Chicken as food

Chicken is the most common type of poultry in the world.[1] Owing to the relative ease and low cost of raising chickens—in comparison to mammals such as cattle or hogs—chicken meat (commonly called just "chicken") and chicken eggs have become prevalent in numerous cuisines.

Whole chickens for sale in a public market, Mazatlan, Sinaloa, Mexico | |

| Course | Starter, main meal, side dish |

|---|---|

| Serving temperature | Hot and cold |

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 916 kJ (219 kcal) |

0.00 g | |

12.56 g | |

| Saturated | 3.500 g |

| Monounsaturated | 4.930 g |

| Polyunsaturated | 2.740 g |

Protein | 24.68 g |

| Tryptophan | 0.276 g |

| Threonine | 1.020 g |

| Isoleucine | 1.233 g |

| Leucine | 1.797 g |

| Lysine | 2.011 g |

| Methionine | 0.657 g |

| Cystine | 0.329 g |

| Phenylalanine | 0.959 g |

| Tyrosine | 0.796 g |

| Valine | 1.199 g |

| Arginine | 1.545 g |

| Histidine | 0.726 g |

| Alanine | 1.436 g |

| Aspartic acid | 2.200 g |

| Glutamic acid | 3.610 g |

| Glycine | 1.583 g |

| Proline | 1.190 g |

| Serine | 0.870 g |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Vitamin A equiv. | 6% 44 μg |

| Pantothenic acid (B5) | 13% 0.667 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Iron | 9% 1.16 mg |

| Sodium | 4% 67 mg |

| Other constituents | Quantity |

| Water | 63.93 g |

Not including 35% bones | |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA FoodData Central | |

Chicken can be prepared in a vast range of ways, including baking, grilling, barbecuing, frying, and boiling. Since the latter half of the 20th century, prepared chicken has become a staple of fast food. Chicken is sometimes cited as being more healthful than red meat, with lower concentrations of cholesterol and saturated fat.[2]

The poultry farming industry that accounts for chicken production takes on a range of forms across different parts of the world. In developed countries, chickens are typically subject to intensive farming methods while less-developed areas raise chickens using more traditional farming techniques. The United Nations estimates there to be 19 billion chickens on Earth today, making them outnumber humans more than two to one.[3]

History

The modern chicken is a descendant of red junglefowl hybrids along with the grey junglefowl first raised thousands of years ago in the northern parts of the Indian subcontinent.[4]

Chicken as a meat has been depicted in Babylonian carvings from around 600 BC.[5] Chicken was one of the most common meats available in the Middle Ages.[6][7] For thousands of years, a number of different kinds of chicken have been eaten across most of the Eastern hemisphere,[8] including capons, pullets, and hens. It was one of the basic ingredients in blancmange, a stew usually consisting of chicken and fried onions cooked in milk and seasoned with spices and sugar.[9]

In the United States in the 1800s, chicken was more expensive than other meats and it was "sought by the rich because [it is] so costly as to be an uncommon dish."[10] Chicken consumption in the U.S. increased during World War II due to a shortage of beef and pork.[11] In Europe, consumption of chicken overtook that of beef and veal in 1996, linked to consumer awareness of Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (mad cow disease).[12]

Chicken wings being barbecued

Chicken wings being barbecued Fried chicken

Fried chicken

Breeding

Modern varieties of chicken such as the Cornish Cross, are bred specifically for meat production, with an emphasis placed on the ratio of feed to meat produced by the animal. The most common breeds of chicken consumed in the U.S. are Cornish and White Rock.[13]

Chickens raised specifically for food are called broilers. In the U.S., broilers are typically butchered at a young age. Modern Cornish Cross hybrids, for example, are butchered as early as 8 weeks for fryers and 12 weeks for roasting birds.

Capons (castrated cocks) produce more and fattier meat. For this reason, they are considered a delicacy and were particularly popular in the Middle Ages.

Edible components

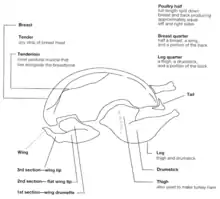

- Main

- Breast: These are white meat and are relatively dry. The breast has two segments which are sold together on bone-in breasts, but separated on boneless breasts:

- The "breast", when sold as boneless, and

- two "tenderloin", located on each side between the breast meat and the ribs. These are removed from boneless breasts and sold separately as tenderloins.[15]

- Leg: Comprises two segments:

- The "drumstick"; this is dark meat and is the lower part of the leg,

- the "thigh"; also dark meat, this is the upper part of the leg.

- Wing: Often served as a light meal or bar food. Buffalo wings are a typical example. Comprises three segments:

- the "drumette", shaped like a small drumstick, this is white meat,

- the middle "flat" segment, containing two bones, and

- the tip, often discarded.

- Breast: These are white meat and are relatively dry. The breast has two segments which are sold together on bone-in breasts, but separated on boneless breasts:

- Other

- Chicken feet: These contain relatively little meat, and are eaten mainly for the skin and cartilage. Although considered exotic in Western cuisine, the feet are common fare in other cuisines, especially in the Caribbean, China and Vietnam.

- Giblets: organs such as the heart, gizzards, and liver may be included inside a butchered chicken or sold separately.

- Head: Considered a delicacy in China, the head is split down the middle, and the brains and other tissue is eaten.

- Kidneys: Normally left in when a broiler carcass is processed, they are found in deep pockets on each side of the vertebral column.

- Neck: This is served in various Asian dishes. It is stuffed to make helzel among Ashkenazi Jews.

- Oysters: Located on the back, near the thigh, these small, round pieces of dark meat are often considered to be a delicacy.[16]

- Pygostyle (chicken's buttocks) and testicles: These are commonly eaten in East Asia and some parts of South East Asia.

- By-products

- Blood: Immediately after slaughter, blood may be drained into a receptacle, which is then used in various products. In many Asian countries, the blood is poured into low, cylindrical forms, and left to congeal into disc-like cakes for sale. These are commonly cut into cubes, and used in soup dishes.

- Carcass: After the removal of the flesh, this is used for soup stock.[17]

- Chicken eggs: The most well-known and well-consumed byproduct.

- Heart and gizzard: in Brazilian churrascos, chicken hearts are an often seen as a delicacy.[18]

- Liver: This is the largest organ of the chicken, and is used in such dishes as Pâté and chopped liver.

- Schmaltz: This is produced by rendering the fat, and is used in various dishes.

Health

Chicken meat contains about two to three times as much polyunsaturated fat as most types of red meat when measured as weight percentage.[19]

Chicken generally includes low fat in the meat itself (castrated roosters excluded). The fat is highly concentrated on the skin. A 100g serving of baked chicken breast contains 4 grams of fat and 31 grams of protein, compared to 10 grams of fat and 27 grams of protein for the same portion of broiled, lean skirt steak.[20][21]

Use of Roxarsone in chicken production

In factory farming, chickens are routinely administered with the feed additive Roxarsone, an organoarsenic compound which partially decomposes into inorganic arsenic compounded in the flesh of chickens, and in their feces, which are often used as a fertilizer.[22] The compound is used to control stomach pathogens and promote growth. In a 2013 sample conducted by the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health of chicken meat from poultry producers that did not prohibit roxarsone, 70% of the samples in the US had levels which exceeded the safety limits as set by the FDA.[23] The FDA has since revised its stance on safe limits to inorganic arsenic in animal feed by stating that "any new animal drug that contributes to the overall inorganic arsenic burden is of potential concern".[24]

Antibiotic resistance

Information obtained by the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance (CIPARS) "strongly indicates that cephalosporin resistance in humans is moving in lockstep with the use of the drug in poultry production". According to the Canadian Medical Association Journal, the unapproved antibiotic ceftiofur is routinely injected into eggs in Quebec and Ontario to discourage infection of hatchlings. Although the data are contested by the industry, antibiotic resistance in humans appears to be directly related to the antibiotic's use in eggs.[25]

A recent study by the Translational Genomics Research Institute showed that nearly half (47%) of the meat and poultry in US grocery stores was contaminated with S. aureus, with more than half (52%) of those bacteria resistant to antibiotics.[26] Furthermore, as per the FDA, more than 25% of retail chicken is resistant to 5 or more different classes of antibiotic treatment drugs in the United States.[27] An estimated 90–100% of conventional chicken contains, at least, one form of antibiotic resistance microorganism, while organic chicken has been found to have a lower incidence at 84%.[28][29]

Fecal matter contamination

In random surveys of chicken products across the United States in 2012, the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine found 48% of samples to contain fecal matter. On most commercial chicken farms, the chickens spend their entire life standing in, lying on, and living in their own manure, which is somewhat mixed in with the bedding material (e.g., sawdust, wood shavings, chopped straw, etc.).

During shipping from the concentrated animal feeding operation farm to the abattoir, the chickens are usually placed inside shipping crates that usually have slatted floors. Those crates are then piled 5 to 10 rows high on the transport truck to the abattoir. During shipment, the chickens tend to defecate, and that chicken manure tends to sit inside the crowded cages, contaminating the feathers and skin of the chickens, or rains down upon the chickens and crates on the lower levels of the transport truck. By the time the truck gets to the abattoir, most chickens have had their skin and feathers contaminated with feces.

There is also fecal matter in the intestines. While the slaughter process removes the feathers and intestines, only visible fecal matter is removed.[30] The high speed automated processes at the abattoir are not designed to remove this fecal contamination on the feather and skin. The high speed processing equipment tend to spray the contamination around to the birds going down the processing line, and the equipment on the line itself. At one or more points on most abattoirs, chemical sprays and baths (e.g., bleach, acids, peroxides, etc.) are used to partially rinse off or kill this bacterial contamination. Unfortunately, the fecal contamination, once it has occurred, especially in the various membranes between the skin and muscle, is impossible to completely remove.

Marketing and sales

Chicken is sold both as whole birds and broken down into pieces.

In the United Kingdom, juvenile chickens of less than 28 days of age at slaughter are marketed as poussin. Mature chicken is sold as small, medium or large.

In the United States, whole mature chickens are marketed as fryers, broilers, and roasters. Fryers are the smallest size (2.5-4 lbs dressed for sale), and the most common, as chicken reach this size quickly (about 7 weeks). Broilers are larger than fryers. Roasters, or roasting hens, are the largest chickens commonly sold (3–5 months and 6-8 lbs) and are typically more expensive. Even larger and older chickens are called stewing chickens but these are no longer usually found commercially. The names reflect the most appropriate cooking method for the surface area to volume ratio. As the size increases, the volume (which determines how much heat must enter the bird for it to be cooked) increases faster than the surface area (which determines how fast heat can enter the bird). For a fast method of cooking, such as frying, a small bird is appropriate: frying a large piece of chicken results in the inside being undercooked when the outside is ready.

Chicken is also sold broken down into pieces. Such pieces usually come from smaller birds that would qualify as fryers if sold whole. Pieces may include quarters, or fourths of the chicken. A chicken is typically cut into two leg quarters and two breast quarters. Each quarter contains two of the commonly available pieces of chicken. A leg quarter contains the thigh, drumstick and a portion of the back; a leg has the back portion removed. A breast quarter contains the breast, wing and portion of the back; a breast has the back portion and wing removed. Pieces may be sold in packages of all of the same pieces, or in combination packages. Whole chicken cut up refers to either the entire bird cut into 8 individual pieces. (8-piece cut); or sometimes without the back. A 9-piece cut (usually for fast food restaurants) has the tip of the breast cut off before splitting. Pick of the chicken, or similar titles, refers to a package with only some of the chicken pieces, typically the breasts, thighs, and legs without wings or back. Thighs and breasts are sold boneless or skinless. Chicken livers and gizzards are commonly available packaged separately. Other parts of the chicken, such as the neck, feet, combs, etc. are not widely available except in countries where they are in demand, or in cities that cater to ethnic groups who favor these parts.

Worldwide, there are many fast food restaurant chains that sell exclusively or primarily poultry products including KFC (global), Red Rooster (Australia), Hector Chicken (Belgium) and CFC (Indonesia). Most of the products on the menus in such eateries are fried or breaded and are served with french fries.

Cooking

Raw chicken may contain Salmonella. The safe minimum cooking temperature recommended by the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services is 165 °F (74 °C) to prevent foodborne illness because of bacteria and parasites.[31] However, in Japan raw chicken is sometimes consumed in a dish called torisashi, which is sliced raw chicken served in sashimi style. Another preparation is toriwasa which is lightly seared on the outsides while the inside remains raw.[32]

Chicken can be cooked in many ways. It can be made into sausages, skewered, put in salads, traditionally grilled or by using electric grill, breaded and deep-fried, or used in various curries. There is significant variation in cooking methods amongst cultures. Historically common methods include roasting, baking, broasting, and frying. Western cuisine frequently has chicken prepared by deep frying for fast foods such as fried chicken, chicken nuggets, chicken lollipops or Buffalo wings. They are also often grilled for salads or tacos.

Chickens often come with labels such as "roaster", which suggest a method of cooking based on the type of chicken. While these labels are only suggestions, ones labeled for stew often do not do well when cooked with other methods.[33]

Some chicken breast cuts and processed chicken breast products include the moniker "with rib meat". This is a misnomer, as it refers to the small piece of white meat that overlays the scapula, removed along with the breast meat. The breast is cut from the chicken and sold as a solid cut, while the leftover breast and true rib meat is stripped from the bone through mechanical separation for use in chicken franks, for example. Breast meat is often sliced thinly and marketed as chicken slices, an easy filling for sandwiches. Often, the tenderloin (pectoralis minor) is marketed separately from the breast (pectoralis major). In the US, "tenders" can be either tenderloins or strips cut from the breast. In the UK the strips of pectoralis minor are called "chicken mini-fillets".

Chicken bones are hazardous to health as they tend to break into sharp splinters when eaten, but they can be simmered with vegetables and herbs for hours or even days to make chicken stock.

In Asian countries it is possible to buy bones alone as they are very popular for making chicken soups, which are said to be healthy. In Australia the rib cages and backs of chickens after the other cuts have been removed are frequently sold cheaply in supermarket delicatessen sections as either "chicken frames" or "chicken carcasses" and are purchased for soup or stock purposes.

Marination of chicken

Marination of chicken.jpg.webp) Roasted chicken with vegetable chowder sauce

Roasted chicken with vegetable chowder sauce Chicken with mushrooms, tomatoes and spices

Chicken with mushrooms, tomatoes and spices Oven roasted chicken with potatoes

Oven roasted chicken with potatoes Chicken tikka masala, adapted from Indian chicken tikka and called "a true British national dish." The dish is now popular staple in Indian restaurants worldwide.[34]

Chicken tikka masala, adapted from Indian chicken tikka and called "a true British national dish." The dish is now popular staple in Indian restaurants worldwide.[34] A chicken curry from Maharashtra, India with rice flour chapatis. The dish is popular worldwide.[35]

A chicken curry from Maharashtra, India with rice flour chapatis. The dish is popular worldwide.[35] Peking chicken from the Philippines

Peking chicken from the Philippines Butter chicken from India

Butter chicken from India A meal consisting of chicken served with carrots and rice.

A meal consisting of chicken served with carrots and rice. Chicken sizzler is served on high temperature in heavy wood utensils.

Chicken sizzler is served on high temperature in heavy wood utensils.

Freezing

Raw chicken maintains its quality longer than fresh in the freezer, as moisture is lost during cooking.[36] There is little change in nutrient value of chicken during freezer storage.[36] For optimal quality, however, a maximum storage time in the freezer of 12 months is recommended for uncooked whole chicken, 9 months for uncooked chicken parts, 3 to 4 months for uncooked chicken giblets, and 4 months for cooked chicken.[36] Freezing does not usually cause color changes in poultry, but the bones and the meat near them can become dark. This bone darkening results when pigment seeps through the porous bones of young poultry into the surrounding tissues when the poultry meat is frozen and thawed.[36]

It is safe to freeze chicken directly in its original packaging, but this type of wrap is permeable to air and quality may diminish over time. Therefore, for prolonged storage, it is recommended to overwrap these packages.[36] It is recommended to freeze unopened vacuum packages as is.[36] If a package has accidentally been torn or has opened while food is in the freezer, the food is still safe to use, but it is still recommended to overwrap or rewrap it.[36] Chicken should be away from other foods, so if they begin to thaw, their juices will not drip onto other foods.[36] If previously frozen chicken is purchased at a retail store, it can be refrozen if it has been handled properly.[36]

Bacteria survives but does not grow in freezing temperatures. However, if frozen cooked foods are not defrosted properly and are not reheated to temperatures that kill bacteria, chances of getting a foodborne illness greatly increase.[37]

See also

- Barbecue chicken

- Battery cage

- Bush legs

- Chickens as pets

- Chicken soup

- Chicken tabaka

- Chicken patty

- Cornish game hen

- List of chicken dishes

- Poultry farming

- Woody breast

References

- "FAOSTAT: Production_LivestockPrimary_E_All_Data". Food and Agriculture Organization. 2014. Retrieved 14 March 2017.

- "Eat More Chicken, Fish and Beans". www.heart.org.

- "How many chickens on Earth?". cnn.com.

- Eriksson J, Larson G, Gunnarsson U, Bed'hom B, Tixier-Boichard M, et al. (2008) Identification of the Yellow Skin Gene Reveals a Hybrid Origin of the Domestic Chicken. PLoS Genet 23 January 2008.

- Chicken facts and origins at Poultrymad

- Slavin, Philip (2009). "Chicken Husbandry in Late-Medieval Eastern England: c. 1250-1400". Anthropozoologica. 44 (2): 36. doi:10.5252/az2009n2a2. S2CID 54596878 – via Academia.edu.

Chicken meat constituted an important part of everyday diet, and it was afforded by virtually every social stratum both in England and the Continent.

- Scully, Terence (1995). The Art of Cookery in the Middle Ages. Woodbridge, UK: The Boydell Press. p. 29.

Chicken and chicken eggs were, then as now, vital staples. In part this was due to a perception that both of these foodstuffs were endowed with qualities that made them both nutritious and readily digestible. In part, too, their popularity derived from their ubiquitous availability, and hence their relative affordability.

- Twitty, Michael W. (2011). "Chickens". In Katz-Hyman, Martha B.; Rice, Kym S. (eds.). World of a Slave: Encyclopedia of the Material Life of Slaves in the United States. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. p. 108. ISBN 978-0313349423.

In ancient times, the chicken spread widely across the Eastern Hemisphere, arriving in Africa from various points east and north.

- Adler, Tamar (26 May 2016). "Trembling Before Blancmange". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

I like the economy of its ingredient list, even in medieval versions: almond milk, chicken, sugar, rosewater. In the mid-17th century, the chicken — exhausted by the centuries of labor — dropped out, replaced by the thickener isinglass, then sea moss or cornstarch or gelatin. But it stayed simple.

- Rude, Emelyn. "How Chicken Conquered the American Dinner Plate". First We Feast. Retrieved 25 August 2016.

- Poultry Farming Archived 18 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The History Channel. 2 March 2007.

- "BBC survey another blow against UK chicken". FoodProductionDaily.com. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 11 July 2007.

- Focus On: Chicken Archived 19 May 2004 at the Wayback Machine, USDA. 2 March 2007.

- Peggy Trowbridge Filippone. "Buffalo Wings History - The origins of Buffalo Chicken Wings". About.com. Retrieved 20 January 2008.

- "What is a Chicken Tenderloin?". 4thegrill.com. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- "How to Carve Chicken and Turkey". Cooks.com. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- Brown, Alton. "Chicken Stock". Food Network. Retrieved 16 August 2016.

- "Brazilian barbecued chicken hearts". Bite.co.nz. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- "Feinberg School > Nutrition > Nutrition Fact Sheet: Lipids, Northwestern University". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 9 April 2011.

- "Nutrition Facts - 100g Chicken Breast". self.com.

- "Nutrition Facts - 100g Lean Skirt Steak". self.com.

- ""Arsenic In Chicken Production", Chemical & Engineering News, April 9, 2007, Volume 85, Number 15, pages 34-35". acs.org.

- Nachman, Keeve E.; Baron, Patrick A.; Raber, Georg; Francesconi, Kevin A.; Navas-Acien, Ana; Love, David C. (1 July 2013). "Roxarsone, inorganic arsenic, and other arsenic species in chicken: a U.S.-based market basket sample". Environmental Health Perspectives. 121 (7): 818–824. doi:10.1289/ehp.1206245. ISSN 1552-9924. PMC 3701911. PMID 23694900.

- Kawalek, JC (10 February 2011). "Provide data on various arsenic species present in broilers treated with roxarsone: Comparison with untreated birds" (PDF). The Food and Drug Administration. The Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- Gulli, Cathy (17 June 2009). "Playing chicken with antibiotics Antibiotics injected into chicken eggs is making Canadians resistant to meds". Maclean's Magazine. Retrieved 24 June 2009.

- "US Meat and Poultry Is Widely Contaminated With Drug-Resistant Staph Bacteria". sciencedaily.com.

- "Retail Meat Report" (PDF). National Antimicrobial Resistance Monitoring System. Food and Drug Safety Administration. 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- Cohen Stuart, James; van den Munckhof, Thijs; Voets, Guido; Scharringa, Jelle; Fluit, Ad; Hall, Maurine Leverstein-Van (15 March 2012). "Comparison of ESBL contamination in organic and conventional retail chicken meat". International Journal of Food Microbiology. 154 (3): 212–214. doi:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.12.034. ISSN 1879-3460. PMID 22260927.

- Folster, J. P.; Pecic, G.; Singh, A.; Duval, B.; Rickert, R.; Ayers, S.; Abbott, J.; McGlinchey, B.; Bauer-Turpin, J. (1 July 2012). "Characterization of extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg isolated from food animals, retail meat, and humans in the United States 2009". Foodborne Pathogens and Disease. 9 (7): 638–645. doi:10.1089/fpd.2012.1130. ISSN 1556-7125. PMC 4620655. PMID 22755514.

- The Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (April 2012). "Fecal Contamination in Retail Chicken Products". Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- "Safe Minimum Cooking Temperatures". U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- "Torisashi and Toriwasa". Seafco. Inc. Archived from the original on 28 February 2014. Retrieved 28 February 2014.

- How to Buy: 5 Things to Keep in Mind Archived 2 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Food Network. 2 March 2007.

- "Robin Cook's chicken tikka masala speech". The Guardian. London. 25 February 2002. Retrieved 19 April 2001.

- Colleen Taylor Sen (15 November 2009). Curry: A Global History. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-704-6.

- Home / Fact Sheets / Safe Food Handling / Freezing and Food Safety from USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service. Last Modified: 3 June 2010.

- Julie, Garden-Robinson (January 2012). "Food Safety Basics" (PDF). NDSU Extension Service. Retrieved 1 April 2016.

External links

Media related to Chicken as food at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chicken as food at Wikimedia Commons- Foodnetwork.com page on use of chicken in cooking

- US government fact sheet on chicken as food