Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim

Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (Swedish pronunciation: [kɑːɭ ˈɡɵ̂sːtav ˈěːmɪl ˈmânːɛrˌhɛjm], Finland Swedish: [kɑːrl ˈɡʉstɑv ˈeːmil ˈmɑnːærˌhejm] (![]() listen); 4 June 1867 – 27 January 1951) was a Finnish military leader and statesman.[3][4] He served as the military leader of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, as Regent of Finland (1918–1919), as commander-in-chief of Finland's defence forces during the period of World War II (1939–1945), as Marshal of Finland (1942–), and as the sixth president of Finland (1944–1946).

listen); 4 June 1867 – 27 January 1951) was a Finnish military leader and statesman.[3][4] He served as the military leader of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, as Regent of Finland (1918–1919), as commander-in-chief of Finland's defence forces during the period of World War II (1939–1945), as Marshal of Finland (1942–), and as the sixth president of Finland (1944–1946).

The Honourable Marshal of Finland Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim VR SR, SVR SR ketj., SL SR | |

|---|---|

Mannerheim in 1940 | |

| 6th President of Finland | |

| In office 4 August 1944 – 11 March 1946 | |

| Prime Minister |

|

| Preceded by | Risto Ryti |

| Succeeded by | Juho Kusti Paasikivi |

| Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Defence Forces | |

| In office 30 November 1939 – 12 January 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Hugo Österman (as Commander of the Hosts) |

| Succeeded by | Axel Heinrichs (as Chief of Defence) |

| In office 25 January 1918 – 30 May 1918 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Karl Fredrik Wilkama |

| State Regent of Finland | |

| In office 12 December 1918 – 26 July 1919 | |

| Preceded by | Pehr Evind Svinhufvud |

| Succeeded by | Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg (as President of the Republic) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 4 June 1867[1] Louhisaari Manor, Askainen, Grand Duchy of Finland, Russian Empire[1] |

| Died | 27 January 1951 (aged 83) Cantonal Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland |

| Resting place | Hietaniemi Cemetery, Helsinki, Finland |

| Spouse | Anastasie Arapova (div. 1919) |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Profession | Military officer, statesman |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch/service |

|

| Years of service |

|

| Rank |

|

| Battles/wars | |

The Russian Empire dominated the Grand Duchy of Finland before 1917, and Mannerheim made a career in the Imperial Russian Army, rising by 1917 to the rank of lieutenant general. He had a prominent place in the ceremonies for Emperor Nicholas II's coronation in 1896 and later had several private meetings with the Tsar. After the Bolshevik revolution of November 1917 in Russia, Finland declared its independence (6 December 1917) – but soon became embroiled in the 1918 Finnish Civil War between the pro-Bolshevik "Reds" and the "Whites", who were the troops of the Senate of Finland, supported by troops of the German Empire. A Finnish delegation appointed Mannerheim as the military chief of the Whites in January 1918. Mannerheim was appointed as Commander-in-Chief of the country's armed forces in November 1939 after the Soviet invasion of Finland. He personally participated in the planning of Operation Barbarossa[5] and led the Finnish Defence Forces in an invasion of the USSR alongside Nazi Germany known as the Continuation War (1941–1944). In 1944, when the prospect of Nazi Germany's defeat in World War II became clear, the Finnish Parliament appointed Mannerheim as President of Finland, and he oversaw peace-negotiations with the Soviet Union and the UK. He resigned from the presidency in 1946 and died in 1951.

Participants in a Finnish survey taken 53 years after his death voted Mannerheim the greatest Finn of all time.[6] During his own lifetime he became, alongside Jean Sibelius, the best-known Finnish personage at home and abroad.[4] Given the broad recognition in Finland and elsewhere of his unparalleled role in establishing and later preserving Finland's independence from the Soviet Union, Mannerheim has long been referred to as the father of modern Finland,[7][8][9][10][11] and the New York Times has called the Finnish capital Helsinki's Mannerheim Museum memorializing the leader's life and times "the closest thing there is to a [Finnish] national shrine".[9] On the other hand, Mannerheim's personal reputation still strongly divides opinions among people even to this day, with critics highlighting his role as General of the White Guard in the fate of the Red Prisoners during and after the Finnish Civil War.[12] Mannerheim is the only Finn to have held the rank of field marshal, an honorary rank bestowed upon especially distinguished generals.[13]

Early life and military career

Ancestry

The Mannerheims, originally from Germany as Marhein, became Swedish noblemen in 1693. In the latter part of the 18th century, they moved to Finland, which was then an integral part of Sweden.[14][15] After Sweden lost Finland to the Russian Empire in 1809, Mannerheim's great-grandfather, Count Carl Erik Mannerheim (1759–1837), son of the Commandant Johan Augustin Mannerheim,[16][17] became the first head of the executive of the newly-autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland, an office that preceded that of the contemporary Prime Minister. His grandfather, Count Carl Gustaf Mannerheim (1797–1854), was an entomologist and jurist. His father, Carl Robert, Count Mannerheim (1835–1914), was both a playwright and industrialist, with modest success in both endeavours. Mannerheim's mother, Hedvig Charlotta Helena von Julin (1842–1881), was the daughter of a wealthy industrialist, John von Julin (1787–1853).

Childhood

Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim was born in the Louhisaari Manor of the Askainen parish (current Masku) on June 4, 1867.[1] After Mannerheim's father left the family for his mistress in 1880,[18] his mother and her seven children went to live with her aunt Louise, but she died the following year.[19] Mannerheim's maternal uncle, Albert von Julin (1846–1906), then became his legal guardian and financier of his later schooling.[20] The third child of the family, Mannerheim inherited the title of Baron.

Education

Mannerheim was sent to the Hamina Cadet School, a state school educating aristocrats for the Imperial Russian Army, in 1882.[21] The handsome young Baron towered over his classmates, standing 6 ft 4 in (1.93 m). He was expelled in 1886 when he left without permission.[22] Next he attended the Helsinki Private Lyceum, where he passed the university entrance examinations in June 1887.[23] From 1887 to 1889, Mannerheim attended the Nicholas Cavalry College in St. Petersburg.[24] In January 1891, he joined the Chevalier Guard Regiment in St Petersburg.[25]

In 1892, he married a wealthy noble of Russian-Serbian heritage, Anastasia Arapova (1872–1936).[26][27] They had two daughters, Anastasie "Stasie" (1893–1978) and Sofia "Sophy" (1895–1963).[28] The couple separated in 1902 and divorced in 1919.[29] Mannerheim served in the Imperial Chevalier Guard until 1904. In 1896, he took part in the coronation of Emperor Nicholas II, standing for four hours in his full-dress Imperial Chevalier Guard uniform at bottom of the steps leading up to the imperial throne.[30] Mannerheim always considered the coronation a high-point of his life, recalling with pride his role in what he called an "indescribably magnificent" coronation.[30] An expert rider, one of his duties was buying horses for the army. In 1903, he was put in charge of the model squadron in the Imperial Chevalier Guard and became a member of the equestrian training board of the cavalry regiments.[31]

Language skills

Mannerheim's mother tongue was Swedish. He spoke fluent German, French, and Russian, the latter of which he learned in the forces of the Russian Imperial Army. He also spoke some English, Polish, Portuguese, Latin, and Chinese.[32] He didn't start learning Finnish properly until after Finland's independence.[33]

Service in the Imperial Russian Army

Mannerheim volunteered for active service with the Imperial Russian Army in the Russo-Japanese War in 1904. He was transferred to the 52nd Nezhin Dragoon Regiment in Manchuria, with the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. During a reconnaissance patrol on the plains of Manchuria, he first saw action in a skirmish and had his horse shot out from under him.[30] He was promoted to Colonel for bravery in the Battle of Mukden in 1905[34] and briefly commanded an irregular unit of Hong Huzi, a local militia, on an exploratory mission into Inner Mongolia.[35] During the war, Mannerheim also managed to lead a group of local thugs and crooks with whom he sought the back of the enemy to defeat them.[36]

Mannerheim, who had a long career in the Imperial Russian army, also rose to become a courtier of Emperor of all the Russias Nicholas II, even holding a place of honour at his coronation.[36] When Mannerheim returned to St. Petersburg, he was asked to undertake a journey through Turkestan to Beijing as a secret intelligence officer. The Russian General Staff wanted accurate, on-the-ground intelligence about the reforms and activities by the Qing dynasty, as well as the military feasibility of invading Western China: a possible move in their struggle with Britain for control of inner Asia.[37][38] Disguised as an ethnographic collector, he joined the French archeologist Paul Pelliot's expedition at Samarkand in Russian Turkestan (now Uzbekistan). They started from the terminus of the Trans-Caspian Railway in Andijan in July 1906, but Mannerheim quarreled with Pelliot,[37] so he made the greater part of the expedition on his own.[39]

With a small caravan, including a Cossack guide, Chinese interpreter, and Uyghur cook, Mannerheim first trekked to Khotan in search of British and Japanese spies. After returning to Kashgar, he headed north into the Tian Shan range, surveying passes and gauging the stances of the tribes towards the Han Chinese. Mannerheim arrived in the provincial capital of Urumqi, and then headed east into Gansu province. At the sacred Buddhist mountain of Mount Wutai in Shanxi province, Mannerheim met the 13th Dalai Lama of Tibet. He showed the Dalai Lama how to use a pistol.[41]

He followed the Great Wall of China, and investigated a mysterious tribe known as Yugurs.[42] From Lanzhou, the provincial capital, Mannerheim headed south into Tibetan territory and visited the lamasery of Labrang, where he was stoned by xenophobic monks.[43] During his trip to Tibet in 1908 Mannerheim became the third European who had met with Dalai lama.[44] Mannerheim arrived in Beijing in July 1908, returning to St. Petersburg via Japan and the Trans-Siberian Express. His report gave a detailed account of Chinese modernization, covering education, military reforms, colonization of ethnic borderlands, mining and industry, railway construction, the influence of Japan, and opium smoking.[43] He also discussed the possibility of a Russian invasion of Xinjiang, and Xinjiang's possible role as a bargaining chip in a putative future war with China.[45] His trip through Asia left him with a lifelong love of Asian art, which he thereafter collected.[41]

After returning to Russia in 1909 from the expedition, Mannerheim presented to his emperor its results of which Nicholas II listened with interest and of which there were many artifacts that are still on display in the museum.[36] After that, Mannerheim was appointed to command the 13th Vladimir Uhlan Regiment in the Congress Kingdom of Poland. The following year, he was promoted to major general and was posted as the commander of the Life Guard Uhlan Regiment of His Imperial Majesty in Warsaw. Next Mannerheim became part of the Imperial entourage and was appointed to command a cavalry brigade.[46]

At the beginning of World War I, Mannerheim served as commander of the Guards Cavalry Brigade, and fought on the Austro-Hungarian and Romanian fronts. In December 1914, after distinguishing himself in combat against the Austro-Hungarian forces, Mannerheim was awarded the Order of St. George, 4th class. In March 1915, Mannerheim was appointed to command the 12th Cavalry Division.[47]

Mannerheim received leave to visit Finland and St. Petersburg in early 1917 and witnessed the outbreak of the February Revolution. After returning to the front, he was promoted to lieutenant general in April 1917 (the promotion was backdated to February 1915), and took command of the 6th Cavalry Corps in the summer of 1917. However, Mannerheim fell out of favour with the new government, who regarded him as not supporting the revolution, and was relieved of his duties. He decided to retire and returned to Finland.[46] Mannerheim kept a large portrait of Emperor Nicholas II in the living room of his house in Helsinki right up to his death, and when asked after the overthrow of the House of Romanov why he kept the portrait up, he always answered: "He was my emperor".[41]

Political career

The White General and the Regent of Finland

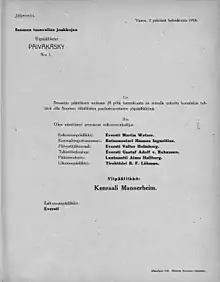

In December 1917, Finland declared independence from the newly communist Russia, which the Soviet government immediately recognized as legitimate, with respect to their November declaration affirming the right of their subjects' self-determination, including secession (albeit with the assumption that such declarations would be followed by communist revolutions anyway). The Finnish parliament appointed P. E. Svinhufvud to lead the newly independent grand duchy's interregnum government. In January 1918, a military committee was charged with bolstering the Finnish army, then not much more than some locally organised White Guards. Mannerheim was appointed to the committee, but soon resigned to protest its indecision. On 13 January he was given command of the army.[48] He had only 24,000 newly enlisted, mostly untrained men. The Finnish Red Guard, led by communist leader Kullervo Manner, had 30,000 men and there were 70,000 Russian troops in Finland. His army was financed by a fifteen million mark line of credit provided by the bankers. His raw recruits had few arms. Nonetheless, he marched them to Vaasa, which was garrisoned by 42,500 Russians.[49] He surrounded the Russian garrison with a mass of men; the defenders could not see that only the front rank was armed, so they surrendered, providing badly needed arms. Further weapons were purchased from Germany. Eighty-four Swedish officers and 200 Swedish NCOs served in the Finnish Civil War (or War of Liberty, as it was known among the "Whites"). Other officers were Finns who had been trained by the Germans as a Jäger Battalion. In March 1918 they were aided by German troops landing in Finland and occupying Helsinki.

After the Whites' victory in the bitterly fought civil war, during which both sides employed ruthless terror tactics, Mannerheim resigned as commander-in-chief. He left Finland in June 1918 to visit relatives in Sweden.[50]

In Stockholm, Mannerheim conferred with Allied diplomats, emphasizing his opposition to the Finnish government's policy: they were confident that the Germans would win the war, and had declared the Kaiser's brother-in-law, Frederick Charles of Hesse, to be the King of Finland. In the meantime Svinhufvud served as the first Regent of the nascent kingdom. Mannerheim's rapport with the Allies was recognized in October 1918 when the Finnish government sent him to Britain and France to attempt to gain Britain's and the United States's recognition of Finland's independence. In December, he was summoned back to Finland; Frederick Charles had renounced the throne, and in his stead, Mannerheim had been elected Regent. As Regent, Mannerheim often signed official documents using Kustaa, the Finnish form of his Christian name, to emphasize his Finnishness to those who were suspicious of his background in the Russian armed forces and his difficulties with the Finnish language.[32] Mannerheim disliked his last Christian name, Emil, and wrote his signature as C.G. Mannerheim, or simply Mannerheim. Among his relatives and close friends Mannerheim was called Gustaf.[51]

Mannerheim secured recognition of Finnish independence from Britain and the United States. In July 1919, after he had confirmed a new, republican constitution, Mannerheim stood as a candidate in the first presidential election, with parliament as the electors. He was supported by the National Coalition Party and the Swedish People's Party. He finished second to Kaarlo Juho Ståhlberg, and withdrew from public life.[46]

Interwar period

In the interwar years, Mannerheim held no public office. This was largely due to his being seen by many politicians of the centre and left as a controversial figure for his ruthless battle with the Bolsheviks, his supposed desire for Finnish intervention on the side of the Whites during the Russian Civil War, and the Finnish socialists' antipathy toward him. They saw him as the bourgeois "White General". Mannerheim doubted that modern party-based politics would produce principled and high-quality leaders in Finland or elsewhere. In his gloomy opinion, the fatherland's interests were too often sacrificed by the democratic politicians for partisan benefit.[53][54] While serving as a regent, Mannerheim had desired more power because, as an aristocrat, he was afraid of the democracy that had come to power in Finland.[36] Supporting him was the conspiracy of the far right-wing, in the background of which Elmo Kaila, among others, was a grey eminence. Still, the project to raise the white chief to the "Dictator of Finland" went nowhere.[36] The attack on Petrograd, which Mannerheim fervently incubated, did not materialize either.[36] Thus, Mannerheim disappeared from Finnish politics for almost a decade.

He kept busy heading the Finnish Red Cross (Chairman 1919–1951), was a member of the board of the International Red Cross, and founded the Mannerheim League for Child Welfare (Mannerheimin Lastensuojeluliitto). He was also the chairman of the supervisory board of a commercial bank, the Liittopankki-Unionsbanken, and after its merger with the Bank of Helsinki, the chairman of the supervisory board of that bank until 1934, and was a member of the board of Nokia Corporation.[55]

In the 1920s and 1930s, Mannerheim returned to Asia, where he travelled and hunted extensively.[56] On his first trip in 1927, to avoid going through the Soviet Union, he travelled through the British Empire, going by ship from London to Bombay. From there he travelled to Lucknow, Delhi and Calcutta in the British India. From there he travelled overland to Burma, where he spent a month at Rangoon and Mandalay. He then went on to Sikkim and returned to Finland by car and aeroplane.[55]

In his second voyage, in 1936, he went by ship from Aden (a British territory in Southern Arabia) to Bombay. During his travels and hunting expeditions, he visited Madras, Delhi and Nepal, where he was invited by the Rana Prime Minister Tin Maharaja Sir Joodha Shumser Jung Bahadur Rana to join a tiger hunt.[57] In the same year, Mannerheim made a private visit to the United Kingdom, where he was accompanied for the first time by security guards, who Prime Minister Winston Churchill himself had given Mannerheim to use during the trip. However, Mannerheim is known to have been bothered by the presence of security guards, because mainly as a fatalist, he firmly believed in fate, if it had to happen in the form of an untimely death, and in addition, he also strongly trusted his own authority.[58]

In 1929, Mannerheim refused the right-wing radicals' plea to become a de facto military dictator, although he did express some support for the right-wing Lapua Movement.[59] After President Pehr Evind Svinhufvud was elected in 1931, he appointed Mannerheim as chairman of Finland's Defence Council and gave him a written promise that in the event of war he would become the Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Army. (Svinhufvud's successor Kyösti Kallio renewed this promise in 1937). In 1933, Mannerheim received the rank of Field Marshal (sotamarsalkka, fältmarskalk). By this time, Mannerheim had come to be seen by the public, including some former socialists, less as a "White General" and more as a nonpartisan figure, enhanced by his public statements urging reconciliation between the opposing sides in the Civil War and the need to focus on national unity and defence: "we need not ask where a man stood fifteen years ago".[60] Mannerheim supported Finland's military industry and sought in vain to obtain a military defence union with Sweden. However, rearming the Finnish army did not occur as swiftly or as well as he hoped, and he was not enthusiastic about a war. He had many disagreements with various Cabinets, and signed many letters of resignation.[61][62]

The 1920 assassination attempt

After the end of the Civil War, the defeat experienced by the Reds was so bitter that Mannerheim became a target of assassination. One of the would-be assassins was Eino Rahja,[63] who was in charge of the St. Petersburg International School of Red Officers, who began planning an assassination project by assembling eight groups of Finnish Red Guards in St. Petersburg for this purpose. The attack was to be implemented in April 1920 during a White Guard's parade on the Hämeenkatu in Tampere, in which General Mannerheim participated.[58]

The men of the group gathered on April 3 at the Park Café in Hämeenkatu and at this stage Karl Salo, who belonged to the group, was assigned as a shooter and gave him a Colt pistol. However, the assassination attempt failed due to Salo's hesitation,[58] and during the crowd, Salo's securities Aleksander Weckman and Aleksanteri Suokas, equipped with Walther and Colt pistols, lost sight of him and never had time to shoot Mannerheim.[64]

On April 6, Weckman, who led the operation, got hold of Salo and gave him a week to kill either Mannerheim or the Minister of War and Uusimaa County Governor, Bruno Jalander,[65] otherwise he would die himself. This attempt was also unsuccessful, as Mannerheim and Jalander did not come to the Helsinki Conservation Party celebration after the authorities received a tip. Salo returned his pistol and escaped afterwards. Weckman and Suokas tried to escape to the Soviet Union with their two assistants but were arrested from the Helsinki-Vyborg train on the night of April 21. Salo was arrested in Espoo on April 23.[64]

Commander-in-Chief

When negotiations with the Soviet Union failed in 1939, and aware of the imminent war and deploring the lack of equipment and preparation of the army, Mannerheim resigned once again from the military council on 17 October 1939, declaring that he would only agree to return to business as Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Army. He officially became the supreme commander of the armies, at the age of 72, after the Soviet attack, the November 30, 1939. In a letter to his daughter Sophie, he stated, "I had not wanted to undertake the responsibility of commander-in-chief, as my age and my health entitled me, but I had to yield to appeals from the President of the Republic and the government, and now for the fourth time I am at war."[32]

He addressed the first of his often controversial orders of the day to the Defence Forces on the day the war began:

The President of the Republic has appointed me on 30 November 1939 as Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces of the country. Brave soldiers of Finland! I enter on this task at a time when our hereditary enemy is once again attacking our country. Confidence in one's commander is the first condition for success. You know me and I know you and know that everyone in the ranks is ready to do his duty even to death. This war is nothing other than the continuation and final act of our War of Independence. We are fighting for our homes, our faith, and our country.[32]

The defensive field fortifications they manned became known as the Mannerheim Line.

Field Marshal Mannerheim quickly organised his headquarters in Mikkeli. His chief of staff was Lieutenant General Aksel Airo, while his close friend, General Rudolf Walden, was sent as a representative of the headquarters to the cabinet from 3 December 1939 until 27 March 1940, after which he became defence minister.[61][62]

Mannerheim spent most of the Winter War and Continuation War in his Mikkeli headquarters but made many visits to the front. Between the wars, he remained commander-in-chief.[62] Although Mannerheim's main task was to lead the war, he also knew how to strengthen and maintain the will of the soldiers to fight. He was famed for this quote:

"Forts, cannons and foreign aid will not help unless every man himself knows that he is the guard of his country."[66]

Mannerheim kept relations with Adolf Hitler's government as formal as possible. Mannerheim did not really appreciate Hitler,[67] even though he initially expressed an interest in his rise to power; his mind changed at the point when Mannerheim's visit to Germany made him realize what kind of "ideal state" Hitler was building.[68] Before the Continuation War, the Germans offered Mannerheim command over 80,000 German troops in Finland. Mannerheim declined so as to not tie himself and Finland to Nazi war aims;[69] Mannerheim was ready for cooperation and fraternity with Hitler's Germany, but for practical rather than ideological reasons because of the Soviet threat.[68] In July 1941 the Finnish Army of Karelia was strengthened by the German 163rd Infantry Division. They retook the Finnish territories annexed by the Soviet Union after the Winter War,[70] and went further, occupying East Karelia. Finnish troops took part in the Siege of Leningrad, which lasted 872 days.

Visit by Adolf Hitler

Mannerheim's 75th birthday, 4 June 1942, was a national celebration. The government granted him the unique title of Marshal of Finland (Suomen Marsalkka in Finnish, Marskalk av Finland in Swedish). So far he is the only person to receive the title. A surprise birthday visit by Hitler occurred on the day as he wished to visit the "brave Finns (die tapferen Finnen)" and their leader Mannerheim.[61][62] Mannerheim did not want to meet him at his headquarters or in Helsinki, as then it would seem like an official state visit. The meeting took place near Imatra, in south-eastern Finland, and was arranged in secrecy.[61] From Immola Airfield, Hitler, accompanied by President Ryti, was driven to where Baron Mannerheim was waiting at a railway siding. A speech from Hitler was followed by a birthday meal and negotiations between him and Mannerheim. Overall, Hitler spent about five hours in Finland; he reportedly asked the Finns to step up military operations against the Soviets, but apparently made no specific demands.[61]

During the visit, an engineer of the Finnish broadcasting company Yleisradio, Thor Damen, succeeded in recording the first eleven minutes of Hitler's and Mannerheim's private conversation. This had to be done secretly, as Hitler never allowed off-guard recordings. Damen was assigned to record the official birthday speeches and Mannerheim's response and therefore placed microphones in some of the railway cars. However, Mannerheim and his guests chose to go to a car that did not have a microphone in it. Damen acted quickly, pushing a microphone through one of the car windows onto a net shelf just above where Hitler and Mannerheim were sitting. After eleven minutes of Hitler's and Mannerheim's private conversation, Hitler's SS bodyguards spotted the cords coming out of the window and realized that the Finnish engineer was recording the conversation. They gestured to him to stop recording immediately, and he complied. The SS bodyguards demanded that the tape be destroyed, but Yleisradio was allowed to keep the reel after promising to keep it in a sealed container. It was given to Kustaa Vilkuna, head of the state censors' office, and in 1957 returned to Yleisradio. It was released to the public a few years later. It is the only known recording of Hitler speaking outside of a formal occasion.[71][72]

There is an unsubstantiated story that while conversing with Hitler, Mannerheim lit a cigar. Mannerheim expected that Hitler would ask Finland for more help against the Soviet Union, which Mannerheim was unwilling to give. When Mannerheim lit up, all in attendance gasped, for Hitler's aversion to smoking was well known. Nevertheless, Hitler continued the conversation calmly, with no comment. By this test, Mannerheim could judge if Hitler was speaking from a position of strength or weakness. He refused Hitler, knowing that Hitler was in a weak position, and could not dictate to him.[61][62]

Shortly thereafter, Mannerheim returned the visit, traveling to Hitler's headquarters in East Prussia.[73]

End of war and presidency

In June 1944, Baron Gustaf Mannerheim, to ensure German support while a major Soviet offensive was threatening Finland, thought it necessary to agree to the pact the German Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop demanded. But even then Mannerheim distanced himself from the pact, and it fell to President Risto Ryti to sign it, so it came to be known as the Ryti-Ribbentrop Agreement. This allowed Mannerheim to revoke the agreement upon the resignation of President Ryti at the start of August 1944. Mannerheim succeeded Ryti as president.[61][74]

When Germany was deemed sufficiently weakened, and the USSR's summer offensive was fought to a standstill (see Battle of Tali-Ihantala) thanks to the June agreement with the Germans, Finland's leaders saw a chance to reach a peace with the Soviet Union.[75] At first, attempts were made to persuade Mannerheim to become prime minister, but he rejected them because of his age and lack of experience running a civil government. The next suggestion was to elect him head of state. Risto Ryti would resign as president, and parliament would appoint Mannerheim as regent. The use of the title regent would have reflected the exceptional circumstances of Mannerheim's election. Mannerheim and Ryti both agreed, and Ryti submitted a notice of resignation on 1 August. The Parliament of Finland passed a special act conferring the presidency on Mannerheim on 4 August 1944. He took the oath of office the same day.[61][74]

A month after Mannerheim took office, the Continuation War was concluded on harsh terms, but ultimately far less harsh than those imposed on the other states bordering the Soviet Union. Finland retained its sovereignty, its parliamentary democracy, and its market economy. Territorial losses were considerable; a portion of Karelia and all Petsamo were lost. Numerous Karelian refugees needed to be relocated. The war reparations were very heavy. Finland also had to fight the Lapland War against withdrawing German troops in the north, and at the same time demobilize its own army, making it harder to expel the Germans;[76] Mannerheim appointed Lieutenant General Hjalmar Siilasvuo as the high commander of the army to take this action.[77][78] It is widely agreed that only Mannerheim could have guided Finland through these difficult times, when the Finnish people had to come to terms with the severe conditions of the armistice, their implementation by a Soviet-dominated Allied Control Commission, and the task of post-war reconstruction.[74]

Before deciding to accept the Soviet demands, Mannerheim wrote a missive directly to Hitler:[79]

Our German brothers-in-arms will forever remain in our hearts. The Germans in Finland were certainly not the representatives of foreign despotism but helpers and brothers-in-arms. But even in such cases foreigners are in difficult positions requiring such tact. I can assure you that during the past years nothing whatsoever happened that could have induced us to consider the German troops intruders or oppressors. I believe that the attitude of the German Army in northern Finland towards the local population and authorities will enter our history as a unique example of a correct and cordial relationship ... I deem it my duty to lead my people out of the war. I cannot and I will not turn the arms which you have so liberally supplied us against Germans. I harbour the hope that you, even if you disapprove of my attitude, will wish and endeavour like myself and all other Finns to terminate our former relations without increasing the gravity of the situation.

Mannerheim's term as president was difficult for him. Although he was elected for a full six-year term, he was 77 years old in 1944 and had accepted the office reluctantly after being urged to do so. The situation was exacerbated by frequent periods of ill-health, the demands of the Allied Control Commission, and the war responsibility trials. He was afraid throughout most of his presidency that the commission would request that he be prosecuted for crimes against peace. This never happened. One of the reasons for this was Stalin's respect for and admiration of the Marshal. Stalin told a Finnish delegation in Moscow in 1947 that the Finns owed much to their old Marshal. Due to Mannerheim, Finland was not occupied.[80] Despite Mannerheim's criticisms of some of the demands of the Control Commission, he worked hard to carry out Finland's armistice obligations. He also emphasised the necessity of further work on reconstruction in Finland after the war.[61][74]

Mannerheim was troubled by recurring health problems during 1945, and was absent on medical leave from his duties as president from November until February 1946. He spent six weeks in Portugal to restore his health.[81] After the announcement of the verdicts in the war crimes trials in February, Mannerheim decided to resign. He believed that he had accomplished the duties he had been elected to carry out: The war was ended, the armistice obligations carried out, and war responsibility trials finished.

Mannerheim resigned as president on 11 March 1946, giving as his reason his declining health and his view that the tasks he had been selected to carry out had been accomplished. He was succeeded as president by the conservative Prime Minister J. K. Paasikivi.[74]

Final days and death

After his resignation, Marshal Baron Mannerheim bought Kirkniemi Manor in Lohja, intending to spend his retirement there. In June 1946, he underwent an operation for a perforated peptic ulcer, and in October of that year he was diagnosed with a duodenal ulcer. In early 1947, it was recommended that he should travel to the Valmont Sanatorium in Montreux, Switzerland, to recuperate and write his memoirs. Valmont was to be Mannerheim's main residence for the remainder of his life, although he regularly returned to Finland, and also visited Sweden, France and Italy.[82]

Because Mannerheim was old and sickly, he personally wrote only certain passages of his memoirs. Some other parts he dictated. The remaining parts were written from his recollections by Mannerheim's various assistants, such as Colonel Aladár Paasonen; General Erik Heinrichs; Generals Grandell, Olenius and Martola; and Colonel Viljanen, a war historian. As long as Mannerheim was able to read, he proofread the typewritten drafts of his memoirs. He was almost totally silent about his private life, and focused instead on Finland's history, especially between 1917 and 1944. When Mannerheim suffered a fatal bowel obstruction in January 1951,[83] his memoirs were not yet in their finished form. They were published after his death.[54]

Mannerheim died on 27 January 1951 (28 January Finnish time), in the Cantonal Hospital in Lausanne (French: L'Hôpital cantonal à Lausanne; modern Lausanne University Hospital[84]), Switzerland. He was buried on 4 February 1951 in the Hietaniemi Cemetery in Helsinki in a state funeral with full military honours.

Legacy

Today, Mannerheim retains respect as Finland's greatest statesman. This may be partly due to his refusal to enter partisan politics (although his sympathies were more right-wing than left-wing), his claim always to serve the fatherland without selfish motives, his personal courage in visiting the frontlines, his ability to work diligently into his late seventies, and his foreign political farsightedness in preparing for the Soviet invasion of Finland years before it occurred.[61] Although Finland fought alongside Nazi Germany during the Continuation War and thus in co-operation with the Axis Powers, a surprising number of leaders of the Allies respected Mannerheim. These included, among others, the then British Prime Minister Winston Churchill; at a 2017 conference in London, war historian Terry Charman said it was difficult for Churchill to declare war on Finland at Stalin's demand due to his previous uncomplicated co-operation with Mannerheim, which led Churchill and Mannerheim to exchange polite and apologetic correspondence about the prevailing circumstance, yet with deep respect for each other.[85]

Mannerheim's birthday, 4 June, is celebrated as Flag Day by the Finnish Defence Forces. This decision was made by the Finnish government on the occasion of his 75th birthday in 1942, when he was also granted the title of Marshal of Finland. Flag Day is celebrated with a national parade, and rewards and promotions for members of the defence forces. The life and times of Mannerheim are memorialised in the Mannerheim Museum.[55] The most prominent boulevard in the Finnish capital was renamed Mannerheimintie (Mannerheim Road) in the Marshal's honour during his lifetime; along the road, at the Kamppi district, stands Hotel Marski, which is named after him. Mannerheim's former hunting lodge and resting place known as the "Marshal's Cabin" (Marskin Maja), which now serves as both a museum and a restaurant, is located at the shores of Lake Punelia in Loppi, Finland.[86]

Various landmarks across Finland honour Mannerheim, including most famously the Equestrian statue located on Helsinki's Mannerheimintie in front of the later-built Kiasma museum of modern art. Both Mannerheim Parks in Turku and Seinäjoki includes a statues of him. Tampere's Mannerheim statue depicting the victorious Civil War general of the Whites was eventually placed in the forest some kilometres outside the city (in part due to lingering controversy over Mannerheim's Civil War role). Other statues, for examples, were erected in Mikkeli and Lahti.[87] On 5 December 2004, Mannerheim was voted the greatest Finnish person of all time in the Suuret suomalaiset (Great Finns) contest.[6]

In June 2016 a memorial plaque of Mannerheim was installed in St. Petersburg on the facade of the building where unit led by him once resided[88] to commemorate his service as a senior officer in the Russian army. However, this move was considered controversial by a part of the public, due to Mannerheim's role in World War II: while he refused to attack St. Petersburg (then Leningrad), his army still participated in city's blockade. After the plaque suffered multiple acts of vandalism,[89] it was removed in October 2016 to be relocated to the Museum of the First World War in Tsarskoye Selo.[90]

From 1937 to 1967, at least five different Finnish postage stamps or stamp series were issued in honour of Mannerheim; and in 1960 the United States honoured Mannerheim as the "Liberator of Finland" with regular first-class envelope domestic and international stamps (at the time four cents and eight cents respectively) as part of its Champions of Liberty series that included other notable figures such as Mahatma Gandhi and Simon Bolivar.[91][92][93]

Mannerheim appears as a main character in Ilmari Turja's 1966 play and its the 1970 film adaptation Päämaja, directed by Matti Kassila. In both the play and the film, Mannerheim was played by Joel Rinne.[94] Mannerheim was also played by Asko Sarkola in the 2001 television film Valtapeliä elokuussa 1940, directed by Veli-Matti Saikkonen.[95] Director Renny Harlin and producer Markus Selin were planned a biographical film about Mannerheim for a long time in the 21st century, and Mikko Nousiainen was attached to Mannerheim's role in the film. However, due to financial difficulties related to the production of the film, the project was canceled.[96][97] A loosely based Finnish-Kenyan co-production The Marshal of Finland was released in 2012, and it takes place in Kenya. In the film, Mannerheim is played by Telley Savalas Otieno.[98] A 2008 animated short film The Butterfly from Ural, directed by Katariina Lillqvist, tells a story of Mannerheim – although his name is not mentioned in the film – on a journey to Central Asia where he meets a young Kyrgyz boy. The film caused a fuss in the Finnish media and evoked discussion about the limits of the freedom of speech and the sexual orientation of Mannerheim.[99] This may have been take inspiration from the controversial claims made as the late 19th century about Mannerheim's homosexuality, for which there is no conclusive evidence.[100][101] A 2008 historical novel Troikka by Jari Tervo tells the fictional story of the background to the 1920 assassination attempt on Mannerheim.[102]

The most significant cases mentioned in Mannerheim's reputed relationship was Yekaterina Geltzer, a ballerina at the Mariinsky Theatre, who after the Russian Revolution became the first red star ballerina in the Soviet Union at the Bolshoi Theatre.[103][104][105] For years, there has been a rumor in Russia that Mannerheim and Geltser would have secretly married, accidentally ended up apart, and jointly had a "son" Emil,[106][107] whose descendants would still live in South America today, but Mannerheim scholars have only reacted negatively and characterized the claim just a "Russian fairy tale."[106] Writers and the media have also been interested in Mannerheim's romantic relationship with Catharina "Kitty" Linder. In 2013, an article about Kitty Linder and Mannerheim was published in the monthly supplement of Helsingin Sanomat.[108] In 2017, the character "Kitty" has appeared as Mannerheim's bride in Juha Vakkuri's novel Mannerheim ja saksalainen suudelma (literally "Mannerheim and the German Kiss").[109]

Military ranks

In the Russian Army

- 1888: Non-commissioned officer

- 1889: Cornet

- 1891: Cornet of the Guard

- 1893: Lieutenant of the Guard

- 1902: Captain of the Guard

- 1904: Lieutenant Colonel

- 1905: Colonel

- 1911: Major General

- 1917: Lieutenant General

In the Finnish Army

- 1918: General of Cavalry

- 1933: Field Marshal

- 1942: Marshal of Finland

Supreme Command

- 1918: Commander-in-Chief of the White Guard: from January to May 1918

- 1918: Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Defence Forces: from December 1918 to July 1919

- 1931: Chairman of the Defence Council: from 1931 to 1939

- 1939: Commander-in-Chief of the Finnish Defence Forces [bis]: from 1939 to 1946

Awards

| Coat of Arms of Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim | |

|---|---|

| |

| Armiger | Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim |

| Motto | "Candida pro causa ense candido"[110]("With an honourable sword for an honourable cause") |

In the course of his lifetime, Mannerheim received 82 military and civilian decorations.[111]

Finland

Commander Grand Cross with Swords and Diamonds of the Order of the Cross of Liberty (1940; Commander Grand Cross with Swords: 1918)

Commander Grand Cross with Swords and Diamonds of the Order of the Cross of Liberty (1940; Commander Grand Cross with Swords: 1918) Knight of the Mannerheim Cross, 1st and 2nd class, the Order of the Cross of Liberty (1941)

Knight of the Mannerheim Cross, 1st and 2nd class, the Order of the Cross of Liberty (1941) Commander Grand Cross, with Collar, Swords and Diamonds, of the Order of the White Rose (1944)

Commander Grand Cross, with Collar, Swords and Diamonds, of the Order of the White Rose (1944) Commander Grand Cross, with Swords and Diamonds, of the Order of the Lion of Finland (1944)

Commander Grand Cross, with Swords and Diamonds, of the Order of the Lion of Finland (1944)

Russian Empire

Order of St. Anna, 2nd degree (1906)

Order of St. Anna, 2nd degree (1906) Order of St. Stanislaus, 2nd class (1906)

Order of St. Stanislaus, 2nd class (1906) Order of St. Vladimir, 4th degree (1906)

Order of St. Vladimir, 4th degree (1906) Order of St. George, Knight 4th class (1914)

Order of St. George, Knight 4th class (1914)

Sweden

Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword (1918)

Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Sword (1918) Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim (1919)

Knight of the Royal Order of the Seraphim (1919) Knight Grand Cross 1st Class of the Order of the Sword (1942)

Knight Grand Cross 1st Class of the Order of the Sword (1942)

Others

Denmark: Knight of the Order of the Elephant (1919)

Denmark: Knight of the Order of the Elephant (1919) France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (1939; Officer: 1910; Knight: 1902)

France: Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour (1939; Officer: 1910; Knight: 1902) Estonia: Military Order of the Cross of the Eagle, 1st Class with Swords (1930)

Estonia: Military Order of the Cross of the Eagle, 1st Class with Swords (1930) Estonia: Grand Cross of Order of the Estonian Red Cross (1933)

Estonia: Grand Cross of Order of the Estonian Red Cross (1933).svg.png.webp) German Empire: Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class (1918)

German Empire: Iron Cross 1st and 2nd Class (1918) Kingdom of Hungary: Order of Merit of the Kingdom of Hungary, Grand Cross with the Holy Crown of St. Stephen (1941)

Kingdom of Hungary: Order of Merit of the Kingdom of Hungary, Grand Cross with the Holy Crown of St. Stephen (1941) Japan: Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers, Grand Cordon.[112]

Japan: Order of the Rising Sun with Paulownia Flowers, Grand Cordon.[112].svg.png.webp) Nazi Germany: Golden Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle

Nazi Germany: Golden Grand Cross of the Order of the German Eagle.svg.png.webp) Nazi Germany: Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves (1944; Knight's Cross: 1942; Iron Cross 1st Class with 1939 bar: 1942)

Nazi Germany: Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves (1944; Knight's Cross: 1942; Iron Cross 1st Class with 1939 bar: 1942) Kingdom of Romania: Order of Michael the Brave, 1st class (1941)

Kingdom of Romania: Order of Michael the Brave, 1st class (1941) United Kingdom: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE) (1938)

United Kingdom: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire (GBE) (1938)

Works

- C.G. Mannerheim, Across Asia From West to East in 1906–1908. (1969) Anthropological Publications. Oosterhout N.B. – The Netherlands

- Across Asia : Vol. 1 – digital images

See also

- Adolf Ehrnrooth

- Hitler and Mannerheim recording

- Johan Laidoner

- List of wars involving Finland

- Mannerheim Cross

- Mannerheim Line

- Mannerheim Museum

- Mannerheim Park

- Mannerheimintie

- Marshal's Cabin

- The Marshal of Finland (film)

- Marskin ryyppy

- Vorschmack

References

- Everyman's Encyclopedia volume 8. J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd. 1978. ISBN 0-460-04020-0.

- Riku Keski-Rauska (2005). Georg C. Ehrnrooth – Kekkosen kauden toisinajattelija (in Finnish). Helsinki: University of Helsinki.

- C. G. E. Mannerheim at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- Klinge, Matti. "Mannerheim, Gustaf (1867–1951)". National Biography of Finland. Retrieved 21 April 2017.

- Zeiler, Thomas W.; DuBois, Daniel M., eds. (2012). "Scandinavian Campaigns". A Companion to World War II. Wiley Blackwell Companions to World History. Vol. 11. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-9681-9.

- (in Finnish) Suuret suomalaiset at YLE.fi

- Edwards, Robert, ed. (2007). White Death: Russia's War with Finland 1939–1940. Phoenix. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-7538-2247-0.

- Warner, Oliver (1967) Marshal Mannerheim and the Finns, Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 154 ff.

- Binder, David (16 October 1983). "Finland's Heritage on parade". The New York Times. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "Field Marshal Mannerheim, THE FATHER OF FINLAND". 15 November 1945. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "Finland Country Profile – Timeline". BBC News. 25 September 2012. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- Jokelin, Jantso (4 June 2017). "Punikkisuvun lapsi puuskahtaa: Antakaa Marskille jo se suurmieselokuva". Aamulehti (in Finnish). Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- HS: Muodikas Marski (in Finnish).

- "Mannerheimin suku onkin lähtöisin Saksasta". kaleva.fi. 1 March 2007. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- "Mannerheimin suku onkin lähtöisin Saksasta". mtv3.fi. March 2007.

- Johan Augustin Mannerheim Archived 29 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine. tjelvar.se (in Swedish)

- Muotokuva; Johan Augustin Mannerheim; (1706–1778). finna.fi (in Finnish)

- Meri (1990), pp. 107–108.

- Meri (1990), p. 108.

- IS: Pikavippi olisi kelvannut Mannerheimillekin (in Finnish)

- Jägerskiöld (1965), pp. 68–70.

- Jägerskiöld (1965), pp. 93–94.

- Meri (1990), p. 123.

- Meri (1990), p. 129.

- Screen (1970), p. 33.

- "Краткие сведения об офицерах-Александрийцах: Великая война, Гражданская война, эмиграция. Часть 2-я (фамилии К – Р). – Статьи – Каталог статей – 5-й Гусарский Александрийский полк". blackhussars.ucoz.ru.

- Meri (1990), pp. 145–147.

- Pallaste, Tuija (4 November 2017). "Mannerheimin tyttärien vaietut elämät: hauras Stasie eli nunnana ja levoton Sophy pakeni Pariisiin – lopulta kumpikin eli suhteessa naisen kanssa". Helsingin Sanomat. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Meri (1990), pp. 148–149.

- Trotter (2013), p. 24.

- Clements (2009), p. 40.

- Jägerskiöld (1986).

- Elina Koivunen: Carl Gustaf Mannerheim – Suomen historian myyttisin mies, Kotiliesi s. 82–85, nro 12/15.6.2010 (in Finnish)

- Screen (1970), pp. 43–49.

- Clements (2009), pp. 80–81.

- "Mannerheim halusi diktaattoriksi ja lähes sai haluamansa". Iltalehti (in Finnish). 27 January 2021. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- "Horse That Leaps Through Clouds – Retracing Mannerheim's Journey Across Asia". horsethatleaps.com.

- Caldwell, Christopher (11 August 2017). "Start to Finnish". Washington Examiner. Retrieved 4 February 2020.

It was an 8,000-mile spying expedition. Russia was drawing up plans to invade China from the west—but failed to.

- Clements (2009), pp. 100–103.

- Tamm, Eric Enno (2010). The Horse That Leaps Through Clouds: A Tale of Espionage, the Silk Road and the Rise of Modern China. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. ISBN 978-1-55365-269-4.

- Trotter (2013), p. 29.

- "Horse That Leaps Through Clouds – Retracing Mannerheim's Journey Across Asia". horsethatleaps.com.

- "Horse That Leaps Through Clouds – Retracing Mannerheim's Journey Across Asia". horsethatleaps.com.

- "Mannerheim tapasi Dalai-laman". Kaleva (in Finnish). Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- Clements (2009), p. 155.

- Putensen, Dörte (2017). "Der größte Finne aller Zeiten?". Damals (in German). No. 5. pp. 72–76.

- Harald Haarmann (2016). Modern Finland. p. 122.

- Screen (2000), p. 9.

- Mannerheim (1953), p. 138.

- Mannerheim (1953), p. 184.

- Meri (1990), p. 104.

- Mannerheim ei ollut koko valkoisen Suomen sankari – Turun Sanomat (in Finnish)

- Virkkunen, Sakari (1992). Mannerheimin kääntöpuoli. Helsingissä: Otava.

- Jägerskiöld (1983).

- Mannerheim-Museo.fi Archived 13 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Screen (2000), pp. 90–97.

- Manninen, Tuomas (10 December 2020). "Tutkija: Mannerheim oli kolonialisti, kun ampui tiikereitä norsun päältä – tällaisia olivat Intian-matkat, joihin marsalkka osallistui "valkoisen metsästäjän roolissaan"". Ilta-Sanomat (in Finnish). Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Pietiläinen, Jari (7 October 2022). "Omatkin halusivat tappaa Mannerheimin – Uutta tietoa: tällaisia murhayrityksiä aikalaiset juonivat marsalkan päänmenoksi". Nurmijärven Uutiset (in Finnish). Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- Screen (2000), p. 104.

- Screen (2000), p. 112.

- Virkkunen, Sakari (1994) "Presidents of Finland II" (Suomen presidentit II), published in Finland

- Turtola (1994).

- Mannerheimin murhayrityksen jälkinäytös käytiin Vallilassa (in Finnish)

- Mikko Porvali : Murhayritys joka jäi tekemättä (in Finnish)

- Murhahankkeet kenraali Mannerheimia ja sotaministeri Jalanderia vastaan, Aamulehti July 24, 1920, no. 167, p. 5. (in Finnish)

- Uusi Pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish). WSOY. 1986. p. 1022. ISBN 951-0-12416-8.

- Mannerheim kuuli Hitlerin saapuvan syntymäpäiväjuhliin: – "Vad i helvete gör han här?" (in Finnish)

- Uutuuskirja: Mannerheim innostui aluksi Hitleristä (in Finnish)

- Jacobsson (1999).

- Mannerheim (1953), p. 456.

- Helsingin Sanomat International Web-Edition Archived 19 August 2014 at the Wayback Machine – "Conversation secretly recorded in Finland helped a German actor prepare for Hitler role" Helsingin Sanomat / First published in print 15 September 2004 in Finnish.

- Recording available Yle's web-archive

- Mannerheim (1953), pp. 454–455.

- Zetterberg, Seppo et al., eds. (2003) "A Small Giant of Finnish History" (Suomen historian pikkujättiläinen)

- Screen (2000), p. 205.

- Kinnunen, Tiina; Kivimäki, Ville, eds. (2011). Finland in World War II: History, Memory, Interpretations. p. 87. ISBN 978-9004208940.

- Ilkka Enkenberg: Lapin sodan alku (in Finnish)

- YLE Elävä arkisto: Lapin sodan tuhot (in Finnish)

- Nenye, Vesa; Munter, Peter; Wirtanen, Toni; Birks, Chris (2016). Finland at War: the Continuation and Lapland Wars 1941–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1472815262.

- Meri (1990), p. 397.

- Hinkkanen, Tomi (4 June 2021). "Raihnainen Mannerheim teki salaperäisen matkan Portugaliin, rantaloman aikana kaikkosi riski sotasyyllisyystuomiosta". Suomen Kuvalehti (in Finnish). Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Screen (2000), p. 245.

- Screen (2000), pp. 252.

- "Historique". Centre hospitalier universitaire vaudois. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- Cunningham, Marjo (5 November 2017). "Churchill kehui Mannerheimia: "Todellinen mies – vahva kuin kallionjärkäle"". Suomen Kuvalehti (in Finnish). Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "Marskin Maja" lodge – Häme Lake Uplands – Visit Loppi

- Matti Klinge, transl. Roderick Fletcher. "Mannerheim, Gustaf (1867–1951) President of Finland, Marshal of Finland". Biografiakeskus. Retrieved 12 September 2013.

- "Mannerheim memorial raises hackles in Russia". yle.fi. 9 August 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- "Memorial plaque to ex-Finnish president hacked with ax in St. Petersburg". Meduza. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- "Controversial St. Petersburg Memorial Removed". The Moscow Times. 14 October 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2021.

- "MANNERHEIM – Special Topics – Stamps". www.mannerheim.fi.

- "8-cent Mannerheim". 12 December 2008. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- "50th Anniversary USA Champions of Liberty Mahatma Gandhi Stamp". 9 March 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- Päämaja – Finna.fi (in Finnish)

- Valtapeliä elokuussa 1940 (TV Movie 2001) – IMDb

- Veli-Pekka Lehtonen, Harlin jätti Mannerheim-elokuvan, Selin jatkaa, Helsingin Sanomat 22.5.2011 sivu C 3 (in Finnish)

- Veli-Pekka Lehtonen, Renny Harlinille maksettiin valmistumattomasta Mannerheim-elokuvasta 700 000 euron palkkio (Archive.org) Helsingin Sanomat 24.2.2014 (in Finnish)

- Official website (in Finnish)

- HS.fi: Katariina Lillqvist tekee nukeilla poliittista taidetta Archived 17 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine (in Finnish)

- The 'Greatest Finn' meets the 'Gay Marshal'

- IL: Pimeä historia: Epäilyt Mannerheimin homoudesta alkoivat pääsiäisenä 1886 (in Finnish)

- Tervo tarttuu Mannerheimin vaiettuun murhayritykseen (in Finnish)

- Clements, 2009.

- Mannerheim's life years: Finnish army commander – Ik-ptz.ru

- YLE: Juonittelua, happohyökkäyksiä, itsemurhia – nämä skandaalit ovat värittäneet Suomessa vierailevaa venäläistä Bolshoi-teatteria (in Finnish)

- IS: Venäjällä leviää ”satu” Mannerheimista – meni muka naimisiin punaisen ballerinan kanssa, pojanpoika tuli Suomeen Hitlerin kanssa (in Finnish)

- Kuka on Mannerheim ja mikä oli hänen linjansa?

- Pallaste, Tuija. "Rakkaudella, Gustaf". HS.fi (in Finnish). Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Ruuska, Helena (27 October 2017). "Kirja-arvostelu: Juha Vakkurin romaani kaivelee Mannerheimin sotilasuran kipeitä kohtia" (in Finnish). Helsingin Sanomat. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- "Gustaf Mannerheim The Marshal of Finland". mannerheim-museo.fi. Archived from the original on 19 January 2020. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- Mannerheim Internetprojekti, kunniamerkit valokuvineen (Finnish)

- No. 77, Nousevan Auringon Ritarikunnan I luokka Paulovniakukkasin, Japani, mannerheim.fi.

Bibliography

- Clements, Jonathan (2009). Mannerheim: President, Soldier, Spy. London: Haus Publishing. ISBN 978-1907822575.

- Jägerskiöld, Stig (1965). Nuori Mannerheim.

- Jägerskiöld, Stig (1983). Mannerheim 1867–1951. Helsinki: Otava Publications.

- Jägerskiöld, Stig (1986). Mannerheim: Marshal of Finland. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1527-6.

- Koskikallio, Petteri. Asko Lehmuskallio, and Harry Halén. C. G. Mannerheim in Central Asia 1906–1908. Helsinki: National Board of Antiquities, 1999. ISBN 951-616-048-4.

- Jacobsson, Max (1999). Century of Violence.

- Warner, Oliver. "Mannerheim, Marshal of Finland, 1867–1951" History Today (July 1964) 14#7 pp 461–468.

- Mannerheim, Carl Gustaf Emil (1953). The Memoirs of Marshal Mannerheim. London: Cassell. OCLC 12424452., primary source

- Meri, Veijo (1990). Suomen marsalkka C. G. Mannerheim.

- Screen, J. E. O. (1970). Mannerheim: The Years of Preparation. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. ISBN 0-900966-22-X.

- Screen, J. E. O. (2000). Mannerheim: The Finnish Years. London: Hurst. ISBN 1-85065-573-1.

- Trotter, William (2013). A Frozen Hell: The Russo-Finnish Winter War of 1939–1940. Chapel Hill: Algonquin Books. ISBN 9781565126923.

- Turtola, Martti (1994). Risto Ryti: A Life for the Fatherland. Risto Ryti: Elämä isänmaan puolesta. Helsinki: Otava.

- Tyni, Mikko (2022). Marsalkan muskettisoturit – Mannerheimin henkivartiointi ja turvallisuus 1918–1946. Jyväskylä: Docendo. ISBN 9789523823891.

External links

- "Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim". Biografiskt lexikon för Finland (in Swedish). Helsingfors: Svenska litteratursällskapet i Finland. urn:NBN:fi:sls-4132-1416928956738.

- Mannerheim's Journey Across Asia including interactive Google maps, slide shows, videos and more

- C. G. E. Mannerheim in the history of Finland

- Mannerheim Museum

- Audio recordings of Hitler and Mannerheim's public and private talk (w/English text on YouTube), 4 June 1942

- (in Finnish and Swedish) Mannerheim's 1944 inauguration address

- On Mannerheim's role in defending Jews

- Mannerheim League for Child Welfare English website

- Newspaper clippings about Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW

- C. G. E. Mannerheim in The Presidents of Finland