Coenwulf of Mercia

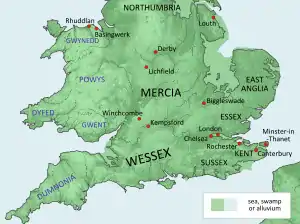

Coenwulf (Old English: [ˈkøːnwuɫf]; also spelled Cenwulf, Kenulf, or Kenwulph; Latin: Coenulfus) was the King of Mercia from December 796 until his death in 821. He was a descendant of King Pybba, who ruled Mercia in the early 7th century. He succeeded Ecgfrith, the son of Offa; Ecgfrith only reigned for five months, and Coenwulf ascended the throne in the same year that Offa died. In the early years of Coenwulf's reign he had to deal with a revolt in Kent, which had been under Offa's control. Eadberht Præn returned from exile in Francia to claim the Kentish throne, and Coenwulf was forced to wait for papal support before he could intervene. When Pope Leo III agreed to anathematise Eadberht, Coenwulf invaded and retook the kingdom; Eadberht was taken prisoner, was blinded, and had his hands cut off. Coenwulf also appears to have lost control of the kingdom of East Anglia during the early part of his reign, as an independent coinage appears under King Eadwald. Coenwulf's coinage reappears in 805, indicating that the kingdom was again under Mercian control. Several campaigns of Coenwulf's against the Welsh are recorded, but only one conflict with Northumbria, in 801, though it is likely that Coenwulf continued to support the opponents of the Northumbrian king Eardwulf.

| Coenwulf | |

|---|---|

Coenwulf's portrait from the "Coenwulf mancus", a gold coin discovered in Bedfordshire in 2001 | |

| King of Mercia | |

| Reign | 796–821 |

| Predecessor | Ecgfrith |

| Successor | Ceolwulf I |

| Died | 821 Basingwerk, Flintshire |

| Burial | Winchcombe Abbey |

| Spouse | Cynegyth (possibly) Ælfthryth |

| Issue | Cynehelm Cwoenthryth |

| House | C-dynasty |

| Father | Cuthberht |

| Religion | Christian |

Coenwulf came into conflict with Archbishop Wulfred of Canterbury over the issue of whether laypeople could control religious houses such as monasteries. The breakdown in the relationship between the two eventually reached the point where the archbishop was unable to exercise his duties for at least four years. A partial resolution was reached in 822 with Coenwulf's successor, King Ceolwulf, but it was not until about 826 that a final settlement was reached between Wulfred and Coenwulf's daughter, Cwoenthryth, who had been the main beneficiary of Coenwulf's grants of religious property.

Coenwulf was succeeded by his brother, Ceolwulf; a post-Conquest legend claims that his son Cynehelm was murdered to gain the succession. Within two years Ceolwulf had been deposed, and the kingship passed permanently out of Coenwulf's family. Coenwulf was the last king of Mercia to exercise substantial dominance over other Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. Within a decade of his death, the rise of Wessex had begun under King Egbert, and Mercia never recovered its former position of power.

Background and sources

For most of the 8th century, Mercia was dominant among the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms south of the river Humber. Æthelbald, who came to the throne in 716, had established himself as the overlord of the southern Anglo-Saxons by 731.[1] He was assassinated in 757, and was briefly succeeded by Beornred, but within a year Offa ousted Beornred and took the throne for himself. Offa's daughter Eadburh married Beorhtric of Wessex in 789, and Beorhtric became an ally thereafter.[2] In Kent, Offa intervened decisively in the 780s,[3] and at some point became the overlord of East Anglia, whose king, Æthelred, was beheaded on Offa's orders in 794.[4]

Offa appears to have moved to eliminate dynastic rivals to the succession of his son, Ecgfrith.[5] According to a contemporary letter from Alcuin of York, an English deacon and scholar who spent over a decade as a chief advisor at Charlemagne's court,[6] "the vengeance of the blood shed by the father has reached the son"; Alcuin added, "This was not a strengthening of the kingdom, but its ruin."[7] Offa died in July 796. Ecgfrith succeeded him but reigned for less than five months before Coenwulf came to the throne.[8]

A significant corpus of letters dates from the period, especially from Alcuin, who corresponded with kings, nobles, and ecclesiastics throughout England.[6] Letters between Coenwulf and the papacy also survive.[9] Another key source for the period is the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a collection of annals in Old English narrating the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The Chronicle was a West Saxon production, however, and is sometimes thought to be biased in favour of Wessex.[10] Charters dating from Coenwulf's reign have survived; these were documents granting land to followers or to churchmen and were witnessed by the kings who had the authority to grant the land.[11][12] A charter might record the names of both a subject king and his overlord on the witness list appended to the grant. Such a witness list can be seen on the Ismere Diploma, for example, where Æthelric, son of king Oshere of the Hwicce, is described as a "subregulus", or subking, of Æthelbald.[13]

Mercia and southern England at Ecgfrith's death

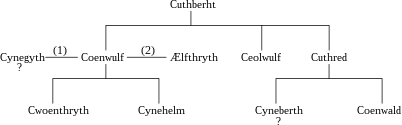

According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Ecgfrith only reigned for 141 days.[14] Offa is known to have died in 796, on either 26 July or 29 July, so Ecgfrith's date of death is either 14 December or 17 December of the same year.[15] Coenwulf succeeded Ecgfrith as king. Coenwulf's father's name was Cuthberht, who may have been the same person as an ealdorman of that name who witnessed charters during the reign of Offa.[5] Coenwulf is also recorded as witnessing charters during Offa's reign.[16] According to the genealogy of Mercian kings preserved in the Anglian collection Coenwulf was descended from a brother of Penda named Cenwealh, of whom there is no other record.[5] It is possible that this refers to Cenwealh of Wessex, who was married to (and later repudiated) a sister of Penda.[17]

Coenwulf's kin may have been connected to the royal family of the Hwicce, a subkingdom of Mercia around the lower river Severn.[18] It appears that Coenwulf's family were powerful, but they were not of recent Mercian royal lineage.[15] A letter written by Alcuin to the people of Kent in 797 laments that "scarcely anyone is found now of the old stock of kings".[19] Eardwulf of Northumbria had, like Coenwulf, gained his throne in 796, so Alcuin's meaning is not clear, but it may be that he intended it as a slur on Eardwulf or Coenwulf or on both.[20] Alcuin certainly held negative views of Coenwulf, regarding him as a tyrant and criticising him for putting aside one wife and taking another. Alcuin wrote to a Mercian nobleman to ask him to greet Coenwulf peaceably "if it is possible to do so", implying uncertainty about Coenwulf's policy towards the Carolingians.[15]

Coenwulf's early reign was marked by a breakdown in Mercian control in southern England. In East Anglia, King Eadwald minted coins at about this time, implying that he was no longer subject to Mercia.[21] A charter of 799 seems to show that Wessex and Mercia were estranged for some time before that date, though the charter is not regarded as undoubtedly genuine.[22][23] In Kent, an uprising began, probably starting after Ecgfrith's death,[21] though it has been suggested that it began much earlier in the year, before Offa's death.[24][25] The uprising was led by Eadberht Præn, who had been an exile at Charlemagne's court: Eadberht's cause almost certainly had Carolingian support.[26] Eadberht became king of Kent, and Æthelheard, the archbishop of Canterbury at that time, fled his see; it is likely that Christ Church, Canterbury was sacked.[21]

Reign

Coenwulf was unwilling to take military action in Kent without acknowledgement from Pope Leo III that Eadberht was a pretender. The basis for this assertion was that Eadberht had reportedly been a priest, and as such had given up any right to the throne.[21] Coenwulf wrote to the Pope and asked Leo to consider making London the seat of the southern archbishopric, removing the honour from Canterbury; it is likely that Coenwulf's reasons included the loss of Mercian control over Kent.[21][27] Leo refused to agree to moving the archiepiscopate to London, but in the same letter he agreed that Eadberht's previous ordination made him ineligible for the throne:[28]

And concerning that letter which the most reverend and holy Æthelheard sent to us ... as regards that apostate cleric who mounted to the throne ... we excommunicate and reject him, having regard to the safety of his soul. For if he should still persist in that wicked behaviour, be sure to inform us quickly, that we may [write to] princes and all people dwelling in the island of Britain, exhorting them to expel him from his most wicked rule and procure the safety of his soul.

This authorisation from the Pope to proceed against Eadberht was delayed until 798, but once it was received Coenwulf took action.[21] The Mercians captured Eadberht, put out his eyes and cut off his hands,[29] and led him in chains to Mercia, where according to later tradition he was imprisoned at Winchcombe, a religious house closely affiliated with Coenwulf's family.[30] By 801 at the latest Coenwulf had placed his brother, Cuthred, on the throne of Kent.[31] Cuthred ruled until the time of his death in 807, after which Coenwulf took control of Kent in name as well as fact.[32] Coenwulf styled himself "King of the Mercians and the Province of Kent" (rex Merciorum atque provincie Cancie) in a charter dated 809.[33]

Offa's domination of the kingdom of Essex was continued by Coenwulf. King Sigeric of Essex left for Rome in 798, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle,[34] presumably abdicating the throne in favour of his son, Sigered. Sigered appears on two charters of Coenwulf's in 811 as king (rex) of Essex, but his title is reduced thereafter, first to subregulus, or subking, and thereafter to dux or ealdorman.[35][36]

The course of events in East Anglia is less clear, but Eadwald's coinage ceased, and new coinage issued by Coenwulf began by about 805, so it is likely that Coenwulf forcibly re-established Mercian dominance there.[31] The resumption of friendly relations with Wessex under Beorhtric received a setback when Beorhtric died and the throne of Wessex passed to Egbert, who, like Eadberht, had been an exile at Charlemagne's court.[37] The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that on the same day that Egbert came to the throne, an ealdorman of the Hwicce named Æthelmund led a force across the Thames at Kempsford but was defeated by the men of Wiltshire under the leadership of Weohstan, also an ealdorman.[38] Egbert may also have had a claim on the Kentish throne, according to the Chronicle, but he made no move to recover it during Coenwulf's reign.[39] Egbert appears to have been independent of Mercia from the beginning of his reign, and Wessex's independence meant that Coenwulf was never able to claim the overlordship of the southern English that had belonged to Offa and Æthelbald.[24] He did, however, claim the title of "Emperor" on one charter, the only Anglo-Saxon king to do so before the 10th century.[40]

In 796 or 797 the Welsh engaged Mercian forces at Rhuddlan. By 798 Coenwulf was in a position to invade in return, killing Caradog ap Meirion, the King of Gwynedd.[41] A civil war in Gwynedd in the 810s ended with the succession of Hywel ap Caradog in 816 or 817, and Coenwulf invaded again, this time ravaging Snowdonia and taking control of Rhufuniog, a small Welsh territory near Rhos. It is not clear if the Mercians were involved in a battle recorded in Anglesey in 817 or 818, but the following year Coenwulf and his army devastated Dyfed.[42]

The Northumbrian king, Æthelred, was assassinated in April 796, and less than a month later his successor, Osbald, was deposed in favour of Eardwulf.[43] Eardwulf had Alhmund killed in 800; Alhmund was the son of King Alhred of Northumbria, who had reigned from 765 to 774. Alhmund's death was regarded as a martyrdom, and his cult subsequently developed at Derby, in Mercian territory, perhaps implying Mercian involvement in Northumbrian politics at the time. Coenwulf gave hospitality to Eardwulf's enemies, who had been exiled from Northumbria, and consequently Eardwulf invaded Mercia in 801. The invasion was inconclusive, however, and peace was arranged on equal terms. Coenwulf may also have been behind the coup in 806 that led to Eardwulf losing his throne,[44] and he likely continued to support Eardwulf's enemies after Eardwulf returned in 808.[45]

Relations with the church

In 787, Offa had persuaded the Church to create a new archbishopric at Lichfield, dividing the archdiocese of Canterbury. The new archdiocese included the sees of Worcester, Hereford, Leicester, Lindsey, Dommoc and Elmham; these were essentially the midland Anglian territories. Canterbury retained the sees in the south and southeast.[46][47] Hygeberht, already Bishop of Lichfield, was the new archdiocese's first and only archbishop.[48]

Two versions of the events that led to the creation of the new archdiocese appear in the form of an exchange of letters in 798 between Coenwulf and Pope Leo III. Coenwulf asserted in his letter that Offa wanted the new archdiocese created out of enmity for Jænberht, the Archbishop of Canterbury at the time of the division; but Leo responded that the only reason the papacy agreed to the creation was because of the size of the kingdom of Mercia.[49] The comments of both Coenwulf and Leo are partisan, as each had his own reasons for representing the situation as they did: Coenwulf was entreating Leo to make London the sole southern archdiocese, while Leo was concerned to avoid the appearance of complicity with the unworthy motives Coenwulf imputed to Offa.[50] Coenwulf's desire to move the southern archbishopric to London would have been influenced by the situation in Kent, where Archbishop Æthelheard had been forced to flee by Eadberht Præn. Coenwulf would have wished to retain control over the archiepiscopal seat, and at the time he wrote to the pope Kent was independent of Mercia.[51]

Æthelheard, who had succeeded Jaenberht in 792, had been the abbot of a monastery at Louth in Lindsey.[24] On 18 January 802 Æthelheard received a papal privilege that re-established his authority over all the churches in the archdiocese of Lichfield as well as those of Canterbury. Æthelheard held a council at Clovesho on 12 October 803 which finally stripped Lichfield of its archiepiscopal status. However, it appears that Hygeberht had already been removed from his office; a Hygeberht attended the council of Clovesho as the head of the Church in Mercia but signed as an abbot.[52]

Archbishop Æthelheard died in 805 and was succeeded by Wulfred.[53] Wulfred was given freedom to mint coins that did not name Coenwulf on the reverse, probably indicating that Wulfred was on good terms with the Mercian king. In 808 there was evidently a rift of some kind: a letter from Pope Leo to Charlemagne mentioned that Coenwulf had not yet made peace with Wulfred. After this no further discord is mentioned until 816, when Wulfred presided over a council which attacked lay control of religious houses.[54] The council, held at Chelsea, asserted that Coenwulf did not have the right to make appointments to nunneries and monasteries, although both Leo and his predecessor, Pope Hadrian I, had granted Offa and Coenwulf the right to do so. Coenwulf had recently appointed his daughter, Cwoenthryth, to the position of abbess of Minster-in-Thanet. Leo died in 816, and his successor, Stephen IV, died the following January; the new pope, Paschal I confirmed Coenwulf's privileges but this did not end the dispute.[41] In 817 Wulfred witnessed two charters in which Coenwulf granted land to Deneberht, bishop of Worcester, but there is no further record of Wulfred acting as archbishop for the rest of Coenwulf's reign.[41] One account records that the quarrel between Wulfred and Coenwulf led to Wulfred being deprived of his office for six years, with no baptisms taking place during that time, but this may have been an exaggeration, with four years being the more likely term of the suspension.[54][55]

In 821, the year of Coenwulf's death, a council was held in London at which Coenwulf threatened to exile Wulfred if the archbishop did not surrender an estate of 300 hides and make a payment of 120 pounds to the king.[41][56] Wulfred is recorded to have agreed to these terms, but the conflict continued well past Coenwulf's death, with an apparently final agreement between Wulfred and Coenwulf's daughter Cwoenthryth reached in 826 or 827. However, Wulfred officiated at the consecration of Coenwulf's brother and heir, Ceolwulf, on 17 September 822, so it is evident that some accommodation had been reached by that time. Wulfred had probably resumed his archiepiscopal duties earlier that year.[41][53]

Coinage

.jpg.webp)

The coinage of Coenwulf follows the broad silver penny format established under Offa and his contemporaries. His very first coins are very similar to the heavy coinage of Offa's last three years, and since the mints at Canterbury and in East Anglia were under the control of Eadbert Præn and Eadwald, respectively, these earliest pennies must be the product of the London mint. Before 798 the new tribrach type appeared, with a design consisting of three radial lines meeting at the centre. The tribrach design was introduced initially at London alone but soon spread to Canterbury after it was reconquered from the rebels. It was not struck in East Anglia, but there are tribrach pennies in the name of Cuthred, sub-king of Kent. Around 805 a new portrait coinage was introduced to all three of the southern mints. After around 810 a range of reverse designs was introduced, though several were common to many or all of the moneyers.[57] From this date there is also evidence of a new mint, at Rochester in Kent.[58]

A gold coin bearing the name Coenwulf was discovered in 2001 at Biggleswade in Bedfordshire, England, on a footpath beside the River Ivel. The 4.33 g (0.153 oz) mancus, worth about 30 silver pennies, is only the eighth-known Anglo-Saxon gold coin dating to the mid-to-late Anglo-Saxon period. The coin's inscription, "DE VICO LVNDONIAE", indicates that it was minted in London.[59] It has seen little or no circulation, as it was probably lost shortly after it was issued. The similarity to a coin of Charlemagne inscribed vico Duristat has been taken to suggest that the two coins reflect a rivalry between the two kings, although it is unknown which coin has priority.[60] Initially sold to American collector Allan Davisson for £230,000 at an auction held by Spink auction house in 2004, the British Government subsequently put in place an export ban in the hope of saving it for the British public.[61][62] In February 2006 the coin was bought by the British Museum for £357,832 with the help of funding from the National Heritage Memorial Fund and The British Museum Friends[63] making it the most expensive British coin purchased until then, though the price was exceeded the following July by the third-known example of a Double Leopard.[64]

Family and succession

A charter of 799 records a wife of Coenwulf named Cynegyth; the charter is forged, but this detail is possibly accurate.[65][66] Ælfthryth is more reliably established as Coenwulf's wife, again from charter evidence; she is recorded on charters dated between 804 and 817.[67] Coenwulf's daughter, Cwoenthryth, survived him and inherited the monastery at Winchcombe which Coenwulf had established as part of the patrimony of his family.[68] Cwoenthryth subsequently was engaged in a long dispute with Archbishop Wulfred over her rights to the monastery.[41] Coenwulf also had a son, Cynehelm, who later became known as a saint, with a cult dating from at least the 970s.[69] According to Alfred the Great's biographer, the Welsh monk and bishop, Asser, Alfred's wife Ealhswith was descended from Coenwulf through her mother, Eadburh, though Asser does not say which of Coenwulf's children Eadburh descends from.[70]

Coenwulf died in 821 at Basingwerk near Holywell, Flintshire, probably while making preparations for a campaign against the Welsh that took place under his brother and successor, Ceolwulf, the following year.[71] Coenwulf's body was moved to Winchcombe where it was buried in St Mary's Abbey[72] (later known as Winchcombe Abbey). A mid-11th-century source asserts that Cynehelm briefly succeeded to the throne while still a child and was then murdered by his tutor Æscberht at the behest of Cwoenthryth. This version of events "bristles with historical problems", according to one historian, and it is also possible that Cynehelm is to be identified with an ealdorman who is found witnessing charters earlier in Coenwulf's reign, and who appears to have died by about 812.[69][73] The opinion of historians is not unanimous on this point: Simon Keynes has suggested that the ealdorman is unlikely to be the same person as the prince and that Cynehelm therefore may well have survived to the end of his father's reign.[8] Regardless of interpretation of Cynehelm's legend, there does appear to have been dynastic discord early in Ceolwulf's reign: a document from 825 says that after the death of Coenwulf "much discord and innumerable disagreements arose between various kings, nobles, bishops and ministers of the Church of God on very many matters of secular business".[42]

Coenwulf was the last of a series of Mercian kings, beginning with Penda in the early 7th century, to exercise dominance over most or all of southern England. In the years after his death, Mercia's position weakened, and the battle of Ellendun in 825 firmly established Egbert of Wessex as the dominant king south of the Humber.[74]

The Anglo-Saxonist and historian John Blair has identified evidence that Coenwulf came to be venerated as a saint, at least by the 12th century, and included him in his 'Handlist of Anglo-Saxon Saints'. The evidence is that the king appears to have been honoured as a 'holy benefactor' [Blair] at Winchcombe Abbey in the 12th century, and that a relic of Sanctus Kenulfus appears in a 12th-century relic list from Peterborough Abbey.[75]

See also

- Kings of Mercia family tree

Notes

- Simon Keynes, "Mercia", in Lapidge et al., Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 306.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 210.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 167.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 64.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 118.

- Lapidge, "Alcuin of York", in Lapidge et al., "Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England", p. 24.

- Letter of Alcuin to Mercian ealdorman Osbert, tr. in Whitelock, English Historical Documents, p. 787

- Simon Keynes, "Coenwulf", in Lapidge et al., Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England, p. 111.

- See the exchange of letters between Coenwulf and Pope Leo III in Whitelock, English Historical Documents, 204 and 205, pp. 791–794.

- Campbell, Anglo-Saxon State, p. 144.

- Hunter Blair, Roman Britain, pp. 14–15.

- Campbell, The Anglo-Saxons, pp. 95–98.

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, 67, pp. 453–454.

- Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, p. 50.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 177.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 120.

- Williams, Kingship and Government, p. 29.

- Sarah and John Zaluckyj, "Decline", in Zaluckyj and Zaluckyj, Mercia, p. 228.

- Story, Carolingian Connections, p. 145.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 156.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 178.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 179 and n. 122, p. 184.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net: S 154". Sean Miller. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 225.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 183, n. 8, quoting Brooks, The Early History of the Church of Canterbury

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 185.

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, 204, p. 791.

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, 205, p. 793.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 121.

- Story, Carolingian Connections, p. 142.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 179.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 32.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net: S 164". Sean Miller. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, p. 56.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 51.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 305.

- Sarah and John Zaluckyj, "Decline", in Zaluckyj & Zaluckyj, Mercia, p. 232.

- Swanton, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, pp. 58–59.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 189.

- Patrick Wormald, "The Age of Offa and Alcuin", in Campbell et al. The Anglo-Saxons, p. 101.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 187.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 188.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 155.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 95.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 197.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 174.

- According to Brooks, the earliest source for the list of dioceses attached to Lichfield is the 12th-century William of Malmesbury; Brooks emphasizes that this is a late source, though he acknowledges the division given is plausible. Brooks, Early History, p. 119.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 217–218 & 218 notes 3 & 4.

- Whitelock, English Historical Documents, 204 & 205, pp. 791–794.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, pp. 169–170.

- Brooks, Early History of Canterbury, pp. 120–125.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 227.

- S.E. Kelly, "Wulfred", in Lapidge et al., Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon History, p. 491.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 186.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 229 n. 5.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, pp. 229–230.

- Blackburn & Grierson, Medieval European Coinage, pp. 284–288.

- Gareth Williams, "Mercian Coinage and Authority", in Brown and Farr, Mercia, p. 221.

- EMC Number 2004.167, Early Medieval Corpus, Fitzwilliam Museum. Now British Museum nr. 2006,0204.1.

-

- Gareth Williams, Early Anglo-Saxon Coins (2008), 43–45.

- John Blair, Building Anglo-Saxon England (2018), p. 230.

- "Ancient coin could fetch £150,000", BBC.

- Healey, "Museum Buying Rare Coin to Keep It in Britain".

- "Coenwulf mancus". British Museum. 2006.

- "Rare Coin Breaks Auction Record", BBC.

- "Anglo-Saxons.net: S 156". Sean Miller. Retrieved 2 February 2008.

- Pauline Stafford, "Political Womena", in Brown & Farr, Mercia, p. 42, n. 5.

- Ælfthryth 3, PASE.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 118–119.

- Thacker, "Kings, Saints and Monasteries", p. 8.

- Kirby, Earliest English Kings, p. 212.

- Stenton, Anglo-Saxon England, p. 230.

- Sims-Williams, Patrick (2005). Religion and Literature in Western England, 600–800. ISBN 978-0521673426.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, p. 119.

- Yorke, Kings and Kingdoms, pp. 104–105, 112, 122.

- John Blair, 'A Handlist of Anglo-Saxon Saints', in Thacker, Alan; Sharpe, Richard (2002). Local Saints and Local Churches in the Early Medieval West. Oxford University Press. pp. 495–565. ISBN 0198203942., at p. 521, where as indicated in Blair's introduction (at p. 495) the italicization of his name signals that his holiness is attested only in post-Conquest evidence and thus that his status as a pre-Conquest saint is hypothetical.

References

Primary sources

- Keynes, Simon; Lapidge, Michael (2004). Alfred the Great: Asser's Life of King Alfred and other contemporary sources. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0-14-044409-4.

- Bede (1991). D.H. Farmer (ed.). Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Translated by Leo Sherley-Price. Revised by R.E. Latham. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044565-7.

- Ælfthryth 3 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England. Retrieved 2008-02-09.

- Swanton, Michael (1996). The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-92129-9.

- Whitelock, Dorothy (1968). English Historical Documents Volume I c. 500–1042. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

Secondary sources

- "Ancient coin could fetch £150,000". BBC. 6 October 2004. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- "Museum's £350,000 deal for coin". BBC. 8 February 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- "Rare Coin Breaks Auction Record". BBC. 29 June 2006. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- Blackburn, Mark & Grierson, Philip, Medieval European Coinage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, reprinted with corrections 2006. ISBN 0-521-03177-X

- Blair, John, 'A Handlist of Anglo-Saxon Saints', in Thacker, Alan; Sharpe, Richard (2002). Local Saints and Local Churches in the Early Medieval West. Oxford University Press. pp. 495–565. ISBN 0198203942.

- Blair, John (2006). The Church in Anglo-Saxon Society. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-921117-3.

- Blunt, C.E.; Lyon, C.S.S. & Stewart, B.H. "The coinage of southern England, 796–840", British Numismatic Journal 32 (1963), 1–74

- Brooks, Nicholas (1984). The Early History of the Church of Canterbury: Christ Church from 597 to 1066. London: Leicester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7185-0041-2.

- Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

- Campbell, James (2000). The Anglo-Saxon State. Hambledon and London. ISBN 978-1-85285-176-7.

- Campbell, James; John, Eric; Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-014395-9.

- "Early Medieval Corpus of Coin Finds, 410–1180". Early Medieval Corpus. The Fitzwilliam Museum. Archived from the original on 18 February 2008. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- Kelly, S.E., "Wulfred", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Keynes, Simon, "Mercia", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Keynes, Simon, "Offa", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Keynes, Simon, "Mercia and Wessex in the Ninth Century", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

- Kirby, D.P. (1992). The Earliest English Kings. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-09086-5.

- Lapidge, Michael, "Alcuin of York", in Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Lapidge, Michael (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopaedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- Nelson, Janet, "Carolingian Contacts", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

- Healey, Matthew (6 February 2006). "Museum Buying Rare Coin to Keep It in Britain". New York Times. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- Stafford, Pauline, "Political Women in Mercia, Eighth to Early Tenth Centuries", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

- Stenton, Frank M. (1971). Anglo-Saxon England. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-821716-9.

- Story, Joanna (2003). Carolingian Connections: Anglo-Saxon England and Carolingian Francia, c. 750–870. Aldershot: Ashgate. ISBN 978-0-7546-0124-1.

- Thacker, Alan (1985). "Kings, Saints and Monasteries in Pre-Viking Mercia" (PDF). Midland History. 10: 1–25. doi:10.1179/mdh.1985.10.1.1. ISSN 0047-729X. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 10 January 2008.

- Williams, Ann (1999). Kingship and Government in Pre-Conquest England c. 500–1066. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-56797-5.

- Williams, Gareth, "Mercian Coinage and Authority", in Brown, Michelle P.; Farr, Carole A. (2001). Mercia: An Anglo-Saxon kingdom in Europe. Continuum. ISBN 978-0-8264-7765-1.

- Wormald, Patrick, "The Age of Offa and Alcuin", in Campbell, James; John, Eric; Wormald, Patrick (1991). The Anglo-Saxons. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-014395-9.

- Yorke, Barbara (1990). Kings and Kingdoms of Early Anglo-Saxon England. London: Seaby. ISBN 978-1-85264-027-9.

External links

- Cenwulf 3 at Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England