Automated teller machine

An automated teller machine (ATM) or cash machine (in British English) is an electronic telecommunications device that enables customers of financial institutions to perform financial transactions, such as cash withdrawals, deposits, funds transfers, balance inquiries or account information inquiries, at any time and without the need for direct interaction with bank staff.

| Part of a series on financial services |

| Banking |

|---|

|

.jpg.webp)

ATMs are known by a variety of names, including automatic teller machine (ATM) in the United States[1][2][3] (sometimes redundantly as "ATM machine"). In Canada, the term automated banking machine (ABM) is also used,[4][5] although ATM is also very commonly used in Canada, with many Canadian organizations using ATM over ABM.[6][7][8] In British English, the terms cashpoint, cash machine and hole in the wall are most widely used.[9] Other terms include any time money, cashline, tyme machine, cash dispenser, cash corner, bankomat, or bancomat. ATMs that are not operated by a financial institution are known as "white-label" ATMs.

Using an ATM, customers can access their bank deposit or credit accounts in order to make a variety of financial transactions, most notably cash withdrawals and balance checking, as well as transferring credit to and from mobile phones. ATMs can also be used to withdraw cash in a foreign country. If the currency being withdrawn from the ATM is different from that in which the bank account is denominated, the money will be converted at the financial institution's exchange rate.[10] Customers are typically identified by inserting a plastic ATM card (or some other acceptable payment card) into the ATM, with authentication being by the customer entering a personal identification number (PIN), which must match the PIN stored in the chip on the card (if the card is so equipped), or in the issuing financial institution's database.

According to the ATM Industry Association (ATMIA), as of 2015, there were close to 3.5 million ATMs installed worldwide.[11][12] However, the use of ATMs is gradually declining with the increase in cashless payment systems.[13]

History

The idea of out-of-hours cash distribution developed from bankers' needs in Japan, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.[14][15][16]

In 1960 Luther George Simjian invented an automated deposit machine (accepting coins, cash and cheques) although it did not have cash dispensing features.[17] His US patent was first filed on 30 June 1960 and granted on 26 February 1963.[18] The roll-out of this machine, called Bankograph, was delayed by a couple of years, due in part to Simjian's Reflectone Electronics Inc. being acquired by Universal Match Corporation.[19] An experimental Bankograph was installed in New York City in 1961 by the City Bank of New York, but removed after six months due to the lack of customer acceptance.[20]

In 1962 Adrian Ashfield invented the idea of a card system to securely identify a user and control and monitor the dispensing of goods or services. This was granted UK Patent 959,713 in June 1964 and assigned to Kins Developments Limited.[21]

A Japanese device called the "Computer Loan Machine" supplied cash as a three-month loan at 5% p.a. after inserting a credit card. The device was operational in 1966.[22][23] However, little is known about the device.[14]

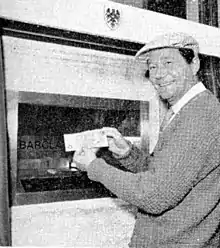

A cash machine was put into use by Barclays Bank in its Enfield Town branch in North London, United Kingdom, on 27 June 1967.[24] This machine was inaugurated by English comedy actor Reg Varney.[25] This instance of the invention is credited to the engineering team led by John Shepherd-Barron of printing firm De La Rue,[26] who was awarded an OBE in the 2005 New Year Honours.[27][28] Transactions were initiated by inserting paper cheques issued by a teller or cashier, marked with carbon-14 for machine readability and security, which in a later model were matched with a four-digit personal identification number (PIN).[26][29] Shepherd-Barron stated "It struck me there must be a way I could get my own money, anywhere in the world or the UK. I hit upon the idea of a chocolate bar dispenser, but replacing chocolate with cash."[26]

The Barclays–De La Rue machine (called De La Rue Automatic Cash System or DACS)[30] beat the Swedish saving banks' and a company called Metior's machine (a device called Bankomat) by a mere nine days and Westminster Bank's–Smith Industries–Chubb system (called Chubb MD2) by a month.[31] The online version of the Swedish machine is listed to have been operational on 6 May 1968, while claiming to be the first online ATM in the world, ahead of similar claims by IBM and Lloyds Bank in 1971,[32] and Oki in 1970.[33] The collaboration of a small start-up called Speytec and Midland Bank developed a fourth machine which was marketed after 1969 in Europe and the US by the Burroughs Corporation. The patent for this device (GB1329964) was filed in September 1969 (and granted in 1973) by John David Edwards, Leonard Perkins, John Henry Donald, Peter Lee Chappell, Sean Benjamin Newcombe, and Malcom David Roe.

Both the DACS and MD2 accepted only a single-use token or voucher which was retained by the machine, while the Speytec worked with a card with a magnetic stripe at the back. They used principles including Carbon-14 and low-coercivity magnetism in order to make fraud more difficult.

The idea of a PIN stored on the card was developed by a group of engineers working at Smiths Group on the Chubb MD2 in 1965 and which has been credited to James Goodfellow[34] (patent GB1197183 filed on 2 May 1966 with Anthony Davies). The essence of this system was that it enabled the verification of the customer with the debited account without human intervention. This patent is also the earliest instance of a complete "currency dispenser system" in the patent record. This patent was filed on 5 March 1968 in the US (US 3543904) and granted on 1 December 1970. It had a profound influence on the industry as a whole. Not only did future entrants into the cash dispenser market such as NCR Corporation and IBM licence Goodfellow's PIN system, but a number of later patents reference this patent as "Prior Art Device".[35]

Propagation

Devices designed by British (i.e. Chubb, De La Rue) and Swedish (i.e. Asea Meteor) quickly spread out. For example, given its link with Barclays, Bank of Scotland deployed a DACS in 1968 under the 'Scotcash' brand. Customers were given personal code numbers to activate the machines, similar to the modern PIN. They were also supplied with £10 vouchers. These were fed into the machine, and the corresponding amount debited from the customer's account.

A Chubb-made ATM appeared in Sydney in 1969. This was the first ATM installed in Australia. The machine only dispensed $25 at a time and the bank card itself would be mailed to the user after the bank had processed the withdrawal.

Asea Metior's Bancomat was the first ATM installed in Spain on 9 January 1969, in central Madrid by Banesto. This device dispensed 1,000 peseta bills (1 to 5 max). Each user had to introduce a security personal key using a combination of the ten numeric buttons.[36] In March of the same year an ad with the instructions to use the Bancomat was published in the same newspaper.[37]

Docutel in the United States

After looking firsthand at the experiences in Europe, in 1968 the ATM was pioneered in the U.S. by Donald Wetzel, who was a department head at a company called Docutel.[28] Docutel was a subsidiary of Recognition Equipment Inc of Dallas, Texas, which was producing optical scanning equipment and had instructed Docutel to explore automated baggage handling and automated gasoline pumps.[38]

On 2 September 1969, Chemical Bank installed a prototype ATM in the U.S. at its branch in Rockville Centre, New York. The first ATMs were designed to dispense a fixed amount of cash when a user inserted a specially coded card.[39] A Chemical Bank advertisement boasted "On Sept. 2 our bank will open at 9:00 and never close again."[40] Chemical's ATM, initially known as a Docuteller was designed by Donald Wetzel and his company Docutel. Chemical executives were initially hesitant about the electronic banking transition given the high cost of the early machines. Additionally, executives were concerned that customers would resist having machines handling their money.[41] In 1995, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History recognised Docutel and Wetzel as the inventors of the networked ATM.[42] To show confidence in Docutel, Chemical installed the first four production machines in a marketing test that proved they worked reliably, customers would use them and even pay a fee for usage. Based on this, banks around the country began to experiment with ATM installations.

By 1974, Docutel had acquired 70 percent of the U.S. market; but as a result of the early 1970s worldwide recession and its reliance on a single product line, Docutel lost its independence and was forced to merge with the U.S. subsidiary of Olivetti.

In 1973, Wetzel was granted U.S. Patent # 3,761,682; the application had been filed in October 1971. However, the U.S. patent record cites at least three previous applications from Docutel, all relevant to the development of the ATM and where Wetzel does not figure, namely US Patent # 3,662,343, U.S. Patent # 3651976 and U.S. Patent # 3,68,569. These patents are all credited to Kenneth S. Goldstein, MR Karecki, TR Barnes, GR Chastian and John D. White.

Further advances

In April 1971, Busicom began to manufacture ATMs based on the first commercial microprocessor, the Intel 4004. Busicom manufactured these microprocessor-based automated teller machines for several buyers, with NCR Corporation as the main customer.[43]

Mohamed Atalla invented the first hardware security module (HSM),[44] dubbed the "Atalla Box", a security system which encrypted PIN and ATM messages, and protected offline devices with an un-guessable PIN-generating key.[45] In March 1972, Atalla filed U.S. Patent 3,938,091 for his PIN verification system, which included an encoded card reader and described a system that utilized encryption techniques to assure telephone link security while entering personal ID information that was transmitted to a remote location for verification.[46]

He founded Atalla Corporation (now Utimaco Atalla) in 1972,[47] and commercially launched the "Atalla Box" in 1973.[45] The product was released as the Identikey. It was a card reader and customer identification system, providing a terminal with plastic card and PIN capabilities. The Identikey system consisted of a card reader console, two customer PIN pads, intelligent controller and built-in electronic interface package.[48] The device consisted of two keypads, one for the customer and one for the teller. It allowed the customer to type in a secret code, which is transformed by the device, using a microprocessor, into another code for the teller.[49] During a transaction, the customer's account number was read by the card reader. This process replaced manual entry and avoided possible key stroke errors. It allowed users to replace traditional customer verification methods such as signature verification and test questions with a secure PIN system.[48] The success of the "Atalla Box" led to the wide adoption of hardware security modules in ATMs.[50] Its PIN verification process was similar to the later IBM 3624.[51] Atalla's HSM products protect 250 million card transactions every day as of 2013,[47] and secure the majority of the world's ATM transactions as of 2014.[44]

The IBM 2984 was a modern ATM and came into use at Lloyds Bank, High Street, Brentwood, Essex, the UK in December 1972. The IBM 2984 was designed at the request of Lloyds Bank. The 2984 Cash Issuing Terminal was a true ATM, similar in function to today's machines and named Cashpoint by Lloyds Bank. Cashpoint is still a registered trademark of Lloyds Banking Group in the UK but is often used as a generic trademark to refer to ATMs of all UK banks. All were online and issued a variable amount which was immediately deducted from the account. A small number of 2984s were supplied to a U.S. bank. A couple of well known historical models of ATMs include the Atalla Box,[45] IBM 3614, IBM 3624 and 473x series, Diebold 10xx and TABS 9000 series, NCR 1780 and earlier NCR 770 series.

The first switching system to enable shared automated teller machines between banks went into production operation on 3 February 1979, in Denver, Colorado, in an effort by Colorado National Bank of Denver and Kranzley and Company of Cherry Hill, New Jersey.[52]

In 2012, a new ATM at Royal Bank of Scotland allowed customers to withdraw cash up to £130 without a card by inputting a six-digit code requested through their smartphones.[53]

Location

ATMs can be placed at any location but are most often placed near or inside banks, shopping centers/malls, airports, railway stations, metro stations, grocery stores, petrol/gas stations, restaurants, and other locations. ATMs are also found on cruise ships and on some US Navy ships, where sailors can draw out their pay.[55]

ATMs may be on- and off-premises. On-premises ATMs are typically more advanced, multi-function machines that complement a bank branch's capabilities, and are thus more expensive. Off-premises machines are deployed by financial institutions and independent sales organisations (ISOs) where there is a simple need for cash, so they are generally cheaper single-function devices.

In the US, Canada and some Gulf countries, banks may have drive-thru lanes providing access to ATMs using an automobile.

In recent times, countries like India and some countries in Africa are installing solar-powered ATMs in rural areas.[56]

The world's highest ATM is located at the Khunjerab Pass in Pakistan. Installed at an elevation of 4,693 metres (15,397 ft) by the National Bank of Pakistan, it is designed to work in temperatures as low as -40-degree Celsius.[57]

Financial networks

Most ATMs are connected to interbank networks, enabling people to withdraw and deposit money from machines not belonging to the bank where they have their accounts or in the countries where their accounts are held (enabling cash withdrawals in local currency). Some examples of interbank networks include NYCE, PULSE, PLUS, Cirrus, AFFN, Interac,[58] Interswitch, STAR, LINK, MegaLink, and BancNet.

ATMs rely on the authorization of a financial transaction by the card issuer or other authorizing institution on a communications network. This is often performed through an ISO 8583 messaging system.

Many banks charge ATM usage fees. In some cases, these fees are charged solely to users who are not customers of the bank that operates the ATM; in other cases, they apply to all users.

In order to allow a more diverse range of devices to attach to their networks, some interbank networks have passed rules expanding the definition of an ATM to be a terminal that either has the vault within its footprint or utilises the vault or cash drawer within the merchant establishment, which allows for the use of a scrip cash dispenser.

ATMs typically connect directly to their host or ATM Controller on either ADSL or dial-up modem over a telephone line or directly on a leased line. Leased lines are preferable to plain old telephone service (POTS) lines because they require less time to establish a connection. Less-trafficked machines will usually rely on a dial-up modem on a POTS line rather than using a leased line, since a leased line may be comparatively more expensive to operate compared to a POTS line. That dilemma may be solved as high-speed Internet VPN connections become more ubiquitous. Common lower-level layer communication protocols used by ATMs to communicate back to the bank include SNA over SDLC, TC500 over Async, X.25, and TCP/IP over Ethernet.

In addition to methods employed for transaction security and secrecy, all communications traffic between the ATM and the Transaction Processor may also be encrypted using methods such as SSL.[59] 2021

Global use

%252C_OWID.svg.png.webp)

There are no hard international or government-compiled numbers totaling the complete number of ATMs in use worldwide. Estimates developed by ATMIA place the number of ATMs currently in use at 3 million units, or approximately 1 ATM per 3,000 people in the world.[60][61]

To simplify the analysis of ATM usage around the world, financial institutions generally divide the world into seven regions, based on the penetration rates, usage statistics, and features deployed. Four regions (USA, Canada, Europe, and Japan) have high numbers of ATMs per million people.[62][63] Despite the large number of ATMs, there is additional demand for machines in the Asia/Pacific area as well as in Latin America.[64][65] Macau may have the highest density of ATMs at 254 ATMs per 100,000 adults.[66] ATMs have yet to reach high numbers in the Near East and Africa.[67]

Hardware

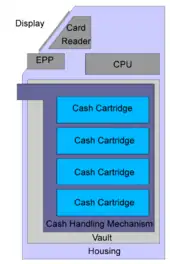

An ATM is typically made up of the following devices:

- CPU (to control the user interface and transaction devices)

- Magnetic or chip card reader (to identify the customer)

- a PIN pad for accepting and encrypting personal identification number EPP4 (similar in layout to a touch tone or calculator keypad), manufactured as part of a secure enclosure

- Secure cryptoprocessor, generally within a secure enclosure

- Display (used by the customer for performing the transaction)

- Function key buttons (usually close to the display) or a touchscreen (used to select the various aspects of the transaction)

- Record printer (to provide the customer with a record of the transaction)

- Vault (to store the parts of the machinery requiring restricted access)

- Housing (for aesthetics and to attach signage to)

- Sensors and indicators

Due to heavier computing demands and the falling price of personal computer–like architectures, ATMs have moved away from custom hardware architectures using microcontrollers or application-specific integrated circuits and have adopted the hardware architecture of a personal computer, such as USB connections for peripherals, Ethernet and IP communications, and use personal computer operating systems.

Business owners often lease ATMs from service providers. However, based on the economies of scale, the price of equipment has dropped to the point where many business owners are simply paying for ATMs using a credit card.

New ADA voice and text-to-speech guidelines imposed in 2010, but required by March 2012[68] have forced many ATM owners to either upgrade non-compliant machines or dispose them if they are not upgradable, and purchase new compliant equipment. This has created an avenue for hackers and thieves to obtain ATM hardware at junkyards from improperly disposed decommissioned machines.[69]

The vault of an ATM is within the footprint of the device itself and is where items of value are kept. Scrip cash dispensers do not incorporate a vault.

Mechanisms found inside the vault may include:

- Dispensing mechanism (to provide cash or other items of value)

- Deposit mechanism including a cheque processing module and bulk note acceptor (to allow the customer to make deposits)

- Security sensors (magnetic, thermal, seismic, gas)

- Locks (to control access to the contents of the vault)

- Journaling systems; many are electronic (a sealed flash memory device based on in-house standards) or a solid-state device (an actual printer) which accrues all records of activity including access timestamps, number of notes dispensed, etc. This is considered sensitive data and is secured in similar fashion to the cash as it is a similar liability.

ATM vaults are supplied by manufacturers in several grades. Factors influencing vault grade selection include cost, weight, regulatory requirements, ATM type, operator risk avoidance practices and internal volume requirements.[70] Industry standard vault configurations include Underwriters Laboratories UL-291 "Business Hours" and Level 1 Safes,[71] RAL TL-30 derivatives,[72] and CEN EN 1143-1 - CEN III and CEN IV.[73][74]

ATM manufacturers recommend that a vault be attached to the floor to prevent theft,[75] though there is a record of a theft conducted by tunnelling into an ATM floor.[76]

Software

With the migration to commodity Personal Computer hardware, standard commercial "off-the-shelf" operating systems and programming environments can be used inside of ATMs. Typical platforms previously used in ATM development include RMX or OS/2.

Today, the vast majority of ATMs worldwide use Microsoft Windows. In early 2014, 95% of ATMs were running Windows XP.[77] A small number of deployments may still be running older versions of the Windows OS, such as Windows NT, Windows CE, or Windows 2000, even though Microsoft still supports only Windows 8.1, Windows 10 and Windows 11.

There is a computer industry security view that general public desktop operating systems(os) have greater risks as operating systems for cash dispensing machines than other types of operating systems like (secure) real-time operating systems (RTOS). RISKS Digest has many articles about ATM operating system vulnerabilities.[78]

Linux is also finding some reception in the ATM marketplace. An example of this is Banrisul, the largest bank in the south of Brazil, which has replaced the MS-DOS operating systems in its ATMs with Linux. Banco do Brasil is also migrating ATMs to Linux. Indian-based Vortex Engineering is manufacturing ATMs that operate only with Linux. Common application layer transaction protocols, such as Diebold 91x (911 or 912) and NCR NDC or NDC+ provide emulation of older generations of hardware on newer platforms with incremental extensions made over time to address new capabilities, although companies like NCR continuously improve these protocols issuing newer versions (e.g. NCR's AANDC v3.x.y, where x.y are subversions). Most major ATM manufacturers provide software packages that implement these protocols. Newer protocols such as IFX have yet to find wide acceptance by transaction processors.[79]

With the move to a more standardised software base, financial institutions have been increasingly interested in the ability to pick and choose the application programs that drive their equipment. WOSA/XFS, now known as CEN XFS (or simply XFS), provides a common API for accessing and manipulating the various devices of an ATM. J/XFS is a Java implementation of the CEN XFS API.

While the perceived benefit of XFS is similar to the Java's "write once, run anywhere" mantra, often different ATM hardware vendors have different interpretations of the XFS standard. The result of these differences in interpretation means that ATM applications typically use a middleware to even out the differences among various platforms.

With the onset of Windows operating systems and XFS on ATMs, the software applications have the ability to become more intelligent. This has created a new breed of ATM applications commonly referred to as programmable applications. These types of applications allows for an entirely new host of applications in which the ATM terminal can do more than only communicate with the ATM switch. It is now empowered to connected to other content servers and video banking systems.

Notable ATM software that operates on XFS platforms include Triton PRISM, Diebold Agilis EmPower, NCR APTRA Edge, Absolute Systems AbsoluteINTERACT, KAL Kalignite Software Platform, Phoenix Interactive VISTAatm, Wincor Nixdorf ProTopas, Euronet EFTS and Intertech inter-ATM.

With the move of ATMs to industry-standard computing environments, concern has risen about the integrity of the ATM's software stack.[80]

Impact on labor

The number of human bank tellers in the United States increased from approximately 300,000 in 1970 to approximately 600,000 in 2010. Counter-intuitively, a contributing factor may be the introduction of automated teller machines. ATMs let a branch operate with fewer tellers, making it cheaper for banks to open more branches. This likely resulted in more tellers being hired to handle non-automated tasks, but further automation and online banking may reverse this increase.[81]

Security

Security, as it relates to ATMs, has several dimensions. ATMs also provide a practical demonstration of a number of security systems and concepts operating together and how various security concerns are addressed.

Physical

Early ATM security focused on making the terminals invulnerable to physical attack; they were effectively safes with dispenser mechanisms. A number of attacks resulted, with thieves attempting to steal entire machines by ram-raiding.[82] Since the late 1990s, criminal groups operating in Japan improved ram-raiding by stealing and using a truck loaded with heavy construction machinery to effectively demolish or uproot an entire ATM and any housing to steal its cash.

Another attack method, plofkraak, is to seal all openings of the ATM with silicone and fill the vault with a combustible gas or to place an explosive inside, attached, or near the machine. This gas or explosive is ignited and the vault is opened or distorted by the force of the resulting explosion and the criminals can break in.[83] This type of theft has occurred in the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Denmark, Germany, Australia,[84][85] and the United Kingdom.[86] These types of attacks can be prevented by a number of gas explosion prevention devices also known as gas suppression system. These systems use explosive gas detection sensor to detect explosive gas and to neutralise it by releasing a special explosion suppression chemical which changes the composition of the explosive gas and renders it ineffective.

Several attacks in the UK (at least one of which was successful) have involved digging a concealed tunnel under the ATM and cutting through the reinforced base to remove the money.[76]

Modern ATM physical security, per other modern money-handling security, concentrates on denying the use of the money inside the machine to a thief, by using different types of Intelligent Banknote Neutralisation Systems.

A common method is to simply rob the staff filling the machine with money. To avoid this, the schedule for filling them is kept secret, varying and random. The money is often kept in cassettes, which will dye the money if incorrectly opened.

Transactional secrecy and integrity

The security of ATM transactions relies mostly on the integrity of the secure cryptoprocessor: the ATM often uses general commodity components that sometimes are not considered to be "trusted systems".

Encryption of personal information, required by law in many jurisdictions, is used to prevent fraud. Sensitive data in ATM transactions are usually encrypted with DES, but transaction processors now usually require the use of Triple DES.[87] Remote Key Loading techniques may be used to ensure the secrecy of the initialisation of the encryption keys in the ATM. Message Authentication Code (MAC) or Partial MAC may also be used to ensure messages have not been tampered with while in transit between the ATM and the financial network.

Customer identity integrity

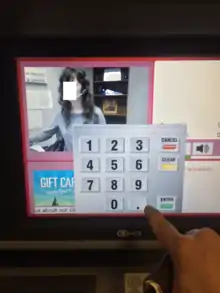

There have also been a number of incidents of fraud by Man-in-the-middle attacks, where criminals have attached fake keypads or card readers to existing machines. These have then been used to record customers' PINs and bank card information in order to gain unauthorised access to their accounts. Various ATM manufacturers have put in place countermeasures to protect the equipment they manufacture from these threats.[88][89]

Alternative methods to verify cardholder identities have been tested and deployed in some countries, such as finger and palm vein patterns,[90] iris, and facial recognition technologies. Cheaper mass-produced equipment has been developed and is being installed in machines globally that detect the presence of foreign objects on the front of ATMs, current tests have shown 99% detection success for all types of skimming devices.[91]

Device operation integrity

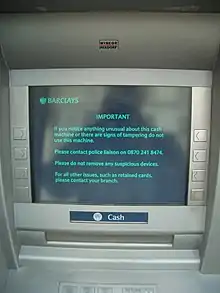

Openings on the customer side of ATMs are often covered by mechanical shutters to prevent tampering with the mechanisms when they are not in use. Alarm sensors are placed inside ATMs and their servicing areas to alert their operators when doors have been opened by unauthorised personnel.

To protect against hackers, ATMs have a built-in firewall. Once the firewall has detected malicious attempts to break into the machine remotely, the firewall locks down the machine.

Rules are usually set by the government or ATM operating body that dictate what happens when integrity systems fail. Depending on the jurisdiction, a bank may or may not be liable when an attempt is made to dispense a customer's money from an ATM and the money either gets outside of the ATM's vault, or was exposed in a non-secure fashion, or they are unable to determine the state of the money after a failed transaction.[92] Customers often commented that it is difficult to recover money lost in this way, but this is often complicated by the policies regarding suspicious activities typical of the criminal element.[93]

Customer security

In some countries, multiple security cameras and security guards are a common feature.[94] In the United States, The New York State Comptroller's Office has advised the New York State Department of Banking to have more thorough safety inspections of ATMs in high crime areas.[95]

Consultants of ATM operators assert that the issue of customer security should have more focus by the banking industry;[96] it has been suggested that efforts are now more concentrated on the preventive measure of deterrent legislation than on the problem of ongoing forced withdrawals.[97]

At least as far back as 30 July 1986, consultants of the industry have advised for the adoption of an emergency PIN system for ATMs, where the user is able to send a silent alarm in response to a threat.[98] Legislative efforts to require an emergency PIN system have appeared in Illinois,[99] Kansas[100][101] and Georgia,[102] but none has succeeded yet. In January 2009, Senate Bill 1355 was proposed in the Illinois Senate that revisits the issue of the reverse emergency PIN system.[103] The bill is again supported by the police and opposed by the banking lobby.[104]

In 1998, three towns outside Cleveland, Ohio, in response to an ATM crime wave, adopted legislation requiring that an emergency telephone number switch be installed at all outdoor ATMs within their jurisdiction. In the wake of a homicide in Sharon Hill, Pennsylvania, the city council passed an ATM security bill as well.

In China and elsewhere, many efforts to promote security have been made. On-premises ATMs are often located inside the bank's lobby, which may be accessible 24 hours a day. These lobbies have extensive security camera coverage, a courtesy telephone for consulting with the bank staff, and a security guard on the premises. Bank lobbies that are not guarded 24 hours a day may also have secure doors that can only be opened from outside by swiping the bank card against a wall-mounted scanner, allowing the bank to identify which card enters the building. Most ATMs will also display on-screen safety warnings and may also be fitted with convex mirrors above the display allowing the user to see what is happening behind them.

As of 2013, the only claim available about the extent of ATM-connected homicides is that they range from 500 to 1,000 per year in the US, covering only cases where the victim had an ATM card and the card was used by the killer after the known time of death.[105]

Jackpotting

The term jackpotting is used to describe one method criminals utilize to steal money from an ATM. The thieves gain physical access through a small hole drilled in the machine. They disconnect the existing hard drive and connect an external drive using an industrial endoscope. They then depress an internal button that reboots the device so that it is now under the control of the external drive. They can then have the ATM dispense all of its cash.[106]

Encryption

In recent years, many ATMs also encrypt the hard disk. This means that actually creating the software for jackpotting is more difficult, and provides more security for the ATM.

Uses

ATMs were originally developed as cash dispensers, and have evolved to provide many other bank-related functions:

- Paying routine bills, fees, and taxes (utilities, phone bills, social security, legal fees, income taxes, etc.)

- Printing or ordering bank statements

- Updating passbooks

- Cash advances

- Cheque Processing Module

- Paying (in full or partially) the credit balance on a card linked to a specific current account.

- Transferring money between linked accounts (such as transferring between accounts)

- Deposit currency recognition, acceptance, and recycling[107][108]

In some countries, especially those which benefit from a fully integrated cross-bank network (e.g.: Multibanco in Portugal), ATMs include many functions that are not directly related to the management of one's own bank account, such as:

- Loading monetary value into stored-value cards

- Adding pre-paid cell phone / mobile phone credit.

- Purchasing

- Concert tickets

- Gold[109]

- Lottery tickets

- Movie tickets

- Postage stamps.

- Train tickets

- Shopping mall gift certificates.

- Donating to charities[110]

Increasingly, banks are seeking to use the ATM as a sales device to deliver pre approved loans and targeted advertising using products such as ITM (the Intelligent Teller Machine) from Aptra Relate from NCR.[111] ATMs can also act as an advertising channel for other companies.[112]*

However, several different ATM technologies have not yet reached worldwide acceptance, such as:

- Videoconferencing with human tellers, known as video tellers[113]

- Biometrics, where authorization of transactions is based on the scanning of a customer's fingerprint, iris, face, etc.[114][115][116]

- Cheque/cash Acceptance, where the machine accepts and recognises cheques and/or currency without using envelopes[117] Expected to grow in importance in the US through Check 21 legislation.

- Bar code scanning[118]

- On-demand printing of "items of value" (such as movie tickets, traveler's cheques, etc.)

- Dispensing additional media (such as phone cards)

- Co-ordination of ATMs with mobile phones[119]

- Integration with non-banking equipment[120][121]

- Games and promotional features[122]

- CRM through the ATM

Videoconferencing teller machines are currently referred to as Interactive Teller Machines. Benton Smith, in the Idaho Business Review writes "The software that allows interactive teller machines to function was created by a Salt Lake City-based company called uGenius, a producer of video banking software. NCR, a leading manufacturer of ATMs, acquired uGenius in 2013 and married its own ATM hardware with uGenius' video software."[123]

- Pharmacy dispensing units[124]

Reliability

Before an ATM is placed in a public place, it typically has undergone extensive testing with both test money and the backend computer systems that allow it to perform transactions. Banking customers also have come to expect high reliability in their ATMs,[125] which provides incentives to ATM providers to minimise machine and network failures. Financial consequences of incorrect machine operation also provide high degrees of incentive to minimise malfunctions.[126]

ATMs and the supporting electronic financial networks are generally very reliable, with industry benchmarks typically producing 98.25% customer availability for ATMs[127] and up to 99.999% availability for host systems that manage the networks of ATMs. If ATM networks do go out of service, customers could be left without the ability to make transactions until the beginning of their bank's next time of opening hours.

This said, not all errors are to the detriment of customers; there have been cases of machines giving out money without debiting the account, or giving out higher value notes as a result of incorrect denomination of banknote being loaded in the money cassettes.[128] The result of receiving too much money may be influenced by the card holder agreement in place between the customer and the bank.[129][130]

Errors that can occur may be mechanical (such as card transport mechanisms; keypads; hard disk failures; envelope deposit mechanisms); software (such as operating system; device driver; application); communications; or purely down to operator error.

To aid in reliability, some ATMs print each transaction to a roll-paper journal that is stored inside the ATM, which allows its users and the related financial institutions to settle things based on the records in the journal in case there is a dispute. In some cases, transactions are posted to an electronic journal to remove the cost of supplying journal paper to the ATM and for more convenient searching of data.

Improper money checking can cause the possibility of a customer receiving counterfeit banknotes from an ATM. While bank personnel are generally trained better at spotting and removing counterfeit cash,[131][132] the resulting ATM money supplies used by banks provide no guarantee for proper banknotes, as the Federal Criminal Police Office of Germany has confirmed that there are regularly incidents of false banknotes having been dispensed through ATMs.[133] Some ATMs may be stocked and wholly owned by outside companies, which can further complicate this problem. Bill validation technology can be used by ATM providers to help ensure the authenticity of the cash before it is stocked in the machine; those with cash recycling capabilities include this capability.[134]

In India, whenever a transaction fails with an ATM due to network or technical issues and if the amount does not get dispensed in spite of the account being debited then the banks are supposed to return the debited amount to the customer within seven working days from the day of receipt of a complaint. Banks are also liable to pay the late fees in case of delay in repayment of funds post seven days.[135]

Fraud

As with any device containing objects of value, ATMs and the systems they depend on to function are the targets of fraud. Fraud against ATMs and people's attempts to use them takes several forms.

The first known instance of a fake ATM was installed at a shopping mall in Manchester, Connecticut, in 1993. By modifying the inner workings of a Fujitsu model 7020 ATM, a criminal gang known as the Bucklands Boys stole information from cards inserted into the machine by customers.[136]

WAVY-TV reported an incident in Virginia Beach in September 2006 where a hacker, who had probably obtained a factory-default administrator password for a filling station's white-label ATM, caused the unit to assume it was loaded with US$5 bills instead of $20s, enabling himself—and many subsequent customers—to walk away with four times the money withdrawn from their accounts.[137] This type of scam was featured on the TV series The Real Hustle.

ATM behaviour can change during what is called "stand-in" time, where the bank's cash dispensing network is unable to access databases that contain account information (possibly for database maintenance). In order to give customers access to cash, customers may be allowed to withdraw cash up to a certain amount that may be less than their usual daily withdrawal limit, but may still exceed the amount of available money in their accounts, which could result in fraud if the customers intentionally withdraw more money than they had in their accounts.[138]

Card fraud

In an attempt to prevent criminals from shoulder surfing the customer's personal identification number (PIN), some banks draw privacy areas on the floor.

For a low-tech form of fraud, the easiest is to simply steal a customer's card along with its PIN. A later variant of this approach is to trap the card inside of the ATM's card reader with a device often referred to as a Lebanese loop. When the customer gets frustrated by not getting the card back and walks away from the machine, the criminal is able to remove the card and withdraw cash from the customer's account, using the card and its PIN.

This type of fraud has spread globally. Although somewhat replaced in terms of volume by skimming incidents, a re-emergence of card trapping has been noticed in regions such as Europe, where EMV chip and PIN cards have increased in circulation.[139]

Another simple form of fraud involves attempting to get the customer's bank to issue a new card and its PIN and stealing them from their mail.[140]

By contrast, a newer high-tech method of operating, sometimes called card skimming or card cloning, involves the installation of a magnetic card reader over the real ATM's card slot and the use of a wireless surveillance camera or a modified digital camera or a false PIN keypad to observe the user's PIN. Card data is then cloned into a duplicate card and the criminal attempts a standard cash withdrawal. The availability of low-cost commodity wireless cameras, keypads, card readers, and card writers has made it a relatively simple form of fraud, with comparatively low risk to the fraudsters.[141]

In an attempt to stop these practices, countermeasures against card cloning have been developed by the banking industry, in particular by the use of smart cards which cannot easily be copied or spoofed by unauthenticated devices, and by attempting to make the outside of their ATMs tamper evident. Older chip-card security systems include the French Carte Bleue, Visa Cash, Mondex, Blue from American Express[142] and EMV '96 or EMV 3.11. The most actively developed form of smart card security in the industry today is known as EMV 2000 or EMV 4.x.

EMV is widely used in the UK (Chip and PIN) and other parts of Europe, but when it is not available in a specific area, ATMs must fall back to using the easy–to–copy magnetic stripe to perform transactions. This fallback behaviour can be exploited.[143] However, the fallback option has been removed on the ATMs of some UK banks, meaning if the chip is not read, the transaction will be declined.

Card cloning and skimming can be detected by the implementation of magnetic card reader heads and firmware that can read a signature embedded in all magnetic stripes during the card production process. This signature, known as a "MagnePrint" or "BluPrint", can be used in conjunction with common two-factor authentication schemes used in ATM, debit/retail point-of-sale and prepaid card applications.

The concept and various methods of copying the contents of an ATM card's magnetic stripe onto a duplicate card to access other people's financial information were well known in the hacking communities by late 1990.[144]

In 1996, Andrew Stone, a computer security consultant from Hampshire in the UK, was convicted of stealing more than £1 million by pointing high-definition video cameras at ATMs from a considerable distance and recording the card numbers, expiry dates, etc. from the embossed detail on the ATM cards along with video footage of the PINs being entered. After getting all the information from the videotapes, he was able to produce clone cards which not only allowed him to withdraw the full daily limit for each account, but also allowed him to sidestep withdrawal limits by using multiple copied cards. In court, it was shown that he could withdraw as much as £10,000 per hour by using this method. Stone was sentenced to five years and six months in prison.[145]

Related devices

A talking ATM is a type of ATM that provides audible instructions so that people who cannot read a screen can independently use the machine, therefore effectively eliminating the need for assistance from an external, potentially malevolent source. All audible information is delivered privately through a standard headphone jack on the face of the machine. Alternatively, some banks such as the Nordea and Swedbank use a built-in external speaker which may be invoked by pressing the talk button on the keypad.[146] Information is delivered to the customer either through pre-recorded sound files or via text-to-speech speech synthesis.

A postal interactive kiosk may share many components of an ATM (including a vault), but it only dispenses items related to postage.[147][148]

A scrip cash dispenser may have many components in common with an ATM, but it lacks the ability to dispense physical cash and consequently requires no vault. Instead, the customer requests a withdrawal transaction from the machine, which prints a receipt or scrip. The customer then takes this receipt to a nearby sales clerk, who then exchanges it for cash from the till.[149]

A teller assist unit (TAU) is distinct in that it is designed to be operated solely by trained personnel and not by the general public, does integrate directly into interbank networks, and usually is controlled by a computer that is not directly integrated into the overall construction of the unit.

A Web ATM is an online interface for ATM card banking that uses a smart card reader. All the usual ATM functions are available, except for withdrawing cash. Most banks in Taiwan provide these online services.[150][151]

See also

- ATM Industry Association (ATMIA)

- Automated cash handling

- Banknote counter

- Bitcoin ATM

- Cash register

- EFTPOS

- Electronic funds transfer

- Financial cryptography

- Key management

- Payroll

- Phantom withdrawal

- RAS syndrome

- Self service

- Teller system

- Verification and validation

References

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 12 August 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- "training.gov.au - FNSRTS307A - Maintain Automatic Teller Machine (ATM) services". Archived from the original on 7 April 2014.

- Cambridge Dictionary Automatic Teller Machine Archived 7 April 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- "Interac FAQ". Interac Association. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "Automatic Bank Machine definition from a Canadian bank, Scotiabank".

- Canada, Financial Consumer Agency of (8 June 2018). "ATM fees - Canada.ca". www.canada.ca. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "ATM and Banking Centre Network | CIBC". www.cibc.com. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- "TD Green Machine ATM Machines | TD Canada Trust". www.tdcanadatrust.com. Retrieved 29 July 2018.

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- Schlichter, Sarah (5 February 2007). "Using ATM's abroad - Travel - Travel Tips - NBC News". NBC News. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "ATM Industry Association". Archived from the original on 16 October 2015.

- "3 Million ATMs Worldwide By 2015: ATM Association". Archived from the original on 26 June 2015.

- Shopping centres prepare to go cashless as ATMs disappear Archived 4 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- "A Brief History of the ATM". The Atlantic. 26 March 2015. Archived from the original on 28 April 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Batiz-Lazo, Bernardo (27 March 2013). "How the ATM Revolutionized the Banking Business". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014.

- "ATMIA 50th Anniversary Factsheet" (PDF). www.atmia.com. ATM Industry Association. October 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- "Machine Accepts Bank Deposits", The New York Times, 12 April 1961

- US patent 3079603, Luther G Simjian, "Depository machine combined with image recording means", issued 1963-02-26

- "Universal Match Maps Acquisition", The New York Times, 22 March 1961

- "From punchcard to prestaging: 50 years of ATM innovation". ATM Marketplace. 31 July 2013. Archived from the original on 15 August 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- GB patent 959713, Adrian Walter Francis Ashfield, "Access Controller", published 1962-02-15, issued 1964-06-03, assigned to Kins Developments Ltd

- 'Fast Machine With a Buck',"Pacific Star and Stripes", 7 July 1966

- 'Instant Cash with a Credit Card', "ABA Banking Journal", January 1967

- Batiz-Lazo, Bernardo; Reid, Robert J. K. (30 June 2008). "Evidence from the Patent Record on the Development of Cash Dispensing Technology" (PDF). Munich Personal RePEc Archive. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- "Enfield's cash gift to the world". BBC London. 27 June 2007. Archived from the original on 3 November 2015.

- Milligan, Brian (25 June 2007). "The man who invented the cash machine". BBC News. Archived from the original on 26 December 2009. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "ATM inventor honoured". BBC News. 31 December 2004. Archived from the original on 8 June 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- Harper, Tom; Batiz-Lazo, Bernardo (2013). Cash Box: The Invention and Globalization of the ATM. Networld Media Group. ISBN 978-1935497622.

- "ATM inventor John Shepherd-Barron dies at age of 84 on 20th May 2010". Los Angeles Times. 19 May 2010. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010.

- Mary Bellis. "The ATM of John Shepherd Barron". About.com. Retrieved 2011-04-29.

- B. Batiz-Lazo (June 2007). "The emergence and evolution of ATM networks in the UK, c. 1967–2000". Business History, 2009 (51:1). Taylor and Francis, 2009. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - B. Batiz-Lazo, T. Karlsson and B. Thodenius (24 April 2014). "The origins of the cashless society: cash dispensers, direct to account payments and the development of on-line real-time networks, c. 1965–1985". Essays in Economic & Business History. Essays in Economic and Business History, 2014 (32). The Economic and Business History Society, 2014. 32: 100–137. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- "Automated Teller Terminal AT-20P". IPSJ Computer Museum. Information Processing Society of Japan. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- "James Goodfellow, Series 2, Pioneers - BBC Radio 4 Extra". BBC. Retrieved 29 March 2018.

- B. Batiz-Lazo and R. J. K. Reid (30 June 2008). "Evidence from the patent record on the development of cash dispensing technology". History of Telecommunications Conference, 2008. Histelcon 2008. IEEE. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Marino Gomez-Santos (9 January 1969). "Bancomat (In Spanish)". ABC. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- "Bancomat Banesto (commercial ad with instructions for use in Spanish)". ABC. 18 March 1969. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- Essinger, James (1987). ATM Networks: Their Organization, Security and Future. Elsevier International.

- Kirkpatrick, Rob (2009). 1969: The Year Everything Changed. Skyhorse Publishing Inc. p. 266. ISBN 9781602393660. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011.

- Popular Mechanics - Google Books. Hearst Magazines. December 2005. Archived from the original on 25 December 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Interview with Mr. Don Wetzel". Americanhistory.si.edu. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Automatic teller machine". The History of Computing Project. Thocp.net. 17 April 2006. Archived from the original on 20 February 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Aspray, W. (1997). "The Intel 4004 microprocessor: what constituted invention?". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. 19 (3): 4–15. doi:10.1109/85.601727. ISSN 1058-6180. S2CID 15782735.

- Stiennon, Richard (17 June 2014). "Key Management a Fast Growing Space". SecurityCurrent. IT-Harvest. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Bátiz-Lazo, Bernardo (2018). Cash and Dash: How ATMs and Computers Changed Banking. Oxford University Press. pp. 284 & 311. ISBN 9780191085574.

- "The Economic Impacts of NIST's Data Encryption Standard (DES) Program" (PDF). National Institute of Standards and Technology. United States Department of Commerce. October 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 August 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Langford, Susan (2013). "ATM Cash-out Attacks" (PDF). Hewlett Packard Enterprise. Hewlett-Packard. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "ID System Designed as NCR 270 Upgrade". Computerworld. IDG Enterprise. 12 (7): 49. 13 February 1978.

- "Four Products for On-Line Transactions Unveiled". Computerworld. IDG Enterprise. 10 (4): 3. 26 January 1976.

- Bátiz-Lazo, Bernardo (2018). Cash and Dash: How ATMs and Computers Changed Banking. Oxford University Press. p. 311. ISBN 9780191085574.

- Konheim, Alan G. (1 April 2016). "Automated teller machines: their history and authentication protocols". Journal of Cryptographic Engineering. 6 (1): 1–29. doi:10.1007/s13389-015-0104-3. ISSN 2190-8516. S2CID 1706990. Archived from the original on 22 July 2019. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- personal knowledge of William Patterson who was there supporting the network

- "ATMs to operate without a card". BBC News. 12 June 2012. Archived from the original on 13 June 2012.

- "The World's Highest ATM". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Overview: Navy Cash/Marine Cash: Programs and Systems: Financial Management Service Archived 3 March 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Fms.treas.gov. Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- NT, Balanarayan (14 March 2010). "The nano of ATMs for rural masses comes to town". Daily News and Analysis. Bangalore. Archived from the original on 25 May 2015. Retrieved 24 May 2015.

- "NBP installs 'World's Highest ATM' in Pakistan". Daily Pakistan. 5 September 2016. Archived from the original on 27 April 2017. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

- "Interac Cash web page". Retrieved 2 July 2018.

- Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "ATM Industry Association Global ATM Clock". Atmia.com. Archived from the original on 13 September 2011. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- "A million new ATMs installed in the last five years" (PDF). rbrlondon.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- "Interac Association - Media > Statistics > ABM Stats". Archived from the original on 5 October 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2006.

- "Statistics on payment and settlement systems in selected countries - Figures for 2004". Bis.org. 31 March 2006. Archived from the original on 17 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Central bank payment system information". Bis.org. 5 February 2001. Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "EIU.com". EIU.com. Archived from the original on 11 November 2013. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- Fraiser, Naill (5 May 2017). "ATM withdrawals in Macau top HK$10 billion a month, as authorities ensure machines never run dry, source says". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 5 May 2017.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 August 2006. Retrieved 11 August 2006.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Summary of New 2010 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) ATM Standards" (PDF). firstdata.com. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 June 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "How to Properly Dispose of Decommissioned ATM". ATMDepot.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "ATM ATM Frequently Asked Questions". Atmdepot.com. Archived from the original on 19 October 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Scope for UL 291". Ulstandardsinfonet.ul.com. 21 December 2004. Archived from the original on 5 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Archived 22 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Home".

- "BSI: Standards, Training, Testing, Assessment & Certification". Bsonline.bsi-global.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Triton Systems | ATM manufacturer" (PDF). Tritonatm.com. 17 November 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Thieves dig 100ft tunnel to steal cash in Levenshulme". BBC. 14 January 2012. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- "The death of Windows XP will impact 95 percent of the world's ATMs". The Verge. Archived from the original on 4 December 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- "Risks search results for "cash machine"". Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- "Messaging standard to give multiple channels a common language". selfserviceworld.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Technology News: Security: Windows Cash-Machine Worm Generates Concern". Technewsworld.com. Archived from the original on 18 March 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Tess Townsend (8 May 2017). "Eric Schmidt said ATMs led to more jobs for bank tellers. It's not that simple". Recode.

- "Things to Keep in Mind when Opting for Free ATM Placements". Archived from the original on 21 November 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- "ATM bombings up 3000%". News24. 12 July 2008. Archived from the original on 14 January 2012. Retrieved 7 April 2011.

- "Dutch blaggers explode ATMs". The Register. Archived from the original on 10 August 2017.

- "Attacks on banks devised in Europe - National". The Sydney Morning Herald. 25 November 2008. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Summers, Nick (27 January 2015). "Boom: Inside a British Bank Bombing Spree". Businessweek. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- Archived 12 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "The No. 1 ATM security concern". ATM Marketplace. Archived from the original on 18 July 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Diebold ATM Fraud" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 September 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Archived 3 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 1 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Kilpailu- ja kuluttajavirasto".

- "Banking". Moneycentral.msn.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "NYSBD - Text of the ATM Safety Act". Banking.state.ny.us. 1 June 1997. Archived from the original on 10 April 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "DiNapoli Calls for Better Oversight of Bank ATMs". Osc.state.ny.us. 4 October 2007. Archived from the original on 10 June 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Archived 9 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Archived 9 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- Representative Mario Biaggi, Congressional Record, 30 July 1986, Page 18232 et seq.

- "ATM Report". Obre.state.il.us. Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Credit Union tech-talk news and technology resource Archived 16 October 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Cunews.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- "Senate Bill No. 333" (PDF). www.kansas.gov. 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 December 2018. Retrieved 14 December 2018.

- "sb379_SB_379_PF_2.html". Legis.state.ga.us. Archived from the original on 31 August 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Illinois General Assembly - Bill Status for SB1355". Ilga.gov. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Kravetz, Andy (18 February 2009). "ATM software aimed at reversing crime - Peoria, IL". pjstar.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Could Reverse PIN Save Lives at ATM? Archived 13 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Wctv.tv. Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- "ATM makers warn of 'jackpotting' hacks on U.S. machines". Reuters. 27 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- "Rising interest rates, gas prices hit vault-cash providers". selfserviceworld.com. Archived from the original on 29 March 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "NCR and Fujitsu Develop Cash Deposit and Bill Recycling Module for ATMs : Fujitsu Global". Fujitsu.com. Archived from the original on 3 April 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Lynn, Matthew, "What will replace the dollar as global currency?: Gold? Renminbi? Maybe commodities?" Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, MarketWatch, 7 July 2011 12:00 a.m. EDT. Retrieved 2011-07-07.

- Harvey, Rachel (10 January 2006). "Asia-Pacific | Indonesians make ATM sacrifices". BBC News. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Wincor Nixdorf Germany" (in German). Wincor-nixdorf.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "ATM:ad First For Comic Relief". creativematch. 10 March 2005. Archived from the original on 29 September 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Fernandes, Deirdre (5 September 2013). "Boston customers test new video ATMs". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 13 October 2013.

- "Japan Post to go with fingerprints for ATMs | The Japan Times Online". Search.japantimes.co.jp. 6 August 2006. Archived from the original on 15 August 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- ""Place Your Hand on the Scanner" | Science and Technology | Trends in Japan". Web Japan. 10 May 2005. Archived from the original on 3 September 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Mastrull, Diane (11 November 1996). "Sensar has its eye on the prize with $42 million Japanese deal | Philadelphia Business Journal". Bizjournals.com. Archived from the original on 17 April 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "BAI Banking Strategies Magazine - Articles Online". Bai.org. 1 February 2011. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "The Check is NOT in the Mail". Accurapid.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Japanese bank to allow cellphone ATM access". Engadget. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Industrial Automated Gas Pumping Station and ATM MCF547x ColdFire Solutions By Freescale". Freescale.com. Archived from the original on 16 March 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "NRT Technology Corporation - Gaming and casino solutions: QuickJack". Nrtpos.com. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Business | Bank puts the 'fun' into 'funds'". BBC News. 20 July 2005. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Smith, Benton Alexander (16 June 2016). "Interactive teller machines allow tellers to work remotely". The Idaho Business Review.

- "These ATMs have swopped bills for pills. Here's why". Bhekisisa. 7 November 2018. Retrieved 15 February 2019.

- "Barking Up the Wrong Tree – Factors Influencing Customer Satisfaction in Retail Banking in the UK - Page 5". Managementjournals.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Rebecca Allison (16 January 2003). "ATM gives out free cash and lands family in court | UK news". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Archived 22 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- "Double money in cash point error". BBC News. 28 April 2004. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009.

- "RBC Royal Bank Card Products - Consumer Visa Cards - Cardholder Agreement". Archived from the original on 28 June 2006. Retrieved 5 August 2006.

- "Europe | Mad rush to faulty ATM in France". BBC News. 23 December 2005. Archived from the original on 15 January 2009. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Archived 10 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- "Materials- Bank Notes- Bank of Canada". Bankofcanada.ca. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Falschgeld: Blüten aus dem Geldautomat? - Wirtschaft". Stern.De. 5 May 2004. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Wincor Nixdorf Germany" (in German). Wincor-nixdorf.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Reserve Bank of India - Function Wise Monetary".

- Patton, Phil (May 1993). "1.05: The Bucklands Boys and Other Tales of the ATM". Wired. Archived from the original on 29 October 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Video". Cnn.com. 6 June 2005. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Kennison v Daire [1986] HCA 4; (1986) 160 CLR 129 (20 February 1986)". Austlii.edu.au. 20 February 1986. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "ATM Security Issues & ATM Fraud Issues by Geography | ATMSecurity.com ATM Security news ATM Security issues ATM fraud info ATM". Atmsecurity.com. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 24 October 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 24 July 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2008.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - snopes (29 March 2016). "Skimming with ATM Cameras : snopes.com". snopes.

- "What the Hell Do Smart Cards Do?". Fast Company. 28 February 2002. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Tamil Nadu / Chennai News : Four more held in fake credit card racket case". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 19 May 2006. Archived from the original on 10 August 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Fredric L. Rice, Organised Crime Civilian Response. "Phrack Classic Volume Three, Issue 32, File #1 of XX Phrack Classic Newsletter Issue XXXII". Skepticfiles.org. Archived from the original on 21 November 2010. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Stephen Castell. "Seeking after the truth in computer evidence: any proof of ATM fraud? — ITNOW". Itnow.oxfordjournals.org. doi:10.1093/combul/38.6.17. Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- pepsi says (25 January 2011). "Why is there braille on drive-up ATMs?". Zidbits. Archived from the original on 29 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Postal Service Mailing Kiosks Now in Every State". Usps.com. 30 December 2004. Archived from the original on 3 January 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- Automated Postal Centers Archived 13 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Lunewsviews.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-02.

- "About Script ATMs: How Do Cashless ATMs Work? - What is Scrip, or Cashless ATMs?". Atmscrip.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2011.

- "Megabank WebATM". Archived from the original on 19 March 2015.

- "Post Office Bank WebATM". Archived from the original on 9 April 2015.

Further reading

- Ali, Peter Ifeanyichukwu. "Impact of automated teller machine on banking services delivery in Nigeria: a stakeholder analysis." Brazilian Journal of Education, Technology and Society 9.1 (2016): 64–72. online

- Bátiz-Lazo, Bernardo. Cash and Dash: How ATMs and Computers Changed Banking (Oxford University Press, 2018). online review

- Batiz-Lazo, Bernardo. "Emergence and evolution of ATM networks in the UK, 1967–2000." Business History 51.1 (2009): 1-27. online

- Batiz-Lazo, Bernardo, and Gustavo del Angel. The Dawn of the Plastic Jungle: The Introduction of the Credit Card in Europe and North America, 1950-1975 (Hoover Institution, 2016), abstract

- Bessen, J. Learning by Doing: The Real Connection between Innovation, Wages, and Wealth (Yale UP, 2015)

- Hota, Jyotiranjan, Saboohi Nasim, and Sasmita Mishra. "Drivers and Barriers to Adoption of Multivendor ATM Technology in India: Synthesis of Three Empirical Studies." Journal of Technology Management for Growing Economies 9.1 (2018): 89-102. online

- McDysan, David E., and Darren L. Spohn. ATM theory and applications (McGraw-Hill Professional, 1998).

- Mkpojiogu, Emmanuel OC, and A. Asuquo. "The user experience of ATM users in Nigeria: a systematic review of empirical papers." Journal of Research in National Development (2018). online Archived 18 May 2020 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- The Money Machines: An account of US cash machine history; By Ellen Florian, Fortune.com

- Automated teller machine at Curlie

- World Map and Chart of Automated Teller Machines per 100,000 Adults by Lebanese-economy-forum, World Bank data