Camera

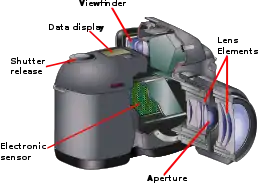

A camera is an optical instrument that can capture an image. Most cameras can capture 2D images, with some more advanced models being able to capture 3D images. At a basic level, most cameras consist of sealed boxes (the camera body), with a small hole (the aperture) that allows light to pass through through in order to capture an image on a light-sensitive surface (usually a digital sensor or photographic film). Cameras have various mechanisms to control how the light falls onto the light-sensitive surface. Lenses focus the light entering the camera, and the aperture can be narrowed or widened. A shutter mechanism determines the amount of time the photosensitive surface is exposed to the light.

The still image camera is the main instrument in the art of photography. Captured images may be reproduced later as part of the process of photography, digital imaging, or photographic printing. Similar artistic fields in the moving-image camera domain are film, videography, and cinematography.

The word camera comes from camera obscura, the Latin name of the original device for projecting a 2D image onto a flat surface (literally translated to "dark chamber"). The modern photographic camera evolved from the camera obscura. The first permanent photograph was made in 1825 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce.[1]

Mechanics

Most cameras capture light from the visible spectrum, while specialized cameras capture other portions of the electromagnetic spectrum, such as infrared.[2]: vii

All cameras use the same basic design: light enters an enclosed box through a converging or convex lens and an image is recorded on a light-sensitive medium.[3] A shutter mechanism controls the length of time that light enters the camera.[4]: 1182–1183

Most cameras also have a viewfinder, which shows the scene to be recorded, along with means to adjust various combinations of focus, aperture and shutter speed.[5]: 4

Aperture

Light enters the camera through an aperture, an opening adjusted by overlapping plates called the aperture ring.[6][7][8] Typically located in the lens,[9] this opening can be widened or narrowed to alter the amount of light that strikes the film or sensor.[6] The size of the aperture can be set manually, by rotating the lens or adjusting a dial, or automatically based on readings from an internal light meter.[6]

As the aperture is adjusted, the opening expands and contracts in increments called f-stops.[lower-alpha 1][6] The smaller the f-stop, the more light is allowed to enter the lens, increasing the exposure. Typically, f-stops range from f/1.4 to f/32[lower-alpha 2] in standard increments: 1.4, 2, 2.8, 4, 5.6, 8, 11, 16, 22, and 32.[10] The light entering the camera is halved with each increasing increment.[9]

The wider opening at lower f-stops narrows the range of focus so the background is blurry while the foreground is in focus. This depth of field increases as the aperture closes. A narrow aperture results in a high depth of field, meaning that objects at many different distances from the camera will appear to be in focus.[11] What is acceptably in focus is determined by the circle of confusion, the photographic technique, the equipment in use and the degree of magnification expected of the final image.[12]

Shutter

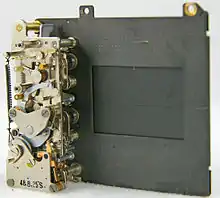

The shutter, along with the aperture, is one of two ways to control the amount of light entering the camera. The shutter determines the duration that the light-sensitive surface is exposed to light. The shutter opens, light enters the camera and exposes the film or sensor to light, and then the shutter closes.[9][13]

There are two types of mechanical shutters: the leaf-type shutter and the focal-plane shutter. The leaf-type uses a circular iris diaphragm maintained under spring tension inside or just behind the lens that rapidly opens and closes when the shutter is released.[10]

More commonly, a focal-plane shutter is used.[9] This shutter operates close to the film plane and employs metal plates or cloth curtains with an opening that passes across the light-sensitive surface. The curtains or plates have an opening that is pulled across the film plane during exposure. The focal-plane shutter is typically used in single-lens reflex (SLR) cameras, since covering the film (rather than blocking the light passing through the lens) allows the photographer to view the image through the lens at all times, except during the exposure itself. Covering the film also facilitates removing the lens from a loaded camera, as many SLRs have interchangeable lenses.[6][10]

A digital camera may use a mechanical or electronic shutter, the latter of which is common in smartphone cameras. Electronic shutters either record data from the entire sensor at the same time (a global shutter) or record the data line by line across the sensor (a rolling shutter).[6] In movie cameras, a rotary shutter opens and closes in sync with the advancement of each frame of film.[6][14]

The duration for which the shutter is open is called the shutter speed or exposure time. Typical exposure times can range from one second to 1/1,000 of a second, though longer and shorter durations are not uncommon. In the early stages of photography, exposures were often several minutes long. These long exposure times often resulted in blurry images, as a single object is recorded in multiple places across a single image for the duration of the exposure. To prevent this, shorter exposure times can be used. Very short exposure times can capture fast-moving action and eliminate motion blur.[15][10][6][9] However, shorter exposure times require more light to produce a properly exposed image, so shortening the exposure time is not always possible.

Like aperture settings, exposure times increment in powers of two. The two settings determine the exposure value (EV), a measure of how much light is recorded during the exposure. There is a direct relationship between the exposure times and aperture settings so that if the exposure time is lengthened one step, but the aperture opening is also narrowed one step, then the amount of light that contacts the film or sensor is the same.[9]

Metering

In most modern cameras, the amount of light entering the camera is measured using a built-in light meter or exposure meter.[lower-alpha 3] Taken through the lens (called TTL metering), these readings are taken using a panel of light-sensitive semiconductors.[7] They are used to calculate optimal exposure settings. These settings are typically determined automatically as the reading is used by the camera's microprocessor. The reading from the light meter is incorporated with aperture settings, exposure times, and film or sensor sensitivity to calculate the optimal exposure. [lower-alpha 4]

Light meters typically average the light in a scene to 18% middle gray. More advanced cameras are more nuanced in their metering—weighing the center of the frame more heavily (center-weighted metering), considering the differences in light across the image (matrix metering), or allowing the photographer to take a light reading at a specific point within the image (spot metering).[11][15][16][6]

Lens

The lens of a camera captures light from the subject and focuses it on the sensor. The design and manufacturing of the lens are critical to photo quality. A technological revolution in camera design during the 19th century modernized optical glass manufacturing and lens design. This contributed to the modern manufacturing processes of a wide range of optical instruments such as reading glasses and microscopes. Pioneering companies include Zeiss and Leitz.

Camera lenses are made in a wide range of focal lengths, such as extreme wide angle, standard, and medium telephoto. Lenses either have a fixed focal length (prime lens) or a variable focal length (zoom lens). Each lens is best suited to certain types of photography. Extreme wide angles might be preferred for architecture due to their ability to capture a wide view of buildings. Standard lenses commonly have a wide aperture, and because of this, they are often used for street and documentary photography. The telephoto lens is useful in sports and wildlife but is more susceptible to camera shake, which might cause motion blur.[17]

Focus

Due to the optical properties of a photographic lens, only objects within a limited range of distance from the camera will be reproduced clearly. The process of adjusting this range is known as changing the camera's focus. There are various ways to accurately focus a camera. The simplest cameras have fixed focus and use a small aperture and wide-angle lens to ensure that everything within a certain range of distance from the lens, usually around 3 meters (10 ft.) to infinity, is in reasonable focus. Fixed focus cameras are usually inexpensive, such as single-use cameras. The camera can also have a limited focusing range or scale-focus that is indicated on the camera body. The user will guess or calculate the distance to the subject and adjust the focus accordingly. On some cameras, this is indicated by symbols (head-and-shoulders; two people standing upright; one tree; mountains).

Rangefinder cameras allow the distance to objects to be measured employing a coupled parallax unit on top of the camera, allowing the focus to be set with accuracy. Single-lens reflex cameras allow the photographer to determine the focus and composition visually using the objective lens and a moving mirror to project the image onto a ground glass or plastic micro-prism screen. Twin-lens reflex cameras use an objective lens and a focusing lens unit (usually identical to the objective lens) in a parallel body for composition and focus. View cameras use a ground glass screen which is removed and replaced by either a photographic plate or a reusable holder containing sheet film before exposure. Modern cameras often offer autofocus systems to focus the camera automatically by a variety of methods.[18]

Experimental cameras such as the planar Fourier capture array (PFCA) do not require focusing to take pictures. In conventional digital photography, lenses or mirrors map all of the light originating from a single point of an in-focus object to a single point at the sensor plane. Each pixel thus relates an independent piece of information about the far-away scene. In contrast, a PFCA does not have a lens or mirror, but each pixel has an idiosyncratic pair of diffraction gratings above it, allowing each pixel to likewise relate an independent piece of information (specifically, one component of the 2D Fourier transform) about the far-away scene. Together, complete scene information is captured, and images can be reconstructed by computation.

Some cameras support post-focusing. Post focusing refers to taking photos that are later focused on a computer. The camera uses many tiny lenses on the sensor to capture light from every camera angle of a scene, which is known as plenoptic technology. A current plenoptic camera design has 40,000 lenses working together to grab the optimal picture.[19]

Image capture on film

Traditional cameras capture light onto photographic plates, or photographic film. Video and digital cameras use an electronic image sensor, usually a charge-coupled device (CCD) or a CMOS sensor to capture images which can be transferred or stored in a memory card or other storage inside the camera for later playback or processing.

A wide range of film and plate formats have been used by cameras. In the early history plate sizes were often specific for the make and model of cameras although there quickly developed some standardization for the more popular cameras. The introduction of roll film drove the standardization process still further so that by the 1950s only a few standard roll films were in use. These included 120 films providing 8, 12 or 16 exposures, 220 films providing 16 or 24 exposures, 127 films providing 8 or 12 exposures (principally in Brownie cameras) and 135 (35mm film) providing 12, 20 or 36 exposures – or up to 72 exposures in the half-frame format or bulk cassettes for the Leica Camera range.

For cine cameras, film 35mm wide and perforated with sprocket holes was established as the standard format in the 1890s. It was used for nearly all film-based professional motion picture production. For amateur use, several smaller and therefore less expensive formats were introduced. 17.5mm film, created by splitting 35mm film, was one early amateur format, but 9.5mm film, introduced in Europe in 1922, and 16 mm film, introduced in the US in 1923, soon became the standards for "home movies" in their respective hemispheres. In 1932, the even more economical 8mm format was created by doubling the number of perforations in 16mm film, then splitting it, usually after exposure and processing. The Super 8 format, still 8mm wide but with smaller perforations to make room for substantially larger film frames, was introduced in 1965.

Film speed (ISO)

Traditionally used to tell the camera the film speed of the selected film on film cameras, film speed numbers are employed on modern digital cameras as an indication of the system's gain from light to numerical output and to control the automatic exposure system. Film speed is usually measured via the ISO 5800 system. The higher the film speed number, the greater the film sensitivity to light, whereas with a lower number, the film is less sensitive to light.[20]

White balance

In digital cameras, there is electronic compensation for the color temperature associated with a given set of lighting conditions, ensuring that white light is registered as such on the imaging chip and therefore that the colors in the frame will appear natural. On mechanical, film-based cameras, this function is served by the operator's choice of film stock or with color correction filters. In addition to using white balance to register the natural coloration of the image, photographers may employ white balance to aesthetic end—for example, white balancing to a blue object to obtain a warm color temperature.[21]

Flash

A flash provides a short burst of bright light during exposure and is a commonly used artificial light source in photography. Most modern flash systems use a battery-powered high-voltage discharge through a gas-filled tube to generate bright light for a very short time (1/1,000 of a second or less).[lower-alpha 5][16]

Many flash units measure the light reflected from the flash to help determine the appropriate duration of the flash. When the flash is attached directly to the camera—typically in a slot at the top of the camera (the flash shoe or hot shoe) or through a cable—activating the shutter on the camera triggers the flash, and the camera's internal light meter can help determine the duration of the flash.[16][11]

Additional flash equipment can include a light diffuser, mount and stand, reflector, soft box, trigger and cord.

Other accessories

Accessories for cameras are mainly used for care, protection, special effects, and functions.

- Lens hood: used on the end of a lens to block the sun or other light source to prevent glare and lens flare (see also matte box).

- Lens cap: covers and protects the camera lens when not in use.

- Lens adapter: allows the use of lenses other than those for which the camera was designed.

- Filter: allows artificial colors or changes light density.

- Lens extension tube: allows close focus in macro photography.

- Care and protection: include camera case and cover, maintenance tools, and screen protector.

- Camera monitor: provides an off-camera view of the composition with a brighter and more colorful screen, and typically exposes more advanced tools such as framing guides, focus peaking, zebra stripes, waveform monitors (oftentimes as an "RGB parade"), vectorscopes and false color to highlight areas of the image critical to the photographer.

- Tripod: primarily used for keeping the camera steady while recording video, doing a long exposure, and time-lapse photography.

- Microscope adapter: used to connect a camera to a microscope to photograph what the microscope is examining.

- Cable release: used to remotely control the shutter using a remote shutter button that can be connected to the camera via a cable. It can be used to lock the shutter open for the desired period, and it is also commonly used to prevent camera shake from pressing the built-in camera shutter button.

- Dew shield: prevents moisture build-up on the lens.

- UV filter: can protect the front element of a lens from scratches, cracks, smudges, dirt, dust, and moisture while keeping a minimum impact on image quality.

- Battery and sometimes a charger.

Large format cameras use special equipment that includes magnifier loupe, viewfinder, angle finder, and focusing rail/truck. Some professional SLRs can be provided with interchangeable finders for eye-level or waist-level focusing, focusing screens, eyecup, data backs, motor-drives for film transportation or external battery packs.

Primary types

Single-lens reflex (SLR) camera

.jpg.webp)

In photography, the single-lens reflex camera (SLR) is provided with a mirror to redirect light from the lens to the viewfinder prior to releasing the shutter for composing and focusing an image. When the shutter is released, the mirror swings up and away, allowing the exposure of the photographic medium, and instantly returns after the exposure is finished. No SLR camera before 1954 had this feature, although the mirror on some early SLR cameras was entirely operated by the force exerted on the shutter release and only returned when the finger pressure was released.[22][23] The Asahiflex II, released by Japanese company Asahi (Pentax) in 1954, was the world's first SLR camera with an instant return mirror.[24]

In the single-lens reflex camera, the photographer sees the scene through the camera lens. This avoids the problem of parallax which occurs when the viewfinder or viewing lens is separated from the taking lens. Single-lens reflex cameras have been made in several formats including sheet film 5x7" and 4x5", roll film 220/120 taking 8,10, 12, or 16 photographs on a 120 roll, and twice that number of a 220 film. These correspond to 6x9, 6x7, 6x6, and 6x4.5 respectively (all dimensions in cm). Notable manufacturers of large format and roll film SLR cameras include Bronica, Graflex, Hasselblad, Mamiya, and Pentax. However, the most common format of SLR cameras has been 35 mm and subsequently the migration to digital SLR cameras, using almost identical sized bodies and sometimes using the same lens systems.

Almost all SLR cameras use a front-surfaced mirror in the optical path to direct the light from the lens via a viewing screen and pentaprism to the eyepiece. At the time of exposure, the mirror is flipped up out of the light path before the shutter opens. Some early cameras experimented with other methods of providing through-the-lens viewing, including the use of a semi-transparent pellicle as in the Canon Pellix[25] and others with a small periscope such as in the Corfield Periflex series.[26]

Large-format camera

The large-format camera, taking sheet film, is a direct successor of the early plate cameras and remained in use for high-quality photography and technical, architectural, and industrial photography. There are three common types: the view camera, with its monorail and field camera variants, and the press camera. They have extensible bellows with the lens and shutter mounted on a lens plate at the front. Backs taking roll film and later digital backs are available in addition to the standard dark slide back. These cameras have a wide range of movements allowing very close control of focus and perspective. Composition and focusing are done on view cameras by viewing a ground-glass screen which is replaced by the film to make the exposure; they are suitable for static subjects only and are slow to use.

Plate camera

The earliest cameras produced in significant numbers were plate cameras, using sensitized glass plates. Light entered a lens mounted on a lens board which was separated from the plate by extendible bellows. There were simple box cameras for glass plates but also single-lens reflex cameras with interchangeable lenses and even for color photography (Autochrome Lumière). Many of these cameras had controls to raise, lower, and tilt the lens forwards or backward to control perspective.

Focusing of these plate cameras was by the use of a ground glass screen at the point of focus. Because lens design only allowed rather small aperture lenses, the image on the ground glass screen was faint and most photographers had a dark cloth to cover their heads to allow focusing and composition to be carried out more easily. When focus and composition were satisfactory, the ground glass screen was removed, and a sensitized plate was put in its place protected by a dark slide. To make the exposure, the dark slide was carefully slid out and the shutter opened, and then closed and the dark slide replaced.

Glass plates were later replaced by sheet film in a dark slide for sheet film; adapter sleeves were made to allow sheet film to be used in plate holders. In addition to the ground glass, a simple optical viewfinder was often fitted.

Medium-format camera

Medium-format cameras have a film size between the large-format cameras and smaller 35 mm cameras.[27] Typically these systems use 120 or 220 roll film.[28] The most common image sizes are 6×4.5 cm, 6×6 cm and 6×7 cm; the older 6×9 cm is rarely used. The designs of this kind of camera show greater variation than their larger brethren, ranging from monorail systems through the classic Hasselblad model with separate backs, to smaller rangefinder cameras. There are even compact amateur cameras available in this format.

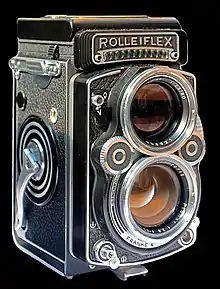

Twin-lens reflex camera

Twin-lens reflex cameras used a pair of nearly identical lenses: one to form the image and one as a viewfinder.[29] The lenses were arranged with the viewing lens immediately above the taking lens. The viewing lens projects an image onto a viewing screen which can be seen from above. Some manufacturers such as Mamiya also provided a reflex head to attach to the viewing screen to allow the camera to be held to the eye when in use. The advantage of a TLR was that it could be easily focused using the viewing screen and that under most circumstances the view seen in the viewing screen was identical to that recorded on film. At close distances, however, parallax errors were encountered, and some cameras also included an indicator to show what part of the composition would be excluded.

Some TLRs had interchangeable lenses, but as these had to be paired lenses, they were relatively heavy and did not provide the range of focal lengths that the SLR could support. Most TLRs used 120 or 220 films; some used the smaller 127 films.

Instant camera

After exposure, every photograph is taken through pinch rollers inside of the instant camera. Thereby the developer paste contained in the paper 'sandwich' is distributed on the image. After a minute, the cover sheet just needs to be removed and one gets a single original positive image with a fixed format. With some systems, it was also possible to create an instant image negative, from which then could be made copies in the photo lab. The ultimate development was the SX-70 system of Polaroid, in which a row of ten shots – engine driven – could be made without having to remove any cover sheets from the picture. There were instant cameras for a variety of formats, as well as adapters for instant film use in medium- and large-format cameras.

Subminiature camera

Subminiature cameras were first produced in the nineteenth century and use film significantly smaller than 35mm. The expensive 8×11mm Minox, the only type of camera produced by the company from 1937 to 1976, became very widely known and was often used for espionage (the Minox company later also produced larger cameras). Later inexpensive subminiatures were made for general use, some using rewound 16 mm cine film. Image quality with these small film sizes was limited.

Folding camera

The introduction of films enabled the existing designs for plate cameras to be made much smaller and for the baseplate to be hinged so that it could be folded up, compressing the bellows. These designs were very compact and small models were dubbed vest pocket cameras. Folding roll film cameras were preceded by folding plate cameras, more compact than other designs.

Box camera

Box cameras were introduced as budget-level cameras and had few, if any controls. The original box Brownie models had a small reflex viewfinder mounted on the top of the camera and had no aperture or focusing controls and just a simple shutter. Later models such as the Brownie 127 had larger direct view optical viewfinders together with a curved film path to reduce the impact of deficiencies in the lens.

Rangefinder camera

As camera lens technology developed and wide aperture lenses became more common, rangefinder cameras were introduced to make focusing more precise. Early rangefinders had two separate viewfinder windows, one of which is linked to the focusing mechanisms and moved right or left as the focusing ring is turned. The two separate images are brought together on a ground glass viewing screen. When vertical lines in the object being photographed meet exactly in the combined image, the object is in focus. A normal composition viewfinder is also provided. Later the viewfinder and rangefinder were combined. Many rangefinder cameras had interchangeable lenses, each lens requiring its range- and viewfinder linkages.

Rangefinder cameras were produced in half- and full-frame 35 mm and roll film (medium format).

Motion picture cameras

A movie camera or a video camera operates similarly to a still camera, except it records a series of static images in rapid succession, commonly at a rate of 24 frames per second. When the images are combined and displayed in order, the illusion of motion is achieved.[30]: 4

Cameras that capture many images in sequence are known as movie cameras or as cine cameras in Europe; those designed for single images are still cameras. However, these categories overlap as still cameras are often used to capture moving images in special effects work and many modern cameras can quickly switch between still and motion recording modes.

A ciné camera or movie camera takes a rapid sequence of photographs on an image sensor or strips of film. In contrast to a still camera, which captures a single snapshot at a time, the ciné camera takes a series of images, each called a frame, through the use of an intermittent mechanism.

The frames are later played back in a ciné projector at a specific speed, called the frame rate (number of frames per second). While viewing, a person's eyes and brain merge the separate pictures to create the illusion of motion. The first ciné camera was built around 1888 and by 1890 several types were being manufactured. The standard film size for ciné cameras was quickly established as 35mm film and this remained in use until the transition to digital cinematography. Other professional standard formats include 70 mm film and 16 mm film whilst amateur filmmakers used 9.5 mm film, 8 mm film, or Standard 8 and Super 8 before the move into digital format.

The size and complexity of ciné cameras vary greatly depending on the uses required of the camera. Some professional equipment is very large and too heavy to be handheld whilst some amateur cameras were designed to be very small and light for single-handed operation.

Professional video camera

A professional video camera (often called a television camera even though the use has spread beyond television) is a high-end device for creating electronic moving images (as opposed to a movie camera, that earlier recorded the images on film). Originally developed for use in television studios, they are now also used for music videos, direct-to-video movies, corporate and educational videos, marriage videos, etc.

These cameras earlier used vacuum tubes and later electronic image sensors.

Camcorders

A camcorder is an electronic device combining a video camera and a video recorder. Although marketing materials may use the colloquial term "camcorder", the name on the package and manual is often "video camera recorder". Most devices capable of recording video are camera phones and digital cameras primarily intended for still pictures; the term "camcorder" is used to describe a portable, self-contained device, with video capture and recording its primary function.

Digital camera

A digital camera (or digicam) is a camera that encodes digital images and videos and stores them for later reproduction.[31] They typically use semiconductor image sensors.[32] Most cameras sold today are digital,[33] and they are incorporated into many devices ranging from mobile phones (called camera phones) to vehicles.

Digital and film cameras share an optical system, typically using a lens of variable aperture to focus light onto an image pickup device.[34] The aperture and shutter admit the correct amount of light to the imager, just as with film but the image pickup device is electronic rather than chemical. However, unlike film cameras, digital cameras can display images on a screen immediately after being captured or recorded, and store and delete images from memory. Most digital cameras can also record moving videos with sound. Some digital cameras can crop and stitch pictures & perform other elementary image editing.

Consumers adopted digital cameras in the 1990s. Professional video cameras transitioned to digital around the 2000s–2010s. Finally, movie cameras transitioned to digital in the 2010s.

The first camera using digital electronics to capture and store images was developed by Kodak engineer Steven Sasson in 1975. He used a charge-coupled device (CCD) provided by Fairchild Semiconductor, which provided only 0.01 megapixels to capture images. Sasson combined the CCD device with movie camera parts to create a digital camera that saved black and white images onto a cassette tape.[35]: 442 The images were then read from the cassette and viewed on a TV monitor.[36]: 225 Later, cassette tapes were replaced by flash memory.

In 1986, Japanese company Nikon introduced an analog-recording electronic single-lens reflex camera, the Nikon SVC.[37]

The first full-frame digital SLR cameras were developed in Japan from around 2000 to 2002: the MZ-D by Pentax,[38] the N Digital by Contax's Japanese R6D team,[39] and the EOS-1Ds by Canon.[40] Gradually in the 2000s, the full-frame DSLR became the dominant camera type for professional photography.

On most digital cameras a display, often a liquid crystal display (LCD), permits the user to view the scene to be recorded and settings such as ISO speed, exposure, and shutter speed.[5]: 6–7 [41]: 12

Camera phone

In 2000, Sharp introduced the world's first digital camera phone, the J-SH04 J-Phone, in Japan.[42] By the mid-2000s, higher-end cell phones had an integrated digital camera, and by the beginning of the 2010s, almost all smartphones had an integrated digital camera.

See also

- Camera matrix

- History of the camera

- Camera phone

- List of camera types

- List of digital camera brands

Footnotes

- These f-stops are also referred to as f-numbers, stop numbers, or simply steps or stops. Technically the f-number is the focal length of the lens divided by the diameter of the effective aperture.

- Theoretically, they can extend to f/64 or higher.[8]

- Some photographers use handheld exposure meters independent of the camera and use the readings to manually set the exposure settings on the camera.[16]

- Film canisters typically contain a DX code that can be read by modern cameras so that the camera's computer knows the sensitivity of the film, the ISO.[9]]

- The older type of disposable flashbulb uses an aluminum or zirconium wire in a glass tube filled with oxygen. During the exposure, the wire is burned away, producing a bright flash.[16]

References

- "World's oldest photo sold to library". BBC News. 21 March 2002. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

The image of an engraving depicting a man leading a horse was made in 1825 by Nicéphore Niépce, who invented a technique known as heliogravure.

- Gustavson, Todd (2009). Camera: a history of photography from daguerreotype to digital. New York: Sterling Publishing Co., Inc. ISBN 978-1-4027-5656-6.

- "camera design | designboom.com". designboom | architecture & design magazine. Retrieved 18 September 2021.

- Young, Hugh D.; Freedman, Roger A.; Ford, A. Lewis (2008). Sears and Zemansky's University Physics (12 ed.). San Francisco, California: Pearson Addison-Wesley. ISBN 978-0-321-50147-9.

- London, Barbara; Upton, John; Kobré, Kenneth; Brill, Betsy (2002). Photography (7 ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-028271-2.

- Columbia University (2018). "camera". In Paul Lagasse (ed.). The Columbia Encyclopedia (8 ed.). Columbia University Press.

- "How Cameras Work". How Stuff Works. 21 March 2001. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Laney, Dawn A. ..BA, MS, CGC, CCRC. “Camera Technologies.” Salem Press Encyclopedia of Science, June 2020. Accessed 6 February 2022.

- Lynne Warren, ed. (2006). "Camera: An Overview". Encyclopedia of twentieth-century photography. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-57958-393-4.

- "technology of photography". Britannica Academic. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Lynne Warren, ed. (2006). "Camera: 35 mm". Encyclopedia of twentieth-century photography. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-57958-393-4.

- The British Journal Photographic Almanac. Henry Greenwood and Co. Ltd. 1956. pp. 468–471.

- Rose, B (2007). "The Camera Defined". The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography. Elsevier. pp. 770–771. doi:10.1016/B978-0-240-80740-9.50152-5. ISBN 978-0-240-80740-9. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Motion-picture camera". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "Camera". World Encyclopedia. Philip's. 2004. ISBN 978-0-19-954609-1. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- "camera". Britannica Academic. Retrieved 12 December 2019.

- McHugh, Sean. "Understanding Camera Lenses". Cambridge in Colour. Archived from the original on 19 August 2013.

- Brown, Gary (April 2000). "How Autofocus Cameras Work". HowStuffWorks.com. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013.

- Wehner, Mike (19 October 2011). "Lytro camera lets you focus after shooting, now available for pre-order". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on 22 October 2011.

- "How important is film speed?". HowStuffWorks. 7 December 2010. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- "Understanding White Balance". www.cambridgeincolour.com. Retrieved 21 September 2021.

- Roger Hicks (1984). A History of the 35 mm Still Camera. Focal Press, London & Boston. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-240-51233-4.

- Rudolph Lea (1993). Register of 35 mm SLR cameras. Wittig Books, Hückelhoven. p. 23. ISBN 978-3-88984-130-8.

- Michael R. Peres (2013), The Focal Encyclopedia of Photography, p. 779, Taylor & Francis

- "Canon Pellix Camera". Photography in Malaysia. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013.

- Parker, Bev. "Corfield Cameras – The Periflex Era". Wolverhampton Museum of Industry.

- Wildi, Ernst (2001). The medium format advantage (2nd ed.). Boston: Focal Press. ISBN 978-1-4294-8344-5. OCLC 499049825.

- The manual of photography. Elizabeth Allen, Sophie Triantaphillidou (10th ed.). Oxford: Elsevier/Focal Press. 2011. ISBN 978-0-240-52037-7. OCLC 706802878.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Burrows, Paul (13 September 2021). "The rise and fall of the TLR: why the twin-lens reflex camera is a real classic". Digital Camera World. Future US Inc. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- Ascher, Steven; Pincus, Edward (2007). The Filmmaker's Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for the Digital Age (3 ed.). New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-452-28678-8.

- Farlex Inc: definition of digital camera at the Free Dictionary; retrieved 7 September 2013

- Williams, J. B. (2017). The Electronics Revolution: Inventing the Future. Springer. pp. 245–8. ISBN 978-3-319-49088-5.

- Musgrove, Mike (12 January 2006). "Nikon Says It's Leaving Film-Camera Business". Washington Post. Retrieved 23 February 2007.

- MakeUseOf: How does a Digital Camera Work; retrieved 7 September 2013

- Gustavson, Todd (1 November 2011). 500 Cameras: 170 Years of Photographic Innovation. Toronto, Ontario: Sterling Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-1-4027-8086-8.

- Hitchcock, Susan (editor) (20 September 2011). Susan Tyler Hitchcock (ed.). National Geographic complete photography. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4351-3968-8.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - Nikon SLR-type digital cameras, Pierre Jarleton

- The long, difficult road to Pentax full-frame The long, difficult road to Pentax full-frame, Digital Photography Review

- British Journal of Photography, Issues 7410-7422, 2003, p. 2

- Canon EOS-1Ds, 11 megapixel full-frame CMOS, Digital Photography Review

- Burian, Peter; Caputo, Robert (2003). National Geographic photography field guide (2 ed.). Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-0-7922-5676-2.

- "Evolution of the Camera phone: From Sharp J-SH04 to Nokia 808 Pureview". Hoista.net. 28 February 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2013.

Further reading

- Ascher, Steven; Pincus, Edward (2007). The Filmmaker's Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide for the Digital Age (3 ed.). New York: Penguin Group. ISBN 978-0-452-28678-8.

- Frizot, Michel (January 1998). "Light machines: On the threshold of invention". In Michel Frizot (ed.). A New History of Photography. Koln, Germany: Konemann. ISBN 978-3-8290-1328-4.

- Gernsheim, Helmut (1986). A Concise History of Photography (3 ed.). Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 978-0-486-25128-8.

- Hirsch, Robert (2000). Seizing the Light: A History of Photography. New York: McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. ISBN 978-0-697-14361-7.

- Hitchcock, Susan (editor) (20 September 2011). Susan Tyler Hitchcock (ed.). National Geographic complete photography. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4351-3968-8.

{{cite book}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - Johnson, William S.; Rice, Mark; Williams, Carla (2005). Therese Mulligan; David Wooters (eds.). A History of Photography. Los Angeles, California: Taschen America. ISBN 978-3-8228-4777-0.

- Spira, S.F.; Lothrop, Easton S. Jr.; Spira, Jonathan B. (2001). The History of Photography as Seen Through the Spira Collection. New York: Aperture. ISBN 978-0-89381-953-8.

- Starl, Timm (January 1998). "A New World of Pictures: The Daguerreotype". In Michel Frizot (ed.). A New History of Photography. Koln, Germany: Konemann. ISBN 978-3-8290-1328-4.

- Wenczel, Norma (2007). "Part I – Introducing an Instrument" (PDF). In Wolfgang Lefèvre (ed.). The Optical Camera Obscura II Images and Texts. Inside the Camera Obscura – Optics and Art under the Spell of the Projected Image. Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. pp. 13–30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2012.