Astarte

Astarte (/əˈstɑːrtiː/; Ασταρτη, Astartē) is the Hellenized form of the Ancient Near Eastern goddess Ashtart or Athtart (Northwest Semitic), a deity closely related to Ishtar (East Semitic), who was worshipped from the Bronze Age through classical antiquity. The name is particularly associated with her worship in the ancient Levant among the Canaanites and Phoenicians, though she was originally associated with Amorite cities like Ugarit and Emar, as well as Mari and Ebla.[5] She was also celebrated in Egypt, especially during the reign of the Ramessides, following the importation of foreign cults there. Phoenicians introduced her cult in their colonies on the Iberian Peninsula.

| Astarte | |

|---|---|

Goddess of war, hunting, love | |

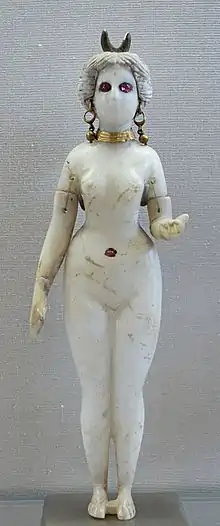

Statuette figurine of a goddess with a horned headdress, Louvre Museum, possibly Ishtar, Astarte or Nanaya. From the necropolis of Hillah, near Babylon. | |

| Major cult center | Ugarit, Emar, Sidon, Tyre |

| Planet | possibly Venus |

| Symbols | lion, horse, chariot |

| Parents | Epigeius and Ge (Hellenised Phoenician tradition) Ptah or Ra (in Egyptian tradition) |

| Consort | possibly Baal (Hadad)[1][2] |

| Equivalents | |

| Greek equivalent | Aphrodite |

| Roman equivalent | Venus |

| Mesopotamian equivalent | Ishtar |

| Sumerian equivalent | Inanna |

| Hurrian equivalent | Ishara;[3] Shaushka[4] |

| Deities of the ancient Near East |

|---|

| Religions of the ancient Near East |

Name

Astarte was a goddess of both the Canaanite and the Phoenician pantheon, derived from an earlier Syrian deity. She is recorded in Akkadian as ᵈAs-dar-tú (![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ), the feminine form of Ishtar.[6] The name appears in Ugaritic as ʿAṯtart (𐎓𐎘𐎚𐎗𐎚), in Phoenician as ʿAštart (𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕), in Hebrew as ʿAštōreṯ (עַשְׁתֹּרֶת).[6]

), the feminine form of Ishtar.[6] The name appears in Ugaritic as ʿAṯtart (𐎓𐎘𐎚𐎗𐎚), in Phoenician as ʿAštart (𐤏𐤔𐤕𐤓𐤕), in Hebrew as ʿAštōreṯ (עַשְׁתֹּרֶת).[6]

Overview

In various cultures Astarte was connected with some combination of the following spheres: war, sexuality, royal power, healing and - especially in Ugarit and Emar - hunting;[7] however, known sources do not indicate she was a fertility goddess, contrary to opinions in early scholarship.[8] Her symbol was the lion and she was also often associated with the horse and by extension chariots. The dove might be a symbol of her as well, as evidenced by some Bronze Age cylinder seals.[9] The only images identified with absolute certainty as Astarte as these depicting her as a combatant on horseback or in a chariot.[10] While many authors in the past asserted that she has been known as the deified morning and/or evening star,[6] it has been called into question if she had an astral character at all, at least in Ugarit and Emar.[11] God lists known from Ugarit and other prominent Bronze Age Syrian cities regarded her as the counterpart of Assyro-Babylonian goddess Ištar, and of the Hurrian Ishtar-like goddesses Ishara (presumably in her aspect of "lady of love") and Shaushka; in some cities, the western forms of the name and the eastern form "Ishtar" were fully interchangeable.[12]

In later times Astarte was worshipped in Syria and Canaan. Her worship spread to Cyprus, where she may have been merged with an ancient Cypriot goddess. This merged Cypriot goddess may have been adopted into the Greek pantheon in Mycenaean and Dark Age times to form Aphrodite. It has been argued, however, that Astarte's character was less erotic and more warlike than Ishtar originally was, perhaps because she was influenced by the Canaanite goddess Anat, and that therefore Ishtar, not Astarte, was the direct forerunner of the Cypriot goddess. Greeks in classical, Hellenistic, and Roman times occasionally equated Aphrodite with Astarte and many other Near Eastern goddesses, in keeping with their frequent practice of syncretizing other deities with their own.[13]

Major centers of Astarte's worship in the Iron Age were the Phoenician city-states of Sidon, Tyre, and Byblos. Coins from Sidon portray a chariot in which a globe appears, presumably a stone representing Astarte. "She was often depicted on Sidonian coins as standing on the prow of a galley, leaning forward with right hand outstretched, being thus the original of all figureheads for sailing ships."[14] In Sidon, she shared a temple with Eshmun. Coins from Beirut show Poseidon, Astarte, and Eshmun worshipped together.

Other significant locations where she was introduced by Phoenician sailors and colonists were Cythera, Malta, and Eryx in Sicily from which she became known to the Romans as Venus Erycina. Three inscriptions from the Pyrgi Tablets dating to about 500 BC found near Caere in Etruria mentions the construction of a shrine to Astarte in the temple of the local goddess Uni-Astre (𐌔𐌄𐌓𐌕𐌔𐌀𐌋𐌀𐌉𐌍𐌖).[15][16] At Carthage Astarte was worshipped alongside the goddess Tanit, and frequently appeared as a theophoric element in personal names.[17]

The Aramean goddess Atargatis (Semitic form ʿAtarʿatah) may originally have been equated with Astarte, but developed its own distinct cult.

Iconography

Iconographic portrayal of Astarte, very similar to that of Tanit,[18] often depicts her naked and in presence of lions, identified respectively with symbols of sexuality and war. She is also depicted as winged, carrying the solar disk and the crescent moon as a headdress, and with her lions either lying prostrate to her feet or directly under those.[19] Aside from the lion, she's associated to the dove and the bee. She has also been associated with botanic wildlife like the palm tree and the lotus flower.[20]

A particular artistic motif assimilates Astarte to Europa, portraying her as riding a bull that would represent a partner deity. Similarly, after the popularization of her worship in Egypt, it was frequent to associate her with the war chariot of Ra or Horus, as well as a kind of weapon, the crescent axe.[19] Within Iberian culture, it has been proposed that native sculptures like those of Baza, Elche or Cerro de los Santos might represent an Iberized image of Astarte or Tanit.[20]

In Ugarit and Emar

Myths

In the Baʿal Epic of Ugarit, Ashtart is one of the allies of the eponymous hero. With the help of Anat she stops him from attacking the messengers who deliver the demands of Yam[21] and later assists him in the battle against the sea god, possibly "exhorting him to complete the task" during it.[22] It's a matter of academic debate if they were also viewed as consorts.[23] Their close relation is highlighted by the epithet "face of Baal" or "of the name of Baal."[24]

A different narrative, so-called "Myth of Astarte the huntress" casts Ashtart herself as the protagonist, and seemingly deals both with her role as a goddess of the hunt stalking game in the steppe, and with her possible relationship with Baal.[25]

Ashtart and Anat

Fragmentary narratives describe Ashtart and Anat hunting together. They were frequently treated as a pair in cult.[26] For example, an incantation against snakebite invokes them together in a list of gods who asked for help.[27] Texts from Emar, which are mostly of ritual nature unlike narrative ones known from Ugarit, indicate that Ashtart was a prominent deity in that city as well, and unlike in Ugarit, she additionally played a much bigger role in cult followings than Anat.[28]

Misconceptions in scholarship

While the association between Ashtart and Anat is well attested, primary sources from Ugarit and elsewhere provide no evidence in support of the misconception that Athirat (Asherah) and Ashtart were ever conflated, let alone that Athirat was ever viewed as Baal's consort like Ashtart possibly was. Scholar of Ugaritic mythology and the Bible Steve A. Wiggins in his monograph A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess notes that such arguments rest on scarce biblical evidence (which indicates at best a confusion between obscure terms in the Book of Judges[29] rather than between unrelated deities in Canaanite or Bronze Age Ugaritic religion) sums up the issue with such claims: "(...) Athtart begins with an ayin, and Athirat with an aleph. (...) Athtart appears in parallel with Anat in texts (...), but Athirat and Athtart do not occur in parallel."[30] God lists from Ugarit indicate that Ashtart was viewed as analogous to Mesopotamian Ishtar and Hurrian Ishara,[3] but not Athirat.

In Egypt

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Egyptian religion |

|---|

|

|

|

._From_Thebes%252C_Egypt._18th_Dynasty._The_Petrie_Museum_of_Egyptian_Archaeology%252C_London.jpg.webp)

Egyptian evidence is of particular importance as the only Bronze Age pictorial representations identified with absolute certainty as Astarte come from Egypt, rather than Ugarit, Emar or other Syrian cities, despite her prominence in religion attested in literature.[31]

Astarte arrived in ancient Egypt during the 18th dynasty along with other deities who were worshipped by northwest Semitic people, namely Anat, Baal (conflated with Set, who as a result started to be viewed as a heroic "foreign" god), Horon, Reshef and the enigmatic Qudshu. Due to her nature as a warrior goddess, often paired with Anat, Astarte was associated with warfare in Egyptian religion too, especially with horses and chariots. Due to the late arrival of these animals in Egypt, they weren't associated with any native deity prior to her introduction.[32]

Egyptian sources considered Astarte to be a daughter of the Memphite head god Ptah,[33] or of the sun god Ra.[34]

Association with Set

In the Contest Between Horus and Set, Astarte and Anat appear as daughters of Ra and are given as allies to the god Set, a reflection of their association with Baal. Some researchers perceive them as Set's wives as well, though much like the possibility of one or both of them being the wife of Baal in Ugarit this is uncertain.[35]

The so-called Astarte papyrus presents a myth similar to the Yam section of the Ugaritic Baal cycle or to certain episodes from the Hurro-Hittite Kumarbi cycle, but with Set, rather than Baal or Teshub, as the hero fighting the sea on behalf of the rest of the pantheon (in this case the Ennead, with Ptah singled out as its ruler). While discovered earlier than the Baal Cycle, in 1871, the myth didn't receive much attention until 1932 (e.g. after the discoveries in Ras Shamra).[36] The description of the battle itself isn't fully preserved (though references to it are scattered through other Egyptian texts, ex. Hearst papyrus), and as a result, Astarte appears as the most prominent figure in the surviving fragments, bringing tribute to the menacing sea god, identified as Yam much like in Ugaritic texts, to temporarily placate him. Her father Ptah and Renenutet, a harvest goddess, convince her to act as a tribute bearer. The text characterises her as a violent warrior goddess, in line with other Egyptian sources. Her role resembles that played by Shaushka in a number of Hurrian myths about combat with the sea.[37][38][39]

In Phoenicia

_01.jpg.webp)

Elizabeth Bloch-Smith in her overview of available evidence characterises the study of Astarte's role in Phoenician culture as lacking "methodological rigor."[40]

Mainland

In the hellenised description of the Phoenician pantheon ascribed to Sanchuniathon, Astarte appears as a daughter of Epigeius, "sky" (Ancient Greek: Οὐρανός ouranos/ Uranus; Roman god: Caelus) and Ge (Earth), and sister of the god Elus. After Elus overthrows and banishes his father Epigeius, as some kind of trick Epigeius sends Elus his "virgin daughter" Astarte along with her sisters Asherah and the goddess who will later be called Ba`alat Gebal, "the Lady of Byblos".[41] It seems that this trick does not work, as all three become wives of their brother Elus. Astarte bears Elus children who appear under Greek names as seven daughters called the Titanides or Artemides and two sons named Pothos "Longing" (as in πόθος, lit. 'lust') and Eros "Desire". Later with Elus' consent, Astarte and Adados reign over the land together. Astarte puts a bull's head on her own head to symbolize her sovereignty.[42] Wandering through the world, Astarte takes up a star that has fallen from the sky (a meteorite) and consecrates it at Tyre. As early as 1955 scholars pointed out that some elements from this account resemble the much earlier Baal Cycle from Ugarit, as well as the Hurrian Kumarbi cycle, namely the succession of generation after generation of gods, with a weather god as the final ruler.[43]

Religious studies scholar Jeffrey Burton Russell in his book The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity states that Astarte's most common symbol was the crescent moon (or horns).[44] Bull horns as a symbol of divinity are well attested in sources from ancient Levant, Mesopotamia and Anatolia. However the identification of Astarte with the moon - or rather with Selene - appears to have its origin in Lucian's De Dea Syria: the author compared "Astarte" worshiped in Sidon to the Greek goddess; his claims are contradicted by evidence known to modern archaeologists, which doesn't indicate any meaningful degree of Astarte worship in 2nd century Sidon (the goddess in mention might instead be unrelated Tanit).[45] Research of ancient Levantine and Syrian religion are far from certain if Astarte ever had an astral character herself, and her proposed astral symbol is Venus,[46] not the lunar crescent.

Small terracotta votives (Dea Gravida) are associated with Astarte by some researchers.[47] However, it is uncertain if these figures depict a goddess at all.[48]

Colonies and further spread in Hispania

Astarte was brought to Hispania by Phoenician merchants around the 8th century BC, after which she became possibly the most iconic goddess in the Iberian pantheon, being assimilated to native deities of similar attributes.[20] Her worship extended along the Mediterranean coast, where she had important centers in the cities of Gadir, Hispalis and Castulo, and it reached comparatively northern lands, among them Lusitanian and Carpetanian settlements in the modern Medellín and El Berrueco. The "Mount of Venus" mentioned in sources as a military emplacement by Lusitanian chieftain Viriathus, located behind the northern shore of the Tajo, has also been entertained to be a possible syncretic sanctuary of Astarte.[18]

Her worship was strengthened by the Carthaginian occupation that kickstarted the Second Punic War, bringing along the cult of its equivalent goddess Tanit, which was sometimes still referred to as Astarte as an archaistic trait.[20] It continued without opposition in the Roman Imperial period under the assimilated name of Dea Caelestis, dressed up with the attributes of the Roman goddesses Juno, Diana and Minerva.[18]

In the Bible

Ashtoreth is mentioned in the Hebrew Bible as a foreign, non-Judahite goddess, the principal goddess of the Sidonians (in biblical context a term analogous to "Phoenicians"). It is generally accepted that the Masoretic "vowel pointing" (adopted c. 7-10th centuries CE), indicating the pronunciation ʿAštōreṯ ("Ashtoreth," "Ashtoret") is a deliberate distortion of "Ashtart", and that this is probably because the two last syllables have been pointed with the vowels belonging to bōšeṯ, ("bosheth," abomination), to indicate that that word should be substituted when reading.[49] The plural form is pointed ʿAštārōṯ ("Ashtaroth"). The biblical Ashtoreth should not be confused with the goddess Asherah, the form of the names being quite distinct, and both appearing quite distinctly in the First Book of Kings. (In Biblical Hebrew, as in other older Semitic languages, Asherah begins with an aleph or glottal stop consonant א, while ʿAštōreṯ begins with an ʿayin or voiced pharyngeal consonant ע, indicating the lack of any plausible etymological connection between the two names.) Mark S. Smith suggested that the biblical writers may, however, have conflated some attributes and titles of the two, which according to him was a process that possibly occurred elsewhere throughout the 1st millennium BCE Levant.[50] However, Steve A. Wiggins found no clear evidence that Ashtart/Astarte was ever confused or conflated with Athirat.[51]

Ashteroth Karnaim was a city in the land of Bashan east of the Jordan River, mentioned in the Book of Genesis (Genesis 14:5) and the Book of Joshua (Joshua 12:4) (where it is rendered solely as Ashteroth). The name translates literally to 'Ashteroth of the Horns', with 'Ashteroth' being a Canaanite fertitility goddess and 'horns' being symbolic of mountain peaks. Figurines assumed to be Astarte by some researchers have been found at various archaeological sites in Israel.[52]

Later interpretations of biblical Astaroth

In some kabbalistic texts and in medieval and renaissance occultism (ex. The Book of Abramelin), the name Astaroth was assigned to a male demon bearing little resemblance to the figure known from antiquity. For the use of the Hebrew plural form ʿAštārōṯ in this sense, see Astaroth.

Other associations

Hittitologist Gary Beckman pointed out the similarity between Astarte's role as a goddess associated with horses and chariots to that played in Hittite religion by another "Ishtar type" goddess, Pinikir, introduced to Anatolia from Elam by Hurrians.[53]

Allat and Astarte may have been conflated in Palmyra. On one of the tesserae used by the Bel Yedi'ebel for a religious banquet at the temple of Bel, the deity Allat was given the name Astarte ('štrt). The assimilation of Allat to Astarte is not surprising in a milieu as much exposed to Aramaean and Phoenician influences as the one in which the Palmyrene theologians lived.[54]

Plutarch, in his On Isis and Osiris, indicates that the King and Queen of Byblos, who, unknowingly, have the body of Osiris in a pillar in their hall, are Melcarthus (i.e. Melqart) and Astarte (though he notes some instead call the Queen Saosis or Nemanūs, which Plutarch interprets as corresponding to the Greek name Athenais).[55]

Lucian of Samosata asserts that in the territory of Sidon the temple of Astarte was sacred to Europa.[56] In Greek mythology Europa was a Phoenician princess whom Zeus, having transformed himself into a white bull, abducted, and carried to Crete.

Byron used the name Astarte in his poem Manfred.

Fringe publications

Hans Georg Wunderlich speculated that the cult of a Minoan goddess as Aphrodite developed from Astarte and was transmitted to Cythera and then to Greece.[57] While it is accepted among many Hellenic scholars that Aphrodite may have originated or been influenced by Astarte,[58] Winderlich's contribution is of little value as he was not a historian but a geologist, and his book about Crete "cannot be taken seriously" and "manipulated the evidence" according to experts; its core theme is a pseudohistorical claim that the Minoan palaces served as tombs for enormous numbers of mummies, which contradicts archaeological evidence.[59]

Wunderlich related the Minoan snake goddess with Astarte, claiming that her worship was connected with an orgiastic cult while her temples were decorated with serpentine motifs.[60] Snakes weren't among the symbols of Ashtart/Athtart used by contemporaries of the Minoans,[61] while the very notion of a Minoan "snake goddess" is a controversial concept, as the restoration of the figures is regarded as flawed by modern authors,[62] and the idea became entrenched in public perception to a large degree because of early forgeries created in the wake of early 20th century excavations.[63] Additionally nowhere in other known Minoan art does a similar motif appear.[64]

There is some evidence of foreign influences being a factor in Minoan religious life, but mostly for Egyptian motifs like the Minoan genius.[65]

In popular culture

- The name Astarte was given to a massive post-starburst galaxy during the cosmic noon (the peak of the star formation rate density).[66]

- Astarte appears as a playable Avenger-class Servant in Fate/Grand Order (2015), with her name stylized as "Ashtart". However, she first introduces herself as "Space Ishtar", and only reveals her true name after her third Ascension.

See also

- Aicha Kandicha

- Anat

- Attar (god)

- Ishtar

- Ishara

- Nanaya

- Nana (Kushan goddess)

- Star of Ishtar

- Tanit

- Venus

References

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 48-49; 61

- T. J. Lewis, ʿAthtartu’s Incantations and the Use of Divine Names as Weapons, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 71, 2011, p. 208

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 74-75

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 76-77

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 33-34; 36

- K. van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter Willem van der Horst, Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, p. 109-10.

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 45; 54

- R. Schmitt, Astarte, Mistress of Horses, Lady of the Chariot: The Warrior Aspect of Astarte, Die Welt des Orients 43, 2013, p. 213-225

- I. Cornelius, “Revisiting” Astarte in the Iconography of the Bronze Age Levant [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 91

- I. Cornelius, “Revisiting” Astarte in the Iconography of the Bronze Age Levant [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 92-93; 95

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p.35

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 36; 74-77

- Budin, Stephanie L. (2004). "A Reconsideration of the Aphrodite-Ashtart Syncretism". Numen. 51 (2): 95–145. doi:10.1163/156852704323056643.

- (Snaith, The Interpreter's Bible, 1954, Vol. 3, p. 103)

- Paolo Agostini and Adolfo Zavaroni, “The Bilingual Phoenician-Etruscan Text of the Golden Plates of Pyrgi,” Filologica 34 (2000)

- E. Bloch-Smith, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence for Phoenician Astarte [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 186

- E. Bloch-Smith, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence for Phoenician Astarte [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 185-186

- Manuel Salinas de Frías, El Afrodísion Óros de Viriato, Acta Palaeohispanica XI. Palaeohispanica 13 (2013), pp. 257-271 I.S.S.N.: 1578-5386.

- María Cruz Martín Ceballos, Diosas y leones en el período orientalizante de la Península Ibérica, SPAL 11 (2002): 169-195

- Ana María Vázquez Hoys, En manos de Astarté, la Abrasadora, revista Aldaba, Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia, ISSN 0213-7925, Nº. 30, 1998

- S. A. Wiggins, A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess, 2007, p. 43

- T. J. Lewis, ʿAthtartu’s Incantations and the Use of Divine Names as Weapons, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 71, 2011, p. 210

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 59-60

- discussed in detail in T. J. Lewis, ʿAthtartu’s Incantations and the Use of Divine Names as Weapons, Journal of Near Eastern Studies 71, 2011

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 48-49

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 49-51

- G. Del Olme Lete, KTU 1.107: A miscellany of incantations against snakebite [in] O. Loretz, S. Ribichini, W. G. E. Watson, J. Á. Zamora (eds), Ritual, Religion and Reason. Studies in the Ancient World in Honour of Paolo Xella, 2013, p. 198

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p.34

- S. A. Wiggins, A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess, 2007, p. 117

- S. A. Wiggins, A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess, 2007, p. 57, footnote 124; see also p. 169

- I. Cornelius, “Revisiting” Astarte in the Iconography of the Bronze Age Levant [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 88

- K. Tazawa, Astarte in New Kingdom Egypt: Reconsideration of Her Role and Function [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 103-104

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 66

- K. Tazawa, Astarte in New Kingdom Egypt: Reconsideration of Her Role and Function [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 110

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 60-61

- M. Dijkstra, Ishtar seduces the Sea-serpent. A New Join in the Epic of Hedammu (KUB 36, 56+95) and its meaning for the battle between Baal and Yam in Ugaritic Tradition, Ugarit-Forschungen 43, 2011, p. 54

- N. Ayali-Darshan, The Other Version of the Story of the Storm-god’s Combat with the Sea in the Light of Egyptian, Ugaritic, and Hurro-Hittite Texts, Journal of Ancient Near Eastern Religions 15, 2015, p. 32-35

- M. Dijkstra, Ishtar seduces the Sea-serpent. A New Join in the Epic of Hedammu (KUB 36, 56+95) and its meaning for the battle between Baal and Yam in Ugaritic Tradition, Ugarit-Forschungen 43, 2011, p. 57-59

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 66-68

- E. Bloch-Smith, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence for Phoenician Astarte [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 167

- Je m'appelle Byblos, Jean-Pierre Thiollet, H & D, 2005, p. 73. ISBN 2 914 266 04 9

- E. Bloch-Smith, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence for Phoenician Astarte [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 170

- M. H. Pope, El in the Ugaritic texts, 1955, p. 56-57

- Jeffrey Burton Russell. The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity. (Cornell University Press 1977). ISBN 0-8014-9409-5 p. 94.

- E. Bloch-Smith, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence for Phoenician Astarte [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 184: "De Dea Syria 4 refers to “another great sanctuary in Phoenicia, which the Sidonians possess. According to them, it belongs to Astarte, but I think that Astarte is Selene.”"

- M. Smith, ‘Athtart in Late Bronze Age Syrian Texts [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 35

- Markoe, Glenn (2000-01-01). Phoenicians. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0520226142.

- E. Bloch-Smith, Archaeological and Inscriptional Evidence for Phoenician Astarte [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014, p. 193: "The clothed, pregnant figurines may be votive items rather than deities, representing prayers for a fruitful pregnancy modeled in the round."

- Day, John (2002-12-01). John Day, "Yahweh and the gods and goddesses of Canaan", p.128. ISBN 9780826468307. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- Smith, Mark S. (2002-08-03). Mark S. Smith, "The early history of God", p.129. ISBN 9780802839725. Retrieved 2014-04-25.

- S. A. Wiggins, A Reassessment of Asherah: With Further Considerations of the Goddess, 2007, p. 169

- Raphael Patai. The Hebrew Goddess. (Wayne State University Press 1990). ISBN 0-8143-2271-9 p. 57.

- G. Beckman, The Goddess Pirinkir and Her Ritual from Hattusa (CTH 644), KTEMA 24, 1999, p. 39

- Teixidor, Javier (1979). The Pantheon of Palmyra. Brill Archive. ISBN 978-90-04-05987-0.

- Griffiths, J. Gwyn, Plutarch's De Iside et Osiride, pp. 325–327

- Lucian of Samosata. De Dea Syria.

- H. G. Wunderlich. The Secret of Creta. Efstathiadis Group. Athens 1987. p. 134.

- Breitenberger, Barbara (2013-05-13). Aphrodite and Eros: The Development of Greek Erotic Mythology. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-88377-5.

- K. Branigan, The Secret of Crete by Hans Georg Wunderlich, Richard Winston (review), The Geographical Journal 3 (144), 1978, p. 502-503

- Wunderlich, H.G. (1994) [1975]. The Secret of Crete. Efstathiadis group S.A. pp. 260, 276. ISBN 960-226-261-3. (First British edition, published 1975 by Souvenir Press Ltd., London.)

- see I. Cornelius, “Revisiting” Astarte in the Iconography of the Bronze Age Levant [in:] D. T. Sugimoto (ed), Transformation of a Goddess. Ishtar – Astarte – Aphrodite, 2014 for a detailed overview of relevant symbols

- C. Eller, Two Knights and a Goddess: Sir Arthur Evans, Sir James George Frazer, and the Invention of Minoan Religion, Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 25.1, 2012, p. 82-83

- C. Eller, Two Knights and a Goddess: Sir Arthur Evans, Sir James George Frazer, and the Invention of Minoan Religion, Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 25.1, 2012, p. 93-94

- N. Marinatos, Minoan religion. Ritual, image and symbol, 1993, p. 148: "It is true, of course, that the pieces of Minoan art that one is not apt to forget are the snake goddesses from the palace of Knossos (...). What is not often stressed is that the two faience figures are the only examples associated with snakes from the entire palace period; even in Prepalatial times, there is no snake goddess."

- discussed ex. in V. Dubcová, Divine power from abroad. Some new thoughts about the foreign influences on the Aegean Bronze Age religious iconography [in:] E. Alram-Stern, F. Blakolmer, S. Deger-Jalkotzy, R. Laffineur & J. Weilhartner (eds), Metaphysis. Ritual, Myth and Symbolism in the Aegean Bronze Age, 2016, p. 263-273

- Hamed, M. (2021). "Multiwavelength dissection of a massive heavily dust-obscured galaxy and its blue companion at z∼2". Astronomy & Astrophysics. 646: A127. arXiv:2101.07724. Bibcode:2021A&A...646A.127H. doi:10.1051/0004-6361/202039577. S2CID 231639096.

Further reading

- Daressy, Georges (1905). Statues de Divinités, (CGC 38001-39384). Vol. II. Cairo: Imprimerie de l'Institut français d'archéologie orientale.

- Scherm, Gerd; Tast, Brigitte (1996). Astarte und Venus. Eine foto-lyrische Annäherung. Schellerten. ISBN 3-88842-603-0.

- Harden, Donald (1980). The Phoenicians (2nd ed.). London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-021375-9.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger. "Astarte, Mistress of Horses, Lady of the Chariot: The Warrior Aspect of Astarte." Die Welt Des Orients 43, no. 2 (2013): 213–25. Accessed June 28, 2020. www.jstor.org/stable/23608856.

- Sugimoto, David T., ed. (2014). Transformation of a Goddess: Ishtar, Astarte, Aphrodite. Academic Press Fribourg / Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Göttingen. ISBN 978-3-7278-1748-9. / ISBN 978-3-525-54388-7