Jackfruit

The jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus), also known as jack tree,[7] is a species of tree in the fig, mulberry, and breadfruit family (Moraceae).[8] Its origin is in the region between the Western Ghats of southern India, all of Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and the rainforests of the Philippines, Indonesia, and Malaysia.[8][9][10][11]

| Jackfruit | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Rosales |

| Family: | Moraceae |

| Genus: | Artocarpus |

| Species: | A. heterophyllus |

| Binomial name | |

| Artocarpus heterophyllus | |

| Synonyms[3][4][5][6] | |

| |

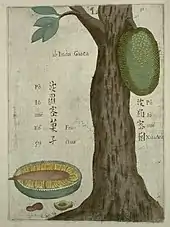

The jack tree is well-suited to tropical lowlands, and is widely cultivated throughout tropical regions of the world. It bears the largest fruit of all trees, reaching as much as 55 kg (120 pounds) in weight, 90 cm (35 inches) in length, and 50 cm (20 inches) in diameter.[8][12] A mature jack tree produces some 200 fruits per year, with older trees bearing up to 500 fruits in a year.[8][9] The jackfruit is a multiple fruit composed of hundreds to thousands of individual flowers, and the fleshy petals of the unripe fruit are eaten.[8][13] The ripe fruit is sweet (depending on variety) and is more often used for desserts. Canned green jackfruit has a mild taste and meat-like texture that lends itself to being called a "vegetable meat".[8]

Jackfruit is commonly used in South and Southeast Asian cuisines.[14][15] Both ripe and unripe fruits are consumed. It is available internationally canned or frozen and in chilled meals as are various products derived from the fruit such as noodles and chips.

Etymology and common name

The word jackfruit comes from Portuguese jaca, which in turn is derived from the Malayalam language term chakka (Malayalam: chakka pazham),[13][16] when the Portuguese arrived in India at Kozhikode (Calicut) on the Malabar Coast (Kerala) in 1499. Later the Malayalam name ചക്ക (cakka) was recorded by Hendrik van Rheede (1678–1703) in the Hortus Malabaricus, vol. iii in Latin. Henry Yule translated the book in Jordanus Catalani's (fl. 1321–1330) Mirabilia descripta: the wonders of the East.[17] This term is in turn derived from the Proto-Dravidian root kā(y) ("fruit, vegetable").[18]

The common English name "jackfruit" was used by physician and naturalist Garcia de Orta in his 1563 book Colóquios dos simples e drogas da India.[19][20] Centuries later, botanist Ralph Randles Stewart suggested it was named after William Jack (1795–1822), a Scottish botanist who worked for the East India Company in Bengal, Sumatra, and Malaya.[21]

History

The jackfruit was domesticated independently in South Asia and Southeast Asia, as indicated by the Southeast Asian names which are not derived from the Sanskrit roots. It was probably first domesticated by Austronesians in Java or the Malay Peninsula. The fruit was later introduced to Guam via Filipino settlers when both were part of the Spanish Empire.[22][23] It is the national fruit of Bangladesh[24] and the state fruit of Kerala.

Botanical description

Shape, trunk and leaves

Artocarpus heterophyllus grows as an evergreen tree that has a relatively short trunk with a dense treetop. It easily reaches heights of 10 to 20 m (33 to 66 feet) and trunk diameters of 30 to 80 cm (12 to 31 inches). It sometimes forms buttress roots. The bark of the jackfruit tree is reddish-brown and smooth. In the event of injury to the bark, a milky juice is released.

The leaves are alternate and spirally arranged. They are gummy and thick and are divided into a petiole and a leaf blade. The petiole is 2.5 to 7.5 cm (1 to 3 inches) long. The leathery leaf blade is 20 to 40 cm (7 to 15 inches) long, and 7.5 to 18 cm (3 to 7 inches) wide and is oblong to ovate in shape.

In young trees, the leaf edges are irregularly lobed or split. On older trees, the leaves are rounded and dark green, with a smooth leaf margin. The leaf blade has a prominent main nerve and starting on each side six to eight lateral nerves. The stipules are egg-shaped at a length of 1.5 to 8 cm (9⁄16 to 3+1⁄8 inches).

Flowers and fruit

The inflorescences are formed on the trunk, branches or twigs (cauliflory). Jackfruit trees are monoecious, having both female and male flowers on a tree. The inflorescences are pedunculated, cylindrical to ellipsoidal or pear-shaped, to about 10–12 cm (3+15⁄16–4+3⁄4 inches) long and 5–7 cm (2–3 inches) wide. Inflorescences are initially completely enveloped in egg-shaped cover sheets which rapidly slough off.

The flowers are small, sitting on a fleshy rachis.[25] The male flowers are greenish, some flowers are sterile. The male flowers are hairy and the perianth ends with two 1 to 1.5 mm (3⁄64 to 1⁄16 in) membrane. The individual and prominent stamens are straight with yellow, roundish anthers. After the pollen distribution, the stamens become ash-gray and fall off after a few days. Later all the male inflorescences also fall off. The greenish female flowers, with hairy and tubular perianth, have a fleshy flower-like base. The female flowers contain an ovary with a broad, capitate, or rarely bilobed scar. The blooming time ranges from December until February or March.

The ellipsoidal to roundish fruit is a multiple fruit formed from the fusion of the ovaries of multiple flowers. The fruits grow on a long and thick stem on the trunk. They vary in size and ripen from an initially yellowish-greenish to yellow, and then at maturity to yellowish-brown. They possess a hard, gummy shell with small pimples surrounded with hard, hexagonal tubercles. The large and variously shaped fruit have a length of 30 to 100 cm (10 to 40 inches) and a diameter of 15 to 50 cm (6 to 20 inches) and can weigh 10–25 kg (22–55 pounds) or more.[8]

The fruits consist of a fibrous, whitish core (rachis) about 5–10 cm (2–4 inches) thick. Radiating from this are many 10-centimeter-long (4 in) individual fruits. They are elliptical to egg-shaped, light brownish achenes with a length of about 3 cm (1+1⁄8 inches) and a diameter of 1.5 to 2 cm (9⁄16 to 13⁄16 inch).

There may be about 100–500 seeds per fruit. The seed coat consists of a thin, waxy, parchment-like and easily removable testa (husk) and a brownish, membranous tegmen. The cotyledons are usually unequal in size, and the endosperm is minimally present.[26] An average fruit consists of 27% edible seed coat, 15% edible seeds, 20% white pulp (undeveloped perianth, rags) and bark and 10% core.

The fruit matures during the rainy season from July to August. The bean-shaped achenes of the jackfruit are coated with a firm yellowish aril (seed coat, flesh), which has an intense sweet taste at maturity of the fruit. The pulp is enveloped by many narrow strands of fiber (undeveloped perianth), which run between the hard shell and the core of the fruit and are firmly attached to it. When pruned, the inner part (core) secretes a sticky, milky liquid,[8] which can hardly be removed from the skin, even with soap and water. To clean the hands after "unwinding" the pulp an oil or other solvent is used. For example, street vendors in Tanzania, who sell the fruit in small segments, provide small bowls of kerosene for their customers to cleanse their sticky fingers. When fully ripe, jackfruit has a strong pleasant aroma, the pulp of the opened fruit resembles the odor of pineapple and banana.[8]

Food

Ripe jackfruit is naturally sweet, with subtle pineapple- or banana-like flavor.[8] It can be used to make a variety of dishes, including custards, cakes, or mixed with shaved ice as es teler in Indonesia or halo-halo in the Philippines. For the traditional breakfast dish in southern India, idlis, the fruit is used with rice as an ingredient and jackfruit leaves are used as a wrapping for steaming. Jackfruit dosas can be prepared by grinding jackfruit flesh along with the batter. Ripe jackfruit arils are sometimes seeded, fried, or freeze-dried and sold as jackfruit chips.

The seeds from ripe fruits are edible once cooked, and are said to have a milky, sweet taste often compared to Brazil nuts. They may be boiled, baked, or roasted.[8] When roasted, the flavor of the seeds is comparable to chestnuts. Seeds are used as snacks (either by boiling or fire-roasting) or to make desserts. In Java, the seeds are commonly cooked and seasoned with salt as a snack. They are commonly used in curry in India in the form of a traditional lentil and vegetable mix curry. Young leaves are tender enough to be used as a vegetable.[8]

Aroma

Jackfruit has a distinctive sweet and fruity aroma. In a study of flavour volatiles in five jackfruit cultivars, the main volatile compounds detected were ethyl isovalerate, propyl isovalerate, butyl isovalerate, isobutyl isovalerate, 3-methylbutyl acetate, 1-butanol, and 2-methylbutan-1-ol.[27]

A fully ripe and unopened jackfruit is known to "emit a strong aroma" – perhaps unpleasant[8][28] – with the inside of the fruit described as smelling of pineapple and banana.[8] After roasting, the seeds may be used as a commercial alternative to chocolate aroma.[29]

Nutritional value

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 397 kJ (95 kcal) |

23.25 g | |

| Sugars | 19.08 g |

| Dietary fiber | 1.5 g |

0.64 g | |

Protein | 1.72 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. beta-Carotene lutein zeaxanthin | 1% 5 μg1% 61 μg157 μg |

| Thiamine (B1) | 9% 0.105 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) | 5% 0.055 mg |

| Niacin (B3) | 6% 0.92 mg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 5% 0.235 mg |

| Vitamin B6 | 25% 0.329 mg |

| Folate (B9) | 6% 24 μg |

| Vitamin C | 17% 13.8 mg |

| Vitamin E | 2% 0.34 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Calcium | 2% 24 mg |

| Iron | 2% 0.23 mg |

| Magnesium | 8% 29 mg |

| Manganese | 2% 0.043 mg |

| Phosphorus | 3% 21 mg |

| Potassium | 10% 448 mg |

| Sodium | 0% 2 mg |

| Zinc | 1% 0.13 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 73.5 g |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

The edible pulp is 74% water, 23% carbohydrates, 2% protein, and 1% fat. The carbohydrate component is primarily sugars, and is a source of dietary fiber. In a 100-gram (3+1⁄2-ounce) portion, raw jackfruit provides 400 kJ (95 kcal), and is a rich source (20% or more of the Daily Value, DV) of vitamin B6 (25% DV). It contains moderate levels (10-19% DV) of vitamin C and potassium, with no significant content of other micronutrients.

The jackfruit is a partial solution for food security in developing countries.[13][30]

Culinary uses

The flavor of the ripe fruit is comparable to a combination of apple, pineapple, mango, and banana.[8][14] Varieties are distinguished according to characteristics of the fruit flesh. In Indochina, the two varieties are the "hard" version (crunchier, drier, and less sweet, but fleshier), and the "soft" version (softer, moister, and much sweeter, with a darker gold-color flesh than the hard variety). Unripe jackfruit has a mild flavor and meat-like texture and is used in curry dishes with spices in many cuisines. The skin of unripe jackfruit must be peeled first, then the remaining jackfruit flesh is chopped into edible portions and cooked before serving. The final chunks resemble prepared artichoke hearts in their mild taste, color, and flowery qualities.

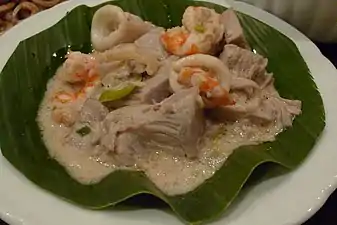

The cuisines of many Asian countries use cooked young jackfruit.[14] In many cultures, jackfruit is boiled and used in curries as a staple food. The boiled young jackfruit is used in salads or as a vegetable in spicy curries and side dishes, and as fillings for cutlets and chops. It may be used by vegetarians as a substitute for meat such as pulled pork, though the protein content of the fruit is not significant. It may be cooked with coconut milk and eaten alone or with meat, shrimp or smoked pork. In southern India, unripe jackfruit slices are deep-fried to make chips.

South Asia

In Bangladesh, the fruit is consumed on its own. The unripe fruit is used in curry, and the seed is often dried and preserved to be later used in curry.[31] In India, two varieties of jackfruit predominate: muttomvarikka and sindoor. Muttomvarikka has a slightly hard inner flesh when ripe, while the inner flesh of the ripe sindoor fruit is soft.[32]

A sweet preparation called chakkavaratti (jackfruit jam) is made by seasoning pieces of muttomvarikka fruit flesh in jaggery, which can be preserved and used for many months. The fruits are either eaten alone or as a side to rice. The juice is extracted and either drunk straight or as a side. The juice is sometimes condensed and eaten as candies. The seeds are either boiled or roasted and eaten with salt and hot chilies. They are also used to make spicy side dishes with rice. Jackfruit may be ground and made into a paste, then spread over a mat and allowed to dry in the sun to create a natural chewy candy.

Jackfruit curry (Sri Lanka)

Jackfruit curry (Sri Lanka) Green jackfruit and potato curry (West Bengal)

Green jackfruit and potato curry (West Bengal) Jackfruit masala (India)

Jackfruit masala (India) Jackfruit fried in coconut oil from Kerala, India

Jackfruit fried in coconut oil from Kerala, India_Cutlet.jpg.webp) Jackfruit (unripe) cutlet, India

Jackfruit (unripe) cutlet, India

Southeast Asia

In Indonesia and Malaysia, jackfruit is called nangka. The ripe fruit is usually sold separately and consumed on its own, or sliced and mixed with shaved ice as a sweet concoction dessert such as es campur and es teler. The ripe fruit might be dried and fried as kripik nangka, or jackfruit cracker. The seeds are boiled and consumed with salt, as they contain edible starchy content; this is called beton. Young (unripe) jackfruit is made into curry called gulai nangka or stewed called gudeg.

In the Philippines, jackfruit is called langka in Filipino and nangkà[33] in Cebuano. The unripe fruit is usually cooked in coconut milk and eaten with rice; this is called ginataang langka.[34] The ripe fruit is often an ingredient in local desserts such as halo-halo and the Filipino turon. The ripe fruit, besides also being eaten raw as it is, is also preserved by storing in syrup or by drying. The seeds are also boiled before being eaten.

Thailand is a major producer of jackfruit, which are often cut, prepared, and canned in a sugary syrup (or frozen in bags or boxes without syrup) and exported overseas, frequently to North America and Europe.

In Vietnam, jackfruit is used to make jackfruit chè, a sweet dessert soup, similar to the Chinese derivative bubur cha cha. The Vietnamese also use jackfruit purée as part of pastry fillings or as a topping on xôi ngọt (a sweet version of sticky rice portions).

Jackfruits are found primarily in the eastern part of Taiwan. The fresh fruit can be eaten directly or preserved as dried fruit, candied fruit, or jam. It is also stir-fried or stewed with other vegetables and meat.

Kripik nangka, jackfruit chips (Indonesia)

Kripik nangka, jackfruit chips (Indonesia)

Gudeg (left), jackfruit curry with palm sugar (Indonesia)

Gudeg (left), jackfruit curry with palm sugar (Indonesia) Ginataang langka, jackfruit in coconut milk (Philippines)

Ginataang langka, jackfruit in coconut milk (Philippines) Halo-halo, shaved ice dessert with various fruits and toppings (Philippines)

Halo-halo, shaved ice dessert with various fruits and toppings (Philippines)

Americas

In Brazil, three varieties are recognized: jaca-dura, or the "hard" variety, which has a firm flesh, and the largest fruits that can weigh between 15 and 40 kg each; jaca-mole, or the "soft" variety, which bears smaller fruits with a softer and sweeter flesh; and jaca-manteiga, or the "butter" variety, which bears sweet fruits whose flesh has a consistency intermediate between the "hard" and "soft" varieties.[35]

Africa

From a tree planted for its shade in gardens, it became an ingredient for local recipes using different fruit segments. The seeds are boiled in water or roasted to remove toxic substances, and then roasted for a variety of desserts. The flesh of the unripe jackfruit is used to make a savory salty dish with smoked pork. The jackfruit arils are used to make jams or fruits in syrup, and can also be eaten raw.

Wood and manufacturing

The golden yellow timber with good grain is used for building furniture and house construction in India. It is termite-resistant[36] and is superior to teak for building furniture. The wood of the jackfruit tree is important in Sri Lanka and is exported to Europe. Jackfruit wood is widely used in the manufacture of furniture, doors and windows, in roof construction,[8] and fish sauce barrels.[37]

The wood of the tree is used for the production of musical instruments. In Indonesia, hardwood from the trunk is carved out to form the barrels of drums used in the gamelan, and in the Philippines, its soft wood is made into the body of the kutiyapi, a type of boat lute. It is also used to make the body of the Indian string instrument veena and the drums mridangam, thimila, and kanjira.[38]

Cultural significance

The jackfruit has played a significant role in Indian agriculture for centuries. Archaeological findings in India have revealed that jackfruit was cultivated in India 3000 to 6000 years ago.[39] It has also been widely cultivated in Southeast Asia.

The ornate wooden plank called avani palaka, made of the wood of the jackfruit tree, is used as the priest's seat during Hindu ceremonies in Kerala. In Vietnam, jackfruit wood is prized for the making of Buddhist statues in temples[40] The heartwood is used by Buddhist forest monastics in Southeast Asia as a dye, giving the robes of the monks in those traditions their distinctive light-brown color.[41]

Jackfruit is the national fruit of Bangladesh,[31] and the state fruit of the Indian states of Kerala (which hosts jackfruit festivals) and Tamil Nadu.[42][43]

Cultivation

In terms of taking care of the plant, minimal pruning is required; cutting off dead branches from the interior of the tree is only sometimes needed.[8] In addition, twigs bearing fruit must be twisted or cut down to the trunk to induce growth for the next season.[8] Branches should be pruned every three to four years to maintain productivity.[8]

Some trees carry too many mediocre fruits and these are usually removed to allow the others to develop better to maturity.

Stingless bees such as Tetragonula iridipennis are jackfruit pollinators, and so play an important role in jackfruit cultivation. It seems to be the case that pollination results from a three-way mutualism involving the flower, a fungus, and a species of gall midge, Clinidiplosis ultracrepidata. The fungus forms a film over the syncarps which is a food source to both the fly larvae and adults.[44]

Production and marketing

In 2017, India produced 1.4 million tonnes of jackfruit, followed by Bangladesh, Thailand, and Indonesia.[45]

The marketing of jackfruit involves three groups: producers, traders, and middlemen, including wholesalers and retailers.[46] The marketing channels are rather complex. Large farms sell immature fruit to wholesalers, which helps cash flow and reduces risk, whereas medium-sized farms sell the fruit directly to local markets or retailers.

_-_photo_of_the_inside.jpg.webp) Packed jackfruit sold in a market

Packed jackfruit sold in a market Selling jackfruit in Bangkok

Selling jackfruit in Bangkok Jackfruit at a fruit stand in Manhattan's Chinatown

Jackfruit at a fruit stand in Manhattan's Chinatown Cut jackfruit

Cut jackfruit Polythene-packaged cut jackfruit

Polythene-packaged cut jackfruit Extracting the jackfruit arils and separating the seeds from the flesh

Extracting the jackfruit arils and separating the seeds from the flesh

Commercial availability

Outside countries of origin, fresh jackfruit can be found at food markets throughout Southeast Asia.[8][47] It is also extensively cultivated in the Brazilian coastal region, where it is sold in local markets. It is available canned in sugary syrup, or frozen, already prepared and cut. Jackfruit industries are established in Sri Lanka and Vietnam, where the fruit is processed into products such as flour, noodles, papad, and ice cream.[47] It is also canned and sold as a vegetable for export.

Jackfruit is also widely available year-round, both canned and dried. Dried jackfruit chips are produced by various manufacturers. As reported in 2019, jackfruit became more widely available in US grocery stores, cleaned and ready to cook, as well as in premade dishes or prepared ingredients.[48] It is on restaurant menus in preparations such as taco fillings and vegan versions of pulled pork dishes.[48]

Invasive species

In Brazil, the jackfruit can become an invasive species as in Brazil's Tijuca Forest National Park in Rio de Janeiro[49] or at the Horto Florestal in neighbouring Niterói. The Tijuca is mostly an artificial secondary forest, whose planting began during the mid-nineteenth century; jackfruit trees have been a part of the park's flora since it was founded.

The species has expanded excessively because its fruits, which naturally fall to the ground and open, are eagerly eaten by small mammals, such as the common marmoset and coati. The seeds are then dispersed by these animals, spreading jackfruit trees that compete for space with native tree species. The supply of jackfruit has allowed the marmoset and coati populations to expand. Since both prey opportunistically on bird eggs and nestlings, the increases in marmoset and coati populations are detrimental to local birds.

See also

- Domesticated plants and animals of Austronesia

- Chempedak, a closely related Southeast Asian fruit sometimes confused with jackfruit

- Durian, a fruit similar in appearance but from an unrelated tree, also from Southeast Asia

References

- Under its accepted name Artocarpus heterophyllus (then as heterophylla) this species was described in Encyclopédie Méthodique, Botanique 3: 209. (1789) by Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, from a specimen collected by botanist Philibert Commerson. Lamarck said of the fruit that it was coarse and difficult to digest. Larmarck's original description of tejas. Vol. t.3. Panckoucke;Plomteux. 1789. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

On mange la chair de son fruit, ainsi que les noyaux qu'il contient; mais c'est un aliment grossier et difficile à digérer.

- "Name - !Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam". Tropicos. Saint Louis, Missouri: Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "TPL, treatment of Artocarpus heterophyllus". The Plant List; Version 1. (published on the internet). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and Missouri Botanical Garden. 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "Name – Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. synonyms". Tropicos. Saint Louis, Missouri: Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "Artocarpus heterophyllus". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. — The Plant List". Theplantlist.org. 23 March 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- "Artocarpus heterophyllus". Tropical Biology Association. October 2006. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- Morton, Julia. "Jackfruit". Center for New Crops & Plant Products, Purdue University Department of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- Love, Ken; Paull, Robert E (June 2011). "Jackfruit" (PDF). College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

- Boning, Charles R. (2006). Florida's Best Fruiting Plants:Native and Exotic Trees, Shrubs, and Vines. Sarasota, Florida: Pineapple Press, Inc. p. 107.

- Elevitch, Craig R.; Manner, Harley I. (2006). "Artocarpus heterophyllus (Jackfruit)". In Elevitch, Craig R. (ed.). Traditional Trees of Pacific Islands: Their Culture, Environment, and Use. Permanent Agriculture Resources. p. 112. ISBN 9780970254450.

- "Jackfruit Fruit Facts". California Rare Fruit Growers, Inc. 1996. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- Silver, Mark (May 2014). "Here's The Scoop On Jackfruit, A Ginormous Fruit To Feed The World". NPR. NPR. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- Janick, Jules; Paull, Robert E. The encyclopedia of fruit & nuts (PDF). p. 155.

- The encyclopedia of fruit & nuts, By Jules Janick, Robert E. Paull, pp. 481–485

- Pradeepkumar, T.; Jyothibhaskar, B. Suma; Satheesan, K. N. (2008). Prof. K. V. Peter (ed.). Management of Horticultural Crops. Horticultural Science Series. Vol. 11. New Delhi, India: New India Publishing. p. 81. ISBN 978-81-89422-49-3.

The English name jackfruit is derived from Portuguese jaca, which is derived from Malayalam chakka,

- Friar Jordanus, 14th century, as translated from the Latin by Henry Yule (1863). Mirabilia descripta: the wonders of the East. Hakluyt Society. p. 13. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Southworth, Franklin (2 August 2004). Linguistic Archaeology of South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 9781134317769 – via Google Books.

- Oxford English Dictionary, Second Edition, 1989, online edition

- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. Bartleby. 2000. Archived from the original on 30 November 2005.

- Stewart, Ralph R. (1984). "How Did They Die?" (PDF). Taxon. 33 (1): 48–52. doi:10.2307/1222028. hdl:2027.42/149689. JSTOR 1222028.

- Blench, Roger= (2008). "A history of fruits on the Southeast Asian mainland" (PDF). In Osada, Toshiki; Uesugi, Akinori (eds.). Occasional Paper 4: Linguistics, Archaeology and the Human Past. Indus Project. pp. 115–137. ISBN 9784902325331.

- Blust, Robert; Trussel, Stephen (2013). "The Austronesian Comparative Dictionary: A Work in Progress". Oceanic Linguistics. 52 (2): 493–523. doi:10.1353/ol.2013.0016. S2CID 146739541.

- "Jackfruit – National Fruit of Bangladesh". By Bangladesh.com. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- Pushpakumara, D. K. N. G. (2006). "Floral and Fruit Morphology and Phenology of Artocarpus heterophyllus Lam. (Moraceae)". Sri Lankan J. Agric. Sci. 43: 82–106.

- N. Haq (2006). Jackfruit Artocarpus heterophyllus; Volume 10 of Fruits for the Future; p 4-11, 72 f. International Center for Underutilized Crops. ISBN 0854327851.

- Ong, B.T.; Nazimah, S.A.H.; Tan, C.P.; Mirhosseini, H.; Osman, A.; Hashim, D. Mat; Rusul, G. (August 2008). "Analysis of volatile compounds in five jackfruit (Artocarpus heterophyllus L.) cultivars using solid-phase microextraction (SPME) and gas chromatography-time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC-TOFMS)". Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 21 (5): 416–422. doi:10.1016/j.jfca.2008.03.002.

- Hargreaves, Dorothy; Hargreaves, Bob (1964). Tropical Trees of Hawaii. Kailua, Hawaii: Hargreaves. p. 30. ISBN 9780910690027.

- Spada, Fernanda Papa; et al. (21 January 2017). "Optimization of Postharvest Conditions To Produce Chocolate Aroma from Jackfruit Seeds" (PDF). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 65 (6): 1196–1208. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.6b04836. PMID 28110526.

- Mwandambo, Pascal (11 March 2014). "Venture in rare jackfruit turns farmers' fortunes around". Standard Online. Standard Group Ltd. Retrieved 20 December 2016.

- Matin, Abdul. "A poor man's fruit: Now a miracle food!". The Daily Star. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- Ashwini. A (2015). Morpho-Molecular Characterization of Jackfruit. Artocarpus heterophyllus (Thesis). Kerala Agricultural University.

- Wolff, John U. (1972). "Nangkà" (PDF). A Dictionary of Cebuano Visayan. Vol. 2. p. 698.

- "Ginataang Langka (Jackfruit in Coconut Milk)". Filipino Chow. 20 May 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2019.

- General information Archived 2009-04-13 at the Wayback Machine, Department of Agriculture, State of Bahia

- Bali, KALIUDA Gallery (30 January 2021). "All About Jackfruit Wood or Jackwood". KALIUDA Gallery Bali. Retrieved 17 September 2021.

- "Nam O fish sauce village". Danang Today. 26 February 2014. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- Chauhan, Chandrashekhar; Singru, P. M.; Vathsan, Radhika (31 March 2021). "The effect of the extended bridge on the Timbre of the Sarasvati Veena: a numerical and experimental study". Journal of Measurements in Engineering. 9 (1): 23–35. doi:10.21595/jme.2020.21712. ISSN 2335-2124.

- Preedy, Victor R.; Watson, Ronald Ross; Patel, Vinood B., eds. (2011). Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention (1st ed.). Burlington, MA: Academic Press. p. 678. ISBN 978-0-12-375689-3.

- "Gỗ mít nài". Nhagoviethung.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2017. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- Forest Monks and the Nation-state: An Anthropological and Historical Study in Northeast Thailand, J.L. Taylor 1993 p. 218

- Subrahmanian, N.; Hikosaka, Shu; Samuel, G. John; Thiagarajan, P. (1997). Tamil social history. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 88. Retrieved 23 March 2010.

- "Kerala's State fruit!". Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- Balcombe, Jonathan (2021). Super Fly: The Unexpected Lives of the World's Most Successful Insects. New York: Penguin Books. p. 152. ISBN 9780143134275.

- Benjamin Elisha Sawe (25 April 2017). "World Leaders In Jackfruit Production". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 23 May 2018.

- Haq, Nazmul (2006). Jackfruit: Artocarpus heterophyllus (PDF). Southampton, UK: Southampton Centre for Underutilised Crops. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-85432-785-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2012.

- Goldenberg, Suzanne (23 April 2014). "Jackfruit heralded as 'miracle' food crop". The Guardian, London, UK. Retrieved 17 October 2016.

- Brian Kateman (20 August 2019). "This Ancient 'Miracle Fruit' Is The Latest Meat Replacement Craze". Forbes. Retrieved 2 September 2019.

- "Danger or delight? Uphill battle for Brazil's huge jackfruit". ABC News.

External links

Jackfruit at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject

Jackfruit at the Wikibooks Cookbook subproject Media related to Artocarpus heterophyllus (category) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Artocarpus heterophyllus (category) at Wikimedia Commons Data related to Artocarpus heterophyllus at Wikispecies

Data related to Artocarpus heterophyllus at Wikispecies The dictionary definition of jackfruit at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of jackfruit at Wiktionary