Economy of Hong Kong

The economy of Hong Kong is a highly developed free-market economy. It is characterised by low taxation, almost free port trade and a well-established international financial market.[16][17] Its currency, called the Hong Kong dollar, is legally issued by three major international commercial banks,[18] and is pegged to the US dollar.[19][20] Interest rates are determined by the individual banks in Hong Kong to ensure that they are market driven.[21] There is no officially recognised central banking system, although the Hong Kong Monetary Authority functions as a financial regulatory authority.[22][23]

Central and Victoria Harbour of Hong Kong | |

| Currency | Hong Kong dollar (HKD) |

|---|---|

| 1 April – 31 March | |

Trade organisations | APEC, WTO, Group of Twenty (Chinese delegation), One Belt One Road, AIIB and ICC etc. |

Country group | |

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank |

|

GDP by sector |

|

| 1.6% (2021)[6] | |

Population below poverty line | 19.9% (2016 est.)[7] |

| 53.9 high (2016)[7] | |

Labour force | |

Labour force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment |

|

Main industries | financing and insurance, import and export trade, professional and business services |

Ease-of-doing-business rank | |

| External | |

| Exports | $537.8 billion (2017 est.)[7] |

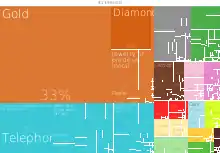

Export goods | electrical machinery and appliances, textiles, apparel, watches and clocks, toys, jewelry, goldsmiths' and silversmiths' wares, and other articles of precious or semi-precious materials[7] |

Main export partners | (2021)[6] |

| Imports | $561.8 billion (2017 est.)[7] |

Import goods | raw materials and semi-manufactures, consumer goods, capital goods, foodstuffs, fuel (most is reexported)[7] |

Main import partners |

|

FDI stock | |

Current account | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

Public debt | 0.1% of GDP (2017 est.)[7] |

Budget balance | +5.2% (of GDP) (2017 est.)[7] |

| Revenues | 79.34 billion (2017 est.)[7] |

| Expenses | 61.64 billion (2017 est.)[7] |

Credit rating | Standard & Poor's:[13] AAA (Domestic) AAA (Foreign) AAA (T&C Assessment) Outlook: Stable[14] Moody's:[14] Aa1 Outlook: Stable Fitch:[14] AA+ Outlook: Stable |

Foreign reserves | US$431 billion (December 2017)[15] |

Its economy is governed under positive non-interventionism, and is highly dependent on international trade and finance. For this reason it is regarded as among the most favorable places to start a company. In fact, a recent study shows that Hong Kong has come from 998 registered start-ups in 2014 to over 2800 in 2018, with eCommerce (22%), Fintech (12%), Software (12%) and Advertising (11%) companies comprising the majority.[24] The Economic Freedom of the World Index listed Hong Kong as the number one territory, with a score of 8.91, in 2019.[25]

Hong Kong's economic strengths include a sound banking system, virtually no public debt, a strong legal system, ample foreign exchange reserves with assets of US$481.6 billion represent over six times the currency in circulation or about 46 per cent of Hong Kong dollar M3 as at the end of March 2022,[26] rigorous anti-corruption measures and close ties with mainland China.[27] The Hong Kong Stock Exchange is a favourable destination for international firms and firms from mainland China to be listed, due to Hong Kong's highly internationalised and modernised financial industry. Additional advantages include the city's capital market in Asia, its size, regulations and available financial tools, which are comparable to London and New York City.[28][29]

Hong Kong's gross domestic product had grown 180 times between 1961 and 1997. Also, the GDP per capita rose by 87 times within the same time frame.[30] Its economy is slightly larger than Israel's or Ireland's[31][32][33] and its GDP per capita at purchasing power parity was the sixth highest globally in 2011. By the latter measure, its GDP per capita was higher than those of the United States and the Netherlands, and slightly lower than Brunei. In 2009, Hong Kong's real economic growth fell by 2.8% as a result of the Great Recession.[34]

By the late 20th century, Hong Kong was the seventh largest port in the world and second only to New York City and Rotterdam in terms of container throughput. Hong Kong is a full Member of the World Trade Organization.[35] The Kwai Chung container complex was the largest in Asia, while Hong Kong shipping owners were second only to those of Greece in terms of total tonnage holdings in the world. The Hong Kong Stock Exchange is the sixth largest in the world, with a market capitalisation of about US$3.732 trillion.[36]

Hong Kong has also had an abundant supply of labour from the regions nearby. A skilled labour force coupled with the adoption of modern British/Western business methods and technology ensured that opportunities for external trade, investment, and recruitment were maximised. Prices and wages in Hong Kong are relatively flexible, depending on the performance and stability of the economy of Hong Kong.[37]

Hong Kong raises revenues from the sale and taxation of land and through attracting international businesses to provide capital for its public finance, due to its low tax policy. According to Healy Consultants, Hong Kong has the most attractive business environment within East Asia, in terms of attracting foreign direct investment (FDI).[38] In 2013, Hong Kong was the third largest recipient of FDI in the world.[39]

Hong Kong ranked fourth on the Tax Justice Network's 2011 Financial Secrecy Index.[40] The Hong Kong Government was the fourth highest ranked Asian government[41] in the World Economic Forum's Network Readiness Index (NRI), a measure of a government's information and communication technologies in 2016, and ranked 13th globally.[42]

Economic predictions

Since the 1997 handover, Hong Kong's economic future became far more exposed to the challenges of economic globalisation and the direct competition from cities in mainland China. In particular, Shanghai claimed to have a geographical advantage. The Shanghai municipal government dreamt of turning the city into China's main economic centre by as early as 2010.[43]

Positive non-interventionism

Hong Kong's economic policy has often been cited by economists such as Milton Friedman and the Cato Institute as an example of laissez-faire capitalism, attributing the city's success to the government having a relatively low level of involvement in the economy. However, others have argued that the economic strategy is not at all adequately characterised by the term laissez-faire.[44] They point out that there are still many ways in which the government is involved in the economy, some of which exceed the degree of involvement in other capitalist countries. For example, the government is involved in public works projects, healthcare, education, and social welfare spending. Further, although rates of taxation on personal and corporate income are low by international standards, unlike most other countries Hong Kong's government raises a significant portion of its revenues from land leases and land taxation. All land in Hong Kong is owned by the government and is leased to private developers and users on fixed terms, for fees which are paid to the state treasury. By restricting the sale of land leases, the Hong Kong government keeps the price of land at what some consider as artificially high prices and this allows the government to support public spending with a low tax rate on income and profit.[45]

Economic freedom

Hong Kong was ranked as the world's 2nd freest economy in the Index of Economic Freedom of The Heritage Foundation in 2020 after Singapore.[46][47] The index measures restrictions on business, trade, investment, finance, property rights and labour, and considers the impact of corruption, government size and monetary controls in 183 economies. Hong Kong is the only economy to have scored 90 points or above on the 100-point scale, achieved in 2014 and 2018.[48] In 2021 the Heritage Foundation removed Hong Kong as a separate entity from China from its list of freest economics of the world citing increasing interference from the Chinese government in Hong Kong's governmental system and democratic process. With this Hong Kong, along with Macao, lost a position they had held in the index since the index's inception in 1995. At the time of the removal from the index, the founder of the Heritage Foundation indicated that while the SARs "offer their citizens more economic freedom than is available to the average citizen of China", these economic policies are still "ultimately controlled from Beijing".[49]

Economic data

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2020 (with IMF staff estimates in 2021–2026). Inflation below 5% is in green.[50]

| Year | GDP PPP

(in Bil. Int$) |

GDP per capita PPP

(in Int$) |

GDP

(in Bil. US$nominal) |

GDP per capita

(in US$ nominal) |

GDP growth

(real) |

Inflation rate

(in Percent) |

Unemployment

(in Percent) |

Government debt

(in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 36.08 | 7130 | 28.8 | 5700 | 11.5% | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | |||||||

| 1982 | n/a | |||||||

| 1983 | n/a | |||||||

| 1984 | n/a | |||||||

| 1985 | n/a | |||||||

| 1986 | n/a | |||||||

| 1987 | n/a | |||||||

| 1988 | n/a | |||||||

| 1989 | n/a | |||||||

| 1990 | n/a | |||||||

| 1991 | 37.4% | |||||||

| 1992 | ||||||||

| 1993 | ||||||||

| 1994 | ||||||||

| 1995 | ||||||||

| 1996 | ||||||||

| 1997 | ||||||||

| 1998 | ||||||||

| 1999 | ||||||||

| 2000 | ||||||||

| 2001 | ||||||||

| 2002 | ||||||||

| 2003 | ||||||||

| 2004 | ||||||||

| 2005 | ||||||||

| 2006 | ||||||||

| 2007 | ||||||||

| 2008 | ||||||||

| 2009 | ||||||||

| 2010 | ||||||||

| 2011 | ||||||||

| 2012 | ||||||||

| 2013 | ||||||||

| 2014 | ||||||||

| 2015 | ||||||||

| 2016 | ||||||||

| 2017 | ||||||||

| 2018 | ||||||||

| 2019 | ||||||||

| 2020 | ||||||||

| 2021 | ||||||||

| 2022 | ||||||||

| 2023 | ||||||||

| 2024 | ||||||||

| 2025 | ||||||||

| 2026 |

GDP[6]

- GDP – nominal (2021): HK$2,869,682 million

- GDP – real growth rate (2021): +6.3%

- GDP – per capita (2021): HK$387,110

- GDP – composition by sector (2020):

- Financial services: 23.4%

- Trading and Logistics: 19.8%

- Professional Services and Other Producer Services: 11.5%

- Tourism: 0.4%

- Other Sectors: 44.9%

Gdp ppp\per capita in $2020 59520, Gdp ppp 444,86milliards\billions dollars[51]

| Economy of Hong Kong |

|---|

| Identity |

|

| Resources |

|

| Companies |

|

| Other Hong Kong topics |

|

|

| Hong Kong Portal |

Population[6]

- Population (2021 year end): ~7.4 million

- Unemployment rate (2021): 5.2%

- Labour Force Participation Rate (2021):

- Overall: 59.4%

- Male: 65.8%

- Female: 54.2%

- Age 15–24: 34.9%

- Age 25–44: 85.9%

- Age 44-64: 68.8%

- Age 65 and over: 12.5%

Labour[6]

- Labour force (2021): 3.87 million -1.2% year-on-year

- Persons Engaged in various sectors (Dec 2021):

- Social and personal services: 537,322

- Import/export trade and wholesale: 439,500

- Professional and business services: 387,702

- Accommodation and food services: 253,527

- Retail: 251,421

- Finance and insurance: 240,274

- Unemployed (2021): 200,300 5.2%

- Underemployed (2021): 98,900 2.6%

2022–23 fiscal year budget[52]

- Total Revenues: HK$715.9 billion

- Total Expenditures: HK$807.3 billion

- Deficit: HK$91.4 billion

- Government debt at 31 March 2022: HK$56.68 billion

Trade[6]

- Selective data in HK$ for Main Countries/Territories (2021)

- Total Trade: $10,268.4 billion +25.3% year-on-year, trade balance -$347.1 billion

- With mainland China: $5,385.4 billion (52.4% share), +26.8% year-on-year

- With Taiwan: $691.3 billion (6.7% share), +37.1% year-on-year

- With USA: $516.3 billion (5.0% share), +19.1% year-on-year

- Imports: $5,307.8 billion +24.3% year-on-year

- From mainland China: $2,433.4 billion (45.8% share), +26.5% year-on-year

- From Taiwan: $547.5 billion (10.3% share), +35.0% year-on-year

- From Singapore: $413.8 billion (7.8% share), +31.7% year-on-year

- Exports: $4,960.6 billion +26.3% year-on-year

- To mainland China: $2,951.9 billion (59.5% share), +27.0% year-on-year

- To USA: $309.6 billion (6.2% share), +19.6% year-on-year

- To Taiwan: $143.8 billion (2.9% share), +46.0% year-on-year

Trade with Macau

As at 2015, Macau is Hong Kong's second largest export destination, occupying 6.1% of Hong Kong's total exports.[54] The amount of export totaled US$8.4B, with broadcasting equipment, jewelry, and precious metal watches as the major products.[55] On the other hand, Hong Kong is Macau's largest export destination.[56] Totaled USD 774M, with precious metal watches, jewelry, trunks and cases as the major trading products, the exports to the Hong Kong forms 53% of Macau's total exports.[57] Since 2018, Hong Kong and Macau have been connected via road by the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge.

Poverty

The international poverty line is a monetary threshold under which an individual is considered to be living in poverty. This threshold is calculated using Purchasing Power Parity.[58] According to the World Bank, the international poverty line was most recently updated in October 2015, in which it was increased from $1.25 per day to $1.90 per day using the value of 2011 dollars.[59] Raising this threshold helps account for changes in costs of living, which directly effects individuals ability to obtain basic necessities across countries.

Recent figures show that 1.37 million people are living below the poverty line and struggling to survive on HK$4,000 (US$510) per month for a one-person household, HK$9,800 for a two-person household earning, and HK$15,000 or a three-person household.[60] The poverty rate in Hong Kong hit a high of 20.1%, but recent efforts by government programs have lowered this number to 14.7%.[61]

In December 2012, the Commission on Poverty (CoP) was reinstated to prevent and alleviate poverty with three primary functions; analyze the poverty situation, assist policy formulation and to assess policy effectiveness. Cash handouts have been credited with alleviating much of the poverty, but the extent in which poverty has been alleviated is still questionable. Although cash handouts raise households above the poverty line, they are still struggling to meet certain standards as the cost of living in Hong Kong steadily increases.

Coupled with these cash payments, statutory minimum wage is set to increase for a second time in the past 10 years. Statutory Minimum Wage (SMW) came into existence on 1 May 2011 and the SMW rate has been HK$34.5 per hour since May 2017. The Legislative Council in Hong Kong most recently approved the revision on the SMW rate to increase to HK$37.5 per hour, effective 1 May 2019.[62] Although the total statistics for Hong Kong show declining poverty, child poverty has recently increased .3 percentage points, up to a total of 23.1%, as a result of larger households due to children staying with their elderly parents.[63] With economic growth projected to slow in the coming years, poverty becomes an increasingly pressing issue.

Beyond benefiting the younger generation through cash handouts and minimum wage increases, expanded elderly allowances have been implemented to increase disposable incomes of the elderly population that can no longer work. As of 1 February 2019 the amount payable per month for eligible elderly population became HK$1,385 in an effort to raise households incomes living with elderly tenants. Although Hong Kong has become one of the largest growing cities in the world, much of the population is struggling to keep up with the rising costs of living.

One of the largest issues affecting low income families is the availability of affordable housing. Over the past decade, residential Hong Kong property prices have increased close to 242%, with growth finally starting to decelerate in 2019.[64] Considering housing is a basic necessity, prices have continuously increased while disposable incomes remain virtually unchanged. As the amount of affordable housing diminishes, it has become much harder for families to find homes in their home country. Public housing programs have been implemented by the government, but delayed construction and growing waitlists have not helped to the extent they planned for. Recent results from a Hong Kong think tank show that by 2022, the average citizen could wait up to 6 years for public housing.[65] Evidence shows that the availability of affordable housing has declined, forcing households to spend more on shelter and less on other necessities. These issues can lead to worse living conditions and imbalanced diets, both of which pose problems beyond just financial well-being.

Stock exchange

The Hong Kong Stock Exchange is the sixth largest in the world, with a market capitalisation of about US$3.732 trillion as of mid-2017. In 2006, the value of initial public offerings (IPO) conducted in Hong Kong was second highest in the world after London.[66] In 2009, Hong Kong raised 22 percent of IPO capital, becoming the largest centre of IPOs in the world.[67] The exchange is the world's 10th largest by turnover and third largest in China.[68]

See also

- Mainland and HK Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA)

- Mainland and Macau Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement (CEPA)

- Economy of China

- Manufacturing in Hong Kong

- Economy of East Asia

- Individual Visit Scheme

- John James Cowperthwaite

- Positive non-interventionism

- The Hongs

- Taiwan Miracle

- Poverty Campaign: Speak Up

- Seamen's strike of 1922

- Nylonkong

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 21 December 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 28 October 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Population, total". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 16 August 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 30 July 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "List of All Statistical Products". Census and Statistics Department.

- "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- Nations, United. "Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI)". Human Development Reports. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Labor force, total – Hong Kong SAR, China". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 14 August 2019. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Archived from the original on 24 August 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- "Ease of Doing Business in Hong Kong SAR, China". Doingbusiness.org. Archived from the original on 7 February 2017. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2011.

- Rogers, Simon; Sedghi, Ami (15 April 2011). "How Fitch, Moody's and S&P rate each country's credit rating". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 1 August 2013. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- "International Reserves and Foreign Currency Liquidity – Hong Kong". International Monetary Fund. 5 May 2011. Archived from the original on 25 September 2011. Retrieved 31 May 2011.

- Mizuoka, Fujio (2018). Contrived Laissez-Faireism: The Politico-Economic Structure of British Colonialism in Hong Kong. Springer Publishing. p. 26. ISBN 978-3319697932. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- "The Profitability of the Banking Sector in Hong Kong" (PDF). Hkma.gov.hk. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Legal Tender Notes Issue Ordinance Archived 3 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Legislation.gov.hk (30 June 1997)

- "Monetary Stability" (PDF). Hkma.gov.hk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- "Triennial Central Bank Survey of Foreign Exchange and Derivatives Market Activity in April 2007" (PDF). Triennial Central Bank Survey 2007. Bank for International Settlements: 7. September 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2010.

- Gough, Neil; Sang-Hun, Choe (19 July 2012). "Asian Financial Regulators Examine Local Lending Rates". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2017.

- "The Hong Kong Association of Banks". Hkab.org.hk. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- Chiu, Peter (2003). "Hong Kong's Banking Industry Facing Keen Competition". China Perspectives. 2003 (2). doi:10.4000/chinaperspectives.260. Archived from the original on 14 May 2013. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- WHub (2018). "Hong Kong Start Up Ecosystem Whitepaper". Archived from the original on 17 September 2018.

- "Economic Freedom". Fraser Institute. 22 December 2016.

- "Hong Kong's latest foreign currency reserve assets figures released".

- "Hong Kong". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- "London retains financial services crown". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2013.

- "The Global Financial Centres Index 13" (PDF). Zyen.com. March 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 27 July 2018.

- Rikkie Yeung (2008). Moving Millions: The Commercial Success and Political Controversies of Hong Kong's Railways. Hong Kong University Press. ISBN 978-962-209-963-0.

- "Nominal GDP list of countries. Data for the year 2010". World Economic Outlook Database, September 2011. International Monetary Fund. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- "Gross domestic product (2009)" (PDF). The World Bank: World Development Indicators database. World Bank. 27 September 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 September 2009. Retrieved 5 October 2010.

- Field listing – GDP (official exchange rate) Archived 4 October 2008 at the Wayback Machine, The World Factbook

- "GDP growth (annual %)". World Bank. Archived from the original on 10 December 2019. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- Hong Kong, China – Member information Archived 21 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. WTO. Retrieved 1 November 2012.

- "World's Largest Stock Exchanges December 2017". Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- Hong Kong Monetary Authority (30 December 2009). "A Structural Investigation into the Price and Wage Dynamics in Hong Kong" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 June 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- "Hong Kong Company Formation". Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- "UNCTAD World Investment Report". UNCTAD. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- "2011 Results – Financial Secrecy Index". Archived from the original on 28 August 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- After Singapore, S. Korea and Taiwan

- "Global Information Technology Report 2016". World Economic Forum. Archived from the original on 17 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Richardson, Harry W. Bae, Chang-Hee C. (2005) Globalization and Urban Development: Advances in Spatial Science ISBN 3-540-22362-2

- Journal of Contemporary China (2000), 9(24) 291–308 "New Interventionism in the Making: interpreting state interventions in Hong Kong after the change of sovereignty" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2008. Retrieved 12 December 2006.

- Geocities. "Doesn't Hong Kong show the potentials of 'free market' capitalism?". Archived from the original on 20 October 2009. Retrieved 9 October 2010.

- "Index of Economic Freedom". Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- "The World's Freest Economy Is Also Its Least-Affordable Housing Market". Bloomberg BusinessWeek. 21 January 2014. Archived from the original on 25 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- "2014 Index of Economic Freedom – Hong Kong". The Heritage Foundation. Archived from the original on 1 October 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- Feulner, Edwin J. (5 April 2021). "Hong Kong Is No Longer What It Was". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". IMF. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- "Hong Kong GDP per capita based on PPP, 1980-2020". knoema.com. 6 April 2021. Retrieved 27 August 2022.

- "The 2022–23 Budget – Government Revenue and Expenditure". budget.gov.hk.

- "Provisional financial results for the year ended March 31, 2022".

- Where does Hong Kong export to? (2015)

- What does Hong Kong export to Macao? (2015)

- Where does Macau export to? (2015)

- What does Macau export to Hong Kong? (2015)

- Kenton, Will. "International Poverty Line". Investopedia. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "FAQs: Global Poverty Line Update". World Bank. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Record 1.37 million people living below poverty line in Hong Kong". South China Morning Post. 19 November 2018. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Analysis of poverty situation in Hong Kong in 2017 announced (with photo/video)". info.gov.hk. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- "Labour Department – Employee Rights and Benefits". labour.gov.hk. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- hermesauto (20 November 2018). "In Hong Kong, one in five are living in poverty". The Straits Times. Archived from the original on 18 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Guide, Global Property (6 March 2019). "Investment Analysis of Hong Kong Real Estate Market". Global Property Guide. Archived from the original on 19 April 2019. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Chan, Holmes (18 April 2019). "By 2022, average Hongkonger could wait 6 years or more for public housing, think tank warns". Hong Kong Free Press HKFP. Retrieved 18 April 2019.

- Hong Kong surpasses New York in IPOs Archived 9 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine, International Herald Tribune, 25 December 2006. Retrieved 20 January 2007.

- "Hong Kong IPOs May Raise Record $48 Billion in 2010, E&Y Says". Bloomberg L.P. 21 December 2009. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2017.

- After Shenzhen and Shanghai

External links

- Hong Kong Economy

- Hong Kong Government

- Hong Kong Economic Structure, The Economist, 10 January 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- The Hong Kong Experiment by Milton Friedman

- Economic History of Hong Kong Catherine R. Schenk, University of Glasgow

- Hong Kong Census and Statistics Department

- Hong Kong Forex Nows (IBTimes HK)

- World Bank Summary Trade Statistics Hong Kong

- Tariffs applied by Hong Kong as provided by ITC's Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements