Digital audio

Digital audio is a representation of sound recorded in, or converted into, digital form. In digital audio, the sound wave of the audio signal is typically encoded as numerical samples in a continuous sequence. For example, in CD audio, samples are taken 44,100 times per second, each with 16-bit sample depth. Digital audio is also the name for the entire technology of sound recording and reproduction using audio signals that have been encoded in digital form. Following significant advances in digital audio technology during the 1970s and 1980s, it gradually replaced analog audio technology in many areas of audio engineering, record production and telecommunications in the 1990s and 2000s

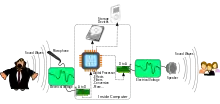

In a digital audio system, an analog electrical signal representing the sound is converted with an analog-to-digital converter (ADC) into a digital signal, typically using pulse-code modulation (PCM). This digital signal can then be recorded, edited, modified, and copied using computers, audio playback machines, and other digital tools. For playback a digital-to-analog converter (DAC) performs the reverse process, converting a digital signal back into an analog signal, which is then sent through an audio power amplifier and ultimately to a loudspeaker.

Digital audio systems may include compression, storage, processing, and transmission components. Conversion to a digital format allows convenient manipulation, storage, transmission, and retrieval of an audio signal. Unlike analog audio, in which making copies of a recording results in generation loss and degradation of signal quality, digital audio allows an infinite number of copies to be made without any degradation of signal quality.

Overview

Digital audio technologies are used in the recording, manipulation, mass-production, and distribution of sound, including recordings of songs, instrumental pieces, podcasts, sound effects, and other sounds. Modern online music distribution depends on digital recording and data compression. The availability of music as data files, rather than as physical objects, has significantly reduced the costs of distribution as well as made it easier to share copies.[1] Before digital audio, the music industry distributed and sold music by selling physical copies in the form of records and cassette tapes. With digital-audio and online distribution systems such as iTunes, companies sell digital sound files to consumers, which the consumer receives over the Internet. Popular streaming services such as Spotify and Youtube, offer temporary access to the digital file, and are now the most common form of music consumption[2]

An analog audio system converts physical waveforms of sound into electrical representations of those waveforms by use of a transducer, such as a microphone. The sounds are then stored on an analog medium such as magnetic tape, or transmitted through an analog medium such as a telephone line or radio. The process is reversed for reproduction: the electrical audio signal is amplified and then converted back into physical waveforms via a loudspeaker. Analog audio retains its fundamental wave-like characteristics throughout its storage, transformation, duplication, and amplification.

Analog audio signals are susceptible to noise and distortion, due to the innate characteristics of electronic circuits and associated devices. Disturbances in a digital system do not result in error unless they are so large as to result in a symbol being misinterpreted as another symbol or disturb the sequence of symbols. It is therefore generally possible to have an entirely error-free digital audio system in which no noise or distortion is introduced between conversion to digital format and conversion back to analog.

A digital audio signal may be encoded for correction of any errors that might occur in the storage or transmission of the signal. This technique, known as channel coding, is essential for broadcast or recorded digital systems to maintain bit accuracy. Eight-to-fourteen modulation is the channel code used for the audio compact disc (CD).

Conversion process

If an audio signal is analog, a digital audio system starts with an ADC that converts an analog signal to a digital signal.[note 1] The ADC runs at a specified sampling rate and converts at a known bit resolution. CD audio, for example, has a sampling rate of 44.1 kHz (44,100 samples per second), and has 16-bit resolution for each stereo channel. Analog signals that have not already been bandlimited must be passed through an anti-aliasing filter before conversion, to prevent the aliasing distortion that is caused by audio signals with frequencies higher than the Nyquist frequency (half the sampling rate).

A digital audio signal may be stored or transmitted. Digital audio can be stored on a CD, a digital audio player, a hard drive, a USB flash drive, or any other digital data storage device. The digital signal may be altered through digital signal processing, where it may be filtered or have effects applied. Sample-rate conversion including upsampling and downsampling may be used to change signals that have been encoded with a different sampling rate to a common sampling rate prior to processing. Audio data compression techniques, such as MP3, Advanced Audio Coding, Ogg Vorbis, or FLAC, are commonly employed to reduce the file size. Digital audio can be carried over digital audio interfaces such as AES3 or MADI. Digital audio can be carried over a network using audio over Ethernet, audio over IP or other streaming media standards and systems.

For playback, digital audio must be converted back to an analog signal with a DAC. According to the Nyquist–Shannon sampling theorem, with some practical and theoretical restrictions, a band-limited version of the original analog signal can be accurately reconstructed from the digital signal.

History

Coding

Pulse-code modulation (PCM) was invented by British scientist Alec Reeves in 1937.[3] In 1950, C. Chapin Cutler of Bell Labs filed the patent on differential pulse-code modulation (DPCM),[4] a data compression algorithm. Adaptive DPCM (ADPCM) was introduced by P. Cummiskey, Nikil S. Jayant and James L. Flanagan at Bell Labs in 1973.[5][6]

Perceptual coding was first used for speech coding compression, with linear predictive coding (LPC).[7] Initial concepts for LPC date back to the work of Fumitada Itakura (Nagoya University) and Shuzo Saito (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone) in 1966.[8] During the 1970s, Bishnu S. Atal and Manfred R. Schroeder at Bell Labs developed a form of LPC called adaptive predictive coding (APC), a perceptual coding algorithm that exploited the masking properties of the human ear, followed in the early 1980s with the code-excited linear prediction (CELP) algorithm.[7]

Discrete cosine transform (DCT) coding, a lossy compression method first proposed by Nasir Ahmed in 1972,[9][10] provided the basis for the modified discrete cosine transform (MDCT), which was developed by J. P. Princen, A. W. Johnson and A. B. Bradley in 1987.[11] The MDCT is the basis for most audio coding standards, such as Dolby Digital (AC-3),[12] MP3 (MPEG Layer III),[13][7] Advanced Audio Coding (AAC), Windows Media Audio (WMA), and Vorbis (Ogg).[12]

Recording

PCM was used in telecommunications applications long before its first use in commercial broadcast and recording. Commercial digital recording was pioneered in Japan by NHK and Nippon Columbia and their Denon brand, in the 1960s. The first commercial digital recordings were released in 1971.[14]

The BBC also began to experiment with digital audio in the 1960s. By the early 1970s, it had developed a 2-channel recorder, and in 1972 it deployed a digital audio transmission system that linked their broadcast center to their remote transmitters.[14]

The first 16-bit PCM recording in the United States was made by Thomas Stockham at the Santa Fe Opera in 1976, on a Soundstream recorder. An improved version of the Soundstream system was used to produce several classical recordings by Telarc in 1978. The 3M digital multitrack recorder in development at the time was based on BBC technology. The first all-digital album recorded on this machine was Ry Cooder's Bop till You Drop in 1979. British record label Decca began development of its own 2-track digital audio recorders in 1978 and released the first European digital recording in 1979.[14]

Popular professional digital multitrack recorders produced by Sony/Studer (DASH) and Mitsubishi (ProDigi) in the early 1980s helped to bring about digital recording's acceptance by the major record companies. Machines for these formats had their own transports built-in as well, using reel-to-reel tape in either 1/4", 1/2", or 1" widths, with the audio data being recorded to the tape using a multi-track stationary tape head. PCM adaptors allowed for stereo digital audio recording on a conventional NTCS or PAL video tape recorder.

The 1982 introduction of the CD popularized digital audio with consumers.[14]

ADAT became available in the early 1990s, which allowed eight-track 44.1 or 48 kHz recording on S-VHS cassettes, and DTRS performed a similar function with Hi8 tapes.

Formats like ProDigi and DASH were referred to as SDAT (Stationary-head Digital Audio Tape) formats, as opposed to formats like the PCM adaptor-based systems and DAT, which were referred to as RDAT (Rotating-head Digital Audio Tape) formats, due to their helical-scan process of recording.

Like the DAT cassette, ProDigi and DASH machines also accommodated the obligatory 44.1 kHz sampling rate, but also 48 kHz on all machines, and eventually a 96 kHz sampling rate. They overcame the problems that made typical analog recorders unable to meet the bandwidth (frequency range) demands of digital recording by a combination of higher tape speeds, narrower head gaps used in combination with metal-formulation tapes, and the spreading of data across multiple parallel tracks.

Unlike Analog systems, modern Digital audio workstations and audio interfaces allow as many channels in as many different sampling rates as the computer can effectively run at a single time. This makes multitrack recording and mixing much easier for large projects which would otherwise be difficult with analog gear.

Telephony

The rapid development and wide adoption of PCM digital telephony was enabled by metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) switched capacitor (SC) circuit technology, developed in the early 1970s.[15] This led to the development of PCM codec-filter chips in the late 1970s.[15][16] The silicon-gate CMOS (complementary MOS) PCM codec-filter chip, developed by David A. Hodges and W.C. Black in 1980,[15] has since been the industry standard for digital telephony.[15][16] By the 1990s, telecommunication networks such as the public switched telephone network (PSTN) had been largely digitized with VLSI (very large-scale integration) CMOS PCM codec-filters, widely used in electronic switching systems for telephone exchanges, user-end modems and a range of digital transmission applications such as the integrated services digital network (ISDN), cordless telephones and cell phones.[16]

Technologies

Digital audio is used in broadcasting of audio. Standard technologies include Digital audio broadcasting (DAB), Digital Radio Mondiale (DRM), HD Radio and In-band on-channel (IBOC).

Digital audio in recording applications is stored on audio-specific technologies including CD, Digital Audio Tape (DAT), Digital Compact Cassette (DCC) and MiniDisc. Digital audio may be stored in a standard audio file formats and stored on a Hard disk recorder, Blu-ray or DVD-Audio. Files may be played back on smartphones, computers or MP3 player. Digital audio resolution is measured in sample depth. Most digital audio formats use a sample depth of either 16-bit, 24-bit, and 32-bit.

Interfaces

.jpg.webp)

Digital-audio-specific interfaces include:

- A2DP via Bluetooth

- AC'97 (Audio Codec 1997) interface between integrated circuits on PC motherboards

- ADAT Lightpipe interface

- AES3 interface with XLR connectors, common in professional audio equipment

- AES47 - professional AES3-style digital audio over Asynchronous Transfer Mode networks

- Intel High Definition Audio - modern replacement for AC'97

- I²S (Inter-IC sound) interface between integrated circuits in consumer electronics

- MADI (Multichannel Audio Digital Interface)

- MIDI - low-bandwidth interconnect for carrying instrument data; cannot carry sound but can carry digital sample data in non-realtime

- S/PDIF - either over coaxial cable or TOSLINK, common in consumer audio equipment and derived from AES3

- TDIF, TASCAM proprietary format with D-sub cable

Several interfaces are engineered to carry digital video and audio together, including HDMI and DisplayPort. Some interfaces offer MIDI support as well as XLR and TRS analog ports.

For personal computers, USB and IEEE 1394 have provisions to deliver real-time digital audio. USB interfaces have become increasingly popular among independent audio engineers and producers due to their small size and ease of use. In professional architectural or installation applications, many audio over Ethernet protocols and interfaces exist. In broadcasting, a more general audio over IP network technology is favored. In telephony voice over IP is used as a network interface for digital audio for voice communications.

See also

- Digital audio editor

- Digital synthesizer

- Frequency modulation synthesis

- Sound chip

- Sound Card

- Audio Interface

- Quantization

- Sampling

- Multitrack recording

- Digital audio workstation

Notes

- Some audio signals such as those created by digital synthesis originate entirely in the digital domain, in which case analog to digital conversion does not take place.

References

- Janssens, Jelle; Stijn Vandaele; Tom Vander Beken (2009). "The Music Industry on (the) Line? Surviving Music Piracy in a Digital Era". European Journal of Crime, Criminal Law and Criminal Justice. 77 (96): 77–96. doi:10.1163/157181709X429105. hdl:1854/LU-608677.

- Liikkanen, Lassi A.; Åman, Pirkka (May 2016). "Shuffling Services: Current Trends in Interacting with Digital Music". Interacting with Computers. 28 (3): 352–371. doi:10.1093/iwc/iwv004. ISSN 0953-5438.

- Genius Unrecognised, BBC, 2011-03-27, retrieved 2011-03-30

- US patent 2605361, C. Chapin Cutler, "Differential Quantization of Communication Signals", issued 1952-07-29

- P. Cummiskey, Nikil S. Jayant, and J. L. Flanagan, "Adaptive quantization in differential PCM coding of speech", Bell Syst. Tech. J., vol. 52, pp. 1105—1118, Sept. 1973

- Cummiskey, P.; Jayant, Nikil S.; Flanagan, J. L. (1973). "Adaptive quantization in differential PCM coding of speech". The Bell System Technical Journal. 52 (7): 1105–1118. doi:10.1002/j.1538-7305.1973.tb02007.x. ISSN 0005-8580.

- Schroeder, Manfred R. (2014). "Bell Laboratories". Acoustics, Information, and Communication: Memorial Volume in Honor of Manfred R. Schroeder. Springer. p. 388. ISBN 9783319056609.

- Gray, Robert M. (2010). "A History of Realtime Digital Speech on Packet Networks: Part II of Linear Predictive Coding and the Internet Protocol" (PDF). Found. Trends Signal Process. 3 (4): 203–303. doi:10.1561/2000000036. ISSN 1932-8346.

- Ahmed, Nasir (January 1991). "How I Came Up With the Discrete Cosine Transform". Digital Signal Processing. 1 (1): 4–5. doi:10.1016/1051-2004(91)90086-Z.

- Nasir Ahmed; T. Natarajan; Kamisetty Ramamohan Rao (January 1974). "Discrete Cosine Transform" (PDF). IEEE Transactions on Computers. C-23 (1): 90–93. doi:10.1109/T-C.1974.223784. S2CID 149806273.

- J. P. Princen, A. W. Johnson und A. B. Bradley: Subband/transform coding using filter bank designs based on time domain aliasing cancellation, IEEE Proc. Intl. Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing (ICASSP), 2161–2164, 1987.

- Luo, Fa-Long (2008). Mobile Multimedia Broadcasting Standards: Technology and Practice. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 590. ISBN 9780387782638.

- Guckert, John (Spring 2012). "The Use of FFT and MDCT in MP3 Audio Compression" (PDF). University of Utah. Retrieved 14 July 2019.

- Fine, Thomas (2008). Barry R. Ashpole (ed.). "The Dawn of Commercial Digital Recording" (PDF). ARSC Journal. Retrieved 2010-05-02.

- Allstot, David J. (2016). "Switched Capacitor Filters" (PDF). In Maloberti, Franco; Davies, Anthony C. (eds.). A Short History of Circuits and Systems: From Green, Mobile, Pervasive Networking to Big Data Computing. IEEE Circuits and Systems Society. pp. 105–110. ISBN 9788793609860. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-09-30. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- Floyd, Michael D.; Hillman, Garth D. (8 October 2018) [1st pub. 2000]. "Pulse-Code Modulation Codec-Filters". The Communications Handbook (2nd ed.). CRC Press. pp. 26–1, 26–2, 26–3. ISBN 9781420041163.

Further reading

- Borwick, John, ed., 1994: Sound Recording Practice (Oxford: Oxford University Press)

- Bosi, Marina, and Goldberg, Richard E., 2003: Introduction to Digital Audio Coding and Standards (Springer)

- Ifeachor, Emmanuel C., and Jervis, Barrie W., 2002: Digital Signal Processing: A Practical Approach (Harlow, England: Pearson Education Limited)

- Rabiner, Lawrence R., and Gold, Bernard, 1975: Theory and Application of Digital Signal Processing (Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc.)

- Watkinson, John, 1994: The Art of Digital Audio (Oxford: Focal Press)

External links

- Monty Montgomery (2012-10-24). "Guest Opinion: Why 24/192 Music Downloads Make No Sense". evolver.fm. Archived from the original on 2012-12-10. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- J. ROBERT STUART. "Coding High Quality Digital Audio" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-27. Retrieved 2012-12-07.

- Dan Lavry. "Sampling Theory For Digital Audio" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-12-07.