Islam in China

Islam has been practiced in China since the 7th century CE.[1] Muslims are a minority group in China, representing 0.45 to 2.85 percent of the total population, according to various estimates.[2][3][4] Though Hui Muslims are the most numerous group,[5][6] the greatest concentration of Muslims are in Xinjiang, which contains a significant Uyghur population. Lesser yet significant populations reside in the regions of Ningxia, Gansu and Qinghai.[7] Of China's 55 officially recognized minority peoples, ten of these groups are predominantly Sunni Muslim.[7]

| Part of a series on Islam in China |

|---|

.jpg.webp) |

|

|

History

The Silk Road, which was a series of extensive inland trade routes that spread all over the Mediterranean to East Asia, was used since 1000 BCE and continued to be used for millennia. For more than half of this long period of time, most of the traders were Muslim and moved towards the East. Not only did these traders bring their goods, they also carried with them their culture and beliefs to East Asia.[8] Islam was one of the many religions that gradually began to spread across the Silk Road during the "7th to the 10th centuries through war, trade and diplomatic exchanges".[9]

Tang dynasty

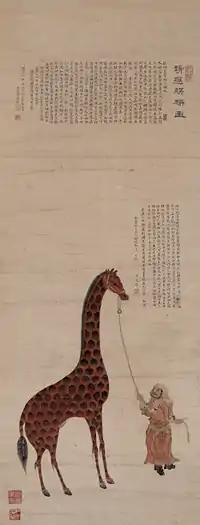

According to Chinese Muslims' traditional accounts, Islam was first introduced to China in 616–18 CE by the Sahaba (companions) of the Islamic prophet Muhammad: Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas, Sayid, Wahab ibn Abu Kabcha and another Sahaba.[10][11] It is noted in other accounts that Wahab Abu Kabcha reached Canton by sea in 629 CE.[12] The introduction of Islam mainly happened through two routes: from the southeast following an established path to Canton and from the northwest through the Silk Road.[13] Sa'ad ibn Abi Waqqas, along with the Sahaba Suhayla Abuarja and Hassan ibn Thabit, and the Tabi'een Uwais al-Qarani, returned to China from Arabia in 637 CE by the Yunan-Manipur-Chittagong route, then reached Arabia by sea.[14] Some sources date the introduction of Islam in China to 650 CE, the third sojourn of Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas,[15] when he was sent as an official envoy to Emperor Gaozong during Caliph Uthman's reign.[16] Emperor Gaozong, the Tang emperor who is said to have received the envoy then ordered the construction of the Memorial mosque in Canton in memory of Muhammad, which was the first mosque in the country.[15][17] While modern secular historians tend to say that there is no evidence that Waqqās himself ever came to China,[17] they do believe that Muslim diplomats and merchants came to Tang China within a few decades from the beginning of the Muslim Era.[17]

The early Tang dynasty had a cosmopolitan culture, with intensive contacts with Central Asia and significant communities of (originally non-Muslim) Central and Western Asian merchants resident in Chinese cities, which helped the introduction of Islam.[17] The first major Muslim settlements in China consisted of Arab and Persian merchants,[18] with comparatively well-established, even if somewhat segregated, mercantile Muslim communities existing in the port cities of Guangzhou, Quanzhou and Hangzhou on China's southeastern seaboard, as well as in the interior centers such as Chang'an, Kaifeng and Yangzhou during the Tang and especially Song eras.[19] It is recorded in 758 that Arab and Persian pirates who probably had their base in a port on the island of Hainan, sacked Guangzhou, causing some of the trade to divert to Northern Vietnam and the Chaozhou area, near the Fujian border. In 760 in Yangzhou, troops targeted and killed Arab and Persian merchants for their wealth in the Yangzhou massacre.[20][21] Around 879, rebels killed about 120,000–200,000 mostly Arab and Persian foreigners in Guanzhou in the Guangzhou massacre. It is believed that the profile of Muslims as traders led to the government ignoring Muslims in the 845 Great Anti-Buddhist Persecution, even though it virtually extinguished Zoroastrianism and Nestorian Christianity in China.[22][23][24]

In 751, the Abbasid empire defeated the Tang Dynasty at the Battle of Talas, marking the end of Tang westward expansion and resulted in Muslim control of Transoxiana for the next 400 years. However, Arab control ended in 821 when the Persian Tahirid dynasty took power, then Turks took power in 977 under the Ghaznavids and Muslim control ended in 1124 when the non-Muslim Qara Khitai conquered Transoxania.

Song dynasty

By the time of the Song dynasty, Muslims had come to play a major role in the import/export industry.[15][19] The office of Director General of Shipping was consistently held by a Muslim during this period.[25] In 1070, the Song emperor Shenzong invited 5,300 Muslim men from Bukhara, to settle in Song China in order to create a buffer zone between the Song and the Liao dynasties in the northeast. Later on, these men settled between the Sung capital of Kaifeng and Yenching (modern day Beijing).[26] They were led by Prince Amir Sayyid "Su-fei-er"[27] (his Chinese name), who was called the "father" of the Muslim community in China. Prior to him, Islam was named by the Tang and Song Chinese as Dashi fa ("law of the Arabs").[28] He renamed it to Huihui Jiao ("the Religion of the Huihui").[29]

It is reported that "in 1080, another group of more than 10,000 Arab men and women are said to have arrived in China on horsebacks to join Sofeier. These people settled in all provinces".[27] Pu Shougeng, a Muslim official who worked for the Song but defected to the Yuan, stands out in his work to help the Yuan conquer Southern China, the last outpost of Song power. In 1276, Song loyalists launched a resistance to Mongol efforts to take over Fuzhou. The Yuanshih (Yuan dynasty official history) records that Pu Shougeng, as former Song official, "abandoned the Song cause and rejected the emperor...by the end of the year, Quanzhou submitted to the Mongols."In abandoning the Song cause, Pu Shougeng mobilized troops from the community of foreign residents, who massacred relatives of the Song emperor and Song loyalists who were living in the city. Other members of the Song royal family escaped to other parts of Fujian and Guangdong and survived to the present. Pu Shougeng and his troops acted without the help of the Mongol army and he defected after Song general Zhang Shijie seized his ships and properties after Pu refused to lend Zhang ships for the war. Pu Shougeng himself was lavishly rewarded by the Mongols. He was appointed military commissioner for Fujian and Guangdong. However, towards the end of the Yuan dynasty, the Yuan Mongols turned against Pu Shougeng's family and the Muslims and slaughtered Pu Shougeng's descendants in the Ispah rebellion. Mosques and other buildings with foreign architecture were almost all destroyed and the Yuan imperial soldiers killed most of the descendants of Pu Shougeng and horrifically mutilated their corpses.[30]

Tombs of Imams

On the foothills of Mount Lingshan are the tombs of two of the four companions that Prophet Muhammad sent eastwards to preach Islam. Known as the 'Holy Tombs', they house the companions Sa-Ke-Zu and Wu-Ko-Shun. The other two companions went to Guangzhou and Yangzhou.[31] The Imam Asim, is said to have been one of the first Islamic missionaries in China. He was a man who lived in c. 1000 CE in Hotan. The shrine site includes the reputed tomb of the Imam, a mosque, and several related tombs.[32] There is also a mazaar of Imam Jafar Sadiq.[33]

Yuan dynasty

Hamada Hagras recorded: "With China unified under the Yuan dynasty, traders were free to traverse China freely. The Mongols were aware of the impact of trade and were keen to improve Chinese infrastructure to ensure the flow of goods. One major project was the repair and inauguration of Chinese Grand Canal that linked Khanbaliq (modern-day Beijing) in the north with Hangzhou in the south-east on the coast. Ningbo's location on the central coast and at the end of the Canal was the motive of the mercantile development of the east coast of China. The Grand Canal was an important station that helped the spread of Islam in the cities of China's east coast; Muslim merchants could now easily travel to the north along the canal. This made the banks of the channel regions become key areas for the spread of Islam eastern China."[34]

During the Mongol-founded Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), large numbers of Muslims settled in China. The Mongols, a minority in China, gave foreign immigrants, such as Christians, Muslims and Jews from West Asia an elevated status over the native Han Chinese as part of their governing strategy, thus giving Muslims a heavy influence. Mongols recruited and forcibly relocated hundreds of thousands of Muslim immigrants from Western and Central Asia to help them administer their rapidly expanding empire.[7] The Mongols used Arab, Persian and Buddhist Uyghur administrators, generically known as semu [色目] ("various eye color"),[35] to act as officers of taxation and finance. Muslims headed many corporations in China in the early Yuan period.[36] Muslim scholars were brought to work on calendar making and astronomy. The architect Yeheidie'erding (Amir al-Din) learned from Han architecture to help design the construction of the capital of the Yuan Dynasty, Dadu (also known as Khanbaliq or present-day Beijing).[37]

The term Hui originated from the Mandarin "Huihui," a term first used in the Yuan dynasty to describe Arab, Persian and Central Asian residents in China.[17] Many of the Muslim traders and soldiers eventually settled down in China and married Chinese wives. This gave rise to the Hui Muslims, meaning Chinese-speaking Muslims.[13]

A rich merchant from the Ma'bar Sultanate, Abu Ali (P'aehali) 孛哈里 (or 布哈爾, Buhaer), was associated closely with the Ma'bar royal family. After falling out with them, he moved to Yuan dynasty China and received a Korean woman as his wife and a job from the Yuan emperor; the woman was formerly the wife of Sangha (Chinese: 桑哥), and her father was Ch'ae In'gyu (Chinese: 蔡仁揆; Korean: 채송년) during the reign of Chungnyeol of Goryeo, recorded in the Dongguk Tonggam, Goryeosa and Zhong'anji (Chinese: 中俺集) of Liu Mengyan (留夢炎).[38][39]

Genghis Khan and his successors forbade Islamic practices like halal butchering, as well as other restrictions. Muslims had to slaughter sheep in secret.[40] Genghis Khan outright called Muslims and Jews "slaves", and demanded that they follow the Mongol method of eating rather than the halal method. Circumcision was also forbidden. Jews were affected by these laws and forbidden by the Mongols to eat Kosher.[41] Towards the end of the Yuan dynasty, corruption and persecution became so severe that Muslim generals joined the Han Chinese in rebelling against the Mongols. The founder of the Ming dynasty, Hongwu Emperor, led Muslim generals like Lan Yu against the Mongols, whom they defeated in combat. Some Muslim communities had a name in Chinese which meant "barracks" or "thanks," which many Hui Muslims claim comes from the gratitude which Chinese people have towards them for their role in defeating the Mongols.[42]

Among all the [subject] alien peoples only the Hui-hui say "we do not eat Mongol food". [Cinggis Qa'an replied:] "By the aid of heaven we have pacified you; you are our slaves. Yet you do not eat our food or drink. How can this be right?" He thereupon made them eat. "If you slaughter sheep, you will be considered guilty of a crime." He issued a regulation to that effect ... [In 1279/1280 under Qubilai] all the Muslims say: "if someone else slaughters [the animal] we do not eat". Because the poor people are upset by this, from now on, Musuluman [Muslim] Huihui and Zhuhu [Jewish] Huihui, no matter who kills [the animal] will eat [it] and must cease slaughtering sheep themselves, and cease the rite of circumcision.[43]

Ispah rebellion

The Muslims in the semu class also revolted against the Yuan dynasty in the Ispah Rebellion, but the rebellion was crushed and the Muslims were massacred by the Yuan loyalist commander Chen Youding.

The Yuan dynasty passed anti-Muslim and anti-Semu laws and got rid of Semu privileges near the end of the Yuan dynasty period. In 1328 the Qadi (Muslim headmen) were abolished after being limited in 1311. Also, in 1340 all marriages had to follow Confucian rules, this was in contrast to a law in 1329, where all foreign holy men and clerics (including Muslims) no longer were exempted from the tax. In the middle of the 14th century this caused Muslims to incite rebellion against Yuan rule and joined rebel groups. In 1357–1367 the Yisibaxi Muslim Persian garrison started the Ispah rebellion against the Yuan dynasty in Quanzhou and southern Fujian. Persian merchants Amid ud-Din (Amiliding) and Saif ud-Din (Saifuding) led the revolt. A Persian official, Yawuna assassinated both of them in 1362 and took control of the Muslim rebel forces. The rebels moved north but were defeated at Fuzhou. Yuan provincial loyalist forces from Fuzhou defeated the Muslim rebels in 1367 after a Muslim rebel officer named Jin Ji defected from Yawuna.[44][45]

Yuan Massacres of Persians and Arabs

The aftermath of the Ispah rebellion saw Yuan general Chen Youding slaughter Muslims in Quanzhou. One of Sayyid Ajall Shams al-Din Omar's descendants, fled to Quanzhou to avoid the violence of the Ispah rebellion. The rebellion led to many Muslims fleeing to Java and other places in Southeast Asia to escape the massacres. Ma Huan reported that Gresik was ruled by a person from China's Guangdong province and it had a thousand Chinese families who moved there in the 14th century. Like most Muslims form China, Wali Sanga Sunan Giri was a Hanafi according to Stamford Raffles.[46][47] Many Persian and Arab merchants fled abroad by ships, while another small group that adopted Chinese culture were expelled or took refuge in Quanzhou's mosques. The genealogies of Muslim families which survived the transition are the main source of information on the rebellion. Ibn Battuta had visited Quanzhou's large multi-ethnic Muslim community before the Ispah rebellion in 1357.

The Muslim Rongshan Li family, (a survivor of the violence during the Yuan-Ming transition period) wrote about their ancestor Li Lu during the rebellion, where they had to survive by using his private stores from his trading business to feed hungry people during the rebellion and used his connections to keep safe. They also mentioned that "great families were scattered from their homes, which were burned by the soldiers, and few genealogies survived".

After the Persian garrison fell and the rebellion was crushed, a slaughter of the Pu family and Muslims occurred in the city: All of the West Asian immigrants were annihilated, with a number of foreigners with large noses mistakenly killed while for three days the gates were closed and the executions were carried out. The corpses of the Pus were all stripped naked, their faces to the west. ... They were all judged according to the "five mutilating punishments" and then executed with their carcasses throwing into pig troughs. This was in revenge for their murder and rebellion in the Yuan.[48] The Ming takeover after the end of the Persian garrison meant that the diaspora of incoming Muslims ended.

The Muslim community in Quanzhou became a target of the people's anger. In the streets there was widescale slaughter of "big nosed" westerners and Muslims as recorded in a genealogical account of a Muslim family. The era of Quanzhou as an international trading port of Asia ended as did the role of Muslims as merchant diaspora in Quanzhou. Some Muslims fled while others tried to hide despite the Ming emperors issuing laws that tolerated Islam in 1368 and 1407.[49][50]

The Nine Wali Sanga who converted Java to Islam had Chinese names and originated from Chinese speaking Quanzhou Muslims who fled there in the 14th century around 1368. However, Suharto banned this discussion in 1964.[51]

Early Ming period

The Ming policy towards the Islamic religion was tolerant, while their racial policy towards ethnic minorities was of integration through forced marriage. Muslims were allowed to practice Islam, but if they were members of other ethnic groups they were required by law to intermarry, so Hui had to marry Han since they were different ethnic groups, with the Han often converting to Islam.

Integration was mandated through intermarriage by Ming law, ethnic minorities had to marry people of other ethnic groups.[52] Marriage between upper class Han Chinese and Hui Muslims was low, since upper class Han Chinese men would both refuse to marry Muslim women, and forbid their daughters from marrying Muslim men, since they did not want to convert due to their upper class status. Only low and mean status Han Chinese men would convert if they wanted to marry a Hui woman. Ming law allowed Han Chinese men and women to not have to marry Hui, and only marry each other, while Hui men and women were required to marry a spouse not of their race.[53][54][55] Both Mongol and Central Asian Semu Muslim women and men of both sexes were required by the Ming Code to marry Han Chinese when Emperor Hongwu passed the law in Article 122.[56][57][58]

In 1368 Quanzhou came under Ming control and the atmosphere calmed down for the Muslims. The Ming Yongle emperor issued decrees of protection from individuals and officials in mosques and his father, Hongwu had support from Muslim generals so he showed tolerance to them. The Ming passed some laws saying Muslims could not use Chinese surnames. The Muslim Li family mentioned there were debates over the teaching between Confucianism (such as learning the Shijing and Shangshu) and practicing Islam. Hongwu passed laws that restricted maritime trade in Quanzhou to Ryukyu. Guangzhou was to monopolize the south sea trade in the 1370s and 1403–1474 after getting rid of the Office of Maritime Trade altogether in 1370. Up to the late 16th century, private trade was banned.[59]

Salars

After the Oghuz Turkmen Salars moved from Samarkand in Central Asia to Xunhua, Qinghai during the early Ming dynasty, living on both banks of the Yellow river. They converted and married Tibetan women.[60] The Salars practiced the same Gedimu (Gedem) variant of Sunni Islam as the Hui people and adopted several of their practices such as the Hui Islamic education system of Jingtang Jiaoyu. The Hui introduced new Naqshbandi Sufi orders to the Salars which led to sectarian violence involving Qing soldiers and the Salar and Hui Sufis. Ma Laichi brought the Khafiyya Naqshbandi order to the Salars and the Salars followed the Flowered mosque order (花寺門宦) of the Khafiyya.[61] According to legend, the marriages between Tibetan women and Salar men came after a compromise.

It is rare for a Salar to marry ethnic Hans but Salars continue to use Han surnames.[62][63] Salars almost exclusively took non-Salar women as wives, while Salar women do not marry non-Salar men (except for Hui men).[64] Marriage ceremonies, funerals, birth rites and prayer were shared by both Salar and Hui as they intermarried and shared the same religion. The Salar language and culture however was highly impacted in the 14th to 16th centuries by marriage with Mongol and Tibetan non-Muslims with many loanwords and grammatical influence into the Salar language. Some Salars were even multilingual, speaking Mongol, Chinese and Tibetan as they traded extensively during the Ming, Qing and early 20th century periods around Ningxia and Gansu.[65]

The Salars also converted the Kargan Tibetans, who came from Samarkand to China.[66][67] In eastern Qinghai and Gansu there were cases of Tibetan women who stayed in their Buddhist Lamaist religion while marrying Chinese Muslim men and they would have different sons who would be Buddhist and Muslims.[68]

Middle to late Ming period

During the following Ming dynasty, Muslims continued to be influential around government circles. Six of Ming dynasty founder Hongwu Emperor's most trusted generals are said to have been Muslim, including Lan Yu who, in 1388, led a strong imperial Ming army out of the Great Wall and won a decisive victory over the Mongols in Mongolia, effectively ending the Mongol dream to re-conquer China. During the war fighting the Mongols, among the Ming Emperor Zhu Yuanzhang's armies was the Hui Muslim Feng Sheng.[69] Zhu Yuanzhang also wrote a praise of Islam, The Hundred-word Eulogy. It was recorded that "His Majesty ordered to have mosques built in Xijing and Nanjing [the capital cities], and in southern Yunnan, Fujian and Guangdong. His Majesty also personally wrote baizizan [a eulogy] in praise of the Prophet's virtues."[70] Additionally, the Yongle Emperor hired Zheng He, perhaps the most famous Chinese of Muslim birth although at least in later life not a Muslim himself, to lead seven expeditions to the Indian Ocean from 1405 and 1433. However, during the Ming Dynasty, new immigration to China from Muslim countries was restricted in an increasingly isolationist nation. The Muslims in China who were descended from earlier immigration began to assimilate by speaking Chinese and by adopting Chinese names and culture. Mosque architecture began to follow traditional Chinese architecture. This era, sometimes considered the Golden Age of Islam in China,[71] also saw Nanjing become an important center of Islamic study.[72]

Around 1376 the 30-year-old Chinese merchant Lin Nu visited Ormuz in Persia, converted to Islam and married a Semu girl ("娶色目女") (either a Persian or an Arab girl) and brought her back to Quanzhou in Fujian.[73]

Muslims in Ming dynasty Beijing were given relative freedom by the Chinese, with no restrictions placed on their religious practices or freedom of worship and being normal citizens in Beijing. In contrast to the freedom granted to Muslims, followers of Tibetan Buddhism and Catholicism suffered from restrictions and censure in Beijing.[74]

The Hongwu Emperor decreed the building of multiple mosques throughout China in many locations. A Nanjing mosque was built by the Xuande Emperor.[75] Weizhou Grand Mosque, considered as one of the most beautiful, was constructed during the Ming dynasty.[76][77][78][79]

An anti pig slaughter edict led to speculation that the Zhengde Emperor adopted Islam due to his use of Muslim eunuchs who commissioned the production of porcelain with Persian and Arabic inscriptions.[80] Central Asian women were provided to the Zhengde Emperor by a Muslim guard and Sayyid Hussein from Hami.[81] The guard was Yu Yung and the women were Uyghur. Muslim eunuchs contributed money in 1496 in repairing Niujie Mosque.[82] It is unknown who really was behind the anti-pig slaughter edict.[83] The speculation of him becoming a Muslim is remembered alongside his excessive and debauched behavior along with his concubines of foreign origin.[84][85] Muslim Central Asian girls were favored by Zhengde like how Korean girls were favored by Xuande.[86] A Uyghur concubine was kept by Zhengde.[87] Foreign origin Uyghur and Mongol women were favored by the Zhengde emperor.[88] Tatar (Mongol) and Central Asian women were bedded by Zhengde.[89] Zhengde received Central Asian Muslim Semu women from his Muslim guard Yu Yong, and Ni'ergan was the name of one of his Muslim concubines.[90][91]

When the Qing dynasty invaded the Ming dynasty in 1644, Muslim Ming loyalists led by Muslim leaders Milayin, Ding Guodong and Ma Shouying led a revolt in 1646 against the Qing during the Milayin rebellion in order to drive the Qing out and restore the Ming Prince of Yanchang Zhu Shichuan to the throne as the emperor. The Muslim Ming loyalists were crushed by the Qing with 100,000 of them, including Milayin and Ding Guodong killed.

Qing dynasty

%252C_1772..jpg.webp)

The Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1636–1912) witnessed multiple revolts, with several major revolts headed by Muslim leaders. During the Qing dynasty's conquest of the Ming dynasty from 1644; Muslim Ming loyalists in Gansu led by Muslim leaders Milayin[92] and Ding Guodong led a revolt in 1646 against the Qing during the Milayin rebellion in order to drive the Qing out and restore the Ming Prince Zhu Shichuan to the throne as emperor.[93] The Muslim Ming loyalists were supported by Hami's Sultan Sa'id Baba and his son Prince Turumtay.[94][95][96] The Muslim Ming loyalists were joined by Tibetan and Han peoples in the revolt.[97] After fierce fighting, and negotiations, a peace agreement was agreed in 1649, where Milayan and Ding nominally pledged allegiance to the Qing and were given ranks as members of the military.[98] When the other Ming loyalists in southern China resumed hostilities, the Qing were forced to withdraw their forces from Gansu to fight them, Milayan and Ding once again took up arms and rebelled against the Qing.[99] The Muslim Ming loyalists were then crushed by the Qing with 100,000 of them, including Milayin, Ding Guodong, and Turumtay killed in battle.

The Confucian Hui Muslim scholar Ma Zhu (1640–1710) served with the Southern Ming loyalists against the Qing.[100] Zhu Yu'ai (the Ming Prince Gui) was accompanied by Hui refugees when he fled from Huguang to the Burmese border in Yunnan and as a mark of their defiance against the Qing and loyalty to the Ming, they changed their surname to Ming.[101]

In Guangzhou, the national monuments known as "The Muslim's Loyal Trio" are the tombs of Ming loyalist Muslims who were martyred while fighting in battle against the Qing during the Ming–Qing transition period in Guangzhou.[102] The Ming Muslim loyalists were called Jiaomen sanzhong "Three defenders of the faith".[101]

The Kangxi Emperor incited anti-Muslim sentiment among the Mongols of Qinghai (Kokonor) in order to gain support against the Dzungar Oirat Mongol leader Galdan. Kangxi claimed that Chinese Muslims inside China such as Turkic Muslims in Qinghai (Kokonor) were plotting with Galdan, who he falsely claimed converted to Islam. Kangxi falsely claimed that Galdan had spurned and turned his back on Buddhism and the Dalai Lama and that he was plotting to install a Muslim as ruler of China after invading it in a conspiracy with Chinese Muslims. The Kangxi Emperor also distrusted Muslims of Turfan and Hami.[103]

In the Jahriyya revolt sectarian violence between two suborders of the Naqshbandi Sufis, the Jahriyya Sufi Muslims and their rivals, the Khafiyya Sufi Muslims, led to a Jahriyya Sufi Muslim rebellion which the Qing dynasty crushed with the help of the Khafiyya Sufi Muslims.[104]

The Ush rebellion in 1765 by Uyghurs against the Manchus occurred after Uyghur women were gang raped by the servants and son of Manchu official Su-cheng.[105][106][107] It was said that Ush Muslims had long wanted to sleep on [Sucheng and son's] hides and eat their flesh.[108] The Manchu Emperor ordered that the Uyghur rebel town be massacred, the Qing forces enslaved all the Uyghur children and women and slaughtered the Uyghur men.[109]

The invasion by Jahangir Khoja was preceded by another Manchu official, Binjing who raped a Muslim daughter of the Kokan aqsaqal from 1818 to 1820. The Qing sought to cover up the rape of Uyghur women.[110] Jahangir Khoja was then sliced to death (lingchi) in 1828 by the Manchus for leading the rebellion against the Qing.

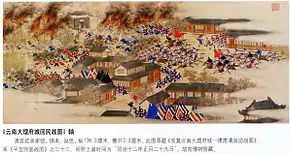

The Manchu official Shuxing'a started an anti-Muslim massacre which led to the Panthay Rebellion (1856–1873). Shuxing'a developed a deep hatred of Muslims after an incident where he was stripped naked and nearly lynched by a mob of Muslims. He ordered a lingchi unto several Muslim rebels.[111][112]

The Muslim revolt in the northwest occurred due to violent and bloody infighting between Muslim groups (Gedimu, Khafiya and Jahriyya). The rebellion in Yunnan occurred because of repression by Qing officials, resulting in bloody Hui rebellions, most notably the Dungan revolt, which occurred mostly in Xinjiang, Shensi and Gansu, from 1862 to 1877. The Manchu government ordered the execution of several million rebels in the Dungan revolt.[113] The Hui Muslim population of Beijing was unaffected from the Muslim rebels during the Dungan revolt.[114]

Elisabeth Allès wrote that the relationship between Hui Muslim and Han peoples continued normally in the Henan area, with no ramifications or consequences from the Muslim rebellions of other areas. Allès wrote "the major Muslim revolts in the mid-19th century which involved the Hui in Shaanxi, Gansu and Yunnan, as well as the Uyghurs in Xinjiang, do not seem to have had any direct effect on this region of the central plain."[115]

However, many Muslims like Ma Zhan'ao, Ma Anliang, Dong Fuxiang, Ma Qianling and Ma Julung defected to the Qing dynasty and helped the Qing General Zuo Zongtang exterminate the Muslim rebels. These Muslim generals belonged to the Khafiya sect, and they abetted in the Qing massacre of Jahariyya rebels. Zuo relocated the Han from Hezhou as a reward for the Muslims for helping the Qing to kill other Muslim rebels. In 1895, another Dungan Revolt broke out, and loyalist Muslims such as Dong Fuxiang, Ma Anliang, Ma Guoliang, Ma Fulu and Ma Fuxiang suppressed and massacred the rebel Muslims led by Ma Dahan, Ma Yonglin and Ma Wanfu. The Muslim army, Kansu Braves, led by General Dong Fuxiang fought for the Qing dynasty against the foreigners during the Boxer Rebellion. They included well known generals like Ma Anliang, Ma Fulu and Ma Fuxiang.

In Yunnan, the Qing armies exterminated only the Muslims who had rebelled and spared Muslims who took no part in the uprising.[116]

Uyghurs in Turfan and Hami and their leaders like Emin Khoja allied with the Qing against Uyghurs in Altishahr. The Qing dynasty enfeoffed (granted freehold property in exchange for pledged service) the rulers of Turpan, in eastern present-day Xinjiang and Hami (Kumul) as autonomous princes, while the rest of the Uyghurs in Altishahr (the Tarim Basin) were ruled by Begs.[117]: 31 Uyghurs from Turpan and Hami were appointed by China as officials to rule over Uyghurs in the Tarim Basin.

In addition to sending Han exiles convicted of crimes to Xinjiang to be slaves of Banner garrisons there, the Qing also practiced reverse exile, exiling Inner Asian (Mongol, Russian and Muslim criminals from Mongolia and Inner Asia) to China proper where they would serve as slaves in Han Banner garrisons in Guangzhou. Russian, Oirats and Muslims such as Yakov and Dmitri were exiled to the Han banner garrison in Guangzhou.[118] In the 1780s after the Muslim rebellion in Gansu started by Zhang Wenqing (張文慶) was defeated, Muslims like Ma Jinlu (馬進祿) were exiled to the Han Banner garrison in Guangzhou to become slaves to Han Banner officers.[119] The Qing code regulating Mongols in Mongolia sentenced Mongol criminals to exile and to become slaves to Han bannermen in Han Banner garrisons in China proper.[120]

Republic of China

In the 1900s decade, its estimated that there were 20 million Muslims in China proper (that is, China excluding the regions of Mongolia and Xinjiang).[121][122][123][124] Of these, almost half resided in Gansu, over a third in Shaanxi (as defined at that time) and the rest in Yunnan.[125]

The Hui Muslim community was divided in its support for the 1911 Xinhai Revolution. The Hui of Shaanxi supported the revolutionaries while the Hui of Gansu supported the Qing Empire. The Hui of Xi'an joined Han revolutionaries in slaughtering the entire 20,000 Manchu population of Xi'an.[126][127][128] The native Hui of Gansu led by general Ma Anliang sided with the Qing and prepared to attack the anti-Qing revolutionaries of Xi'an. Only some wealthy ransomed Manchus and females survived. Wealthy Han seized Manchu girls to become their slaves[129] and poor Han troops seized young Manchu women to be their wives.[130] Young pretty Manchu girls were also seized by Hui of Xi'an during the massacre and brought up as Muslims.[131]

The Qing dynasty fell in 1912, and the Republic of China was established by Sun Yat-sen, who immediately proclaimed the equality of the Han, Hui, Manchu, Mongol, and Tibetan peoples. This led to some improvement in relations between these different peoples. The end of dynasty also marked an increase in Sino-foreign interactions. This led to increased contact between Muslim minorities in China and the Islamic states of the Middle East. In 1912, the Chinese Muslim Federation was formed in the capital Nanjing. Similar organization formed in Beijing (1912), Shanghai (1925) and Jinan (1934).[132]

During the rule of the Kuomintang party, Muslim warlords (such as the Ma clique) were appointed as military governors of the provinces of Qinghai, Gansu and Ningxia. Bai Chongxi was a Muslim General and Defence Minister of China during this time.

During the Second Sino-Japanese war, the Japanese destroyed 220 mosques and killed countless Hui by April 1941.[133] The Hui of Dachang was subjected to slaughter by the Japanese.[69] During the Rape of Nanking, the mosques contained dead bodies after the Japanese slaughters. According to Wan Lei, "statistics showed that the Japanese destroyed 220 mosques and killed countless Hui people by April 1941." The Japanese followed a policy of economic oppression which involved the destruction of mosques and Hui communities and made many Hui jobless and homeless. Another policy was one of deliberate humiliation. This included soldiers smearing mosques with pork fat, forcing Hui to butcher pigs to feed the soldiers, and forcing girls to serve as sex slaves. Hui cemeteries were destroyed for military reasons.[134] Many Hui fought in the war against Japan.

In 1937, during the Battle of Beiping–Tianjin, the Chinese government received a telegram from Muslim General Ma Bufang that he was prepared to fight the Japanese.[137] Immediately after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident, Ma Bufang arranged for a cavalry division under the Muslim General Ma Biao to be sent east to battle the Japanese.[138] Ethnic Turkic Salar Muslims made up the majority of the first cavalry division which was sent by Ma Bufang.[139]

By 1939, at least 33 Hui Muslims had studied at Cairo's Al-Azhar University. Before the Sino-Japanese War of 1937, there existed more than a hundred known Muslim periodicals. Thirty journals were published between 1911 and 1937. Although the Linxia region remained a center of religious activities, many Muslim cultural activities had shifted to Beijing.[140] National organizations like the Chinese Muslim Association were established for Muslims. Muslims served extensively in the National Revolutionary Army and reached positions of importance, like General Bai Chongxi, who became Defence Minister of the Republic of China.

In the Kuomintang Islamic insurgency, Muslim Kuomintang National Revolutionary Army forces in Northwest China, in Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia, Xinjiang, as well as Yunnan, continued an unsuccessful insurgency against the communists from 1950 to 1958, after the general civil war was over. Muslims affiliated with the Kuomintang also moved to Taiwan within this time.

People's Republic of China

When the People's Republic of China was established in 1949, Muslims, along with all other religions in China, suffered repression especially during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Islam, like all religions including traditional Chinese religion, was persecuted by the Red Guards who were encouraged to smash the Four Olds. Numerous places of worship, including mosques, were attacked.[141]

In 1975, in what would be known as the Shadian incident, there was an uprising among Hui Muslims and became the only large scale ethnic rebellion during the Cultural Revolution.[142] In crushing the rebellion, the PLA massacred 1,600 Hui[142] with MIG fighter jets used to fire rockets onto the village. Following the fall of the Gang of Four, apologies and reparations were made.[143] During that time, the government also constantly accused Muslims and other religious groups of holding "superstitious beliefs" and promoting "anti-socialist trends".[144] The government began to relax its policies towards Muslims in 1978.[145]

After the advent of Deng Xiaoping in 1979, Muslims enjoyed a period of liberalisation. New legislation gave all minorities the freedom to use their own spoken and written languages, to develop their own culture and education and to practice their religion.[146] More Chinese Muslims than ever before were allowed to go on pilgrimage to Mecca.[147]

There is an ethnic separatist movement among the Uyghur minority, who are a Turkic people with their own language. Uyghur separatists are intent on establishing their own state, which existed for a few years in the 1930s and as a Soviet Communist puppet state, the Second East Turkestan Republic in 1944–1950. The Soviet Union supported Uyghur separatists against China during the Sino-Soviet split. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, China feared potential separatist goals of the Muslim majority in Xinjiang.

In the past, celebrating at religious functions and going on Hajj to Mecca was encouraged by the Chinese government for Uyghur members of the Communist party. From 1979 to 1989, 350 mosques were built in Turpan.[148] Whereas 30 years later, the government was building "re-education" camps for interning Muslims without charge in Turpan.[149]

In 1989, China banned a book titled "Xing Fengsu" ("Sexual Customs") which insulted Islam and placed its authors under arrest after protests in Lanzhou and Beijing by the Hui, during which the police provided protection to the Hui protestors and the government organized public burnings of the book.[150] Hui Muslim protestors who violently rioted by vandalizing property during the protests against the book were let off by the Chinese government and went unpunished while Uyghur protestors were imprisoned.[151]

Since the 1980s, Islamic private schools (Sino-Arabic schools (中阿學校)) have been supported and permitted by the Chinese government in Muslim areas, only specifically excluding Xinjiang from allowing these schools because of separatist sentiment there.[152] After secondary education is completed, Hui students are permitted to embark on religious studies under an Imam.[153][154][155]

21st century

In 2007, anticipating the coming "Year of the Pig" in the Chinese calendar, depictions of pigs were banned from CCTV "to avoid conflicts with Muslim minorities".[156] This is believed to refer to China's population of 20 million Muslims (to whom pigs are considered "unclean"). Hui Muslims enjoy freedoms such as practising their religion, building mosques at which their children attend, while Uyghurs in Xinjiang experience more strict controls.[157]

There are about 24,400 mosques in Xinjiang, an average of one mosque for every 530 Muslims, which is higher than the number of churches per Christian person in England.[158][159]

In March 2014, the Chinese media estimated that there were around 300 Chinese Muslims active in ISIS territories.[160] The Chinese government stated in May 2015 that it would not tolerate any form of terrorism and would work to "combat terrorist forces, including ETIM, [to] safeguard global peace, security and stability."[161]

Muslims were reported in 2015 to have been featured as hosts and directors on the Chinese New Year Gala.[162]

In response to the 2015 Charlie Hebdo shooting, Chinese state-run media attacked Charlie Hebdo for publishing the cartoons insulting Muhammad, with the state-run Xinhua advocating limiting freedom of speech, while the Chinese Communist Party-owned tabloid Global Times said the attack was "payback" for what it characterised as Western colonialism and accusing Charlie Hebdo of trying to incite a clash of civilizations.[163]

In the five years to 2017, a 306% rise in criminal arrests was seen in Xinjiang and the arrests there accounted for 21% of the national total, despite the region contributing just 1.5% of the population. The increase was seen as driven by the government's "Strike Hard" campaign. In 2017, driven by a 92% in security spending there that year, an estimated 227,882 criminal arrests were made in Xinjiang.[164][165]

In August 2018, the authorities were vigorously pursuing the suppression of mosques, including their widespread destruction,[166] over Muslim protests.[167] Also at that time, the growing of long beards and the wearing of veils or Islamic robes for Uyghurs, were banned. All vehicle owners were required to install GPS tracking devices.[165]

NPR reported that from 2018 to 2020 the repression of non-Uyghur Muslims intensified. Imams have been restricted to practicing within the region their household is registered in. Prior to these restrictions China had hundreds of itinerant Imams. During this period the Chinese government forced nearly all mosques in Ningxia and Henan to remove their domes and Arabic script. In 2018 new language restrictions forced hundreds of Arabic schools in Ningxia and Zhengzhou to close.[168]

A 2019 paper from the Gallatin School of Individualized Study interviewed Hui Muslims in Xining, Lanzhou, and Yinchuan and found that none saw the recent policies or government as detrimental to their religious lives. Although some foresaw a future of Islam in China much different than what they were used to, they did not seem to worry if it was good or bad as long as they had access to mosques, halal food and security.[169] Arabic calligraphy was also reported by The Hindu in 2019 to be commonplace at the Linxia Hui Autonomous Prefecture.[170] The National reported in the same year of a female ahong in Xi'an teaching those in her mosque how to pray and read the Quran in Arabic.[171]

Chinese Muslims reportedly celebrated Ramadan on 2021 in the cities of Shanghai[172] and Beijing.[173] The Star reported in the same year that Uyghurs in Xinjiang made prayers for Aidilfitri.[174]

Uyghur repression

By 2013, repression of Uyghurs extended to disappeared dissidents and imposing of life imprisonment sentences on academics for promoting Uyghur social interactions.[175] Hui Muslims who are employed by the state are allowed to fast during Ramadan unlike Uyghurs in the same positions, the number of Huí going on Hajj was reported to be expanding in 2014 and Hui women are allowed to wear veils, while Uyghur women are discouraged from wearing them. Uyghurs find it difficult to get passports to go on Hajj.[176][177] In July 2014, Reuters reported that Uyghurs in Shanghai could practise their religion, with some expressing more freedom there than in Xinjiang.[178]

The Associated Press (AP) reported in late November 2018 that Uyghur families were required to allow local government officials to live in their homes as "relatives" in a "Pair Up and Become Family" campaign. While the official was living in a home, the residents were closely watched and not allowed to pray or wear religious clothing. Authorities said that the program was voluntary but Muslims who were interviewed by AP expressed concern that refusal to cooperate would lead to serious repercussions.[179]

Tibetan-Muslim sectarian violence

In Tibet, the majority of Muslims are Hui people. Hatred between Tibetans and Muslims stems from events during the Muslim warlord Ma Bufang's rule in Qinghai such as the Ngolok rebellions (1917–1949) and the Sino-Tibetan War. Violence subsided after 1949 under Communist Party repression but reignited as strictures were relaxed.

Riots broke out in March 2008 between Muslims and Tibetans over incidents such as suspected human bones in and deliberate contamination of soups served in Muslim-owned establishments and overpricing of balloons by Muslim vendors. Tibetans attacked Muslim restaurants. Fires set by Tibetans resulted in Muslim deaths and riots. The Tibetan exile community sought to suppress reports reaching the international community, fearing damage to the cause of Tibetan autonomy and fueling Hui Muslim support of government repression of Tibetans generally.[180][181]: 1–2 In addition, Chinese-speaking Hui have problems with Tibetan Hui (the Tibetan speaking Kache minority of Muslims).[182] The main mosque in Lhasa was burned down by Tibetans during the unrest.[183]

The majority of Tibetans viewed the wars against Iraq and Afghanistan after 9/11 positively and it had the effect of galvanizing anti-Muslim attitudes among Tibetans and resulted in an anti-Muslim boycott against Muslim owned businesses.[181]: 17 Tibetan Buddhists propagate a false libel that Muslims cremate their Imams and use the ashes to convert Tibetans to Islam by making Tibetans inhale the ashes.[181]: 19

Internment camps and restrictions on religious freedom

The Xinjiang re-education camps are officially called "Vocational Education and Training Centers" by the Chinese government.[184] The camps have been operated by the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Regional government since 2014. However, the efforts of the camps strongly intensified after a change of head for the region. Alongside the Uyghurs, other Muslim minorities have also been reported to be held in these re-education camps. As of 2019, 23 nations in the United Nations have signed a letter condemning China for the camps and asking them to close them.[185]

In May 2018, western news media reported that hundreds of thousands of Muslims were being detained in massive extrajudicial internment camps in western Xinjiang.[186] These were called s "re-education" camps and later, "vocational training centres" by the government, intended for the "rehabilitation and redemption" to combat terrorism and religious extremism.[187][164][188][189][190]

In August 2018, the United Nations said that credible reports had led it to estimate that up to a million Uyghurs and other Muslims were being held in "something that resembles a massive internment camp that is shrouded in secrecy". The U.N.'s International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination said that some estimates indicated that up to 2 million Uyghurs and other Muslims were held in "political camps for indoctrination", in a "no-rights zone".[191] By that time, conditions in Xinjiang had deteriorated so far that they were described by informed political scientists as "Orwellian"[165] and observers drew comparisons with Nazi concentration camps.[192] In response to the UN panel's finding of indefinite detention without due process, the Chinese government delegation officially conceded that it was engaging in widespread "resettlement and re-education" and state media described the controls in Xinjiang as "intense", but not permanent.[193]

On 31 August 2018, the United Nations committee called on the Chinese government to "end the practice of detention without lawful charge, trial and conviction", to release the detained persons, to provide specifics as to the number of interred individuals and the reasons for their detention and to investigate the allegations of "racial, ethnic and ethno-religious profiling". A BBC report quoted an unnamed Chinese official as saying that "Uighurs enjoyed full rights", pointing out that "those deceived by religious extremism ... shall be assisted by resettlement and re-education".[194]

In October 2018, BBC News published an investigative exposé claiming based on satellite imagery and testimony that hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs and other Muslim minorities are being held without trial in internment camps in Xinjiang.[177] On the other hand, the United States Department of Defense believes that around 1 million to 3 million people have been detained and placed in the re-education camps.[195] Some sources quoted in the article say "as far as I know, the Chinese government wants to remove Uyghur identity from the world."[177][196] The New York Times suggests that China has been successful in keeping countries quiet about the camps in Xinjiang due to its diplomatic and economic power, but when countries do decide to criticize the country, they do so in groups in hopes of lessening punishments from China.[197]

On 28 April 2020, the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom issued the "International Religious Freedom Annual Report 2020" . The report states that "individuals have been sent to the camps for wearing long beards, refusing alcohol, or other behaviors authorities deem to be signs of "religious extremism." Former detainees report that they suffered torture, rape, sterilization, and other abuses. In addition, nearly half a million Muslim children have been separated from their families and placed in boarding schools. During 2019, the camps increasingly transitioned from "reeducation" to forced labor as detainees were forced to work in cotton and textile factories. Outside the camps, the government continued to deploy officials to live with Muslim families and to report on any signs of "extremist" religious behavior. Meanwhile, authorities in Xinjiang and other parts of China have destroyed or damaged thousands of mosques and removed Arabic-language signs from Muslim businesses."[198]

On 17 June 2020, President Donald Trump signed the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act,[199] which authorizes the imposition of U.S. sanctions against Chinese government officials responsible for re-education camps.[200]

People

Ethnic groups

Muslims live in every region in China.[7] The highest concentrations are found in the northwest provinces of Xinjiang, Gansu and Ningxia, with significant populations also found throughout Yunnan Province in Southwest China and Henan Province in Central China.[7] Of China's 55 officially recognized minority peoples, ten groups are predominantly Muslim. The largest groups in descending order are Hui (9.8 million in year 2000 census or 48% of the officially tabulated number of Muslims), Uyghur (8.4 million, 41%), Kazakh (1.25 million, 6.1%), Dongxiang (514,000, 2.5%), Kyrgyz (144,000), Uzbeks (125,000), Salar (105,000), Tajik (41,000), Bonan (17,000) and Tatar (5,000).[7] However, individual members of traditionally Muslim groups may profess other religions or none at all. Additionally, Tibetan Muslims are officially classified along with the Tibetan people. Muslims live predominantly in the areas that border Central Asia, Tibet and Mongolia, i.e. Xinjiang, Ningxia, Gansu and Qinghai, which is known as the "Quran Belt".[201]

Genetics

The East Asian O3-M122 Y chromosome Haplogroup is found in large quantities in other Muslims close to the Hui like Dongxiang, Bo'an and Salar. The majority of Tibeto-Burmans, Han Chinese and Ningxia and Liaoning Hui share paternal Y chromosomes of East Asian origin which are unrelated to Middle Easterners and Europeans. In contrast to distant Middle Eastern and Europeans whom the Muslims of China are not related to, East Asians, Han Chinese and most of the Hui and Dongxiang of Linxia share more genes with each other. This indicates that native East Asian populations converted to Islam and were culturally assimilated to these ethnicities and that Chinese Muslim populations are mostly not descendants of foreigners as claimed by some accounts while only a small minority of them are.[202]

Number of Muslims in China

A 2009 study done by the Pew Research Center concluded there are 21,667,000 Muslims in China, accounting for 1.6% of the total population.[15] According to the CIA World Factbook, about 1–2% of the total population in China are Muslims.[203] The 2000 census counts imply that there may be up to 20 million Muslims in China. According to the textbook, "Religions in the Modern World", it states that the "numbers of followers of any one tradition are difficult to estimate and must in China as everywhere else rely on statistics compiled by the largest institutions, either those of the state – which tend to underestimate – or those of the religious institutions themselves – which tend to overestimate. If we include all the population of those designated 'national' minorities with an Islamic heritage in the territory of China, then we can conclude that there are some 20 million Muslims in the People's Republic of China.[204][205] According to SARA there are approximately 36,000 Islamic places of worship, more than 45,000 imams, and 10 Islamic schools in the country.[206] Within the next two decades from 2011, Pew projects a slowing down of the Muslim population growth in China compared to previous years, with Muslim women in China having a 1.7 fertility rate. Many Hui Muslims voluntarily limit themselves to one child in China since their Imams preach to them about the benefits of population control, while the number of children Hui in different areas are allowed to have varies between one and three children.[207] Chinese family planning policy allows minorities including Muslims to have up to two children in urban areas and three to four children in rural areas.[208]

An early historical estimate of the Muslim population of the then Qing Empire belongs to the Christian missionary Marshall Broomhall. In his book, published in 1910, he produced estimates for each province, based on the reports of missionaries working there, who had counted mosques, talked to mullahs, etc. Broomhall admits the inadequacy of the data for Xinjiang, estimating the Muslim population of Xinjiang (i.e., virtually the entire population of the province at the time) in the range from 1,000,000 (based on the total population number of 1,200,000 in the contemporary Statesman's Yearbook) to 2,400,000 (2 million "Turki", 200,000 "Hasak" and 200,000 "Tungan", as per George Hunter). He uses the estimates of 2,000,000 to 3,500,000 for Gansu (which then also included today's Ningxia and parts of Qinghai), 500,000 to 1,000,000 for Zhili (i.e., Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei), 300,000 to 1,000,000 for Yunnan and smaller numbers for other provinces, down to 1,000 in Fujian. For Mongolia (then, part of the Qing Empire) he takes an arbitrary range of 50,000 to 100,000.[209] Summing up, he arrives to the grand total of 4,727,000 to 9,821,000 Muslims throughout the Qing Empire of its last years, i.e. just over 1–2% of the entire country's estimated population of 426,045,305.[210][211][212] The 1920 edition of New International Yearbook: A Compendium of the World's Progress gave the number "between 5,000,000 and 10,000,000" as the total number of Muslims in the Republic of China.[213]

Islamic education

Hui Muslim Generals like Ma Fuxiang, Ma Hongkui, and Ma Bufang funded schools or sponsored students studying abroad. Imam Hu Songshan and Ma Linyi were involved in reforming Islamic education inside China.

Muslim Kuomintang officials in the Republic of China government supported the Chengda Teachers Academy, which helped usher in a new era of Islamic education in China, promoting nationalism and Chinese language among Muslims, and fully incorporating them into the main aspects of Chinese society.[214] The Ministry of Education provided funds to the Chinese Islamic National Salvation Federation for Chinese Muslim's education.[215][216] The President of the federation was General Bai Chongxi (Pai Chung-hsi) and the vice president was Tang Kesan (Tang Ko-san).[217] 40 Sino-Arabic primary schools were founded in Ningxia by its Governor Ma Hongkui.[218]

Imam Wang Jingzhai studied at Al-Azhar University in Egypt along with several other Chinese Muslim students, the first Chinese students in modern times to study in the Middle East.[219] Wang recalled his experience teaching at madrassas in the provinces of Henan (Yu), Hebei (Ji), and Shandong (Lu) which were outside of the traditional stronghold of Muslim education in northwest China, and where the living conditions were poorer and the students had a much tougher time than the northwestern students.[220] In 1931 China sent five students to study at Al-Azhar in Egypt, among them was Muhammad Ma Jian and they were the first Chinese to study at Al-Azhar.[221][222][223][224] Na Zhong, a descendant of Nasr al-Din (Yunnan) was another one of the students sent to Al-Azhar in 1931, along with Zhang Ziren, Ma Jian, and Lin Zhongming.[225]

Hui Muslims from the Central Plains (Zhongyuan) differed in their view of women's education than Hui Muslims from the northwestern provinces, with the Hui from the Central Plains provinces like Henan having a history of women's Mosques and religious schooling for women, while Hui women in northwestern provinces were kept in the house. However, in northwestern China reformers started bringing female education in the 1920s. In Linxia, Gansu, a secular school for Hui girls was founded by the Muslim warlord Ma Bufang, the school was named Shuada Suqin Women's Primary School after his wife Ma Suqin who was also involved in its founding.[226] Hui Muslim refugees fled to northwest China from the central plains after the Japanese invasion of China, where they continued to practice women's education and build women's mosque communities, while women's education was not adopted by the local northwestern Hui Muslims and the two different communities continued to differ in this practice.[227]

General Ma Fuxiang donated funds to promote education for Hui Muslims and help build a class of intellectuals among the Hui and promote the Hui role in developing the nation's strength.[228]

Sectarian tensions

Hui-Uyghur tension

Tensions between Hui Muslims and Uyghurs arise because Hui troops and officials often dominated the Uyghurs in the past, and crushed the Uyghurs' revolts.[229] Xinjiang's Hui population increased by over 520 percent between 1940 and 1982, an average annual growth of 4.4 percent, while the Uyghur population only grew at 1.7 percent. This dramatic increase in Hui population led inevitably to significant tensions between the Hui and Uyghur populations. Many Hui Muslim civilians were killed by Uyghur rebellion troops in 1933 known as the Kizil massacre.[230] During the 2009 rioting in Xinjiang that killed around 200 people, "Kill the Han, kill the Hui." is a common cry spread across social media among Uyghur extremists.[231] Some Uyghurs in Kashgar remember that the Hui army at the Battle of Kashgar (1934) massacred 2,000 to 8,000 Uyghurs, which causes tension as more Hui moved into Kashgar from other parts of China.[232] Some Hui criticize Uyghur separatism and generally do not want to get involved in conflict in other countries.[233] Hui and Uyghur live separately, attending different mosques.[234]

The Uyghur militant organization East Turkestan Islamic Movement's magazine Islamic Turkistan has accused the Chinese "Muslim Brotherhood" (the Yihewani) of being responsible for the moderation of Hui Muslims and the lack of Hui joining jihadist groups in addition to blaming other things for the lack of Hui Jihadists, such as the fact that for more than 300 years Hui and Uyghurs have been enemies of each other, no separatist Islamist organizations among the Hui, the fact that the Hui view China as their home, and the fact that the "infidel Chinese" language is the language of the Hui.[235][236]

Hui Muslim drug dealers are accused by Uyghur Muslims of pushing heroin on Uyghurs.[237] Heroin has been vended by Hui dealers.[238] There is a typecast image in the public eye of heroin being the province of Hui dealers.[239]

Hui sects

There have been many occurrences of violent sectarian fighting between different Hui sects. Sectarian fighting between Hui sects led to the Jahriyya rebellion in the 1780s and the 1895 revolt. After a hiatus after the People's Republic of China came to power, sectarian in fighting resumed in the 1990s in Ningxia between different sects. Several sects refuse to intermarry with each other. One Sufi sect circulated an anti-Salafi pamphlet in Arabic. Salafi movement, which is increasing in China due to fund from Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, both are major backers of Salafism, had facilitated a number of Chinese Salafi mosques.

Tibetan Muslims

In Tibet, the majority of Muslims are Hui people. Hatred between Tibetans and Muslims stems from events during the Muslim warlord Ma Bufang's rule in Qinghai such as Ngolok rebellions (1917–49) and the Sino-Tibetan War, but in 1949 the Communists put an end to the violence between Tibetans and Muslims, however, new Tibetan-Muslim violence broke out after China engaged in liberalization. Riots broke out between Muslims and Tibetans over incidents such as bones in soups and prices of balloons and Tibetans accused Muslims of being cannibals who cooked humans in their soup and of contaminating food with urine. Tibetans attacked Muslim restaurants. Fires set by Tibetans which burned the apartments and shops of Muslims resulted in Muslim families being killed and wounded in the 2008 mid-March riots. Due to Tibetan violence against Muslims, the traditional Islamic white caps have not been worn by many Muslims. Scarfs were removed and replaced with hairnets by Muslim women in order to hide. Muslims prayed in secret at home when in August 2008 the Tibetans burned the Mosque. The repression of Tibetan separatism by the Chinese government is supported by Hui Muslims.[180] In addition, Chinese-speaking Hui have problems with Tibetan Hui (the Tibetan-speaking Kache minority of Muslims).[182]

The main Mosque in Lhasa was burned down by Tibetans and Chinese Hui Muslims were violently assaulted by Tibetan rioters in the 2008 Tibetan unrest.[240] Tibetan exiles and foreign scholars alike ignore this and do not talk about sectarian violence between Tibetan Buddhists and Muslims.[181] The majority of Tibetans viewed the wars against Iraq and Afghanistan after 9/11 positively and it had the effect of galvanizing anti-Muslim attitudes among Tibetans and resulted in an anti-Muslim boycott against Muslim owned businesses.[181]: 17 Tibetan Buddhists propagate a false libel that Muslims cremate their Imams and use the ashes to convert Tibetans to Islam by making Tibetans inhale the ashes, even though the Tibetans seem to be aware that Muslims practice burial and not cremation since they frequently clash against proposed Muslim cemeteries in their area.[181]: 19

Religious practices

Islamic education in China

In the two decades up to 2006, a wide range of Islamic educational opportunities were developed to meet the needs of China's Muslim population. In addition to mosque schools, government Islamic colleges and independent Islamic colleges, more students went overseas to continue their studies at international Islamic universities in Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Iran, Pakistan and Malaysia.[7] Qīngzhēn (清真) is the Chinese term for certain Islamic institutions. Its literal meaning is "pure truth."

Muslim groups

The vast majority of China's Muslims are Sunni Muslims. A notable feature of some Muslim communities in China is the presence of female imams.[241][242] Islamic scholar Ma Tong recorded that the 6,781,500 Hui in China predominately followed the Orthodox form of Islam (58.2% were Gedimu, a non-Sufi mainstream tradition that opposed unorthodoxy and religious innovation), mainly adhering to the Hanafi Maturidi Madhhab.[243][244] However a large minority of Hui are members of Sufi groups. According to Tong, 21% Yihewani, 10.9% Jahriyya, 7.2% Khuffiya, 1.4% Qadariyya and 0.7% Kubrawiyya.[245] Shia Chinese Muslims are mostly Ismailis, including Tajiks of the Tashkurgan and Sarikul areas of Xinjiang.

Chinese Muslims and the Hajj

It is known that Admiral Zheng He (1371–1435) and his Muslim crews had made the journey to Mecca and performed the Hajj during one of the former's voyages to the western ocean between 1401–1433.[246] Other Chinese Muslims may have made the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in the following centuries; however, there is little information on this. General Ma Lin made a Hajj to Mecca.[247] General Ma Fuxiang along with Ma Linyi sponsored Imam Wang Jingzhai when he went on hajj to Mecca in 1921.[248] Yihewani Imam Hu Songshan went on Hajj in 1925.[249]

Briefly during the Cultural Revolution, Chinese Muslims were not allowed to attend the Hajj and only did so through Pakistan, but this policy was reversed in 1979. Chinese Muslims now attend the Hajj in large numbers, typically in organized groups of roughly 10,000 each year,[250] with a record 10,700 Chinese Muslim pilgrims from all over the country making the Hajj in 2007.[251] Over 11,000 from Xinjiang reportedly went to the Hajj in 2019.[252]

Representative bodies

Islamic Association of China

Established by the government, the Islamic Association of China claims to represent Chinese Muslims nationwide. At its inaugural meeting on May 11, 1953, in Beijing, representatives from 10 nationalities of the People's Republic of China were in attendance. The association was to be run by 16 Islamic religious leaders charged with making "a correct and authoritative interpretation" of Islamic creed and canon. Its brief is to compile and spread inspirational speeches and help imams "improve" themselves, and vet sermons made by clerics around the country.

Some examples of the religious concessions granted to Muslims are:

- Muslim communities are allowed separate cemeteries

- Muslim couples may have their marriage consecrated by an Imam

- Muslim workers are permitted holidays during major religious festivals

- Chinese Muslims are also allowed to make the Hajj to Mecca, and more than 45,000 Chinese Muslims have done so in recent years.[253]

Culture and heritage

Although contacts and previous conquests have occurred before, the Mongol conquest of the greater part of Eurasia in the 13th century permanently brought the extensive cultural traditions of China, central Asia and western Asia into a single empire, albeit one of separate khanates, for the first time in history. The intimate interaction that resulted is evident in the legacy of both traditions. In China, Islam influenced technology, sciences, philosophy and the arts. For example, the Chinese adopted much Islamic medical knowledge such as wound healing and urinalysis. However, the Chinese were not the only ones to benefit from the cultural exchanges of the Silk Road. Islam showed many influences from buddhist China in their new techniques in art, especially when humans began to be depicted in paintings which was thought to be forbidden in Islam.[254] In terms of material culture, one finds decorative motifs from central Asian Islamic architecture and calligraphy and the marked halal impact on northern Chinese cuisine.

Taking the Mongol Eurasian empire as a point of departure, the ethnogenesis of the Hui, or Sinophone Muslims, can also be charted through the emergence of distinctly Chinese Muslim traditions in architecture, food, epigraphy and Islamic written culture. This multifaceted cultural heritage continues to the present day.[255]

Military

Muslims have often filled military positions, and many Muslims have joined the Chinese army.[256] Muslims served extensively in the Chinese military, as both officials and soldiers. It was said that the Muslim Dongxiang and Salar were given to "eating rations", a reference to military service.[257]

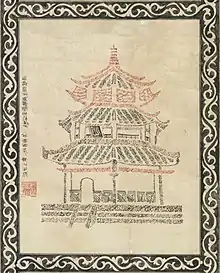

Islamic architecture in China

.jpg.webp)

In Chinese, a mosque is called qīngzhēn sì (清真寺) or "pure truth temple." The Huaisheng Mosque and Great Mosque of Xi'an (first established during the Tang era) and the Great Southern Mosque in Jinan, whose current buildings date from the Ming Dynasty, do not replicate many of the features often associated with traditional mosques. Instead, they follow traditional Chinese architecture. Mosques in western China incorporate more of the elements seen in mosques in other parts of the world. Western Chinese mosques were more likely to incorporate minarets and domes while eastern Chinese mosques were more likely to look like pagodas.[258] An important feature in Chinese architecture is its emphasis on symmetry, which connotes a sense of grandeur; this applies to everything from palaces to mosques. One notable exception is in the design of gardens, which tends to be as asymmetrical as possible. Like Chinese scroll paintings, the principle underlying the garden's composition is to create enduring flow; to let the patron wander and enjoy the garden without prescription, as in nature herself.

On the foothills of Mount Lingshan are the tombs of two of the four companions that Muhammad sent eastwards to preach Islam. Known as the "Holy Tombs," they house the companions Sa-Ke-Zu and Wu-Ko-Shun—their Chinese names, of course. The other two companions went to Guangzhou and Yangzhou.[31]

Chinese buildings may be built with bricks, but wooden structures are the most common; these are more capable of withstanding earthquakes, but are vulnerable to fire. The roof of a typical Chinese building is curved; there are strict classifications of gable types, comparable with the classical orders of European columns. As in all regions the Chinese Islamic architecture reflects the local architecture in its style. China is renowned for its beautiful mosques, which resemble temples. However, in western China the mosques resemble those of the middle east, with tall, slender minarets, curvy arches and dome shaped roofs. In northwest China where the Chinese Hui have built their mosques, there is a combination of east and west. The mosques have flared Chinese-style roofs set in walled courtyards entered through archways with miniature domes and minarets.[258] The first mosque was the Great Mosque of Xian or the Xian Mosque, which was created in the Tang Dynasty in the 7th century.[259]

Ningxia officials notified on 3 August 2018 that the Weizhou Grand Mosque will be forcibly demolished on Friday because it had not received the proper permits before construction.[260][261][262] Officials in the town were saying the mosque had not been given proper building permits, because it is built in a Middle Eastern style and include numerous domes and minarets.[260][261] The residents of Weizhou were alarmed each other by social media and finally stopped the mosque destruction by public demonstrations.[261] According to a 2020 report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, since 2017, Chinese authorities have destroyed or damaged 16,000 mosques in Xinjiang – 65% of the region's total.[263][264]

Halal food in China

Halal food has a long history in China. The arrival of Arabian and Persian merchants during the Tang and Song dynasties saw the introduction of the Muslim diet. Chinese Muslim cuisine adheres strictly to the Islamic dietary rules with mutton and lamb being the predominant ingredient. The advantage of Muslim cuisine in China is that it has inherited the diverse cooking methods of Chinese cuisine for example, braising, roasting, steaming, stewing and many more. Due to China's multicultural background Muslim cuisine retains its own style and characteristics according to regions.[265] Restaurants serving such cuisine are frequented by both Muslim and Han Chinese customers.[266]

Due to the large Muslim population in Western China, many Chinese restaurants cater to Muslims or the general public but are run by Muslims. In most major cities in China, there are small Islamic restaurants or food stalls typically run by migrants from Western China (e.g., Uyghurs), which offer inexpensive noodle soup. Lamb and mutton dishes are more commonly available than in other Chinese restaurants, due to the greater prevalence of these meats in the cuisine of western Chinese regions. Commercially prepared food can be certified Halal by approved agencies.[267] In Chinese, halal is called qīngzhēncài (清真菜) or "pure truth food." Beef and lamb slaughtered according to Islamic rituals is also commonly available in public markets, especially in North China. Such meat is sold by Muslim butchers, who operate independent stalls next to non-Muslim butchers.

In October 2018, the government launched an official anti-halal policy, urging officials to suppress the "pan-halal tendency", seen as an encroachment by religion into secular life and a source of religious extremism.[268]

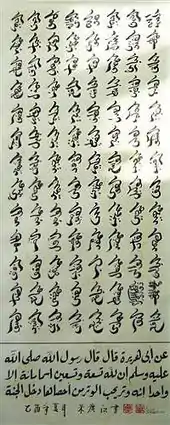

Sini

Sini is a Chinese Islamic calligraphic form for the Arabic script. It can refer to any type of Chinese Islamic calligraphy, but is commonly used to refer to one with thick and tapered effects, much like Chinese calligraphy. It is used extensively in mosques in Eastern China and to a lesser extent in Gansu, Ningxia and Shaanxi. A famous Sini calligrapher is Hajji Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang.

Xiao'erjing

Xiao'erjing (also Xiao'erjin or Xiaojing) is the practice of writing Sinitic languages such as Mandarin (especially the Lanyin, Zhongyuan and Northeastern dialects) or the Dungan language in the Arabic script. It is used on occasion by many ethnic minorities who adhere to the Islamic faith in China (mostly the Hui, but also the Dongxiang and the Salar) and formerly by their Dungan descendants in Central Asia.

Martial arts

There is a long history of Muslim development and participation at the highest level of Chinese wushu. The Hui started and adapted many of the styles of wushu such as bajiquan, piguazhang and liuhequan. There were specific areas that were known to be centers of Muslim wushu, such as Cang County in Hebei Province. These traditional Hui martial arts were very distinct from the Turkic styles practiced in Xinjiang.[269]

Literature

The Han Kitab was a collection of Chinese Islamic texts written by Chinese Muslim which synthesized Islam and Confucianism. It was written in the early 18th century during the Qing dynasty. Han is Chinese for Chinese and kitab (ketabu in Chinese) is Arabic for book.[270] Liu Zhi wrote his Han Kitab in Nanjing in the early 18th century. The works of Wu Sunqie, Zhang Zhong and Wang Daiyu were also included in the Han Kitab.[271]

The Han Kitab was widely read and approved of by later Chinese Muslims such as Ma Qixi, Ma Fuxiang and Hu Songshan. They believed that Islam could be understood through Confucianism.

Education

A lot of Chinese students including male and females join International Islamic University, Islamabad to gain Islamic knowledge. For some Muslim groups in China, such as the Hui and Salar minorities, coeducation is frowned upon; for some groups such as Uyghurs, it is not.[272]

Women imams

With the exception of China, the world has very few mosques directed by women.[273] Among the Hui, women are allowed to become imams or ahong, and a number of woman-only mosques have been established. The tradition evolved from earlier Quranic schools for girls, with the oldest, the Wangjia Hutong Women's Mosque in Kaifeng, dating to 1820.[274]

Famous Muslims in China

Explorers

- Zheng He, mariner and explorer.

- Fei Xin, Zheng He's translator.

- Ma Huan, a companion of Zheng He.

- Generals from the Qing era:

- Dong Fuxiang

- Ma Julung

- Ma Xinyi (late Qing dynasty)

- Generals in the Republic of China:

- Ma Zhancang

- Ma Fuyuan

- Ma Ju-lung

- Ma Zhanhai

- Bai Chongxi

- Ma Ching-chiang (Lt. General)

- Warlords of the Ma clique during the Republic of China era:

- Ma Bufang

- Ma Chung-ying

- Ma Fuxiang

- Ma Hongkui

- Ma Dunjing (1910-2003)

- Ma Hongbin

- Ma Dunjing (1906-1972)

- Ma Lin

- Ma Qi

- Ma Hu-shan

- Ma Zhan'ao

- Ma Qianling

- Ma Fushou

- Ma Fulu

- Ma Anliang

- Ma Guoliang

- Ma Buqing

- Ma Bukang

- Ma Jiyuan

- Ma Chengxiang

- Ma Haiyan

- Generals from the 36th Division (National Revolutionary Army):

- Ma Sheng-kuei

- Su Chin-shou

- Pai Tzu-li

- Du Wenxiu, Ma Hualong and Ma Zhan'ao, leaders of the Panthay Rebellion in Yunnan and the Muslim rebellion in northwestern China.

- Ma Shenglin, great-uncle of Ma Shaowu and rebel during the Panthay Rebellion.

- Ma Zhanshan, guerilla during the Second Sino-Japanese War.

- Zuo Baogui (1837–1894), Qing Muslim general from Shandong who died while defending Pingyang, Korea, from the Japanese.[275]

Religious

- Liu Zhi (c. 1660 – c. 1739), Islamic author (Qing dynasty).

- Qi Jingyi (1656–1719), Sufi master who introduced the Qadiriyyah school to China.

- Ma Laichi (1681?–1766?), Sufi master who brought the Khufiyya Naqshbandi movement to China.

- Ma Mingxin (1719–1781), founder of the Jahriyya Naqshbandi movement.

- Ma Wanfu, founder of the Yihewani.

- Ma Qixi (1857–1914), founder of the Xidaotang.

- Ma Yuanzhang, Jahriyya Sufi leader.

- Wang Jingzhai, one of the four famous Imams of the Republican period

- Hu Songshan (1880–1956), Yihewani reformer and Chinese nationalist.

Scholars and writers

- Bai Shouyi, historian.

- Tohti Tunyaz, historian.

- Ma Zhu, Islamic scholar and Southern Ming loyalist.

- Yusuf Ma Dexin, first translator of the Qur'an into Chinese.

- Muhammad Ma Jian, author of the most popular Chinese translation of the Qur'an.

- Wang Daiyu, Master Supervisor of the Imperial Observatory (Ming dynasty).[276]

- Zhang Chengzhi, contemporary author.

- Pai Hsien-yung, contemporary author, son of Bai Chongxi.

- Yusuf Liu Baojun, Contemporary Author and Historian.

Officials

- Ma Xinyi, (馬新貽), official and a military general of the late Qing dynasty in China.

- Ma Linyi Gansu Minister of Education

- Tang Kesan, representative of the Kuomintang in Xikang

Martial arts

- Ma Xianda, martial artist.

- Wang Zi-Ping, member of the Righteous and Harmonious Fists (the "Boxers") during the Boxer Rebellion.

- Chang Dongsheng, martial artist and Shuai jiao teacher.

Arts

- Noor Deen Mi Guangjiang, calligrapher.

See also

- Islam in Hong Kong

- Islam in Macau

- Islam in Taiwan

- Islamophobia in China

- Ahmadiyya in China

- The Hundred-word Eulogy

- Chinese Muslim cuisine

- Islam by country

- Religion in China

- Demographics of the People's Republic of China

- Christianity in China

- Proposed demolition of Weizhou Grand Mosque

- Islam in Bangladesh

- Islam in Indonesia

- Islam in Iran

- Islam in Nigeria

- Islam in Pakistan

- Islam in the Philippines

- Islam in Russia

Notes

References

Citations

- B. L. K. Pillsbury (1981), "Muslim History in China: A 1300-year Chronology", Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 3 (2): 10–29, doi:10.1080/02666958108715833.

- "The Terrible 'Sinicization' of Islam in China". 15 January 2021.

- "The World Factbook". cia.gov. Retrieved 2007-05-30.

- "The Muslim Minority Nationalities of China: Toward Separatism or Assimilation?". Princeton University.

- August 12, Hannah Beech; Edt, 2014 5:30 Am. "If China Is Anti-Islam, Why Are These Chinese Muslims Enjoying a Faith Revival?". Time. Retrieved 2021-05-07.