Bellerophon

Bellerophon (/bəˈlɛrəfən/; Ancient Greek: Βελλεροφῶν) or Bellerophontes (Βελλεροφόντης)[lower-alpha 1], born as Hipponous,[2] was a hero of Greek mythology. He was "the greatest hero and slayer of monsters, alongside Cadmus and Perseus, before the days of Heracles",[3] and his greatest feat was killing the Chimera, a monster that Homer depicted with a lion's head, a goat's body, and a serpent's tail: "her breath came out in terrible blasts of burning flame."[4]

| Bellerophon | |

|---|---|

Slayer of the Chimera | |

| Member of the Corinthian Royal Family | |

| |

| Other names | Hipponous |

| Predecessor | Iobates |

| Successor | ?Hippolochus |

| Abode | Potniae, later Argos and Lycia |

| Personal information | |

| Parents | (1) Poseidon and Eurynome (2) Glaucus and Eurymede |

| Siblings | (2) Deliades |

| Consort | (1) Philonoe (2) Asteria |

| Offspring | (1) Isander, Hippolochus and Laodamia (2) Hydissos |

| Greek mythology |

|---|

|

| Deities |

|

| Heroes and heroism |

|

| Related |

|

|

|

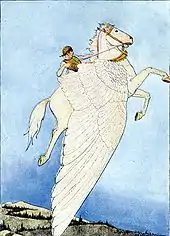

Bellerophon was also known for capturing the winged horse Pegasus with the help of Athena’s charmed bridle, and earning the disfavour of the gods after attempting to ride Pegasus to Mount Olympus to join them.[5]

Etymology

One possible etymology that has been suggested is: Βελλεροφόντης (Bellerophóntēs) from Ancient Greek βέλεμνον (bélemnon), βελόνη (belóne), βέλος (bélos, "projectile, dart, javelin, needle, arrow") and -φόντης (-phóntēs, "slayer") from φονεύω (phoneúō, "to slay").[lower-alpha 2] However, Geoffrey Kirk says that "Βελλεροφόντης means 'slayer of Belleros'".[8] He must have been named so after slaying an original enemy named Belleros, but there is no trace left of this ancient foe; nevertheless it must have been there from the beginning in order for Bellerophon to gain his universally-accepted name, much like Hermes got his 'Argeiphontes' epithet after slaying Argus Panoptes.[9] Belleros could have been a Lycian, a local daimon or a Corinthian nobleman—Bellerophon's name "clearly invited all sorts of speculation".[8][lower-alpha 3]

Family

Bellerophon was the son of the mortal Eurynome (Eurymede[11]) by either her husband, Glaucus, or Poseidon. He was the brother of Deliades (also named Peiren or Alcimenes).[12]

Bellerophon was the father of Isander[13] (Peisander),[14] Hippolochus,[15] and Laodamia[16] (Deidamia[17] or Hippodamia[18]) by Philonoe, daughter of King Iobates of Lycia. Philonoe was also known under several other names: Alkimedousa,[19] Anticleia,[20] Pasandra or Cassandra.[21] In some accounts, Bellerophon also fathered Hydissos by Asteria, daughter of Hydeus.[22]

Mythology

The Iliad vi.155–203 contained an embedded narrative told by Bellerophon's grandson Glaucus (who was named after his great-grandfather), which recounted Bellerophon's myth. Bellerophon's father was Glaucus,[23] who was the King of Potniae and son of Sisyphus. Bellerophon's grandsons Sarpedon and the younger Glaucus fought in the Trojan War. In Stephanus of Byzantium’s Ethnica, a genealogy was given for Chrysaor ("of the golden sword") that would make him a double of Bellerophon; he was called the son of Glaucus (son of Sisyphus). Chrysaor has no myth save that of his birth: from the severed neck of Medusa, who was with child by Poseidon, he and Pegasus both sprang at the moment of her death. "From this moment we hear no more of Chrysaor, the rest of the tale concerning the stallion only... [who visited the spring of Pirene] perhaps also for his brother's sake, by whom in the end he let himself be caught, the immortal horse by his mortal brother."[24]

Exile in Argos

Bellerophon's brave journey began in the familiar way,[25] with an exile: he had murdered either his brother, whose name was usually given as Deliades, Peiren or even Alcimenes, or killed a shadowy "enemy", a "Belleros"[26] or "Belleron", a ruler of the Corinthians (though the details are never directly told), and in expiation of his crime arrived as a suppliant to Proetus, king in Tiryns, one of the Mycenaean strongholds of the Argolid. Proetus, by virtue of his kingship, cleansed Bellerophon of his crime. The wife of the king, whether named Anteia[27] or Stheneboea,[28] took a fancy to him, but when he rejected her, she accused Bellerophon of attempting to ravish her.[29] Proetus dared not satisfy his anger by killing a guest (who is protected by xenia), so he sent Bellerophon to King Iobates his father-in-law, in the plain of the River Xanthus in Lycia, bearing a sealed message in a folded tablet, a letter which read: "Pray remove the bearer from this world: he attempted to violate my wife, your daughter."[30] Before opening the tablets, Iobates feasted with Bellerophon for nine days. On reading the tablet's message Iobates too feared the wrath of the Erinyes if he murdered a guest; so he sent Bellerophon on a mission that he deemed impossible: to kill the Chimera, living in neighboring Caria. The Chimera was a fire-breathing monster consisting of the body of a goat, the head of a lion and the tail of a serpent. This monster had terrorized the nearby countryside. On his way he encountered the famous Corinthian seer Polyeidos, who gave him advice about his oncoming battle.

Capturing Pegasus

_-_13.JPG.webp)

Polyeidos told Bellerophon that he would have need of Pegasus. To obtain the services of the untamed winged horse, Polyeidos told Bellerophon to sleep in the temple of Athena. While Bellerophon slept, he dreamed that Athena set a golden bridle beside him, saying "Sleepest thou, prince of the house of Aiolos? Come, take this charm for the steed and show it to the Tamer thy father as thou makest sacrifice to him of a white bull."[31] It was there when he awoke. Bellerophon had to approach Pegasus while it drank from a well; Polyeidos told him which well —the never-failing Pirene on the citadel of Corinth, the city of Bellerophon's birth. Other accounts say that Athena brought Pegasus already tamed and bridled, or that Poseidon the horse-tamer, secretly the father of Bellerophon, brought Pegasus, as Pausanias understood.[32] Bellerophon mounted his steed and flew off to where the Chimera was said to dwell.

The Slaying of the Chimera

When Bellerophon arrived in Lycia to face the ferocious Chimera, he could not harm the monster even while riding Pegasus. He felt the Chimera's hot breath and was struck with an idea. He got a large block of lead and mounted it on his spear. He then flew head-on towards the Chimera, holding out the spear as far as he could. Before breaking off his attack, he lodged the block of lead inside the Chimera's throat. The beast's fire-breath melted the lead, which blocked its air passage, suffocating it.[33] Bellerophon returned victorious to King Iobates.[34] On Bellerophon's return, however, the king was unwilling to believe his story. A series of daunting quests ensued: Bellerophon was sent against the warlike Solymi and then against the Amazons, who fought like men, whom Bellerophon vanquished by dropping boulders from his winged horse. When he was sent against a Carian pirate, Cheirmarrhus, an ambush failed when Bellerophon killed everyone sent to assassinate him. The palace guards then were sent against him, but Bellerophon called upon Poseidon, who flooded the plain of Xanthus behind Bellerophon as he approached. To defend themselves, the palace women rushed from the gates with their robes lifted high to expose themselves. Unwilling to confront them while they were undressed, Bellerophon withdrew.[35] Iobates relented, produced the letter, and allowed Bellerophon to marry his daughter Philonoe, the younger sister of Anteia, and shared with him half his kingdom,[36] with its fine vineyards and grain fields. The lady Philonoe bore him Isander (Peisander),[14][37] Hippolochus and Laodamia, who lay with Zeus the Counselor and bore Sarpedon, but was slain by Artemis.[38][39][40]

Flight to Olympus and fall

As Bellerophon's fame grew, so did his arrogance. Bellerophon felt that because of his victory over the Chimera, he deserved to fly to Mount Olympus, the home of the gods. That act of hubris angered Zeus and he sent a gadfly to sting Pegasus, causing Bellerophon to fall back to Earth. Pegasus completed the flight to Olympus where Zeus used him as a pack horse for his thunderbolts.[41] On the Plain of Aleion ("Wandering") in Cilicia, Bellerophon, who had been blinded after falling into a thorn bush, lived out his life in misery, "devouring his own soul", until he died.[42][43]

Euripides' Bellerophon

Enough fragments of Euripides' lost tragedy, Bellerophon, remain as about thirty quotations in surviving texts, giving scholars a basis for assessing its theme: the tragic outcome of his attempt to storm Olympus on Pegasus. An outspoken passage—in which Bellerophon seems to doubt the gods' existence, due to the contrast between the wicked and impious, who live lives of ease, with the suffering of the good—is apparently the basis for Aristophanes' imputation of "atheism" to the poet.[44]

Perseus on Pegasus

The replacement of Bellerophon by the more familiar culture hero Perseus was a development of Classical times that was standardized during the Middle Ages and has been adopted by the European poets of the Renaissance and later.[45]

Footnotes

- An alternate name for Bellerophon was Hipponous.[1]

- The nomen agentis is also attested in the compound Ἀργειφόντης Argeïphontes, an epithet of god Hermes that means 'Slayer of [the Giant] Argos'.[6][7]

- It is also understood that Belleros is "a character whose further mentions don't exist in the extant literature".[10]

References

- Assunçâo, Teodoro Renno. "[www.persee.fr/doc/gaia_1287-3349_1997_num_1_1_1332 Le mythe iliadique de Bellérophon]". In: Gaia: revue interdisciplinaire sur la Grèce Archaïque, numéro 1-2, 1997. pp. 42-43. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/gaia.1997.1332

- Tzetzes, Chiliades 7.810 (TE2.149); Scholia on Pindar, Olympian Ode 13.66

- Kerenyi 1959, p. 75.

- Iliad vi.155–203.

- Roman, Luke; Roman, Monica (2010). Encyclopedia of Greek and Roman Mythology. Infobase Publishing. p. 103. ISBN 978-1-4381-2639-5.

- Breuil, Jean-Luc. "ΚΡΑΤΟΣ et sa famille chez Homère: étude sémantique". In: Études homériques. Séminaire de recherche sous la direction de Michel Casevitz. Lyon: Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux, 1989. p. 41. (Travaux de la Maison de l'Orient, 17) www.persee.fr/doc/mom_0766-0510_1989_sem_17_1_1734

- Sauge, André. "[www.persee.fr/doc/gaia_1287-3349_2005_num_9_1_1476 Remarques sur quelques aspects linguistiques de l'épopée homérique et sur leurs conséquences pour l'époque de fixation du texte (Seconde Partie)]". In: Gaia: revue interdisciplinaire sur la Grèce Archaïque, numéro 9, 2005. p. 117. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/gaia.2005.1476

- Kirk 1990, p. 178

- Kerenyi 1959, p. 79

- "... 'tueur de Belléros', personnage dont aucune autre mention n'apparaît dans la littérature conservée". Tourraix, Alexandre. Le mirage grec. L'Orient du mythe et de l'épopée. Besançon: Institut des Sciences et Techniques de l'Antiquité, 2000. p. 116. (Collection « ISTA », 756) DOI: https://doi.org/10.3406/ista.2000.2506; www.persee.fr/doc/ista_0000-0000_2000_mon_756_1

- Apollodorus, 1.9.3

- Apollodorus, 1.9.3 & 2.3.1

- Homer, Iliad 6.196–197; Apollodorus, 2.3.1

- Strabo, Geographica 12.8.5 & 13.4.16

- Homer, Iliad 6.206–210

- Homer, Iliad 6.197–205

- Diodorus Siculus, 5.79.3

- Pseudo-Clement, Recognitions 10.21

- Scholia on Homer, Iliad 6.192

- Scholia on Pindar, Olympian Ode 13.61

- Scholia on Homer, Iliad 6.155

- Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Hydissos

- By some accounts, Bellerophon's father was really Poseidon. Kerenyi 1959 p. 78 suggests that "sea-green" Glaucus is a double for Poseidon, god of the sea, who looms behind many of the elements in Bellerophon's myth, not least as the sire of Pegasus and of Chrysaor, but also as the protector of Bellerophon.

- Kerenyi 1959 p. 80.

- See Joseph Campbell, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, chapter 1, "Separation".

- The suggestion, made by Kerenyi and others, makes the name "Bellerophontes" the "killer of Belleros", just as Hermes Argeiphontes is "Hermes the killer of Argus". Carpenter, Rhys (1950). "Argeiphontes: A Suggestion". American Journal of Archaeology. 54 (3): 177–183. doi:10.2307/500295. JSTOR 500295. S2CID 191378610., makes a carefully argued case for Bellerophontes as the "bane-slayer" of the "bane to mankind" in Iliad II.329, derived from a rare Greek word έλλερον, explained by the grammarians as κακόν, "evil". This έλλερον is connected by Katz, J. (1998). "How to be a Dragon in Indo-European: Hittite illuyankas and its Linguistic and Cultural Congeners in Latin, Greek, and Germanic". In Jasanoff; Melchert; Oliver (eds.). Mír Curad. Studies in Honor of Calvert Watkins. Innsbruck. pp. 317–334. ISBN 3851246675. with a Hesychius gloss ελυες "water animal", and an Indo-European word for "snake", or "dragon", cognate to English eel, also found in Hittite Illuyanka, which would make Bellerophon the dragon slayer of Indo-European myth, represented by Indra slaying Vrtra in Indo-Aryan, and by Thor slaying the Midgard Serpent in Germanic. Robert Graves in The Greek Myths rev. ed. 1960 suggested a translation "bearing darts".

- In Iliad vi.

- Euripides' tragedies Stheneboia and Bellerophontes are lost.

- This mytheme is most familiar in the narrative of Joseph and Potiphar's wife. Robert Graves also notes the parallel in the Egyptian Tale of Two Brothers and in the desire of Athamas' wife for Phrixus (Graves 1960, 70.2, 75.1).

- The tablets "on which he had traced a number of devices with a deadly meaning" constitute the only apparent reference to writing in the Iliad. Such a letter is termed a "bellerophontic" letter; one such figures in a subplot of Shakespeare's Hamlet, bringing offstage death to Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. Such a letter figures in the earlier story of Sargon of Akkad.

- Kerenyi 1959, quoting Apollodorus Mythographus, 2.7.4.

- Description of Greece 2.4.6.

- Some red-figure pottery painters show Bellerophon wielding Poseidon's trident instead (Kerenyi 1959).

- Hesiod, Theogony 319ff; Bibliotheke, ii.3.2; Pindar, Olympian Odes, xiii.63ff; Pausanias, ii.4.1; Hyginus, Fabulae, 157; John Tzetzes, On Lycophron.

- Robert Graves, 75.d; Plutarch, On the Virtues of Women.

- The inheritance of kingship through the king's daughter, with many heroic instances, was discussed by Finkelberg, Margalit (1991). "Royal succession in heroic Greece". The Classical Quarterly. New Series. 41 (2): 303–316. doi:10.1017/s0009838800004481. JSTOR 638900. S2CID 170683301.; compare Orion and Merope.

- Isander was struck down by Ares in battle with the Solymi (Iliad xvi).

- Homer, Iliad, 6. 197–205

- Oxford Classical Mythology Online. "Chapter 25: Myths of Local Heroes and Heroines". Classical Mythology, Seventh Edition. Oxford University Press USA. Archived from the original on July 15, 2011. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- In Diodorus Siculus's Bibliotheca historica 5.79.3: she was referred as Deidamia and made her wife of Evander, son of Sarpedon the elder, and by her, father of Sarpedon the younger.

- Parallels are in the myths of Icarus and Phaeton.

- Homer (1924). The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Vol. I (book 6, lines 202-204). Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- Pindar, Olympian Odes, xiii.87–90, and Isthmian Odes, vii.44; Bibliotheke ii.3.2; Homer, Iliad vi.155–203 and xvi.328; Ovid, Metamorphoses ix.646.

- Riedweg, Christoph (1990). "The 'atheistic' fragment from Euripides' Bellerophontes (286 N²)". Illinois Classical Studies. 15 (1): 39–53. ISSN 0363-1923.

- Johnston, George Burke (1955). "Jonson's 'Perseus upon Pegasus'". The Review of English Studies. New Series. 6 (21): 65–67. doi:10.1093/res/VI.21.65.

Further reading

- Graves, Robert, 1960. The Greek Myths, revised edition (Harmondsworth: Penguin)

- Homer, Iliad, book vi.155–203

- Kerenyi, Karl, 1959. The Heroes of the Greeks (London: Thames and Hudson)

- Kirk, G. S., 1990. The Iliad: A Commentary Volume II: books 5-8. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press)

External links

- Images of Bellerophon in the Warburg Institute Iconographic Database

.jpg.webp)