Mount Erebus disaster

The Mount Erebus disaster occurred on 28 November 1979 when Air New Zealand Flight 901 (TE-901)[nb 1] flew into Mount Erebus on Ross Island, Antarctica, killing all 237 passengers and 20 crew on board.[1][2] Air New Zealand had been operating scheduled Antarctic sightseeing flights since 1977. This flight was supposed to leave Auckland Airport in the morning and spend a few hours flying over the Antarctic continent, before returning to Auckland in the evening via Christchurch.

Debris from the DC-10's fuselage photographed in 2004: Most of the wreckage of Flight 901 remains at the accident site. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 28 November 1979 |

| Summary | Controlled flight into terrain |

| Site | Mount Erebus, Antarctica 77°25′30″S 167°27′30″E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 |

| Operator | Air New Zealand |

| Call sign | NEW ZEALAND 901 |

| Registration | ZK-NZP |

| Flight origin | Auckland International Airport |

| 1st stopover | Non-stop flight over Antarctica |

| Last stopover | Christchurch International Airport |

| Destination | Auckland International Airport |

| Occupants | 257 |

| Passengers | 237 |

| Crew | 20 |

| Fatalities | 257 |

| Survivors | 0 |

The initial investigation concluded the accident was caused primarily by pilot error, but public outcry led to the establishment of a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the crash. The commission, presided over by Justice Peter Mahon QC, concluded that the accident was primarily caused by a correction made to the coordinates of the flight path the night before the disaster, coupled with a failure to inform the flight crew of the change, with the result that the aircraft, instead of being directed by computer down McMurdo Sound (as the crew had been led to believe), was instead rerouted to a path toward Mount Erebus. Justice Mahon's report accused Air New Zealand of presenting "an orchestrated litany of lies", and this led to changes in senior management at the airline. The Privy Council later ruled that the finding of a conspiracy was a breach of natural justice and not supported by the evidence.

The accident is the deadliest accident in the history of Air New Zealand and one of New Zealand's deadliest peacetime disasters.

Flight and aircraft

The flight was designed and marketed as a unique sightseeing experience, carrying an experienced Antarctic guide, who pointed out scenic features and landmarks using the aircraft public-address system, while passengers enjoyed a low-flying sweep of McMurdo Sound.[3] The flights left and returned to New Zealand the same day.

Flight 901 would leave Auckland International Airport at 8:00 am for Antarctica, and arrive back at Christchurch International Airport at 7:00 pm after flying 5,360 miles (8,630 km). The aircraft would make a 45-minute stop at Christchurch for refuelling and crew change, before flying the remaining 464 miles (747 km) to Auckland, arriving at 9:00 pm. Tickets for the November 1979 flights cost NZ$359 per person (equivalent to $2,977 in March 2022).[4][5]

Dignitaries including Sir Edmund Hillary had acted as guides on previous flights. Hillary was scheduled to act as the guide for the fatal flight of 28 November 1979, but had to cancel owing to other commitments. His long-time friend and climbing companion, Peter Mulgrew, stood in as guide.[6]

The flights usually operated at about 85% of capacity; the empty seats, usually the ones in the centre row, allowed passengers to move more easily about the cabin to look out of the windows.

The aircraft used on the Antarctic flights were Air New Zealand's eight McDonnell Douglas DC-10-30 trijets. The aircraft on 28 November was registered ZK-NZP. The 182nd DC-10 to be built, and the fourth DC-10 to be introduced by Air New Zealand, ZK-NZP was handed over to the airline on 12 December 1974 at McDonnell Douglas's Long Beach plant. It had logged more than 20,700 flight hours prior to the crash.[1][7]

Accident

Circumstances surrounding the accident

Captain Jim Collins (45) and co-pilot Greg Cassin (37) had never flown to Antarctica before (while flight engineer Gordon Brooks had flown to Antarctica only once previously), but they were experienced pilots and were considered qualified for the flight. On 9 November 1979, 19 days before departure, the two pilots attended a briefing in which they were given a copy of the previous flight's flight plan.[3]

The flight plan that had been approved in 1977 by the Civil Aviation Division of the New Zealand Department of Transport was along a track directly from Cape Hallett to the McMurdo non-directional beacon (NDB), which, coincidentally, entailed flying almost directly over the 12,448-foot (3,794 m) peak of Mount Erebus. However, due to a typing error in the coordinates when the route was computerised, the printout from Air New Zealand's ground computer system presented at the 9 November briefing corresponded to a southerly flight path down the middle of the wide McMurdo Sound, about 27 miles (43 km) to the west of Mount Erebus.[8] The majority of the previous 13 flights had also entered this flight plan's coordinates into their aircraft navigational systems and flown the McMurdo Sound route, unaware that the route flown did not correspond with the approved route.[9]

Captain Leslie Simpson, the pilot of a flight on 14 November and also present at the 9 November briefing,[10] compared the coordinates of the McMurdo TACAN navigation beacon (about 5 km or 3 mi east of McMurdo NDB), and the McMurdo waypoint that his flight crew had entered into the inertial navigation system (INS), and was surprised to find a large distance between the two. After his flight, Captain Simpson advised Air New Zealand's navigation section of the difference in positions. For reasons that were disputed, this triggered Air New Zealand's navigation section to update the McMurdo waypoint coordinates stored in the ground computer to correspond with the coordinates of the McMurdo TACAN beacon, despite this also not corresponding with the approved route.[8]

The navigation section changed the McMurdo waypoint co-ordinate stored in the ground computer system around 1:40 am on the morning of the flight. Crucially, the flight crew of Flight 901 was not notified of the change. The flight plan printout given to the crew on the morning of the flight, which was subsequently entered by them into the aircraft's INS, differed from the flight plan presented at the 9 November briefing and from Captain Collins' map mark-ups, which he had prepared the night before the fatal flight. The key difference was that the flight plan presented at the briefing corresponded to a track down McMurdo Sound, giving Mount Erebus a wide berth to the east, whereas the flight plan printed on the morning of the flight corresponded to a track that coincided with Mount Erebus, which would result in a collision with Mount Erebus if this leg were flown at an altitude less than 13,000 feet (4,000 m).[9]

The computer program was altered such that the standard telex forwarded to US air traffic controllers (ATCs) at the United States Antarctic science facility at McMurdo Station displayed the word "McMurdo", rather than the coordinates of latitude and longitude, for the final waypoint. During the subsequent inquiry, Justice Mahon concluded that this was a deliberate attempt to conceal from the United States authorities that the flight plan had been changed, and probably because it was known that US Air Traffic Control would lodge an objection to the new flight path.[11]

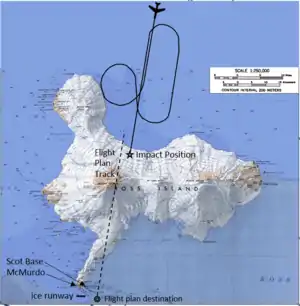

The flight had earlier paused during the approach to McMurdo Sound to carry out a descent, via a figure-eight manoeuvre, through a gap in the low cloud base (later estimated to be at around 2,000 to 3,000 feet (610 to 910 m)) while over water to establish visual contact with surface landmarks and give the passengers a better view.[12] The flight crew either was unaware of or ignored the approved route's minimum safe altitude (MSA) of 16,000 feet (4,900 m) for the approach to Mount Erebus, and 6,000 feet (1,800 m) in the sector south of Mount Erebus (and then only when the cloud base was at 7,000 feet (2,100 m) or better). Photographs and news stories from previous flights showed that many of these had also been flown at levels substantially below the route's MSA. In addition, preflight briefings for previous flights had approved descents to any altitude authorised by the US ATC at McMurdo Station. As the US ATC expected Flight 901 to follow the same route as previous flights down McMurdo Sound, and in accordance with the route waypoints previously advised by Air New Zealand to them, the ATC advised Flight 901 that it had a radar that could let them down to 1,500 feet (460 m). However, the radar equipment did not pick up the aircraft, and the crew also experienced difficulty establishing VHF communications. The distance-measuring equipment did not lock onto the McMurdo Tactical Air Navigation System (TACAN) for any useful period.[13]: 7

Cockpit voice recorder (CVR) transcripts from the last minutes of the flight before impact with Mount Erebus indicated that the flight crew believed they were flying over McMurdo Sound, well to the west of Mount Erebus and with the Ross Ice Shelf visible on the horizon, when in reality they were flying directly toward the mountain. Despite most of the crew being engaged in identifying visual landmarks at the time, they never perceived the mountain directly in front of them. About 6 minutes after completing a descent in visual meteorological conditions, Flight 901 collided with the mountain at an altitude around 1,500 feet (460 m), on the lower slopes of the 12,448-ft-tall (3,794 m) mountain. Passenger photographs taken seconds before the collision removed all doubt of a "flying in cloud" theory, showing perfectly clear visibility well beneath the cloud base, with landmarks 13 miles (21 km) to the left and 10 miles (16 km) to the right of the aircraft visible.[14]

Changes to the coordinates and departure

The crew put the coordinates into the plane's computer before they departed at 7:21 am from Auckland International Airport. Unknown to them, the coordinates had been modified earlier that morning to correct the error introduced previously and undetected until then. The crew evidently did not check the destination waypoint against a topographical map (as did Captain Simpson on the flight of 14 November) or they would have noticed the change. Charts for the Antarctic were not available to the pilot for planning purposes, being withheld until the flight was about to depart. The charts eventually provided, which were carried on the aircraft, were neither comprehensive enough nor large enough in scale to support detailed plotting.[13]: 29

These new coordinates changed the flight plan to track 27 miles (43 km) east of their understanding. The coordinates programmed the plane to overfly Mount Erebus, a 12,448-foot-high (3,794 m) volcano, instead of down McMurdo Sound.[3]

About four hours after a smooth take-off, the flight was 42 miles (68 km) away from McMurdo Station. The radio communications centre there allowed the pilots to descend to 10,000 ft (3,000 m) and to continue "visually". Air-safety regulations at the time did not allow flights to descend to lower than 6,000 ft (1,800 m), even in good weather, although Air New Zealand's own travel magazine showed photographs of previous flights clearly operating below 6,000 ft (1,800 m). Collins believed the plane was over open water.[3]

Crash into Mount Erebus

Collins told McMurdo Station that he would be dropping to 2,000 feet (610 m), at which point he switched control of the aircraft to the automated computer system. Outside, a layer of clouds blended with the white snow-covered volcano, forming a sector whiteout – no contrast between ground and sky was visible to the pilots. The effect deceived everyone on the flight deck, making them believe that the white mountainside was the Ross Ice Shelf, a huge expanse of floating ice derived from the great ice sheets of Antarctica, which was in fact now behind the mountain. As it was little understood, even by experienced polar pilots, Air New Zealand had provided no training for the flight crew on the sector whiteout phenomenon. Consequently, the crew thought they were flying along McMurdo Sound, when they were actually flying over Lewis Bay in front of Mount Erebus.[3]

At 12:49 pm, the ground proximity warning system (GPWS) began sounding a series of "whoop, whoop, pull up" alarms, warning that the plane was dangerously close to terrain. The CVR recorded the following:[nb 2]

- GPWS: "Whoop whoop. Pull up. Whoop whoop..."

- F/E: "Five hundred feet."

- GPWS: "...Pull up."

- F/E: "Four hundred feet."

- GPWS: "Whoop, whoop. Pull up. Whoop whoop. Pull up."

- CA: "Go-around power please."

- GPWS: "Whoop, whoop. Pull-"

- CAM: [Sound of impact]

- End of recording.

The pilots had begun a terrain escape manoeuvre by applying full (go-around) power, but it was too late.[15][16] Six seconds later, the plane crashed into the side of Mount Erebus and exploded, instantly killing everyone on board. The accident occurred at 12:50 pm at a position of 77°25′30″S 167°27′30″E and an elevation of 1,467 feet (447 m) above mean sea level.[13]

McMurdo Station attempted to contact the flight after the crash, and informed Air New Zealand headquarters in Auckland that communication with the aircraft had been lost. United States search-and-rescue personnel were placed on standby.[3]

Nationalities of passengers and crew

Air New Zealand had not lost any passengers to an accident or incident until this event took place.[17] The nationalities of the passengers and crew included:[3][18]

| Country | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| New Zealand | 180 | 20 | 200 |

| Japan | 24 | - | 24 |

| United States | 22 | - | 22 |

| United Kingdom | 6 | - | 6 |

| Canada | 2 | - | 2 |

| Australia | 1 | - | 1 |

| France | 1 | - | 1 |

| Switzerland | 1 | - | 1 |

| Total | 237 | 20 | 257 |

Rescue and recovery

Initial search and discovery

At 2:00 pm, the United States Navy released a situation report stating:

- Air New Zealand Flight 901 has failed to acknowledge radio transmissions. ... One LC-130 fixed-wing aircraft and two UH-1N rotary-wing aircraft are preparing to launch for SAR effort.[19]: 1

Data gathered at 3:43 pm were added to the situation report, stating that the visibility was 40 miles (64 km). Also, six aircraft had been launched to find the flight.[19]: 2

Flight 901 was due to arrive back at Christchurch at 6:05 pm for a stopover including refuelling and a crew change before completing the journey back to Auckland. Around 50 passengers were also supposed to disembark at Christchurch. Airport staff initially told the waiting families that the flight being slightly late was not unusual, but as time went on, it became clear that something was wrong.[20]

At 9:00 pm, about half an hour after the plane would have run out of fuel, Air New Zealand informed the press that it believed the aircraft to be lost. Rescue teams searched along the assumed flight path, but found nothing. At 12:55 am, the crew of a United States Navy aircraft discovered unidentified debris along the side of Mount Erebus.[19]: 4 No survivors could be seen. Around 9:00 am, 20 hours after the crash, helicopters with search parties managed to land on the side of the mountain. They confirmed that the wreckage was that of Flight 901 and that all 237 passengers and 20 crew members had been killed. The DC-10's altitude at the time of the collision was 1,465 feet (447 m).

The vertical stabiliser section of the plane, with the koru logo clearly visible, was found in the snow.[21] Bodies and fragments of the aircraft were flown back to Auckland for identification.[22] The remains of 44 of the victims were not individually identified. A funeral was held for them on 22 February 1980.

Operation Overdue

The recovery effort of Flight 901 was called "Operation Overdue.”

Efforts for recovery were extensive, owing in part to the pressure from Japan, as 24 passengers had been Japanese. The operation lasted until 9 December 1979, with up to 60 recovery workers on site at a time. A team of New Zealand Police officers and a mountain-face rescue team were dispatched on a No. 40 Squadron C-130 Hercules aircraft.

The job of individual identification took many weeks, and was largely done by teams of pathologists, dentists, and police. The mortuary team was led by Inspector Jim Morgan, who collated and edited a report on the recovery operation. Recordkeeping had to be meticulous because of the number and fragmented state of the human remains that had to be identified to the satisfaction of the coroner. The exercise resulted in 83% of the deceased passengers and crew eventually being identified, sometimes from evidence such as a finger capable of yielding a print, or keys in a pocket.[23]

The fact that we all spent about a week camped in polar tents amid the wreckage and dead bodies, maintaining a 24-hour work schedule says it all. We split the men into two shifts (12 hours on and 12 off), and recovered with great effort all the human remains at the site. Many bodies were trapped under tons of fuselage and wings and much physical effort was required to dig them out and extract them.

Initially, there was very little water at the site and we had only one bowl between all of us to wash our hands in before eating. The water was black. In the first days on site, we did not wash plates and utensils after eating, but handed them on to the next shift because we were unable to wash them. I could not eat my first meal on site because it was a meat stew. Our polar clothing became covered in black human grease (a result of burns on the bodies).

We felt relieved when the first resupply of woollen gloves arrived because ours had become saturated in human grease, however, we needed the finger movement that wool gloves afforded, i.e., writing down the details of what we saw and assigning body and grid numbers to all body parts and labelling them. All bodies and body parts were photographed in situ by U.S. Navy photographers who worked with us. Also, U.S. Navy personnel helped us to lift and pack bodies into body bags, which was very exhausting work.

Later, the skua gulls were eating the bodies in front of us, causing us much mental anguish, as well as destroying the chances of identifying the corpses. We tried to shoo them away, but to no avail; we then threw flares, also to no avail. Because of this, we had to pick up all the bodies/parts that had been bagged and create 11 large piles of human remains around the crash site in order to bury them under snow to keep the birds off. To do this we had to scoop up the top layer of snow over the crash site and bury them, only later to uncover them when the weather cleared and the helos were able to get back on the site. It was immensely exhausting work.

After we had almost completed the mission, we were trapped by bad weather and isolated. At that point, NZPO2 and I allowed the liquor that had survived the crash to be given out and we had a party (macabre, but we had to let off steam).

We ran out of cigarettes, a catastrophe that caused all persons, civilians and police on site, to hand in their personal supplies so we could dish them out equally and spin out the supply we had. As the weather cleared, the helos were able to get back and we then were able to hook the piles of bodies in cargo nets under the helicopters and they were taken to McMurdo. This was doubly exhausting because we also had to wind down the personnel numbers with each helo load and that left the remaining people with more work to do. It was exhausting uncovering the bodies and loading them and dangerous, too, as debris from the crash site was whipped up by the helo rotors. Risks were taken by all those involved in this work. The civilians from McDonnell Douglas, MOT, and U.S. Navy personnel were first to leave and then the Police and DSIR followed. I am proud of my service and those of my colleagues on Mount Erebus.[24]

— Jim Morgan

In 2006, the New Zealand Special Service Medal (Erebus) was instituted to recognise the service of New Zealanders, and citizens of the United States of America and other countries, who were involved in the body recovery, identification, and crash investigation phases of Operation Overdue. On 5 June 2009, the New Zealand government recognised some of the Americans who assisted in Operation Overdue during a ceremony in Washington, DC. A total of 40 Americans, mostly Navy personnel, are eligible to receive the medal.[25]

Accident inquiries

Despite Flight 901 crashing in one of the most isolated parts of the world, evidence from the crash site was extensive. Both the cockpit voice recorder and the flight data recorder were in working order and able to be deciphered. Extensive photographic footage from the moments before the crash was available; being a sightseeing flight, most passengers were carrying cameras, from which the majority of the film could be developed.[26][27]

Official accident report

The accident report compiled by New Zealand's chief inspector of air accidents, Ron Chippindale, was released on 12 June 1980. It cited pilot error as the principal cause of the accident and attributed blame to the decision of Collins to descend below the customary minimum altitude level, and to continue at that altitude when the crew was unsure of the plane's position. The customary minimum altitude prohibited descent below 6,000 feet (1,800 m) even under good weather conditions, but a combination of factors led the captain to believe the plane was over the sea (the middle of McMurdo Sound and few small low islands), and previous Flight 901 pilots had regularly flown low over the area to give passengers a better view, as evidenced by photographs in Air New Zealand's own travel magazine and by first-hand accounts of personnel based on the ground at NZ's Scott Base.

Mahon inquiry

In response to public demand, the New Zealand government announced a further one-man Royal Commission of Inquiry into the accident, to be performed by Justice Peter Mahon. This Royal Commission was initially handicapped, in that the deadline was extremely short; originally set for 31 October 1980, it was later extended four times.[28]

Mahon's report, released on 27 April 1981, cleared the crew of blame for the disaster. Mahon said the single, dominant, and effective cause of the crash was Air New Zealand's alteration of the flight plan waypoint coordinates in the ground navigation computer without advising the crew. The new flight plan took the aircraft directly over the mountain, rather than along its flank. Due to whiteout conditions, "a malevolent trick of the polar light", the crew were unable to visually identify the mountain in front of them. Furthermore, they may have experienced a rare meteorological phenomenon called sector whiteout, which creates the visual illusion of a flat horizon far in the distance. A very broad gap between cloud layers appeared to allow a view of the distant Ross Ice Shelf and beyond. Mahon noted that the flight crew, with many thousands of hours of flight time between them, had considerable experience with the extreme accuracy of the aircraft's inertial navigation system. Mahon also found that the preflight briefings for previous flights had approved descents to any altitude authorised by the US ATC at McMurdo Station, and that the radio communications centre at McMurdo Station had indeed authorised Collins to descend to 1,500 feet (460 m), below the minimum safe level of 6,000 feet (1,800 m).

In his report, Mahon found that airline executives and senior pilots had engaged in a conspiracy to whitewash the inquiry, accusing them of "an orchestrated litany of lies" by covering up evidence and lying to investigators.[29]: ¶377 [30] Mahon found that, in the original report, Chippindale had a poor grasp of the flying involved in jet-airline operation, as he (and the New Zealand CAA in general) was typically involved in investigating simple light aircraft crashes. Chippindale's investigation techniques were revealed as lacking in rigour, which allowed errors and avoidable gaps in knowledge to appear in reports. Consequently, Chippindale entirely missed the importance of the flight-plan change and the rare meteorological conditions of Antarctica. Had the pilots been informed of the flight plan change, the crash would have been avoided.

Court proceedings

Judicial review

On 20 May 1981, Air New Zealand applied to the High Court of New Zealand for judicial review of Mahon's order that it pay more than half the costs of the Mahon inquiry, and for judicial review of some of the findings of fact Mahon had made in his report. The application was referred to the Court of Appeal, which unanimously set aside the costs order. The Court of Appeal, by majority, though, declined to go any further, and in particular, declined to set aside Mahon's finding that members of the management of Air New Zealand had conspired to commit perjury before the inquiry to cover up the errors of the ground staff.[28]

Privy Council appeal

Mahon then appealed to the Privy Council in London against the Court of Appeal's decision. His findings as to the cause of the accident, namely reprogramming of the aircraft's flight plan by the ground crew, who then failed to inform the flight crew, had not been challenged before the Court of Appeal, so were not challenged before the Privy Council. His conclusion that the crash was the result of the aircrew being misdirected as to their flight path, not due to pilot error, therefore remained.

Regarding the issue of Air New Zealand stating a minimum altitude of 6,000 feet for pilots in the vicinity of McMurdo Base, the Privy Council stated,

Their Lordships accept unreservedly that ... the evidence given by several of the executive pilots at the inquiry was false. But, even though false ... it cannot have formed part of a predetermined plan of deception. Those witnesses whom the Judge disbelieved on this issue were, as their Lordships must accept, being untruthful ... they were also being singularly naive. [Q]uite apart from the mass of evidence of flights at low altitudes and the publicity given to them ... it is not conceivable that individual witnesses falsely disclaimed knowledge of low flying on previous Antarctic flights in a concerted attempt to deceive anybody.[28]

However, the Law Lords of the Privy Council under the chair of Lord Diplock effectively agreed with some of the views of the minority in the Court of Appeal in concluding that Mahon had acted in breach of natural justice by finding that Air New Zealand management had been engaged in a conspiracy, an accusation which they determined was not supported by the evidence. In its judgment, delivered on 20 October 1983, the Privy Council therefore dismissed Mahon's appeal.[28][31] Aviation researcher John King wrote in his book New Zealand Tragedies, Aviation:

They demolished his case (Mahon's case for a cover-up) item by item, including Exhibit 164, which they said could not "be understood by any experienced pilot to be intended for the purposes of navigation" and went even further, saying there was no clear proof on which to base a finding that a plan of deception, led by the company's chief executive, had ever existed.

"Exhibit 164" was a photocopied diagram of McMurdo Sound showing a southbound flight path passing west of Ross Island and a northbound path passing the island on the east. The diagram did not extend sufficiently far south to show where, how, or even if they joined, and left the two paths disconnected. Evidence had been given to the effect that the diagram had been included in the flight crew's briefing documentation.

Legacy of the disaster

The crash of Flight 901 is one of New Zealand's three deadliest disasters – the others being the 1874 Cospatrick sailing ship disaster in which 470[32][33] people died, and the 1931 Hawke's Bay earthquake, which killed 256 people.[34] At the time of the disaster, it was the fourth-deadliest air crash of all time.[35] As of January 2020, the crash remains Air New Zealand's deadliest accident, as well as New Zealand's deadliest peacetime disaster (excluding the Cospatrick sailing ship disaster, which happened en route to Auckland).[36][37]

Flight 901, in conjunction with the crash of American Airlines Flight 191 in Chicago six months earlier (25 May), severely hurt the reputation of the McDonnell Douglas DC-10. Following the Chicago crash, the FAA withdrew the DC-10's type certificate on 6 June, which grounded all U.S.-registered DC-10s and forbade any foreign government that had a bilateral agreement with the United States regarding aircraft certifications from flying their DC-10s, which included Air New Zealand's seven DC-10s.[38] The Air New Zealand DC-10 fleet was grounded until the FAA measures were rescinded five weeks later, on 13 July, after all carriers had completed modifications that responded to issues discovered from the American Airlines Flight 191 incident.[39]

Flight 901 was the third-deadliest accident involving a DC-10, following Turkish Airlines Flight 981 and American Airlines Flight 191. The event marked the beginning of the end for Air New Zealand's DC-10 fleet, although talk existed before the accident of replacing the aircraft; DC-10s were replaced by Boeing 747s from mid-1981, and the last Air New Zealand DC-10 flew in December 1982. The occurrence also spelled the end of commercially operated Antarctic sightseeing flights – Air New Zealand cancelled all its Antarctic flights after Flight 901, and Qantas suspended its Antarctic flights in February 1980, only returning on a limited basis again in 1994.

Almost all of the aircraft's wreckage still lies where it came to rest on the slopes of Mount Erebus, as both its remote location and its weather conditions can hamper any further recovery operations. During the cold periods, the wreckage is buried under a layer of snow and ice. During warm periods, when snow recedes, it is visible from the air.[40]

Following the incident, all charter flights to Antarctica from New Zealand ceased, and were not resumed until 2013, when a Boeing 747-400 chartered from Qantas set off from Auckland for a sightseeing flight over the continent.[41]

Justice Mahon's report was finally tabled in Parliament by the then-Minister of Transport, Maurice Williamson, in 1999.

In the New Zealand Queen's Birthday Honours list in June 2007, Captain Gordon Vette was awarded the ONZM (Officer of the New Zealand Order of Merit), recognising his services in assisting Justice Mahon during the Erebus inquiry. Vette's book, Impact Erebus, provides a commentary of the flight, its crash, and the subsequent investigations.[42]

In 2008, Justice Mahon was posthumously awarded the Jim Collins Memorial Award by the New Zealand Airline Pilots Association for exceptional contributions to air safety, "in forever changing the general approach used in transport accidents investigations world wide."[43]

In 2009, Air New Zealand's CEO Rob Fyfe apologised to all those affected who did not receive appropriate support and compassion from the company following the incident, and unveiled a commemorative sculpture at its headquarters.[44][45]

On 28 November 2019, the 40-year anniversary of the disaster, New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern, along with the national government, issued a formal apology to the families of the victims. Ardern "[expressed] regret on behalf of Air New Zealand for the accident", and "[apologised] on behalf of the airline which 40 years ago failed in its duty of care to its passengers and staff."[46][47]

The registration of the crashed aircraft, ZK-NZP, has not been reissued.

Memorials

A wooden cross was erected on the mountain above Scott Base to commemorate the accident. It was replaced in 1986 with an aluminium cross after the original was eroded by low temperatures, wind, and moisture.

The memorial for the 16 passengers who were unidentifiable and the 28 whose bodies were never found is at Waikumete Cemetery in Glen Eden, Auckland. Beside the memorial is a Japanese cherry tree, planted as a memorial to the 24 Japanese passengers who died on board Flight 901.[48]

A memorial to the crew members of Flight 901 is located adjacent to Auckland Airport, on Tom Pearce Drive at the eastern end of the airport zone.[49]

In January 2010, a 26-kilogram (57 lb) sculpted koru containing letters written by the loved ones of those who died was placed next to the Antarctic cross.[50] It was originally to have been placed at the site by six relatives of the victims on the 30th anniversary of the crash, 28 November 2009, but this was delayed for two months due to bad weather. It was planned for a second koru capsule, mirroring the first capsule, to be placed at Scott Base in 2011.[51]

The book-length poem "Erebus" by American writer Jane Summer (Sibling Rivalry Press, 2015) memorialises a close friend who died in the tragedy, and in a feat of 'investigative poetry', explores the chain of flawed decisions that caused the crash.[52]

In 2019, it was announced that a national memorial is to be installed in Parnell Rose Gardens, with a relative of one of the crash victims stating that it was the right place.[53][54] However, local residents criticised the memorial's location, saying that it would "destroy the ambiance of the park".[55]

In popular culture

A television miniseries, Erebus: The Aftermath, focusing on the investigation and the Royal Commission of Inquiry, was broadcast in New Zealand and Australia in 1988.[56][57]

The phrase "an orchestrated litany of lies" entered New Zealand popular culture for some years.[58][59][60]

The disaster features in the fifth season-two episode of The Weather Channel documentary Why Planes Crash.[61] The episode is titled "Sudden Impact", and was first aired in January 2015.[61]

Official records

Material related to the Erebus disaster and inquiry is held (with other Antarctica items from the Antarctic Division of the (former) Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR)) by Archives New Zealand, Christchurch. There are 168 record items, of which twelve are restricted access (7 photos, 4 audio cassettes and 1 file of newspaper clippings from Air New Zealand).[62]

Other files are held by Archives New Zealand at Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin.[63] These include files of the Royal Commission (Agency AASJ, accession W2802) and the New Zealand Police (Agencies AAAJ, BBAN; many are restricted).

See also

- Aviation accidents and incidents

- List of New Zealand disasters by death toll

- List of disasters in Antarctica by death toll

- Sensory illusions in aviation

- Tourism in Antarctica

- Similar aircraft incidents

- American Airlines Flight 965, a flight which crashed into terrain after the pilots altered the coordinates.

- Aviateca Flight 901, a flight of the same number which also collided with a volcano.

- Prinair Flight 277

- Ansett New Zealand Flight 703

- New Zealand National Airways Corporation Flight 441

Notes

- At the time of the crash, Air New Zealand had two IATA codes, TE for international flights (a relic from Air New Zealand's predecessor, Tasman Empire Airways Limited (TEAL)) and NZ for domestic flights (acquired from the merger with the National Airways Corporation in April 1978). Despite being domestic flights from an immigration point of view, the Antarctic flights used the TE code for logistical reasons.

- GPWS = ground proximity warning system; CA = captain; F/E = flight engineer; CAM = cockpit-area microphone

References

- Accident description for ZK-NZP at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 24 August 2011.

- "DC-10 playbacks awaited". Flight International: 1987. 15 December 1979. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012.

At press time no information had been released concerning the flightdata and cockpit-voice recorder of Air New Zealand McDonnell Douglas DC-10 ZK-NZP which crashed on Mount Erebus on 28 November.

- "Mt Erebus Plane Crash: DC-10 ZK-NZP, Flight 901". Christchurch City Libraries. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013.

-

- "Visitors to Antarctica – There and Back in a Day". Archived from the original on 24 January 2013.

- "Footnotes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 January 2013.

- "RBNZ – New Zealand Inflation Calculator". Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 11 February 2017.

- "Erebus disaster". NZ History. 9 June 2009. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2009.

- Hickson, Ken (1980). Flight 901 to Erebus. Whitcoulls Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7233-0641-2.

- "Erebus crash site map". New Zealand History online – archived from nzhistory.net.nz. Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2017.

- Mahon, Peter (1984). Verdict on Erebus. Collins. ISBN 0-00-636976-6.

- "Erebus flight briefing". New Zealand History online. Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 4 November 2013.

- Royal Commission Report, para 255(e)

- "Erebus crash site map – NZhistory.net.nz". Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- Transport Accident Investigation Commission (1980). "AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT REPORT No. 79-139: Air New Zealand McDonnell-Douglas DC10-30 ZK-NZP, Ross Island, Antarctica, 28 November 1979" (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Office of Air Accidents Investigation, Ministry of Transport. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2012.

- Royal Commission Report, para 28

- "cvr 791128". planecrashinfo.com. Archived from the original on 21 April 2019. Retrieved 13 April 2019.

- CVR transcript Archived 4 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine from aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 6 February 2008

- Robertson, David. Air NZ likely to switch to 747s. The Sydney Morning Herald: 30 November 1979, p. 2.

- "Erebus Roll of Remembrance". Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

-

- "US Navy SITREP from 28 November 1979 (page 1 of 5)". Archives New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- "US Navy SITREP from 28 November 1979 (page 2 of 5)". Archives New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013.

- "US Navy SITREP from 28 November 1979 (page 3 of 5)". Archives New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013.

- "US Navy SITREP from 28 November 1979 (page 4 of 5)". Archives New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013.

- "US Navy SITREP from 28 November 1979 (page 5 of 5)". Archives New Zealand. Archived from the original on 24 January 2013.

- "Erebus flight overdue = NZHistory.net.nz". Archived from the original on 14 May 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- "Tail of Air New Zealand plane at Mt Erebus". nzhistory.govt.nz. NZHistory, New Zealand history online. Archived from the original on 30 October 2020. Retrieved 26 October 2020.

- Spindler, Bill. "Air New Zealand DC-10 crash into Mt. Erebus". Archived from the original on 25 May 2006. Retrieved 11 July 2006.

- "Operation Overdue". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Archived from the original on 17 January 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- NZPO1 NZAVA–see Bibliography.

- Rejcek, Peter (2 July 2009). "Erebus Medals". The Antarctic Sun. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011.

- "Captain Vette's Research". Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- "A dark passage in NZ history – tvnz.co.nz". 23 October 2009. Archived from the original on 21 November 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- "The Honourable Peter Thomas Mahon (Appeal No. 12 of 1983) v Air New Zealand Limited and Others (New Zealand) 1983 UKPC 29 (20 October 1983)" (PDF). BAILII. 20 October 1983. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 29 July 2016.

- "The Mahon Report". The Erebus Story. Archived from the original on 26 April 2017. Retrieved 23 April 2017.

- Ministry for Culture and Heritage. "Erebus disaster Page 6 – Finding the cause". New Zealand History. Archived from the original on 18 May 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- "1981, Peter Mahon: A lesson learned". The New Zealand Herald. 18 October 1981. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Fire on the Cospatrick". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- John Wilson, The voyage out – Fire on the Cospatrick Archived 3 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, from Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Updated 2007-09-21. Accessed 2008-05-20.

- "Quake will rank among worst disasters". Archived from the original on 14 May 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Spitzer, Aaron (28 November 1999). "Antarctica's darkest day" (PDF). The Antarctic Sun. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016.

- "Erebus disaster Page 1 – Introduction". New Zealand History. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. 15 August 2014. Archived from the original on 30 April 2015. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- "Air NZ apologises for Mt Erebus crash". The Age. Wellington. 24 October 2009. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012.

- North, David M. (12 June 1979). "DC-10 Type Certificate Lifted". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on 14 August 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- Endres, Günter (1998). McDonnell Douglas DC-10. Saint Paul: MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7603-0617-6.

- "TE901 debris reappears on icy slopes of Erebus". The New Zealand Herald. 2 June 2005. ISSN 1170-0777. Archived from the original on 11 April 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "NZ to resume commercial flights to Antarctica". Traveller Online. 5 September 2012. Archived from the original on 9 December 2018. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- "About Gordon Vette". www.erebus.co.nz. Retrieved 19 May 2022.

- "Mahon posthumously awarded". stuff.co.nz. 1 December 2008. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- Address from Rob Fyfe, Air New Zealand CEO, at Unveiling of Momentum Sculpture Archived 1 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Air New Zealand press release, 23 October 2009.

- Fox, Michael (23 October 2009). "Air New Zealand apology 30 years after Erebus tragedy". Stuff.co.nz. Archived from the original on 25 October 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2009.

- Fyfe, James; Vezich, Dianna; Quinlivan, Mark (28 November 2019). "Families of Erebus victims receive an apology from the Government 40 years on". Newshub. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Roy, Eleanor Ainge (28 November 2019). "'The time has come': Ardern apologises for New Zealand's worst air disaster". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Waikumete Cemetery Public Memorial". Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- "Crew Memorial at Auckland Airport". Archived from the original on 13 May 2010. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- "Memorial placed at Mt Erebus crash site". Television New Zealand. 21 January 2010. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- "Ballot drawn for Remembrance flight to Antarctica". Air New Zealand. 30 September 2010. Archived from the original on 6 December 2010. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- "Book Review: "Erebus" - A Brilliant Hybrid That Bears Witness to Tragedy". The Arts Fuse. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Erebus losses 'neglected' for too long - victim's family member". Newshub. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Erebus memorial: Hundreds expected to remember the 257 lives lost". Newshub. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Strong opposition from residents near site of proposed Mt Erebus national memorial". Newshub. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Erebus: The Aftermath (Drama, History), Television New Zealand (TVNZ), retrieved 19 May 2022

- Finlay, Frank (1993), Erebus: the aftermath. Part 1 (of 2). Part 1 (of 2)., London: BBC, OCLC 779036953, retrieved 19 May 2022

- "Banshee Reel". Archived from the original on 30 May 2001. Retrieved 19 November 2007. "a famous quote from NZs recent political past"

- "BREAKING NEWS – FEBRUARY 2004". Citizens for Health Choices. February 2004. Archived from the original on 22 November 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2007. "To quote a well-known phrase, there has been 'An orchestrated litany of lies'"

- "Background Comments on the Stent Report". PSA. April 1998. Archived from the original (DOC) on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 19 November 2007. "...a phrase that is likely to resound as did 'an orchestrated litany of lies' in another investigation"

- Sommers, Caroline (5 January 2015). Why Planes Crash (TV Documentary) (Sudden Impact ed.). The Weather Channel: NBC Peacock Productions. Archived from the original on 13 June 2020. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- "Erebus disaster and inquiry". Archives NZ. 2022.

- "Erebus". Archives NZ. 2022.

Further reading

- NZAVA Operation Deep Freeze – The New Zealand Story, 2002.

- Operation Overdue–NZAVA Archives 2002.

- C.H.N. L'Estrange, The Erebus enquiry: a tragic miscarriage of justice, Auckland, Air Safety League of New Zealand, 1995

- Stuart Macfarlane, The Erebus papers: edited extracts from the Erebus proceedings with commentary, Auckland, Avon Press, 1991

- Report of the Royal Commission to Inquire into the Crash on Mount Erebus, Antarctica of a DC10 Aircraft Operated by Air New Zealand Limited (66 Mb file), Wellington, Government Printer, 1981 (located at Archives New Zealand; item number ABVX 7333 W4772/5025/3/79-139 part 3)

- R Chippendale, Air New Zealand McDonnell-Douglas DC10-30 ZK-NZP, Ross Island, Antarctica 28 November 1979, Office of Air Accidents Investigation, New Zealand Ministry of Transport, Wellington, 1980 (only some parts there)

- Air New Zealand History Page, including a section about Erebus

External links

- "New Zealand DC-10 lost with 257 on Antarctic sightseeing flight" the news of the crash as reported in Flight

- "Antarctic crash crew "misled by management"". Flight International. 119 (3757): 1292. 9 May 1981. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012.

- The Erebus Story – Loss of TE901 (includes Newspaper Articles and Video footage) – New Zealand Air Line Pilots' Association

- Aviation Safety Network: Transcript of flight 901

- The original brochure advertising Air New Zealand flights to Antarctica

- Aircraft Accident Report No 79-139 Air New Zealand McDonnell-Douglas DC10-30 ZK-NZP Ross Island Antarctica 28 November 1979 – the official accident report ("The Chippendale Report")

- Judgments of the Court of Appeal of New Zealand on Proceedings to Review Aspects of the Report of the Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Mount Erebus Aircraft Disaster at Project Gutenberg

- (audio file) ABC Radio National program "Ockham's Razor": "Arthur Marcell takes us through some of the events leading up to the crash and has a few questions for modern navigators." transcript

- NZ Special Service Medal (Erebus) 2006

- Erebus disaster (NZHistory.net.nz)–includes previously unpublished images and sound files

- Erebus Aircraft Accident–Christchurch City Libraries

- Erebus for Kids–This site is for young school children to provide information about the Erebus Tragedy.

- "Jim Tucker: The man who chronicled "Litany of Lies"". Stuff/Fairfax. 21 December 2017.

- Erebus Disaster: Lookout – official TV New Zealand YouTube site with programme on the Royal Commission enquiry into the crash.

- Erebus Memorial: Erebus Memorial Names – official New Zealand Ministry for Culture & Heritage memorial site.

- BBC News: The plane crash that changed New Zealand