Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor

Charles V[lower-alpha 2][lower-alpha 3] (24 February 1500 – 21 September 1558) was Holy Roman Emperor and Archduke of Austria from 1519 to 1556, King of Spain (Castile and Aragon) from 1516 to 1556, and Lord of the Netherlands as titular Duke of Burgundy from 1506 to 1555. As he was head of the rising House of Habsburg during the first half of the 16th century, his dominions in Europe included the Holy Roman Empire, extending from Germany to northern Italy with direct rule over the Austrian hereditary lands and the Burgundian Low Countries, and the Kingdom of Spain with its southern Italian possessions of Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia. Furthermore, he oversaw both the continuation of the long-lasting Spanish colonization of the Americas and the short-lived German colonization of the Americas. The personal union of the European and American territories of Charles V was the first collection of realms labelled "the empire on which the sun never sets".[9]

| Charles V | |

|---|---|

Portrait by Titian, probably with Lambert Sustris, 1548 | |

| |

| Reign | 28 June 1519 – 27 August 1556[lower-alpha 1] |

| Coronation | |

| Predecessor | Maximilian I |

| Successor | Ferdinand I |

| King of Spain (Castile and Aragon) as Charles I | |

| Reign | 14 March 1516 – 16 January 1556 |

| Predecessor | Joanna |

| Successor | Philip II |

| Co-monarch | Joanna (until 1555) |

| Archduke of Austria as Charles I | |

| Reign | 12 January 1519 – 21 April 1521 |

| Predecessor | Maximilian I |

| Successor | Ferdinand I (in the name of Charles V until 1556) |

| |

| Reign | 25 September 1506 – 25 October 1555 |

| Predecessor | Philip I of Castile |

| Successor | Philip II of Spain |

| Governor | See list

|

| Regent | Margaret of Austria (1506-1515) |

| Born | 24 February 1500 Prinsenhof of Ghent, Flanders, Burgundian Low Countries |

| Died | 21 September 1558 (aged 58) Monastery of Yuste, Crown of Castile |

| Burial | 22 September 1558 El Escorial, Spain |

| Spouse | Isabella of Portugal

(m. 1526; died 1539) |

| Issue among others |

|

| House | Habsburg |

| Father | Philip I, King of Castile |

| Mother | Joanna, Queen of Castile and Aragon |

| Religion | Catholicism |

| Signature |  |

Charles was born in the County of Flanders to Philip of Habsburg (son of Maximilian I of Habsburg and Mary of Burgundy) and Joanna of Trastámara (daughter of Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain). The ultimate heir of his four grandparents, Charles inherited all of his family dominions at a young age. After the death of Philip in 1506, he inherited the Burgundian states originally held by his paternal grandmother Mary.[10] In 1516, inheriting the dynastic union formed by his maternal grandparents Isabella I and Ferdinand II, he became king of Spain as co-monarch of the Spanish kingdoms with his mother. Spain's possessions at his accession also included the Castilian colonies of the West Indies and the Spanish Main as well as the Aragonese kingdoms of Naples, Sicily and Sardinia. At the death of his paternal grandfather Maximilian in 1519, he inherited Austria and was elected to succeed him as Holy Roman Emperor. He adopted the Imperial name of Charles V as his main title, and styled himself as a new Charlemagne.[11]

Charles V revitalized the medieval concept of universal monarchy and spent most of his life attempting to defend the integrity of the Holy Roman Empire from the Protestant Reformation, the expansion of the Ottoman Empire, and a series of wars with France.[12][13] With no fixed capital city, he made 40 journeys, travelling from country to country; he spent a quarter of his reign on the road.[14] The imperial wars were fought by German Landsknechte, Spanish tercios, Burgundian knights, and Italian condottieri. Charles V borrowed money from German and Italian bankers and, in order to repay such loans, he relied on the proto-capitalist economy of the Low Countries and on the flows of gold and especially silver from South America to Spain, which caused widespread inflation. He ratified the Spanish conquest of the Aztec and Inca empires by the Spanish conquistadores Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro, as well as the establishment of Klein-Venedig by the German Welser family in search of the legendary El Dorado. In order to consolidate power in his early reign, Charles overcame two Spanish insurrections (the Comuneros' Revolt and Brotherhoods' Revolt) and two German rebellions (the Knights' Revolt and Great Peasants' Revolt).

Crowned King in Germany, Charles sided with Pope Leo X and declared Martin Luther an outlaw at the Diet of Worms (1521).[15] The same year, Francis I of France, surrounded by the Habsburg possessions, started a conflict in Lombardy that lasted until the Battle of Pavia (1525), which led to the French king's temporary imprisonment. The Protestant affair re-emerged in 1527 as Rome was sacked by an army of Charles's mutinous soldiers, largely of Lutheran faith. In the following years, Charles V defended Vienna from the Turks and obtained a coronation as King of Italy and Holy Roman Emperor from Pope Clement VII. In 1535, he annexed the vacant Duchy of Milan and captured Tunis. Nevertheless, the loss of Buda during the struggle for Hungary and the Algiers expedition in the early 1540s frustrated his anti-Ottoman policies. Meanwhile, Charles V had come to an agreement with Pope Paul III for the organisation of the Council of Trent (1545). The refusal of the Lutheran Schmalkaldic League to recognize the council's validity led to a war, won by Charles V with the imprisonment of the Protestant princes. However, Henry II of France offered new support to the Lutheran cause and strengthened a close alliance with the sultan Suleiman the Magnificent, the ruler of the Ottoman Empire since 1520.

Ultimately, Charles V conceded the Peace of Augsburg and abandoned his multi-national project with a series of abdications in 1556 that divided his hereditary and imperial domains between the Spanish Habsburgs headed by his son Philip II of Spain and the Austrian Habsburgs headed by his brother Ferdinand, who had been archduke of Austria in Charles's name since 1521 and the designated successor as emperor since 1531.[16][17][18] The Duchy of Milan and the Habsburg Netherlands were also left in personal union to the king of Spain, although initially also belonging to the Holy Roman Empire. The two Habsburg dynasties remained allied until the extinction of the Spanish line in 1700. In 1557, Charles retired to the Monastery of Yuste in Extremadura and died there a year later.

Heritage and early life

Childhood

| Ancestors of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Charles of Habsburg was born on 24 February 1500 in the Prinsenhof of Ghent, a Flemish city of the Burgundian Low Countries, to Philip of Habsburg and Joanna of Trastámara.[19] His father Philip, nicknamed Philip the Handsome, was the firstborn son of Maximilian I of Habsburg, Archduke of Austria as well as Holy Roman Emperor, and Mary the Rich, Burgundian duchess of the Low Countries. His mother Joanna, known as Joanna the Mad for the mental disorders said to afflict her, was a daughter of Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, the Catholic Monarchs of Spain from the House of Trastámara. The political marriage of Philip and Joanna was first conceived in a letter sent by Maximilian to Ferdinand in order to seal an Austro-Spanish alliance, established as part of the League of Venice directed against the Kingdom of France during the Italian Wars.[20]

From the moment he became King of the Romans (de facto Crown Prince of the Holy Roman Empire) in 1486, Charles's paternal grandfather Maximilian had carried a very financially risky policy of maximum expansionism, relying mostly on the resources of the Austrian hereditary lands.[21] Even though it is often implied (among others, by Erasmus of Rotterdam[22]) that Charles V and the Habsburgs gained their vast empire through peaceful policies (exemplified by the saying Bella gerant aliī, tū fēlix Austria nūbe/ Nam quae Mars aliīs, dat tibi regna Venus or "Let others wage war, but thou, O happy Austria, marry; for those kingdoms which Mars gives to others, Venus gives to thee.", reportedly spoken by Mathias Corvinus[23][24]), Maximilian and his descendants fought wars aplenty (Maximilian alone fought 27 wars during his four decades of ruling).[25][26] His general strategy was to combine his intricate systems of alliance, wars, military threats and offers of marriage to realize his expansionist ambitions. Ultimately he succeeded in coercing Bohemia, Hungary and Poland into acquiescence in the Habsburgs' expansionist plan.[26][27][28]

The fact that the marriages between the Habsburgs and the Trastámaras, originally conceived as a marital alliance against France, would bring the crowns of Castille and Aragon to Maximilian's male line, however, was unexpected.[29][30]

The marriage contract between Philip and Joanna was signed in 1495, and celebrations were held in 1496. Philip was already Duke of Burgundy, given Mary's death in 1482, and also heir apparent of Austria as honorific Archduke. Joanna, in contrast, was only third in the Spanish line of succession, preceded by her older brother John of Castile and older sister Isabella of Aragon. Although both John and Isabella died in 1498, the Catholic Monarchs desired to keep the Spanish kingdoms in Iberian hands and designated their Portuguese grandson Miguel da Paz as heir presumptive of Spain by naming him Prince of the Asturias.[31]

Charles was born in a bathroom of the Prinsenhof at 3:00 AM by Joanna not long after she attended a ball despite symptoms of labor pains, and his name was chosen by Philip in honour of Charles I of Burgundy. According to a poet at the court, the people of Ghent "shouted Austria and Burgundy throughout the whole city for three hours" to celebrate his birth.[20] Given the dynastic situation, the newborn was originally heir apparent only of the Burgundian Low Countries as the honorific Duke of Luxembourg and became known in his early years simply as Charles of Ghent. He was baptized at the Church of Saint John by the Bishop of Tournai: Charles I de Croÿ and John III of Glymes were his godfathers; Margaret of York and Margaret of Austria his godmothers. Charles's baptism gifts were a sword and a helmet, objects of Burgundian chivalric tradition representing, respectively, the instrument of war and the symbol of peace.[32]

In 1501, Philip and Joanna left Charles to the custody of Margaret of York and went to Spain. The main goal of their Spanish mission was the recognition of Joanna as Princess of Asturias, given prince Miguel's death a year earlier. They succeeded despite facing some opposition from the Spanish Cortes, reluctant to create the premises for Habsburg succession. In 1504, as Isabella died, Joanna became Queen of Castile.[33] Charles only met his father again in 1503 while his mother returned in 1504 (after giving birth to Ferdinand in Spain). The Spanish Ambassador Fuensalida reported that Philip often visited and they had lots of fun. The couple's unhappy marriage and Joanna's unstable mental state however created many difficulties, making it unsafe for the children to stay with the parents.[34] Philip was recognized King in 1506. He died shortly after, an event that drove the mentally unstable Joanna into complete insanity. She retired in isolation into a tower of Tordesillas. Ferdinand took control of all the Spanish kingdoms, under the pretext of protecting Charles's rights, which in reality he wanted to elude, but his new marriage with Germaine de Foix failed to produce a surviving Trastámara heir to the throne. With his father dead and his mother confined, Charles became Duke of Burgundy and was recognized as prince of Asturias (heir presumptive of Spain) and honorific archduke (heir apparent of Austria).[35]

Inheritances

The Burgundian inheritance included the Habsburg Netherlands, which consisted of a large number of the lordships that formed the Low Countries and covered modern-day Belgium, Netherlands and Luxembourg. It excluded Burgundy proper, annexed by France in 1477, with the exception of Franche-Comté. At the death of Philip in 1506, Charles was recognized Lord of the Netherlands with the title of Charles II of Burgundy. During his childhood and teen years, Charles lived in Mechelen together with his sisters Mary, Eleanor, and Isabella at the court of his aunt Margaret of Austria, Duchess of Savoy. William de Croÿ (later prime minister) and Adrian of Utrecht (later Pope Adrian VI) served as his tutors. The culture and courtly life of the Low Countries played an important part in the development of Charles's beliefs. As a member of the Burgundian Order of the Golden Fleece in his infancy, and later its grandmaster, Charles was educated to the ideals of the medieval knights and the desire for Christian unity to fight the infidel.[36] The Low Countries were very rich during his reign, both economically and culturally. Charles was very attached to his homeland and spent much of his life in Brussels and various Flemish cities.

The Spanish inheritance, resulting from a dynastic union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon, included Spain as well as the Castilian possessions in the Americas (the Spanish West Indies and the Province of Tierra Firme) and the Aragonese kingdoms of Naples, Sicily, and Sardinia. Joanna inherited these territories in 1516 in a condition of mental illness. Charles, therefore, claimed the crowns for himself jure matris, thus becoming co-monarch of Joanna with the title of Charles I of Castile and Aragon or Charles I of Spain. Castile and Aragon together formed the largest of Charles's personal possessions, and they also provided a great number of generals and tercios (the formidable Spanish infantry of the time), while Joanna remained confined in Tordesillas until her death. However, at his accession to the throne, Charles was viewed as a foreign prince.[37]

Two rebellions, the revolt of the Germanies and the revolt of the comuneros, contested Charles's rule in the 1520s. Following these revolts, Charles placed Spanish counselors in a position of power and spent a considerable part of his life in Castile, including his final years in a monastery. Indeed, Charles's motto "Plus Oultre" (Further Beyond), rendered as Plus Ultra from the original French, became the national motto of Spain and his heir, later Philip II, was born and raised in Castile. Nonetheless, many Spaniards believed that their resources (largely consisting of flows of silver from the Americas) were being used to sustain Imperial-Habsburg policies that were not in the country's interest.[37]

Charles inherited the Austrian hereditary lands in 1519, as Charles I of Austria, and obtained the election as Holy Roman Emperor against the candidacy of the French King. Since the Imperial election, he was known as Emperor Charles V even outside of Germany and the Habsburg motto A.E.I.O.U. ("Austria Est Imperare Orbi Universo"; "it is Austria's destiny to rule the world") acquired political significance. Despite the fact that he was elected as a German prince, Charles's staunch Catholicism in contrast to the growth of Lutheranism alienated him from various German princes who finally fought against him. Charles's presence in Germany was often marked by the organization of imperial diets to maintain religious and political unity.[38][39]

He was frequently in Northern Italy, often taking part in complicated negotiations with the Popes to address the rise of Protestantism. It is important to note, though, that the German Catholics supported the Emperor. Charles had a close relationship with important German families, like the House of Nassau, many of which were represented at his Imperial court. Several German princes or noblemen accompanied him in his military campaigns against France or the Ottomans, and the bulk of his army was generally composed of German troops, especially the Imperial Landsknechte.[38][39]

It is said that Charles spoke several languages. He was fluent in French and Dutch, his native languages. He later added an acceptable Castilian Spanish, which he was required to learn by the Castilian Cortes Generales. He could also speak some Basque, acquired by the influence of the Basque secretaries serving in the royal court.[40] He gained a decent command of German following the Imperial election, though he never spoke it as well as French.[41] By 1532, Charles was proficient in Portuguese, to the amazement of diplomats.[42] A witticism sometimes attributed to Charles is: "I speak Spanish/Latin (depending on the source) to God, Italian to women, French to men and German to my horse."[43] A variant of the quote is attributed to him by Swift in his 1726 Gulliver's Travels, but there are no contemporary accounts referencing the quotation (which has many other variants) and it is often attributed instead to Frederick the Great.[44][45]

Reign

Given the vast dominions of the House of Habsburg, Charles was often on the road and needed deputies to govern his realms for the times he was absent from his territories. His first Governor of the Netherlands was Margaret of Austria (succeeded by Mary of Hungary and Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy). His first Regent of Spain was Adrian of Utrecht (succeeded by Isabella of Portugal and Philip II of Spain). For the regency and governorship of the Austrian hereditary lands, Charles named his brother Ferdinand Archduke in the Austrian lands under his authority at the Diet of Worms (1521). Charles also agreed to favor the election of Ferdinand as King of the Romans in Germany, which took place in 1531. By virtue of these agreements Ferdinand became Holy Roman Emperor and obtained hereditary rights over Austria at the abdication of Charles in 1556.[16][46] Charles de Lannoy, Carafa and Antonio Folc de Cardona y Enriquez were the viceroys of the kingdoms of Naples, Sicily and Sardinia, respectively.

Charles V travelled ten times to the Low Countries, nine to Germany,[47] seven to Spain,[48] seven to Italy,[49] four to France, two to England, and two to North Africa.[50] During all his travels, the Emperor left a documentary trail in almost every place he went, allowing historians to surmise that he spent 10,000 days in the Low Countries, 6,500 days in Spain, 3,000 days in Germany, and 1,000 days in Italy. He further spent 195 days in France, 99 in North Africa and 44 days in England. For only 260 days his exact location is unrecorded, all of them being days spent at sea travelling between his dominions.[51] As he put it in his last public speech: "my life has been one long journey".[52]

Burgundy and the Low Countries

In 1506, Charles inherited his father's Burgundian territories that included Franche-Comté and, most notably, the Low Countries. The latter territories lay within the Holy Roman Empire and its borders, but were formally divided between fiefs of the German kingdom and French fiefs such as Charles's birthplace of Flanders, a last remnant of what had been a powerful player in the Hundred Years' War. As he was a minor, his aunt Margaret of Austria (born as Archduchess of Austria and in both her marriages as the Dowager Princess of Asturias and Dowager Duchess of Savoy) acted as regent, as appointed by Emperor Maximilian until 1515. She soon found herself at war with France over Charles's requirement to pay homage to the French king for Flanders, as his father had done. The outcome was that France relinquished its ancient claim on Flanders in 1528.

From 1515 to 1523, Charles's government in the Netherlands also had to contend with the rebellion of Frisian peasants (led by Pier Gerlofs Donia and Wijard Jelckama). The rebels were initially successful but after a series of defeats, the remaining leaders were captured and decapitated in 1523.

Charles extended the Burgundian territory with the annexation of Tournai, Artois, Utrecht, Groningen, and Guelders. The Seventeen Provinces had been unified by Charles's Burgundian ancestors, but nominally were fiefs of either France or the Holy Roman Empire. Charles eventually won the Guelders Wars and united all provinces under his rule, the last one being the Duchy of Guelders. In 1549, Charles issued a Pragmatic Sanction, declaring the Low Countries to be a unified entity of which his family would be the heirs.[55]

The Low Countries held an essential place in the Empire. For Charles V, they were his home, the region where he was born and spent his childhood. Because of trade and industry and the wealth of the region's cities, the Low Countries also represented a significant income for the Imperial treasury.

The Burgundian territories were generally loyal to Charles throughout his reign. The important city of Ghent rebelled in 1539 due to heavy tax payments demanded by Charles. The rebellion did not last long, however, as Charles's military response, with reinforcement from the Duke of Alba,[55] was swift and humiliating to the rebels of Ghent.[56][57]

Spanish Kingdoms

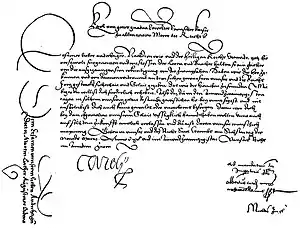

In the Castilian Cortes of Valladolid in 1506 and of Madrid in 1510, Charles was sworn as the Prince of Asturias, heir-apparent to his mother the Queen Joanna.[60] On the other hand, in 1502, the Aragonese Corts gathered in Saragossa and pledged an oath to Joanna as heiress-presumptive, but the Archbishop of Saragossa expressed firmly that this oath could not establish jurisprudence, that is to say, modify the right of the succession, except by virtue of a formal agreement between the Cortes and the King.[61][62] So, upon the death of King Ferdinand II of Aragon, on 23 January 1516, Joanna inherited the Crown of Aragon, which consisted of Aragon, Catalonia, Valencia, Naples, Sicily and Sardinia, while Charles became governor general.[63] Nevertheless, the Flemings wished Charles to assume the royal title, and this was supported by Emperor Maximilian I and Pope Leo X.

Thus, after the celebration of Ferdinand II's obsequies on 14 March 1516, Charles was proclaimed king of the crowns of Castile and Aragon jointly with his mother. Finally, when the Castilian regent Cardinal Jiménez de Cisneros accepted the fait accompli, he acceded to Charles's desire to be proclaimed king and imposed his enstatement throughout the kingdom.[64] Charles arrived in his new kingdoms in autumn of 1517. Jiménez de Cisneros came to meet him but fell ill along the way, not without a suspicion of poison, and he died before reaching the King.[65]

Due to the irregularity of Charles assuming the royal title while his mother, the legitimate queen, was alive, the negotiations with the Castilian Cortes in Valladolid (1518) proved difficult.[66] In the end Charles was accepted under the following conditions: he would learn to speak Castilian; he would not appoint foreigners; he was prohibited from taking precious metals from Castile beyond the Quinto Real; and he would respect the rights of his mother, Queen Joanna. The Cortes paid homage to him in Valladolid in February 1518. After this, Charles departed to the crown of Aragon.[67]

He managed to overcome the resistance of the Aragonese Cortes and Catalan Corts,[68] and he was recognized as king of Aragon and count of Barcelona jointly with his mother, while his mother was kept confined and could only rule in name.[69] The Kingdom of Navarre had been invaded by Ferdinand of Aragon jointly with Castile in 1512, but he pledged a formal oath to respect the kingdom. On Charles's accession to the Spanish thrones, the Parliament of Navarre (Cortes) required him to attend the coronation ceremony (to become Charles IV of Navarre). Still, this demand fell on deaf ears, and the Parliament kept piling up grievances.

Charles was accepted as sovereign, even though the Spanish felt uneasy with the Imperial style. Spanish kingdoms varied in their traditions. Castile had become an authoritarian, highly centralized kingdom, where the monarchs own will easily overrode legislative and justice institutions.[70] By contrast, in the crown of Aragon, and especially in the Pyrenean kingdom of Navarre, law prevailed, and the monarchy was seen as a contract with the people.[71] This became an inconvenience and a matter of dispute for Charles V and later kings since realm-specific traditions limited their absolute power. With Charles, the government became more absolute, even though until his mother died in 1555, Charles did not hold the full kingship of the country.

Soon resistance to the Emperor arose because of heavy taxation to support foreign wars in which Castilians had little interest and because Charles tended to select Flemings for high offices in Castile and America, ignoring Castilian candidates. The resistance culminated in the Revolt of the Comuneros, which Charles suppressed. Comuneros once released Joanna and wanted to depose Charles and support Joanna to be the sole monarch instead. While Joanna refused to depose her son, her confinement would continue after the revolt to prevent possible events alike. Immediately after crushing the Castilian revolt, Charles was confronted again with the hot issue of Navarre when King Henry II attempted to reconquer the kingdom. Main military operations lasted until 1524, when Hondarribia surrendered to Charles's forces, but frequent cross-border clashes in the western Pyrenees only stopped in 1528 (Treaties of Madrid and Cambrai).

After these events, Navarre remained a matter of domestic and international litigation still for a century (a French dynastic claim to the throne did not end until the July Revolution in 1830). Charles wanted his son and heir Philip II to marry the heiress of Navarre, Jeanne d'Albret. Jeanne was instead forced to marry William, Duke of Julich-Cleves-Berg, but that childless marriage was annulled after four years. She next married Antoine de Bourbon, and both she and their son would oppose Philip II in the French Wars of Religion.

After its integration into Charles's empire, Castile guaranteed effective military units and its American possessions provided the bulk of the empire's financial resources. However, the two conflicting strategies of Charles V, enhancing the possessions of his family and protecting Catholicism against Protestants heretics, diverted resources away from building up the Spanish economy. Elite elements in Spain called for more protection for the commercial networks, which were threatened by the Ottoman Empire. Charles instead focused on defeating Protestantism in Germany and the Netherlands, which proved to be lost causes. Each hastened the economic decline of the Spanish Empire in the next generation.[72] The enormous budget deficit accumulated during Charles's reign, along with the inflation that affected the kingdom, resulted in declaring bankruptcy during the reign of Philip II.[73]

Italian states

.jpg.webp)

The Crown of Aragon inherited by Charles included the Kingdom of Naples, the Kingdom of Sicily and the Kingdom of Sardinia. As Holy Roman Emperor, Charles was sovereign in several states of northern Italy and had a claim to the Iron Crown of Lombardy (obtained in 1530). The Duchy of Milan, however, was under French control. France took Milan from the House of Sforza after victory against Switzerland at the Battle of Marignano in 1515.

Imperial-Papal troops succeeded in re-installing the Sforza in Milan in 1521, in the context of an alliance between Charles V and Pope Leo X. A Franco-Swiss army was expelled from Lombardy at the Battle of Bicocca 1522. In 1524, Francis I of France retook the initiative, crossing into Lombardy where Milan, along with several other cities, once again fell to his attack. Pavia alone held out, and on 24 February 1525 (Charles's twenty-fifth birthday), Charles's forces led by Charles de Lannoy captured Francis and crushed his army in the Battle of Pavia.

In 1535 Francesco II Sforza died without heirs, and Charles V annexed the territory as a vacant Imperial state with the help of Massimiliano Stampa, one of the most influential courtiers of the late Duke.[74] Charles successfully held on to all of its Italian territories, though they were invaded again on multiple occasions during the Italian Wars.

In addition, Habsburg trade in the Mediterranean was consistently disrupted by the Ottoman Empire. In 1538 a Holy League consisting of all the Italian states and the Spanish kingdoms was formed to drive the Ottomans back, but it was defeated at the Battle of Preveza. Decisive naval victory eluded Charles; it would not be achieved until after his death, at the Battle of Lepanto in 1571.

The Americas

During Charles's reign, the Castilian territories in the Americas were considerably extended by conquistadores like Hernán Cortés and Francisco Pizarro. They conquered the large Aztec and Inca empires and incorporated them into the Empire as the Viceroyalties of New Spain and Peru between 1519 and 1542. Combined with the circumnavigation of the globe by the Magellan expedition in 1522, these successes convinced Charles of his divine mission to become the leader of Christendom, which still perceived a significant threat from Islam.[75]

The conquests also helped solidify Charles's rule by providing the state treasury with enormous amounts of bullion. As the conquistador Bernal Díaz del Castillo observed, "We came to serve God and his Majesty, to give light to those in darkness, and also to acquire that wealth which most men covet."[75] Charles used the Spanish feudal system as a model for labor relations in the new colonies. The local Spaniards strongly objected because it assumed the equality of Indians and Spaniards. The locals wanted complete control over labor and got it under Philip II in the 1570s.[76]

On 28 August 1518, Charles issued a charter authorizing the transportation of slaves direct from Africa to the Americas. Up until that point (since at least 1510), African slaves had usually been transported to Castile or Portugal and had then been transhipped to the Caribbean. Charles's decision to create a direct, more economically viable Africa to America slave trade fundamentally changed the nature and scale of the transatlantic slave trade.[77]

In 1528 Charles assigned a concession in Venezuela Province to Bartholomeus V. Welser, in compensation for his inability to repay debts owed. The concession, known as Klein-Venedig (little Venice), was revoked in 1546. In 1550, Charles convened a conference at Valladolid in order to consider the morality of the force used against the indigenous populations of the New World, which included figures such as Bartolomé de las Casas.[78]

Charles V is credited with the first idea of constructing an American Isthmus canal in Panama as early as 1520.[79]

Holy Roman Empire

After the death of his paternal grandfather, Maximilian, in 1519, Charles inherited the Habsburg monarchy. He was also the natural candidate of the electors to succeed his grandfather as Holy Roman Emperor. He defeated the candidacies of Frederick III of Saxony, Francis I of France, and Henry VIII of England. According to some, Charles became emperor due to the fact that by paying huge bribes to the electors, he was the highest bidder. He won the crown on 28 June 1519. On 23 October 1520, he was crowned in Germany and some ten years later, on 24 February 1530, he was crowned Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Clement VII in Bologna, the last emperor to receive a papal coronation.[8][80][81] Others point out that while the electors were paid, this was not the reason for the outcome, or at most played only a small part.[82] The important factor that swayed the final decision was that Frederick refused the offer, and made a speech in support of Charles on the ground that they needed a strong leader against the Ottomans, Charles had the resources and was a prince of German extraction.[83][84][85][86]

Although even at the beginning of his reign, his position was more powerful than that of any of his predecessors, the decentralized structure of the Empire proved resilient, not least because of the Reformation and the emergence in 1525 of the Common Man. It was exactly during this crucial period, Charles V and Ferdinand were too busy with non-German affairs to prevent Imperial Cities in Upper Germany from becoming estranged from imperial power.[87]

Due to Charles V's difficulties in coordinating between the Austrian, Hungarian fronts and his Mediterranean fronts in the face of the Ottoman threat, as well as in his German, Burgundian and Italian theatres of war against German Protestant Princes and France, the defense of central Europe, as well as many responsibilities involving the management of the Empire, was subcontracted to Ferdinand. Charles V abdicated as archduke of Austria in 1522, and nine years after that he had the German princes elect Ferdinand as King of the Romans, who thus became his designated successor, a move that "had profound implications for state formation in south-eastern Europe". Afterwards, Ferdinand managed to gain control of Bohemia, Silesia, Croatia and Hungary, with support from local nobles and his German vassals.[88][89][90]

Charles abdicated as emperor in 1556 in favour of his brother Ferdinand; however, due to lengthy debate and bureaucratic procedure, the Imperial Diet did not accept the abdication (and thus make it legally valid) until 24 February 1558. Up to that date, Charles continued to use the title of emperor.

Wars with France

Much of Charles's reign was taken up by conflicts with France, which found itself encircled by Charles's empire while it still maintained ambitions in Italy. In 1520, Charles visited England, where his aunt, Catherine of Aragon, urged her husband, Henry VIII, to ally himself with the emperor. In 1508 Charles was nominated by Henry VII to the Order of the Garter.[91] His Garter stall plate survives in Saint George's Chapel.

The first war with Charles's great nemesis Francis I of France began in 1521. Charles allied with England and Pope Leo X against the French and the Venetians, and was highly successful, driving the French out of Milan and defeating and capturing Francis at the Battle of Pavia in 1525.[92] To gain his freedom, Francis ceded Burgundy to Charles in the Treaty of Madrid, as well as renouncing his support of Henry II's claim over Navarre.

When he was released, however, Francis had the Parliament of Paris denounce the treaty because it had been signed under duress. France then joined the League of Cognac that Pope Clement VII had formed with Henry VIII of England, the Venetians, the Florentines, and the Milanese to resist imperial domination of Italy. In the ensuing war, Charles's sack of Rome (1527) and virtual imprisonment of Pope Clement VII in 1527 prevented the Pope from annulling the marriage of Henry VIII of England and Charles's aunt Catherine of Aragon, so Henry eventually broke with Rome, thus leading to the English Reformation.[93][94] In other respects, the war was inconclusive. In the Treaty of Cambrai (1529), called the "Ladies' Peace" because it was negotiated between Charles's aunt and Francis' mother, Francis renounced his claims in Italy but retained control of Burgundy.

A third war erupted in 1536. Following the death of the last Sforza Duke of Milan, Charles installed his son Philip in the duchy, despite Francis' claims on it. This war too was inconclusive. Francis failed to conquer Milan, but he succeeded in conquering most of the lands of Charles's ally, the Duke of Savoy, including his capital Turin. A truce at Nice in 1538 on the basis of uti possidetis ended the war but lasted only a short time. War resumed in 1542, with Francis now allied with Ottoman Sultan Suleiman I and Charles once again allied with Henry VIII. Despite the conquest of Nice by a Franco-Ottoman fleet, the French could not advance toward Milan, while a joint Anglo-Imperial invasion of northern France, led by Charles himself, won some successes but was ultimately abandoned, leading to another peace and restoration of the status quo ante bellum in 1544.

A final war erupted with Francis' son and successor, Henry II, in 1551. Henry won early success in Lorraine, where he captured Metz, but French offensives in Italy failed. Charles abdicated midway through this conflict, leaving further conduct of the war to his son, Philip II, and his brother, Ferdinand I, Holy Roman Emperor.

Conflicts with the Ottoman Empire

Charles fought continually with the Ottoman Empire and its sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent. The defeat of Hungary at the Battle of Mohács in 1526 "sent a wave of terror over Europe."[95][96] The Muslim advance in Central Europe was halted at the Siege of Vienna in 1529, followed by a counter-attack of Charles V across the Danube river. However, by 1541, central and southern Hungary fell under Turkish control.

Suleiman won the contest for mastery of the Mediterranean, in spite of Christian victories such as the conquest of Tunis in 1535.[97] The regular Ottoman fleet came to dominate the Eastern Mediterranean after its victories at Preveza in 1538 and Djerba in 1560 (shortly after Charles's death), which severely decimated the Spanish marine arm. At the same time, the Muslim Barbary corsairs, acting under the general authority and supervision of the sultan, regularly devastated the Spanish and Italian coasts and crippled Spanish trade. The advance of the Ottomans in the Mediterranean and central Europe chipped at the foundations of Habsburg power and diminished Imperial prestige.

In 1536 Francis I allied France with Suleiman against Charles. While Francis was persuaded to sign a peace treaty in 1538, he again allied himself with the Ottomans in 1542 in a Franco-Ottoman alliance. In 1543 Charles allied himself with Henry VIII and forced Francis to sign the Truce of Crépy-en-Laonnois. Later, in 1547, Charles signed a humiliating[98] treaty with the Ottomans to gain himself some respite from the huge expenses of their war.[99]

Charles V made overtures to the Safavid Empire to open a second front against the Ottomans, in an attempt at creating a Habsburg-Persian alliance. Contacts were positive, but rendered difficult by enormous distances. In effect, however, the Safavids did enter in conflict with the Ottoman Empire in the Ottoman-Safavid War, forcing it to split its military resources.[100]

Protestant Reformation

The issue of the Protestant Reformation was first brought to the imperial attention under Charles V. As Holy Roman Emperor, Charles called Martin Luther to the Diet of Worms in 1521, promising him safe conduct if he would appear. After Luther defended the Ninety-five Theses and his writings, the Emperor commented: "that monk will never make me a heretic". Charles V relied on religious unity to govern his various realms, otherwise unified only in his person, and perceived Luther's teachings as a disruptive form of heresy. He outlawed Luther and issued the Edict of Worms, declaring:

You know that I am a descendant of the Most Christian Emperors of the great German people, of the Catholic Kings of Spain, of the Archdukes of Austria, and of the Dukes of Burgundy. All of these, their whole life long, were faithful sons of the Roman Church ... After their deaths they left, by natural law and heritage, these holy catholic rites, for us to live and die by, following their example. And so until now I have lived as a true follower of these our ancestors. I am therefore resolved to maintain everything which these my forebears have established to the present.

.jpg.webp)

Nonetheless, Charles V kept his word and left Martin Luther free to leave the city. Frederick the Wise, elector of Saxony and protector of Luther, lamented the outcome of the Diet. On the road back from Worms, Luther was kidnapped by Frederick's men and hidden in a distant castle in Wartburg. There, he began to work on his German translation of the bible. The spread of Lutheranism led to two major revolts: that of the knights in 1522–1523 and that of the peasants led by Thomas Muntzer in 1524–1525. While the pro-Imperial Swabian League, in conjunction with Protestant princes afraid of social revolts, restored order, Charles V used the instrument of pardon to maintain peace.

Thereafter, Charles V took a tolerant approach and pursued a policy of reconciliation with the Lutherans. At the 1530 Imperial Diet of Augsburg was requested by Emperor Charles V to decide on three issues: first, the defence of the Empire against the Ottoman threat; second, issues related to policy, currency and public well-being; and, third, disagreements about Christianity, in attempt to reach some compromise and a chance to deal with the German situation.[102] The Diet was inaugurated by the emperor on 20 June. It produced numerous outcomes, most notably the 1530 declaration of the Lutheran estates known as the Augsburg Confession (Confessio Augustana), a central document of Lutheranism. Luther's assistant Philip Melanchthon went even further and presented it to Charles V. The emperor strongly rejected it, and in 1531 the Schmalkaldic League was formed by Protestant princes. In 1532, Charles V recognized the League and effectively suspended the Edict of Worms with the standstill of Nuremberg. The standstill required the Protestants to continue to take part in the Imperial wars against the Turks and the French, and postponed religious affairs until an ecumenical council of the Catholic Church was called by the Pope to solve the issue.

Due to Papal delays in organizing a general council, Charles V decided to organize a German summit and presided over the Regensburg talks between Catholics and Lutherans in 1541, but no compromise was achieved. In 1545, the Council of Trent was finally opened and the Counter-Reformation began. The Catholic initiative was supported by a number of the princes of the Holy Roman Empire. However, the Schmalkaldic League refused to recognize the validity of the council and occupied territories of Catholic princes.[103] Therefore, Charles V outlawed the Schmalkaldic League and opened hostilities against it in 1546.[104] The next year his forces drove the League's troops out of southern Germany, and defeated John Frederick, Elector of Saxony, and Philip of Hesse at the Battle of Mühlberg, capturing both. At the Augsburg Interim in 1548, he created a solution giving certain allowances to Protestants until the Council of Trent would restore unity. However, members of both sides resented the Interim and some actively opposed it.

The council was re-opened in 1550 with the participation of Lutherans, and Charles V set up the Imperial court in Innsbruck, Austria, sufficiently close to Trent for him to follow the evolution of the debates. In 1552 Protestant princes, in alliance with Henry II of France, rebelled again and the second Schmalkaldic War began. Maurice of Saxony, instrumental for the Imperial victory in the first conflict, switched side to the Protestant cause and bypassed the Imperial army by marching directly into Innsbruck with the goal of capturing the Emperor. Charles V was forced to flee the city during an attack of gout and barely made it alive to Villach in a state of semi-consciousness carried in a litter. After failing to recapture Metz from the French, Charles V returned to the Low Countries for the last years of his emperorship. In 1555, he instructed his brother Ferdinand to sign the Peace of Augsburg in his name. The agreements led to the religious division of Germany between Catholic and Protestant princedoms.[105]

Finance

Charles's main sources of revenue were from Castile, Naples and the Low Countries, which yielded in total an annual amount of around 2.8 million Spanish ducats in the 1520s and about 4.8 million Spanish ducats in the 1540s. Ferdinand I's annual revenue totalled between 1.7 million and 1.9 million Venetian ducats (2.15–2.5 million florin or Rhine gulden). Their chief enemy, the Ottomans, had a more streamlined and profitable system, yielding in total 10 million gold ducats in 1527–1528 and also did not suffer from deficit.[106][107]

He often had to depend on loans from bankers. He borrowed 28 million ducats in total during his reign, of which 5.5 million ducats came from the Fuggers and 4.2 million from the Welsers of Augsburg. Other creditors were from Genoa, Antwerp and Spain.[108]

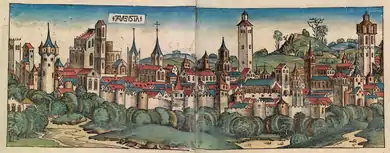

Military system

Under the organization and patronage of Maximilian I, Southern Germany had become the leading arms industry region of the sixteenth century, rivalled only by Northern Italy (with the chief centers being Nuremberg, Augsburg, Milan and Brescia).[110][111][112] Charles V continued with the development of mass production (and standardization of gun caliber), which greatly affected warfare.[113][114] The Helmschmied of Augsburg and the Negroli of Milan were among the foremost families of armourers of the time. Under Charles V, the Spanish arms industry was also significantly expanded, with significant improvements of the muskets.[115][116]

The Landsknechte, originally recruited and organized by Maximilian and Georg von Frundsberg, formed the bulk of Charles V's Imperial army. They surpassed the Swiss mercenaries in quality and quantity as the "best and most easily available mercenaries in Europe" and were considered best fighting troops in the first half of the 16th century for their brutal and ruthless efficiency, with a French saying going "a Landsknecht thrown out heaven couldn't get in hell because he would frighten the devil".[117][118][119][120] Terrence McIntosh notes that, Charles V, like his grandfather, "relied heavily on German military manpower, fearsome landsknechts, as well as redoubtable Swiss-German mercenaries. Maximilian invaded northern Italy in 1496, 1508, and repeatedly between 1509 and 1516. Soon after the imperial election in 1519, Charles V was waging war there. His overwhelmingly German troops won the battle of Pavia and captured the French king in 1525; two years later they sacked the city of Rome, murdering between six and twelve thousand residents and pillaging for eight months." His expansionist and aggressive policy, in combination with brutal behaviours of the Landsknechte, which incidentally happened right at the formation of the early modern German nation, would leave an indelible mark on the neighbours' impression of the German polity, despite the fact that in the long term, it was in general not belligerent.[121]

Charles V also favoured German heavy cavalry, although costly.[122] Many cavalrymen and noblemen fighting for Charles V were of Burgundian extraction, often part of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Italian condottieri were also recruited.

In Spain, inheriting the reform work of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, in 1536, Charles reorganized his infantry and created the first units of the tercios.[123][124][125][126][127] Later they would become, arguably, "the most formidable fighting force of the sixteenth century".[128][129] The original tercios were exclusively Spanish and this situation remained until Philip II organized the Italian tercios in 1584.[124]

Communication, diplomatic and espionage systems

The Habsburg expansion and consolidation of rule was accompanied by remarkable development of communication, diplomatic and espionage systems. In 1495, Emperor Maximilian and Franz von Taxis (from the Thurn und Taxis family) developed the Niederländische Postkurs, a postal system that connected the Low Countries with Innsbruck. The system quickly converged with the European trade system and an emerging market for news,[130] spurring a pan-Europe communication revolution[131][132] The system was developed further by Philip the Handsome, who negotiated new standards for the systems with the Taxis, and unified communication between Germany, the Netherlands, France and Spain by adding stations in Granada, Toledo, Blois, Paris and Lyon in 1505.[133]

After his father death, Charles, as Duke of Burgundy, continued to develop the system. Behringer notes that, "Whereas the status of private mail remains unclear in the treaty of 1506, it is obvious from the contract of 1516 that the Taxis company had the right to carry mail and keep the profit as long as it guaranteed the delivery of court mail at clearly defined speeds, regulated by time sheets to be filled in by the post riders on the way to their destination. In return, imperial privileges guaranteed exemption from local taxes, local jurisdiction, and military service. 21 The terminology of the early modern communications system and the legal status of its participants were invented at these negotiations."[134] He confirmed Jannetto's son Giovanni Battista as Postmaster General (chief et maistre general de noz postes par tous noz royaumes, pays, et seigneuries) in 1520. By Charles V's time, "the Holy Roman Empire had become the centre of the European communication(s) universe."[130]

Charles V also inherited efficient multinational diplomatic networks from both the Trastamara and Habsburg-Burgundian dynasties. Following the example of the papal curia, in the late fifteenth century, both dynasties also began to employ permanent envoys (earlier than other secular powers). The Habsburg network developed in parallel to their postal system.[135][136][137] Charles V combined the Spanish and the Imperial systems into one.[136] His opponents, chiefly France, found a counterweight though, by the alliance with the Ottoman Empire, which Francis I admitted to be the only force that could prevent the Habsburgs from transforming European states into a Europe-wide empire.[138] Moreover, Charles V's military might frightened other European rulers, thus while he was able to make the pope a reluctant agent like his grandfather Ferdinand had done, no lasting alliance could be achieved. After the Battle of Pavia, the European rulers united to prevent harsh terms from being placed upon France.[139]

In the 1530s, in the context of the conflict between the Habsburg empire and their greatest opponent, the Ottomans, an espionage network was built by Charles and Don Alfonso Granai Castriota, the marquis of Atripalda, who conducted its operations. Naples became the main rearguard of the system. Gennaro Varriale writes that, "on the eve of the Tunis campaign, Emperor Charles V possessed a network of spies based in the Kingdom of Naples that watched over all the corners of the Ottoman Empire."[140]

Patronage of the arts and architecture

Noted Spanish Poet Garcilaso de la Vega, was a nobleman and ambassador in the royal court of Charles. He was first appointed "contino" (imperial guard) of the King in 1520. Alfonso de Valdés, twin brother of the humanist Juan de Valdés and secretary of the emperor, was a Spanish humanist. Peter Martyr d'Anghiera was an Italian historian at the service of Spain who wrote the first accounts of explorations in Central and South America in a series of letters and reports, grouped in the original Latin publications of 1511 to 1530 into sets of ten chapters called "decades." His Decades are of great value in the history of geography and discovery. His De Orbe Novo (On the New World, 1530) describes the first contacts of Europeans and Native Americans, Native American civilizations in the Caribbean and North America, as well as Mesoamerica, and includes, for example, the first European reference to India rubber. Martyr was given the post of chronicler (cronista) in the newly formed Council of the Indies, commissioned by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor to describe what was occurring in the explorations of the New World. In 1523 Charles gave him the title of Count Palatine, and in 1524 called him once more into the Council of the Indies. Martyr was invested by Pope Clement VII, as proposed by Charles V, as Abbot of Jamaica. Juan Boscán Almogáver was a poet who participated with Garcilaso de la Vega in giving naval assistance to the Isle of Rhodes during a Turkish invasion. Boscà fought against the Turks again in 1532 with Álvarez de Toledo and Charles I in Vienna. During this period, Boscán had made serious progress in his mastery of verse in the Italian style.[141]

The Palace of Charles V was commanded by Charles, who wished to establish his residence close to the Alhambra palaces. Although the Catholic Monarchs had already altered some rooms of the Alhambra after the conquest of the city in 1492, Charles V intended to construct a permanent residence befitting an emperor. The project was given to Pedro Machuca, an architect whose life and development are poorly documented. At the time, Spanish architecture was immersed in the Plateresque style, with traces of Gothic architecture still visible. Machuca built a palace corresponding stylistically to Mannerism, a mode then in its infancy in Italy. The exterior of the building uses a typically Renaissance combination of rustication on the lower level and ashlar on the upper. The building has never been a home to a monarch and stood roofless until 1957.[142][143]

Marriage and private life

During his lifetime, Charles V had several mistresses, his step-grandmother, Germaine de Foix among them. These liaisons occurred during his bachelorhood and only once during his widowerhood; there are no records of his having any extramarital affairs during his marriage.

On 21 December 1507, Charles was betrothed to 11-year-old Mary, the daughter of King Henry VII of England and younger sister to the future King Henry VIII of England, who was to take the throne in two years. However, the engagement was called off in 1513, on the advice of Cardinal Wolsey, and Mary was instead married to King Louis XII of France in 1514.

After his ascension to the Spanish thrones, negotiations for Charles's marriage began shortly after his arrival in Castile, with the Castilian nobles expressing their wishes for him to marry his first cousin Isabella of Portugal, the daughter of King Manuel I of Portugal and Charles's aunt Maria of Aragon. The nobles desired Charles's marriage to a princess of Castilian blood, and a marriage to Isabella would have secured an alliance between Castile and Portugal. However, the 18-year-old King was in no hurry to marry and ignored the nobles' advice, exploring other marriage options.[144] Instead of marrying Isabella, he sent his sister Eleanor to marry Isabella's widowed father, King Manuel, in 1518.

In 1521, on the advice of his Flemish counsellors, especially William de Croÿ, Charles became engaged to his other first cousin, Mary, daughter of his aunt, Catherine of Aragon, and King Henry VIII, in order to secure an alliance with England. However, this engagement was very problematic because Mary was only 6 years old at the time, sixteen years Charles's junior, which meant that he would have to wait for her to be old enough to marry.

By 1525, Charles was no longer interested in an alliance with England and could not wait any longer to have legitimate children and heirs. Following his victory in the Battle of Pavia, Charles abandoned the idea of an English alliance, cancelled his engagement to Mary and decided to marry Isabella and form an alliance with Portugal. He wrote to Isabella's brother, King John III of Portugal, making a double marriage contract – Charles would marry Isabella and John would marry Charles's youngest sister, Catherine. A marriage to Isabella was more beneficial for Charles, as she was closer to him in age, was fluent in Spanish and provided him with a very handsome dowry of 900,000 Portuguese cruzados or Castilian folds that would help to solve the financial problems brought on by the Italian Wars.

On 10 March 1526, Charles and Isabella met at the Alcázar Palace in Seville. The marriage was originally a political arrangement, but on their first meeting, the couple fell deeply in love: Isabella captivated the Emperor with her beauty and charm. They were married that very same night in a quiet ceremony in the Hall of Ambassadors, just after midnight. Following their wedding, Charles and Isabella spent a long and happy honeymoon at the Alhambra in Granada. Charles began the construction of the Palace of Charles V in 1527, wishing to establish a permanent residence befitting an emperor and empress in the Alhambra palaces. However, the palace was not completed during their lifetimes and remained roofless until the late 20th century.[145]

Despite the Emperor's long absences due to political affairs abroad, the marriage was a happy one, as both partners were always devoted and faithful to each other.[146] The Empress acted as regent of Spain during her husband's absences, and she proved herself to be a good politician and ruler, thoroughly impressing the Emperor with many of her political accomplishments and decisions.

.jpg.webp)

The marriage lasted for thirteen years, until Isabella's death in 1539. The Empress contracted a fever during the third month of her seventh pregnancy, which resulted in antenatal complications that caused her to miscarry a stillborn son. Her health further deteriorated due to an infection, and she died two weeks later on 1 May 1539, aged 35. Charles was left so grief-stricken by his wife's death that for two months he shut himself up in a monastery, where he prayed and mourned for her in solitude.[147] Charles never recovered from Isabella's death, dressing in black for the rest of his life to show his eternal mourning, and, unlike most kings of the time, he never remarried. In memory of his wife, the Emperor commissioned the painter Titian to paint several posthumous portraits of Isabella; the finished portraits included Titian's Portrait of Empress Isabel of Portugal and La Gloria.[148] Charles kept these paintings with him whenever he travelled, and they were among those that he brought with him after his retirement to the Monastery of Yuste in 1557.[149]

In 1540, Charles paid tribute to Isabella's memory when he commissioned the Flemish composer Thomas Crecquillon to compose new music as a memorial to her. Crecquillon composed his Missa 'Mort m'a privé in memory of the Empress. It expresses the Emperor's grief and great wish for a heavenly reunion with his beloved wife.[150]

Siblings

| Name | Birth | Death | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eleanor | 15 November 1498 | 25 February 1558 (aged 59) | first marriage in 1518, Manuel I of Portugal and had children; second marriage in 1530, Francis I of France and had no children. |

| Isabella | 18 July 1501 | 19 January 1526 (aged 24) | married in 1515, Christian II of Denmark and had children. |

| Ferdinand | 10 March 1503 | 25 July 1564 (aged 61) | married in 1521, Anna of Bohemia and Hungary and had children. |

| Mary | 15 September 1505 | 18 October 1558 (aged 53) | married in 1522, Louis II of Hungary and Bohemia and had no children. |

| Catherine | 14 January 1507 | 12 February 1578 (aged 71) | married in 1525, John III of Portugal and had children. |

Issue

Charles and Isabella had seven legitimate children, but only three of them survived to adulthood:

| Name | Portrait | Lifespan | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Philip II of Spain |

|

21 May 1527 – 13 September 1598 |

Only surviving son, successor of his father in the Spanish crowns. |

| Maria |

|

21 June 1528 – 26 February 1603 |

Married her first cousin Maximilian II, Holy Roman Emperor. |

| Ferdinand |

.svg.png.webp) |

22 November 1529 – 13 July 1530 |

Died in infancy. |

| Son |

.svg.png.webp) |

29 June 1534 | Stillborn |

| Joanna |

|

26 June 1535 – 7 September 1573 |

Married her first cousin João Manuel, Prince of Portugal. |

| John |

.svg.png.webp) |

19 October 1537 – 20 March 1538 |

Died in infancy. |

| Son |

.svg.png.webp) |

21 April 1539 | Stillborn. |

Due to Philip II being a grandson of Manuel I of Portugal through his mother he was in the line of succession to the throne of Portugal, and claimed it after his uncle's death (Henry, the Cardinal-King, in 1580), thus establishing the personal union between Spain and Portugal.

Charles also had four illegitimate children:

- Margaret of Austria (1522–1586), daughter of Johanna Maria van der Gheynst,[151] a servant of Charles I de Lalaing, Seigneur de Montigny, daughter of Gilles Johann van der Gheynst and wife Johanna van der Caye van Cocamby. Married firstly with Alessandro de' Medici, Duke of Florence, and secondly with Ottavio Farnese, Duke of Parma.

- Joanna of Austria (1522–1530), daughter of Catalina de Rebolledo (or de Xériga), lady-in-waiting of Queen Joanna I of Castile and Aragon.[152]

- Tadea of Austria (1523? – ca. 1562), daughter of Orsolina della Penna. Married with Sinibaldo di Copeschi.

- John of Austria (1547–1578), son of Barbara Blomberg, victor of the Battle of Lepanto

Margaret of Parma

Margaret of Parma John of Austria

John of Austria

Health

Charles suffered from an enlarged lower jaw (mandibular prognathism), a congenital deformity that became considerably worse in later Habsburg generations, giving rise to the term Habsburg jaw. This deformity may have been caused by the family's long history of inbreeding, the consequence of repeated marriages between close family members, as commonly practiced in royal families of that era to maintain dynastic control of territory.[153] He suffered from epilepsy[154] and was seriously afflicted with gout, presumably caused by a diet consisting mainly of red meat.[155] As he aged, his gout progressed from painful to crippling. In his retirement, he was carried around the monastery of St. Yuste in a sedan chair. A ramp was specially constructed to allow him easy access to his rooms.[156]

Abdications and death

Between 1554 and 1556, Charles V gradually divided the Habsburg empire and the House of Habsburg between a Spanish line and a German-Austrian branch. His abdications all occurred at the Palace of Coudenberg in the city of Brussels. First he abdicated the thrones of Sicily and Naples, both fiefs of the Papacy, and the Imperial Duchy of Milan, in favour of his son Philip on 25 July 1554. Philip was secretly invested with Milan already in 1540 and again in 1546, but only in 1554 did the emperor make it public. Upon the abdications of Naples and Sicily, Philip was invested by Pope Julius III with the Kingdom of Naples on 2 October and with the Kingdom of Sicily on 18 November.[157]

The most famous—and only public—abdication took place a year later, on 25 October 1555, when Charles announced to the States General of the Netherlands (reunited in the great hall where he was emancipated exactly forty years before by Emperor Maximilian) his abdication in favour of his son of those territories as well as his intention to step down from all of his positions and retire to a monastery.[157] During the ceremony, the gout-afflicted Emperor Charles V leaned on the shoulder of his advisor William the Silent and, crying, pronounced his resignation speech:

When I was nineteen ... I undertook to be a candidate for the Imperial crown, not to increase my possessions but rather to engage myself more vigorously in working for the welfare of Germany and my other realms ... and in the hopes of thereby bringing peace among the Christian peoples and uniting their fighting forces for the defense of the Catholic faith against the Ottomans...I had almost reached my goal, when the attack by the French king and some German princes called me once more to arms. Against my enemies I accomplished what I could, but success in war lies in the hands of God, Who gives victory or takes it away, as He pleases ... I must for my part confess that I have often misled myself, either from youthful inexperience, from the pride of mature years, or from some other weakness of human nature. I nonetheless declare to you that I never knowingly or willingly acted unjustly ... If actions of this kind are nevertheless justly laid to my account, I formally assure you now that I did them unknowingly and against my own intention. I therefore beg those present today, whom I have offended in this respect, together with those who are absent, to forgive me.[158]

He concluded the speech by mentioning his voyages: ten to the Low Countries, nine to Germany, seven to Spain, seven to Italy, four to France, two to England, and two to North Africa. His last public words were, "My life has been one long journey."

With no fanfare, in 1556 he finalised his abdications. On 16 January 1556, he gave Spain and the Spanish Empire in the Americas to Philip. On 27 August 1556, he abdicated as Holy Roman Emperor in favour of his brother Ferdinand, elected King of the Romans in 1531. The succession was recognized by the prince-electors assembled at Frankfurt only in 1558, and by the Pope only in 1559.[1][159][160] The Imperial abdication also marked the beginning of Ferdinand's legal and suo jure rule in the Austrian possessions, that he governed in Charles's name since 1521–1522 and were attached to Hungary and Bohemia since 1526.[16]

According to scholars, Charles decided to abdicate for a variety of reasons: the religious division of Germany sanctioned in 1555; the state of Spanish finances, bankrupted with inflation by the time his reign ended; the revival of Italian Wars with attacks from Henri II of France; the never-ending advance of the Ottomans in the Mediterranean and central Europe; and his declining health, in particular attacks of gout such as the one that forced him to postpone an attempt to recapture the city of Metz where he was later defeated.

In September 1556, Charles left the Low Countries and sailed to Spain accompanied by Mary of Hungary and Eleanor of Austria. He arrived at the Monastery of Yuste of Extremadura in 1557. He continued to correspond widely and kept an interest in the situation of the empire, while suffering from severe gout. He lived alone in a secluded monastery, surrounded by paintings by Titian and with clocks lining every wall, which some historians believe were symbols of his reign and his lack of time.[161] In August 1558, Charles was taken seriously ill with what was later revealed to be malaria.[162] He died in the early hours of the morning on 21 September 1558, at the age of 58, holding in his hand the cross that his wife Isabella had been holding when she died.[163] Later historians claimed that, shortly prior to his death, the Emperor had ordered a mock funeral to be held for himself, during which he lay in a coffin as the monks chanted Mass. The evidence for this is dubious. Neither his physician nor his secretary mention such a thing in their letters, and it would have been against the canon law of the Catholic Church.[164]

Charles was originally buried in the chapel of the Monastery of Yuste, but he left a codicil in his last will and testament asking for the establishment of a new religious foundation in which he would be reburied with Isabella.[165] Following his return to Spain in 1559, their son Philip undertook the task of fulfilling his father's wish when he founded the Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial. After the Monastery's Royal Crypt was completed in 1574, the bodies of Charles and Isabella were relocated and re-interred into a small vault in directly underneath the altar of the Royal Chapel, in accordance with Charles's wishes to be buried "half-body under the altar and half-body under the priest's feet" side by side with Isabella. They remained in the Royal Chapel while the famous Basilica of the Monastery and the Royal tombs were still under construction. In 1654, after the Basilica and Royal tombs were finally completed during the reign of their great-grandson Philip IV, the remains of Charles and Isabella were moved into the Royal Pantheon of Kings, which lies directly under the Basilica.[166] On one side of the Basilica are bronze effigies of Charles and Isabella, with effigies of their daughter Maria of Austria and Charles's sisters Eleanor of Austria and Maria of Hungary behind them. Exactly adjacent to them on the opposite side of the Basilica are effigies of their son Philip with three of his wives and their ill-fated grandson Carlos, Prince of Asturias.

Titles

Charles V styled himself as Holy Roman Emperor after his election, according to a Papal dispensation conferred to the Habsburg family by Pope Julius II in 1508 and confirmed in 1519 to the prince-electors by the legates of Pope Leo X. Although Papal coronation was not necessary to confirm the Imperial title, Charles V was crowned in the city of Bologna by Pope Clement VII in the medieval fashion.

Charles V accumulated a large number of titles due to his vast inheritance of Burgundian, Spanish, and Austrian realms. Following the Pacts of Worms (21 April 1521) and Brussels (7 February 1522), he secretly gave the Austrian lands to his younger brother Ferdinand and elevated him to the status of Archduke. Nevertheless, according to the agreements, Charles continued to style himself as Archduke of Austria and maintained that Ferdinand acted as his vassal and vicar.[167][168] Furthermore, the pacts of 1521–1522 imposed restrictions on the governorship and regency of Ferdinand. For example, all of Ferdinand's letters to Charles V were signed "your obedient brother and servant".[169] Nonetheless, the same agreements promised Ferdinand the designation as future emperor and the transfer of hereditary rights over Austria at the imperial succession.

Following the death of Louis II, King of Hungary and Bohemia, at the Battle of Mohacs in 1526, Charles V favoured the election of Ferdinand as King of Hungary (and Croatia and Dalmatia) and Bohemia. Despite this, Charles also styled himself as King of Hungary and Bohemia and retained this titular use in official acts (such as his testament) as in the case of the Austrian lands. As a consequence, cartographers and historians have described those kingdoms both as realms of Charles V and as possessions of Ferdinand, not without confusion. Others, such as the Venetian envoys, reported that the states of Ferdinand were "all held in common with the Emperor".[170]

Therefore, although he had agreed on the future division of the dynasty between Ferdinand and Philip II of Spain, during his own reign Charles V conceived the existence of a single "House of Austria" of which he was the sole head.[171] In the abdications of 1554–1556, Charles left his personal possessions to Philip II and the Imperial title to Ferdinand. The titles of King of Hungary, of Dalmatia, Croatia, etc., were also nominally left to the Spanish line (in particular to Don Carlos, Prince of Asturias and son of Philip II). However, Charles's Imperial abdication marked the beginning of Ferdinand's suo jure rule in Austria and his other lands: despite the claims of Philip and his descendants, Hungary and Bohemia were left under the nominal and substantial rule of Ferdinand and his successors. Formal disputes between the two lines over Hungary and Bohemia were to be solved with the Onate treaty of 1617.

Charles's full titulature went as follows:

Charles, by the grace of God, Emperor of the Romans, forever August, King of Germany, King of Italy, King of all Spains, of Castile, Aragon, León, of Hungary, of Dalmatia, of Croatia, Navarra, Grenada, Toledo, Valencia, Galicia, Majorca, Sevilla, Cordova, Murcia, Jaén, Algarves, Algeciras, Gibraltar, the Canary Islands, King of both Hither and Ultra Sicily, of Sardinia, Corsica, King of Jerusalem, King of the Indies, of the Islands and Mainland of the Ocean Sea, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, Brabant, Lorraine, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Limburg, Luxembourg, Gelderland, Neopatria, Württemberg, Landgrave of Alsace, Prince of Swabia, Asturia and Catalonia, Count of Flanders, Habsburg, Tyrol, Gorizia, Barcelona, Artois, Burgundy Palatine, Hainaut, Holland, Seeland, Ferrette, Kyburg, Namur, Roussillon, Cerdagne, Drenthe, Zutphen, Margrave of the Holy Roman Empire, Burgau, Oristano and Gociano, Lord of Frisia, the Wendish March, Pordenone, Biscay, Molin, Salins, Tripoli and Mechelen.

| Title | From | To | Regnal name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Titular Duke of Burgundy | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Brabant | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Limburg | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Lothier | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Luxemburg | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles III | |

| Margrave of Namur | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Count Palatine of Burgundy | 25 September 1506 | 5 February 1556 | Charles II | |

| Count of Artois | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Count of Charolais | 25 September 1506 | 21 September 1558 | Charles II | |

| Count of Flanders | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles III | |

| Count of Hainault | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Count of Holland | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Count of Zeeland | 25 September 1506 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| King of Castile and León | 14 March 1516 | 16 January 1556 | Charles I | |

| King of Aragon and Sicily | 14 March 1516 | 16 January 1556 | Charles I | |

| Count of Barcelona | 14 March 1516 | 16 January 1556 | Charles I | |

| King of Naples | 14 March 1516 | 25 July 1554 | Charles IV | |

| Archduke of Austria | 12 January 1519 | 12 January 1521 | Charles I | |

| Holy Roman Emperor | 28 June 1519 | 27 August 1556 | Charles V | |

| King of the Romans | 23 October 1520 | 24 February 1530 | Charles V | |

| Count of Zutphen | 12 September 1543 | 25 October 1555 | Charles II | |

| Duke of Guelders | 12 September 1543 | 25 October 1555 | Charles III | |

Coat of arms of Charles V

Coat of arms of Charles I of Spain and V of the Holy Roman Empire according to the description: Arms of Charles I added to those of Castile, Leon, Aragon, Two Sicilies and Granada present in the previous coat, those of Austria, ancient Burgundy, modern Burgundy, Brabant, Flanders and Tyrol. Charles I also incorporates the pillars of Hercules with the inscription "Plus Ultra", representing the overseas Spanish empire and surrounding coat with the collar of the Golden Fleece, as sovereign of the Order ringing the shield with the imperial crown and Acola double-headed eagle of the Holy Roman Empire and behind it the Cross of Burgundy. From 1520 added to the corresponding quarter to Aragon and Sicily, one in which the arms of Jerusalem, Naples and Navarre are incorporated.

Coat of arms of King Charles I of Spain before becoming emperor of the Holy Roman Empire.

Coat of arms of King Charles I of Spain before becoming emperor of the Holy Roman Empire..svg.png.webp) Coat of Arms of Charles I of Spain, Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor.

Coat of Arms of Charles I of Spain, Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor. Arms of Charles, Infante of Spain, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, KG at the time of his installation as a knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter.

Arms of Charles, Infante of Spain, Archduke of Austria, Duke of Burgundy, KG at the time of his installation as a knight of the Most Noble Order of the Garter. Variant of the Royal Bend of Castile used by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Variant of the Royal Bend of Castile used by Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||