonomous government, raided hair salons known to have LGBT clients and staff as part of an operasi penyakit masyarakat ("community sickness operation"). The police abused all LGBT citizens within the premises of the parlors and arrested twelve transgender women. The arrested trans women were stripped topless, had their heads shaved, and were forced to chant insults at themselves as part of a process "until they really become men". The intent of the incident was to reverse what officials deemed a "social disease" and that parents were coming to them upset at the increasing number of LGBT individuals in Aceh.[92][93] The event was decried by human rights organizations local and worldwide, such as Amnesty International. Usman Hamid stated for the Indonesia branch of the organization that "cutting the hair of those arrested to 'make them masculine' and forcing them to dress like men are forms of public shaming and amount to cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment, in contravention of Indonesia's international obligations".[94]

Traditional culture

Aceh has a variety of distinctive arts and culture.

Traditional weapon

- Rencong is a type of dagger, a traditional weapon of the Acehnese people. The shape resembles the letter L, and when viewed more closely the form is bismillah calligraphy.

In addition to rencong, the Acehnese people also possessed several other special weapons, such as sikin panyang, peurise awe, peurise teumaga, siwah, geuliwang and peudeueng.[95]

Traditional house

Aceh's traditional house is called Rumoh Aceh. This house is a type of house on stilts with three main parts and one additional section. The three main parts of the Aceh house are the seuramoë keuë (front porch), seuramoë teungoh (middle porch) and seuramoë likôt (back porch). Another additional part is the rumoh dapu (kitchen house).[96]

Dance

Traditional Acehnese dances illustrate traditional heritage, religion, and local folklore. Acehnese dances are generally performed in groups, in which a group of dancers are of the same sex, and there are standing or sitting positions. When viewed from the accompanying music, the dances can be grouped into two types; namely accompanied by the vocal and percussion of the dancer's own body, and accompanied by an ensemble of musical instruments. Some dances that are famous at the national and even world level are dances originating from Aceh, such as the Rateb Meuseukat Dance and the Saman dance.[97]

Food

Acehnese cuisine uses combinations of spices found in Indian and Arabic cuisine, include ginger, pepper, coriander, cumin, cloves, cinnamon, cardamom, and fennel. A variety of Acehnese foods are cooked with curry or curry spices and coconut milk, which are generally combined with meat, such as buffalo meat, beef, lamb, fish and chicken. Certain recipes have traditionally used cannabis as a seasoning; which is also found in some other Southeast Asian dishes such as in Laos, but now the material is no longer used. Dishes native to Aceh include nasi gurih, mie aceh, mi caluk and timphan.

Literature

The oldest Acehnese manuscripts that can be found are from 1069 H (1658/1659 AD), namely Hikayat Seuma'un.

Before Dutch colonialism (1873–1942), almost all Acehnese literature was in the form of poetry known as Hikayat. Very little is in the form of prose and one of them is the Book of Bakeu Meunan which is a translation of the book Qawaa'id al-Islaam.

It was only after the arrival of the Dutch that Acehnese writings appeared in the form of prose, in the 1930s, such as Lhee Saboh Nang written by Aboe Bakar and De Vries. It was only afterward that various forms of prose appeared, but still remained dominated by the form of Hikayat.[98]

See also

- List of people from Aceh

Notes

- (in Indonesian) – via Wikisource.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2022.

- "Arti "Orang Aceh" Dalam UUPA Menurut KIP Subulussalam". 23 December 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2022.

- Aris Ananta; Evi Nurvidya Arifin; M. Sairi Hasbullah; Nur Budi Handayani; dan Agus Pramono (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies dan BPS – Statistics Indonesia.

- "How An Escape Artist Became Aceh's Governor" Archived 3 August 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Time, 15 February 2007

- United Nations. Economic and Social Survey of Asia and the Pacific 2005. 2005, page 172

- "Direktorat Jenderal Perimbangan Keuangan | Perubahan Sebutan Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam menjadi Aceh". www.djpk.kemenkeu.go.id (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 31 August 2018. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- Daniel Perret (24 February 2007). "Aceh as a Field for Ancient History Studies" (PDF). Asia Research Institute-National University of Singapore. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 January 2008. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- Abuza, Zachary (2016). Forging Peace in Southeast Asia: Insurgencies, Peace Processes, and Reconciliation. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-4422-5757-3.

- Reid, Anthony (2005). An Indonesian Frontier: Acehnese and Other Histories of Sumatra. NUS Press. p. 96. ISBN 978-9971-69-298-8.

- Marco Polo, Sir Henry Yule, Henri Cordier (January 1993). The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition (New ed of 1903 ed.). Dover Publications Inc. p. 299. ISBN 978-0486275871.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- "Changing a Hindu temple into the Indrapuri Mosque in Aceh: the beginning of Islamisation in Indonesia – a vernacular architectural context" (PDF).

Kompas argues that Indrapuri Mosque in Aceh was built in the 10th century AD by the Lamuri kingdom. At the time, it functioned as the Temple of Hinduism [4]. In addition, Zein says that the function of the temple was changed into a Mosque when the King and the people of Lamuri Hindu kingdom converted to Islam in 1205 AD

- "Indra Patra Fortress". Indonesia Tourism.

- Reid (1988 and 1993)

- Ricklefs (1991), page 4

- Skutsch, Carl, ed. (2005). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge. p. 5. ISBN 1-57958-468-3.

- Ricklefs (1991), page 7

- Ricklefs (1991), page 17

-

- D. G. E. Hall, A History of South-east Asia. London: Macmillan, 1955.

- Ricklefs, M.C. (2001) A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1200. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p 185–188.

- Nicholas Tarling, ed. (1992). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: Volume 2, the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. Cambridge U.P. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-521-35506-3. Archived from the original on 23 April 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- E.H. Kossmann, The Low Countries 1780–1940 (1978) pp 400–401

- Linawati Sidarto, "Images of a grisly past", The Jakarta Post: Weekender, July 2011 "Grisly Images | the Jakarta Post". Archived from the original on 27 June 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- Mufti Ali, "A Study of Hasan Mustafa's 'Fatwa: 'It Is Incumbent upon the Indonesian Muslims to be Loyal to the Dutch East Indies Government,'" Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society, April 2004, Vol. 52 Issue 2, pp 91–122

- John Martinkus (2004). Indonesia's Secret War in Aceh. Random House Australia. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-74051-209-1. Archived from the original on 3 June 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Merle Calvin Ricklefs (2001). A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1200. Stanford University Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-8047-4480-5. Archived from the original on 30 July 2019. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Tempo. 43–52. Vol. 3. Arsa Raya Perdana. 2003. p. 27. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- atjehcyberID. "Sejarah Jejak Perlawanan Aceh". Atjeh Cyber Warrior. Archived from the original on 27 April 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "Waspada, Sabtu 17 Maret 2012". Issuu. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "Waspada, Sabtu 17 Maret 2012". Issuu. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- Berita Kadjian Sumatera: Sumatra Research Bulletin. Vol. 1–4. Dewan Penjelidikan Sumatera. 1971. p. 35. Archived from the original on 12 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Abdul Haris Nasution (1963). Tentara Nasional Indonesia. Ganaco. p. 89. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Sedjarah Iahirnja Tentara Nasional Indonesia. Sedjarah Militer Dam II/BB. 1970. p. 12. Archived from the original on 29 April 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Indonesia. Panitia Penjusun Naskah Buku "20 Tahun Indonesia Merdeka."; Indonesia (1966). 20 [i. e Dua puluh] tahun Indonesia merdeka. Vol. 7. Departement Penerangan. p. 547. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Indonesia. Angkatan Darat. Pusat Sedjarah Militer (1965). Sedjarah TNI-Angkatan Darat, 1945–1965. [Tjet. 1.]. PUSSEMAD. p. 8. Archived from the original on 18 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Indonesia. Departemen Penerangan (1965). 20 tahun Indonesia merdeka. Vol. 7. Departemen Penerangan R.I. p. 545. Archived from the original on 29 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- Atjeh Post, Minggu Ke III September 1990. halaman I & Atjeh Post, Minggu Ke IV September 1990 halaman I

- Louis Jong (2002). The collapse of a colonial society: the Dutch in Indonesia during the Second World War. KITLV Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-90-6718-203-4. Archived from the original on 8 May 2016. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

-

- M Nur El-Ibrahimy, Peranan Teungku M. Daud Bereueh dalam Pergolakan di Aceh, 2001.

-

- A.H. Nasution, Seputar Perang Kemerdekaan Indonesia, Jilid II, 1977

- "Moraref". moraref.kemenag.go.id. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Apipudin, Apipudin (2016). "Daud Beureu'eh and The Darul Islam Rebellion in Aceh". Buletin Al-Turas. 22 (1): 145–167. doi:10.15408/bat.v22i1.7221. ISSN 2579-5848. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Drexler, Elizabeth F. (6 April 2009). Aceh, Indonesia: Securing the Insecure State. University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 978-0-8122-2071-1. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- Banerjee, Neela (21 June 2001). "Lawsuit Says Exxon Aided Rights Abuses". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2 June 2020. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- For details of the impact of the tsunami in Aceh, see Jayasuriya, Sisira and Peter McCawley in collaboration with Bhanupong Nidhiprabha, Budy P. Resosudarmo and Dushni Weerakoon, The Asian Tsunami: Aid and Reconstruction after a Disaster Archived 16 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Cheltenham UK and Northampton MA USA: Edward Elgar and Asian Development Bank Institute, 2010.

- Wise, Cat (2011). "Tsunami-Devastated Aceh, an Epicenter of Mental Health Woes". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on 10 April 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2014.

- "Estimasi Penduduk Menurut Umur Tunggal Dan Jenis Kelamin 2014 Kementerian Kesehatan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2021.

- Souza, R., Bernatsky, S., Ryes, R., Jong, K. (2007). "Mental Health Status of Vulnerable Tsunami-Affected Communities: A Survey in Aceh Province, Indonesia". Journal of Traumatic Stress. 20(3), 263–269

- Stefan G. Koeberle. "Preliminary Damage and Losses Assessment on". Web.worldbank.org. Archived from the original on 4 September 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- "Indonesia Opens Tsunami Museum". The Irrawaddy. March–April 2009. p. 3.

- A very useful and detailed account of the negotiation process from the Indonesian side is in the book by the Indonesian key negotiator, Hamid Awaludin, Peace in Aceh: Notes on the peace process between the Republic of Indonesia and the Aceh Freedom Movement (GAM) in Helsinki, translated by Tim Scott, 2009, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Jakarta. ISBN 978-979-1295-11-6.

- "A happy, peaceful anniversary in Aceh". Asia Times. 15 August 2006. Archived from the original on 3 February 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "The Helsinki Agreement: A More Promising Basis for Peace in Aceh?". East-West Center. 15 December 2005. Archived from the original on 8 November 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Hillman, Ben (2012). "'Power Sharing and Political Party Engineering in Conflict-Prone Societies: The Indonesian Experiment in Aceh". Conflict Security and Development. 12 (2): 149–169. doi:10.1080/14678802.2012.688291. S2CID 154463777.

- Veena Siddharth, Asia advocacy director (27 August 2005). "Next steps for Aceh after the peace pact | Human Rights Watch". Hrw.org. Archived from the original on 15 August 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- "Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the Republic of Indonesia and the Free Aceh Movement" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 September 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Simanjuntak, Hotli; Sangaji, Ruslan (20 May 2013). "Scientists urged to stand up for Aceh's biodiversity". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- "Gajah Sumatera Hanya Tersisa 460 Ekor di Aceh". 19 August 2014. Archived from the original on 21 August 2014. Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- McGregor, Andrew (2010). "Green and REDD? Towards a Political Ecology of Deforestation in Aceh, Indonesia". Human Geography. 3 (2): 21–34. doi:10.1177/194277861000300202. S2CID 132046525.

- "Aceh: ecological war zone". Down to Earth (47). 2000. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012.

- The Jakarta Post. "Global calls to save Aceh forest". The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "Priorities for a GAM-Led Government in Aceh". Crisis Group. 29 December 2006. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- Iis*, Em Yusuf; Yunus, Mukhlis; Adam, Muhammad; Sofyan, Hizir (2018). "Antecedent Model of Empowerment and Performance of Aceh Government With Motivation as the Intervening Variable". The Journal of Social Sciences Research: 743–747:2. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 9 January 2020.

- "Policing Morality Abuses in the Application of Sharia in Aceh, Indonesia". Human Rights Watch. 2010. pp. 13–17. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- Edi Sumardi (4 December 2014). "Ini Hukuman Bagi Wanita Berpakaian Ketat, Celananya Disemprot Cat". Archived from the original on 8 December 2014. Retrieved 4 December 2014.

- Rachmadin Ismail (14 April 2016). "Hukuman Cambuk Pertama Terhadap Non Muslim di Aceh Jadi Sorotan". Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- Hotli Simanjuntak and Ina Parlina, 'Aceh fully enforces Sharia' Archived 7 March 2018 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Post, 7 February 2014.

- 'Six men caned for betting on passing buses in Aceh' Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Post, 27 August 2015.

- Hotli Simanjuntak, 'Dozens of sharia vilators caned in Aceh' Archived 28 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Post, 19 September 2015.

- Lizzie Dearden (17 May 2017). "Sharia court in Indonesia sentences two gay men to 85 lashes each after being caught having sex". Independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 1 September 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2017.

- "Indonesia's Aceh unveils new female flogging squad". The Gulf News. 28 January 2020. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- "Indonesia's Aceh unveils female flogging squad as more women run afoul of Islamic law". The Japan Times. 31 January 2020. Archived from the original on 25 March 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Biro Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2011.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2022.

- "Indeks-Pembangunan-Manusia-2021". Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- World Bank, Jakarta, Aceh Economic Update November 2007. Archived 28 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- World Bank, Jakarta, Aceh Poverty Assessment 2008 Archived 28 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- A useful survey of the state of development up to 2010 is in the UNDP Provincial Human Development Report Aceh 2010 Archived 28 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine.

- Edward Aspinall, Ben Hillman, and Peter McCawley, Governance and capacity-building in post-crisis Aceh' Archived 29 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine, a report by Australian National University Enterprise, Canberra, for UNDP, Jakarta, 2012.

- Badan Pusat Statistik 2021.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2022.

- "Visualisasi Data Kependuduakan – Kementerian Dalam Negeri 2020". www.dukcapil.kemendagri.go.id. Archived from the original on 5 August 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- "Regent orders churches closed, destroyed in Aceh". Archived from the original on 17 June 2012. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Bagus BT Saragih, 'Closed churches lack permits: Gamawan' Archived 26 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, The Jakarta Pose, 25 October 2012.

- "Jokowi calls for calm amid clashes in Aceh". Channel NewsAsia. 14 October 2015. Archived from the original on 15 October 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- Indonesian man flogged after breaking adultery law he helped draw up Archived 1 November 2019 at the Wayback Machine The Guardian, 2019

- "Indonesian men caned for gay sex in Aceh". BBC News. 23 May 2017. Archived from the original on 30 October 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2018.

- "Two Indonesians sentenced to 85 lashes of cane for gay sex". Reuters. 17 May 2017. Archived from the original on 10 August 2021. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- Indonesian, B. B. C. (2018). "Indonesia police cut trans women's hair". BBC News. Archived from the original on 6 April 2019. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- "Police arrest 12 trans women and shave their heads 'to make them men'". PinkNews. Archived from the original on 16 August 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- "Rights groups decry 'shaming' of transgender people in Indonesia's..." Reuters. 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 24 November 2018. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- Pratiwy, Devi (August 2019). "Cultural Norms and Values Configuration in Acehnese Traditional Fishing Ritual | KnE Social Sciences". Kne Social Sciences: 189–198–189–198. doi:10.18502/kss.v3i19.4846. S2CID 201382724. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- Graf, Arndt; Schroter, Susanne; Wieringa, Edwin (2010). Aceh: History, Politics and Culture. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4279-12-3. Archived from the original on 1 April 2022. Retrieved 24 October 2020.

- Fadillah, Dani; Nuryana, Zalik; Sahuddin, Muhammad; Hao, Dong (19 December 2019). "International-Cultural Communication of the Saman Dance Performance by Indonesian Students in Nanjing". International Journal of Visual and Performing Arts. 1 (2): 98–105. doi:10.31763/viperarts.v1i2.70. ISSN 2684-9259. Archived from the original on 17 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- "Aceh: History, Politics and Culture". bookshop.iseas.edu.sg. Archived from the original on 24 October 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

References

- Indonesia. Angkatan Darat. Pusat Sedjarah Militer (1965). Sedjarah TNI-Angkatan Darat, 1945–1965. [Tjet. 1.]. PUSSEMAD. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Indonesia. Panitia Penjusun Naskah Buku "20 Tahun Indonesia Merdeka.", Indonesia (1966). 20 [i. e Dua puluh] tahun Indonesia merdeka, Volume 7. Departement Penerangan. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Indonesia. Departemen Penerangan (1965). 20 tahun Indonesia merdeka, Volume 7. Departemen Penerangan R.I. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Jong, Louis (2002). The collapse of a colonial society: the Dutch in Indonesia during the Second World War. Vol. 206 of Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Nederlands Geologisch Mijnbouwkundig Genootschap, Volume 206 of Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (illustrated ed.). KITLV Press. ISBN 978-90-6718-203-4. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Martinkus, John (2004). Indonesia's Secret War in Aceh (illustrated ed.). Random House Australia. ISBN 978-1-74051-209-1. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Abdul Haris Nasution (1963). Tentara Nasional Indonesia, Volume 1. Ganaco. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (2001). A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1200 (illustrated ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-4480-5. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Tempo: Indonesia's Weekly News Magazine, Volume 3, Issues 43–52. Arsa Raya Perdana. 2003. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- Berita Kadjian Sumatera: Sumatra Research Bulletin, Volumes 1–4. Contributors Sumatra Research Council (Hull, England), University of Hull Centre for South-East Asian Studies. Dewan Penjelidikan Sumatera. 1971. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Sedjarah Iahirnja Tentara Nasional Indonesia. Contributor Indonesia. Angkatan Darat. Komando Daerah Militer II Bukit Barisan. Sejarah Militer. Sedjarah Militer Dam II/BB. 1970. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)

Further reading

- Bowen, J. R. (1991). Sumatran politics and poetics : Gayo history, 1900–1989. New Haven, Yale University Press.

- Bowen, J. R. (2003). Islam, Law, and Equality in Indonesia Cambridge University Press

- Iwabuchi, A. (1994). The people of the Alas Valley : a study of an ethnic group of Northern Sumatra. Oxford, England; New York, Clarendon Press.

- McCarthy, J. F. (2006). The Fourth Circle. A Political Ecology of Sumatra's Rainforest Frontier, Stanford University Press.

- Miller, Michelle Ann. (2009). Rebellion and Reform in Indonesia. Jakarta's Security and Autonomy Policies in Aceh. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-45467-4

- Miller, Michelle Ann, ed. (2012). Autonomy and Armed Separatism in South and Southeast Asia (Singapore: ISEAS).

- Siegel, James T. 2000. The rope of God. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08682-0; A classic ethnographic and historical study of Aceh, and Islam in the region. Originally published in 1969

External links

- Official website

(in Indonesian)

(in Indonesian) - Local App Portal (in Indonesian)