Florence Baptistery

The Florence Baptistery, also known as the Baptistery of Saint John (Italian: Battistero di San Giovanni), is a religious building in Florence, Italy, and has the status of a minor basilica.[1] The octagonal baptistery stands in both the Piazza del Duomo and the Piazza San Giovanni, across from Florence Cathedral and the Campanile di Giotto.

The Baptistery is one of the oldest buildings in the city, constructed between 1059 and 1128 in the Florentine Romanesque style. Although the Florentine style did not spread across Italy as widely as the Pisan Romanesque or Lombard styles, its influence was decisive for the subsequent development of architecture, as it formed the basis from which Francesco Talenti, Leon Battista Alberti, Filippo Brunelleschi, and other master architects of their time created Renaissance architecture. In the case of the Florentine Romanesque, one can speak of "proto-renaissance",[2] but at the same time an extreme survival of the late antique architectural tradition in Italy, as in the cases of the Basilica of San Salvatore, Spoleto, the Temple of Clitumnus, and the church of Sant'Alessandro in Lucca.

The Baptistery is renowned for its three sets of artistically important bronze doors with relief sculptures. The south doors were created by Andrea Pisano and the north and east doors by Lorenzo Ghiberti.[3] Michelangelo dubbed the east doors the Gates of Paradise.

The Italian poet Dante Alighieri and many other notable Renaissance figures, including members of the Medici family, were baptized in this baptistery.[4]

The building contains the monumental tomb of Antipope John XXIII, by Donatello.

History

Early history

It was once believed that the Baptistery was originally a Roman temple dedicated to Mars,[5] the tutelary god of the old Florence. The chronicler Giovanni Villani reported this medieval Florentine legend in his 14th-century Nuova Cronica on the history of Florence.[6] Excavations in the 20th century have shown that there was a 1st-century Roman wall running through the piazza with the Baptistery, which may have been built on the remains of a Roman guard tower on the corner of this wall, or possibly another Roman building including a second-century house which was restored in the late 4th or early 5th century.[7][lower-alpha 1] It is certain that an initial octagonal baptistery was erected here in the late 4th or early 5th century. It was replaced or altered by another early Christian baptistery in the 6th century. Its construction is attributed to Theodolinda, queen of the Lombards (570–628), to seal the conversion of her husband, King Authari.

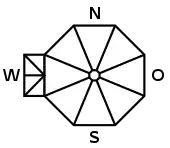

Octagonal design

The octagon had been a common shape for baptisteries for many centuries since early Christian times. Other early examples are the Lateran Baptistery (440) that provided a model for others throughout Italy, the Church of the Saints Sergius and Bacchus (527–536) in Constantinople and the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna (548).

The earlier baptistery was the city's second basilica after San Lorenzo, outside the northern city wall, and predates the church Santa Reparata. It was first recorded as such on 4 March 897, when the Count Palatine and envoy of the Holy Roman Emperor sat there to administer justice. The granite pilasters were probably taken from the Roman forum sited at the location of the present Piazza della Repubblica. At that time, the baptistery was surrounded by a cemetery with Roman sarcophagi, used by important Florentine families as tombs (now in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo).

Construction

The present much bigger Baptistery was built in Romanesque style around 1059, evidence of the growing economic and political importance of Florence. It was reconsecrated on 6 November 1059 by Pope Nicholas II, a Florentine. According to legend, the marbles were brought from Fiesole, conquered by Florence in 1078. Other marble came from ancient structures. The construction was finished in 1128.

An octagonal lantern was added to the pavilion roof around 1150. It was enlarged with a rectangular entrance porch in 1202, leading into the original western entrance of the building, that in the 15th century became an apse, after the opening of the eastern door facing the western door of the cathedral by Lorenzo Ghiberti. On the corners, under the roof, are monstrous lion heads with a human head under their claws. They are early representations of Marzocco, the heraldic Florentine lion (the symbol of Mars, the god of war, the original male protector of Florentia, protecting a lily or iris, the symbol of the original female patron of the town, Flora, the fertile agricultural earth goddess).

Between the fourteenth and sixteenth centuries, three bronze double doors were added, with bronze and marble statues above them. This gives an indication that the Baptistery, at that time, was at least equal to the neighbouring cathedral in importance.

Exterior

Design

The Baptistery has eight equal sides with a scarsella, an apse expanding out of the west side. The sides, originally constructed in sandstone, are clad in geometrically patterned, colored marble, white Carrara with green Prato marble inlay, reworked in Romanesque style between 1059 and 1128. The style of this church would serve as a prototype, influencing many architects, such as Leone Battista Alberti, in their design of Renaissance churches in Tuscany.

The exterior is also ornamented with a number of artistically significant statues by Andrea Sansovino (above the Gates of Paradise), Giovan Francesco Rustici, Vincenzo Danti (above the south doors) and others.

The design work on the sides is arranged in groupings of three, starting with three distinct horizontal sections. The middle section features three blind arches on each side, each arch containing a window. These have alternate, pointed and semicircular tympani. Below each window is a stylized arch design. In the upper fascia, there are also three small windows, each one in the center block of a three-panel design.

The apse was originally semicircular, but rebuilt in a rectangular shape in 1202.

Baptistery doors

Andrea Pisano

As recommended by Giotto to the Arte di Calimala (Cloth Merchants Guild), the guild who had the patronage of the Baptistry, Andrea Pisano was awarded the commission to design the first set of doors in 1329. An antetype for the doors was probably the San Ranieri Gate of the Pisa Cathedral, done by Bonanno Pisano around 1180. The wax model and the gilding at the end was the work of Andrea Pisano, whereas the bronze-casting was executed by Venetian masters, for whom these monumental doors nevertheless were a difficult challenge; it took six years to complete the doors.[8] The gate wings consist of 28 quatrefoil panels altogether, with twenty top panels depicting scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist. The eight lower panels represent the eight virtues of hope, faith, charity (the three theological virtues), humility, fortitude, temperance, justice and prudence (the four cardinal virtues). The south doors were originally installed in 1336 on the east side, facing the Duomo, and were transferred to their present location in 1452.Ref? Lorenzo Ghiberti moulded reliefs for the adjusted doorcase. There is a Latin inscription on top of the door: Andreas Ugolini Nini de Pisis me fecit A.D. MCCCXXX ("Andrea Pisano made me in 1330").

The group of bronze statues above the gate depict The Beheading of St John the Baptist. It is the masterwork of Vincenzo Danti from 1571.

Lorenzo Ghiberti

In 1401, a competition was announced by the Arte di Calimala to design the doors of the east side of the baptistery facing the cathedral, which lasted there for 25 years, before they would eventually be moved to the north side and to be replaced by Ghiberti's second commission, known as the Gates of Paradise.[9][10]

These north doors would serve as a votive offering to celebrate the sparing of Florence from relatively recent scourges such as the Black Death in 1348. Many artists competed for this commission and a jury selected seven semi-finalists. These finalists include Lorenzo Ghiberti, Filippo Brunelleschi and Jacopo della Quercia, with 21-year-old Ghiberti winning the commission. At the time of judging, only Ghiberti and Brunelleschi were finalists, and when the judges could not decide, they were assigned to work together on them. Brunelleschi's pride got in the way, and he went to Rome to study architecture leaving Ghiberti to work on the doors himself. Ghiberti's autobiography, however, claimed that he had won, "without a single dissenting voice." The original designs of The Sacrifice of Isaac by Ghiberti and Brunelleschi are on display in the museum of the Bargello.

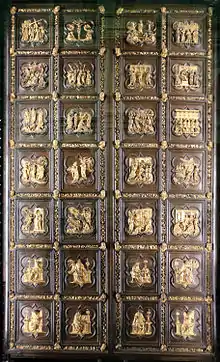

It took Ghiberti 21 years to complete these doors. These gilded bronze doors consist of twenty-eight panels, with twenty panels depicting the life of Christ from the New Testament. The eight lower panels show the four evangelists and the Church Fathers Saint Ambrose, Saint Jerome, Saint Gregory and Saint Augustine. The panels are surrounded by a framework of foliage in the door case and gilded busts of prophets and sibyls at the intersections of the panels. Originally installed on the east side, in place of Pisano's doors, they were later moved to the north side. They are described by the art historian Antonio Paolucci as "the most important event in the history of Florentine art in the first quarter of the 15th century".[11]

The bronze statues over the northern gate depict John the Baptist preaching to a Pharisee and Sadducee. They were sculpted by Francesco Rustici and are superior to any sculpture he did before. Leonardo da Vinci is said not only to have given him technical advice, Leonardo never left him during the whole process from the modelling to the casting;[12] the pose of John the Baptist resembles that of Leonardo's depiction of the prophet.[13]

Ghiberti was now widely recognized as a celebrity and the top artist in this field. He was showered with commissions, even from the pope. In 1424 he received a second commission, this time for the east doors of the baptistery,[14] on which he and his workshop (including Michelozzo and Benozzo Gozzoli) toiled for 27 years, excelling themselves. These had ten panels depicting scenes from the Old Testament, and were in turn installed on the east side. The panels are large rectangles and are no longer embedded in the traditional Gothic quatrefoil, as in the previous doors. Ghiberti employed the recently discovered principles of perspective to give depth to his compositions. Each panel depicts more than one episode. In "The Story of Joseph" is portrayed the narrative scheme of Joseph Cast by His Brethren into the Well, Joseph Sold to the Merchants, The merchants delivering Joseph to the pharaoh, Joseph Interpreting the Pharaoh's dream, The Pharaoh Paying him Honour, Jacob Sends His Sons to Egypt and Joseph Recognizes His Brothers and Returns Home. According to Vasari's Lives, this panel was the most difficult and also the most beautiful. The figures are distributed in very low relief in a perspective space (a technique invented by Donatello and called rilievo schiacciato, which literally means "flattened relief"). Ghiberti uses different sculptural techniques, from incised lines to almost free-standing figure sculpture, within the panels, further accentuating the sense of space.

The panels are included in a richly decorated gilt framework of foliage and fruit, many statuettes of prophets and 24 busts. The two central busts are portraits of the artist and of his father, Bartolomeo Ghiberti.

Although the overall quality of the casting is exquisite, some mistakes have been made. For example, in panel 15 of the north doors (Flagellation) the casting of the second column in the front row has been mistakenly overlaid over an arm, so that one of the flagellators looks trapped in stone, with his hand sticking out of it.[15]

Michelangelo referred to these doors as fit to be the Gates of Paradise (Porte del Paradiso), and they are still invariably referred to by this name.[16] Giorgio Vasari described them a century later as "undeniably perfect in every way and must rank as the finest masterpiece ever created". Ghiberti himself said they were "the most singular work that I have ever made".

Preservation of original art

The Gates of Paradise situated in the Baptistery are a copy of the originals, substituted in 1990 to preserve the panels after over five hundred years of exposure and damage. To protect the original panels for the future, the panels are being restored and kept in a dry environment in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, the museum of the Duomo's art and sculpture. Some of the original panels are on view in the museum; the remaining original panels are being restored and cleaned using lasers in lieu of potentially damaging chemical baths. Three original panels made a US tour in 2007-2008, and then were reunited in a frame and hermetically sealed with the intention of making the panels appear in the context of the doors for public viewing.[17]

Several copies of the doors are held throughout the world. One such copy is held at Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York.[18] Another copy, made in the 1940s, is installed in Grace Cathedral, in San Francisco; copies of the doors are also crafted for the Kazan Cathedral in Saint Petersburg, Russia; the Harris Museum in Preston, United Kingdom;[19] and in 2017 for the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art[20] in Kansas City, Missouri.

Other contributors

The two porphyry columns on each side of the Gates of Paradise were plundered by the Pisans in Majorca and given in gratitude to the Florentines in 1114 for protecting their city against Lucca while the Pisan fleet was conquering the island.

The Gates of Paradise are surmounted by a (copy of a) group of statues portraying the Baptism of Christ by Andrea Sansovino. The originals are in the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo. He then left for Rome to work on a new commission, leaving these statues unfinished. Work on these statues was continued much later in 1569 by Vincenzo Danti, a sculptor from the school of Michelangelo. At his death in 1576 the group was almost finished. The group was finally completed with the addition of an angel by Innocenzo Spinazzi in 1792.

Panels

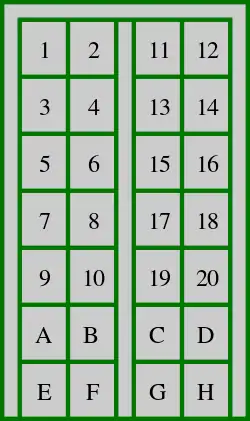

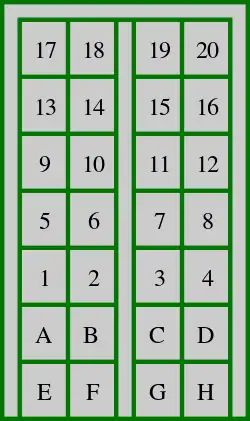

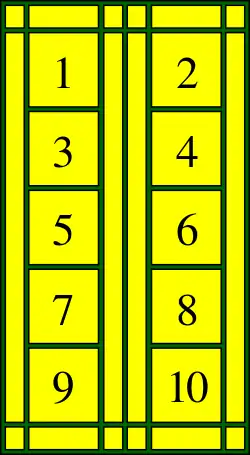

South doors (Andrea Pisano):

|

North doors (Lorenzo Ghiberti):

|

East doors, the Gates of Paradise (Lorenzo Ghiberti):

|

Images from the doors

Reproduction examples in situ

Gates of Paradise, Self-portrait bust of artist

Gates of Paradise, Self-portrait bust of artist Gates of Paradise, The Story of Adam and Eve (copy at the Baptistery)

Gates of Paradise, The Story of Adam and Eve (copy at the Baptistery)_01.JPG.webp) Gates of Paradise, The Story of Abraham

Gates of Paradise, The Story of Abraham Gates of Paradise, The Story of Joseph (copy at the Baptistery)

Gates of Paradise, The Story of Joseph (copy at the Baptistery)

Interior

The interior, which is rather dark, is divided into a lower part with columns and pilasters and an upper part with a walkway. The Florentines spared neither trouble nor expense in decorating the baptistery. The interior walls are clad in dark green and white marble with inlaid geometrical patterns. The niches are separated by monolithic columns of Sardinian granite. The marble revetment of the interior was begun in the second half of the eleventh century.

The building contains the monumental tomb of Antipope John XXIII by Donatello and Michelozzo Michelozzi. A gilt statue, with the face turned to the spectator, reposes on a deathbed, supported by two lions, under a canopy of gilt drapery. He had bequeathed several relics and his great wealth to this baptistery. Such a monument with a baldachin was a first in the Renaissance.

The mosaic marble pavement was begun in 1209. The geometric patterns in the floor are complex. Some show us oriental zodiac motifs, such as the slab of the astrologer Strozzo Strozzi. There was an octagonal font, its base still clearly visible in the middle of the floor. This font, which once stood in the church of Santa Reparata, was installed here in 1128. Dante is said to have broken one of the lower basins while rescuing a child from drowning. The font was removed in 1571 on orders from the grand duke Francesco I de' Medici. The present, and much smaller, octagonal font stands near the south entrance. It was installed in 1658 but is probably much older. The reliefs are attributed to Andrea Pisano or his school.

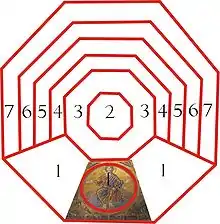

Mosaic ceiling

The Baptistery is crowned by a magnificent mosaic ceiling. It was created over the course of a century in several different phases. The oldest parts are the upper zone of the dome with the hierarchy of angels (2,3), the Last Judgment on the three western segments of the dome (1) and the mosaic above the rectangular chapel on the western side. An inscription in the mosaic above the western rectangular chapel states the date of the beginning of the work and the name of the artist. According to this inscription, work on the mosaic began in 1225 by the Franciscan friar Jacobus. The artist was previously falsely identified to be the Roman mosaicist Jacopo Torriti, who was active around 1300. In accordance with his style, Jacobus was trained in Venice and strongly influenced by the Byzantine art of the early to mid-thirteenth century. Since the inscription also names Emperor Frederick II, the inscription and the completion of the first phase of mosaics must fall within the Ghibelline phase of Florentine rule between 1238 and 1250.[21]

The Last Judgment, created by Jacobus and his workshop, was the largest and most important spiritual image created in the Baptistery. It shows a gigantic majestic Christ and angels with the instruments of the passion at each side (formerly attributed to the painter Coppo di Marcovaldo), the rewards of the saved leaving their tomb in joy (at Christ's right hand), and the punishments of the damned (at Christ's left hand). This last part is particularly famous: evil doers are burnt by fire, roasted on spits, crushed with stones, bitten by snakes, gnawed and chewed by hideous beasts.

The other scenes on the lower zones of the five eastern sections of the dome depict different stories in horizontal tiers of mosaic: (starting at the top) stories from the Book of Genesis; stories of Joseph; stories of Mary and the Christ and finally in the lower tier, stories of Saint John the Baptist, patron saint of the church. A total of sixty pictures originated in the last decade of the thirteenth century. The key artists employed were Corso di Buono and Cimabue. It is the most important narrative cycle of Florentine art before Giotto.[21]

In the drum under the dome many heads of prophets are depicted. Some chapels of the gallery are also decorated with mosaic. These parts were executed around 1330 by mosaicists from Siena.

See also

- History of medieval Arabic and Western European domes

References

Footnotes

- Some of these relics, including the guard tower and the impluvium of the house, are on display at the National Archaeological Museum, Florence[7]

Citations

| External video | |

|---|---|

- "Basilica of St. John". GCatholic.org. Retrieved 9 March 2020.

- Weigert, Hans (1961). Busch, Harald; Lohse, Bernd (eds.). Buildings of Europe: Renaissance Europe. New York: The Macmillan Company. p. 4.

- Florence and Central Italy, 1400–1600 A.D., Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Liukkonen, Petri. "Dante Alighieri". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 17 August 2008.

- "Baptistery of Florence". Museums in Florence. Archived from the original on 6 July 2012. Retrieved 3 September 2020.

- Villani, I.42.

- Toker, Franklin (1976). "A Baptistery below the Baptistery of Florence". The Art Bulletin. 58 (2): 157–167. doi:10.2307/3049493. ISSN 0004-3079. JSTOR 3049493.

- Antonio Paolucci (1996), The Origins of Renaissance Art: The Baptistery Doors, Florence, George Braziller Inc., New York, ISBN 0807614130, p. 8-9

- Paolucci (1996), p. 11

- See Laurie Schneider Adams, Italian Renaissance Art, Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 2001, p. 60. Actually, at the time of the 1401 competition the Florence baptistery needed two portals to be decorated. The aim of the 1401-02 competition was to begin work on this project. See also Monica Bowen, "Ghiberti's North Doors," from Alberti's Window, July 24, 2010.

- Paolucci (1996), p.??

- Vasari cited in Paolucci (1996), p. 22, ann. 1

- Decker, Heinrich (1969) [1967]. The Renaissance in Italy: Architecture • Sculpture • Frescoes. New York: The Viking Press. p. 26.

- Edgerton, Samuel Y. (2009). The Mirror, the Window & the Telescope: How Renaissance Linear Perspective Changed Our Vision of the Universe. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-8014-4758-7.

- Julian Bell (2007). Mirror of the World: A New History of Art (1st paperback ed.). Thames & Hudson. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-500-28754-5.

It is noticeable nonetheless that the casting of one column has been mistakenly overlaid over a flagellator's arm, as it were trapping his hand.

(dead link 29 July 2020) - Coughlan, Robert (1966). The World of Michelangelo: 1475–1564. et al. New York: Time-Life Books. p. 36.

- Vogel, Carol (16 October 2006). "One of Florence's Renaissance Prizes to Go on U.S. Tour". New York Times.

- "Plaster Casts - Vassar College Encyclopedia - Vassar College". vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu. Retrieved 15 April 2021.

- Buchanan, Alan (16 October 2019). "Architecture of the Harris building". The Harris. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- "Gates of Paradise to be Installed at Nelson-Atkins". Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. 28 January 2017. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- Schwarz, Michael Viktor (1 January 1997). Die Mosaiken des Baptisterium in Florenz: Drei Studien zur Florentiner Kunstgeschichte. Cologne: Böhlau-Verlag GmbH. p. 171. ISBN 9783412106966. OCLC 931181326.

- "Brunelleschi & Ghiberti, The Sacrifice of Isaac". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 5 April 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

Further reading

- Wirtz, Rolf C. (2005). Kunst & Architectur, Florenz. Tandem verlag.

- Jepson, Tim. The National Geographic Traveler. Florence & Tuscany. National Geographic Society.

- Montrésor, Carlo (2000). The Opera del Duomo Museum in Florence. Mandragora.

- Clark, Kenneth; David Finn. The Florence Baptistry Doors.

- Radke, Gary. The Gates of Paradise: Lorenzo Ghiberti's Renaissance Masterpiece (High Museum of Art Series).

- Mayer, Yakov Z. "Crying at the Florence Baptistery Entrance: A Testimony of a Traveling Jew". Renaissance Studies Vol. 33 No. 3 2018.

- Walks in Florence on the private travel guide Florin.ms with detailed text

- Over-saturated pictures of the Gates of Paradise with rather clumsy roll-over visual reference, with identifications and details

- The Baptistery of Florence on MuseumsinFlorence.com, a private travel guide of German origin