Sea of Azov

The Sea of Azov (Russian: Азовское море, romanized: Azovskoye more; Ukrainian: Азовське море, romanized: Azovs’ke more)[3] is a sea in Eastern Europe connected to the Black Sea by the narrow (about 4 km or 2.5 mi) Strait of Kerch, and is sometimes regarded as a northern extension of the Black Sea.[4][5] The sea is bounded by Russia on the east, by Ukraine on the northwest, and by Crimea on the southwest.

| Sea of Azov | |

|---|---|

Sea of Azov shoreline at Yalta, Donetsk Oblast | |

Sea of Azov | |

Sea of Azov, upper right | |

| Coordinates | 46°N 37°E |

| Type | Sea |

| Primary inflows | Don and Kuban |

| Basin countries | Russia, Ukraine |

| Max. length | 360 km (220 mi)[1] |

| Max. width | 180 km (110 mi)[1] |

| Surface area | 39,000 km2 (15,000 sq mi)[1][2] |

| Average depth | 7 metres (23 ft)[1] |

| Max. depth | 14 m (46 ft)[1] |

| Water volume | 290 km3 (240×106 acre⋅ft)[1] |

The sea is largely affected by the inflow of the Don, Kuban, and other rivers, which bring sand, silt, and shells, which in turn form numerous bays, limans, and narrow spits. Because of these deposits, the sea bottom is relatively smooth and flat with the depth gradually increasing toward the middle. Also, due to the river inflow, water in the sea has low salinity and a high amount of biomass (such as green algae) that affects the water colour. Abundant plankton result in unusually high fish productivity. The sea shores and spits are low; they are rich in vegetation and bird colonies. The Sea of Azov is the shallowest sea in the world, with the depth varying between 0.9 and 14 metres (3 and 46 ft).[1][6][7][8][9] There is a constant outflow of water from the Sea of Azov to the Black Sea.

Names

The name is likely to derive from the settlement of an area around Azov, whose name comes from the Kipchak Turkish asak or azaq 'lowlands'.[10] A Russian pseudo-etymology, however, instead derives it from an eponymous Cuman prince named "Azum" or "Asuf", said to have been killed defending his town in 1067.[11] A formerly common spelling of the name in English was the Sea of Azoff.[12]

In antiquity, the sea had other names (Latin: Palus Maeotis; [13] Greek: Μαιῶτις λίμνη[14] or now Latin: mare Asoviense;[15]). In antiquity, the sea was usually known as the Maeotis Swamp (Ancient Greek: ἡ Μαιῶτις λίμνη, hē Maiōtis límnē; Latin: Palus Maeotis) from the marshlands to its northeast.[16] It remains unclear whether it was named for the nearby Maeotians or if that name was applied broadly to various peoples who happened to live beside it.[16] Other names included Lake Maeotis or Maeotius (Mæotius or Mæotis Lacus);[17] the Maeotian or Maeotic Sea (Mæotium or Mæoticum Æquor);[18][19] the Cimmerian or Scythican Swamps (Cimmeriae[20] or Scythicæ Paludes);[21] and the Cimmerian or Bosporic Sea (Cimmericum or Bosporicum Mare).[22] The Maeotians themselves were said by Pliny to call the sea Temarunda (alternative spellings Temarenda and Temerinda), meaning "Mother of Waters".[23]

The medieval Russians knew it as the Sea of Surozh after the adjacent city now known as Sudak.[1][24] It was known in Ottoman Turkish as the Balük-Denis ("Fish Sea") from its high productivity.[12]

History

Prehistory

There are traces of Neolithic settlement in the area now covered by the sea.

In 1997, William Ryan and Walter Pitman of Columbia University published a theory that a massive flood through the Bosporus occurred in ancient times. They claim that the Black and Caspian Seas were vast freshwater lakes, but in about 5600 BC the Mediterranean spilled over a rocky sill at the Bosporus, creating the current link between the Black and Mediterranean Seas. Subsequent work has been done both to support and to discredit this theory, and archaeologists still debate it. This has led some to associate this catastrophe with prehistoric flood myths.[25]

.svg.png.webp)

Antiquity

The Maeotian marshes around the mouth of the Tanais River (the present-day Don) were famous in antiquity, as they served as an important check on the migration of nomadic people from the Eurasian steppelands. The Maeotians themselves lived by fishing and farming, but were avid warriors able to defend themselves against invaders.[26] Misled by its strong currents,[12] ancient geographers had only a vague idea of the extent of the sea, whose fresh water caused them to typically label it a "swamp" or a "lake". Herodotus (5th century BC) judged it as large as the Black Sea, while the Pseudo-Scylax (4th century BC) thought it about half as large.[16]

It was long believed to provide direct communication with the Arctic Ocean.[12] Polybius (2nd century BC) confidently expected that the strait to the Sea of Azov would close in the near future, due to ongoing deposition of sediments from rivers.[27] In the 1st century, Strabo reckoned the distance from the Cimmerian Bosporus (the Strait of Kerch) to the mouth of the Tanais at 2200 stadia, a roughly correct figure,[29] but did not know that its width continuously narrows.[16]

Milesian colonization began in the 7th century BC. The Bosporan Kingdom was named for the Cimmerian Bosporus rather than for the more famous Bosporus at the other end of the Black Sea. Briefly annexed by Pontus from the late 2nd century BC, it stretched along both southern shores of the Sea of Azov from the time of Greek colonization to the end of the Roman Empire, serving as a client kingdom which exported wheat, fish, and slaves in exchange for Greek and Roman manufactures and luxuries. Its later history is uncertain but probably the Huns, after defeating the Alans people who had settled in the region from central Asia, overran it in the late 4th century.[30]

Azov campaigns of 1695–96 and 1736–37

The Sea of Azov was frequently the scene of military conflicts between Russia, pursuing naval expansion to the south, and the major power in the region, Turkey. During the Russo-Turkish War (1686–1700), there were two campaigns in 1695–96 to capture the then Turkish fortress of Azov defended by a garrison of 7,000. The campaigns were headed by Peter I and aimed to gain Russian access to the Sea of Azov and Black Sea. The first campaign began in the spring of 1695. The Russian army consisted of 31 thousand men and 170 cannons and included selected trained regiments and Cossacks. It reached Azov on 27–28 June and besieged it by land by 5 July. After two unsuccessful assaults on 5 August and 25 September, the siege was lifted.[31]

The second campaign involved both ground forces and the Azov fleet, which was built in Moscow Oblast, Voronezh, Bryansk and other regions between winter 1695 and spring 1696. In April 1696, the army of 75,000 headed by Aleksei Shein moved to Azov by land and by ship via the Don River to Taganrog. In early May, they were joined by another fleet led by Peter I. On 27 May, the Russian fleet blocked Azov by sea. On 14 June, the Turkish fleet tried to break the blockade but, after losing two ships, retreated to the sea. After intensive bombardment of the fortress from land and sea, on 17 July the Russian army broke the defense lines and occupied parts of the wall. After heavy fighting, the garrison surrendered on 17 July. After the war, the Russian fleet base was moved to Taganrog and Azov, and 215 ships were built there between 1696 and 1711. In 1711, as a result of the Russo-Turkish War (1710–1711) and the Treaty of the Pruth, Azov was returned to Turkey and the Russian Azov fleet was destroyed.[31][32] The city was recaptured by Russia in 1737 during the Russo-Austrian-Turkish War (1735–1739). However, as a result of the consequent Treaty of Niš, Russia was not allowed to keep the fortress and military fleet.[33]

Crimean War 1853–1856

Another major military campaign on the Sea of Azov took place during the Crimean War of 1853–56. A naval and ground campaign pitting the allied navies of Britain and France against Russia took place between May and November 1855. The British and French forces besieged Taganrog, aiming to disrupt Russian supplies to Crimea. Capturing Taganrog would also result in an attack on Rostov, which was a strategic city for Russian support of their Caucasian operations. On 12 May 1855, the allied forces easily captured Kerch and gained access to the Sea of Azov, and on 22 May they attacked Taganrog. The attack failed and was followed by a siege. Despite the vast superiority of the allied forces (about 16,000 soldiers against fewer than 2,000), the city withstood all attempts to capture it, which ended around August 1855 with the retreat of the allied army. Individual coastal attacks continued without success and ceased in October 1855.[34]

21st century

In December 2003, Ukraine and the Russian Federation agreed in a treaty to treat the sea and the Kerch Strait as shared internal waters.[35][36]

In September 2018, Ukraine announced the intention to add navy ships and further ground forces along the coast of the Sea of Azov, with the ships based at Berdyansk. The military posturing was exacerbated following the construction of the Crimean Bridge, which is too low to allow passage of Panamax ships into Ukraine’s port.[37] Late that September, two Ukrainian vessels departed from the Black Sea port Odessa, passed under the Crimean Bridge, and arrived in Mariupol.[38] Tensions increased further after the Kerch Strait incident in November 2018, when Russia seized three Ukrainian Navy vessels attempting to enter the Sea of Azov.[39]

Control of the western shore of the Sea is vital to the economy of Ukraine but it is also of immense strategic importance to Russia, as a land route to Crimea as well as it is for passage by Russian marine traffic.[40]

On December 10, 2021, the Ukrainian Navy announced that Russia had blocked off nearly 70 percent of the Sea of Azov, issuing navigation warnings, ostensibly to conduct artillery fire exercises on the sea ..."near Mariupol, Berdyansk and Henichesk."[41] It raised apprehension regarding a potential Russian invasion since it had begun amassing tens of thousands of troops near the southeast Ukraine border and had begun a propaganda war against the Kyiv government.[41] The Russians seized three Ukrainian military vessel as the boats were trying to cross the strait, and captured 24 sailors who were finally released after months of negotiations.[41]

On February 24, 2022, Russian forces began shelling Mariupol at the start of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.[42][43] By May, with the end of the siege of Mariupol, Russia fully captured the city and blocked off Ukraine's access to the sea by controlling the entire north shore.[44]

Geology and bathymetry

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limit of the Sea of Azov in the Kertch Strait [sic] as "The limit of the Black Sea", which is itself defined as "A line joining Cape Takil and Cape Panaghia (45°02'N)".[45]

The sea is considered an internal sea of Russia and Ukraine, and its use is governed by an agreement between these countries ratified in 2003.[46] The sea is 360 kilometres (220 mi) long and 180 kilometres (110 mi) wide and has an area of 39,000 square kilometres (15,000 sq mi); it is the smallest sea within the countries of the former Soviet Union.[47] The main rivers flowing into it are the Don and Kuban; they ensure that the waters of the sea have comparatively low salinity and are almost fresh in places, and also bring in huge volumes of silt and sand. Accumulation of sand and shells results in a smooth and low coastline, as well as in numerous spits and sandbanks.[24]

The Sea of Azov is the shallowest sea in the world with an average depth of 7 metres (23 ft) and maximum depth of 14 metres (46 ft);[1] in the bays, where silt has built up, the average depth is about 1 metre (3 ft). The sea bottom is also relatively flat with the depth gradually increasing from the coast to the centre.[48] The Sea of Azov is an internal sea with passage to the Atlantic Ocean going through the Black, Marmara, Aegean and Mediterranean seas. It is connected to the Black Sea by the Strait of Kerch, which at its narrowest has a width of 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) and a maximum depth of 15 metres (49 ft).[1] The narrowness of the Kerch Strait limits the water exchange with the Black Sea. As a result, the salinity of the Sea of Azov is low; in the open sea it is 10–12 psu, about one third of the salinity of the oceans; it is even lower (2–7 psu) in the Taganrog Bay at the northeast end of the Sea. The long-term variations of salinity are within a few psu and are mostly caused by changes in humidity and precipitation.[49][50]

Although more than 20 rivers flow into the sea, mostly from the north,[48] two of them, the Don and Kuban rivers, account for more than 90% of water inflow. The contribution of the Don is about twice that of the Kuban.[48] The Kuban delta is located at the southeast, on the east side of the Kerch Strait. It is over 100 km long and covers a vast flooded area with numerous channels. Because of the spread, the delta has low contrast in satellite images, and is hardly visible in the map. The Don flows from the north into the large Taganrog Bay. The depth there varies between 2 and 9 metres, while the maximum depth is observed in the middle of the sea.[51]

Typical values of the annual inflow and outflow of water to the sea, averaged over the period from 1923 to 1985, are as follows: river inflow 38.6 km3, precipitation 15.5 km3, evaporation 34.6 km3, inflow from the Black Sea 36–38 km3, outflow 53–55 km3.[52] Thus, about 17 km3 of fresh water is outflowing from the Azov Sea to the Black Sea.[24] The depth of Azov Sea is decreasing, mostly due to the river-induced deposits.[47] Whereas the past hydrological expeditions recorded depths of up to 16 metres, more recent ones could not find places deeper than 13.5–14 metres.[47] This might explain the variation in the maximum depths among different sources. The water level fluctuates by some 20 cm over the year due to the snow melts in spring.[52]

The Taman Peninsula has about 25 mud volcanoes, most of which are active. Their eruptions are usually quiet, spilling out mud, and such gases as methane, carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, but are sometimes violent and resemble regular volcanic eruptions. Some of those volcanoes are under water, near the shores of the peninsula. A major eruption on 6 September 1799, near stanitsa Golubitskaya, lasted about 2 hours and formed a mud island 100 metres in diameter and 2 metres in height; the island was then washed away by the sea. Similar eruptions occurred in 1862, 1906, 1924, 1950 and 1952.[47]

The current vertical profile of the Sea of Azov exhibits oxygenated surface waters and anoxic bottom waters, with the anoxic waters forming in a layer 0.5 to 4 metres (1.6–13.1 ft) in thickness. The occurrence of the anoxic layer is attributed to seasonal eutrophication events associated with increased sedimentary input from the Don and Kuban Rivers. This sedimentary input stimulates biotic activity in the surface layers, in which organisms photosynthesise under aerobic conditions. Once the organisms expire, the dead organic matter sinks to the bottom of the sea where bacteria and microorganisms, using all available oxygen, consume the organic matter, leading to anoxic conditions. Studies have shown that in the Sea of Azov, the exact vertical structure is dependent on wind strength and sea surface temperature, but typically a 'stagnation zone' lies between the oxic and anoxic layers.[53]

Coastal features and major population centres

Many rivers flowing into the Sea of Azov form bays, lagoons and limans. The sand, silt and shells they bring are deposited in the areas of reduced flow, that is the sides of the bays, forming narrow sandbanks called spits. Typical maximum depth in the bays and limans is a few metres. Because of shallow waters and abundant rivers, the spits are remarkably long and numerous in the sea – the Arabat Spit stretches over 112 kilometres (70 mi) and is one of the world's longest spits; three other spits, Fedotov Spit, Achuevsk Spit and Obitochna Spit, are longer than 30 km. Most spits stretch from north to south and their shape can significantly change over just several years.[54][55]

A remarkable feature of the Sea of Azov is the large complex of shallow lagoons called Sivash or "Rotten Sea". Their typical depth is only 0.5–1 metres with a maximum of 3 metres. They cover an area of 2,560 square kilometres (990 sq mi) in the northeastern Crimea which is separated from the sea by the Arabatsk Spit. North of the spit lies the city of Henichesk (population 22,500) and south of it is the Bay of Arabat.[56] Sivash accepts up to 1.5 km3 of Azov water per year. Because of the lagoons' wide extent and shallowness, the water rapidly evaporates, resulting in the high salinity of 170 on the practical salinity scale (i.e. 170 psu). For this reason Sivash has long had an important salt-producing industry.[51]

North of the Arabat Spit is the Molochnyi Liman with the associated Fedotov Spit (45 km long) which are formed by the Molochna River. Farther north, between the Fedotov Spit and Obytochna Spit (30 km long), lies Obytochny Bay. Further north, between Obytochna Spit and Berdyansk Spit (23 km long), is Berdyansk Bay with two cities, Berdyansk (population 112,000) and Primorsk (population 13,900). Further north again lies Belosaraysk Bay with Belosaraysk Spit, formed by the river Kalmius. The major city in the area is Mariupol (population 491,600). Then, approaching the Taganrog Bay and very close to Taganrog, are the Mius Liman and Krivaya Spit formed by the Mius River.[55]

With an area of about 5,600 square kilometres (2,200 sq mi), Taganrog Bay is the largest bay of the Sea of Azov. It is located in the north-eastern part of the Sea and is bounded by the Belosaraysk and Dolgaya Spits. The Don flows into it from the north-east. On its shores stand the two principal cities of the Sea of Azov, Taganrog (population 257,600) and Azov (population 83,200). South-east of the bay is Yeysk Liman. It lies entirely on the continent, entering the Taganrog Bay through the Yeysk and Glafirovsk Spits, and is the mouth of the Yeya River. Yeysk Spit is part of Yeysk city, which has a population of 87,500. It extends into the prominent Yeysk peninsula, which is tipped in the north-west by the Dolgaya Spit. South of it, also enclosed by the continent, lies Beisug Liman, which is restricted by the Yasensk Spit and is fed by the Beysug River. South-west of the liman, the 31 km long Achuevsk Spit runs along the coastline. Between the Achuevsk spit and Beisug Liman stands Primorsko-Akhtarsk with 32,165 inhabitants.[54][55]

In the south, the Sea of Azov is connected to the Black Sea via the Strait of Kerch, which is bordered to the west by the Kerch peninsula of the Crimea and to the east by the Russian Taman peninsula in Krasnodar Krai. The city of Kerch (population 151,300) is located on the Kerch peninsula, and the Taman peninsula contains the delta of the Kuban, a major Russian river. The strait is 41 kilometres long and 4 to 15 kilometres wide. Its narrowest part lies on the Sea of Azov side, restricted by the Chushka Spit which faces southwards in consequence of the outflow from the Azov to the Black Sea.[57]

The Strait of Kerch is spanned by the Crimean Bridge, which was opened in May 2018. This is a major geopolitical issue since shipping vessels over a certain size can not pass under the span.[58] Since then Russia has been accused of interdicting shipping through the Kerch Strait.[59]

Hydrology

- Sivash

- Bay of Arabat

- Taganrog Bay

- Temryuk Bay

- Kazantip Bay

- Berdyansk Bay

- Obytichna Bay

- Taman Bay

- Kerch Strait, connection with Black Sea

Rivers

- Don

- Kuban

- Molochna

- Molochnyi Lyman

- Kalmius

- Malyi Utlyuk, Velykyi Utlyuk

- Utlyuk Estuary

- Atmanai

- Bolhradsky Sivashyk

- Mius

- Mius Estuary

- Yeya

- Yeisk Estuary

- Beysug

- Beysug Estuary

- Berda

- others

Climate

The sea is relatively small and nearly surrounded by land. Therefore, its climate is continental with cold winters and hot and dry summers. In autumn and winter, the weather is affected by the Siberian Anticyclone which brings cold and dry air from Siberia with winds of 4–7 m/s, sometimes up to 15 m/s. Those winds may lower the winter temperatures from the usual −1 to −5 °C to below −30 °C. The mean mid-summer temperatures are 23–25 °C with a maximum of about 40 °C.[51] Winds are weaker in summer, typically 3–5 m/s.[48] Precipitation varies between 312 and 528 mm/year and is 1.5–2 times larger in summer than in winter.[24]

Average water temperatures are 0–1 °C in winter (2–3 °C in the Kerch Strait) and 24–25 °C in summer, with a maximum of about 28 °C on the open sea and above 30 °C near the shores. During the summer, the sea surface is usually slightly warmer than the air.[48] Because of the shallow character of the sea, the temperature usually lowers by only about 1 °C with depth, but in cold winters, the difference can reach 5–7 °C.[48][60]

The winds cause frequent storms, with the waves reaching 6 metres in the Taganrog Bay, 2–4 metres near the southern shores, and 1 metre in the Kerch Strait. In the open sea, their height is usually 1–2 metres, sometimes up to 3 metres. Winds also induce frequent seiches – standing waves with an amplitude of 20–50 cm and lasting from minutes to hours. Another consequence of the winds is water currents. The prevailing current is a counterclockwise swirl due to the westerly and south-westerly winds. Their speed is typically less than 10 cm/s, but can reach 60–70 cm/s for 15–20 m/s winds. In the bays, the flow is largely controlled by the inflow of the rivers and is directed away from the shore.[52] In the Kerch Strait, the flow is normally toward the Black Sea due to the predominance of northern winds and the water inflow from the rivers; its average speed is 10–20 cm/s, reaching 30–40 cm in the narrowest parts.[61] Although the sea is not subject to tidal variation, there are seasonal changes in the observed sea level of up to 10–20 inches (250–510 mm), caused by seasonal variations in river outflows.[62]

The shallowness and low salinity of the sea make it vulnerable to freezing during the winter. Fast ice bands ranging from 7 km in the north to 1.5 km in the south can occur temporarily at any time from late December to mid-March. Several ships were trapped in ice in 2012 when it froze over.[63] The ice thickness reaches 30–40 centimetres (12–16 in) in most parts of the sea and 60–80 cm in the Taganrog Bay.[61] The ice is often unstable and piles up to the height of several metres. Before the introduction of icebreakers, navigation was halted in the winter.[60]

Flora and fauna

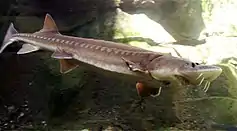

Historically, the sea has had rich marine life, both in variety, with over 80 fish and 300 invertebrate species identified, and in numbers. Consequently, fishing has long been a major activity in the area. The annual catch of recent years was 300,000 tonnes, about half of which are valuable species (sturgeon, pike-perch, bream, sea-roach, etc.).[64] This was partly due to extremely high biological productivity of the sea, which was stimulated by the strong supply of nutrients from numerous rivers feeding the sea, low water salinity, ample heating due to shallow waters and long vegetation period. However, diversity and numbers have been reduced by artificial reduction of river flow (construction of dams), over-fishing and water-intense large-scale cultivation of cotton, causing increasing levels of pollution. Fish hauls have rapidly decreased and in particular anchovy fisheries have collapsed.[1][64][65][66]

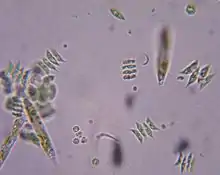

Plankton and benthos

Because of the shallow waters, the development of aquatic life in the Sea of Azov is more characteristic of a lagoon, and the plankton patterns are rather similar in the open sea and near the shores. Despite its shallowness, the water has low transparency, so bottom plants are poorly developed and most algae are of planktonic type. The sea is characterised by high concentrations of organic matter and long blooming periods. Another specific feature of the sea is the variable salinity – low in the large bays and higher in the open sea, especially near the Kerch Strait. Therefore, the plankton species are distributed inhomogeneously in the Sea of Azov. Although many additional species are brought in from the saltier Black Sea, most of them cannot adjust to the variable salinity of the Sea of Azov, except for the euryhaline species.[67] About 600 species of planktonic algae are known in the Sea of Azov.[64] The number of species is dominated by diatoms and green algae; blue-green algae and pyrophites are significant, and euglena and yellow-green algae form only 5% of the species. Green algae are mostly responsible for the colour of the sea in the satellite images (see photos above).[67]

Regarding zooplankton, the fresh waters of the Tanganrog Bay are inhabited by cladocera, copepoda and rotifers, such as Brachionus plicatilis, Keratella curdata and Asplanchna. Western part of the sea, which is more saline, hosts three forms of Acartia clausi, as well as Centropages ponticus, meroplankton and larvae of gastropoda, bivalvia and polychaete.[68]

Benthos species reside mostly at the sea bottom and include worms, crustaceans, bottom protists, coelenterata, and mollusks. Mollusks account for 60–98% of the invertebrate biomass at the Sea of Azov bottom.[68]

Fish

There are 183 ichthyofauna species from 112 genera and 55 families in the Sea of Azov region. Among them, there are 50 rare and 19 endangered species, and the sturgeon Acipenser nudiventris is probably extinct in the region.[69]

The fauna of the freshwater Taganrog Bay is much poorer – it consists of 55 species from 36 genera and 16 families; among them, three species are rare and 6 are endangered.[70]

Flora

The shores of the Sea of Azov contain numerous estuaries and marshes and are dominated by reeds, sedges, Typha and Sparganium. Typical submerged plants are Charales, pond weed, hornworts and water lilies. Also common is sacred lotus.[47] The number of species is large; for example, the Belosaraysk and Berdyansk spits alone contain more than 200 each. Some spits are declared national nature reserves, such as Beglitsk,[71] Belosaraysk,[72] Krivaya[72] and Berdyansk Spits.[55][73][74]

Fauna

Estuaries and spits of the sea are rich in birds, mostly waterfowl, such as wild geese, ducks and seagulls. Colonies of cormorants and pelicans are common. Also frequently observed are swans, herons, sandpipers and many birds of prey. Mammals include foxes, wild cats, hares, hedgehogs, weasels, martens and wild boar.[74] Muskrats were introduced to the area in the early 20th century and are hunted for their fur.[47]

Migrating and invading species

Some ichthyofauna species, such as anchovy, garfish, Black Sea whiting and pickerel, visit the Sea of Azov from the Black Sea for spawning. This was especially frequent in 1975–77 when the salinity of the southern Sea of Azov was unusually high, and additional species were seen such as bluefish, turbot, chuco, spurdog, Black Sea salmon, mackerel and even corkwing wrasse, rock hopper, bullhead and eelpout. Unlike the Black Sea plankton which does not adapt well to the low salinity of the Sea of Azov and concentrates near the Kerch Strait, fishes and invertebrates of the Black Sea adjust well. They are often stronger than the native species, are used to the relatively low temperatures of the Black Sea and survive winter in the Sea of Azov well.[75]

Balanus improvisus is the first benthos species which spread from the Black Sea in the early 20th century and settled in the Sea of Azov. Its current density is 7 kg/m2. From 1956, Rapana venosa is observed in the Sea of Azov, but it could not adjust to low salinity and therefore is limited to the neighborhood of the Kerch Strait. Several Sea of Azov mollusks, such as shipworm (Teredo navalis), soft-shell clam (Mya arernaria), Mediterranean mussel (Mytilus galloprovincialis) and Anadara inaequivalvis, originate from the Black Sea. Another example of invading species is the Dutch crab Rhithropanopeus harrisii which is observed both in saline and freshwater parts.[75]

Formerly three types of dolphins, short-beaked common dolphin, common bottlenose dolphin and harbour porpoise, regularly visited the Sea of Azov from the Black Sea although the common dolphin usually avoided the basin and Kerch Strait due to low salinity.[76] One type of harbour porpoise, Phocoena phocoena relicta, used to live in the Sea of Azov and was therefore called "Azov dolphin" (Russian: азовка) in the Soviet Union. Nowadays, dolphins are rarely observed in the Sea of Azov. This is attributed to shallowing of the sea, increasing navigation activities, pollution, and reduction in the fish population.[77][78]

Various species of pinnipeds and belugas[79] were introduced into Black Sea by mankind and later escaped either by accidental or purported causes. Of these, grey seal has been recorded within Kerch Strait and Sea of Azov.[80] Mediterranean monk seals became extinct in the Black Sea in 1997,[81] and the historic presence of large whales such as minke whales in the Black Sea is recorded,[82][83] although it is unclear whether these mammals historically occurred in the Azov basin.

Economy and ecology

For centuries, the Sea of Azov has been an important waterway for the transport of goods and passengers. The first modern ironworks in Imperial Russia were located upstream on the Kalmius River at Donetsk, originally named Hughesovka (Russian: Юзовка). It was also important for the transportation of iron ores from the mines of the Kerch peninsula to the processing plant of Azovstal in Mariupol (formerly Zhdanov), Ukraine; this activity stopped after the closure of the mines in the 1990s.[84] Navigation increased after the construction in 1952 of the Volga–Don Canal which connected the Sea of Azov with the Volga River – the most important riverine transport route in the central Russia – thus connecting major cities such as Moscow, Volgograd and Astrakhan.[47] Currently, the major ports are in Taganrog, Mariupol, Yeysk and Berdyansk.[24][85]

Increasing navigation rates have resulted in more pollution and even in ecological disasters. On 11 November 2007, a strong storm resulted in the sinking of four ships in the Strait of Kerch, in the Russian Port of Kavkaz. The ships were the Russian bulk carriers Volnogorsk, Nakhichevan, Kovel and the Georgian Haji Izmail with a Turkish crew. Six other ships were driven from their anchors and stranded and two tankers were damaged (Volgoneft-139 and Volgoneft-123). As a result, about 1300 tons of fuel oil and about 6800 tons of sulfur entered the sea.[86][87]

Another traditional activity in the sea is fishing. The Sea of Azov used to be the most productive fishing area in the Soviet Union: typical annual fish catches of 300,000 tonnes converted to 80 kg per hectare of surface. (The corresponding numbers are 2 kg in the Black Sea and 0.5 kilograms (1.1 lb) in the Mediterranean Sea.) The catch has decreased in the 21st century, with more emphasis now on fish farming, especially of sturgeon.

Traditionally much of the coastline has been a zone of health resorts.[48]

The irrigation system of the Taman Peninsula, supplied by the extended delta of the Kuban River, is favorable for agriculture and the region is famous for its vines. The area of the Sivash lagoons and Arabat Spit was traditionally a centre of a salt-producing industry. The Arabat Spit alone produced about 24,000 tonnes/year in the 19th century.[47][56]

References

Citations

- Kostianoy, p. 65

- "Marine Litter Report". www.blacksea-commission.org. Retrieved Jul 29, 2022.

- Adyghe: Хы мыутӏэ, romanized: Xı mıut’ə; Crimean Tatar: Azaq deñizi

- "Sea of Azov". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- "Map of Sea of Azov". worldatlas.com. Retrieved 2015-11-26.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1. 2005. p. 758. ISBN 978-1-59339-236-9.

With a maximum depth of only about 46 feet (14 m), the Azov is the world's shallowest sea

- Academic American encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Grolier. 1996. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-7172-2064-9.

The Azov is the world's shallowest sea, with depths ranging from 0.9 to 14 m (3.0 to 45.9 ft)

- "National Geographic". National Geographic Society. 185: 138. 1994.

- "Earth from space". NASA. Archived from the original on 2011-05-10.

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the world. McFarland. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-7864-2248-7.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-12-30. Retrieved 2015-04-29.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Baynes, T. S., ed. (1878). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (9th ed.). New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 169.

- "Et hoc mare est palus Maeotis famosissima..." (The Opus Majus of Roger Bacon, vol. 1, p. 357); Hofmann, vol. 3, p. 542.

- Carlo Egger Lexicon Nominum Locorum: Supplementum referens nomina Latina vulgaria (1985), p. 42.

- ...Palus Maotis, ovvero Mare Asoviense..." (Il mondo antico, moderno, e novissimo, ovvero Breve trattato ..., vol. 2, p. 767)

-

James, Edward Boucher (1857). "Maeotae and Maeotis Palus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Vol. 2 (1st ed.). London: Walton & Maberly.

James, Edward Boucher (1857). "Maeotae and Maeotis Palus". In Smith, William (ed.). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. Vol. 2 (1st ed.). London: Walton & Maberly. - Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historiæ ["Natural History"], iv.24 & vi.6. (in Latin)

- Avienus. v.32. (in Latin)

- Gaius Valerius Flaccus. Argonautica. iv.720. (in Latin)

- Claud. in Eutrop. i.249. (in Latin)

- Publius Ovidius Naso. Her. vi.107. & Trist. iii.4.49.

- Gell. xvii.8

- Pliny the Elder. Naturalis Historiæ ["Natural History"], vi.7.20.

- "Азовское море" [Sea of Azov]. Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian).

- Ryan, W (1997). "An abrupt drowning of the Black Sea shelf" (PDF). Marine Geology. 138 (1–2): 119. Bibcode:1997MGeol.138..119R. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.598.2866. doi:10.1016/S0025-3227(97)00007-8. S2CID 129316719.

- Strabo. Geographica, xi. (in Latin).

- Polybius. Ἱστορίαι [Historíai, The Histories], iv.39. (in Ancient Greek)

- Strabo. Geographica. Trans. by H.C. Hamilton as The Geography of Strabo, "Preface". George Bell & Sons (London), 1903.

- The length of the stadion varies in Strabo's work depending upon his sources and conversions,[28] but this would have been around 350 to 400 kilometres.

- Sinor, Denis (1990). The Cambridge history of early Inner Asia (2004 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 180. ISBN 0521243041.

- "Azov campaign 1695–96". Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian). Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- "Azov fleet". Great Soviet Encyclopedia (in Russian).

- Sokolov, B. V. Russo-Turkish Wars of 18th–19th Centuries (in Russian).

- Filevsky, Pavel (1898). History of Taganrog. Moscow.

- "Agreement between the Russian Federation and the Ukraine on cooperation in the use of the sea of Azov and the strait of Kerch". www.ecolex.org. Retrieved 2018-11-27.

- McEwan, Alec. "Russia – Ukraine Boundary in the Sea of Azov and Kerch Strait" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 14, 2014.

- Ukraine and Russia Take Their Conflict to the Sea, Stratfor, 2018-09-24

- Dmytro Kovalenko, commander of the Ukrainian Navy move to Azov Sea, Ukrinform (4 October 2018)

- Associated Press (4 December 2018). "Ukraine's ports partially unblocked by Russia, says Kiev". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Russian dominance in the Black Sea: The Sea of Azov, Middle East Institute, Luke Coffey, September 25, 2020. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- Ukraine Says Russia Blocking Most Of Sea Of Azov As Tensions Mount Between Kyiv And Moscow, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, December 11, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2022.

- Vasovic, Aleksandar (24 February 2022). "Port city of Mariupol comes under fire after Russia invades Ukraine". Reuters. Archived from the original on 26 February 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- UN News (24 February 2022) Ukraine Crisis: Protecting civilians 'Priority Number One'; Guterres releases $20M for humanitarian support Archived 1 March 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- "Mariupol has fallen to Russia. Here's what that means for Ukraine". NPR. 19 May 2022.

- "Limits of Oceans and Seas, 3rd edition" (PDF). International Hydrographic Organization. 1953. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 8, 2011. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- Treaty between the Russian Federation and Ukraine on cooperation in the use of the Sea of Azov and Kerch Strait, December 24, 2003, kremlin.ru (in Russian)

- Kapitonov, V. I. Borisov and E. I. (1973). Sea of Azov (in Russian). KKI. Archived from the original on 2010-09-17.

- Zalogin, A. D. Dobrovolsky and B. S. (1982). Seas of USSR (in Russian). Moscow University.

- Kostianoy, pp. 69–73

- "Climatological Atlas of the Sea of Azov". National Oceanographic Data Centre. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- Kostianoy, p. 66

- Kostianoy, p. 67

- Debolskaya, E. I.; Yakusheva, E.V.; Kuznetsov, I.S. (2008). "Analysis of the hydrophysical structure of the Sea of Azov in the period of the bottom anoxia development". Journal of Marine Systems. 70 (3–4): 300. Bibcode:2008JMS....70..300D. doi:10.1016/j.jmarsys.2007.02.027.

- "Complex characteristics of the present condition of the Sea of Azov shore within the Krasnodar Krai" (PDF). www.coruna.coastdyn.ru. Retrieved Jul 29, 2022.

- Lotysh, I.P. (2006). Geography of Kuban. Collegiate Dictionary. Maikop.

- Semenov, Petr Petrovich (1862). Geografichesko-statisticheskìĭ slovar' Rossìĭskoĭ imperìi (Geographical-statistical dictionary of Russian Empire) (in Russian). Oxford University. p. 111.

- Керченский пролив (Kerch Strait) in the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, 1969–1978 (in Russian)

- Peterson, Nolan (31 August 2018). "Russia Opens a New Front in Its War Against Ukraine: the Sea of Azov". The Daily Signal. United States. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

Choursina, Kateryna (25 July 2018). "Ukraine Complains Russia Is Using New Crimea Bridge to Disrupt Shipping". Bloomberg. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

"Putin Opens Crimean Bridge Condemned By Kyiv, EU". Radio Free Europe. 15 May 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

"Putin Inaugurates Bridge to Crimea". The Maritime Executive. 5 May 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2018. - "U.S. Accuses Russia of Harassing Ukrainian Shipping". Maritime Executive. 30 August 2018. Retrieved 1 September 2018.

Sharkov, Damien (31 August 2018). "Russia is Blocked 'Hundreds" of Ships from Ukraine's Ports and the U.S. Wants it to Stop". Newsweek. Retrieved 2 September 2018. - Kostianoy, p. 69

- Kostianoy, p. 68

- "Water level variation". Black Sea Pilot. United States Hydrographic Office. 1927. p. 44.

- "Vessels trapped in ice in Azov sea". www.odin.tc. Retrieved Jul 29, 2022.

- Kostianoy, p. 76

- Kostianoy, p. 86

- Battle, Jessica Lindström (14 February 2004). Alien invaders in our seas. WWF Global. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014.

- Kostianoy, p. 77

- Kostianoy, p. 78

- Kostianoy, p. 79

- Kostianoy, p. 81

- Основные положения о территориальном планировании, содержащиеся в "Схеме территориального планирования рекреационного комплекса прибрежных территорий Азовского моря и Нижнего Дона" (in Russian). Retrieved August 20, 2002.

- "List of nature reserves" (in Russian). Archived from the original on December 22, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2002.

- Basics of ecology (in Russian). Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine. 2005. Archived from the original on April 26, 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2002.

- "Berdyansk Spit" (in Russian). Web Site of Berdyansk. Retrieved August 30, 2002.

- Kostianoy, pp. 83–85

- "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- "Dolphins are leaving the polluted Sea of Azov" (in Russian). Novosti.dn.ua. 19 February 2010.

- Klinowska, M. (1991). Dolphins, porpoises and whales of the world: the IUCN red data book. IUCN. p. 89. ISBN 978-2-88032-936-5.

- Anderson R.. 1992. Black Sea Whale Aided By Activists. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved on April 21. 2016

- "Grey seal Halichoerus grypus in the Black Sea: The first case of long-term survival of an exotic pinniped". www.researchgate.net. Retrieved Jul 29, 2022.

- Karamanlidis, A.; Dendrinos, P. (2015). "Monachus monachus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T13653A45227543. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T13653A45227543.en.

- "Current knowledge of the cetacean fauna of the Greek Seas" (PDF). cetaceanalliance.org. 2003. pp. 219–232. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-09-07. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- "Киты в Черном море (cached)". Archived from the original on 2019-02-03. Retrieved 2021-12-24.

- Hirnycyj encyklopedycnyj slovnyk, Volume 3 (in Ukrainian). Schidnyj Vydavnyčyj Dim. 2004. ISBN 978-966-7804-78-7.

- "Sea of Azov". Britannica. Retrieved August 30, 2002.

- "EU experts to assess ecological situation in Kerch Strait". Web-Portal of the Ukrainian Government. March 18, 2008.

- "Oil Spill Near Black Sea Causes 'Ecological Catastrophe'". Associated Press. November 13, 2007. Archived from the original on September 7, 2008. Retrieved August 30, 2002.

Sources

- Works cited

- Kosarev, Andrey G.; Kostianoy, Aleksey N. (2007). The Black Sea Environment. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-74291-3.